Figures & data

Table 1. Primer and TaqMan probe sequences for qRT-PCR.

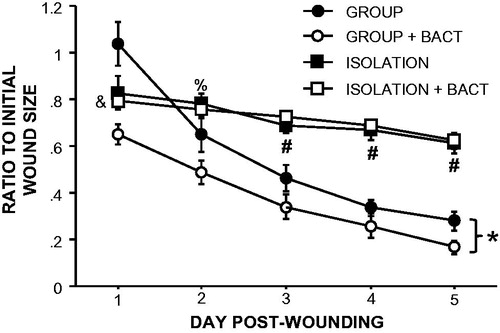

Figure 1. Effects of social isolation and chronic restraint on physiology and behavior. (A) Three weeks of social isolation (ISOLATION) increased body mass compared with group-housed controls (GROUP), whereas daily 12–13-h restraint for three days (RESTRAINT) decreased body mass relative to controls that were food- and water-deprived during the same time period (FWD). *p < 0.05 compared with all other groups; &p < 0.05 between group and isolation treatments. (B) Three days of chronic restraint (12 h/day) increased circulating corticosterone at rest (baseline), immediately after a 30-min acute restraint challenge, and 55 min after the challenge (recovery) compared with FWD controls and three weeks of social isolation or group housing. Isolation tended to decrease recovery corticosterone concentrations relative to group-housed controls. *p < 0.05 relative to all other groups, #p < 0.05 relative to all other groups except group-housed controls, p = 0.09 between ISOLATION and GROUP. (C) Four weeks of social isolation increased total distance traveled and average locomotor velocity during a 5-min open field test compared with group-housed controls. *p < 0.05. n = 10/group.

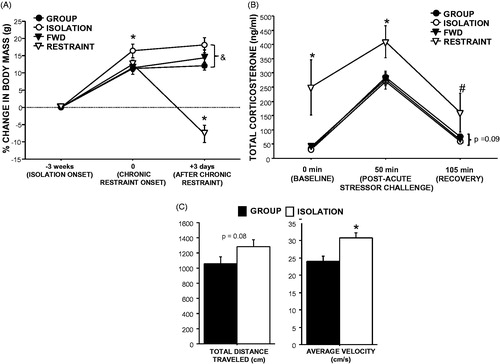

Figure 2. Social isolation and restraint comparably impair dermal wound closure. Three weeks of social isolation (open circles) reduced wound closure (relative to initial wound area) compared with group-housed controls (closed circles) on Days 3–5 post-wounding. Daily 12-h restraint (open triangles) 3 days prior and throughout wound healing decreased wound closure compared with food- and water-deprived controls (closed triangles) on Days 1–5 post-wounding. n = 15/group; #p < 0.05 for FWD versus RESTRAINT, *p < 0.001 for both stress groups versus respective controls, &p < 0.05 RESTRAINT versus ISOLATION.

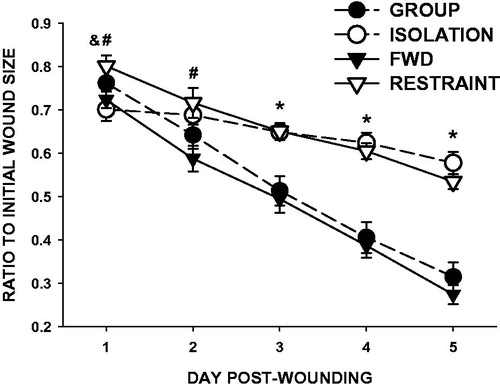

Figure 3. Social isolation reduces, and restraint increases, total bacterial load. Three weeks of social isolation (ISOLATION) decreased wound total bacterial load on Days 1, 3, and 5 post-wounding compared with group-housed controls (GROUP). Conversely, daily 12-h restraint 3 days prior and throughout wound healing (RESTRAINT) increased wound total bacterial load on Days 1, 3, and 5 post-wounding compared with food- and water-deprived controls (FWD). n = 4–5/group; *p < 0.05 compared with GROUP, #p < 0.05 compared with FWD.

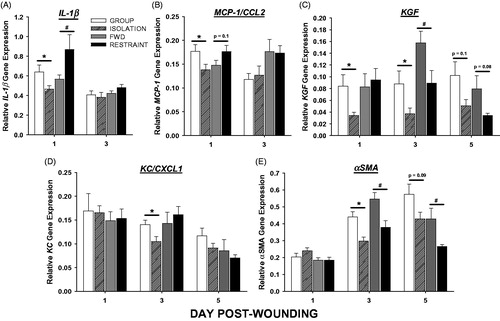

Figure 4. Social isolation alters healing gene expression differently than restraint. Three weeks of social isolation decreased wound (A) interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and (B) monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) mRNA on Day 1, decreased (C) keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) mRNA on Days 1 and 3, and decreased (D) keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC) and (E) α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) mRNA on Day 3 post-wounding as measured by qRT-PCR. Daily 12-h restraint 3 days prior and throughout wound healing increased IL-1β on Day 1, decreased KGF and KC on Day 3, and decreased αSMA on Days 3 and 5 post-wounding. n = 9–12/group; *p < 0.05 compared with GROUP, #p < 0.05 compared with FWD.

Table 2. Effects of social isolation and restraint stress on wound gene expression for factors that regulate healing.

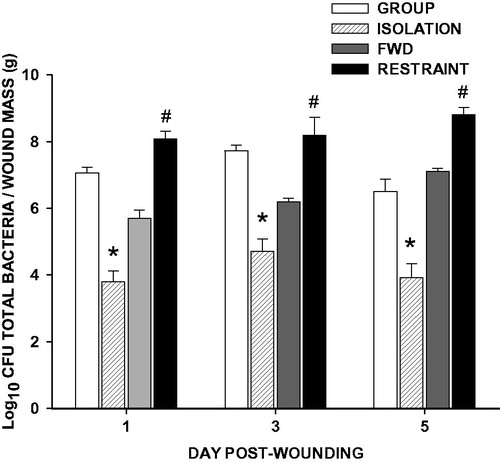

Figure 5. Supplementation of bacteria on wounds does not improve healing in socially isolated mice. Supplementation with indigenous bacteria to wounds at the time of wounding improved healing in group-housed but not isolated mice. n = 5–10/group; *p < 0.05 repeated measures between GROUP and GROUP + BACT; #p < 0.05 between GROUP, GROUP + BACT and ISOLATION, ISOLATION + BACT; &p < 0.05 between ISOLATION + BACT and both GROUP and GROUP + BACT; %p < 0.05 between ISOLATION + BACT and GROUP + BACT.