Abstract

Aims

To evaluate limitations in jaw function, oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), and nutritional status during extensive oral rehabilitation procedures.

Material methods

Fourteen participants (mean age ± SD: 70 ± 3.8) undergoing major oral rehabilitation involving the restoration of a minimum of eight teeth were recruited in the study. Jaw function limitations scores (JFLS), oral health-impact profile (OHIP), and nutritional status were measured at different time points during, six months, and one year after the rehabilitation procedures. Nutritional status was evaluated by measuring the body weight and arm and calf muscle circumference. The effect of time points on the measured variables was evaluated with Friedman’s test. Trends in nutritional status were evaluated with linear regression analysis.

Results

The results of the analysis showed significant main effects of time points on the JLFS (p < .001) and OHIP scores (p = .005). However, there was no effect of time points on the body weight (p = .917) and calf muscle circumference (p = .424), but a significant effect on arm circumference (p = .038). Further, there was a decreasing trend for body weight (64.3%), arm (71.4%), and calf circumference (64.3%) in the majority of the patients.

Conclusion

The results of the preliminary study suggest that people undergoing extensive oral rehabilitation procedures show improvement in jaw function and an increase in OHRQoL after the rehabilitation procedure. Despite no major changes in the nutritional indicators, most patients showed a negative trend in their body weight, arm circumference, and calf circumference, suggesting that they may be susceptible to nutritional changes.

Introduction

The oral health of an individual is integral to his or her overall general health. Orofacial pain, decreased muscle strength, and tooth loss caused by caries or periodontitis affect oral health in older individuals [Citation1]. Further, excessive tooth wear can manifest as poor aesthetics, occlusal disharmony, and pulpal pathology resulting in hypersensitivity and poor chewing function [Citation2–4]. Any dysfunction in the orofacial system can affect a person’s ability to consume food and, in turn, negatively impact health and general well-being [Citation5–8]. Studies have indicated that impaired chewing function affects nutrient intake subsequently worsening the nutritional and general health status [Citation9–12]. Therefore, it is important to rebuild the damaged teeth, replace the lost teeth and thereby reinstate oral function, especially in older individuals to improve their general health and oral health-related quality of life [Citation6,Citation13,Citation14]. As chewing is an important contributor to nutrition-related factors, chewing problems may affect the nutritional status of older individuals [Citation9]

Compromised masticatory function as a result of poor dental status and lost teeth causes people to eat foods that are soft and easy to chew [Citation15,Citation16]. As a result, older individuals with compromised masticatory function tend to avoid eating raw vegetables, fruits, meat, and other food rich in nutrition and fibers that are often perceived as difficult to process. Consequently, these people are more likely to develop nutritional deficiencies because of decreased supply of key nutritional ingredients.

Research has shown that oral rehabilitation or prosthodontic procedures in general can restore jaw function [Citation17,Citation18], improve oral health-related quality of life [Citation19], and may affect nutritional status [Citation20]. Studies have also shown that dental implants and fixed prostheses help in the improvement of jaw function and quality of life in older adults [Citation21–23]. Major oral rehabilitation procedures that involve the restoration of multiple teeth are typically long and extensive and require several visits to the dentist. The treatment plan usually involves extraction of root stumps, restoration of caries, endodontic treatments, placement of implants, healing time, and finally crowns or construction of bridges. At times the patients are complemented with a temporary restoration to retain the oral functions and esthetics. A major oral rehabilitation can typically last for about 6–18 months depending on the severity and compliance of the patients. It is often the case that the patients tend to complain about their temporary constructions and associated complaints regarding masticatory dysfunction, even though they have been rehabilitated with temporary dental structures. Previous studies have investigated the effect of oral rehabilitation/prosthodontic procedures on function, nutritional status, and oral health-related quality of life [Citation24–26]. However, there are no studies to the best of our knowledge that describe the dynamic changes in nutritional indicators, jaw function, and quality of life during major oral rehabilitation procures. Since oral rehabilitation procedures, are long and tedious, involving multiple steps the patients undergoing these procedures may temporarily experience adverse effects on their general health and nutritional status. Therefore, the aims of this preliminary pilot study were to evaluate the changes in limitations in jaw function, oral health-related quality of life, and nutritional status, during major oral rehabilitation procedures. We hypothesized that people undergoing extensive oral rehabilitation procedures will present changes in nutritional status, and report limitations in jaw function and poor oral health-related quality of life. We also hypothesized that there will be an improvement in jaw function, oral health-related quality of life, and nutritional status after the oral rehabilitation procedures.

Material and methods

Study location

The study participants were patients referred to the Institute for Postgraduate Dental Education, Jönköping, Sweden (Odontologiska Instutitionen) for prosthetic rehabilitation between September 2018 and January 2022. All clinical examinations and the subsequent oral rehabilitation procedures took place at the Prosthetic Dentistry Department by Specialists in prosthodontics and Postgraduate dental consultants.

Study participants

A convenient sample of fourteen participants (mean age ± SD: 70 ± 3.8, range of 61–74 years) that included six women and 8 men were recruited in the current pilot study group. Participation in the study was voluntary and the participants were explained both the experimental and the treatment protocol. The participants could only be included in the study if they gave both verbal and written informed consent. The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki II and was approved by the regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (D-nr 2018/531-31/1). The participants were eligible to participate in the study if the indicated treatment included a temporary restoration that replaces a minimum of eight teeth. Other inclusion criteria included that the participants were in good general health as classified by the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) classes I and II and the participants lead an independent life without any need for assistance for their day-to-day chores. Also, good Swedish reading and writing language skills were mandatory for inclusion in the study. The participants were excluded if they were on any special diet for weight loss or any other reason or presented a history of or ongoing signs and symptoms of cognitive decline, acute or chronic systemic diseases, and psychological illness.

The need for major rehabilitation procedures differed among patients but, overall, involved rehabilitating a minimum of eight teeth. The treatment procedures involved the extraction of root stumps or teeth with poor prognoses, tooth preparation for crowns and bridges, surgical crown lengthening, placement of dental implants, composite restorations, etc. Additionally, all participants were provided with temporary prostheses; however, the length of the treatment procedure and the duration of temporary restoration varied among different patients.

Study protocol

The data was collected by one of the authors (TT) who was not involved in any treatment procedure and was assisted by a dental assistant to accomplish all the final measurements. The specific time points were baseline (before treatment started) and at regular intervals of about 3–6 weeks until the final prosthesis was restored (final prosthesis). The majority (78%) of the participants had a minimum of seven recalls after the baseline and until the final prosthesis was delivered. Further, the participants were recalled six months (71%) and one year (57%) after completion of the treatment for further assessments. Overall, all participants (100%) could be followed until their last recall of their oral rehabilitation procedure.

Measurements

The limitations of jaw function and oral health-related quality of life were assessed using the Swedish version of the jaw function limitation scale (JFLS) and oral health impact profile (OHIP) questionnaire at different time points [Citation27,Citation28]. The nutritional status was evaluated by measuring the anthropometric measurements related to body weight, and arm and calf circumference at baseline, and subsequent follow-ups during and after the treatments. The body weight was measured with a digital weighting scale. The participants were asked to step on a weighing scale without their shoes and their body weight was recorded. The mid upper arm circumference was measured at the midpoint between the tip of the shoulder and the tip of the elbow using a measuring tape [Citation29]. Similarly, the calf muscle circumference was the largest calf circumference measured using a standard measuring tape. These anthropometric measurements are relatively inexpensive, useful tool for a fast assessment of the nutritional status and have been used in the previous studies as reliable indicators of nutrition status [Citation9,Citation30].

Statistical analysis

The data were tested for the assumptions of normal distribution by subjecting the continuous variables to the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data appeared to be skewed and was not normally distributed as confirmed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Hence the non-parametric test was applied for statistical analysis. The effect of time points on JFLS, and OHIP scores, body weight, and arm and calf muscle circumference were tested with the Friedman test. If there was a significant main effect, then post hoc comparisons were done with multiple Wilcoxon Signed Ranks tests where each time point was compared to the baseline. The trends in the anthropometric measurements for each patient in each of the measurements were evaluated with linear regression analysis. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

On an average the total number of natural teeth was 19 ± 5.8 before the treatment and 15 ± 6.5 after the treatment. Further the mean number of ‘functional teeth’ (all teeth including fixed prosthesis) increased from 15.7 ± 10.9 to 24.3 ± 3.2 after the treatment in the patient group. As mentioned, the participants were given a temporary/intermediate restoration during the treatment until the final restoration of the prosthesis. Please see for details. Further, two patients (14%) were treated with the shortened dental arch (SDA) concept and vertical dimension of occlusion (VDO) was raised in about eleven (78%) of the participants in the study.

Table 1. Showing distribution of the temporary and permanent restorations in the patient group.

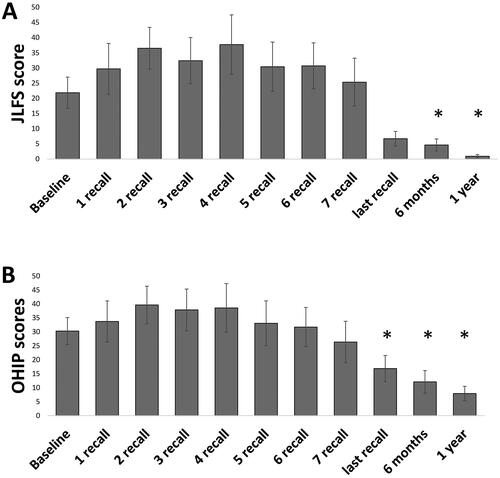

The results of the statistical analysis showed significant main effects of time points on the JLFS (p < .001) and OHIP scores (p = .005). Post-hoc analysis of the main effects of the JLFS showed significantly lower scores at six months and one-year follow-ups compared to the baseline scores (p < .021) (). Similarly, post-hoc analysis of the main effects of the OHIP showed significantly lower scores at the last recall, six months, and one-year follow-up compared to the baseline scores (p < .046) ().

Figure 1. Figure showing mean and standard deviation of scores of (A) Jaw Function Limitation Scale and (B) Oral Health Impact Profile at different time points.

Asterisks indicate significant differences between the specific time points and baseline.

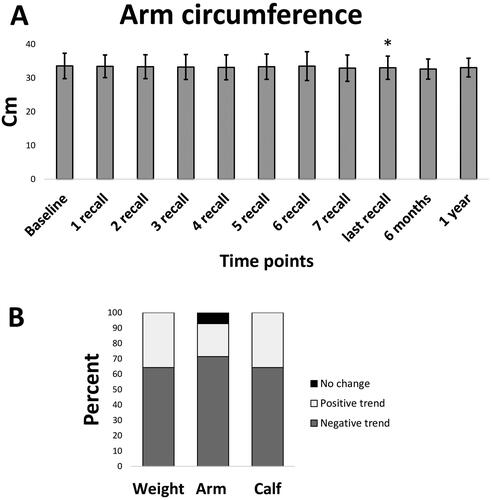

The results of the analysis also showed that there was no significant main effect of time points on body weight (p = .917) and calf muscle circumference (p = .424). However, there was a significant main effect of time points on the arm muscle circumference (p = .038) (). Post-hoc analysis of the main effects showed that the participants had significantly lower arm circumference at the last recall compared to baseline (p < .021).

Figure 2. Figure showing the mean and standard deviation of (A) Arm circumference measurements at different time points. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the specific time points and baseline. (B) Percentage of trends.

Further, the data related to the anthropometric measurements (body weight, arm, and calf muscle circumference) were subjected to linear regression analysis to evaluate the trends. A negative slope indicated a decrease in the anthropometric measurement with an increase in time points while a positive slope indicated an increase in the anthropometric measurement with an increase in time points. The results of the analysis showed a decreasing trend for body weight (64.3%), arm (71.4%), and calf circumference (64.3%) in the majority of the patients. Only 35.7% of patients for body weight, 21.4% of patients for arm, and 35.7% of patients for calf muscle circumference showed positive trends with time points ().

Discussion

The current study evaluated limitations in jaw function, oral health-related quality of life, and nutritional status of patients undergoing major oral rehabilitation involving the restoration of at least eight teeth. The results of the study showed severe limitations in jaw function and poor oral health-related quality of life, as reflected in JFLS and OHIP scores, during the course of the restoration/rehabilitation procedures. The results also showed a significant improvement in jaw function and oral health-related quality of life about six months after the rehabilitation procedures. However, the nutritional status, as measured by body weight and calf muscle circumference, did not change during the rehabilitation procedures. Furthermore, the results showed a significant decrease in arm circumference at the last recall of the rehabilitation procedure compared to baseline and a negative trend in body weight, arm, and calf circumference in the majority of the patients after the treatment, indicating poor nutritional status as a result of the procedure. The preliminary results imply that people undergoing major oral rehabilitation procedures may report better jaw function and oral health-related quality of life after the treatment but may also be susceptible to changes in nutritional status.

Oral rehabilitation procedures have been shown to improve oral functions and oral health-related quality of life. Although chewing function is seldom optimal in a significant fraction of cases or groups, patients report satisfaction with their OHRQoL [Citation23,Citation31,Citation32]. The results of the current study show obvious limitations in jaw function and OHRQoL at baseline. Additionally, the results of the current study show an instinctive improvement in jaw function and OHRQoL six months to one year after oral rehabilitation procedures. Specifically, the patients reported lower to (almost) no limitation in jaw function after six months of oral rehabilitation procedures. Similarly, the OHIP scores showed a decrease at the last recall session, indicating that patients tended to perceive less dysfunction, discomfort, and disability, and lesser handicapped associated with oral disorders. The results are in accordance with the previous findings that report a better jaw function [Citation23] and improvement in oral health-related quality of life after prosthodontic/rehabilitation procedures [Citation23,Citation33].

Nutritional assessments are the interpretation of the data that determines whether an individual (or a group) is adequately nourished or malnourished. Previous studies have reported body weight (BMI), arm, and calf circumference as routine clinical indicators of nutritional status [Citation34,Citation35]. Previous studies have also suggested that body BMI, arm, and calf circumference are reliable parameters to determine nutritional status and nutritional risk in hospitalized older adults [Citation34,Citation36]. In the current study, we observed no significant changes in body weight and calf muscle circumference, during and up to one year after the rehabilitation procedures. However, the results also indicate that there was a negative trend in body weight, arm, and calf circumference in the majority of the patients. It is suggested that unintentional weight loss is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in older people. In particular, there is an increased risk of mortality associated with weight loss of about 5% in a year [Citation37]. It is also suggested that smaller weight loss can be critical in frail patients [Citation38]. However, the participants in the current study majorly showed no changes in the indicators of nutrition. While the trend, analysis shows a slightly decreasing trend in the body weight, arm, and calf circumference. It has been observed that prosthodontic patients rehabilitated with bimaxillary implant-supported fixed prostheses perform poorly in the masticatory performance tests [Citation32] despite reporting no limitation in their jaw function and oral health related quality of life [Citation23]. However, does impaired function affect the nutritional status or general health is a question that needs to be investigated. In the current study, it was observed that despite no severe jaw limitations and an improvement in oral health-related quality of life, participants’ nutritional status was affected by the relatively longer treatment procedures. The findings mean that the patients undergoing extensive (oral) rehabilitation may be susceptible to changes in nutritional status [Citation39]. However, it is also observed that these patients tend to recover once the treatment has been completed and the patients have adapted to their new oral environment. Although these subtle changes in nutrition indicators are not alarming, they may be considered during treatment planning to maintain the nutritional status of people undergoing major rehabilitation procedures.

Previous original research studies and systematic reviews have suggested that there is weak evidence that prosthodontic treatment can improve dietary intake [Citation40,Citation41]. Therefore, these tendencies of decrease in indicators of nutrition can manifest as nutritional deficiencies as the participant ages. These manifestations can also result in poor general health and diseases related to nutritional deficiencies. It is also suggested that a majority of patients may adapt to the altered oral environment and improve their nutritional status and general quality of life. However, it is also likely that a minority of the patient is unable to adapt to the altered oral environment and may find it difficult to adapt to the new oral status and manifest malnutrition, sarcopenia, or other comorbidities. It has been recently suggested that chewing is an important contributor to swallowing function, digestive processes, and nutritional status [Citation9]. Therefore, efforts should be made to optimize oral functions after oral rehabilitation procedures and improve nutritional status in patients that have undergone extensive oral rehabilitation procedures. Further, other screening tools such as Mini nutritional assessment score, ‘Seniors in the Community: Risk Evaluation for Eating and Nutrition (SCREEN) or other nutritional blood biomarkers (e.g. Carotenoids) may be better indicators of nutritional status in these group of patients. The combination of oral rehabilitation with dietary intervention is recommended to improve dietary intake in older adults [Citation41,Citation42]. Similarly, it is suggested that older people undergoing major oral rehabilitation procedures may perhaps benefit from dietary advice or dietary supplements that are customized for this group. These interventions will help the participants to recover rapidly or maintain their nutritional status during the long and at times invasive oral rehabilitation procedures.

It is quite evident that clinical studies often have limitations, so it is important to acknowledge them. The current study involved a long exhaustive process of data collection that involved the compilation of different measurements at different time points and keeping track of all the participants. In the current study, the inclusion criteria were people undergoing a minimum rehabilitation of 8 teeth. Most participants had at least seven definite appointments during their treatment, although treatment time, provisional/temporary prosthesis duration, and type of oral rehabilitation differed from person to person. Further, the current study had no sample size calculation performed before the start of the study. Therefore, the results of the current study should be treated with caution and no firm conclusions may be made. The current study is a preliminary pilot attempt with a relatively smaller sample to finalize the protocols for future longitudinal studies. However, the statistical test used for the analysis of the nonparametric data is quite conservative therefore these results may be preliminary indications for developing a stronger hypothesis.

Conclusion

The results of the current preliminary study suggest that people undergoing extensive oral rehabilitation procedures experience limitations in jaw function and poor OHRQoL during the treatment. However, there is an obvious improvement in jaw function and an increase in OHRQoL after the rehabilitation procedure. Additionally, despite no major changes in body weight and calf muscle circumference, there was a significant decrease in arm circumference at the last recall session of the rehabilitation procedure, compared with baseline. Further, a negative trend was also observed in body weight, arm circumference, and calf circumference in the majority of patients, indicating that they may be susceptible to nutritional changes during and after treatment.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (D-nr 2018/531-31/1) following the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants were given both verbal as well as written information about this study and informed written consent was obtained. Also, participants were informed that if they wished to discontinue the study, they could do so at any point.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

TT collected and complied with the data and drafted the first draft together with AK. AK contributed to the conception and design of the study, the compilation and statistical analysis of the data, and the preparation of the figures and the final draft. CG was involved in the data collection and provided critical suggestions in the conception and finalization of the manuscript. The study was conceived, designed, implemented, and critically revised by AG who was responsible for the overall supervision of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

On reasonable request, the corresponding author (AK) will provide the datasets used in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello AL, Barrios R, et al. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–467. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S54630.

- Addy M. Tooth brushing, tooth wear and dentine hypersensitivity–are they associated? Int Dent J. 2005;55(4 Suppl 1):261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00063.x.

- Jain V, Mathur VP, Kumar A. A preliminary study to find a possible association between occlusal wear and maximum bite force in humans. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71(1):96–101. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2011.654246.

- Sterenborg BA, Kalaykova SI, Loomans BA, et al. Impact of tooth wear on masticatory performance. J Dent. 2019;82:101–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.01.003.

- Gellrich NC, Handschel J, Holtmann H, et al. Oral cancer malnutrition impacts weight and quality of life. Nutrients. 2015;7(4):2145–2160. doi: 10.3390/nu7042145.

- Göthberg C. On loading protocols and abutment use in implant dentistry. Clinical studies. [Doctor of Philosophy (Medicine)]. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. Sahlgrenska Academy; 2016.

- Grigoriadis A, Kumar A, Åberg MK, et al. Effect of sudden deprivation of sensory inputs from periodontium on mastication. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:1316–1316. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01316.

- Larsson P, List T, Lundstrom I, et al. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-S). Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62(3):147–152. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001496.

- Kumar A, Almotairy N, Merzo JJ, et al. Chewing and its influence on swallowing, gastrointestinal and nutrition-related factors: a systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;2022:1–31. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2098245.

- Kwok T, Yu CN, Hui HW, et al. Association between functional dental state and dietary intake of chinese vegetarian old age home residents. Gerodontology. 2004;21(3):161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2004.00030.x.

- Kwon J, Suzuki T, Kumagai S, et al. Risk factors for dietary variety decline among japanese elderly in a rural community: a 8-year follow-up study from TMIG-LISA. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(3):305–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602314.

- Nordenram G, Ljunggren G, Cederholm T. Nutritional status and chewing capacity in nursing home residents. Aging. 2001;13(5):370–377. doi: 10.1007/BF03351505.

- Kumar A, Kothari M, Grigoriadis A, et al. Bite or brain: implication of sensorimotor regulation and neuroplasticity in oral rehabilitation procedures. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(4):323–333. doi: 10.1111/joor.12603.

- Polzer I, Schimmel M, Müller F, et al. Edentulism as part of the general health problems of elderly adults. Int Dental J. 2010;60(3):143–155.

- Almotairy N, Kumar A, Grigoriadis A. Effect of food hardness on chewing behavior in children. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(3):1203–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03425-y.

- Cichero JAY. Age-related changes to eating and swallowing impact frailty: aspiration, choking risk, modified food texture and autonomy of choice. Geriatrics. 2018;3(4):69. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3040069.

- Iwaki M, Kanazawa M, Sato D, et al. Masticatory function of immediately loaded two-implant mandibular overdentures: a 5-year prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019;34(6):1434–1440–1440. doi: 10.11607/jomi.7565.

- van der Bilt A, Burgers M, van Kampen FM, et al. Mandibular implant-supported overdentures and oral function. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21(11):1209–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01915.x.

- Thalji G, McGraw K, Cooper LF. Maxillary complete denture outcomes: a systematic review of patient-based outcomes. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2016;31(Suppl):S169–S181. doi: 10.11607/jomi.16suppl.g5.1.

- Savoca MR, Arcury TA, Leng X, et al. Impact of denture usage patterns on dietary quality and food avoidance among older adults. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;30(1):86–102. doi: 10.1080/01639366.2011.545043.

- Bakke M, Holm B, Gotfredsen K. Masticatory function and patient satisfaction with implant-supported mandibular overdentures: a prospective 5-year study. Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15(6):575–581.

- Heydecke G, Boudrias P, Awad MA, et al. Within-subject comparisons of maxillary fixed and removable implant prostheses. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14(1):125–130. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.140117.x.

- Homsi G, Karlsson A, Almotairy N, et al. Subjective and objective evaluation of masticatory function in patients with bimaxillary implant-supported prostheses. J Oral Rehabil. 2023;50(2):140–149. doi: 10.1111/joor.13393.

- Amagai N, Komagamine Y, Kanazawa M, et al. The effect of prosthetic rehabilitation and simple dietary counseling on food intake and oral health related quality of life among the edentulous individuals: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent. 2017;65:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.07.011.

- Goncalves T, Campos CH, Garcia R. Effects of implant-based prostheses on mastication, nutritional intake, and oral health-related quality of life in partially edentulous patients: a paired clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2015;30(2):391–396. doi: 10.11607/jomi.3770.

- Komagamine Y, Kanazawa M, Iwaki M, et al. Combined effect of new complete dentures and simple dietary advice on nutritional status in edentulous patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):539. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1664-y.

- Oghli I, List T, John M, et al. Prevalence and oral health-related quality of life of self-reported orofacial conditions in Sweden. Oral Dis. 2017;23(2):233–240. doi: 10.1111/odi.12600.

- Oghli I, List T, John MT, et al. Prevalence and normative values for jaw functional limitations in the general population in Sweden. Oral Dis. 2019;25(2):580–587. doi: 10.1111/odi.13004.

- Stephens K, Escobar A, Jennison EN, et al. Evaluating mid-upper arm circumference Z-Score as a determinant of nutrition status. Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33(1):124–132. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10018.

- Khadivzadeh T. Mid upper arm and calf circumferences as indicators of nutritional status in women of reproductive age. East Mediterr Health J. 2002a;8(4-5):612–618. doi: 10.26719/2002.8.4-5.612.

- Fonteyne E, Matthys C, Bruneel L, et al. Articulation, oral function, and quality of life in patients treated with implant overdentures in the mandible: a prospective study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2021;23(3):388–399. doi: 10.1111/cid.12989.

- Homsi G, Kumar A, Almotairy N, et al. Assessment of masticatory function in older individuals with bimaxillary implant-supported fixed prostheses or with a natural dentition: a case-control study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;129(6):871–877. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.08.023.

- Ali Z, Baker SR, Shahrbaf S, et al. Oral health-related quality of life after prosthodontic treatment for patients with partial edentulism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2019;121(1):59–68.e53. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.03.003.

- Aparecida Leandro-Merhi V, Luiz Braga de Aquino J, Gonzaga Teixeira de Camargo J. Agreement between body mass index, calf circumference, arm circumference, habitual energy intake and the MNA in hospitalized elderly. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(2):128–132. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0098-1.

- Khadivzadeh T. Mid upper arm and calf circumferences as indicators of nutritional status in women of reproductive age. East Mediterr Health J. 2002b;8(4–5):612–618.

- Leandro-Merhi VA, De Aquino JL. Anthropometric parameters of nutritional assessment as predictive factors of the mini nutritional assessment (MNA) of hospitalized elderly patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(3):181–186. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0116-8.

- McMinn J, Steel C, Bowman A. Investigation and management of unintentional weight loss in older adults. BMJ. 2011;342(mar29 1):d1732–d1732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1732.

- Alibhai SMH, Greenwood C, Payette H. An approach to the management of unintentional weight loss in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172(6):773–780. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031527.

- Gaddey HL, Holder K. Unintentional weight loss in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(9):718–722.

- Kimura-Ono A, Maekawa K, Kuboki T, et al. Prosthodontic treatment can improve the ingestible food profile in Japanese adult outpatients. J Prosthodont Res. 2023;67(2):189–195. doi: 10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_22_00017.

- McGowan L, McCrum LA, Watson S, et al. The impact of oral rehabilitation coupled with healthy dietary advice on the nutritional status of adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(13):2127–2147. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1630600.

- Wallace S, Samietz S, Abbas M, et al. Impact of prosthodontic rehabilitation on the masticatory performance of partially dentate older patients: can it predict nutritional state? Results from a RCT. J Dent. 2018;68:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.11.003.