?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper provides a political-economic analysis of policy evaluation. We focus on Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) as a subset of policy evaluations and argue that they are used instrumentally by decision-makers in order to improve perceptions of reforms and help secure policy legacy. We theorize that this ’credibility premium’ is more valuable for incumbents in politically polarized societies, which we empirically examine using two methods. First, we provide a series of vignettes of prominent randomized evaluations embedded by governments in policy roll-outs and a detailed case study of the Liberian government’s decision to commission a third-party RCT evaluation of a proposed primary school privatization reform. Second, we have compiled a unique cross-country panel data set on RCTs in development policy since 1996, with which we demonstrate that RCTs are more likely to occur in polarized societies, and that the effect is amplified by the degree of political competition.

1. Introduction

When are decision-makers more likely to turn to impact evaluation as a form of evidence in international development policy? The puzzle we examine stems from the observation that policy makers rarely have incentives to invest in policy learning despite access to an epistemically and methodologically diverse technology of policy evaluation on the supply side (Majumdar & Mukand, Citation2004). The ‘fourth wave’ rise of RCT experimentation in the field of international development (highlighted by the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics), its popularity among aid donors, and the unprecedented large-scale use in developing countries (Ravallion, Citation2020), complicates this ‘evidence adoption’ puzzle even further. Proponents claim that RCTs provide objective evidence able to bypass ideological debates, reduce policy uncertainty, and equip policy makers with a powerful tool to design interventions for measurable improvements. Critics point out external and internal validity issues, a narrow policy focus, implementation flaws, unresolved ethical dilemmas and a high cost of experimentation (Bédécarrats, Guérin, & Roubaud, Citation2020). Their intrinsic methodological merits are subject to ongoing debate.

As a subset of a much broader evidence menu, we focus on the case of RCTs for several reasons. They have recently gained ‘rhetorical power’ among large donors (Ogden, Citation2018) and ‘persuasion’ abilities in aid recipient contexts (Labrousse, Citation2020). This significant influence in the development community, assertive epistemic claims and communicability to various audiences provide special incentives for strategic use by domestic policy-makers (Bédécarrats et al., Citation2020) - the main object of inquiry in this paper. Second, randomized trials are tractable empirically, as there are worldwide repositories capturing their occurrence. This gives us the opportunity to systematically understand the factors that may incentivize domestic policy-makers to adopt this form of evidence. Our results should however apply to other types of evaluations that are subject to similar incentives.

There are many ways in which the local political environment can affect the likelihood that policy evaluation occurs. The ‘supply side’ of evaluation (international organizations, donors, academics) may also respond to local political conditions.Footnote1 However, our analytical focus in this paper is on the ‘demand side’ of impact evaluation, exploring how the local political environment in recipient countries shapes the incentives of incumbent governments to host such forms of policy evidence. We highlight two factors in particular: the polarization of the polity and the competitiveness of the political system.

Our argument focuses on the communicative use of policy evaluation, and more specifically RCTs, rather than on the intrinsic nature of evidence. We thus expect that decision makers - who are often reluctant to subject the policies they advocate to costly testing and ensuing uncertainty - use impact evaluation in anticipation of a ‘credibility premium’ attached to a policy dimension they advocate. Specifically, we explore the (political) conditions under which the ‘credibility boosting’ benefits of policy evaluation for incumbents outweigh the costs involved with hosting an experiment. This credibility and legitimacy premium is likely to be higher in politically polarized contexts where stakeholders’ preferences are far apart. We focus on how incumbents may use evaluation instrumentally to achieve a policy reform that is consistent with their own preferences and increase the likelihood that it survives political turnover. Our argument emphasizes only the policy makers’ decision to take up costly evaluations and does not attempt to draw any causal link between commissioned evaluation results and the intrinsic quality of the reform. With its emphasis on domestic politics, our findings join broader methodological debates related to the potential ‘political site selection’ bias in the specific case of RCTs (Bédécarrats et al., Citation2020; Corduneanu-Huci, Dorsch, & Maarek, Citation2021; Das, Citation2020; Ogden, Citation2018; Pritchett, Citation2002).

The paper proceeds as follows. We first provide three vignettes motivating our logic and a formal framework to understand the decision of an incumbent government to host or allow policy evaluation. Our theoretical analysis has two sharp hypotheses: first, incumbent governments in more polarized polities are more likely to host evaluations in the form of RCTs and, second, greater political competition increases (decreases) this likelihood in the most (least) polarized polities. We then investigate these hypotheses with a mixed-method empirical strategy. In the third section, we present a case study of policy experimentation taking the form of an RCT within the context of a major and highly contested educational reform in Liberia. The fourth section presents our quantitative empirical results. We study systematically the impact of polarization and political competition on the likelihood of hosting a policy experiment, and focus on RCTs for which data exist systematically in a large-N, cross-country setting.

2. Polarization and credibility-seeking policies

2.1. Policy reforms and the rhetorical power of evidence paradigms

We first motivate our theoretical mechanism with three vignettes that cover the world’s largest RCT evaluations ever commissioned by central governments and embedded in encompassing policy roll-outs. Subsequently, we articulate the logic in a formal model.

The first large scale policy RCT was designed in the United States during the 1970s to evaluate ideologically contested welfare-to-work programs aiming to increase employment and reduce poverty. When researchers advocated randomization, state-level politicians were reluctant to embrace the methodology because of the potential contrast between findings and their own partisan claims. In this highly polarized social policy area where the two major political parties had diametrically opposed preferences, federal bureaucrats opted for an RCT as ‘the only way to get out of the pickle of these dueling unprovable things … and salvage the credibility of the program …’ (Gueron & Rolston, Citation2013, pg. 18).

In international development, a widely cited randomized study adopted in 1997 evaluated for the first time the impact of Progresa, a Mexican conditional cash transfer program that paved the way for the popularity of CCTs worldwide. The RCT took place at a crucial moment of polarized politics accompanying the democratization process in Mexico, a context where large-scale anti-poverty programs traditionally fueled clientelistic linkages and thus contributed to the longevity of the hegemonic incumbent. Its bureaucratic initiators specifically partnered with a US-based research institute to signal to stakeholders the credible, apolitical and technocratic nature of social programs, a key component of President Ernesto Zedillo’s ‘New Federalism’ platform at the time. The RCT’s findings were released and communicated strategically to various stakeholders and to the media during presidential elections in an attempt to persuade opponents, and contributed to Progresa being the first social program to survive presidential turnover in Mexico (Faulkner, Citation2014).

In India, the central government introduced Aadhaar, or biometric identification cards, in 2010 with the intention to reduce corruption in social benefit disbursement. Given its broad coverage of over one billion users, this program has been hailed by some as one of the largest investments in state capacity ever made (Muralidharan, Niehaus, & Sukhtankar, Citation2020). Concomitantly, the policy was highly polarizing from its inception. Critics vocally expressed fears related to exclusion errors, government surveillance, and other negative consequences for the most vulnerable populations. The heated controversy led to decade-long debates among policy-makers, academics, private sector actors, and manifested itself in a series of recent Supreme Court decisions (in 2018 and 2023) on the very constitutionality of the link between identity cards and service delivery. Within this contentious context, the ministerial unit rolling out the program embedded a series of state-level RCTs covering more than 20 million people and conducted by established researchers to evaluate the impact of biometric cards on benefit leakages (Muralidharan, Niehaus, & Sukhtankar, Citation2016). Acknowledging the polarizing pre-electoral environment, the researchers themselves reflected on the strategic role the RCT may play in the sustainability of the project: ‘(…) some of this is political posturing prior to elections. My hope is that our study and the strong benefits we are finding will help create a bipartisan political consensus to proceed with the project. Of course, some tinkering and fine-tuning will be required. But I am optimistic the new government will not shelve the project (…)’ (Muralidharan, Citation2014). The experimenters explicitly emphasized the ideological impartiality of the evaluation and its credibility-seeking function by arguing that despite anecdotes regarding the performance of the program, the ‘(…) RCT results in some states (…) helped to reassure senior policymakers that the programme was beneficial’ (Muralidharan et al., Citation2020). Policy opponents, on the other hand, pointed out the instrumental and selective interpretation of findings by policy-makers given that ’(…) it is quite easy for the evidence to get distorted or embellished in this communication process’ (Drèze & Khera, Citation2020). The RCT study was used in the government’s affidavit to the Supreme Court in an attempt to secure the continuity of the program.

2.2. A Theoretical framework

In this section we present a simple model that analyzes the decision of incumbent governments to run (or allow) a program evaluation with a policy reform and focuses on the role of political competition and polarization. In this framework, the incumbent is assumed not to be purely office-motivated, but also derives utility from having an implemented policy that is closer to her most preferred position, as in the ‘citizen-candidate’ class of models (Besley & Coate, Citation1997; Osborne & Slivinski, Citation1996). We consider policy evaluations to be instruments that may help reforms survive political turnover by changing perceptions of their effectiveness among relevant stakeholders.

There are two periods denoted by and two parties (politicians) denoted by

for the incumbent and the opposition. There are no voters in the model and the incumbent faces an exogenous probability of keeping power,

which is common knowledge and which corresponds to the degree of political competition (Barro, Citation1973). Thus, we interpret higher (lower) values of ζ as lower (higher) degrees of political competition.

The incumbent can decide to run (or allow) an evaluation with the policy reform that can affect the perception of the policy reform’s outcome. The policy implemented can be perceived as producing a good outcome or a bad outcome, indexed by

Without an evaluation, the reform is perceived as good with probability πR and with an evaluation with probability πE (

). Running an evaluation potentially provides information on the reform in a non-partisan way to stakeholders and to policymakers from other parties in the opposition, for instance, which could improve the perception of the reform or at least make it more difficult to oppose the reform for ideological reasons. The evaluation may fail to improve the reform or to convince the stakeholders that the reform’s outcome is good and thus

We assume that running an evaluation has a material cost of ce, which is random and distributed over the support

according to the continuous cumulative distribution function

The distribution of material costs is known before the decision to run an evaluation and is country-specific. We assume that removing a policy that is perceived as producing good outcomes has a cost for politicians as this policy should enjoy a higher support from stakeholders. The cost for the (next) incumbent of removing a policy perceived as bad is CB and CG for a policy perceived as good (with

).

We assume that politicians care about three things. First, she is office-motivated and enjoys an ego rent of being in office, RI. Second, she gets utility from a policy reform that is perceived to produce good outcomes, if she remains in office next period. We normalize the utility from a bad outcome to be zero,

Third, she cares about her political legacy and that her policy survives in period 2 if she is not in office. If the incumbent politician does not remain in office until the second period, she enjoys a rent of RS if the reform survives and if not, she gets 0. We suppose that the rent from a reform that survives the political turnover for an incumbent who does not remain in office depends on the degree of polarization in politics and society, which we denote by θ. We assume that

is strictly increasing in θ. The gain of having its policy maintained (or the loss of having its policy suppressed by the next incumbent) is bigger in a polarized environment as the bliss point of the opponent is further from the incumbent’s bliss point when politics are more polarized. The next politician in office enjoys

if the policy of the previous incumbent remains in place, with

We can write the value function for the incumbent (and the next incumbent at equilibrium) if not running the evaluation:

(1)

(1)

The incumbent is re-elected for a second term with probability ζ and enjoys the rent from being in office the next period. With probability the incumbent will be in the opposition next period. In equilibrium, the next incumbent will not remove the policy previously implemented if it is perceived as good with probability πR, as

and she gets

from being in opposition when the reform survives and an additional

utility if reelected. With probability

the policy is perceived as bad and the next incumbent removes it as

, and she gets a zero payoff from being in opposition.

We can write the value function for the incumbent (and the next incumbent at equilibrium) if running the evaluation:

(2)

(2)

The logic is the same as before except that the incumbent now incurs the cost of running the evaluation and she enjoy the rent if loosing the election with a higher probability since

Comparing Equationequations (1)(1)

(1) and Equation(2)

(2)

(2) , and noting that

there exists a cost

higher than zero such that for

we have

and the politician chooses to run an evaluation. We can derive two main results from this simple illustrative model.

Proposition 1.

Higher polarization increases the probability of an impact evaluation.

Proof.

In Appendix A (available in Supplementary Materials). □

The intuition for Proposition 1 is simple. When polarization increases, the value of running an impact evaluation is higher if the incumbent becomes the next opponent. If the reform is perceived to produce a bad outcome and, accordingly, does not receive much support from the relevant stakeholders, the next incumbent will remove the policy of the previous incumbent and implement its own policy, which is further away in policy space in a more polarized environment. This incentivizes to secure the reform through consensus-seeking evaluation. We can then show our second theoretical result:

Proposition 2.

The impact of political competition on the probability of an evaluation depends on the degree of polarization. Greater political competition increases (decreases) the probability of an evaluation occurring in high (low) polarization environments.

Proof.

In Appendix A. □

The intuition for Proposition 2 is the following. When polarization is low then the reform’s continuity and political legacy is not a big concern for the politician. In such a case, higher political competition lowers the incentive to run an evaluation since the value of the evaluation if the incumbent loses power is low relatively to its value when the incumbent remains in power, but involves current period material costs. On the other hand, when polarization is high, an increase in political competition (a higher probability of losing power) translates into a greater incentive to run an evaluation given the fact that a policy outcome perceived as bad translates into a much lower utility if the incumbent looses power and becomes the new opponent. If the probability of becoming the new opponent is higher (higher political competition), then the incentive to improve the perception of the reform’s outcome to secure the reform is higher in the polarized environment. Note that the magnitude of the impact of political competition and polarization on the probability of an evaluation increases in the effectiveness of the evaluation in improving perceived policy outcomes.

To sum up, the main empirical predictions of the model we can test in the data are: 1) the probability of observing an evaluation increases with the polarization of the polity, all else equal, and 2) the marginal impact of political competition on evaluation depends on the degree of polarization.

3. Case study: RCT politics in Liberia

3.1. Background and timeline

In the wake of a prolonged civil war and Ebola pandemic, public education in Liberia – the fourth poorest and fifth most ethnically fractionalized country in the world – has faced a severe crisis. In 2013, none of the high school graduates passed the university entrance examination. In 2014, net primary enrollment was only 38%, and literacy and numeracy skills ranked extremely low even compared to other Sub-Saharan countries at similar income levels. Aiming to tackle this daunting problem, in 2015 Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf decided to adopt an urgent policy solution. In January 2016, one year before highly competitive national elections, George Werner, her Minister of Education, launched a program aiming to outsource the entire primary and pre-primary public education system to a single private education provider, Bridge International Academies, a Silicon Valley for-profit company.

The initial plan did not entail significant consultation with stakeholders, and triggered unprecedented domestic and international polarization among trade unions, the government, civil society groups, and media outlets. Importantly, in an attempt to persuade antagonistic stakeholders that the reform is likely to produce positive attainment outcomes, the Ministry of Education commissioned last minute a RCT from a reputable team of international researchers (Romero, Sandefur, & Sandholtz, Citation2020). The findings highlighted significant educational gains in the treated schools, but warned policymakers about negative externalities and a vastly heterogeneous performance across providers. Following a competitive election in 2018 leading to the first democratic alternation in Liberian history, the new government, despite initial skepticism and drawing extensively upon the first-year RCT results, decided to maintain the spirit of the program.

3.2. Societal cleavages and policy polarization: the central role of education in the 2017 election

After fifteen years since the civil war, the constitutional mandate of President Johnson Sirleaf was set to expire in January 2018. Despite her international fame, domestic public perceptions of her record in office have been mixed, combining support for a technocratic reform agenda with nepotism and corruption allegations. In 2017, Johnson Sirleaf’s Vice-president, Joseph Boakai became the incumbent candidate and ran against George Weah, the opposition leader. Education, as a marker of societal inequality and cleavages, featured prominently in the electoral campaign as candidates were perceived either ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ education (Sawyer, Citation2008). Unity, Sirleaf Johnson’s political party, cultivated a base revolving around an educated middle class, entrepreneurs and technocrats with a global outlook. The President herself was a Harvard educated economist, had extensive experience in the World Bank as well as the US banking sector, and won 2011 Nobel Peace Prize. The main contestant, George Weah, ran on the ticket of the Congress for Democratic Change (CDC) and received electoral support from indigenous movements fighting to prevent the return of the old elite class. Contrary to Sirleaf Johnson, Weah embodied a ‘rags to riches’ story, a former football star without formal education who became wealthy because of his athletic career. He managed to inspire the poor with a populist agenda that blamed the ‘education’ of political elites as the very root of policy failures in Liberia (Sawyer, Citation2008). Relevant for the high salience of the issue, one of the pro-Weah chants was ‘Degree Holders, You know Book and [yet] we in the mansion’. Attitudes towards education, not only as a public good to be delivered to citizens, but as the core feature of candidate identities became electorally central. It is within this competitive context where the incumbent expected to lose power, that the policy reform took place.

In 2016, the President and the Minister of Education visited some of the schools operated by Bridge International Academies (a Silicon Valley private entity) schools in Uganda and Kenya. Upon return, without significant consultation or competitive procurement bidding, the government contracted Bridge as a sole provider of education in 120 public schools (Cameron, Citation2020). The timing and the rapid introduction of this game-changing reform was largely perceived to be related to the upcoming elections. In the words of an op-ed defending the project, ‘It’s a last-minute maneuver to affect coming elections: True – but hardly unusual. At least a government with a desperate problem is trying something’ (Rosenberg, Citation2016).

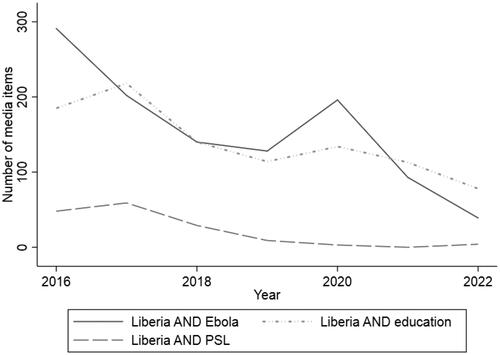

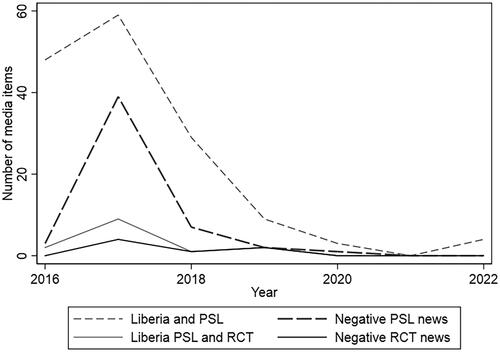

During an electoral year, the debate surrounding the reform intensified. The National Teachers Association of Liberia (NTAL), a politically powerful union, voiced its strong opposition and managed to mobilize important international actors in its defense. Its concerns ranged from the very spirit of the reform, privatizing primary education in one of the world’s poorest countries and the unconventional tablet-centered pedagogy, to concrete stakes for its members such as massive anticipated lay-offs of teachers and students in the privately run schools. Rapidly, the polarization and saliency surrounding the project received unprecedented headlines in domestic and international media outlets (the New York Times, Silicon Valley’s Quartz, the Economist, Liberia’s Daily Observer, Front Page Africa, and others). situates the controversial policy on the general map of Liberia-related news that received substantial media coverage between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2022, based on the results of a content analysis of all major Liberian and international newspapers, magazines, journals, newswires and press releases captured by the NexisUni database. Corroborating its high salience, the PSL reform accounted for a substantial share of all media coverage of education-related issues, which by themselves are comparable in terms of news item frequency to Ebola - a dominant headliner on Liberia. Since the reform was largely funded by international donors, many perceived the high level of polarization to be detrimental for future aid streams.

In this highly polarized environment, in order to appease opposition, the policy-makers altered the initial reform plan in several key respects. As a result, the program, renamed Partnership Schools for Liberia (PSL), restarted with a small-scale pilot of 93 privatized schools run by eight private operators instead of only one. Most importantly for the argument of this paper, George Werner, the Minister of Education at the heart of the controversy, decided to commission an independent RCT to evaluate the impact of privatization on educational attainment, publicly committing to decide whether to scale up or not based on the results of the evaluation.

3.3. Policy evaluations and politics

The RCT was to be conducted by international researchers from the Centre for Global Development (CGD) and Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA). The impact evaluation included all 93 privately run schools and covered 8.6% of the student population. The schools were allocated to treatment and control group by match-pair design. All providers received a subsidy of 50 USD per student. The evaluation intention-to-treat (ITT) design attempted to by-pass potential selection effects by combining random assignment of schools and comparable samples of students (Romero et al., Citation2020). The evaluators chose to test the impact of outsourcing on a variety of outcomes, overall and across private providers: learning gains (English and Math scores); enrollment, attendance and selection; resources (teacher dismissals and performance); household behavior and satisfaction, student fees and attitudes towards learning. The baseline data collection took place in September/October 2016. The end-line surveys were implemented after one year, in May/June 2017, and after three years (March/April 2019) (Romero et al., Citation2020).

The RCT itself received an unprecedented level of attention and media coverage, highlighting the ‘rhetorical power’ and credibility premium that policy-makers attached to its findings in a politically polarized environment (Gueron & Rolston, Citation2013; Ogden, Citation2018). In 2016, the Minister of Education told the New York Times: ‘[…] don’t judge PSL on ideological grounds. Judge us on the data – data on whether PSL schools deliver better learning outcomes for children’ (New York Times, June 14, 2016). In January 2017, Minister Werner published an op-ed justifying the RCT:

Any bold policy reform will always be controversial and will attract scrutiny. This was no exception. 12 months ago, I announced Partnership Schools for Liberia and it quickly became a media sensation, with a flurry of coverage in the Liberian and global media. Unfortunately, at the time, and until now, the facts have rarely been reported correctly and ideology has driven the debate. But with hundreds of thousands of Liberian children enrolled in failing government schools, denied the quality education they deserve, now is not the time to be ideological. Now is the time to be bold, to pilot and experiment and, of course, to rigorously evaluate those pilots before scaling. […] At my request, PSL is being rigorously evaluated by a world class research team to provide an independent measure of the effectiveness, equity and sustainability of PSL. The research team works hand-in-hand with the Ministry of Education so we get the data we need to make sensible policy decisions about the future of PSL (Werner, Citation2017).

There are several empirical clues pointing to the instrumental (as opposed to genuine learning) use of RCT results in this case. First, in line with our communicative use argument, under the pressure of upcoming elections and without waiting for the actual results of the RCT due in June 2017, the Minister of Education announced the scale-up of the pilot to 202 additional schools in the following year (Cameron, Citation2020; Klees, Citation2018). In response, the RCT evaluators released an open letter to the Minister warning stakeholders that any decision to scale-up was not backed by the evidence gathered at the time and reminding the government of the public commitment made to expand the reform only after the results are in Romero et al., April (14, 2017).

Second, the one-year PSL evaluation overall indicated mixed results (Romero, Sandefur, & Sandholtz, Citation2017). Regarding learning gains that took the front stage in the government’s communication strategy, treatment school students clearly outperformed by 0.18 standard deviations (about 60% in test scores in Mathematics and English) compared to control schools. Teachers in treatment schools were also 50% more likely to be in school during random checks and 43% more likely to be engaged in educational tasks during class time. The study, however, noted significant heterogeneity among private providers. The highest performing providers generated score increases of over 0.36 standard deviations, while the lowest-performing providers had no impact (Romero et al., Citation2017). Problematically, the company at the core of the controversy generated negative externalities by pushing excess pupils and teachers out of treatment schools. The evaluators clearly stated the danger of focusing exclusively and unidimensionally on learning gains in such a complex policy package whereby ‘(…) test score gains and expenditures fail to tell the entire story of the consequences of this public-private partnership’ and ‘(…) some of the providers engaged in the worst behavior were considered some of the most promising’ (Romero et al., Citation2020, pg. 366-367). The highly publicized RCT report formulated policy recommendations revolving around the transparent selection of providers, stricter contracting and monitoring requirements to avoid negative effects, and noted unsustainably high costs in some of the privately operating schools (Romero et al., Citation2017).

3.4. The RCT and the post-election policy legacy

After a competitive first round held in October 2017, Weah won the run-off election with a 23% vote margin in December, while CDC and Unity obtained a roughly similar number of seats in the legislature (1% margin of votes). The position of out-going President Johnson Sirleaf has been surprisingly ambiguous, and her own post-electoral political fate turned inauspicious. Following allegations that Johnson Sirleaf secretly facilitated George Weah’s victory instead of supporting her own Vice President, Unity, her party, expelled her in 2018 (Spatz & Thaler, Citation2018).

Given this tense political climate following the electoral loss of the educational reform champions, it is remarkable that the policy (since 2018 rebranded as Liberia Educational Advancement Program (LEAP)) survived the political transition. One newspaper article noted: ‘Uniquely, LEAP has thrived under two different administrations […] Strong political leadership and a clear focus on improving schools for Liberia’s children trumped the struggles signature policies often face with regime change’ (Front Page Africa, Citation2019). In fact, in his first State of the Nation address in 2018, President Weah explicitly referred to education as the first pillar and priority of his mandate. In an op-ed to New York Times (Weah, Citation2019), the Liberian president wrote: ‘We are determined to move forward. The core of my efforts will be helping the worst off in Liberia. Education will play a central role in pushing the economy forward. We are rebooting our educational system so that everyone can have access to quality education’.

The new Minister of Education, Ansu D. Sonii, appointed in February 2018, was initially skeptical of maintaining the reform. His team embarked on a ‘County Tour’ visit of the privately run schools and drew heavily upon the RCT results. A pro-government source noted:

The transition to LEAP is the result of a thorough study – by the Ministry of Education – of the education landscape in Liberia; exploring the situation in many schools across Liberia’s Counties. Rightly, our new administration wanted to review the program and its impact to see whether it could – and indeed should – commit to its future. Amidst their review, they considered the highly anticipated independent evaluation that was conducted by the Center for Global Development and Innovations for Poverty Action last year. The study was greeted with much excitement and pride when it revealed learning had increased by 60% inside Partnership schools (with Bridge students learning twice as much as their peers). It was likely these learning gains – amidst other considerations – that have been instrumental in the decision (Wleh, Citation2018).

4. Quantitative empirical investigation

4.1. Data and methodology

We have conducted a cross-country panel regression analysis in order to establish how the likelihood of having a RCT can be explained by our two primary variables of interest: the degree of polarization (θ in the model) and the level of political competition (ζ in the model).

Data for our main dependent variable, the incidence of a RCT taking place in county i during year t, was kindly provided by The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie), an initiative of leading international donors to systematically store and summarize all published impact evaluations in international development in their Development Evidence Portal.

We consider both the raw count data (the number of RCTs in a country year) as well as a binary indicator variable that takes value one if there was at least one RCT in a country year and zero otherwise. In our baseline specification, we have an unbalanced panel of 157 countries from 1996 – 2014, during which time the unconditional probability of at least one RCT in any given year was around 19 per cent. In Appendix B (available in Supplementary Materials), shows a heat map of the developing countries that have hosted the most RCTs according according to the 3ie repository. In our baseline analysis, we exclude the United States, which is by far the largest space for RCT experiments. In Appendix B, we demonstrate that the results are robust if we include the United States, and also and if we exclude all of the advanced industrialized democracies.

The 3ie data does not, unfortunately, have information about the identity of experimental partners, which is important for the ‘demand-side’ focus of our theoretical framework. Thus, we have additionally employed the original data set from Corduneanu-Huci et al. (Citation2021) on RCTs conducted by J-PAL (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab) from 1995 – 2014. Corduneanu-Huci et al. (Citation2021) have coded J-PAL RCTs with a wide variety of characteristics, including whether or not an RCT was ‘state-sponsored’, which we argue isolates RCT incidence that was driven by the demand side.

As a proxy for the degree of polarization in society, we have used the index of ethnic fractionalization provided by Alesina, Devleeschauwer, Easterly, Kurlat, and Wacziarg (Citation2003), which measures the probability that two randomly selected individuals will belong to different ethnic groups, combining racial and linguistic characteristics.Footnote2 In our robustness analysis, we also consider a variety of other non-ethnic proxies for societal polarization.Footnote3 One drawback of the polarization proxies is that they are time invariant, but we are not aware of better proxies for polarization of policy preferences that covers the full range of developing countries.

In the model, we referred to political competition as the probability that the incumbent government survives the next election. To proxy for this variable, we use data from the Database of Political Institutions (Cruz, Keefer, & Scartascini, Citation2016) to calculate ruling margins of incumbent governments, operationalized as the margin of vote share for the winning political party over the second place party. We interpret a lower margin of votes to correspond to more competitive elections and a lower probability that the incumbent party will survive the next election. We have also considered several alternative proxies in our robustness analysis, such as margins of parliamentary seats and the the strength of the opposition parties, for example.

Finally, all regressions control for macroeconomic cycles (the log of per capita Gross Domestic Product in constant 2010 US dollars) as well as the log of population size, both taken from the World Development Indicators. Appendix provides summary statistics for data used in the analysis.

4.2. Econometric specifications

Formally, we estimate the following pooled cross-section regression:

(3)

(3)

where

is a measure of political competition,

is a proxy for political polarization, X is a vector of control variables that includes the log of per capita income and the log of population in the baseline specifications, and the δt’s denote a full set of period dummies that capture common shocks and common time trends. We include the lagged dependent binary variable as a reduced form control for supply-side effects (research networks, experimental infrastructure, etc) and to isolate new experiment starts. Since the ethnic fractionalization index that we use to proxy for political polarization is time-invariant, we cannot include a country fixed effect when estimating Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) . The error term

captures all other factors not correlated with our controls which may also explain the occurrence of RCTs, with

for all i and t. All estimations cluster standard errors at the country level.

We next examine the testable hypothesis concerning the effect of political competition conditional on the degree of polarization, employing a linear multiplicative specification:

(4)

(4)

where

is the variable of interest. As the interaction term is time-varying, we now introduce a country fixed effect into the estimation. In Equationequation (4)

(4)

(4) , the λi’s denote a full set of country dummies that control for any time-invariant country characteristics. From Equationequation (4)

(4)

(4) , we can see that the impact of political competition depends on the degree of polarization in the society.

(5)

(5)

Theoretically, we expect that competition leads to more RCTs when polarization is high and fewer RCTs when polarization is low. Thus, we expect that and

4.3. Estimation results

The first column of estimates Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) using a linear probability model, and demonstrates that greater political polarization is estimated to have a positive and statistically significant impact on the likelihood of hosting at least one RCT, verifying Proposition 1. Greater political competition (lower vote share margins) is estimated to have a statistically insignificant effect on the probability of hosting a RCT when looking at the 3ie data. The insignificant result with the political competition proxy is perhaps not surprising. Given our theoretical hypotheses we may expect that the positive impact of political competition in highly polarized societies cancels out with the negative impact of competition in societies where polarization is low. When using the J-PAL data, the effect of political competition is statistically significantly positive.

Table 1. Experiments and the government’s vote share margin

Column 2 of estimates the multiplicative specification of Equationequation (4)(4)

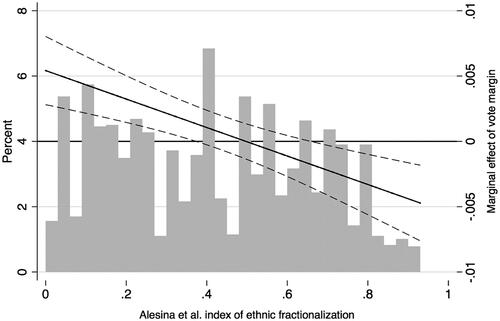

(4) and investigates the extent to which the effect of political competition is stronger in countries where the polity is more polarized. For a society that is perfectly ethnically homogenous (Polar = 0), the wider vote margins are estimated to be positive, but the effect diminishes as ethnic fractionalization increases, turning negative at some critical value of fractionalization. In support of hypothesis 2, greater political competition increases the likelihood that an experiment is held (above the threshold fractionalization value) and the marginal effect is greater in more polarized societies. plots the marginal effect of an increase in the vote margin (a decrease in political competition) as a function of the degree of ethnic fractionalization on the probability of running an experiment as estimated in column 2.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of an increase in the margin of votes on the probability of having an experiment as a function of ethnic fractionalization.

To ease the interpretation of the heterogeneous marginal effect of political competition, splits the sample at the median value for polarization. As we are not using polarization as a regressor, these specifications include country fixed effects. Here it is clear that political competition increases the likelihood of an RCT in highly polarized polities, but decreases the likelihood in polities that are not very polarized. The results are economically significant. A one standard deviation increase in political competition increases the probability of observing an experiment in the high polarization sub-sample by 5.4 percentage points, which is about 29 percent of the unconditional mean probability.Footnote4

Table 2. Experiments and the government’s vote share margin

Columns 3–6 of employ the J-PAL data. This data allows us to isolate the ‘demand-side’ dynamics that are at the center of our theoretical framework. By investigating RCTs conducted by the same institution, we are able to control for how the ‘supply-side’ may be influenced by our variables of interest. Columns 3 and 4 consider all RCTs performed by J-PAL and demonstrates that their incidence is similarly determined by political competition and political polarization. Columns 5 and 6 consider the subset of J-PAL RCTs that were state-sponsored. First of all, by comparing the unconditional means of the the two J-PAL DVs, we see that roughly half of the country/years in which J-PAL RCTs occurred were state-sponsored, indicating that the ‘demand-side’ of RCTs is non-negligible. Second, we see that political competition and polarization remain statistically significant explanators for the incidence of state-sponsored RCTs. The J-PAL data allows us to isolate RCTs that are demand-driven and also verify our main result with a second data source.

4.4. Robustness of results

In Appendix B of the Supplementary Materials we also consider several robustness tests: (i) alternative samples and specifications of baseline results from , (ii) additional time-varying controls, (iii) alternative measures of polarization and political competition, and (iv) further results with the J-PAL data on RCT incidence.

First, in Table A2 we provide more results using the 3ie data, including logit estimators for the baseline binary DV and models that use the raw count RCT data from 3ie as DV. Next, we have run a series of robustness tests where we reproduce with some modified specifications. In Table A3, we drop the lagged dependent variable from the specification. Table A4 estimates the regressions over the entire sample (i.e. including the United States). Table A5 estimates the regressions over a limited sample that drops all the advanced industrialized democratic countries. Table A6 controls for the democratic quality of political institutions using the Polyarchy index from the V-Dem Project and for official development assistance using data from the OECD.

Second, we consider alternative measures of polarization and political competition. Table A7 employs additional measures of ethnic fractionalization, as well as the size of the largest minority group and the size of the largest plurality group (Fearon, Citation2003). To tap into ideological (non-ethnic) cleavages, we also consider a V-DEM measure of societal polarization, which asks country experts ‘How would you characterize the differences of opinions on major political issues in this society?’ (Coppedge et al., Citation2017). We have also considered alternative measures of political competition. Table A8 reproduces Table A2 using the margin of parliamentary seats measure of political competition. The baseline specifications from columns 1 and 2 of are reproduced in Table A9 with further alternative measures of competition, namely the parliamentary seat share of the winning party, the vote share of the government, the share of parliamentary seats that are held by opposition parties, and the index of oppositional fractionalization.

Finally, Table A10 presents additional results using the J-PAL RCT data. In , we showed results for DV’s that considered all RCTs and RCTs that were state-sponsored. In Table A10, we additionally present results for RCTs that were not state-sponsored and for RCTs that explicitly evaluated a status-quo government policy.

5. Conclusion

Under which conditions are incumbent governments likely to evaluate public policies? Focusing on RCTs, we find that political polarization and its interaction with political competition, correlate significantly with the likelihood that a country hosts at least one evaluation in a given year. These were also key elements that we explored in our case study of Liberia’s decision to sponsor an RCT during a major reform to its public education system, as well as in other vignettes capturing the world’s largest evaluations embedded in comprehensive development policy packages. The desire of incumbent politicians to persuade opponents and potentially ‘lock in’ policy reforms across administrations should they lose the next election is strongest in polarized and competitive environments. The interaction of these two political factors increases the incidence of RCTs in a country, a finding which puts some micro-foundation on the demand side of the ‘political site selection bias’. Polarized political contexts are often associated with sub-optimal political and economic outcomes. However, our results show that polarized societies may counter-intuitively provide fertile ground for credibility-seeking experimentation that more stable political contexts might not.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (454 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from seminar participants at the the Université Paris - Dauphine (DIAL), Université Libre de Bruxelles, the Université Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne, the Università di Roma La Sapienza, Higher School of Economics (St. Petersburg), and the Central European University (Budapest). In particular, the authors thank Mariyana Angelova, Ágnes Batory, Caitlin Brown, Gabriel Cepaluni, Quentin David, Amanda Driscoll, Andreas Madestam, Mikael Melki, Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Edward Miguel, Arieda Muco, and Anand Murugesan for comments and conversations that have improved this paper. Part of this research was carried out while Dorsch was visiting the Université Paris-Panthéon Assas and he thanks them for their hospitality and financial support. The authors thank the 3ie for providing us with the meta data from their online repository and for responding to our queries. Supplementary Materials can be found on the Corresponding Author’s personal website: https://sites.google.com/view/dorsch/research?authuser=0

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MTD, upon reasonable request.

Notes

1 See Corduneanu-Huci et al. (Citation2021) for an overview of how the supply side of RCTs may be affected by the political environment in the hosting country. They also show that a large share of RCTs are executed with governmental partners. See also the meta-study of Corduneanu-Huci, Dorsch, and Maarek (Citation2022).

2 Technically, the measure is one minus the Herfindahl index of ethnic concentration. For country j, where sij is the share of ethnic group i in the population of country j.

3 See Bhavnani and Miodownik (Citation2009); Chandra (Citation2005), and Mozaffar, Scarritt, and Galaich (Citation2003) for examples of papers that use ethnic fractionalization as a proxy for political polarization, especially in developing economies.

4 The standard deviation of the vote share variable is 27.01, multiplied by the coefficient -0.002 in the high polarization sub-sample gives -0.054. The unconditional mean of the dependent variable is 0.188.

References

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R., & Easterly, W. (1999). Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(4), 1243–1284. doi:10.1162/003355399556269

- Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 155– 194. doi:10.1023/A:1024471506938

- Barro, R. J. (1973). The control of politicians: An economic model. Public Choice, 14-14(1), 19–42. doi:10.1007/BF01718440

- Bédécarrats, F., Guérin, I., & Roubaud, F. (2020). Randomized control trials in the field of development: A critical perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Besley, T., & Coate, S. (1997). An economic model of representative democracy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 85–114. doi:10.1162/003355397555136

- Bhavnani, R., & Miodownik, D. (2009). Ethnic polarization, ethnic salience, and civil war. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53(1), 30–49. doi:10.1177/0022002708325945

- Cameron, E. (2020). The sweeping incrementalism of Partnership Schools for Liberia. Journal of Education Policy, 35(6), 856–870. doi:10.1080/02680939.2019.1670866

- Chandra, K. (2005). Ethnic parties and democratic stability. Perspectives on Politics, 3(02), 235–252. doi:10.1017/S1537592705050188

- Coppedge M., Gerring J., Lindberg S. I., Skaaning S. E., Teorell J., Altman D., Hicken A., et al. (2017). V-Dem Dataset v7.

- Corduneanu-Huci, C., Dorsch, M. T., & Maarek, P. (2021). The politics of experimentation: Political competition and randomized controlled trials. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(1), 1–21. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2020.09.002

- Corduneanu-Huci, C., Dorsch, M. T., & Maarek, P. (2022). What, where, who, and why? An empirical investigation of positionality in political science field experiments. PS: Political Science & Politics, 55(4), 741–748. doi:10.1017/S104909652200066X

- Cruz, C., Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2016). Database of political institutions codebook, 2015 update (dpi2015) (pp. 165–176). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

- Das, S. (2020). (Don’t) leave politics out of it: Reflections on public policies, experiments, and interventions. World Development, 127, 104792. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104792

- Drèze, J. R., & Khera, A. S. (2020). Balancing corruption and exclusion: A rejoinder. Ideas for India.

- Edwards, S. (2018). What next for Liberia’s controversial education experiment? Devex.

- Faulkner, W. N. (2014). A critical analysis of a randomized controlled trial evaluation in Mexico: Norm, mistake or exemplar? Evaluation, 20(2), 230–243. doi:10.1177/1356389014528602

- Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222. doi:10.1023/A:1024419522867

- Front Page Africa. (2019). Liberia: Independent RCT results show LEAP equates to more than additional year of learning. Front Page Africa.

- Gueron, J. M., & Rolston, H. (2013). Fighting for Reliable Evidence. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Hollweg, C. H., Sáez, S., Aguiar, A., Walmsley, T., Narayanan, G.,B., Aguiar, A., … Mattoo, A., et al. (2019). World Development Indicators (database). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Klees, S. J. (2018). Liberia’s experiment with privatising education: A critical analysis of the RCT study. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 48(3), 471–482. doi:10.1080/03057925.2018.1447061

- Labrousse, A. (2020). Chapter 8: The rhetorical superiority of poor economics. In F. Bédécarrats, I. Guérin, and F. Roubaud (Eds.), Randomized control trials in the field of development: A critical perspective (pp. 227–255).Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Majumdar, S., & Mukand, S. W. (2004). Policy gambles. American Economic Review, 94(4), 1207–1222. doi:10.1257/0002828042002624

- Mozaffar, S., Scarritt, J. R., & Galaich, G. (2003). Electoral institutions, ethnopolitical cleavages, and party systems in Africa’s emerging democracies. American Political Science Review, 97(03), 379–390. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000753

- Muralidharan, K. (2014). Political pressure halted direct benefits transfer for LPG. Business Standard.

- Muralidharan, K., Niehaus, P., & Sukhtankar, S. (2016). Building state capacity: Evidence from biometric smartcards in India. American Economic Review, 106(10), 2895–2929. doi:10.1257/aer.20141346

- Muralidharan, K., Niehaus, P., & Sukhtankar, S. (2020). Balancing corruption and exclusion: Incorporating Aadhaar into PDS. Ideas for India.

- Ogden, T. (2018). Experimental Conversations: Perspectives on Randomized Trials in Development Economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Osborne, M. J., & Slivinski, A. (1996). A model of political competition with citizen-candidates. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(1), 65–96. doi:10.2307/2946658

- Pritchett, L. (2002). It pays to be ignorant: A simple political economy of rigorous program evaluation. The Journal of Policy Reform, 5(4), 251–269. doi:10.1080/1384128032000096832

- Ravallion, M. (2020). Chapter 1: Should the randomistas (continue to) rule?. In F. Bédécarrats, I. Guérin, and F. Roubaud (Eds.), Randomized control trials in the field of development: A critical perspective (pp. 47–78). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Romero, M., Sandefur, J., & Sandholtz, W. (2017). Can outsourcing improve Liberia’s Schools? Preliminary results from year one of a three-year randomized evaluation of Partnership Schools for Liberia. Center for Global Development Working Paper.

- Romero, M., Sandefur, J., & Sandholtz, W. A. (2020). Outsourcing education: Experimental evidence from Liberia. American Economic Review, 110(2), 364–400. doi:10.1257/aer.20181478

- Rosenberg, T. (2016). Liberia, desperate to educate, turns to charter schools. The New York Times.

- Sawyer, A. (2008). Emerging patterns in Liberia’s post-conflict politics: Observations from the 2005 elections. African Affairs, 107(427), 177–199. doi:10.1093/afraf/adm090

- Spatz, B. J., & Thaler, K. M. (2018). Has Liberia turned a corner? Journal of Democracy, 29(3), 156–170. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0052

- Weah, G. M. (2019). George Weah: Don’t forget about Liberia. The New York Times.

- Werner, G. K. (2017). Liberia has to work with international private school companies if we want to protect our children’s future. Quartz.

- Wleh, M. (2018). PSL to LEAP, government commits to the continuation of its flagship Education Public Private Partnership in Liberia. Medium.

Appendix. Summary statistics for the cross-country panel