Abstract

This article outlines how the international push for inclusive education cannot be aligned with current education systems centred on neoliberal ideals of individualism, measurement, and competition. The way that these systems are organised means that a proportion of (usually marginalised) students are necessarily excluded. In order to meaningfully address the global education crisis, that sees millions of children and young people either out of school or unengaged with learning, this ontological misalignment must be acknowledged, and discourse and engagement around it must be promoted. Drawing from the work of Donella Meadows, I argue that ‘high leverage points’ (information flows, rules, system goals, mindsets) are crucial places to intervene in education systems. Intervention at such points, while challenging, has the potential to lead to transformational and sustainable change; change that current ‘low leverage point’ initiatives fail to produce. I conclude with a call for further discourse and research into an examination of ‘high leverage points’ within education systems, how they interact, and how the development of an associated framework would be beneficial for researchers and development partners.

Introduction

This article seeks to outline how the international push for inclusive education cannot be aligned with current, neoliberal, competition-based education systems, and why educational goals and mindsets are ‘high leverage points’ that must be addressed. I draw from the work of Gert Biesta; Araceli del Pozo Armentia et al.; Federico Waitoller; and Matthew Schuelka & Thomas Engsig who have all considered the purpose of education, and what this means for the inclusion of marginalised students. This article is also grounded in my own experience as a teacher, along with my conversations with leading educationalists on the Goal 4: Education for All podcast, and my time working with international organisations, including UNESCO, IIEP-UNESCO, and the World Bank.

I will begin by highlighting the gap between international efforts to include all students in education and the reality of the current education crisis that sees millions excluded or unengaged. I will then discuss how a rise in neoliberal education reforms, centred on a culture of measurement and competition, have led to exclusionary practice and mindsets. I argue that this is the educational paradigm that we now find ourselves in, and efforts to include marginalised students are hampered by deeply-rooted neoliberal system structures and mindsets. I will then argue, building on the work of Donella Meadows, that a ‘high leverage point’ approach is crucial if the current education crisis is to be meaningfully addressed.

The international push for inclusive education

Recent decades have seen a rise in international efforts to promote inclusive education. Initiatives such as the Salamanca Statement of 1994 and the UN’s 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, along with the current Sustainable Development Goals, have pushed an inclusive agenda within education systems around the world (Schuelka & Engsig, Citation2022). The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, Citation1994) in particular, and its focus on systemic change at the school and policy level, was an important step that sought education system reform—something that could only happen if mainstream schools adapted and became capable of including and welcoming all students.

The stated goal of inclusive education is to ensure full participation and access to quality learning opportunities for all. Importantly, the burden must not be placed on the student to ‘fit in’ to current school systems; it is education systems that must adapt to accommodate the diverse needs of all children (Global Education Monitoring Report, Citation2020; UNESCO, Citation2021).

The current education crisis

Despite inclusive education being high on the international agenda, education systems are currently failing millions of students. Even prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic, 260 million children and young people around the world were out of school (UNESCO, Citation2019b). Overwhelmingly, it is marginalised students that are most at-risk of exclusion from education, especially students with disabilities (UNICEF, Citation2021), those living in poverty (UNICEF, Citation2023), girls (OHCHR, Citation2023), and displaced people (UNHCR, Citation2023); however, there are many other—often intersecting—barriers (Global Education Monitoring Report, Citation2020; Toutain, Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2021).

Exclusion from education runs deeper than simply access to schools, however. Many students who are in schools are not receiving quality education, not being engaged in learning, and, as a result, are failing to acquire basic, life-changing skills (World Bank, Citation2019).

Highlighting this, UNICEF (Citation2022) report that, globally, nearly two-thirds of 10-year-olds are unable to read and understand simple text. It is the combination of exclusion from schools and a lack of engagement in learning that comprises the global education crisis (World Bank, Citation2019). Despite the international push for inclusive education—where all means all, and no one should be left behind (Global Education Monitoring Report, Citation2020)—huge numbers of children and young people are either not in school or, if they are, are not engaged in learning.

Why education systems exclude

I identify two main factors that can be associated with the exclusion of (particularly marginalised) students. Firstly, I examine the notion that a neoliberalist ontology has negatively impacted inclusion. Secondly, I link this to the concept of individual ‘educational excellence’, and how the measurement culture in education systems is designed to reward a select few while excluding the majority of students.

The rise of neoliberalism and its effects on education

As stated by Ball (Citation1997), neoliberalism is an economic, cultural, and political ideology for capital expansion that has had a profound effect on all aspects of life on a global scale: it is the dominant political and socio-economic paradigm of our time (McChesney, Citation1999; Monbiot, Citation2016). Neoliberalism is an ontology where individuals are viewed purely in economic terms, as ‘market-rational’ bodies who strive to increase capital and productivity (Brown, Citation2003; Waitoller, Citation2020). Importantly, as Monbiot (Citation2016) points out, neoliberalism ‘redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency’ (Par. 4). Attempts to minimise competition, says Monbiot, are seen as an attack on liberty: regulation, tax, and social welfare programmes ‘impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers’ (Par. 5). As Monbiot summarises:

Inequality is recast as virtuous […] Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve (Par. 5).

Apple (Citation2007) asserts that a key way neoliberal education reforms (and the discourse that surrounds them) have manifested themselves is the growth in the measurement of academic achievement and subsequent comparisons between students (and schools). In what Monbiot (Citation2016) describes as a paradox of neoliberalism, ‘universal competition relies upon universal quantification and comparison’; the result, he continues, is that we are ‘subject to a pettifogging, stifling regime of assessment and monitoring, designed to identify the winners and punish the losers’ (Par. 21). This has led, naturally, to a pervasive culture of measurement of competition in education: a phenomenon Mac (Citation2022) describes as ‘the free-market principles that govern the competitive educational marketplace’ (p. 10-11). Neoliberalist logic dictates that data and information allows parents to make informed choices about where to send their children, and enables governing bodies to reward or punish schools based on their performance (Apple, Citation2007).

This data-driven decision making is seen as the wonder of the free market; it is unsurprising then, notes Waitoller (Citation2020), that measurement and comparison of educational outcomes now overwhelmingly serve as an indication of the quality and availability of education. Biesta (Citation2009) concurs, stating that, in recent decades, there has been a ‘remarkable rise’ in the measurement of education, the expansion of an all-encompassing culture of measurement, and an increase in the desire to measure and compare so-called educational outcomes.

Biesta (Citation2009) argues that the measurement culture in education systems has had ‘a profound impact on educational practice, from the highest levels of educational policy at national and supra-national level down to the practices of local schools and teachers’ (p. 34). It is easy to see how measurement leads to league tables,Footnote1 which, in turn, drive competition between schools: it pays to be at the top of the table, both financially and reputationally. Even local house prices in the UK are affected by a school’s league table position (Burgess et al., Citation2020).

Due to league table pressures, there have been many documented instances of schools only accepting children they think will have a high chance of succeeding in exams—or removing certain students in the run-up to exams (e.g., Mansell, Citation2016).

But league tables are only one manifestation of the measurement culture. Ainscow (Citation2020) discusses the effect of this culture on teaching and learning, arguing that although data on educational outcomes are useful in regard to measuring progress, ‘if effectiveness is evaluated on the basis of narrow, even inappropriate, performance indicators, then the impact can be deeply damaging’ (p. 10). Reflecting on this, it becomes apparent that what we are measuring—and how it is measured—is crucial. While agreeing that, to some extent, the rise of the measurement culture in education has allowed discussions to ‘be based on factual data rather than just assumptions or opinions about what might be the case’ (p. 35), Biesta (Citation2009) notes that any decision made about this ‘factual data’ must in some way involve a value judgement—and that decisions about what ought to be done cannot logically be derived from data alone: decisions will always come down to what is ‘educationally desirable’ (p. 35).

Inclusive tensions and dilemmas of difference

Returning now to the discourse on inclusive education, I will seek to highlight tensions within it. These tensions will then be linked with the above discussion.

Pozo-Armentia et al. (Citation2020) consider the rift between the ideals and the implementation of inclusive education and identify an underlying tension: that of ontological equality vs. phenomenological inequality. Regarding the former, the authors suggest that, in line with a rights-based approach to inclusive education, all students should be treated equally and should receive the same educational opportunities. Paradoxically, this is also aligned with neoliberalist ideals: everyone should be given the same chance in life, and the ‘natural winners’ will succeed (Monbiot, Citation2016). Everyone must receive the same education, and sit the same exams. Socioeconomic background, natural diversity, parental support, etc.—the headwinds and tailwinds of life (Chavanne, Citation2018)—are ignored. Everything comes down to individual effort.

This brings us to phenomenological inequality. Pozo-Armentia et al. (Citation2020) argue that different students are, undeniably, different. Some people have different skills that make them more capable in certain contexts; this is part of what it means to be human. The authors summarise this tension: ‘One of the common sources of confusions in literature on inclusive education in the way in which the idea that we are all equal relates to the idea that we are all different’ (p. 1066). Norwich (Citation2010) describes a related dilemma of ‘whether to recognise or not to recognise differences [between students]’. Either option, he continues, ‘has some negative implications or risks associated with stigma, devaluation, rejection or denial of opportunities’ (p. 116).

These questions—when viewed in the context of the neoliberal shift towards a culture of measurement and market-style competition in education systems—are key to understanding the root of the tension identified by Pozo-Armentia et al. (Citation2020). Here, the authors point to the fact that, on an ontological level, all students should be seen as equal; however, they continue that ‘along with this equality, it is necessary to recognise inequality as the result of excellence in the performance of activities by individuals [emphasis added]’ (p. 1067). If inequality is indeed the result of individual excellence, the crucial question here is how we decide (and, indeed, who decides) who is excellent—and who is not.

Who is considered to be excellent – and why this matters for inclusion

Excellence is a social construct (Sgourev & Althuizen, Citation2017). We consider something or someone to be excellent in the context of the action being taken, and against a backdrop of our own values and the shared values of society. Thus, to be considered excellent in an educational sense a student must conform to a particular standard, based on what is valued in society. As noted above, neoliberalist movements and policies have fostered mindsets that all members of society must contribute to capital production and accumulation: people must be ‘economically useful’ to be considered of value. This invariably means that greater value is placed on Science, Technology, Engendering or Mathematics (STEM), among other ‘economically useful’ subjects. Being considered ‘excellent’ in areas such as these almost always requires succeeding in high-stakes, summative examinations and being tested against narrowly-defined indicators. ‘Successful’ students are then admitted into the universities or employment of their choice, while ‘unsuccessful’ students are not. This naturally breeds competition between students, and—fuelled by league tables—between schools themselves.

The very fact that only a certain number of students who conform to a narrowly-defined version of ‘excellence’ are rewarded by education systems (with high grades, university places, good jobs, social status, etc.) means that other, non-conforming students must necessarily be excluded. For ‘nonconforming’, read diverse needs, intellectual disabilities, marginalised students. Indeed, neoliberal education reforms, argues Potter (Citation2022), exacerbate an ‘already inequitable system in which young people with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) are considered invaluable commodities’ (p. 79).

I argue here that there is no way to align the ideals of inclusive education with education systems that are centred around measurement, competition, and narrowly-defined constructs of ‘excellence’. If we accept that all students are different—a statement that no teacher or parent would disagree with—then a system where everyone is treated equally, paradoxically, must necessarily drive inequality, pushing a wedge between those who are perceived as ‘excellent’ and those that are not.

To meaningfully approach such issues, educational goals and mindsets that necessarily exclude many students must be reconsidered.

The need for systemic change, and the power of leverage points

Systems thinking is a methodology that urges us to move away from linear thinking and to consider whole ‘systems’—their structures, rules, goals, and underpinning mindsets—in a more holistic way (Arnold & Wade, Citation2015; Meadows, Citation2001; Monat & Gannon, Citation2015; Senge, Citation2006; Stroh, Citation2015). A system can be defined as an interconnected collection of elements that is organised in a way that achieves something (Meadows, Citation2001). A collection of students, teachers, rules, school buses, assistive technologies, and mindsets—and more—interact to form an education system; a system with a goal of educating students.

Education systems are hugely complex: they are difficult to predict, constantly in flux, and are affected by an intricate network of interconnected variables (Stroh, Citation2015). In order to study systems such as these, and to affect sustainable change, their complexity must be acknowledged, as must the idea that traditional, linear approaches to change will probably fail (Green, Citation2016). With limited time and resources, efforts must be directed at certain points in the system that a) you have the power to effect, and b) are places of ‘high leverage’ that will produce transformative, system-wide change.

Meadows (Citation1999) refers to ‘leverage points’ as places to intervene in a system; points at which small changes can have far-reaching consequences. The ‘higher’ the leverage point, the greater the effect on the system. Senge (Citation2006) notes that leverage points are the ‘right places in a system where small, well-focused actions can sometimes produce significant, enduring improvements’ (p. 64). Leverage points, as stated by Nguyen and Bosch (Citation2013), exist in some shape or form in all complex systems, from national economies to education systems. However, the authors continue that, despite their prevalence—and their power—leverage points are often not intuitive and are difficult to identify.

There are ‘high’ leverage points and ‘low’ leverage points. An example of a high leverage point, put forward by Meadows (Citation1999), and noted by Hickel (Citation2021) and Raworth (Citation2017), is the goal of sustained economic growth. In perusing ‘growth at all costs’, the entire economic—and planetary—system is affected. Changes made at high leverage points have transformative—and often unexpected—effects that disrupt the entire system and, thus, can be risky places to intervene. But there is also danger in playing it safe and targeting the ‘low hanging fruit’ of development. As Abson et al. (Citation2017) state: ‘many sustainability interventions target highly tangible, but essentially weak, leverage points (i.e. using interventions that are easy, but have limited potential for transformational change)’ (p. 30). It is no surprise that highly tangible interventions are prised by governments and donors: measurable impact is crucial in securing, and justifying, funding. As Green (Citation2016) points out: ‘in the development arena, donors often accentuate the penchant for short-termism by demanding tangible results within the timescales of project funding cycles’ (p. 20).

The problem with making changes at these ‘weak’, or ‘low’, leverage points is that such efforts are usually unsustainable. This is because small changes are overwhelmed by the momentum of the entire system and are quickly snuffed out—this is analogous to creating a small eddy in a river: it will be visible at the surface, but will only last for a short while before being washed downstream. As Pirsig (Citation1999) warns us:

If a revolution destroys a systematic government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves in the succeeding government (p. 101).

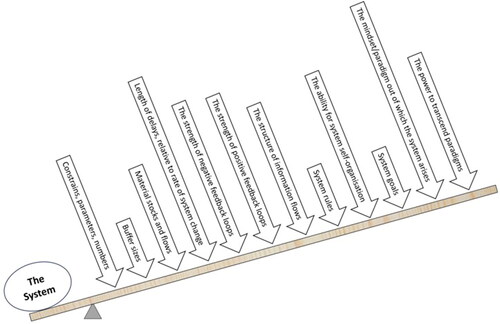

In a seminal article, Meadows (Citation1999) outlines 12 leverage points as ‘places to intervene in a system’. These are presented in .

Figure 1. Meadows’ leverage points, inspired by Rising (Citation2015).

Low leverage points (Constraints, parameters, numbers; buffer sizes; stocks and flow structures) are the places most often targeted by development initiatives. Examples might be increases in school funding, the number of newly trained teachers, etc. These initiatives are important and should continue; however, as argued by Meadows, they are relatively ineffectual: if the system is designed in a certain way, with certain goals underpinned by deep-rooted mindsets, these changes will, naturally, be unsustainable.

The further we look to the right of the diagram, the higher the leverage points become. For instance, ‘system rules’ are a relatively high leverage point: a relevant example of system rules relating to inclusive education are ratified international agreements that make it a legal requirement to include all students in schools. Another system rule in many schools makes it a requirement for all students to sit standardised exams at the end of each semester. Adapting either such rules would likely lead to transformative, system-wide change (Groce, Citation2018). However, as Meadows argues, if system goals, and wider societal mindsetsFootnote2—leverage points to the far right of the diagram—are in opposition, system rules will always be under wider systemic pressures.

An entire system is shaped by its goals. Education goals affect every other aspect of the education system: if the goal is to promote individual excellence, based on narrowly-defined indicators, and related to what is considered ‘valuable’, then the entire system—school design, teacher training, modes of learning and assessment, the ability (or willingness) to accommodate students with diverse needs—will naturally coalesce around this.

System goals themselves arise from the mindsets of societies. The ‘great big unstated assumptions—unstated because unnecessary to state; everyone already knows them’, as Meadows (p. 17) puts it.; the ‘known’ beliefs that constitute a society’s paradigm:Footnote3 Economic growth is good, one can ‘own’ land, human beings have ‘rights’. And, that inequality is virtuous - the market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

Neoliberalist mindsets are so entrenched in our society, so deeply rooted, they are hardly ever debated and almost never questioned; indeed, as Monbiot (Citation2016) states, ‘the ideology that dominates our lives has, for most of us, no name’ (Par. 1). We accept, concludes Monbiot, that ‘this utopian, millenarian faith describes a neutral force; a kind of biological law, like Darwin’s theory of evolution’ (Par. 3). Neoliberalist ideals of individualism and free-market forces—that there is an inherent difference between ‘natural winners and losers’, and that it is economically inefficient to support the latter—have naturally shaped education system goals and, thus, every other aspect of those systems.

Changing mindsets

The neoliberal mindsets that shape education systems are, by definition, exclusionary. I argue here that these are directly at odds with the international push for inclusive education; expecting full inclusion to occur in neoliberal, competition-based education systems is akin to asking communism and free-market capitalism to both thrive in the same economic system. Until this is acknowledged and explored—until we step away from systems designed around individualism and competition—education will remain exclusive in its very nature.

So, how do you change mindsets? Resistance to new ideas, vested interests, fear of uncertainty and the challenge of shifting established norms—Spady’s (1998) ‘systemic inertia’—are all barriers to contend with. Thomas Kuhn (Citation1962) famously wrote about what he referred to as the great paradigm shifts of science: Khun suggested the continued highlighting of current paradigm failures, public assurances of the benefits of the new one, and the insertion of ‘new paradigm people’ into positions of power and influence. This works, perhaps, when a new paradigm is lined up and ready to go (for example, the paradigm shift in physics towards quantum mechanics in the early twentieth century); however, what happens when there is no viable alternative prepared? The new paradigm of inclusive education, though morally just, is far from agreed upon in terms of how it should be implemented (Haug, Citation2017). Indeed, as Monbiot (Citation2016) suggests, ‘it’s not enough to oppose a broken system. A coherent alternative has to be proposed’ (Par. 43). (Depending on context, this alternative could arise from anywhere. It is important to acknowledge, that what works in one education system may not necessarily work in another—further highlighting the importance of local expertise, system autonomy, and participatory approaches.)

Wherever the education (and societal) paradigm shift comes from, and whenever this happens—because, if history teaches us anything, it is that no paradigm lasts forever—it will rely on a concerted and coordinated effort of activists, researchers, politicians, international organisations, schools, parents, students, and other stakeholders. For this to happen, educational goals (and system structures) must be explored and discussed now; wider-reaching public engagement is needed on the pitfalls of the current education system and the depth of its exclusionary nature; respected and influential figures must not only support the push for inclusion, but must be made aware that high leverage, systemic change is needed. The academic and development community should debate the current adversity between inclusive ideals and current neoliberalist education system structure, and engage with decision makers and those with power in the system (e.g. politicians, members of the media, community leaders) in productive research and discourse around high leverage points; at places where intervention will have transformative, sustainable, systematic impact. In relation to the inclusive education agenda, we must ask: What, exactly, are students being included into? And, just as importantly, who is doing the including? An examination of power structures (Green, Citation2016) and conversations around ‘critical inclusion’ (Ahmed, Citation2020; Bourassa, Citation2021) should be brought to the debate.

And, finally, we must acknowledge that current education systems are created by humans, and can be changed by humans: all we must do is let go of our some of our most deeply held assumptions and world views—certainly no easy task. However, as Meadows puts it:

Surely there is no power, no control, no understanding, not even a reason for being, much less acting, in the notion or experience that there is no certainty in any worldview. But, in fact, everyone who has managed to entertain that idea, for a moment or for a lifetime, has found it to be the basis for radical empowerment (p. 19).

Concluding thoughts

This is a call to acknowledge the fundamental problems with how education systems are structured, their goals, and the deeply-held, sociopolitical mindsets that drive such goals—and how these are misaligned with the international push for inclusion. This is certainly not a call to stop targeting specific areas within education systems, such as teacher training, school design, data collection, etc. (UNESCO, Citation2021). Indeed, as discussed above, current efforts to target such areas are crucial steps towards inclusive education for all students. However, I argue here that the discourse must shift to include higher leverage points; not to pull resources away from current initiatives, but to support them.

This article offers no concrete suggestions on how to change current educational rules, goals, and mindsets. However, acknowledging, exploring, and discussing high leverage points within education systems is a good starting point. There are two promising areas of research that I would like to draw attention to; areas that may perhaps offer more solid frameworks for an exploration of the issues presented here.

Firstly, Green’s (Citation2016) ‘power and systems’ approach to making change happen. Although not specifically centred on education, Green’s work examines the drivers of inequality and possible system-level interventions; crucially, it examines power dynamics and their importance in bringing about change at high leverage points, such as system rules and mindsets (policies, laws, etc). Secondly, Fischer and Riechers (Citation2019) thoughts around leverage point interaction; that is, how different leverage points—system rules, information flows, balancing feedback loops, etc.—affect (and are affected by) one another. An example is league tables that, as discussed above, are information flows that affect system goals (and are affected themselves by mindsets). The concept of leverage point interaction raises the possibility of using levers that can be reached to target those that can’t.

I conclude with a call for further discourse and research into ways to combine Green’s ‘power and systems approach’ with an examination of ‘high leverage points’ within education systems, and how they interact. The latter can identify the points of intervention within complex systems, while the former can be used to devise how such interventions might be structured. The development of a related framework, or Toolkit, could be useful for practitioners and theorists alike. Creation of such a framework could be guided by the work of Gert Biesta, or Matthew Schuelka & Thomas Engsig who write thoughtfully on educational purpose, along with input from international organisations or advocacy groups. This would marry the theoretical contributions to educational purpose and leverage points with the more ‘pragmatic’ approach of development partners. Such a framework would be particularly useful for those working in the development sphere who have access to high-level decision makers. It would allow users to step back and consider the wider system that they are a part of, their role within it, and where best they can target their efforts to ensure that they are impactful, transformative, and sustainable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Ingram

Richard Ingram is a PhD student at the University of Exeter’s Graduate School of Education. He has also worked with UNESCO for several years as a consultant, and is the creator and host of the podcast Goal 4: Education for All.

Notes

1 League tables rank schools in relation to certain metrics – usually on the academic achievement of pupils – and are published online and in print media.

2 Drawing from Meadows, I use ‘mindsets’ here to refer to a belief, or collection of beliefs held by an individual or by a society. I use the term ‘mindsets’ here in place of similar terms, such as ‘ideology’ (apart from when directly quoting others). Preference is given to ‘mindsets’ as the phrase ‘ideology’ indicates very strong feelings (i.e., an idealogue) or convictions. The important thing to note about mindsets is that they are often unstated; they are our basic assumptions about the world around us. Thus, they hugely influence and inform our decisions and prejudices.

3 ‘Paradigm’ is used to refer to a collection of shared mindsets and behaviours that defines a society. One has mindsets, and one occupies a paradigm: we have neoliberal mindsets, and we live in a neoliberal paradigm.

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

- Ahmed, S. (2020). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

- Apple, M. W. (2007). Ideological success, educational failure? On the politics of No Child Left Behind. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487106297844

- Arnold, R. D., & Wade, J. P. (2015). A definition of systems thinking: A systems approach. Procedia Computer Science, 44, 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2015.03.050

- Ball, S. J. (1997). Policy sociology and critical social research: A personal review of recent education policy and policy research. British Educational Research Journal, 23(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192970230302

- Berhanu, G. (2008). Ethnic minority pupils in Swedish schools: Some trends in over-representation of minority pupils in special educational programmes. International Journal of Special Education, 23(3), 17–29.

- Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: On the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

- Biesta, G. (2017). Education, measurement and the professions: Reclaiming a space for democratic professionality in education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1048665

- Bourassa, G. (2021). Neoliberal multiculturalism and productive inclusion: Beyond the politics of fulfillment in education. Journal of Education Policy, 36(2), 253–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1676472

- Brown, W. (2003). Neo-liberalism and the end of liberal democracy. Theory & Event, 7(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2003.0020

- Burgess, S., Greaves, E., & Vignoles, A. (2020). School places: A fair choice. Educational Review.

- Chavanne, D. (2018). Headwinds, tailwinds, and preferences for income redistribution. Social Science Quarterly, 99(3), 851–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12477

- Emeagwali, G. (2011). The neo-liberal agenda and the IMF/World Bank structural adjustment programs with reference to Africa. In Critical perspectives on neoliberal globalization. development and education in Africa and Asia (pp. 1–13). Brill.

- Fischer, J., & Riechers, M. (2019). A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People and Nature, 1(1), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.13

- Global Education Monitoring Report. (2020). Inclusion in education: All means all. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2020/inclusion

- Green, D. (2016). How change happens. Oxford University Press.

- Groce, N. E. (2018). Global disability: An emerging issue. The Lancet. Global Health, 6(7), e724–e725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30265-1

- Haug, P. (2017). Understanding inclusive education: Ideals and reality. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(3), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1224778

- Hedegaard-Soerensen, L., & Grumloese, S. P. (2020). Exclusion: The downside of neoliberal education policy. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(6), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1478002

- Hickel, J. (2021). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. Penguin Random House.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientifi revolutions. The University of Chicago Press, 2, 90.

- Liasidou, A., & Symeou, L. (2018). Neoliberal versus social justice reforms in education policy and practice: Discourses, politics and disability rights in education. Critical Studies in Education, 59(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1186102

- Mac, S. (2022). Neoliberalism and inclusive education: A critical ethnographic case study of inclusive education at an Urban Charter School. Critical Education, 13(2), 1–21.

- Mansell, W. (2016). England schools: 10,000 pupils sidelined due to league-table pressures. The Guardian UK. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/jan/21/england-schools-10000-pupils-sidelined-due-to-league-table-pressures

- Martínez Virto, L., & Rodríguez Fernández, J. R. (2018). Exclusion and neoliberalism in the education system: Socio-educational intervention strategies for an inclusive education system. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 16(2), 135–163.

- McChesney, R. W. (1999). Noam Chomsky and the struggle against neoliberalism. Monthly Review, 50(11), 40. https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-050-11-1999-04_4

- Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points. Places to Intervene in a System, 19.

- Meadows, D. (2001). Dancing with systems. Whole Earth, 106, 58–63.

- Monat, J. P., & Gannon, T. F. (2015). What is systems thinking? A review of selected literature plus recommendations. American Journal of Systems Science, 4(1), 11–26.

- Monbiot, G. (2016). Neoliberalism–the ideology at the root of all our problems. The Guardian, 15(04).

- Nguyen, N. C., & Bosch, O. J. (2013). A systems thinking approach to identify leverage points for sustainability: A case study in the Cat Ba Biosphere Reserve, Vietnam. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 30(2), 104–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2145

- Norwich, B. (2010). Dilemmas of difference, curriculum and disability: International perspectives. Comparative Education, 46(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050061003775330

- OHCHR. (2023). The world is failing 130 million girls denied education: UN experts. United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/world-failing-130-million-girls-denied-education-un-experts#:∼:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20world%20is%20failing%20130,wellbeing%20and%20prosperity%20for%20all.

- Omwami, E., & Rust, V. (2020). Globalization, nationalism, and inclusive education for all: A reflection on the ideological shifts in education reform. In J. Zajda (Ed.), Globalisation, ideology and neo-liberal higher education reforms, 31–46. Springer.

- Pilger, J. (2016). The new rulers of the world. Verso Books.

- Pirsig, R. M. (1999). Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance: An inquiry into values. Random House.

- Potter, S. (2022). It goes without saying: How the neoliberal agenda is endangering inclusive education. FORUM. https://doi.org/10.3898/forum.2022.64.2.08

- Pozo-Armentia, A. D., Reyero, D., & Gil Cantero, F. (2020). The pedagogical limitations of inclusive education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(10), 1064–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1723549

- Raworth, K. (2017). Why it’s time for Doughnut economics. IPPR Progressive Review, 24(3), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/newe.12058

- Rising, J. (2015). Top 500: Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system https://existencia.org/pro/?p=235

- Schuelka, M. J., & Engsig, T. T. (2022). On the question of educational purpose: Complex educational systems analysis for inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(5), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1698062

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Broadway Business.

- Sgourev, S. V., & Althuizen, N. (2017). Is it a masterpiece? Social construction and objective constraint in the evaluation of excellence. Social Psychology Quarterly, 80(4), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272517738092

- Spady, W. G. (1998). Paradigm lost: Reclaiming America’s educational future. ERIC.

- Stroh, D. P. (2015). Systems thinking for social change: A practical guide to solving complex problems, avoiding unintended consequences, and achieving lasting results. Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Toutain, C. (2019). Barriers to accommodations for students with disabilities in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 32(3), 297–310.

- UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for action on special needs education: Adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education; Access and Quality, 7-10 June 1994

- UNESCO. (2019a). Cali commitment to equity and inclusion in education.

- UNESCO. (2019b). Meeting commitments: Are countries on track to achieve SDG 4?. UNESCO Institute for Statistics Paris.

- UNESCO. (2021). Welcoming learners with disabilities in quality learning environments: A tool to support countries in moving towards inclusive education.

- UNHCR. (2023). UNHCR education report 2023 - Unlocking potential: The right to education and opportunity. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/media/unhcr-education-report-2023-unlocking-potential-right-education-and-opportunity

- UNICEF. (2021). FACT SHEET: The world’s nearly 240 million children living with disabilities are being denied basic rights.

- UNICEF. (2022). Let me learn. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/learning-crisis

- UNICEF. (2023). Child Poverty.

- Waitoller, F. R. (2020). Why are we not more inclusive? Examining neoliberal selective inclusionism (Inclusive education: Global issues and controversies (pp. 89–107). Brill.

- World Bank. (2019). The education crisis: Being in school is not the same as learning. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2019/01/22/pass-or-fail-how-can-the-world-do-its-homework