Figures & data

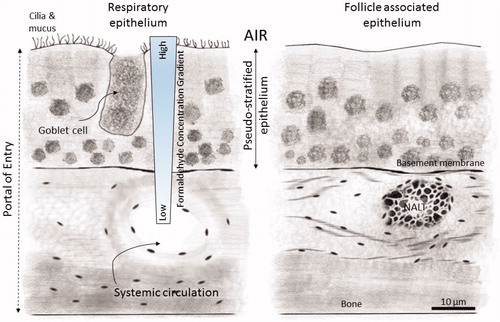

Figure 1. Representation of the reaction of inhaled formaldehyde in mammalian nasal epithelium which rapidly reacts with macromolecules in the tissue and the albumin in the mucus that lines the respiratory epithelium resulting in a steep concentration gradient. After crossing the basement membrane, formaldehyde can react further with macromolecules in the submucosal layer or reach the systemic circulation. The nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) that is generally present near the ethmoid turbinates on either side of the nasal septum and near the ventral nasopharyngeal duct is one putative site of formaldehyde interactions with lymphoid tissues, but direct evidence that supports this hypothesis is lacking. (Figure reproduced from National Research Council (Citation2011)).

Table 1. Problem formulation review questions.

Table 2. Literature search strings*.

Table 3. Definitions of confidence levels and corresponding scores for individual study components.

Table 4. Definition of overall study quality levels and corresponding study quality scores.

Table 5. SciRAP criterion for evaluating study relevance.

Table 6. Study quality and study relevance scoring results.

Table 7. List of unacceptable studies determined during study quality evaluation.

Table 8. Overview of postulated MOAs.

Table 9. Summary of available studies associated with key events 2 and 3 of the postulated MOAs.

Table 10. Integration of evidence for postulated MOA 1 – initiation of leukemia by direct damage to hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow.

Table 11. Formaldehyde-specific dose-response and temporal concordance data for leukemia.

Table 12. Integration of Evidence for Each of the Key Events Associated with the Postulated MOAs.

Table 13. Comparative weight of evidence for postulated MOA 2 – toxicity to circulating blood stem cells and progenitors.

Table 14. Results from studies measuring endogenous and exogenous DNA-adducts and DNA–protein crosslinks in multiple species.

Table 15. Comparative weight of evidence for postulated MOA 3 and 4 – targeting pluripotent nasal cells or HSCs/HSPs in lung tissue.

Table 16. Comparison of formaldehyde regulatory standards, exogenous formaldehyde concentrations in food and drink, and endogenous production of formaldehyde in humans.