Figures & data

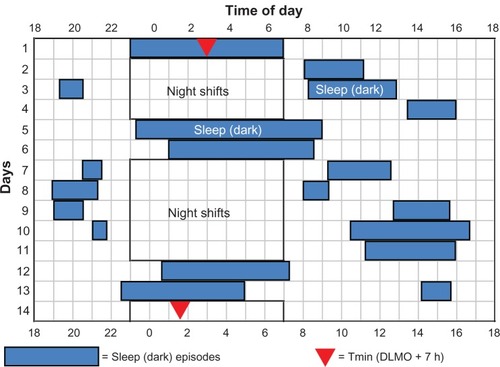

Figure 1 Sleep-and-light schedule for night-shift work that we tested to determine if it could align circadian rhythms with the sleep schedule enough to move the temperature minimum (Tmin) to within sleep.

Abbreviation: DLMO, dim-light melatonin onset.

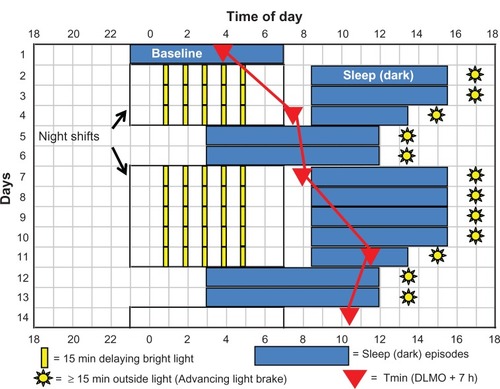

Figure 2 Sleep times (blue rectangles) and baseline and final temperature minima (Tmin, filled red triangles) for a control subject in study 4.

Abbreviation: DLMO, dim-light melatonin onset.

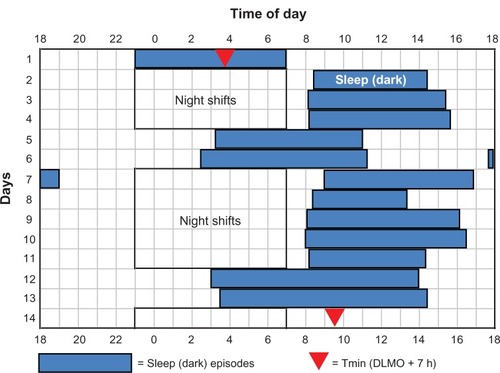

Figure 3 Sleep times for a control subject in study 4Citation243 that had short daytime sleep after night shifts, sometimes stayed awake for many hours in the morning after night work, napped before some night shifts, and went to sleep and woke up relatively early on days off.Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. Practical interventions to promote circadian adaptation to permanent night shift work: study 4. J Biol Rhythms. 2009;24:161–172, Copyright © 2009 by the Journal of Biological Rhythms. Reprinted by Permission of SAGE Publications.Citation243

Abbreviation: DLMO, dim-light melatonin onset.

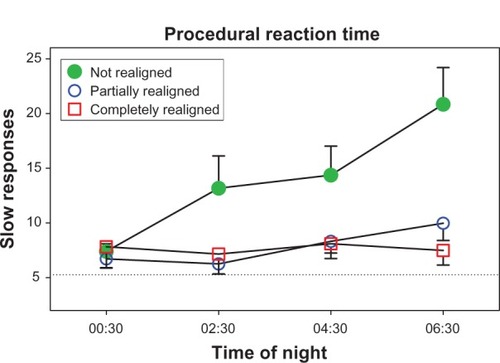

Figure 4 The number of slow responses on the procedural reaction-time task averaged over three night shifts (days 8–10 in ) for subjects whose circadian clocks were not realigned (n = 12), partially realigned (n = 21), or completely realigned (n = 6) to night work by the end of their series of night shifts and days off.

Copyright © 2009. Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. A compromise circadian phase position for permanent night work improves mood, fatigue, and performance. Sleep. 2009;32:1481–1489.Citation244

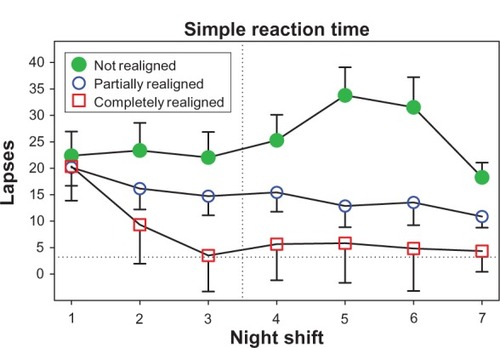

Figure 5 The number of lapses (reaction time > 500 milliseconds) at 6:30 am on the simple reaction-time task across successive night shifts for subjects whose circadian clocks were not realigned (n = 12), partially realigned (n = 21), or completely realigned (n = 6) to night work by the end of their series of night shifts and days off.

Copyright © 2009. Smith MR, Fogg LF, Eastman CI. A compromise circadian phase position for permanent night work improves mood, fatigue, and performance. Sleep. 2009;32:1481–1489.Citation244

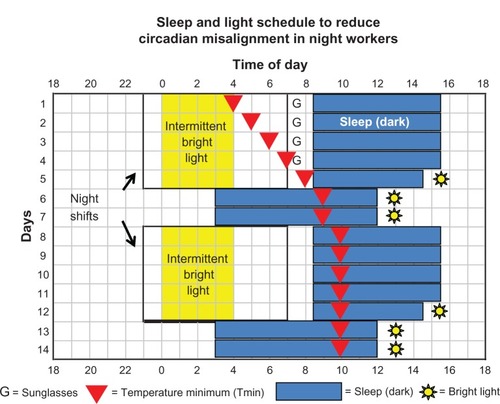

Figure 6 Sleep-and-light schedule designed to reduce the circadian misalignment produced by night-shift work, and thus to improve night-shift performance as well as sleep both after work and on days off.