Abstract

Objective: To investigate the relationship between subjective symptoms of orofacial pain and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), as well as psychological distress in population-based middle-aged women.

Material and methods: The two study samples comprised 1059 women, 38 and 50 years old, in representative cross-sectional studies. Women with long-lasting, frequent pain or headaches, related to temporomandibular disorders (TMD), with moderate-to-high estimates were analysed in relation to the non-case group. OHRQoL was measured using the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-5). Psychological distress was measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Sense of Coherence (SOC-13).

Results: Women with orofacial pain (n = 82, 7.7%) had a significantly higher mean score on the OHIP-5, HADS-A and HADS-D and a lower mean score for SOC-13. In a multivariable logistic regression, orofacial pain was statistically significantly associated with poorer OHRQoL (OR = 1.2) and signs of depression (HADS-D) (OR = 2.0). A higher score for SOC-13 protected from the experience of orofacial pain (OR = 0.95).

Conclusion: Orofacial pain was associated with poorer OHRQoL and signs of psychological distress. In interpreting the value of SOC, women with orofacial pain also appear to have a poorer adaptive capacity.

Introduction

Orofacial pain is pain localized in the oral and facial regions. The most prevalent reasons for such pain are tooth-related diagnoses and the ‘umbrella term; temporomandibular disorders (TMD) [Citation1]. TMD also include functional alterations in the masticatory system [Citation1–3]. The prevalence of TMD is dependent on the included diagnostic criteria, but its estimated occurrence is approximately 10% of the adult population [Citation4].

Headache is an almost universal painful condition; few people are spared during their lifetime [Citation5]. The classification from the International Headache Society (IHS) [Citation6] involves primary and secondary headache disorders. Primary headaches are common in persons with TMD symptoms and TMD symptoms are common in persons with headache [Citation7,Citation8]. Epidemiologic studies have shown that pain from TMD and headache is more common in women than in men [Citation3]. The prevalence of reports of pain commonly decreases in older age groups, compared to younger age groups [Citation4,Citation7].

Individuals with chronic, long-lasting pain, especially wide spread pain, often show high levels of concerns about somatic symptoms and more psychological distress [Citation9]. Common mental conditions, such as anxiety and depression, may affect an individual’s vulnerability and coping strategies in relation to various types of disease, including pain conditions such as TMD and headache [Citation9–14]. Pain frequency, rather than specific diagnosis also appears to be associated with psychological distress [Citation13]. Factors that can protect from the development of long-lasting pain are self-efficacy and ‘positive mood’, which in turn influence both risk factors [Citation12] and treatment modalities [Citation15,Citation16].

Quality of life (QoL) is a complex, broad-ranged concept of the individuals’ perception of their position in life with regard to the surrounding society. Health-related quality of life is evaluated with psychometric instruments in relation to different health conditions and is a common outcome variable in research. In large-scale epidemiological surveys, short versions may be preferred. The choice of questionnaire may be difficult since both global and specific assessments such as oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) are available [Citation17]. The relation between TMD-pain and OHRQoL is established, persons with pain often have poorer OHRQoL. There are also correlations between TMD-pain, OHRQoL and psychological distress [Citation13,Citation17].

Women appear to be the core subjects with painful TMD and headache and the important role of psychological factors and impact on quality of life is underlined in several studies. Many of these studies are based on selected clinical, care-seeking samples rather than on population-based cohorts [Citation4,Citation11]. Care-seeking individuals with pain could have a different psychological profile from that of individuals with pain in the general population. Data from population-based studies of these issues are therefore of interest for external validity [Citation18], why it is of importance to perform such studies to reveal knowledge from the general population. For the past few decades, an ongoing epidemiologic study of health in the female population in Gothenburg, Sweden, has been collecting data on these issues.

The aim was to investigate the relationship between subjective symptoms of TMD-related pain and headache and oral health-related quality of life, as well as psychological distress, in a population-based group of middle-aged women. The null hypothesis was that there is no difference in OHRQoL and psychological distress with respect to chronic pain.

Material and methods

The study population consisted of data provided of 1073 middle-aged women participating in the ongoing prospective Population Study of Women in Gothenburg (PSWG). This is a medical and dental systematic study of women that, since 1968, has been conducted every 12 years by the University of Gothenburg. The participants have been shown to be representative of the middle-aged female population in the region [Citation19,Citation20]. The PSWG has focused on middle-aged and elderly women´s health [Citation19–21]. Every examination, which has been both medical and dental, included somatic as well as psychiatric assessments. Middle-aged women, cohorts with 38- and 50-year old, have been invited using the same inclusion criteria in all examinations from 1968 (1980, 1992, 2004 and 2016) to ensure representativeness. A systematic random sampling method was used and women born on day 6, 12, 18 and 24 of the month, living in the Gothenburg area, collected from the Swedish Population Register, were invited. The only exclusion criterion was an inability to read and understand Swedish.

This cross-sectional study included the 38- and 50-year old women examined in 2004 (born in 1954 and 1966) and 2016 (born in 1978 and 1966). The procedures were the same in 2004 and in 2016.

Measurements

Information about marital status (living alone or with a partner) and educational level was obtained. The latter was based on years of school attendance and reported as; low (1–9 years), medium (10–12 years) and high level (≥13 years).

Based on Locker’s articles [Citation22], an assessment of subjective pain in the jaws and/or head during the last month was performed as part of the dental examination´s questionnaires. The formulation of the five questions is shown in . There were three questions related to TMD pain, and a fourth question related to headaches. The fifth question was additional and evaluated symptoms of TMD. In all four pain questions, the women also stated for how long they had noticed the pain (less than a week/one week to one month/one to six months/over six months), the level of intensity (rated on a 0-100 numeric rating scale (NRS) with 100 as the maximum), and the frequency (never/once a month/once a week/many times a week/daily). These pain characteristics were considered in the subsequent analysis. Long-lasting severe pain was defined as; chronic (lasted more than one month), intensive (more than 39 NRS) and frequent (more than once a week) in any of the four pain questions.

Table 1. Formulation of the questions in the questionnaire.

Severe orofacial pain group, was constructed, with the aim of including long-lasting intensive and frequent pain in the face and head. Women with one or more positive answers to the first three TMD-related questions and meeting the above severity criteria of chronicity, intensity and frequency were included. The participants with positive answer to the fourth question about headaches, meeting the above criteria, were included in the severe orofacial pain group if any TMD-related symptoms, regardless of severity, existed at the same time.

The severe orofacial pain group therefore comprised women with severe TMD-pain, plus the women with severe headache with concomitant TMD symptoms. In the analysis, the severe orofacial pain group was analysed in relation to the non-case group.

Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) was assessed using the Oral Health Impact Profile, OHIP-5 [Citation17,Citation23,Citation24]. The OHIP-5, comprises five questions concerning functional limitation, pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, and handicap. Each item in OHIP-5 has five choices on an ordinal rating scale; 0 (never) up to 4 (very often), for a sum of score between 0 and 20. Higher values indicate poorer OHRQoL. The mean score was calculated and the OHIP-5 was also dichotomized into good OHRQoL (scoring 3 or 4 on no more than one item) vs poor OHRQoL (scoring 3 or 4 on at least two items) [Citation24].

Anxiety and depression were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), originally developed in 1983 [Citation25] to screen clinically significant anxiety and depression in medical non-psychiatric patients. The HADS focuses on cognitive and emotional aspects of general anxiety and depression. It comprises seven questions on anxiety and seven questions on depression, each with four choices, giving scores from 0–3, maximum 21, on HADS-A and on HADS-D, respectively. Anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) are scored separately and higher scores indicate a higher degree of distress. To indicate psychological distress, a commonly used cut-off score, score ≥8, was used [Citation26], as well as mean scores.

Sense of Coherence (SOC) [Citation27] relates to the adaptive capacity of humans and is the main constituent of the ‘salutogenic’ theory, which is a social health-related theory, to explore the correlations between health, stress, and coping. It evaluates the individual’s capability to use existing resources in order to overcome difficulties and cope with life stressors to perform healthy behaviour and stay well. The version used here was the SOC-13 [Citation28]. Each item was scored on a scale from 1–7 points, giving a total range of 13 to 91 points for the SOC score. A higher score indicates a stronger sense of coherence, but no reference score has been reported in the literature.

Ethics

The regional ethical review board in Gothenburg approved the study (Dnr 453-04, 564-03, 258-16). All participants gave their written informed consent.

Statistics

Analyses were conducted with SPSS version 24 (Armonk, New York). Mean values, standard deviation, median and tests for normality were determined for the instruments (skewness, kurtosis and Kolmogorov–Smirnov). Due to the large sample size, these tests for normality all showed significant results indicating slight violations of the assumption of normality. Thus, normality was checked by inspecting histograms, means, medians, and standard deviations. Based on these results the t-test was applied on the continuous variables since the test is robust for violations of normality when having large sample sizes. The chi-square test was used for categorical data. A significance level of p < .05 was used. A Bonferroni correction, using alpha less than 0.0036, was applied in order to reduce the risk for type-I error while analysing multiple comparisons. The effect size according to Cohens d was calculated for the differences between groups on the instruments.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed using an enter procedure with the dependent variable severe orofacial pain and the independent variables HADS-A, HADS-D, SOC-13, OHIP-5, age, examination year, marital status, and education. Collinearity of the included variables was checked using Spearman correlation and cross-tabulation. The associations are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

A total of 1059 (98.7%) of the 1073 participating women were included in the cross-sectional analysis with consideration of completed instruments. shows the participation rates, marital status and level of education.

Table 2. The number of invited and participating women, aged 38 and 50 years, at the examinations in 2004 and 2016, together with marital status and educational level.

The distribution of the severe orofacial pain group, that is, women with severe TMD-pain, plus women with severe headache with simultaneously TMD symptoms, is shown in . Severe orofacial pain was found in 7.7% (n = 82) of all the participating women, with the largest prevalence among 50-year olds in 2016. Affirmative answers for subjective symptoms of pain did not differ significantly between the four cohorts in the severe orofacial pain group. The analysis was therefore performed with the merged severe orofacial pain group in relation to the remaining non-case group. Most of the women in the severe orofacial pain group had experienced the pain for more than six months (77%), while the others had experienced it for one to six months. The mean value for pain on the NRS was 60. One-third reported daily pain, while two-thirds reported pain many times a week. Symptoms of any TMD (, questions 1, 2, 3, 5) was found in 311 women, while any headache ( question 4) was reported by 557 women.

Table 3. The distribution of subjective symptoms of TMD-related pain and headache in four cohorts of middle-aged women.

The mean scores from the Swedish versions of the HADS, SOC-13 and OHIP-5 in the severe orofacial pain group, as well as the non-case and total groups, are given in , including the effect sizes. The women with severe orofacial pain had a statistically significant higher mean value for HADS-A, HADS-D, and the OHIP-5, and a significantly lower mean value for the SOC-13 than in the non-case group.

Table 4. The distribution of mean scores for anxiety and depression from the HADS, SOC-13 and OHIP-5 in the total, non-case and severe orofacial pain group.

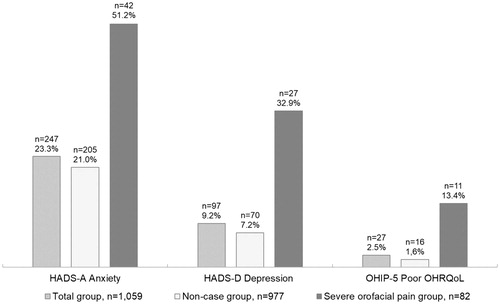

Women with signs of anxiety (HADS-A score ≥8) and signs of depression (HADS-D score ≥8) were significantly more common in the severe orofacial pain group compared with the non-case group (p < .001), see the . The proportion of poor OHRQoL, that is, the dichotomized level of the OHIP-5, was 1.6% in the non-case group, differing significantly from that in the severe orofacial pain group, 13%, (p < .001). A score of 3 or 4 for the questions in the OHIP-5 was significantly more common in the severe orofacial pain group than in the non-case group (data not shown).

Figure 1. Proportions of signs of anxiety (HADS-A, score ≥8), signs of depression (HADS-D, score ≥8) and poor OHRQoL (score three or four on more than two items in the OHIP-5) in a group of 1059 middle-aged Swedish women.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis of the relationship between the psychological variables and severe orofacial pain was performed (). All the available independent variables were determined not to be correlating hazardously with each other, based on the correlation analysis (Spearman’s ρ ≤ 0.60) or when cross-tabulated, variable by variable. Highest value between anxiety and SOC (0.52), anxiety-depression (0.40), depression-SOC (0.41). The others were lower, between 0.01 and 0.24. The model in explained 19.7% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in severe orofacial pain and correctly classified 92.0% of cases. OHIP-5, measured on the continuous scale, revealed a significant association with severe orofacial pain, with an OR of 1.2. Women with signs of depression (HADS-D ≥ 8) were two times more likely than women without signs of depression to exhibit severe orofacial pain. Thus, a lower OHIP-5 score and HAD-D score, and a higher SOC-13 score protected against the likelihood of exhibiting severe orofacial pain. Anxiety (HADS-A ≥ 8), level of education, marital status, age and examination year were not significant when it came to explaining severe orofacial pain.

Table 5. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors related to the dependent variable severe orofacial pain in a cross-sectional female representative cohort.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore the association between TMD-related pain in the jaws and head and psychological distress in a population-based female sample. Our main findings revealed poorer oral health-related quality of life, higher anxiety and depression, and lower sense of coherence when severe pain was reported.

Women with severe orofacial pain were not separated in terms of location, that is, muscle or joint. Studies are inconsistent about whether a difference exists in relation to psychosocial profile [Citation14,Citation29,Citation30]. The women´s experienced location of the pain was not confirmed by examination and therefore it was not suitable to make this distinction in the analysis. Also, the reported prevalence of severe orofacial pain, which encompasses chronic, long-lasting and high pain estimates, probably includes women with both peripheral and central sensitization [Citation15].

The evaluated psychological aspects had a significant relationship with orofacial pain in the cross-sectional analysis. However, the effect sizes showed low-to-moderate strength. Signs of anxiety was not significant in the regression analysis, in contrast to the OHIP score, the SOC score and signs of depression. It has been suggested that psychological distress co-exists with chronic pain and can be seen as both confounder and mediator [Citation31,Citation32]. For example, depressive symptoms might affect the way a person rate their pain, since depression is associated with negative cognitive patterns. Being exposed to pain might also enhance a depressive state. Moreover, depressive symptoms can influence the treatment outcome [Citation15,Citation32,Citation33]. The prevalence of signs of anxiety and depression in the total group was similar to that in the general female population in Sweden [Citation34,Citation35].

Further, the values of SOC-13 were consistent with other epidemiological studies [Citation36] for Swedish women of this age. Also, the severe orofacial pain group had a significantly lower mean SOC-13 score than non-cases and this finding is in line with findings in other TMD-pain studies [Citation37]. The regression model showed a significant impact of SOC on severe orofacial pain. A stronger SOC is related to a lower risk for severe orofacial pain, and it is possible to speculate that low scores reflect a poorer ability to cope successfully with pain. One point increment on the SOC scale gives an odds of 95% of the previous (lower) score adjusted for the other included independent variables. The proportion of high OHIP-5 scores in the orofacial pain group underline that pain is an important dimension of OHRQoL.

Hence, when meeting a person with pain it is important to know that they could be vulnerable regarding psychological distress, but also, that a treatment addressed towards the pain, might result in a lower impact from psychological distress. The OHIP-5 may be one of the instruments used in evaluating treatment.

Strengths and limitations of the study are that implications are limited to the observed subjects, women of this age in Sweden. Further, due to the cross-sectional design, the associations in the study cannot be seen as causal. The formed variable, severe orofacial pain, was based on questions that intentionally reflected the subjects’ own perception. The validity and reliability of the questions are not fully known [Citation22]. Another weakness was that pain from conditions other than TMD and related headache were not controlled for. The symptoms were not indifferent or transient, but care-seeking behaviour is not known. Another limitation of this cross-sectional study was that the data were collected from four cohorts, although they did not differ in relevant respects. The positive characteristics of the study, in addition to the systematic random selection, were a considerable number of attendees and an acceptable participation rate. The participation in the PSWG demanded a considerable amount of time (half a day plus time for the questionnaires), in comparison with, for example, a mail survey. It may be speculated that the results have underestimated the effects of socio-economic factors [Citation38], since income is not a known factor. The characteristics of non-participants are not fully known [Citation21]. On the other hand, the scores on the instruments included in the total group were considered similar to those in other epidemiologic studies, with respect to age and gender.

These results thus suggest that the association between TMD-related symptoms and psychological distress in the population is similar to that in comparable clinical groups [Citation11,Citation30]. One exception might be the aspect of anxiety found in care-seeking samples but not so markedly among women with symptoms in the population in this study. It is possible to speculate that this feature is linked to care-seeking behaviour. A comparison to the other limited number of population-based studies is difficult due to different questionnaires and methods [Citation4,Citation7,Citation13]. However, our results are similar to the findings by Kindler et al [Citation13] with respect to psychological distress, specifically the role of anxiety and depression in relation to pain. To draw more robust conclusions about external validity, future studies require a similar examination in a population-based group and in a patient group.

To conclude, middle-aged Swedish women, representative of the population, reported TMD-related pain and displayed psychological characteristics in line with earlier, similar investigations. Severe orofacial pain was associated with poor oral health-related quality of life and more psychological distress, thus rejecting the null hypothesis of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Okeson JP, de Leeuw R. Differential diagnosis of temporomandibular disorders and other orofacial pain disorders. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55(1):105–120.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28(1):6–27.

- List T, Dworkin SF. Comparing TMD diagnoses and clinical findings at Swedish and US TMD centers using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10(3):240–253.

- Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, et al. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(4):453–462.

- Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):354–361.

- Society IH. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211.

- Goncalves DA, Bigal ME, Jales LC, et al. Headache and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder: an epidemiological study. Headache. 2010;50(2):231–241.

- Benoliel R, Svensson P, Evers S, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic secondary headache or orofacial pain. Pain. 2019;160(1):60–68.

- Burke AL, Mathias JL, Denson LA. Psychological functioning of people living with chronic pain: a meta-analytic review. Br J Clin Psychol. 2015;54(3):345–360.

- Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, et al. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(9):T70–92.

- Manfredini D, Ahlberg J, Winocur E, et al. Correlation of RDC/TMD axis I diagnoses and axis II pain-related disability. A multicenter study. Clin Oral Invest. 2011;15(5):749–756.

- Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Greenspan JD, et al. Potential psychosocial risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain. 2011;12(11):T46–60.

- Kindler S, Samietz S, Houshmand M, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms as risk factors for temporomandibular joint pain: a prospective cohort study in the general population. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1188–1197.

- Zwart JA, Dyb G, Hagen K, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders associated with headache frequency. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(2):147–152.

- Harper DE, Schrepf A, Clauw DJ. Pain mechanisms and centralized pain in temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Res. 2016;95(10):1102–1108.

- Sanders C, Liegey-Dougall A, Haggard R, et al. Temporomandibular disorder diagnostic groups affect outcomes independently of treatment in patients at risk for developing chronicity: a 2-year follow-up study. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2016;30(3):187–202.

- John MT, Miglioretti DL, LeResche L, et al. German short forms of the oral health impact profile. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(4):277–288.

- Palla S, Farella M. External validity: a forgotten issue? J Orofac Pain. 2009;23(4):297–298.

- Bengtsson C, Blohme G, Hallberg L, et al. The study of women in Gothenburg 1968-1969–a population study. General design, purpose and sampling results. Acta Med Scand. 1973;193(1–6):311–318.

- Bengtsson C, Ahlqwist M, Andersson K, et al. The Prospective Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden, 1968-69 to 1992-93. A 24-year follow-up study with special reference to participation, representativeness, and mortality. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1997;15(4):214–219.

- Bjorkelund C, Andersson-Hange D, Andersson K, et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular risk factors with a 36-year perspective: observations from 38- and 50-year-olds in the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26(3):140–146.

- Locker D, Slade G. Association of symptoms and signs of TM disorders in an adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17(3):150–153.

- Larsson P, John MT, Hakeberg M, et al. General population norms of the Swedish short forms of oral health impact profile. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41(4):275–281.

- Wide U, Hakeberg M. Oral health-related quality of life, measured using the five-item version of the Oral Health Impact Profile, in relation to socio-economic status: a population survey in Sweden. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126(1):41–45.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

- Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass. 1987.

- Langius A, Bjorvell H, Antonovsky A. The sense of coherence concept and its relation to personality traits in Swedish samples. Scand J Caring Sci. 1992;6(3):165–171.

- Reißmann DR, John MT, Wassell RW, et al. Psychosocial profiles of diagnostic subgroups of temporomandibular disorder patients. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116(3):237–244.

- Ferrando M, Andreu Y, Galdon MJ, et al. Psychological variables and temporomandibular disorders: distress, coping, and personality. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98(2):153–160.

- Hilderink PH, Burger H, Deeg DJ, et al. The temporal relation between pain and depression: results from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):945–951.

- Gerrits MM, van Marwijk HW, van Oppen P, et al. Longitudinal association between pain, and depression and anxiety over four years. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(1):64–70.

- Gustin SM, Wilcox SL, Peck CC, et al. Similarity of suffering: equivalence of psychological and psychosocial factors in neuropathic and non-neuropathic orofacial pain patients. Pain. 2011;152(4):825–832.

- Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman A, et al. Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ. 2013;1:e98.

- Carlsson AC, Wandell P, Osby U, et al. High prevalence of diagnosis of diabetes, depression, anxiety, hypertension, asthma and COPD in the total population of Stockholm, Sweden - a challenge for public health. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):670.

- Lindmark U, Stenstrom U, Gerdin EW, et al. The distribution of ''sense of coherence'' among Swedish adults: a quantitative cross-sectional population study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(1):1–8.

- Sipila K, Ylostalo P, Kononen M, et al. Association of sense of coherence and clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23(2):147–152.

- Phillips SP, Hammarstrom A. Relative health effects of education, socioeconomic status and domestic gender inequity in Sweden: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21722.