ABSTRACT

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are associated with high rates of hospitalizations, costs, and morbidity. Therefore, hospitalists and the multidisciplinary team (hospital team) need to take a proactive approach to ensure patients are effectively managed from hospital admission to postdischarge. Comprehensive screening and diagnostic testing of patients at admission will enable an accurate diagnosis of COPD exacerbations, and severity, as well as other factors that may impact the length of hospital stay. Depending on the exacerbation severity and cause, pharmacotherapies may include short-acting bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and antibiotics. Oxygen and/or ventilatory support may benefit patients with demonstrable hypoxemia. In preparation for discharge, the hospital team should ensure that patients receive the appropriate maintenance therapy, are counseled on their medications including inhalation devices, and proactively discuss smoking cessation and vaccinations. For follow-up, effective communication can be achieved by transferring discharge summaries to the primary care physician via an inpatient case manager. An inpatient case manager can support both the hospitalist and the patient in scheduling follow-up appointments, sending patient reminders, and confirming that a first outpatient visit has occurred. A PubMed search (prior to 26 January 2021) was conducted using terms such as: COPD, exacerbation, hospitalization. This narrative review focuses on the challenges the hospital team encounters in achieving optimal outcomes in the management of patients with COPD exacerbations. Additionally, we propose a novel simplified algorithm that may help the hospital team to be more proactive in the diagnosis and management of patients with COPD exacerbations.

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough and/or sputum production) and airflow limitation, and is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality [Citation1]. It is currently ranked as the fourth leading cause of death worldwide, and is expected to become the world’s third leading cause of death by 2030 [Citation2–5]. Although more than 16.4 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with COPD, it is estimated that millions more have not yet been diagnosed [Citation2]. The global burden of COPD is expected to increase as a result of persistent exposure to known risk factors [Citation6] such as tobacco smoke [Citation7], biomass fuel, and air pollution [Citation8,Citation9]. Nevertheless, COPD remains an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition. A retrospective analysis of more than 51,000 patients highlighted significant undertreatment in typical US commercially insured and Medicare populations. Most patients with diagnosed COPD remained undertreated, with no maintenance COPD pharmacotherapy over the 1-year study period, highlighting the need for more effective management of the disease [Citation10].

COPD exacerbations are one of the most frequent causes of hospitalizations [Citation11,Citation12]; they can affect the severity of COPD and contribute to increased symptoms [Citation13]. A previous study showed that patients with severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations (≤6-month intervals; >3 per year) had more rapid decline in lung function and worse health-related quality of life than those who had infrequent exacerbations [Citation14]. A recently reported concerning trend indicated that after admission for COPD exacerbations, approximately 20% of patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge [Citation15]. These early readmissions can increase morbidity and mortality and contribute significantly to the economic burden of COPD. A previous study reported that patients who survived severe exacerbations of COPD were at an increased risk of death (21% at 1 year and 55% at 5 years after discharge) and rehospitalization (25% at 1 year and 44% at 5 years after discharge) [Citation16].

Direct COPD costs are almost $50 billion in the United States annually [Citation17], and total COPD care-related costs can be up to twice the identified direct costs because of comorbidities and costs of lost work days [Citation18–20]. COPD exacerbations are responsible for up to 70% of COPD-related health care costs; hospital readmissions alone account for more than $15 billion in direct costs annually [Citation18,Citation19]. COPD costs will vary globally since these costs depend on how health care is provided and paid.

Evidence-based preventative and management strategies of COPD exacerbations are crucial in the management of patients with COPD. Such strategies include assessment and monitoring of the condition and appropriate pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management of patients to reduce the risk of hospitalization [Citation1]. A multifaceted approach would include effective transitions across care settings, engagement with key members of the multidisciplinary team as necessary, and counseling of patients about their medications and inhalation devices [Citation21]. Such measures could reduce the risk of repeated admissions, thus improving outcomes and quality of life for patients and reducing overall cost of care [Citation22–25].

In this narrative review, we discuss the challenges that the hospitalists and the multidisciplinary team (hospital team) encounter in the management of patients admitted with COPD exacerbation. We propose a novel simplified algorithm to assist the hospital team to be more proactive in diagnosing and managing patients with COPD exacerbation.

2. Selection of articles for review

A PubMed search (prior to 26 January 2021) was conducted using numerous primary topic headings combined with appropriate terms for each section of the article (eg, COPD + exacerbation + hospitalization or COPD + exacerbation + hospital discharge). The results of the PubMed search were supplemented by relevant papers from reference lists of published articles.

3. Evaluation of patients with a COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization

Several factors that can lead to a COPD exacerbation have been identified. In most cases, the precipitant factor is a respiratory tract infection (viral or bacterial) [Citation26], but in approximately one-third of severe COPD exacerbations, a cause cannot be identified [Citation1]. Clinical symptoms such as increased sputum purulence could indicate a bacterial causation [Citation27]. Hospitalists often must initiate empiric management of patients with suspected COPD exacerbations. Although hospitalists may not always have ready access to results from microbiological culture or molecular methods, awareness of some of the bacterial or viral strains associated with exacerbations is important () [Citation26, Citation28–30]. Common bacterial strains associated with exacerbations include Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [Citation26]. Common viral strains include rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus [Citation26].

Figure 1. Causes of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation26,Citation28–30].

![Figure 1. Causes of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Citation26,Citation28–30].](/cms/asset/fe0fa212-95bd-434f-8f76-e70ef8241640/ipgm_a_2018257_f0001_c.jpg)

COPD exacerbations are typically stratified as mild, moderate, or severe according to clinical presentation and/or health care resource utilization [Citation31]. Severe symptoms, respiratory failure, changes in mental status, shock or hemodynamic instability, cyanosis, edema, and arrhythmia are important indicators for hospitalization. Comprehensive screening of patients at admission may have an impact on the length of hospital stay. Simple questions to patients and caregivers would allow the hospitalist to identify comorbidities and social factors that may require additional management and affect postdischarge care, such as cognitive or physical limitations, risk of falling, poor nutrition, and elderly neglect or self-neglect. Therefore, proactively identifying these factors at screening would enable the hospitalist to triage cases appropriately [Citation32].

Aside from respiratory tract infections, proactive screening of other factors associated with exacerbations, such as comorbidities [Citation28] and nonadherence to medications would enable hospitalists to identify potential issues with treatment [Citation29]. Comorbid conditions such as ischemic heart disease and congestive heart failure [Citation33,Citation34] are common with COPD; evaluation with cardiac enzymes or B-type natriuretic peptide may also be beneficial. Other diseases that may mimic or coexist with a COPD exacerbation include pneumonia, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and pulmonary embolism [Citation1,Citation28]. In addition to assessment of symptoms and smoking history, spirometry is recommended once the patient’s condition is stabilized, particularly in patients who have not undergone this prior to hospitalization to ascertain COPD diagnosis. Because poor adherence to medication is common in the management of COPD and many patients do not use their inhalers appropriately [Citation35,Citation36], these issues may need to be addressed when patients are stabilized. Particular attention should be given to patient populations with cognitive or physical impairments such as manual dexterity issues or suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFR), who often cannot use their inhalers adequately [Citation36–38]. Poor inhaler technique in such patients may lead to worsening outcomes and increased risk of rehospitalization [Citation39].

An accurate and reliable diagnosis of COPD exacerbations made during hospitalization provides hospitalists with an opportunity to optimize treatment and educate patients about disease management, with the goals of resolving exacerbations, improving long-term outcomes, and preventing future hospitalizations.

4. Pharmacological management strategies during hospitalization

Three groups of medications most commonly used for COPD exacerbations are bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and antibiotics [Citation1]. Short-acting β2-agonists, with or without short-acting muscarinic antagonists, are recommended for the initial management of a COPD exacerbation [Citation1]. To achieve optimal outcomes during hospitalization, delivery of bronchodilator treatment with a nebulizer or a metered-dose inhaler with spacer may be the most appropriate options. Hospitalists should determine whether the patient has been using other COPD medications at home and whether these should be continued during the hospital setting. Such medications may include maintenance treatments for COPD such as long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), LABA/inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) combinations, theophylline, and oral phosphodisterase-4 inhibitors [Citation1]. However, clinical studies evaluating the usefulness of long-acting bronchodilators for the treatment of patients during a COPD exacerbation have demonstrated limited efficacy and increased costs [Citation40,Citation41]. Thus, hospitalists should consider if these treatments are appropriate in an acute setting. Furthermore, The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report recommends initiating long-acting bronchodilators as soon as possible, prior to hospital discharge [Citation1].

Exacerbations that are refractory to short-acting bronchodilators may require additional treatment with systemic corticosteroids. If such therapy is indicated, the GOLD report has suggested a course of 5 to 7 days, depending on patient response. A systematic review of 16 studies showed that a 7-day course of systemic corticosteroids decreased the risk of relapse, the risk of treatment failure, and hospitalization duration [Citation42]. Furthermore, the REDUCE trial demonstrated that a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily was noninferior to a 14-day course in patients who presented to the emergency department with a COPD exacerbation, with respect to reexacerbation [Citation43]. Prolonged courses of corticosteroids are generally not required because hospitalized patients achieved the maximum benefit in the first week of treatment [Citation44]. If the patient is able to tolerate oral administration, oral corticosteroids can be considered. The use of low-dose oral corticosteroids was shown to be associated with outcomes equal, if not superior, to high-dose intravenous therapy [Citation45].

It is recommended that initiation of antibiotics is considered based on the patient’s clinical picture and the presence of increased sputum purulence [Citation27]. When indicated, antibiotics may also reduce recovery time and hospitalization duration [Citation46,Citation47]. Depending on patient response, treatment for 5 to 7 days is recommended [Citation1]. A meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar efficacy among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days [Citation48]. A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical efficacy, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis [Citation48,Citation49]. Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved patient adherence and decreased rates of antibiotic resistance [Citation50]. Hospitalists should initiate antibiotic treatment according to the local sensitivity or resistance patterns and the exposure to risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia [Citation51]. Typical first-line empiric antibiotics include doxycycline or azithromycin [Citation52,Citation53]. If patients are already on chronic azithromycin therapy for frequent exacerbations, an antibiotic regimen that does not include azithromycin should be prescribed. Therapeutic responses can be assessed after 2 to 3 days of treatment [Citation54]. In patients with more severe exacerbations, gram-negative bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa may be present, and typical first-line empiric antibiotics would not be appropriate in this instance [Citation1]. Anti-pseudomonal antibiotics include levofloxacin, cefepime, ceftazidime, and piperacillin-tazobactam [Citation52,Citation53].

The GOLD report recommends that patients with demonstrable hypoxemia are treated with supplemental oxygen, with a target saturation of 88% to 92%. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation should be considered in patients with acute respiratory failure [Citation1]. In patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, it is recommended that patients are treated using heated humidified high flow nasal cannula oxygen that delivers precisely controlled inspired oxygen (FiO2) at higher flow rates to help improve oxygen saturation (SpO2), and reduce work of breathing.

5. Hospital discharge

Patients are typically ready for discharge when they meet certain criteria, such as when they achieve hemodynamic stability, when their symptoms improve, and when their eating, drinking, and sleeping are no longer interrupted by dyspnea [Citation1]. Upon discharge, hospitalists should ensure that patients are prescribed the appropriate maintenance therapy, that they can use their inhalation devices appropriately, and are counseled on their medications. Involving pharmacists and respiratory therapists is imperative, as they can help determine if an inhalation device is appropriate and counsel on inhaler technique or nebulized therapy options. Discharging patients on an inhalation delivery device with suboptimal technique could lead to worsening outcomes, increased symptom burden, and increased hospitalizations [Citation55]. Including pharmacists and respiratory therapists in COPD care has been associated with a reduction in hospital admissions [Citation56,Citation57]. Certain patient populations, such as those who have cognitive or physical impairments or patients with manual dexterity issues, may find nebulizers more beneficial than handheld inhalers [Citation36–38]. Furthermore, where applicable, reducing the complexity of treatment regimens has the potential to reduce discontinuation and improve adherence. Treatment complexity may be decreased by considering combination inhalers versus separate monotherapy inhalers [Citation58].

Suboptimal PIFR is another factor to be taken into account when considering inhalation devices. PIFR, a measure of a patient’s inspiratory effort, can be used to assess a patient’s ability to generate adequate inspiratory flow from dry powder inhalers (DPIs). Each type of DPI has a unique internal resistance, and patients must be able to generate a PIFR that is sufficient to overcome the internal resistance of the device to disaggregate the powdered drug into fine particles for lung deposition. A handheld inspiratory flow meter with an adjustable dial to simulate internal resistances of DPIs (the In-Check™ DIAL G16) can be used to assess whether a patient can achieve an optimal PIFR. The In-Check™ DIAL G16 includes five resistance groups for DPIs classified as low (one device), medium low (three devices), medium (three devices), medium high (three devices), and high (two devices) [Citation59]. Observational studies have shown suboptimal PIFR in 19% to 78% of stable outpatients with COPD and 32% to 47% of inpatients admitted for a COPD exacerbation [Citation30,Citation60–64]. Patients may not be able to use their DPI adequately, and should therefore have their inhaler technique thoroughly assessed prior to discharge to ensure they are matched to the right inhalation delivery device [Citation62]. Discharging patients on an inhalation delivery device with suboptimal technique could lead to worse outcomes, increased symptom burden, and increased hospitalizations [Citation30,Citation60–64]. The In-CheckTM DIAL G16 can assess the patients’ ability to use different inhaler devices and train them to inhale at a flow rate known to be appropriate for their DPI or metered dose inhaler. Healthcare personnel, such as respiratory therapists or pharmacists, can help inform patients on inhaler technique/maneuvers. If the patient cannot achieve the flow rate needed for their inhaler, a more suitable device can be chosen [Citation59].

The GOLD report recommends pharmacological treatment for maintenance therapy according to patients’ disease severity [Citation1]. Airflow limitation, history of moderate and severe exacerbations, and symptom burden are evaluated to determine optimal treatment. Dyspnea is measured according to the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale or symptoms according to COPD Assessment Test (CAT). Treatments may include single, dual, or triple bronchodilator therapy (LABA, LAMA, LABA/LAMA, LABA/ICS, LABA/LAMA/ICS), roflumilast, or azithromycin. Treatment can be escalated or de-escalated depending on the presence of dyspnea and exercise limitation, and the continued occurrence of exacerbations. Furthermore, a high blood eosinophil count (>300 cells/µl), and patients with a history of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations despite long-term bronchodilator maintenance treatment may guide the initiation of ICS treatment [Citation1].

Hospitalists have the opportunity to proactively implement measures such as smoking cessation and vaccinations, which decrease the risk of a COPD exacerbation. Smoking cessation needs to be emphasized to all current smokers, as this measure is the only known means of delaying COPD progression [Citation65]. The mainstay therapy for smoking cessation is counseling in combination with varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy, or bupropion [Citation66]. In addition, hospitalists are uniquely positioned to recommend appropriate vaccinations as preventive measures. The GOLD report recommends influenza vaccination in all patients with COPD [Citation1]. This recommendation is based on evidence, such as decreased rates of exacerbation, mortality, and hospitalization in patients with COPD [Citation67,Citation68]. In addition, the GOLD report recommends pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for all patients with COPD aged ≥65 years or for those <65 years with a forced expiratory volume in 1 second <40% of predicted [Citation1]. A systematic review of 12 clinical trials reported that pneumococcal vaccination reduces the risk of community-acquired pneumonia and also significantly reduced the risk of an exacerbation in patients with COPD [Citation69]. In addition to smoking cessation and vaccinations, pulmonary rehabilitation is a core component in the long-term management of COPD [Citation70]. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive intervention that involves exercise training, education, and behavior change to improve the physical and psychological condition of patients with chronic disease, including COPD. A wide range of healthcare professionals are generally involved, and these may include pulmonologists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, nutritionists, exercise physiologists, nurses, and psychologists [Citation71]. The GOLD report recommends that patients undergo pulmonary rehabilitation within 1 month following a COPD exacerbation [Citation1] based on evidence supporting improved dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and health-related quality of life compared with usual care [Citation72]. Thus, patients with COPD should be considered and referred for pulmonary rehabilitation whenever applicable.

Hospitalists should also address comorbidities in patients with COPD admitted to the hospital and consider consulting with appropriate specialists as necessary. Comorbidities should be treated per usual standards irrespective of the presence of COPD [Citation1]. Common comorbidities among patients with COPD include cardiac disease, psychiatric disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, and gastroesophageal reflux disease [Citation73,Citation74]. For the management of a cardiovascular comorbidity, pharmacologic treatments should be used for the same indications and treatment targets as in patients without COPD [Citation75,Citation76]. Patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea will require an assessment by a sleep specialist following discharge. Continuous positive airway pressure was associated with improved survival and decreased hospitalizations and thus should be considered in patients with COPD and obstructive sleep apnea [Citation77]. Patients with depression and/or anxiety will need to be assessed by a psychiatrist. Anxiety and depression contribute to a substantial burden of COPD-related morbidity, notably by impairing quality of life and reducing adherence to treatment [Citation78]. Patients with features related to a poor prognosis, such as severe airflow obstruction, frequent exacerbations, and requirement for long-term oxygen therapy, may require discussions on end-of-life care. The hospital palliative care team would play a role in delivering advice and liaising with community services [Citation79].

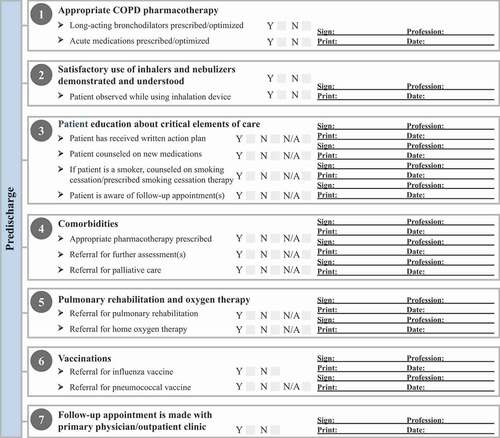

Self-management action plans and medication reconciliation are important for patients with COPD who are transitioning from the hospital setting [Citation80]. Action plans may encourage self-management and use of appropriate treatments among patients with COPD [Citation81]. The importance of maintenance treatments for long-term care should be emphasized, and the use of emergency medications (eg, short-acting bronchodilators, antibiotics, and oral corticosteroids) in case of another exacerbation. The COPD action plan should instruct patients to contact their case manager, hospitalist, or primary care physician (PCP) immediately if symptoms return or worsen to guarantee that the appropriate measures are taken and to decrease the risk of hospitalization. Manual or automated hospital discharge checklists may enable the health care team to communicate appropriate next steps with patients, caregivers, and outpatient health care providers. A predischarge COPD algorithm is proposed in .

6. Transitions of care

Patients with COPD should continue to be managed outside the hospital to prevent relapses, which may occur in approximately one-third of patients within 8 weeks of discharge [Citation82] and result in increased readmission rates [Citation16]. Some patients experiencing a COPD exacerbation have concerns about access to medical care should they become dyspneic again postdischarge [Citation83]. Hospitalists are involved with patients from admission to discharge and are therefore in a key position to alleviate such anxieties. A health care team trained to manage transitions from acute to chronic care is a key aspect of an effective care transition program [Citation84].

Follow-up or venues for patients who are discharged from the hospital may include PCPs, pulmonologists, discharge clinics, visiting nurse services in the patients’ own homes (with support from visiting nurse services), or hospices, which depends on insurance, needs, and other resources. Inpatient case managers can assist with the transition of care. Nurse case management has been shown to reduce the readmission rate of patients with chronic complex disease after hospital discharge, as well as their use of primary care services [Citation85]. Hospitalists need to improve communication with PCPs to improve the management of patients with COPD. A systematic review demonstrated a communication deficit between hospitalists and PCPs, with discharge summaries frequently unavailable at the first postdischarge visit [Citation86]. Effective communication can be achieved by the inpatient case managers transferring discharge summaries prepared by hospitalists to PCPs as soon as possible [Citation84]. They can support both hospitalists and patients in scheduling follow-up appointments, sending patient reminders, and confirming that a first outpatient visit has occurred. For patients without an outpatient physician, inpatient case managers may rely on a list of PCPs willing to receive unassigned patients [Citation87]. Furthermore, hospitalist-led discharge clinics can accommodate patients without a PCP [Citation88]. Patients should be referred if they are considered high risk (eg, having an increased risk of death or rehospitalization) [Citation88]. Characteristics attributed to high-risk patients discharged after a severe exacerbation include older age, low body mass index, lung cancer, cardiovascular conditions, and prior hospitalizations [Citation89].

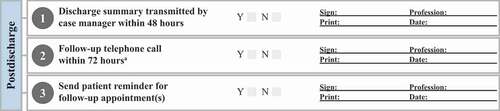

Follow-up care is crucial, and the absence of a physician visit after discharge may be an influencing factor in the rehospitalization of patients. A survey of Medicare claims data from approximately 12 million beneficiaries reported that most patients with a medical disorder who were rehospitalized within 30 days did not appear to have completed a follow-up visit with an outpatient physician after discharge [Citation15]. The GOLD report recommends that patients who are hospitalized with a COPD exacerbation be followed up by an outpatient physician within 4 or 12 weeks as required [Citation1]. Hospitalists may need to guide case managers and patients in tailoring the timing and frequency of follow-up visits according to risk of recurrent exacerbations. Health care providers involved in acute patient care could help hospitalists and case managers maintain continuity of communication. For instance, patients who received follow-up phone calls from pharmacists involved in the care of hospitalized patients have demonstrated fewer visits to the emergency department and fewer readmissions because medication-related problems were resolved [Citation90]. Similarly, follow-up phone calls from nurses within 72 hours of discharge resulted in reduced readmissions [Citation91]. For patients requiring end-of-life care, the palliative care team should ensure patients are referred to an appropriate care facility or home care services, taking into consideration patient/caregiver preferences [Citation79]. A postdischarge COPD algorithm is proposed in .

7. Conclusions

Identification of the underlying cause of COPD exacerbation and assessment of its severity is fundamental to guiding management. Multifaceted disease management and care transitions managed by hospitalists can increase the quality of COPD care by potentially reducing patient readmissions and their associated costs. Predischarge and postdischarge plans should be multidisciplinary in approach, involving a hospitalist and inpatient case manager who coordinate the inpatient and outpatient health care teams to ensure the seamless transition of patients with COPD across care settings.

A concise discharge plan will decrease symptom burden, contribute to a faster recovery, increase the patient’s quality of life, and prevent or reduce future exacerbations. Emphasis should be placed on patient education in terms of the correct use of inhalation delivery devices, smoking cessation, recognizing early signs of COPD exacerbations, obtaining care promptly in the case of a new exacerbation, and the importance of attending follow-up appointments after a hospital admission. The implementation of written and verbal communication to help the transition of care may ensure that care after discharge minimizes the risk of readmission.

Disclosure of financial/other conflicts of interest

ANA reported serving as principal investigator or co-investigator of clinical trials sponsored by Alexion, Blade Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Fulcrum Therapeutics, Humanigen, NeuroRx Pharma, NIH/NIAID, Novartis, OctaPharma, PTC Therapeutics, Pulmotect, and Takeda. He has served as speaker and/or consultant for Achogen, Alexion, Aseptiscope, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferring, HeartRite, LaJolla, Millenium, Mylan/Theravance Biopharma, Nabriva, Novartis, Paratek, PeraHealth, Pfizer, Portola, Salix, Sprightly, Sunovion, and Tetraphase. He has not received any payment for this manuscript.

SC is currently compensated by Boehringer Ingelheim for lectures relating to peak inspiratory flow rate. She has not received any payment for this manuscript.

JAW currently sits on the Boehringer Ingelheim’s Speakers’ Bureau. He has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim (in the past 12 months) and has served as a consultant for Theravance Biopharma (December 2018). He has not received any payment for this manuscript.

NAH has received honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, GSK, Mylan, Novartis, Sanofi, Teva, and Theravance Biopharma. His institution has received research grant support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, Gossamer Bio, GSK, Novartis, and Sanofi. He has not received any payment for this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Gráinne Faherty, MPharm, for medical writing and Frederique H. Evans, MBS, for editorial assistance (both from Ashfield MedComms, an Ashfield Health Company) in the preparation of the manuscript. Medical writing support was funded by Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA, USA) and Mylan, Inc., a Viatris Company (Canonsburg, PA, USA).

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstuctive pulmonary disease (2021 report). 2021 cited Jan 26 2021. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf

- American Lung Association. How serious is COPD. 2019 cited Jan 26 2021. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/copd/learn-about-copd/how-serious-is-copd.html

- World Health Organization. COPD predicted to be third leading cause of death in 2030. 2008 cited Jan 26 2021. https://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/World_Health_Statistics_2008/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics Reports. Final Data for 2017, cited January 26 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_09-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COPD. cited Jan 26 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/dotw/copd/index.html

- Mathers C, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442.

- Kohansal R, Martinez-Camblor P, Agustí A, et al. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction revisited: an analysis of the Framingham offspring cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):3–10.

- Eisner M, Anthonisen N, Coultas D, et al. An official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):693–718.

- Salvi S, Barnes P. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;14(9691):733–743.

- Make B, Dutro M, Paulose-Ram R, et al. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1–9.

- Lindenauer P, Pekow P, Gao S, et al. Quality of care for patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):894–903.

- O’Donnell D, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(suppl b):5B–32B.

- Anzueto A, Leimer I, Kesten S. Impact of frequency of COPD exacerbations on pulmonary function, health status and clinical outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:245–251.

- Soler-Cataluña J, Martínez-García M, Román Sánchez P, et al. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–931.

- Jencks S, Williams M, Coleman E. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132(6):1748–1755.

- Shah T, Press V, Huisingh-Scheetz M, et al. COPD readmissions: addressing COPD in the era of value-based health care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916–926.

- Ford E, Murphy L, Khavjou O, et al. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged ≥18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147(1):31–45.

- Han M, Martinez C, Au D, et al. Meeting the challenge of COPD care delivery in the USA: a multiprovider perspective. Lancet. 2016;4(6):473–526.

- Mannino D. Counting costs in COPD from the Department of Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health, University of Kentucky College of Public Health: what do the numbers mean? Chest. 2015;147(1):3–5.

- Chuang C. Transition of patients with COPD across different care settings: challenges and opportunities for hospitalists. Hosp Pract. 2012;40(1):176–185.

- Chuang C, Levine SH, Rich J. Enhancing cost-effective care with a patient-centric coronary obstructive pulmonary disease program. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14(3):133–136.

- Dewan N, Rice K, Caldwell M, et al. Economic evaluation of a disease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2011;8(3):153–159.

- Koff P, Jones R, Cashman J, et al. Proactive integrated care improves quality of life in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1031–1038.

- Nici L, ZuWallack R. Integrated care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and rehabilitation. COPD. 2018;15(3):223–230.

- Qureshi H, Sharafkhaneh A, Hanania N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5(5):212–227.

- Miravitlles M, Moragas A, Hernández S, et al. Is it possible to identify exacerbations of mild to moderate COPD that do not require antibiotic treatment? Chest. 2013;144(5):1571–1577.

- Beghé B, Verduri A, Roca M, et al. Exacerbation of respiratory symptoms in COPD patients may not be exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(4):993–995.

- Blackstock F, ZuWallack R, Nici L, et al. Why don’t our patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease listen to us? The enigma of nonadherence. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(3):317–323.

- Loh C, Peters S, Lovings T, et al. Suboptimal inspiratory flow rates are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and all-cause readmissions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(8):1305–1311.

- Celli B, MacNee W, Agusti A. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–946.

- Crisafulli E, Barbeta E, Ielpo A, et al. Management of severe acute exacerbations of COPD: an updated narrative review. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2018;13(1):36.

- Cazzola M, Bettoncelli G, Sessa E, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80(2):112–119.

- Rutten F, Cramer M, Lammers J, et al. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an ignored combination? Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8(7):706–711.

- Batterink J, Dahri K, Aulakh A, et al. Evaluation of the use of inhaled medications by hospital inpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2012;65(2):111–118.

- Press V, Arora V, Shah L, et al. Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):635–642.

- Taffet G, Donohue J, Altman P. Considerations for managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:23–30.

- Yawn B, Colice G, Hodder R. Practical aspects of inhaler use in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the primary care setting. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:495–502.

- Bourbeau J, Bartlett S. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax. 2008;63(9):831–838.

- Lindenauer P, Shieh M, Pekow P, et al. Use and outcomes associated with long-acting bronchodilators among patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(8):1186–1194.

- Petite S, Murphy J. Evaluation of bronchodilator use during chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation inpatient admissions. Hosp Pharm. 2019;54(2):112–118.

- Walters J, Tan D, White C, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1(9):CD001288.

- Leuppi J, Schuetz P, Bingisser R, et al. Short-term vs conventional glucocorticoid therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2223–2231.

- Woods J, Wheeler J, Finch C, et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:421–430.

- Lindenauer P, Pekow, P, Lahti, M, et al. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2359–2367.

- Quon B, Gan W, Sin D. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133(3):756–766.

- Vollenweider D, Jarrett H, Steurer-Stey C, et al. Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD010257.

- El Moussaoui R, Roede B, Speelman P, et al. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63(5):415–422.

- Falagas M, Avgeri S, Matthaiou D, et al. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(3):442–450.

- Miravitlles M, Anzueto A. Chronic respiratory infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what is the role of antibiotics? Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1344.

- Rello J. Importance of appropriate initial antibiotic therapy and de-escalation in the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia. Eur Respir Rev. 2007;16(103):33–39.

- Nebraska Medicine. Antibiotic guidance for treatment of acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) in adults. cited Jan 26 2021. https://www.nebraskamed.com/sites/default/files/documents/for-providers/asp/COPD_pathway2018_Update.pdf

- Putcha N, Wise R. Medication regimens for managing COPD exacerbations. Respir Care. 2018;63(6):773–782.

- Sethi S. Infection as a comorbidity of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(6):1209–1215.

- Usmani O, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):10.

- Silver P, Kollef M, Clinkscale D, et al. A respiratory therapist disease management program for subjects hospitalized with COPD. Respir Care. 2017;62(1):1–9.

- Smith A, Palmer V, Farhat N, et al. Hospital-based clinical pharmacy services to improve ambulatory management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharm Technol. 2017;33(1):8–14.

- Yu A, Guérin A, Ponce de Leon D, et al. Therapy persistence and adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multiple versus single long-acting maintenance inhalers. J Med Econ. 2011;14(4):486–496.

- Sanders M. Guiding inspiratory flow: development of the In-Check DIAL G16, a tool for improving inhaler technique. Pulm Med. 2017;2017:1495867.

- Ghosh S, Pleasants R, Ohar J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rates in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:585–595.

- Janssens W, VandenBrande P, Hardeman E, et al. Inspiratory flow rates at different levels of resistance in elderly COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(1):78–83.

- Mahler D. Peak inspiratory flow rate as a criterion for dry powder inhaler use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(7):1103–1107.

- Mahler D, Waterman L, Gifford A. Prevalence and COPD phenotype for a suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rate against the simulated resistance of the Diskus® dry powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26(3):174–179.

- Sharma G, Mahler D, Mayorga V, et al. Prevalence of low peak inspiratory flow rate at discharge in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2017;4(3):217–224.

- MacNee W. Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2(4):258–266.

- Tønnesen P. Smoking cessation and COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(127):37–43.

- Kopsaftis Z, Wood-Baker R, Poole P. Influenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD002733.

- Nichols M, Andrew M, Hatchette T, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness to prevent influenza-related hospitalizations and serious outcomes in Canadian adults over the 2011/12 through 2013/14 influenza seasons: a pooled analysis from the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS Network). Vaccine. 2018;36(16):2166–2175.

- Walters J, Tang J, Poole P, et al. Pneumococcal vaccines for preventing pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD001390.

- Cornelison S, Pascual R. Pulmonary rehabilitation in the management of chronic lung disease. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(3):577–584.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–64.

- McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(2):CD003793.

- Cavaillès A, Brinchault-Rabin G, Dixmier A, et al. Comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(130):454–475.

- Chatila W, Thomashow B, Minai O, et al. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549–555.

- Finks S, Rumbak M, Self T. Treating hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):353–363.

- Morgan A, Zakeri R, Quint J. Defining the relationship between COPD and CVD: what are the implications for clinical practice? Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1753465817750524.

- Marin J, Soriano J, Carrizo S, et al. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(3):325–331.

- Yohannes A, Alexopoulos G. Depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):345–349.

- Landers A, Wiseman R, Pitama S, et al. Severe COPD and the transition to a palliative approach. Breathe (Sheff). 2017;13(4):310–316.

- Mansukhani R, Bridgeman M, Candelario D, et al. Exploring transitional care: evidence-based strategies for improving provider communication and reducing readmissions. P T. 2015;40(10):690–694.

- Jalota L, Jain V. Action plans for COPD: strategies to manage exacerbations and improve outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;2(11):1179–1188.

- Donaldson G, Wedzicha J. COPD exacerbations. 1: epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61(2):164–168.

- Gruffydd-Jones K, Langley-Johnson C, Dyer C, et al. What are the needs of patients following discharge from hospital after an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(6):363–368.

- Coleman E. The Care Transitions Program. What will it take to ensure high quality transitional care? 2011 cited Feb 10 2021. http://www.caretransitions.org

- García-Fernández F, Arrabal-Orpez M, Rodríguez-Torres Mdel C, et al. Effect of hospital case-manager nurses on the level of dependence, satisfaction and caregiver burden in patients with complex chronic disease. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19–20):2814–2821.

- Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips C, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- Pham H, Grossman J, Cohen G, et al. Hospitalists and care transitions: the divorce of inpatient and outpatient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(5):1315–1327.

- Burke R, Ryan P. Postdischarge clinics: hospitalist attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):578–581.

- Piquet J, Chavaillon J, David P, et al. High-risk patients following hospitalisation for an acute exacerbation of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(4):946–955.

- Sanchez G, Douglass M, Mancuso M. Revisiting project re-engineered discharge (RED): the impact of a pharmacist telephone intervention on hospital readmission rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):805–812.

- Harrison J, Auerbach A, Quinn K, et al. Assessing the impact of nurse post-discharge telephone calls on 30-day hospital readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1519–1525.