ABSTRACT

Although the quantity of pornography use (QPU, i.e., frequency/time spent on pornography use) has been positively associated with the severity of pornography use (i.e., problematic pornography use, PPU), the magnitudes of relationships have varied across studies. This meta-analysis aimed to assess the overall relationships and identify potential moderating variables to explain the variation in these associations between QPU and PPU. We performed a literature search for all published and unpublished studies from 1995 to 2020 in major online scientific databases up until December 2020. Sixty-one studies were identified with 82 independent samples involving 74,880 participants. Results indicated that there was a positive, moderate relationship between QPU and PPU (r = 0.34, p < .001). The strength of relationship significantly varied across measures of PPU based on different theoretical frameworks, indicators of QPU, and sexual cultural contexts (conservative vs. permissive sexual values). Frequency was a more robust quantitative indicator of PPU than time spent on pornography use. In conservative countries, QPU showed more robust association with self-perceived PPU. Future studies are encouraged to select the measurement of PPU according to research aims and use multi-item measures with demonstrated content validity to assess pornography use. Cross-cultural (conservative/permissive) comparisons also warrant further research.

Over the past two decades, a revolution in information and communication technology has altered sexual behaviors, including pornography use. The conceptual meaning of “pornography use” is broad, as there are several different ways that one can define pornography and consider its use (Busby et al., Citation2020; Kohut et al., Citation2020). Recently, the concept of pornography use is suggested to be defined as “a common but stigmatized behavior, in which one or more people intentionally expose themselves to representations of nudity which may or may not include depictions of sexual behavior, or who seek out, create, modify, exchange, or store such materials. Pornography use can evoke immediate sexual and affective responses, and may contribute to more lasting cognitive, affective, and behavioral changes” (Kohut et al., Citation2020, p. 12).

Two major aspects of pornography use including the quantity and quality/severity of use are present in the literature when examining pornography use (Gola et al., Citation2016). The frequency and amount of time spent using pornography are most often considered as the quantity of pornography use (QPU) (Kohut et al., Citation2020). Yet, it needs to be noted that pornography use is not necessarily associated with significant impairments in different domains of functioning. However, pornography use may become problematic (Blais-Lecours et al., Citation2016; Engel et al., Citation2019; Harper & Hodgins, Citation2016). The quality/severity of pornography use (PPU) usually represents the extent of pornography negatively impacting people’s lives and dominating their thinking, feelings, and behaviors (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Griffiths et al., Citation2021; Chen, Jiang et al., Citation2021). Thus, most researchers consider PPU as persistent, repetitive engagement in pornography use that results in impairment in one’s life in addition to failed attempts to reduce or stop such behaviors (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Demetrovics et al., Citation2021; Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018; Cooper et al., Citation2004; Efrati & Gola, Citation2018; Kraus, Martino et al., Citation2016; Young et al., Citation2000). Quantity of pornography (QPU) was identified as a peripheral symptom (i.e., symptoms that might not belong to the core symptoms of problematic behaviors and might be present in the case of non-problematic, highly engaged users) in PPU (Bőthe, Lonza et al., Citation2020), and it may not be a sufficient indicator of PPU (Bőthe, Lonza et al., Citation2020; Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2020; Vaillancourt-Morel et al., Citation2017). Yet, it can reflect the degree of PPU to some extent (Chen, Ding et al., Citation2018), as previous studies have found that QPU has been positively associated with PPU. However, the magnitudes of these relationships have varied across studies.

Cross-sectional studies have found weak-to-large relationships between frequencies or usage times of pornography use and PPU in undergraduate or adult samples (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Chen, Ding et al., Citation2018; Fernandez et al., Citation2017; Gola et al., Citation2016; Grubbs, Exline et al., Citation2015; Grubbs et al., Citation2017; Grubbs & Gola, Citation2019; Grubbs, Kraus et al., Citation2019; Grubbs, Wilt, Exline & Pargament, Citation2018; Volk et al., Citation2016; Wéry et al., Citation2016). Recent longitudinal studies have investigated these relationships and found that QPU demonstrated small correlations with self-perceived PPU (Grubbs & Gola, Citation2019; Grubbs, Stauner et al., Citation2015; Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, Pargament et al., Citation2018). These findings to date indicate that complex associations might exist between QPU and PPU, suggesting a need for a more comprehensive understanding. Further, identification and analysis of the moderators from a sufficient number of studies can add valuable knowledge to our understanding of how the links between QPU and PPU vary by study characteristics; thus, the present meta-analysis might help identify potential knowledge gaps in the literature and areas to target in future research.

If we wish to better understand the associations between QPU and PPU, both measurement characteristics (QPU and PPU), and individual characteristics should be considered as potential moderators. For instance, QPU assessed with a single item (Kohut & Stulhofer, Citation2018; Rousseau et al., Citation2021) or multiple items (Hatch et al., Citation2020; Leonhardt et al., Citation2021) and PPU measured by scales based on different theoretical frameworks (Chen & Jiang, Citation2020; Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021) may have an effect on the results. Individual characteristics may moderate these associations as well. For example, gender (Pekal et al., Citation2018; Weinstein, Zolek et al., Citation2015), sexual cultural context (Chen, Luo et al., Citation2021; Griffiths, Citation2012; Kraus & Sweeney, Citation2019; Vaillancourt-Morel & Bergeron, Citation2019), sexual orientation (Brand, Brand, Antons et al., Citation2019; Duggan & McCreary, Citation2004; Træen & Daneback, Citation2013) and treatment-seeking vs. community groups (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Demetrovics et al., Citation2021; Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Klucken et al., Citation2016; Lewczuk et al., Citation2017; Voon et al., Citation2014) may have a direct or interaction effect on QPU or PPU.

Literature Review and Potential Moderators

Measurement Characteristics

Assessments of PPU based on different theoretical frameworks. Currently, there is no consensus regarding the conceptualization and diagnosis of PPU (Grubbs et al., Citation2020). Some researchers have considered conceptualization of PPU as an impulse control or compulsivity-related behavior problem (Kuhn & Gallinat, Citation2014; Meerkerk et al., Citation2009; Noor et al., Citation2014), or a potentially addictive behavior (Kraus, Voon et al., Citation2016). However, in some researchers’ opinion, PPU is not yet recognized as a psychiatric disorder because PPU may not necessarily be excessive, addictive, or compulsive (Vaillancourt-Morel & Bergeron, Citation2019), and there are individuals who experience self-perceived PPU due to moral incongruence (Grubbs, Perry et al., Citation2019).

Impaired control (i.e., unsuccessful attempts to reduce or stop a given behavior and difficulties in controlling related urges) is an important feature of impulse control, compulsivity-related, and addictive behaviors as well (Fineberg et al., Citation2014). However, important differences can be observed regarding the nature of impaired control in the different disorders. While impaired control may appear in relation to risk-seeking and risk-taking in the case of impulse control disorders, impaired control is associated with repetitive engagement in behaviors in a habitual manner according to rigid rules to avoid harm in compulsive disorders. In the case of addiction models, both impulsivity and compulsivity-related impaired control may be present (Brand, Wegmann et al., Citation2019; Brand et al., Citation2016; Fineberg et al., Citation2014). Moreover, impaired control may also be an essential criterion to distinguish between individuals with subjective, self-perceived PPU and dysregulated PPU (Chen, Jiang et al., Citation2021). Lastly, addiction models may assess tolerance and withdrawal, two features of addictions (Griffiths, Citation2005), that are pivotal characteristics distinguishing between addictive disorders and obsessive-compulsive and impulse control disorders (Reid, Citation2016). In sum, scales using different theoretical frameworks to assess PPU may focus on different elements or characteristics of impaired control in PPU and may include different symptoms (e.g., tolerance). Therefore, considering the potential role of using scales developed on the basis of different theoretical frameworks is crucial.

Corresponding with the debate on the conceptualization of PPU, over 20 psychometric instruments have been developed to assess various conceptualizations and aspects of PPU (Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021; Karila et al., Citation2014). Associations between QPU and PPU have varied considerably when different PPU measures have been used. Some scales assessing PPU arguably based on obsessive-compulsive frameworks have demonstrated moderate associations with QPU (e.g., Brief Pornography Screen; Sexual Compulsivity Scale) (Lewczuk et al., Citation2020; Wetterneck et al., Citation2012), while scales developed on addiction models (e.g., Griffiths, Citation2005) showed small-to-large associations between QPU and PPU [e.g., Compulsive Internet Use Scale adapted to sexual explicit materials (CIUS-adapted sexual explicit materials) (Brahim et al., Citation2019), and Problematic Pornography Use Scale (PPUS) (Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018; Kor et al., Citation2014]. However, some researchers developed scales to underscore individuals’ subjectively self-perceived addictions [i.e., the Cyber Pornography Use Inventory, (Grubbs et al., Citation2010; Grubbs, Volk et al., Citation2015)], and demonstrated moderate associations between the QPU and PPU. These findings suggest that differences in measurements of PPU may be an important variable explaining variability of strengths in associations between QPU and PPU.

Measurement of QPU. Measures of QPU have primarily included frequency and usage time of pornography use during a given period of time (e.g., past week). Previous studies have suggested that important differences in associations may be present when these two measures of QPU are assessed (Chen, Ding et al., Citation2018; Fernandez et al., Citation2017). Based on prior studies, PPU may be weakly related to the time spent viewing pornography per occasion, while it might have a stronger association with the frequency of use (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Chen & Jiang, Citation2020; Grubbs, Kraus et al., Citation2019; Rimington, Citation2008). However, other studies reported that usage time had a stronger association with PPU than frequency of use (Antons et al., Citation2019). To date, no solid conclusions may be drawn from previous studies whether the frequency of pornography use or the usage time of pornography has a stronger association with PPU.

In reviewing the nature of the QPU scales, most researchers have used a single general question to ask participants to estimate their average QPU (Blais-Lecours et al., Citation2016; Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2020; Bradley et al., Citation2016; Fernandez et al., Citation2017; Wetterneck et al., Citation2012; Wilt et al., Citation2016), while few studies have used self-compiled multi-item assessments (Bőthe, Bartók et al., Citation2018; Harper & Hodgins, Citation2016; Wéry et al., Citation2016) or validated scales (Brahim et al., Citation2019; Chen & Jiang, Citation2020; Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018) such as the Online Sexual Activities questionnaire [OSAs, including a five-item questionnaire for measuring the viewing sexual explicit materials, (L. Zheng & Zheng, Citation2014)]. Whether these two measurement methods have an impact on the strengths of the associations between QPU and PPU has remained unclear and will be examined in the current study.

Sample Characteristics

Gender. Considerable differences may exist in the relationships between QPU and PPU in men and women. Compared to women, men typically consume more pornography as measured by usage time and frequency (Hald, Citation2006; Martyniuk et al., Citation2016; Morgan, Citation2011), and men on average experience higher levels of PPU than women (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Grubbs, Kraus et al., Citation2019). Concerning associations between QPU and PPU (Gola et al., Citation2016; Lewczuk et al., Citation2017), moderate-to-strong relationships were reported between usage time and self-perceived PPU among women (Baranowski et al., Citation2019; Laier et al., Citation2014), while weak-to-strong correlations were reported among men (Antons et al., Citation2019; Laier et al., Citation2015; Wéry et al., Citation2016). Moreover, previous research has demonstrated that the difference in pornography use is one of the greatest differences in sexual behavior between men and women (Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010). However, questions on whether the QPU mirror the severity of pornography use to the same extent between genders have not been explored yet.

Cultural context toward sexual attitudes (conservative/ permissive). The sociocultural context may play an important role in influencing people’s attitudes toward sexual behaviors (Griffiths, Citation2012; Meston et al., Citation1996) and females’ sexual expression (Guo, Citation2019; Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010). Furthermore, cultural characteristics may influence negative attitudes toward pornography use (Vaillancourt-Morel & Bergeron, Citation2019), and some have proposed that conservative sexual cultures may influence self-perception of PPU as well (Grubbs, Wilt, Exline & Pargament, Citation2018). Individuals in sexually conservative cultures [e.g., traditional Asian cultures that stress sexual conservatism (Kim, Citation2009)] may feel more conflict and negative emotions about their use given that it may be in opposition to their sexual moral values, and may be more likely to label themselves as being addicted to pornography. For example, associations between QPU and PPU were stronger in a Chinese sample, compared to a US sample using the same PPU scale (r = 0.60 vs 0.39, respectively) (Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018; Shirk et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, although conservative cultures stipulate sexual restriction for both men and women, female sexuality is typically more restricted, especially for girls and unmarried women (Browning et al., Citation2006; Kim, Citation2009; Okazaki, Citation2002). Therefore, there may be interactions between gender and sexual culture context. For example, while QPU may have a significant impact on women’s PPU levels in more conservative cultures, men’s use might not be as limited by cultural expectations and thus they may not perceive their use as problematic. However, whether the associations between QPU and PPU vary across different sexual culture contexts, and whether there is an interaction between gender and sexual cultural context, have not been examined yet.

Sexual orientation. As a core personal characteristic relevant to sexual behaviors, individuals’ sexual orientation may be considered as a potential variable when examining associations between QPU and PPU (Brand, Brand, Antons et al., Citation2019). Sexual minority men or women typically use more pornography than their heterosexual counterparts (Duggan & McCreary, Citation2004; Træen & Daneback, Citation2013; Træen et al., Citation2006). Sexual minority individuals may also report higher levels of sexual compulsivity compared to heterosexual individuals (Bőthe, Bartók et al., Citation2018; Cooper et al., Citation2000; Weinstein, Katz et al., Citation2015). A possible explanation may be that sexual minorities may experience more negative effects (such as anxiety, depression, anger or stress) in relation to their sexual orientation (Parsons et al., Citation2008), and online pornography, given its accessibility, affordability and perceived anonymity (Cooper, Citation1998), may be a commonly used coping strategy to reduce such unwanted feelings (Bőthe, Bartók et al., Citation2018; Parsons et al., Citation2008).

Community and treatment-seeking participants. Although multiple scales exist for assessing PPU, primarily nonclinical samples have been examined in most studies examining PPU (Fernandez & Griffiths, Citation2021). Participants with PPU typically report higher QPU relative to healthy volunteers (Gola et al., Citation2017; Prause et al., Citation2015; Voon et al., Citation2014), and typically there exist small-to-moderate associations between QPU and PPU in community samples (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Brand et al., Citation2011; Grubbs, Exline et al., Citation2015; Leonhardt et al., Citation2018; Twohig et al., Citation2009; Wetterneck et al., Citation2012), while stronger, moderate associations have been reported in treatment-seeking and clinical samples (Gola et al., Citation2016; Lewczuk et al., Citation2017). Still, other findings suggest that associations might be stronger in community samples than in treatment-seeking samples (Bőthe, Lonza et al., Citation2020). Thus, clinical/treatment-seeking status is important to consider in understanding associations between QPU and PPU.

Aims of the Present Study

Given variability in strengths of associations between QPU and PPU in different studies, the present study aimed to use meta-analytic methods to evaluate the overall association between QPU and PPU and investigate potential moderators, such as sociodemographic, cultural, and measurement-related characteristics in these associations. Specifically, we explored which measurement characteristics (e.g., assessments of PPU and QPU) and sample characteristics (e.g., gender, sexual orientation, sexual cultural context and sample type) may explain the inconsistent associations between QPU and PPU.

Method

Literature Search

Major electronic databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, ProQuest, Science Direct and Wiley Online Library were searched in November 2019 (first time), April 2020 (second time), August 2020 and (third time), December 2020 (fourth time) for the following search terms: (porn* OR “sexually explicit” OR erotica OR “adult films” OR “adult movies” OR “adult videos” OR “x-rated films” OR “x-rated movies” OR “x-rated videos”) and (problem* OR compul* OR impul* OR addict* OR excess* or dependen*). We searched for these terms in the keywords, title, and abstract sections. The year 1995 was chosen as an initial time for articles given that since the late 1990s the conceptualization of PPU has been proposed and the internet has changed access to pornography (Grubbs et al., Citation2020).

Selection Criteria

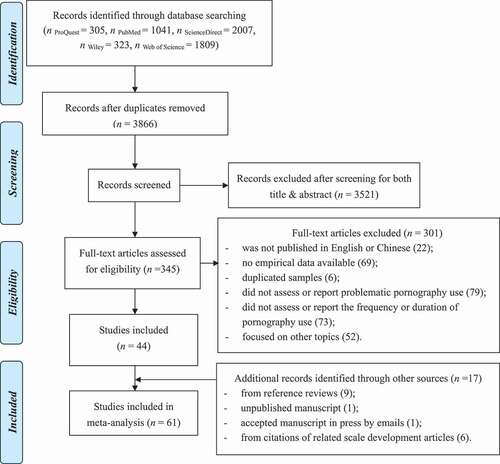

Studies included in this meta-analysis required that they (a) reported original empirical findings; (b) included adult or adolescent samples (if there were multiple reports of the same study sample, the first published report was used); (c) reported associations between QPU (usage time or frequency of PU) and PPU (total score or at least one dimension of PPU)Footnote1; (d) focused on PPU (articles focusing on other topics such as paraphilia, sexual abuse, sex crimes or hypersexuality were not retained)Footnote2; (e) were published in English or Chinese (the languages spoken by the authors). We contacted the papers’ authors to request correlation coefficients if they were not reported in the published article (see for the flow diagram of the article-sele tion process).

Coding and Quality Evaluation

Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts of the identified manuscripts to select articles; then, full-text manuscripts were assessed for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Studies that met inclusion criteria were coded for the following information: first author’s name, year of publication, country, sample size and sample characteristics (i.e., age, gender, sexual orientation, conservative/permissive sexual cultural context, and sample type), measurement of PPU, and measurement of QPU (i.e., frequency or usage time). The classification of conservative/permissive sexual cultural context was based on the sexual value results from The World Values SurveyFootnote3 (WVS, for more details see Supplementary Material 1, Table S1) (Haerpfer et al., Citation2020). The WVS asks about a number of issues related to tolerance toward divorce, abortion, and homosexuality. A low acceptance rate (i.e., lower scores than the average on these items in the WVS) of these issues are considered reflecting conservative values (W. Zheng et al., Citation2011). In the present study, China, Malaysia, and Poland were included in the conservative group, while the permissive countries group included Hungary, Croatia, Canada, Israel, United States, Switzerland, Czech Republic, Germany, Spain, and Australia.

Quality of included studies was assessed by a modified version of the quality appraisal tool recommended by Crombie (Citation1996) for assessment of cross-sectional studies. There are seven criteria to rate the quality of the included studies. These criteria covered “Appropriate research design and statistical analysis,”Footnote4 “Appropriate data collection strategy,”Footnote5 “Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participation,” “Representativeness of samples (age, diversity),” “Reliability of PPU measure (Cronbach’s α in present study),”Footnote6 “Description of QPU measure,” and “Publication status (published or unpublished).” More details about the quality of the included studies are available in Supplementary Material 2, Table S2). The total quality scores ranged from 0 to 7 (M = 6.14, SD = 0.62). The inter-rater reliability of the quality evaluation score was high (r = 0.94). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. summarizes the major characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 61 studies included in the present meta-analysis.

Data Analysis

We calculated r coefficients for effect-size estimates using “metafor” (version 2.4– 0) and “meta” (version 4.12– 0) for R software (version 4.0.2). Effect sizes of at least 0.50 were considered large, 0.30 were considered moderate, and 0.10 were considered small effects (Cohen, Citation1992). Effect sizes were computed using random-effects models. The Q statistic and I2 were used to test heterogeneity of effect sizes. Subgroup analyses with categorical variables (e.g., sexual cultural context, gender, sexual orientation, measurements) and meta-regression analyses with continuous variables (e.g., quality of study, participants’ age, published year, and sample size) were performed to explain observed heterogeneity in effect sizes. In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the overall effect size, sensitivity analyses were conducted using the leave-one-out method and the influential case diagnostics method [i.e., DFFITS value, Cook’s distances, covariance ratios, estimates of τ2 and test statistics for (residual) heterogeneity] (Alemayehu & Hailemariam, Citation2020; Gallo et al., Citation2020; Polanczyk et al., Citation2014; Raboisson et al., Citation2020; Da Silva Chaves et al., Citation2018; Simental-Mendía et al., Citation2018; Wolfgang, Citation2010). To test publication bias, we used funnel plots, Egger’s regression test, and Rosenthal’s Fail-safe N to assess symmetry.

Results

Overall Estimation of Effect Sizes between QPU and PPU

The current meta-analysis included 61 studies with 74,880 participants and 82 independent effect sizes as 15 studies consisted of multiple samples. The effect size of the overall association was r = 0.34 (95%CI = 0.31, 0.37) with the random-effects model. The Q statistic was significant (Q(81) = 1171.73, p < .001) and I2 value was 94.52%, suggesting that there was significant heterogeneity among effect size estimates for the studies in this meta-analysis. In the forest plot of the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for random-effects models (see Supplementary Material 1, Figure S1), we can see how the overall effect estimates change with one study omitted each time. All analyses were robust in the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis because all of the recalculated correlation coefficients remained around 0.34 (95%CI = 0.32, 0.35). Again, the plot of the influence analysis (see Supplementary Material 1, Figure S2) indicated that it was not necessary to remove any data, since no primary study reached the cutoffs proposed by Viechtbauer and Cheung (Harrer et al., Citation2021; Viechtbauer & Cheung, Citation2010; Wolfgang, Citation2010).

Publication Bias

To test for publication bias in the examined manuscripts, a funnel plot was generated (). Most plots were at the top and relatively evenly distributed near the principal axis. However, the funnel plot appeared a little asymmetrical at the top, and the trim-and-fill analysis identified 12 putative missing studies on the right side of the distribution (), suggesting a possible publication bias. Considering the subjective interpretation of the funnel plot, we also used Egger’s regression test and Rosenthal’s Fail-safe N to assess for symmetry. Based on the result of the Egger’s test (Z = −1.15, p = .248), no publication bias was detected. As for Fail-safe N (p < .001), the result showed that at least 202,807 studies with the opposite conclusions would be required to overturn the findings of this meta-analysis. In sum, multiple inspection methods provide little evidence for publication bias in this meta-analysis.

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analyses was conducted to examine characteristics that might explain variance in effect sizes across studies. Results of subgroup analyses are displayed in . As expected, there were significant differences in between-group correlations (QB = 12.66, p = .002). The scales in the framework of addiction showed the strongest associations with QPU (r = 0.39). Moderation analyses showed that the effect size of frequency was significantly larger than that for usage time (QB = 14.49, p < .001), and multi-item measurements had stronger relationships than single-item measurements (QB = 15.44, p < .001).

Table 2. Summary of the results of the sub-group meta-analysis.

As can be seen in , the overall magnitudes of the correlation coefficient did not significantly vary across gender (female vs male; QB = 0.44, p = .506), sexual orientation (mostly sexual minority vs mostly heterosexual samples; QB = 0.13, p = .718) and type of sample (community vs treatment-seeking/clinical; QB = 0.01, p = .916).

Results suggested that cultural context significantly contributed to the heterogeneity in the associations (QB = 5.33, p = .021). The correlation between QPU and PPU was stronger in more conservative countries (rconservative = 0.41 vs rpermissive = 0.33). Although no significant interaction was observed between sexual culture context and gender (p = .246), there was a significant interaction of sexual culture context and theoretical frameworks of PPU (p < .001). In conservative sexual contexts, QPU showed robust association with self-perceived PPU, and weakest relations with PPU based on the obsessive-compulsive framework. The outcomes of meta-regression analyses showed that the magnitude of the r coefficient did not vary according to study quality, participant age, first age exposed to pornography, publication year, and sample size (all ps > 0.076).

Discussion

Given previously reported variability in associations between QPU and PPU (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Chen, Ding et al., Citation2018; Fernandez et al., Citation2017; Gola et al., Citation2016; Grubbs, Exline et al., Citation2015; Grubbs et al., Citation2017; Grubbs & Gola, Citation2019; Grubbs, Kraus et al., Citation2019; Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, Pargament et al., Citation2018; Volk et al., Citation2016; Wéry et al., Citation2016), the present meta-analysis examined the associations between QPU and PPU considering the roles of potential moderators. There was an overall significant, positive and moderate relationship between QPU and PPU (r = 0.34, k = 82). Moreover, the association of QPU and self-perceived PPU was close to that reported by Grubbs and colleagues (r = 0.28, k = 20 vs r = 0.27, k = 10, respectively) (Grubbs, Perry et al., Citation2019). The relationship appeared to be moderated by other factors leading to differences in strengths of the relationships. Subgroup analyses showed that measurements of PPU in different conceptual frameworks may contribute importantly to the strength of the relationships. Frequency of use seemed more robustly related to PPU than usage time. Additionally, QPU and PPU were more strongly associated in more conservative countries in comparison to more sexually permissive countries, regardless of participants’ gender. Associations between QPU and PPU did not vary by gender, treatment-seeking status, sexual orientation, age, publication year, or sample size.

Measurements and Theoretical Frameworks of PPU

When examining associations between QPU and PPU using different measures assessing PPU, effect sizes obtained when using the scales based on addiction frameworks (i.e., PPUS, PPCS) were the largest. These larger effect sizes may derive from the fact that these scales include essential addiction factors, such as salience or tolerance, that may be more strongly related to QPU than other aspects of PPU included in other conceptualizations of PPU (e.g., tolerance refers to the process whereby increased amounts of the activity are required to achieve the former mood modifying effects). Scales developed to assess self-perceived addiction (e.g., CPUI-9) appear to be somewhat less correlated with QPU. Considering that excessive QPU can be considered as an objective indicator of dysregulated PPU (Cooper et al., Citation1999), it was reasonable to find that there were more robust relationships between objective behavior frameworks (i.e., the addiction framework and the obsessive-compulsive framework) and QPU, than frameworks focusing on perceptions of PPU (i.e., self-perceived addiction framework), since perceived addiction refers to subjective distress of inability to control one’s own consumption, regardless of the quantity of actual pornography use (Grubbs, Volk et al., Citation2015). The lesser focus on addictive features and greater focus on subjective addiction may contribute to the weaker associations between QPU and PPU, although some studies using self-perceived PPU scales found particularly strong relationships with frequency of use (Lewczuk et al., Citation2020).

Prior evidence also supported the smallest effect size in the self-perceived addiction framework. Longitudinal findings suggest that participants’ self-perceived addiction may not predict frequency of pornography use over time (Grubbs, Wilt, Exline, & Pargament Citation2018), and low frequency of use may also result in conflict and self-reported problems in pornography use (Chen, Jiang et al., Citation2021). However, individuals with PPU reported both high levels of QPU and features of PPU including and tolerance, and relapse (Bőthe, Lonza et al., Citation2020). Therefore, a practical implication for PPU, assessment would be that, taking into account the possibility of specific individuals overpathologizing their own behavior, items focusing on objective behavior patterns (e.g., “I have had many unsuccessful attempts to reduce my pornography use”) would likely have greater sensitivity compared to items focusing on beliefs or perception (e.g., “I believe I am addicted to pornography”).

Frequency and Usage Time of QPU (Single or Multi-item)

In line with the findings of a recent study (Lewczuk et al., Citation2020), the current study revealed that frequency of use was a more robust quantitative indicator of PPU than usage time. As Busby et al. proposed that pornography is a multidimensional construct (Busby et al., Citation2017, Citation2020), the assessment of frequency should be more diverse and systematic (Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018; Rimington, Citation2008; Wéry et al., Citation2016). Since participants may have different standards as to what constitutes pornography (Kohut et al., Citation2020; McKee et al., Citation2020), when pornography research uses simple single-item measures (e.g., How often have you used pornography during the last 6 months?), some participants may refer to very mild types of sexual media, whereas others will be thinking about extremely graphic types of sexual media (Busby et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, results based on single-item measures may underestimate the prevalence of such experiences and accuracy may be biased by stereotypes about behavioral and sexual experiences (Shaughnessy & Byers, Citation2013). Therefore, researchers are encouraged to use multi-item or multi-dimensional measures of QPU that consider frequency, usage time, content, and other features [e.g., motivations (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Bella et al., Citation2021; Grubbs, Wright et al., Citation2019)]. In order to assess pornography use in a more comprehensive manner, measures with demonstrated content validity and a definition of pornography should be used (Kohut et al., Citation2020), to provide more consistency between different studies (Grubbs et al., Citation2020).

Conservative and Permissive Sexual Cultural Contexts: Interaction with Theoretical Frameworks of PPU

Concerning sexual cultural contexts, there was a significantly larger effect in conservative than in sexually permissive countries in the associations between QPU and PPU. In the conservative sexual contexts, QPU had the strongest association with self-perceived PPU. However, in the sexually more permissive countries, this relationship was relatively stable without significant variations in different PPU theoretical frameworks. In the current study, conservative/permissive sexual cultural contexts were classified based on acceptance of homosexuality, abortion and divorce scores from the WVS. As Young proposed (Citation2001, Citation2008), individuals’ pornography use in more conservative cultures may progress more rapidly to the feeling of PPU (i.e., self-perception of PPU), perhaps due to specific factors (e.g., cultural shame, not knowing how/where to receive help) that may limit behavioral changes at earlier time points. On the other hand, in conservative contexts, individuals may feel that pornography use is in opposition to their cultural values (Grubbs & Perry, Citation2019); thus, any pornography use may be considered problematic. Cultural context and other factors (cultural aspects relating to religion) warrants further research, as do jurisdictional considerations that may be more independent of culture (e.g., with respect to regulation of the internet).

Gender Differences: Interaction with Conservative/permissive Cultures

Previous studies have suggested that relationships between QPU and PPU are weaker among men than women, especially in treatment-seeking settings (Gola et al., Citation2016; Lewczuk et al., Citation2017). However, in the current meta-analysis, gender did not significantly moderate the magnitude of the association between QPU and PPU. Although the prevalence of PPU in women appears to be lower than that in men, a considerable number of women experience PPU (Baranowski et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2012). From the addiction literature (Lev-Ran et al., Citation2013), we know that women usually demonstrate lower prevalence of addictive behaviors than men, but do show a similar symptoms. Several studies have demonstrated that PPU scales have a similar factor structure in men and women, but men show higher levels of PPU in general (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Demetrovics et al., Citation2021; Bőthe, Tóth-Király et al., Citation2018; Chen, Wang et al., Citation2018), suggesting that men and women may have similar features of PPU. In sexually conservative cultures, the association between QPU and PPU was higher among both men and women. In more conservative cultures, non-marital or recreational sexual activities are often stigmatized, and members’ sexuality are controlled (Guo, Citation2019), which makes it riskier for these individuals to use pornography and may exacerbate their conflict.

Treatment-seeking Status

Although no significant differences were found in effect sizes in treatment-seeking and community samples, recent research suggested that withdrawal and tolerance may be particularly important factors in treatment-seeking individuals (Chen, Luo et al., Citation2021), and these features may underlie frequent pornography use (Sussman & Sussman, Citation2011). That is, QPU may be more strongly associated with PPU among individuals who sought treatment for compulsive use, and this may reflect processes of tolerance and withdrawal. Primarily non-clinical samples have been used in most studies of PPU; among the 61 included studies, only 5 studies covered treatment/help-seeking participants, which may explain the non-significant difference between the treatment-seeking and community samples. More research is needed to investigate relationships between QPU and PPU in clinical/ treatment-seeking populations, as well as to assess the relevance of tolerance and withdrawal for behavioral addictions more broadly.

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation may potentially influence relationships between QPU and PPU (Brand, Brand, Antons et al., Citation2019). Sexual minority groups have been reported to engage in more frequent pornography use, and spend more time with it (Downing et al., Citation2017), possibly because they have more obstacles to find sexual or romantic partners (Bőthe et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, no significant moderation effects of sexual orientation on associations between QPU and PPU were observed, which may be due to the fact that sexual excitability and pleasure acquired from pornography use can be similar for sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. For example, Laier et al. found that sexual excitability from pornography use seemed to be independent from gender and sexual orientation (Laier et al., Citation2014, Citation2015). Brain imaging findings comparing neural activations of homosexual and heterosexual men when presenting sexually relevant cues also supported this notion (Paul et al., Citation2008).

Limitations and Future Studies

The present study was not without limitations. First, the studies included in the meta-analysis mostly used self-report scales, and no clinical examinations were conducted, which may bias the results. Second, available studies largely lacked sizable numbers of sexual minority individuals or did not state explicitly participants’ sexual orientations. Thus, there may have been insufficient sample sizes to evaluate main and interaction effects, including interactions between gender and sexual orientation, or sexual cultural context and sexual orientation. Third, although some studies suggested links between religiosity and self-perceived PPU (Bradley et al., Citation2016; Grubbs, Exline et al., Citation2015; Grubbs & Perry, Citation2019; Wéry et al., Citation2016), few studies explicitly compared atheist and religious samples, which limits possibilities for more detailed analyses. It may be important for future studies to conduct more investigations in sexual minority samples and religious samples in order to obtain enough study findings to carry out future meta-analysis to generate a more systematic understanding of interactions between these variables.

Additionally, studies typically did not examine pornography content, and some pornographic content [e.g., objectification of and violence toward women (Bridges et al., Citation2010) and themes of rape, incest and racism (Fritz et al., Citation2021; Rothman et al., Citation2015)] may conflict with moral values in ways that may be independent of religion or sexual orientation. Thus, future studies should consider pornography content. Lastly, although the CPUI-9 and CPUI-3 mainly assess self-perceived PPU, they also include items related to compulsive use; in addition, there might be overlap between the addiction and obsessive-compulsive conceptualizations. Therefore, it was not possible to examine these different frameworks completely separately. Although the scales were developed using different theoretical frameworks, they are strongly related; for example, the BPS and PPCS BOTH assess PPU but from a different perspective and were strongly related in previous work (Chen, Jiang et al., Citation2021).

Future studies should consider religion and morality in a more detailed manner to understand what moral incongruence may mean and how it may relate to different sexual cultural contexts. It will be important in future studies to examine relationships between QPU and PPU in longitudinal studies, considering further moderating and mediating factors. For instance, viewing sexually explicit materials may result in more permissive sexual attitudes (Bishop, Citation2015; Peter & Valkenburg, Citation2016), and conservative beliefs about sexual behaviors seem to be particularly related to self-perceptions of PPU for many people. Thus, individuals’ attitudes toward sexuality may be both a mediator and a moderator that should be investigated. A consolidation of theoretical understandings and assessments of pornography use and PPU would be a necessary pre-requisite for future research in this domain. We believe these are key considerations that should underlie current and future efforts to develop or retain measures that are useful and accurate in the assessment of QPU and PPU and based on solid theoretical frameworks and strong empirical evidence. Direct measures of cultural characteristics should also be considered in future studies. Additionally, individual differences such as personality characteristics (e.g., sexual sensation seeking) and level of self-esteem may also be relevant moderators between QPU and PPU (Borgogna, McDermott, et al., Citation2020; Chen, Yang et al., Citation2018). However, given the lack of sufficient number of studies, we were not able to conduct subgroup analyses with these variables.

Conclusion

In general, QPU had a positive, moderate association with PPU. However, the strength of this association was dependent on several factors (i.e., moderators), such as the measurements of PPU or the sexual cultural context. The magnitude of the association was higher in the case of scales using the addiction framework, and for the more sexually conservative countries. Contrary to expectations, gender, sexual orientation, and treatment-seeking status did not moderate the associations between QPU and PPU.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lijun Chen, Huijuan Wu; methodology, Lijun Chen, Xiaoliu Jiang, Beáta Bőthe; formal analysis, Lijun Chen, Xiaoliu Jiang, Qiqi Wang; data collection, Xiaoliu Jiang, Qiqi Wang; resources, Marc. N. Potenza, Lijun Chen; data curation, Lijun Chen, Beáta Bőthe; writing—original draft preparation, Xiaoliu Jiang; writing—review and editing, Lijun Chen, Xiaoliu Jiang, Beáta Bőthe, Marc. N. Potenza, Huijuan Wu; visualization, Xiaoliu Jiang, Qiqi Wang; supervision, Huijuan Wu, Marc. N. Potenza; project administration, Lijun Chen, Huijuan Wu.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.4 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In order to reduce the collinearity deriving from the PPU measurements that included items on both QPU and PPU, we excluded PPU scales that included questions about the frequency of use and usage time. For example, the Internet Sex Screening Test (ISST) comprised items on QPU; thus, we only included the papers in the present study that reported the compulsivity dimension of the ISST separately (not the total score of the ISST).

2 For example, the Sexual Addiction Screening Test-Revised (SAST-R) comprised items that assessed sexual activities in general. Therefore, we did not include studies using the SAST-R.

4 The rating criterion was that studies reported associations between QPU and PPU (total score or at least one dimension of PPU).

5 The rating criterion was the breadth of sample distribution. For instance, given that the sample distribution for online recruitment is much broader than for course recruitment, we rated online survey 1, and other convenient sampling such as course recruited as 0.5.

6 The scoring criterion was whether the study reported the actual Cronbach’s alpha.

References

- Alemayehu, T., & Hailemariam, M. (2020). Prevalence of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus in Africa in one health approach: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 20542. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77696-6

- Antons, S., Mueller, S. M., Wegmann, E., Trotzke, P., Schulte, M. M., & Brand, M. (2019). Facets of impulsivity and related aspects differentiate among recreational and unregulated use of Internet pornography. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.22

- Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro Calvo, J., Dolores Gil-Llario, M., & Gil-Julia, B. (2017). Cybersex addiction: A study on Spanish college students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 567–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2016.1208700

- Baranowski, A. M., Vogl, R., & Stark, R. (2019). Prevalence and determinants of problematic online pornography use in a sample of German women. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(8), 1274–1282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.05.010

- Bishop, C. J. (2015). ‘Cocked, locked and ready to fuck?’: A synthesis and review of the gay male pornography literature. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2014.983739

- Blais-Lecours, S., Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Sabourin, S., & Godbout, N. (2016). Cyberpornography: Time use, perceived addiction, sexual functioning, and sexual satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(11), 649–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0364

- Borgogna, N. C., Isacco, A., & McDermott, R. C. (2020). A closer examination of the relationship between religiosity and problematic pornography viewing in heterosexual men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 27(1–2), 23–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2020.1751361

- Borgogna, N. C., Lathan, E. C., & Mitchell, A. (2018). Is women’s problematic pornography viewing related to body image or relationship satisfaction? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 345–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2018.1532360

- Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Berry, A. T., & Browning, B. R. (2020). Masculinity and problematic pornography viewing: The moderating role of self-esteem. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 21(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000214

- Bőthe, B., Bartók, R., Tóth-Király, I., Reid, R. C., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2265–2276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z

- Bőthe, B., Lonza, A., Štulhofer, A., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Symptoms of problematic pornography use in a sample of treatment considering and treatment non-considering men: A network approach. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(10), 2016–2028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.030

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Bella, N., Potenza, M. N., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2021). Why do people watch pornography? The motivational basis of pornography use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 172–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000603

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2021). The short version of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-6): A reliable and valid measure in general and treatment-seeking populations. Journal of Sex Research, 58(3), 342–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1716205

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Griffiths, M. D., Potenza, M. N., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Are sexual functioning problems associated with frequent pornography use and/or problematic pornography use? Results from a large community survey including males and females. Addictive Behaviors, 112, 106603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106603

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Potenza, M. N., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). High-frequency pornography use may not always be problematic. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(4), 793–811. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.007

- Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Zsila, A., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). The development of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS). Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 395–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1291798

- Bőthe, B., Vaillancourt-Morel, M.-P., Bergeron, S., & Demetrovics, Z. (2019). Problematic and non-problematic pornography use among LGBTQ adolescents: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 6(4), 478–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00289-5

- Bradley, D. F., Grubbs, J. B., Uzdavines, A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2016). Perceived addiction to internet pornography among religious believers and nonbelievers. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 23(2–3), 225–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2016.1162237

- Brahim, F. B., Rothen, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Courtois, R., & Khazaal, Y. (2019). Contribution of sexual desire and motives to the compulsive use of cybersex. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 442–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.47

- Brand, M., Antons, S., Wegmann, E., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). Theoretical assumptions on pornography problems due to moral incongruence and mechanisms of addictive or compulsive use of pornography: Are the two “conditions” as theoretically distinct as suggested? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 417–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1293-5

- Brand, M., Laier, C., Pawlikowski, M., Schächtle, U., Schöler, T., & Altstötter-Gleich, C. (2011). Watching pornographic pictures on the Internet: Role of sexual arousal ratings and psychological–psychiatric symptoms for using Internet sex sites excessively. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(6), 371–377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0222

- Brand, M., Wegmann, E., Stark, R., Müller, A., Wölfling, K., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: Update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 104, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.06.032

- Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

- Bridges, A. J., Wosnitzer, R., Scharrer, E., Sun, C., & Liberman, R. (2010). Aggression and sexual behavior in best-selling pornography videos: A content analysis update. Violence Against Women, 16(10), 1065–1085. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210382866

- Browning, D. S., Green, M. C., & Witte Jr, J. (2006). Sex, marriage, and family in world religions. Columbia University Press.

- Busby, D. M., Chiu, H.-Y., Olsen, J. A., & Willoughby, B. J. (2017). Evaluating the dimensionality of pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1723–1731. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0983-8

- Busby, D. M., Willoughby, B. J., Chiu, H.-Y., & Olsen, J. A. (2020). Measuring the multidimensional construct of pornography: A long and short version of the pornography usage measure. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(8), 3027–3039. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01688-w

- Chelsen, P. O. (2011). An examination of Internet pornography usage among male students at Evangelical Christian colleges [Ph.D., Loyola University Chicago]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Chen, L., Ding, C., Jiang, X., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Frequency and duration of use, craving and negative emotions in problematic online sexual activities. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 396–414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2018.1547234

- Chen, L., Jiang, X., Luo, X., Kraus, S. W., & Bőthe, B. (2021). The role of impaired control in screening problematic pornography use: Evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in a large help-seeking male sample . Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000714

- Chen, L., Jiang, X., Luo, X., Wu, R., & Huang, L. (2020). High frequency of online sexual activities as a variable feature of men’s problematic internet pornography use: Moderating role of sexual attitudes and evidence from public and clinical samples. Manuscript under review, Fuzhou University.

- Chen, L., & Jiang, X. (2020). The assessment of problematic internet pornography use: A comparison of three scales with mixed methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020488

- Chen, L., Luo, X., Bőthe, B., Jiang, X., Demetrovics, Z., & Potenza, M. N. (2021). Properties of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS-18) in community and subclinical samples in China and Hungary. Addictive Behaviors, 112, 106591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106591

- Chen, L., Wang, X., & Chen, S. (2018). Reliability and validity of the Problematic Internet Pornography Use Scale- Chinese Version among college students. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 34(7), 1034–1038. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.04.017

- Chen, L., Yang, Y., Su, W., Zheng, L., Ding, C., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). The relationship between sexual sensation seeking and problematic Internet pornography use: A moderated mediation model examining roles of online sexual activities and the third-person effect. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 565–573. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.77

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., & Burg, R. (2000). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7(1–2), 5–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160008400205

- Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., Griffin-Shelley, E., & Mathy, R. M. (2004). Online sexual activity: An examination of potentially problematic behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(3), 129–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160490882642

- Cooper, A., Scherer, C. R., Boies, S. C., & Gordon, B. L. (1999). Sexuality on the Internet: From sexual exploration to pathological expression. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 30(2), 154–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.30.2.154

- Cooper, A. (1998). Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the new millennium. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 1(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.187

- Crombie, I. K. (1996). The pocket guide to critical appraisal. BMJ Publishing Group.

- da Silva Chaves, S. N., Felício, G. R., Costa, B. P. D., de Oliveira, W. E. A., Lima-Maximino, M. G., Siqueira Silva, D. H. D., & Maximino, C. (2018). Behavioral and biochemical effects of ethanol withdrawal in zebrafish. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 169, 48–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2018.04.006

- Degomez, N. C. (2011). Pornography acceptance and patterns of use among college students, and associations with spirituality and religiosity [Ph.D., Northern Arizona University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Globa.

- Downing, M. J., Antebi, N., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2014). Compulsive use of Internet-based sexually explicit media: Adaptation and validation of the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS). Addictive Behaviors, 39(6), 1126–1130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.007

- Downing, M. J., Schrimshaw, E. W., Scheinmann, R., Antebi-Gruszka, N., & Hirshfield, S. (2017). Sexually explicit media use by sexual identity: A comparative analysis of gay, bisexual, and heterosexual men in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1763–1776. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0837-9

- Duggan, S. J., & McCreary, D. R. (2004). Body image, eating disorders, and the drive for muscularity in gay and heterosexual men. Journal of Homosexuality, 47(3–4), 45–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v47n03_03

- Efrati, Y., & Gola, M. (2018). Treating compulsive sexual behavior. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(2), 57–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0143-8

- Engel, J., Kessler, A., Veit, M., Sinke, C., Heitland, I., Kneer, J., Hartmann, U., & Kruger, T. H. C. (2019). Hypersexual behavior in a large online sample: Individual characteristics and signs of coercive sexual behavior. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.16

- Fernandez, D. P., & Griffiths, M. D. (2021). Psychometric instruments for problematic pornography use: A systematic review. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 44(2), 111–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278719861688

- Fernandez, D. P., Tee, E. Y., & Fernandez, E. F. (2017). Do Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 scores reflect actual compulsivity in internet pornography use? Exploring the role of abstinence effort. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 24(3), 156–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2017.1344166

- Fineberg, N. A., Chamberlain, S. R., Goudriaan, A. E., Stein, D. J., Vanderschuren, L. J. M. J., Gillan, C. M., Shekar, S., Gorwood, P. A. P. M., Voon, V., Morein-Zamir, S., Denys, D., Sahakian, B. J., Moeller, F. G., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). New developments in human neurocognition: Clinical, genetic, and brain imaging correlates of impulsivity and compulsivity. CNS Spectrums, 19(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852913000801

- Fritz, N., Malic, V., Paul, B., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Worse than objects: The depiction of black women and men and their sexual relationship in pornography. Gender Issues, 38(1), 100–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-020-09255-2

- Gallo, G., Tocci, G., Fogacci, F., Battistoni, A., Rubattu, S., & Volpe, M. (2020). Blockade of the neurohormonal systems in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A contemporary meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology, 316, 172–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.05.084

- Gola, M., Lewczuk, K., & Skorko, M. (2016). What matters: Quantity or quality of pornography use? Psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(5), 815–824. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.169

- Gola, M., Wordecha, M., Sescousse, G., Lew-Starowicz, M., Kossowski, B., Wypych, M., Makeig, S., Potenza, M. N., & Marchewka, A. (2017). Can pornography be addictive? An fMRI study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(10), 2021–2031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2017.78

- Green, B. A., Carnes, S., Carnes, P. J., & Weinman, E. A. (2012). Cybersex addiction patterns in a clinical sample of homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual men and women. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19(1–2), 77–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2012.658343

- Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

- Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2011.588351

- Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Hook, J. N., & Carlisle, R. D. (2015). Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z

- Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Volk, F., & Lindberg, M. J. (2017). Internet pornography use, perceived addiction, and religious/spiritual struggles. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1733–1745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0772-9

- Grubbs, J. B., & Gola, M. (2019). Is pornography use related to erectile functioning? Results from cross-sectional and latent growth curve analyses. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(1), 111–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.11.004

- Grubbs, J. B., Grant, J. T., Lee, B. N., Hoagland, K. C., Davison, P., Reid, R. C., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Sexual addiction 25 years on: A systematic and methodological review of empirical literature and an agenda for future research. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101925. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101925

- Grubbs, J. B., Kraus, S. W., Perry, S. L., Lewczuk, K., & Gola, M. (2020). Moral incongruence and compulsive sexual behavior: Results from cross-sectional interactions and parallel growth curve analyses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(3), 266–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000501

- Grubbs, J. B., Kraus, S. W., & Perry, S. L. (2019). Self-reported addiction to pornography in a nationally representative sample: The roles of use habits, religiousness, and moral incongruence. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(1), 88–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.134

- Grubbs, J. B., Lee, B. N., Hoagland, K. C., Kraus, S. W., & Perry, S. L. (2020). Addiction or transgression? Moral incongruence and self-reported problematic pornography use in a nationally representative sample. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(5), 936–946. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620922966

- Grubbs, J. B., Perry, S. L., Wilt, J. A., & Reid, R. C. (2019). Pornography problems due to moral incongruence: An integrative model with a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 397–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1248-x

- Grubbs, J. B., & Perry, S. L. (2019). Moral incongruence and pornography use: A critical review and integration. Journal of Sex Research, 56(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1427204

- Grubbs, J. B., Sessoms, J., Wheeler, D. M., & Volk, F. (2010). The Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory: The development of a new assessment instrument. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(2), 106–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720161003776166

- Grubbs, J. B., Stauner, N., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Lindberg, M. J. (2015). Perceived addiction to internet pornography and psychological distress: Examining relationships concurrently and over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000114

- Grubbs, J. B., Volk, F., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2015). Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2013.842192

- Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Kraus, S. W. (2018). Moral disapproval and perceived addiction to internet pornography: A longitudinal examination. Addiction, 113(3), 496–506. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14007

- Grubbs, J. B., Wilt, J. A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2018). Predicting pornography use over time: Does self-reported “addiction” matter? Addictive Behaviors, 82, 57–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.028

- Grubbs, J. B., Wright, P. J., Braden, A. L., Wilt, J. A., & Kraus, S. W. (2019). Internet pornography use and sexual motivation: A systematic review and integration. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(2), 117–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1584045

- Guo, Y. (2019). Sexual double standards in white and Asian Americans: Ethnicity, gender, and acculturation. Sexuality & Culture, 23(1), 57–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-018-9543-1

- Haerpfer, C., Inglehart, R., Moreno, A., Welzel, C., Kizilova, K., Diez-Medrano, J., Lagos, M., Norris, P., Ponarin, E., & Puranen, B. (2020). World values survey: Round seven–country-pooled datafile. JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.1

- Hald, G. M. (2006). Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(5), 577–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9064-0

- Harper, C., & Hodgins, D. C. (2016). Examining correlates of problematic internet pornography use among university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 179–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.022

- Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Doing Meta-Analysis With R: A Hands-On Guide (1st ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC Press. https://www.routledge.com/Doing-Meta-Analysis-with-R-A-Hands-On-Guide/Harrer-Cuijpers-Furukawa-Ebert/p/book/9780367610074

- Hatch, S. G., Esplin, C. R., Hatch, H. D., Halstead, A., Olsen, J., & Braithwaite, S. R. (2020). The Consumption of Pornography Scale - General (COPS - G). Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–25. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2020.1813885

- Karila, L., Wéry, A., Weinstein, A., Cottencin, O., Petit, A., Reynaud, M., & Billieux, J. (2014). Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: Different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4012–4020. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990619

- Kim, J. (2009). Asian American women’s retrospective reports of their sexual socialization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33(3), 334–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01505.x

- Klein, S., Kruse, O., Markert, C., Tapia León, I., Strahler, J., & Stark, R. (2020). Subjective reward value of visual sexual stimuli is coded in human striatum and orbitofrontal cortex. Behavioural Brain Research, 393, 112792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112792

- Klucken, T., Wehrum-Osinsky, S., Schweckendiek, J., Kruse, O., & Stark, R. (2016). Altered appetitive conditioning and neural connectivity in subjects with compulsive sexual behavior. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(4), 627–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.013

- Kohut, T., Balzarini, R. N., Fisher, W. A., Grubbs, J. B., Campbell, L., & Prause, N. (2020). Surveying pornography use: A shaky science resting on poor measurement foundations. Journal of Sex Research, 57(6), 722–742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1695244

- Kohut, T., & Stulhofer, A. (2018). The role of religiosity in adolescents’ compulsive pornography use: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(8), 759–775. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2018.1466012

- Kor, A., Zilcha-Mano, S., Fogel, Y. A., Mikulincer, M., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Psychometric development of the Problematic Pornography Use Scale. Addictive Behaviors, 39(5), 861–868. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.027

- Kraus, S. W., Gola, M., Grubbs, J. B., Kowalewska, E., Hoff, R. A., Lew-Starowicz, M., Martino, S., Shirk, S. D., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Validation of a Brief Pornography Screen across multiple samples. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 259–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.027

- Kraus, S. W., Martino, S., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Clinical characteristics of men interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 169–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.036

- Kraus, S. W., Sturgeon, J. A., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Specific forms of passionate attachment differentially mediate relationships between pornography use and sexual compulsivity in young adult men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 380–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2018.1532362

- Kraus, S. W., & Sweeney, P. J. (2019). Hitting the target: Considerations for differential diagnosis when treating individuals for problematic use of pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 431–435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1301-9

- Kraus, S. W., Voon, V., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction, 111(12), 2097–2106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13297

- Kuhn, S., & Gallinat, J. (2014). Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: The brain on porn. Jama Psychiatry, 71(7), 827–834. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.93

- Laier, C., Pekal, J., & Brand, M. (2014). Cybersex addiction in heterosexual female users of internet pornography can be explained by gratification hypothesis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(8), 505–511. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0396

- Laier, C., Pekal, J., & Brand, M. (2015). Sexual excitability and dysfunctional coping determine cybersex addiction in homosexual males. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(10), 575–580. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0152

- Leonhardt, N. D., Busby, D. M., & Willoughby, B. J. (2021). Do you feel in control? Sexual desire, sexual passion expression, and associations with perceived compulsivity to pornography and pornography use frequency. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00465-7

- Leonhardt, N. D., Willoughby, B. J., & Young-Petersen, B. (2018). Damaged goods: Perception of pornography addiction as a mediator between religiosity and relationship anxiety surrounding pornography use. Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1295013

- Lev-Ran, S., Le Strat, Y., Imtiaz, S., Rehm, J., & Le Foll, B. (2013). Gender differences in prevalence of substance use disorders among individuals with lifetime exposure to substances: Results from a large representative sample. The American Journal on Addictions, 22(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00321.x

- Levin, M. E., Lee, E. B., & Twohig, M. P. (2019). The role of experiential avoidance in problematic pornography viewing. Psychological Record, 69(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-018-0302-3

- Lewczuk, K., Glica, A., Nowakowska, I., Gola, M., & Grubbs, J. B. (2020). Evaluating pornography problems due to moral incongruence model. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(2), 300–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.11.259

- Lewczuk, K., Szmyd, J., Skorko, M., & Gola, M. (2017). Treatment seeking for problematic pornography use among women. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.063

- Martyniuk, U., Briken, P., Sehner, S., Richter-Appelt, H., & Dekker, A. (2016). Pornography use and sexual behavior among Polish and German university students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 42(6), 494–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1072119

- McKee, A., Byron, P., Litsou, K., & Ingham, R. (2020). An interdisciplinary definition of pornography: Results from a global Delphi panel. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(3), 1085–1091. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01554-4

- Meerkerk, G. J., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Vermulst, A. A., & Garretsen, H. F. (2009). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181

- Mennig, M., Tennie, S., & Barke, A. (2020). A psychometric approach to assessments of problematic use of online pornography and social networking sites based on the conceptualizations of internet gaming disorder. Bmc Psychiatry, 20(1), 318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02702-0

- Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P. D., & Gorzalka, B. B. (1996). Ethnic and gender differences in sexuality: Variations in sexual behavior between Asian and non-Asian university students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25(1), 33–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02437906

- Morgan, E. M. (2011). Associations between young adults’ use of sexually explicit materials and their sexual preferences, behaviors, and satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 48(6), 520–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.543960

- Noor, S. W., Rosser, B. R. S., & Erickson, D. J. (2014). A brief scale to measure problematic sexually explicit media consumption: Psychometric properties of the Compulsive Pornography Consumption (CPC) Scale among men who have sex with men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21(3), 240–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2014.938849

- Okazaki, S. (2002). Influences of culture on Asian Americans’ sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 39(1), 34–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552117

- Parsons, J. T., Kelly, B. C., Bimbi, D. S., DiMaria, L., Wainberg, M. L., & Morgenstern, J. (2008). Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(5), 817–826. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8

- Paul, T., Schiffer, B., Zwarg, T., Krüger, T. H., Karama, S., Schedlowski, M., Forsting, M., & Gizewski, E. R. (2008). Brain response to visual sexual stimuli in heterosexual and homosexual males. Human Brain Mapping, 29(6), 726–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20435

- Pawlikowski, M., Nader, I. W., Burger, C., Stieger, S., & Brand, M. (2014). Pathological internet use - It is a multidimensional and not a unidimensional construct. Addiction Research & Theory, 22(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2013.793313

- Pekal, J., Laier, C., Snagowski, J., Stark, R., & Brand, M. (2018). Tendencies toward Internet-pornography-use disorder: Differences in men and women regarding attentional biases to pornographic stimuli. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.70

- Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). Adolescents and pornography: A review of 20 years of research. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 509–531. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441

- Petersen, J., & Hyde, J. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993-2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

- Polanczyk, G. V., Willcutt, E. G., Salum, G. A., Kieling, C., & Rohde, L. A. (2014). ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 434–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt261

- Prause, N., Steele, V. R., Staley, C., Sabatinelli, D., & Hajcak, G. (2015). Modulation of late positive potentials by sexual images in problem users and controls inconsistent with “porn addiction.” Biological Psychology, 109, 192–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.06.005

- Raboisson, D., Ferchiou, A., Pinior, B., Gautier, T., Sans, P., & Lhermie, G. (2020). The use of meta-analysis for the measurement of animal disease burden: Losses due to clinical mastitis as an example. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7(12), 149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00149

- Reid, R. C. (2016). Additional challenges and issues in classifying compulsive sexual behavior as an addiction. Addiction, 111(12), 2111–2113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13370

- Rimington, D. D. (2008). Examining the perceived benefits for engaging in cybersex behavior among college students [Master’s thesis, Utah State University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Rothman, E. F., Kaczmarsky, C., Burke, N., Jansen, E., & Baughman, A. (2015). “Without porn … i wouldn’t know half the things i know now”: A qualitative study of pornography use among a sample of urban, low-income, black and Hispanic youth. Journal of Sex Research, 52(7), 736–746. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.960908

- Rousseau, A., Bothe, B., & Stulhofer, A. (2021). Theoretical antecedents of male adolescents’ problematic pornography use: A longitudinal assessment. Journal of Sex Research, 58(3), 331–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1815637