Abstract

Background

Degree of distress perceived due to tinnitus is different in every individual. Underlying mechanisms for this are yet unclear.

Objective

Investigating the relationship between hearing status and tinnitus distress.

Material and methods

This is a case-control study. 38 individuals with tinnitus, divided into normal hearing (NHT, n = 19) and hearing impaired (HIT, n = 19) groups. Groups were age- and sex matched, had similar educational background, tinnitus duration and lateralization. Participants underwent audiometric evaluation (0.125 to 16 kHz), completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI).

Results

NHT group showed significantly lower degrees of tinnitus distress compared to HIT group (p = .021), and THI score was positively correlated with mean tinnitus sided hearing thresholds at 0.5–4 kHz (r = 0.420, p = .012) when corrected for sex, age and educational background.

Conclusions

The present study suggests hearing status may play critical role for experienced tinnitus distress, even in individuals with mild to moderate hearing impairment.

Significance

This is the first study to investigate the relationship between behavioral hearing ability and tinnitus distress when controlling for age, sex, educational background and age at tinnitus onset. The results provide important information regarding management of tinnitus patients.

Chinese abstract

背景:每个人因耳鸣而感到的痛苦程度都不尽相同, 其潜在机制尚不清楚。

目的:探讨听力状态与耳鸣困扰的关系。

材料和方法:这是一项病例-对照研究。 38名耳鸣患者, 分为正常听力(NHT, n¼19)组和听力障碍(HIT, n¼19)组。两组年龄和性别匹配, 具有相似的教育背景、耳鸣持续时间和偏侧性。参加者进行了听力测评(0.125至16 kHz), 完成了医院焦虑和抑郁量表(HADS)和耳鸣障碍清单(THI)。

结果:与HIT组相比, NHT组的耳鸣困扰程度明显更低(p¼.021);针对性别、年龄和教育背景进行调整后, THI评分与0.5–4 kHz时平均耳鸣侧听力阈值呈正相关(r¼0.420, p¼.012)。

结论:本研究表明, 即使对于轻度至中度听力障碍的人, 听力状态也可能对所遭受的耳鸣困扰起关键作用。

意义:这是探讨在控制年龄、性别、教育背景和耳鸣发作年龄时行为听觉能力与耳鸣困扰之间关系的首次研究。其研究结果提供了关于耳鸣患者治疗的重要信息。

Introduction

The distress caused by tinnitus is different for every individual, for some the constant ringing in the ears can be a personal tragedy with major negative impact on quality of life, while others are not bothered at all. Tinnitus is a very common condition with prevalence figures among adults ranging from 5 to 43%, but experiencing bothersome tinnitus is seen in 3 to 31% among adults [Citation1]. Specifically, sufferers commonly report complications due to tinnitus such as problems falling asleep, depression, anxiety and concentration difficulties [Citation1].

It is not fully understood what affects the degree of tinnitus distress experienced by the individual. At first glance, an intuitive assumption may be that louder tinnitus could lead to more severe degrees of tinnitus distress. Results in line with this hypothesis has been reported by some researchers [Citation2]. However, more recent research shows that severe tinnitus loudness can be associated with low tinnitus distress and vice versa and concludes that subjective tinnitus loudness and tinnitus distress are in fact discrepant aspects of the phantom sound experience rather than one being a consequence of the other [Citation3,Citation4]. In line with this, researchers have reported tinnitus loudness and tinnitus distress to be associated with different types of oscillatory brain characteristics [Citation5]. Schlee and colleagues [Citation6] conducted a questionnaire study which indicated that older age at tinnitus onset may result in worse tinnitus distress, which could be due to the decline in compensatory brain plasticity with increasing age. In order to exclude the potential impact of hearing status on the results, Schlee and colleagues [Citation6] only included participants who reported no hearing impairment according to their questionnaire answers. However, as controlling for subjective experience of hearing loss is not an ideal method to control for hearing impairment [Citation7], the possible impact of hearing status on the results remains unclear.

Growing evidence suggests tinnitus distress to be a complex and heterogenic phenomenon with several possible contributing factors, rather than a result of a single attribute of the sufferers’ tinnitus [Citation3,Citation8]. Depression and anxiety are commonly identified as factors contributing to the tinnitus sufferers’ degree of distress [Citation8]. However, studies trying to identify predictors of tinnitus distress typically examine individuals post tinnitus debut, which limits the possibility to determine whether pre-existing prevalence of those psychological conditions lead to higher degrees of tinnitus distress or if the individuals are depressed and/or anxious due to their tinnitus.

Only about 10% of tinnitus sufferers have normal hearing, making hearing impairment the most common comorbidity of tinnitus [Citation9]. In addition, researchers and clinicians have reported that tinnitus patients often associate hearing-related problems with their tinnitus rather than the actual hearing loss [Citation10]. In line with this, both behavioral and neuroanatomical abnormalities previously suspected to be complications due to tinnitus have been shown to be absent when controlling thoroughly for hearing status [Citation11,Citation12]. Furthermore, among individuals with comparable audiograms, tinnitus sufferers who receive a combination of adequately fitted hearing aids and counseling show significantly greater improvement in terms of tinnitus distress 12 months post intervention, compared to tinnitus sufferers who receive counseling only [Citation13]. In the light of these findings, it seems plausible that hearing status may also play a critical role for perceived tinnitus distress.

Several researchers have tried to investigate the link between hearing loss and tinnitus distress, but the results have been conflicting. While Hiller & Goebel [Citation3] report hearing loss to be associated with higher degrees of tinnitus distress, Wallhäuser-Franke and colleagues [Citation4] present inconsistent data suggesting that hearing loss has significant effect on perceived tinnitus loudness, but not tinnitus distress. However, both of those studies have based their conclusions on the participants’ subjective experience of hearing loss, which is a considerable limitation [Citation7]. When only reviewing studies using behaviorally measures to examine hearing status, one still finds studies reporting results in line with [Citation14,Citation15] and inconsistent with [Citation16] the hypothesis that poorer hearing may be associated with greater degree of tinnitus distress.

None of the previous studies that investigated the link between hearing loss and tinnitus distress have been able to completely rule out that factors such as age or level of education have affected their results. Moreover, none of the previous studies investigating the link between behaviorally measured hearing status and tinnitus distress have controlled for age at tinnitus onset. To get a clearer picture of the relationship between hearing status and tinnitus distress, the present study will investigate whether normal hearing tinnitus sufferers and tinnitus sufferers with hearing impairment, matched for age, sex and educational background, differ in terms of subjective tinnitus distress when controlling for age at tinnitus onset.

Methods

Participants

Initially, 43 tinnitus sufferers were recruited from audiological clinics and public advertising in southern Sweden. Due to matching difficulties five of the initially recruited participants were excluded, resulting in 38 included tinnitus sufferers. These participants were divided into two groups, Normal Hearing Tinnitus Group (NHT; n = 19) and Hearing Impaired Tinnitus Group (HIT; n = 19). See for descriptive data.

Table 1. Demographic data for each group separately and all participants together.

Inclusion criterion for the NHT group was hearing thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL in best ear at 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz. Inclusion criterion for the HIT group was hearing thresholds > 20 dB HL in best ear at same frequencies. Additional inclusion criterion was to have a participant in the other group matching in terms of sex and age (differing no more than 24 months of age). All participants had similar level of education as they were all either current or former university students. No significant differences were found between the groups in terms of degree of anxiety or depression as measured by the HADS.

All participants were informed about the purpose and conduction of the study both verbally and in written text prior to participating. The study was reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board Lund, Sweden (approval number 2014/95).

Material

Measure of hearing thresholds:

All hearing assessments were carried out using a Madsen Astera2 (GN Otometrics) audiometer. All auditory stimuli were presented via HDA 200 (Sennheiser) earphones, which were calibrated with a Brüel & Kjaer 2209 sound level meter and a 4153 artificial ear.

Measure of anxiety and depression:

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [Citation17] was used to asses symptoms of anxiety and depression for each participant. This questionnaire consists of 14 statements, half covering degree anxiety (forming an anxiety subscale) and half covering degree depression (forming a depression subscale). The responder indicates to what degree each statement is applicable to themselves, which is done by selecting one out of four given response options. Responses to each statement receives a score from 0 to 3 depending on the level of anxiety/depression the response has indicated (higher scores indicating higher levels). Total score ranges from 0 to 21 for each subscale, where scores below 8 are categorized as normal levels of anxiety/depression, 8 to 10 are categorized as borderline, and scores higher than 10 are categorized as clinical levels of anxiety/depression [Citation17].

Measure of tinnitus distress:

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) [Citation18], which is widely used in both clinic and research, was used to assess the distress caused by tinnitus for each participant. This questionnaire consists of 25 questions regarding tinnitus (e.g. Do you feel that you can no longer cope with your tinnitus?), where every question is answered by one out of three possible options; ‘Yes’ (providing a score of 4 points), ‘Sometimes’ (providing a score of 2 points) and ‘No’ (providing a score of 0 points). This sums up to a total score of 0 to 100 points, where scores of 0–16 indicate no handicap, 18–36 indicate mild handicap, 38–56 indicate moderate handicap and 58–100 indicate severe handicap due to tinnitus.

Procedure

The entire procedure was conducted in a sound treated room. First, all participants underwent otoscopy and had their pure tone hearing thresholds assessed at frequencies of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz. Thereafter, participants completed the Swedish versions of HADS and THI and underwent a brief interview regarding their tinnitus experience. The interview included open questions regarding tinnitus duration and lateralization.

Data analysis

An ANCOVA was conducted to determine whether NHT differed from HIT in terms of THI score when controlling for age at tinnitus onset. Furthermore, two partial correlation calculations were performed in order to determine whether hearing impairment at specific frequencies may be associated with greater tinnitus distress; one between THI score and between tinnitus sided PTA at 0.5–4 kHz, and a second between THI score and tinnitus sided PTA at 10–16 kHz. In participants with unilateral tinnitus, PTA of tinnitus ear was used. In participants unable to lateralize tinnitus or with binaural tinnitus, mean PTA of both ears was used. Assumptions for ANCOVA and partial correlations were checked prior to calculations, with no findings threatening the assumptions. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0.0.0, 64-bit edition for Windows (IBM SPSS, 2016).

Results

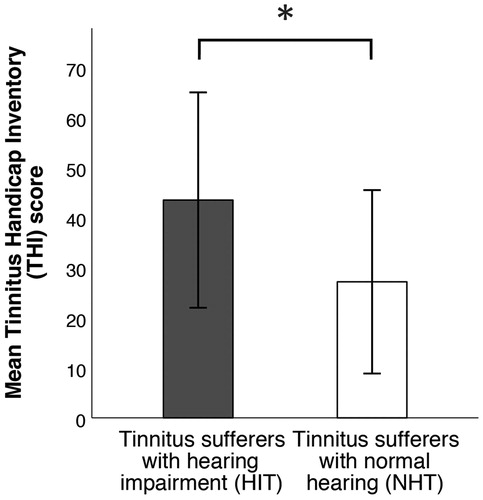

shows THI scores for tinnitus participants with normal hearing and with hearing impairment as well as for all participants together. shows mean THI score by group.

Figure 1. Difference in mean THI score between hearing impaired tinnitus participants (HIT) and normal hearing tinnitus participants (NHT). * = indicating significant difference, p-value <.05. Error bars depicting 1 standard deviation.

A one-way ANCOVA shows that there is a significant association between hearing status and THI score after controlling for age at tinnitus onset (F(1,37) = 5.851, p = .021). This relationship had a partial eta squared-value of .143. The correction for age at tinnitus onset was not significant (F(1,37) = 0.392, p = .535).

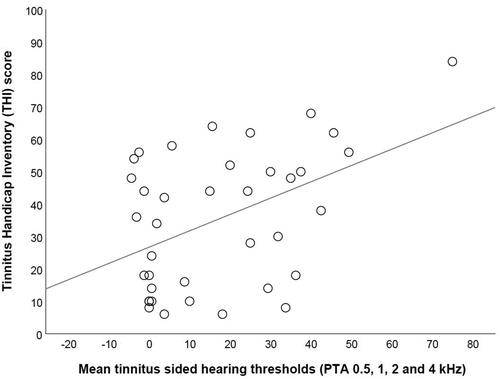

When controlling for sex, age and education on the relationship between THI score and tinnitus sided PTA at 0.5–4 kHz, we find the following significant partial correlation; r = 0.420, p = .012. When controlling for sex, age and education on the relationship between THI score and tinnitus sided PTA at 10–16 kHz, the relationship is non-significant; r = 0.220, p = .204. shows relationship between THI score and tinnitus sided PTA at 0.5–4 kHz.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed significantly lower degrees of tinnitus distress in normal hearing tinnitus sufferers compared to age-, sex- and educational level-matched tinnitus sufferers with hearing impairment when controlling for age at tinnitus onset. Furthermore, the present data show a significant positive correlation of degree of tinnitus distress and mean tinnitus sided hearing thresholds (i.e. the poorer hearing thresholds, the higher degree of tinnitus distress) at 0.5–4 kHz, but not at 10–16 kHz. An important note is that hearing status does not alone predict tinnitus distress. Hearing status explained 14.3% of the variance in tinnitus distress among tinnitus sufferers in the present article. Thus, the present article is in line with previous research suggesting a multifactorial mechanisms explaining the amount of distress experienced by tinnitus sufferers [Citation3,Citation8].

The findings of this study is in line with the findings reported by Ratnayake et al. [Citation14] and Wang et al. [Citation15], but inconsistent with the findings of Pinto et al. [Citation16]. A possible cause for the differences between the latter study and the present may be the absence of control for educational background in in the study by Pinto and colleagues [Citation16]. Furthermore, the observed relationship between hearing status and tinnitus distress is supported by the fact that hearing aids have significant decreasing effect on tinnitus distress [Citation13], and that tinnitus sufferers commonly associate hearing related issues with their tinnitus rather than the actual hearing impairment [Citation10].

The data of the present study showed no significant effect of correcting for age at tinnitus onset on tinnitus distress, contradicting the hypothesis that decline in compensatory brain plasticity with increasing age may lead to greater tinnitus distress [Citation6]. Differences in findings may be due aforementioned limitations in attempts to control for hearing impairment; Schlee et al. [Citation6] attempted to take hearing status into account, but only by analyzing tinnitus sufferers who did not complain about hearing difficulties, which is not a fully reliable way to exclude hearing impairments [Citation7]. However, there are several other major differences between the present study and the one by Schlee et al. [Citation6] that may explain the discrepancy in results. An example of such is that Schlee et al. [Citation6] had a much larger sample size (755 tinnitus sufferers) compared to the present study (38 tinnitus sufferers). Hence, it may well be that age at tinnitus onset does in fact have an effect on tinnitus distress, but that the effect size is not large enough to show significant difference in the small sample size of the present study.

While previous research has shown high frequency hearing (particularly hearing thresholds >8 kHz) to be significantly associated with cognitive performances and neuroanatomy in tinnitus sufferers [Citation11,Citation12], the present study shows mid frequency hearing (0.5 to 4 kHz) to have significant effect on perceived tinnitus distress. This suggests that while hearing status seems to be critical to examine in tinnitus sufferers for several reasons, different types of hearing impairments may be associated with different aspects of tinnitus. This has been poorly covered in previous literature, and should be further investigated in future research projects. Hypothetically, the relationship between tinnitus distress and hearing impairment being present at 0.5–4 kHz but not at 10–16 kHz, could be due to the clearer impact on speech intelligibility of hearing impairments at 0.5–4 kHz. As speech intelligibility is a fundament for social interaction for most individuals, it is no surprise that untreated hearing impairments below 8 kHz have been associated with increased risk of social isolation [Citation19]. It is plausible that experiencing tinnitus in combination with social isolation leads to greater tinnitus distress compared to experiencing tinnitus only.

A limitation of the present study is that it has only included individuals with higher educational level and only including hearing impaired participants with mild to moderate hearing loss. On one hand, this means that hearing status has significant impact on tinnitus distress even in slight hearing impairments, but on the other hand our data does not allow us to draw any conclusions regarding how individuals with lower degrees of education or more severe hearing impairments are affected. Another limitation is that no data has been collected on what kind of interventions participants have undergone. Hearing aids is a common intervention for tinnitus sufferers which has shown significant decreasing effect on tinnitus distress [Citation13], and it is plausible that hearing aid users were more common in the hearing impaired group compared to the normal hearing group in the present study. Disregarding hearing aids when analyzing the relationship between hearing thresholds and tinnitus distress may portray the relationship as weaker than it actually is, as the distress among tinnitus sufferers with hearing impairment may have been reduced in case they have been using hearing aids.

Taken together, this study confirms the previously suspected link between hearing status and tinnitus distress. Despite those previous suspicions, some clinical guidelines do not recommend clinicians to routinely perform hearing assessments in new tinnitus patients unless certain indications (such as symptoms of vestibular schwannoma) are present [Citation20]. Apart from the results from the present study, there are several contraindications for such recommendations. E.g.:

Normal hearing is very uncommon (approximately 10%) among tinnitus sufferers [Citation9]. As the comorbidity of hearing impairment and tinnitus is very high, we should measure hearing thresholds in all tinnitus patients regardless of subjective hearing problems.

Hearing aids seem to have significant effect on degree of tinnitus distress [Citation13]. However, they have to be fitted according to the patient’s hearing, why thorough audiological examination should be recommended.

Tinnitus sufferers are often associating hearing related issues with their tinnitus rather than the actual hearing loss [Citation10]. If some of the problems our patient’s describe are due to hearing status rather than presence of tinnitus, it is important to also examine their hearing so that we can provide adequate interventions targeting the underlying cause for the problems.

The present article suggests there is sufficient evidence to make the argument that future clinical guidelines for tinnitus should include a recommendation of assessing hearing status in all new tinnitus patients.

Conclusion

There seems to be a significant relationship between hearing status and tinnitus distress when controlling for age at tinnitus onset, where poorer hearing thresholds are associated with higher degrees of tinnitus distress. This indicates hearing status to be critical for how tinnitus affects the sufferer, and that hearing assessments should be done routinely for all patients seeking health care due to tinnitus.

| Abbreviations | ||

| dB HL | = | decibel hearing level |

| HADS | = | hospital anxiety and depression scale |

| HIT | = | hearing impaired tinnitus group |

| kHz | = | kilo herz |

| NHT | = | normal hearing tinnitus group |

| PTA | = | pure tone average |

| THI | = | tinnitus handicap inventory |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Fortnum H, et al. The prevalence of tinnitus and the relationship with neuroticism in a middle-aged UK population. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(1):56–60.

- Unterrainer J, Greimel KV, Leibetseder M, et al. Experiencing tinnitus: which factors are important for perceived severity of the symptom? Int Tinnitus J. 2003;9(2):130–133.

- Hiller W, Goebel G. When tinnitus loudness and annoyance are discrepant: audiological characteristics and psychological profile. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12(6):391–400.

- Wallhäusser-Franke E, Brade J, Balkenhol T, et al. Tinnitus: distinguishing between subjectively perceived loudness and tinnitus-related distress. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34583.

- Balkenhol T, Wallhäusser-Franke E, Delb W. Psychoacoustic tinnitus loudness and tinnitus-related distress show different associations with oscillatory brain activity. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53180.

- Schlee W, Kleinjung T, Hiller W, et al. Does tinnitus distress depend on age of onset? PloS One. 2011;6(11):e27379.

- Kamil RJ, Genther DJ, Lin FR. Factors associated with the accuracy of subjective assessments of hearing impairment. Ear Hear. 2015;36(1):164–167.

- Brüggemann P, Szczepek AJ, Rose M, et al. Impact of multiple factors on the degree of tinnitus distress. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10(341):1–11.

- Sanchez TG, de Medeiros ÍRT, Levy CPD, et al. Tinnitus in normally hearing patients: clinical aspects and repercussions. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2005;71(4):427–431.

- Henry JA, Griest S, Zaugg TL, et al. Tinnitus and hearing survey: a screening tool to differentiate bothersome tinnitus from hearing difficulties. Am J Audiol. 2015;24(1):66–77. 2015

- Melcher JR, Knudson IM, Levine RA. Subcallosal brain structure: correlation with hearing threshold at supra-clinical frequencies (>8 kHz), but not with tinnitus. Hear Res. 2013;295:79–86.

- Waechter S, Wilson W, Brännström KJ. The impact of tinnitus on working memory capacity. Int J Audiol. 2020;1:1–8.

- Searchfield G, Kaur M, Martin WH. Hearing aids as an adjunct to counseling: tinnitus patients who choose amplification do better than those who don’t. Int J Audiol. 2010;49(8):574–579.

- Ratnayake S, Jayarajan V, Bartlett J. Could an underlying hearing loss be a significant factor in the handicap caused by tinnitus. Noise Health. 2009;11(44):156–160.

- Wang Y, Zhang J-N, Hu W, et al. The characteristics of cognitive impairment in subjective chronic tinnitus. Brain Behav. 2018;8(3):e00918.

- Pinto PCL, Sanchez TG, Tomita S. The impact of gender, age and hearing loss on tinnitus severity. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(1):18–24.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122(2):143–148.

- Arlinger S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss–a review. Int J Audiol. 2003;42(sup2):17–20.

- Tunkel DE, Bauer CA, Sun GH, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tinnitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(2 Suppl):S1–S40.