Abstract

The naming of places on university campuses plays an important role in shaping the cultural landscapes and geographies of higher education institutions. In recent years, there have been contentious debates over place renaming at colleges and universities in North America and around the world, which has drawn increasing attention to the politics of toponymic practices in higher education contexts. The decision-making process involved in place naming on a university’s campus is generally informed by the institution’s naming policy and implemented by a university naming committee, yet there is very little scholarship on university naming policy frameworks, procedures, and practices. In this article, we provide a systematic and comparative analysis of university naming policies in Canada and the United States. Drawing on data from more than 2,000 colleges and universities across North America, we assess the level of representation that faculty and students have on university naming committees, institutional commitments to public engagement in the naming process, the value of diversity, and restrictions on corporate naming rights agreements. We conclude that colleges and universities should develop more inclusive and equitable naming policy frameworks to ensure that campus namescapes live up to the ideals of higher education institutions in the twenty-first century.

在塑造高等教育机构的文化景观和地理环境方面, 大学校园场所的命名发挥着重要作用。近年来, 在北美和世界各地的学院和大学中, 场所重新命名一直存在争议, 引起了人们对高等教育地名行为政治的日益关注。大学校园场所命名的决策过程, 通常由学校的命名政策决定, 并由大学命名委员会实施。但是, 文献很少研究大学命名政策的框架、程序和实践。本文对加拿大和美国的大学命名政策进行了系统性比较分析。根据北美2,000多所学院和大学的数据, 评估了教职员工和学生在大学命名委员会中的代表性、学校对公众参与命名的承诺、多样性的价值、企业命名权协议的限制。我们的结论是, 学院和大学应当制定更包容、更公平的命名政策框架, 以确保校园命名景观符合21世纪高等教育机构的理念。

Asignar nombres a los lugares de los recintos o campus universitarios juega un papel importante en la configuración de los paisajes culturales y las geografías de instituciones de educación superior. En años recientes, se han presentado polémicos debates sobre el cambio de nombres en las instituciones de educación superior y en las universidades de Norteamérica y alrededor del mundo, lo cual ha atraído mayor atención a las políticas de las prácticas toponímicas, en contextos universitarios. El proceso de toma de decisiones asociado con la nomenclatura de un recinto universitario generalmente va de la mano de las políticas que al respecto siga la universidad, cuya implementación corre de cuenta del comité de nomenclatura de lugares, aunque en verdad es escasa la erudición que informa los enfoques que se aplican por tales comités, sus procedimientos y prácticas. En este artículo, presentamos un análisis sistemático y comparativo de las políticas de designación de nombres para los lugares de los campus universitarios en Canadá y Estados Unidos. A partir de los datos de más de 2.000 institutos de educación superior y universidades, a lo largo y ancho de Norteamérica, evaluamos el nivel de representación que tienen los profesores y estudiantes en los comités establecidos para asignar aquellas denominaciones, los compromisos institucionales con la participación pública en esos procesos, el valor de la diversidad y las restricciones a los acuerdos de derechos sobre designaciones corporativas. Concluimos que los institutos de educación superior y las universidades deben desarrollar unos marcos de políticas sobre este tipo de nomenclaturas, más incluyentes y equitativos, para garantizar que el paisaje de nombres de lugares en el campus esté a la altura de los ideales de las entidades de educación superior en el siglo XXI.

On 26 April 2022, it was announced that Ryerson University would be renamed Toronto Metropolitan University after years of student activism calling for the name change (CBC News Citation2022). During the nineteenth century, Egerton Ryerson played a leading role in the establishment of Canada’s residential school system, which forcibly removed Indigenous children from their families and placed them in boarding schools where they were subjected to assimilationist ideologies, physical and sexual abuse, and, in numerous cases, premature death. In response to activist efforts to rename the university and remove a statue of Ryerson from campus, university leaders added a historical plaque next to the statue in 2018 that acknowledged Ryerson’s role in creating the residential school system as a form of cultural genocide (Alozzi Citation2018). Yet, following the discovery of unmarked graves of Indigenous children at the Kamloops Residential School in British Columbia in May 2021, and related efforts at former residential school sites across the country, calls to rename places and remove statues honoring the champions of settler colonialism in Canada acquired a growing sense of urgency. Within this context, the Ryerson statue on the university’s campus was torn down by protesters in June 2021, and, over the course of the next year, a university task force developed a series of recommendations, the most significant of which was to rename the university itself, which eventually occurred in 2022 (DiSaia, Ellis, and Dallaire Citation2023).

The renaming of places and the removal of statues and monuments have become major focal points of political action, controversy, and conflict over the past decade (Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2022; Carlson and Farrelly Citation2023; Gensburger and Wüstenberg Citation2023). Commemorative place names have long served to inscribe the ideology of those with social, political, and economic power into the cultural landscape, thereby entrenching a particular conception of historical memory in the spaces of everyday life. The act of place renaming is therefore a key strategy for reckoning with the historical legacies of racial, gender, and class inequalities as well as the genocidal policies of settler colonialism, all of which continue to shape contemporary life in the twenty-first century.

Over the past several decades, geographers and other scholars have made important contributions to the field of critical toponymies, or the critical study of place naming (Berg and Vuolteenaho Citation2009; Rose-Redwood, Alderman, and Azaryahu Citation2010, Citation2018; Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch Citation2016, Citation2022; Bigon and Zuvalinyenga Citation2021; Rusu Citation2021; Gnatiuk and Basik Citation2023). Recent works have begun to consider how the namescape of the university campus has itself become an important arena of memory politics (Brophy Citation2010; Brasher, Alderman, and Inwood Citation2017; Alderman and Rose-Redwood Citation2020; DiSaia, Ellis, and Dallaire Citation2023). When petitions to rename a campus building are proposed, they are typically considered by a university’s naming committee and ultimately its board of governors. Higher education institutions often have naming policies that provide guidelines for the naming of buildings and other places on their campuses, yet few studies have investigated university naming policies and the crucial role that they play in the making of the campus namescape.

This study provides a systematic analysis of naming policies at colleges and universities in Canada and the United States with the aim of investigating the administrative logics, practices, and procedures encountered by those seeking to transform the campus namescape. Following an overview of scholarship on the politics of place naming with a specific focus on the higher education campus as a commemorative landscape, we then discuss the data and methods employed for this study and present the key findings of our comparative analysis to illustrate how university naming policies shape the decision-making process of campus place naming. We conclude by proposing recommendations for improving university naming policies to work toward creating more inclusive and equitable decision-making processes to reshape the campus namescape and thereby transform the geographies of higher education.

The Politics of Place Naming and the University Campus as a Commemorative Landscape

Traditionally, place name scholars spent a significant amount of time tracing the historical and linguistic origins and meanings of toponyms, treating them largely as specimens or artifacts (Wright Citation1929). This conventional approach to toponymy has a long history and played an important role within the context of European colonial expansion as anthropologists, geographers, and other scholars sought to document the knowledges of peoples and places to advance the project of European colonialism.Footnote1

Recent critical retheorizations of the field have moved away from simply analyzing the names of places in and of themselves to examining the larger social, political, and economic contexts and consequences of place naming as well as more fully understanding the locational politics of how and where toponyms are emplaced and experienced within cultural landscapes (Rose-Redwood, Alderman, and Azaryahu Citation2010; Mamvura Citation2020; Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch Citation2022). The power of place naming is evident in more than just producing an isolated memorial or linguistic symbol but in how toponymies work through social actors, contested histories, policies, and lived places to form the broader namescapes that structure people’s sense of place and the past as well as their daily spatial interactions (Alderman Citation2022). Thus, it is important to recognize that educational namescapes—like all place-naming practices—“are positioned within and emerge from immediate physical, symbolic, and social settings and situated within broader environments, patterns, movements, and inequalities” (Brasher and Alderman Citation2023, 313).

More recent place-naming studies also take a decidedly more processual approach (Giraut and Houssay-Holzschuch Citation2016), moving toward an analysis of the naming process and how certain place names come into being, who is in control (or not) of naming practices, whose lived experiences are written into (and out of) the naming process, and the always emergent discursive and material work that naming performs (Wideman and Masuda Citation2018). Although the control of language and place identity, especially in highly visible settings, is central to political authority, the naming process is also open to subaltern efforts to claim long-denied rights to public spaces and self-determination. Yet the process of naming places cannot be easily reduced to this elite–marginalized binary. Rather, a wide range of tensions, needs, and intersectional identities can converge and conflict in the naming process (Rose-Redwood Citation2008). As Brasher (Citation2023) observed of many higher education toponymic debates, elite and marginalized groups on campuses are anything but monolithic. He added that the symbolic capital accrued through the (re)naming of university places can often be coopted and reappropriated to serve different interests—such as when university officials remove controversial place names to placate without really meeting the demands of those oppressed by the landscape symbol.

Scholars have thus increasingly theorized place naming as a technology of power—that is, a means of ordering, controlling, and resisting the identities of both places and people as shaped by broader distributions of power, access, and rights within society (Rose-Redwood, Alderman, and Azaryahu Citation2018). Place naming participates in the social construction of identity across a broad range of geographical scales and political settings—from serving as a tool of nationalism, regime change, and geopolitics (Hui Citation2019; Azaryahu Citation2020; Gnatiuk and Basik Citation2023; Sysiö, Ülker, and Tokgöz Citation2023) to being deployed in the service of the marketing and commodification of place (Madden Citation2018; Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2019). Important to our purposes here, the naming of places is heavily involved in the politics of public commemoration and therefore calls on us to consider the power of toponymies to selectively remember (or forget) historical narratives and identities in ways that can work to reinforce sociospatial exclusion or to articulate more inclusive connections between people, places, and the past (Alderman and Inwood Citation2013).

Building on the work of Alderman (Citation2002), critical toponymic scholarship increasingly recognizes the strong memorialization dynamics at play through educational namescapes, not just at universities but also at primary and secondary schools. Indeed, K–12 public schools in Canada and the United States have seen numerous highly charged calls to remove the names of racist and colonial historical figures, with even young students pushing to have a voice in the naming and commemorating process (Mitchell Citation2020; Hernandez Citation2021). Both within and beyond North America, educational institutions are deeply involved in crafting and debating memory and identity at national and local community levels. They have used school names and naming policies to enact (or silence) certain pantheons of heroes and, in doing so, aim to regulate the social values and ideas internalized by students (Rusu Citation2019; da Costa Citation2022). Thus, the educational namescape itself functions as a “hidden curriculum” instructing campus communities in whose lives, historical experiences, and struggles matter (or not) within the public symbols of education and the wider social world (Alderman and Rose-Redwood Citation2020).

Commemoratively named places not only engage in a direct narration of memory but also create what Sumartojo (Citation2016) called “commemorative atmospheres,” which work with sensory and social experiences, individual memory, and the built environment to affect people’s connections with the past and broader feelings of belonging or alienation. As Ferguson (Citation2019) argued, the names attached to educational institutions—especially those that reference racist historical figures—have the capacity to perpetuate environmental microaggressions, communicating daily place-based indignities toward teachers and students of color, and thus reinforce institutional discrimination. The affective atmosphere of place naming is especially evident in higher education institutions, where some minoritized communities of color see a direct tie between the hostile atmosphere created by campus namescapes that valorize white supremacist male figures and the fact that most universities have failed to come to terms with their historical and ongoing complicity in perpetuating racism, colonization, and patriarchy (Wilder Citation2013). Drawing on Till’s (Citation2012) influential scholarship, scholars have conceptualized universities as “wounded places” and interpreted campus place name reform as part of the “memory-work” of not only removing offensive names from the landscape but also creating new geographies of naming and memory-making that advance the politics of recognizing previously erased Indigenous ties to land and the neglected struggles of people of color, women, and queer communities (Brasher, Alderman, and Inwood Citation2017). This memory-work, as Sheehan (Citation2019) argued, is crucial to achieving “regenerative memorialization,” which stresses the healing possibilities and sociospatial justice capacities of university campus landscapes and ensures that these landscapes are responsive and evolving sociocultural systems. In the U.S. context, such practices of regenerative memorialization are part of a broader reparations movement as colleges and universities reckon with their historical ties to slavery (Moscufo Citation2022; see also Garibay, Mathis, and West Citation2022).

Any number of theoretical approaches can be applied to studying the cultural politics of naming places on university campuses, but a particularly relevant one in the case of this study is viewing naming as a cultural “arena” (Alderman and Inwood Citation2013; Basik Citation2022). The arena metaphor directs attention to the power-laden and often uneven debates and negotiations that surround naming. Examining the place-naming process as an arena of memory politics recognizes the often contentious nature of these debates as social actors and groups with varying subjectivities and histories seek to influence collective decisions, justify their naming claims, and entice others to participate in the debate. Conceiving of the university campus as an arena of cultural politics brings a heightened interest in understanding how the inscription of geographical spaces is invariably shaped by administrative policies and procedures (Azaryahu Citation1997), which determine how naming decisions are made, who holds the right to make those decisions, whose voices are included and excluded from the process, and how open naming politics is to public oversight and participation. These are centrally important ideas driving this study’s investigation.

The arena of place (re)naming debates at universities is often kept decidedly narrow and, in many cases, hidden. The confidential nature of such deliberations is, of course, not unique to university naming procedures alone but rather extends to a wide range of different governance arenas both within higher education and beyond as part of what Mulgan (Citation2014) referred to as “the private space of internal decision-making, where views are exchanged in confidence within a trusted inner circle of advisers” (84–85). In the case of campus place (re)naming, decisions are often tightly controlled by university officials and trustees, heavily influenced by donors (Krucoff Citation2021), and particularly opaque with regard to public participation—despite most institutions’ stated commitment to shared governance. Our interest in researching university naming policies is driven in part by a recognition of the procedural injustices that characterize and affect the place-naming process. Procedural justice, which has received limited attention in the field of critical toponymies (but see Alderman and Inwood Citation2013), recognizes that inclusivity in place naming is not just marked by who or what is remembered through a named place, but also whether the right to participate in decision-making processes and procedures has been realized—especially for those social groups that have been historically disenfranchised from the production of space. It is hoped that this study’s analysis can be an important first step to understanding the procedural and participatory justice obstacles shaping university place (re)naming.

Although commemoratively named campus buildings, streets, and other public spaces sit right outside many of our office doors and windows, scholars have until recently largely neglected the study of university naming practices. As of late, however, university faculty and students have played active roles in not just studying oppressive educational namescapes but also pushing for their replacement, and some geographers have taken visible stands against long-standing, racist campus monikers such as those at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill (Menefee Citation2018), Middle Tennessee State University (Allen and Brasher Citation2019), and the University of Victoria (Rose-Redwood Citation2016). Alderman and Rose-Redwood (Citation2020) sought to use these calls for name reform on university campuses as an educational moment for students to develop a keener understanding of the material, affective, and even violent capacities of place naming as well as to critically examine naming policies at their universities in terms of inclusiveness, level of public participation, and efficacy in reforming unjust commemoration. In the absence of procedural frameworks aligned with a commitment to sociospatial justice, they suggested that students might be taken through the scenario of writing their own place-naming policy for their school or university. Ensuring a robust level of publicness and responsiveness in the university naming process—especially with regard to listening to and working with the groups most oppressed by offensive names—is a key part of place renaming to serve reparative ends.

Data and Methods

This study employs both content analysis and an interpretive approach to examine the policies of place naming on university campuses. The research team collected data on university naming policies by compiling a list of liberal arts colleges and universities in Canada and the United States in 2015 based on various sources and then proceeded to conduct keyword searches online to access naming policy documents and related information for each institution, updating the list of university naming policies through to 2020.Footnote2 For the sake of convenience, we use the phrase “university naming policies” to refer to naming policies at both liberal arts colleges and universities.

In cases where we could not access a naming policy online, a member of the research team contacted university staff to request a copy of their naming policy if such a policy existed. In total, data were collected for 106 higher education institutions in Canada and 2,158 colleges and universities in the United States, or a combined total of 2,264 schools. For each college or university, the first question we considered was whether the institution had a publicly accessible naming policy. In cases where a naming policy could be identified, the research team analyzed each policy document with respect to (1) faculty and student representation in decision-making, (2) the role of public consultation in the naming process, (3) a recognition of the value of diversity in campus place naming, and (4) any restrictions on corporate sponsorship of naming rights. In addition to the analysis of naming policy documents, the research team also examined the number of Canadian and U.S. colleges and universities that had experienced at least one naming controversy.

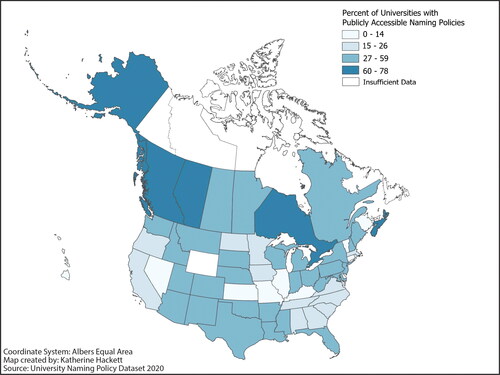

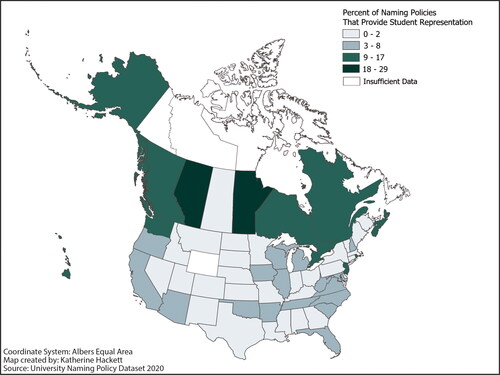

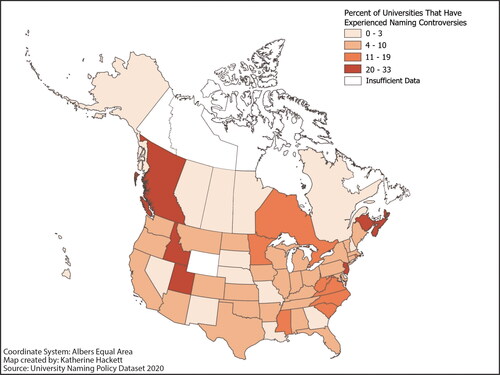

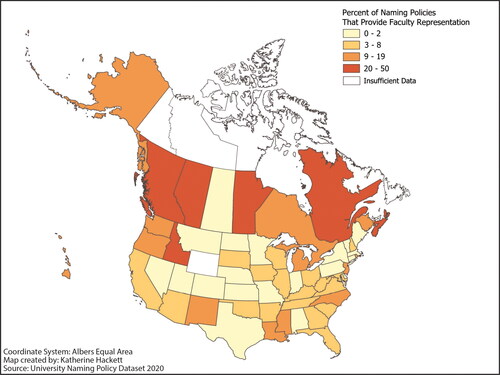

Following the data collection process, the research team tabulated and mapped the results and compared the findings for Canada and the United States, which are presented in the next section. Several Canadian provinces and territories (Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nunavut, and the Yukon) and one U.S. state (Wyoming) had insufficient data for the purposes of calculating province- or state-wide percentages (e.g., calculating a percentage with either no data or only one data point), so we have listed these with the label of “insufficient data” when mapping the research findings (). We also developed a Web map using ESRI’s ArcGIS Online software, which is publicly accessible as an online resource for university administrators, faculty, staff, students, and researchers (Hackett and Rose-Redwood Citation2020).

Figure 2 Universities that provide faculty representation in naming decisions in Canada and the United States.

A Comparative Analysis of University Naming Policies in Canada and the United States

Naming policies provide an institutional framework to guide decision-making related to the naming of new buildings and other places, as well as the renaming of existing places, on university campuses. Of the 2,264 higher education institutions in Canada and the United States considered in this study, 620 schools (27.4 percent) had a publicly accessible naming policy (see ; ). This figure was significantly higher in Canada (58.5 percent), however, compared to the United States (25.9 percent).

Table 1 Summary assessment of university naming policies in Canada and the United States, c. 2020

One indicator of the inclusivity of a university’s naming policy is whether faculty and students have formal representation to serve on naming committees and thus have a seat at the table when campus naming decisions are made. In this respect, our research findings indicate that Canadian universities with naming policies were more inclusive of both faculty and student representation compared to their U.S. counterparts. More specifically, half of all Canadian universities with naming policies included faculty representation on naming committees, whereas only 15.8 percent of U.S. university naming policies had a similar requirement (). The data are less encouraging when it comes to student representation, with 21.0 percent of Canadian university naming policies including a student representative on naming committees and only 9.9 percent of naming policies in the United States requiring student representation (). When considering Canada and the United States together, a total of 19.2 percent of university naming policies provided faculty representation and 11.0 percent included student representation. Faculty and students are key constituencies within the university community, and making space for their inclusion in the decision-making process for campus place naming signals that their voices are valued as active participants in the making of the campus environment. In contrast, excluding faculty and students from university naming committees sends a message to the university community that campus place naming is strictly the purview of university administrators and appointed officials as part of a top-down decision-making process.

Although the internal deliberations of university naming committees are generally confidential, some university naming policies allow for different forms of public consultation to inform the committee’s work. In Canada, 17.7 percent of universities with naming policies provided an opportunity for public consultation related to at least some aspect of campus name changes, and the figure was even lower among higher education institutions in the United States (3.9 percent). The lack of public consultation over campus naming is a missed opportunity to build a shared sense of community through the making of the campus as a commemorative landscape.

Examples of policy language related to public consultation that could serve as models for other university naming policies can be found in both Canada and the United States. For instance, the naming policy at Carleton University in Ottawa states that “[c]oncerns from any member of the Carleton community regarding a philanthropic naming opportunity may be submitted” (Carleton University Citation2021). Similarly, California State University at Los Angeles has a policy statement noting that “[a]rguments in support of or opposition to the proposal may be submitted by individuals, organizational units, and any interested person(s)” (California State University–Los Angeles Citation2007). This implies, however, that the university community is aware of a naming proposal, yet many proposals are submitted to naming committees confidentially without the knowledge of the university community as a whole. Although many naming proposals remain confidential until they are approved, there are some cases in which members of the university community petition the administration to rename a building that has a controversial name. In such cases, a naming proposal might become an issue of public debate on campus. Whether a naming proposal is confidential or public knowledge, outlining a process for seeking input from relevant stakeholders in university naming policies is an important way for universities to demonstrate their commitment to engaging in meaningful consultation with the university community on matters of public concern.

The inclusion of more diverse voices in the discussion over campus place naming could lead to a greater recognition of the need to diversify the campus namescape itself. As of 2020, however, only 3.2 percent of Canadian and 1.8 percent of U.S. universities with naming policies included any mention of the importance of “diversity” in their naming policy. Most university naming policies view each naming opportunity in isolation rather than considering how they relate to the broader toponymic pattern of the campus namescape. Exceptions include schools such as Humboldt State University and California State University at East Bay. Both cases acknowledge the importance of social and cultural diversity more generally, noting that campus naming should involve:

recognizing cultural, ethnic, national, and gender diversity with fairness, dignity, compassion, and procedural consistency. (Humboldt State University Citation2005)

[s]pecial attention … to the desirability of achieving over the long run a pattern of names that will reflect the ethnic and gender diversity of the California society CSUEB serves. (California State University–East Bay Citation2009)

Many building names on university campuses are named in honor of wealthy donors and increasingly corporate sponsors as well. A number of higher education institutions, however, have restrictions on the corporate sponsorship of naming rights. By our estimate, 56.5 percent of Canadian universities and 25.6 percent of U.S. universities with naming policies have some form of restrictions on corporate naming. For instance, Indiana University at Bloomington has a firm policy against naming academic buildings and entities after corporate sponsors, with its naming policy stating that “[m]ajor academic facilities and major academic organizations should be permanently named for individuals and not for corporate entities” (Indiana University–Bloomington Citation2021). The naming policy of McGill University in Montreal similarly requires that “[b]uildings and academic units and programs shall be named only after individuals” (McGill University Citation2019), and, thus, not after corporate sponsors.

The distinction between the corporate naming of academic and nonacademic buildings is made particularly clear in the University of Texas System’s policy, which notes that “[c]orporate namings for academic and health buildings, colleges and schools, and academic departments shall not occur, with the exception of rare and special circumstances,” while allowing for the corporate naming of “athletics facilities, arts facilities, and museums, conference centers, and non-academic and non-health facilities” (University of Texas System Citation2021). By contrast, other higher education institutions do not permit corporate naming for any university buildings. As the naming policy for Fairmont State University in West Virginia makes clear, “Corporate names are not considered to be appropriate for the external identification of campus buildings” (Fairmont State University Citation2008). Some higher education institutions that do allow for the corporate naming of campus buildings place restrictions on the type of corporate sponsorships that are permitted. For example, Nicholls State University in Louisiana requires that the “university will not consider the names of companies associated with the production or sale of tobacco products, arms producers, or alcoholic beverages” (Nicholls State University Citationn.d.). Other universities place restrictions on the use of corporate logos in campus signage (e.g., University of California System Citation2002). The selling of naming rights for campus buildings to corporate sponsors is part of a broader trend toward the corporatization of public namescapes globally (Light and Young Citation2015; Rose-Redwood et al. Citation2019), which comes with the opportunity costs of privileging the interests of those with economic capital over efforts to produce a more equitable commemorative landscape that recognizes members of the university community irrespective of their wealth and power.

In addition to the analysis of university naming policies, the research team also documented naming controversies at higher education institutions. Based on our findings, as of 2020, approximately 15.1 percent of universities in Canada had experienced at least one naming controversy and 6.9 percent of higher education institutions in the United States had become embroiled in a debate over campus place naming (). In total, around 7.3 percent of universities in Canada and the United States combined had experienced such a toponymic debate over a renaming on campus. In Canada, the greatest total number of universities that had experienced a naming controversy were located in Ontario (six), followed by British Columbia (three), Nova Scotia (three), New Brunswick (two), and Newfoundland and Laborador (one). Among U.S. universities, campus naming controversies were most evident in Pennsylvania (fourteen) and California (ten), followed by New Jersey (eight), Texas (eight), Minnesota (seven), North Carolina (seven), Virginia (seven), and various other states. Such naming controversies have generally involved calls to rename a building that honors a historical figure with ties to white supremacy, slavery, settler colonialism, or a controversial corporate sponsor. Student activism has often played an important role in campus renaming efforts, and, as the demand for social justice grows, the number of naming controversies on university campuses will likely continue to increase in the future.

Conclusion

College and university campuses are key spaces in which higher education institutions express their values in both material and symbolic terms. The naming of campus buildings and other places is an important arena through which such values are articulated, publicly recognized, and institutionally maintained. As such, the campus namescape is an integral part of the “hidden curriculum” of higher education. It therefore deserves greater attention from the academic community (Alderman and Rose-Redwood Citation2020). In this article, we have highlighted the role that university naming policies play in shaping the institutional frameworks that inform the campus naming process with respect to decision-making, stakeholder representation, public consultation, the value of diversity, and corporate influence over the naming process, as well as documenting the geographies of place naming controversies on university campuses in Canada and the United States. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically examines university naming policies as technologies of institutional power.Footnote3 The results of this study point toward a number of policy recommendations that we believe will make university naming policies more inclusive, equitable, and responsive to the university community, which we outline next.

Recommendation 1: Ensure That Key Stakeholders Such as Faculty and Students Have Representation on University Naming Committees

Given the importance of the campus namescape to the university community as a whole, it is critical that diverse stakeholders are included in the decision-making process related to campus naming practices. In addition to university administrators, donor relations, facilities management, and so on, other stakeholders such as faculty and students should also be included as official members of a university’s naming committee. Faculty and students are the largest constituents on a university campus and are the primary users of campus place names for wayfinding purposes as they navigate throughout the campus landscape on an everyday basis. They are also generally attentive to how existing campus place names are perceived by the university community and what type of reception a proposed place name would likely receive if adopted. Moreover, students have often played a leading role in calling attention to inequities in the campus namescape. If higher education institutions are truly committed to creating a sense of belonging within the university community, the inclusion of faculty and students on naming committees can contribute to identifying gaps and areas of improvement to foster a more inclusive campus environment.

Recommendation 2: Incorporate Meaningful Opportunities for Public Consultation as Part of the Standard Procedures of Campus Place Naming

Campus place-naming decisions are generally made by university naming committees through a confidential process and, thus, the university community often only learns of a new name once the decision has already been made. In many cases, there are good reasons to maintain confidentiality in the naming process, particularly when it involves negotiations with potential donors. A lack of transparency in the decision-making process, however, can result in a loss of trust and a feeling of disempowerment within the university community. We therefore recommend that university naming policies incorporate different forms of public consultation as part of the campus naming process. In cases where confidentiality must be maintained, a university naming committee should develop a process for engaging key stakeholder groups through private discussions that are held in confidence by all parties. For naming proposals that involve a matter of significant public concern, however, such as a petition to rename a building that honors a historical figure with a highly questionable legacy, university naming policies should clearly outline a process of public consultation with the university community, which could include a public forum or other opportunities for students, faculty, and staff to share their views of the proposed name change.

Recommendation 3: Conduct a Campus Place Name Audit and Develop a Systemic Approach to Reviewing How Individual Naming Proposals Relate to the Campus Namescape as a Whole

The vast majority of campus naming decisions are made without due consideration for how an individual naming proposal relates to the broader pattern of names that forms the campus namescape as a whole. The first step in addressing this issue is to conduct a campus place name audit, which consists of compiling a list of all place names on campus (building names, street names, etc.) and evaluating gaps, imbalances, and inequities in the university’s toponymic landscape (for a critical discussion of heritage landscape audits, see D’Ignazio, So, and Ntim-Addae Citation2022). Once this baseline assessment has been conducted, the university naming committee should engage with the university community to develop a strategic action plan for how to create a more inclusive and equitable campus namescape that aligns with the mission and values of the university.

The critical reevaluation of the campus namescape and naming process is a concrete step that higher education institutions can take to enhance the campus environment and foster a greater sense of belonging within the university community. Creating a more inclusive and equitable university naming policy framework demands bold and courageous leadership and a willingness to rethink long-standing institutional norms that have upheld social hierarchies and legacies of historical injustice. When leaders of Ryerson University announced that the university would be renamed Toronto Metropolitan University in 2022, such a move only occurred after years of student activism in the face of institutional inertia and half-measures that had largely reinforced the status quo. As Ryerson’s leaders learned the hard way, the naming of places on university campuses—and the naming of universities themselves—matters and can have consequential effects for the very identity of a higher education institution and the members of its community. Developing a university naming policy that represents the voices of key stakeholders, provides opportunities for meaningful public consultation, and adopts a systemic approach to campus place naming can lay the groundwork for creating a campus environment that lives up to the ideals of higher education institutions in the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the constructive feedback from the anonymous peer reviewers of this article and the journal’s editor, Heejun Chang. We would also like to acknowledge the numerous undergraduate and graduate research assistants who contributed to the data collection process for this research project, including Spencer Bradbury, Helena Andrade, Alison Root, Tyler Blackman, Maggy Spence, Justin Poon, Teegan Macdonald, Lucas Aubert, and Katherine Hackett.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Reuben Rose-Redwood

REUBEN ROSE-REDWOOD is a Professor in the Department of Geography and Associate Dean of Academic in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Victoria, Victoria, BC V8W 2Y2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include cultural landscape studies, critical toponymies, memory studies, and the spatial histories of geocoded worlds.

CindyAnn Rose-Redwood

CINDYANN ROSE-REDWOOD is an Associate Teaching Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria, Victoria, BC V8W 2Y2, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include the social and political experiences of international students in higher education settings, the social geographies of immigrant communities in North American cities, and the Caribbean diaspora.

Derek H. Alderman

DEREK H. ALDERMAN is a Professor in the Department of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include race, public memory, social justice, and critical toponymies. He currently serves on the first U.S. Federal Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names.

Katherine Hackett

KATHERINE HACKETT is an Independent Scholar in Victoria, BC, Canada. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include spatial analysis and visualizing data through interactive maps.

Notes

1 Despite the colonial erasure of Indigenous place names from maps during the colonization process, Indigenous scholars and communities have themselves engaged in efforts to document and reclaim Indigenous toponymies (e.g., Gray and Rück Citation2019).

2 A team of research assistants was given a common set of instructions for data collection. In some cases, though, there were minor inconsistencies in the way that each research assistant coded the naming policy data that they entered into the database. To address this issue, when new research assistants were brought onto the project, they were instructed to update the data input during previous years and correct any errors or misinterpretations. It is possible, however, that human error could have resulted in missing information or misinterpretations of policy content for some higher education institutions included in the data set.

3 Keyword searches for university naming policies yielded no results in Web of Science or Google Scholar for academic works with an analysis of university naming policies as a primary focus.

Literature Cited

- Alderman, D. H. 2002. School names as cultural arenas: The naming of US public schools after Martin Luther King, Jr. Urban Geography 23 (7):601–26. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.23.7.601.

- Alderman, D. H. 2022. Commemorative place naming: To name place, to claim the past, to repair futures. In The politics of place naming: Naming the world, ed. F. Giraut and M. Houssay-Holzschuch, 29–46. London: ISTE.

- Alderman, D. H., and J. Inwood. 2013. Street naming and the politics of belonging: Spatial injustices in the toponymic commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Social & Cultural Geography 14 (2):211–33. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2012.754488.

- Alderman, D. H., and R. Rose-Redwood. 2020. The classroom as “toponymic workspace”: Towards a critical pedagogy of campus place renaming. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 44 (1):124–41. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2019.1695108.

- Allen, D., and J. P. Brasher. 2019. #ChangetheDamnName: MTSU student activism against Forrest Hall, white supremacy, and a reparative approach to heritage preservation. The Activist History Review. Accessed November 22, 2019. https://activisthistory.com/2019/11/22/changethedamnname-mtsu-student-activism-against-forrest-hall-white-supremacy-and-a-reparative-approach-to-heritage-preservation/.

- Alozzi, R. 2018. Ryerson unveils plaque recognizing its racist history. The Eyeopener. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://theeyeopener.com/2018/06/ryerson-unveils-plaque-recognizing-its-racist-history.

- Azaryahu, M. 1997. German reunification and the politics of street names: The case of East Berlin. Political Geography 16 (6):479–93. doi: 10.1016/S0962-6298(96)00053-4.

- Azaryahu, M. 2020. Name-making as place-making. In Naming, identity and tourism, ed. L. Caiazzo, R. Coates, and M. Azaryahu, 11–27. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars.

- Basik, S. 2022. Vernacular place name as a cultural arena of urban place-making and symbolic resistance in Minsk, Belarus. Urban Geography 44 (8):1825–32. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2022.2125666.

- Berg, L., and J. Vuolteenaho, eds. 2009. Critical toponymies: The contested politics of place naming. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Bigon, L., and D. Zuvalinyenga. 2021. Gendered urban toponyms in the Global South: A time for de-colonization? Urban Geography 42 (2):226–39. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2020.1825275.

- Brasher, J. P. 2023. Place (re)naming. In Re-reading the American landscape: Environments, cultures, and places, ed. C. Post, G. Buckley, and A. Greiner, 243–52. London and New York: Routledge.

- Brasher, J. P., and D. H. Alderman. 2023. From de-commemoration of names to reparative namescapes: De-commemoration: Removing statues and renaming places, ed. S. Gensburger and J. Wüstenberg, 309–18. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Brasher, J. P., D. H. Alderman, and J. F. Inwood. 2017. Applying critical race and memory studies to university place naming controversies: Toward a responsible landscape policy. Papers in Applied Geography 3 (3–4):292–307. doi: 10.1080/23754931.2017.1369892.

- Brophy, A. 2010. The law and morality of building renaming. South Texas Law Review 52:37–67.

- California State University–East Bay. 2009. Naming physical features at California State University, East Bay (CSUEB). Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.csueastbay.edu/giving/files/docs/ua/policies/naming-physical-features.pdf.

- California State University–Los Angeles. 2007. Administrative procedure: Requests to name facilities, properties, and rooms. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.calstatela.edu/sites/default/files/groups/Administration%20and%20Finance/Procedure/ap015.pdf.

- Carleton University. 2021. Philanthropic naming policy. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://carleton.ca/secretariat/wp-content/uploads/Philanthropic-Naming-Policy-2021.pdf.

- Carlson, B., and T. Farrelly, eds. 2023. The Palgrave handbook on rethinking colonial commemorations. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- CBC News. 2022. Toronto university changes name amid controversy over Canadian educator’s legacy. CBC News, April 26, 2022. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ryerson-toronto-metropolitan-university-1.6431360.

- da Costa, D. F. 2022. The exclusion of national liberation war heroes of the opposition parties in the memorial landscape: An analysis of the Angolan toponymic law. GeoJournal 88 (3):3079–92. doi: 10.1007/s10708-022-10797-z.

- D’Ignazio, C., W. So, and N. Ntim-Addae. 2022. The audit: Perils and possibilities for contesting oppression in the heritage landscape. In The Routledge handbook of architecture, urban space and politics. Vol. I: Violence, spectacle and data, ed. F. Haghighi and N. Bobic, 250–66. London and New York: Routledge.

- DiSaia, R., C. Ellis, and J. O. Dallaire. 2023. Standing strong: The renaming of Toronto Metropolitan University. In The Palgrave handbook on rethinking colonial commemorations, ed. B. Carlson and T. Farrelly, 543–55. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Fairmont State University. 2008. Policy on commemorative tributes and naming. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.fairmontstate.edu/aboutfsu/sites/default/files/bog-policies/fsu_policy_02.pdf.

- Ferguson, G. 2019. The perceptions and effects of schools’ names on Black professional educators and their students. PhD dissertation, Marshall University.

- Garibay, J., C. Mathis, and C. West. 2022. Black student views on higher education reparations at a university with an enslavement history. Race Ethnicity and Education 25 (5):607–28. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2021.2019001.

- Gensburger, S., and J. Wüstenberg, eds. 2023. De-commemoration: Removing statues and renaming places. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Giraut, F., and M. Houssay-Holzschuch. 2016. Place naming as dispositif: Toward a theoretical framework. Geopolitics 21 (1):1–21. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2015.1134493.

- Giraut, F., and M. Houssay-Holzschuch, eds. 2022. The politics of place naming: Naming the world. London: ISTE.

- Gnatiuk, O., and S. Basik. 2023. Performing geopolitics of toponymic solidarity: The case of Ukraine. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift/Norwegian Journal of Geography 77 (2):63–77. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2023.2170827.

- Gray, C., and D. Rück. 2019. Reclaiming Indigenous place names. Yellowhead Institute Policy Brief. Accessed August 18, 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2019/10/08/reclaiming-indigenous-place-names.

- Hackett, K., and R. Rose-Redwood. 2020. Geography of university place naming webmap. Victoria, BC, Canada: Critical Geographies Research Collaboratory. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://uvgeog.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=f9da0d59b6b0436585a70240dcec5b09.

- Hernandez, J. 2021. Strathcona students campaign to rename elementary school after sprinter Barbara Howard. CBC News, May 17. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/students-campaign-rename-school-after-canadian-runner-1.6027900.

- Hui, D. L. H. 2019. Geopolitics of toponymic inscription in Taiwan: Toponymic hegemony, politicking and resistance. Geopolitics 24 (4):916–43. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2017.1413644.

- Humboldt State University. 2005. Policy and procedures for naming facilities. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://policy.humboldt.edu/uml-05-01-policies-and-procedures-naming-facilities-humboldt-state-university-and-california.

- Indiana University–Bloomington. 2021. Institutional naming. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://policies.iu.edu/policies/ua-06-institutional-naming/index.html#procedures.

- Krucoff, O. 2021. Naming rights: What universities gain and lose when they name places after people. Columbia Missourian, August 22. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.columbiamissourian.com/sports/mizzou_sports/naming-rights-what-universities-gain-and-lose-when-they-name-places-after-people/article_b4e11320-e144-11eb-b936-b74ef4d0a92d.html.

- Light, D., and C. Young. 2015. Toponymy as commodity: Exploring the economic dimensions of urban place names. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (3):435–50. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12153.

- Madden, D. J. 2018. Pushed off the map: Toponymy and the politics of place in New York City. Urban Studies 55 (8):1599–1614. doi: 10.1177/0042098017700588.

- Mamvura, Z. 2020. “Let us make Zimbabwe in my own name”: Place naming and Mugabeism in Zimbabwe. South African Journal of African Languages 40 (1):32–39. doi: 10.1080/02572117.2019.1672343.

- McGill University 2019. Policy relating to the naming of university assets. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.mcgill.ca/secretariat/files/secretariat/policy_related_to_the_naming_of_university_assets.pdf.

- Menefee, H. 2018. Black activist geographies: Teaching whiteness as territoriality on campus. South: A Scholarly Journal 50 (2):167–86.

- Mitchell, C. 2020. With name changes, schools transform racial reckoning into real-life civics lessons. Education Week, December 18. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/with-name-changes-schools-transform-racial-reckoning-into-real-life-civics-lessons/2020/12.

- Moscufo, M. 2022. College campuses see growing reparations movement. ABC News, July 20. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://abcnews.go.com/US/college-campuses-growing-reparations-movement/story?id=87069082.

- Mulgan, R. 2014. Making open government work. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nicholls State University. n.d. Policy on naming facilities, spaces, units, and properties and other endowed gifts. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.nicholls.edu/policy-procedure-manual/5-general-university-policies/5-10-institutional-advancement-programs-and-policies/#5.10.6.

- Rose-Redwood, R. 2008. From number to name: Symbolic capital, places of memory and the politics of street renaming in New York City. Social & Cultural Geography 9 (4):431–52. doi: 10.1080/14649360802032702.

- Rose-Redwood, R. 2016. “Reclaim, rename, reoccupy”: Decolonizing place and the reclaiming of PKOLS. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 15 (1):187–206.

- Rose-Redwood, R., D. Alderman, and M. Azaryahu. 2010. Geographies of toponymic inscription: New directions in critical place-name studies. Progress in Human Geography 34 (4):453–70. doi: 10.1177/0309132509351042.

- Rose-Redwood, R., D. Alderman, and M. Azaryahu. 2018. The urban streetscape as political cosmos. In The political life of urban streetscapes: Naming, politics and place, ed. R. Rose-Redwood, D. Alderman, and M. Azaryahu, 1–24. London and New York: Routledge.

- Rose-Redwood, R., I. Baird, E. Palonen, and C. Rose-Redwood. 2022. Monumentality, memoryscapes, and the politics of place. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 21 (5):448–67.

- Rose-Redwood, R., J. Vuolteenaho, C. Young, and D. Light. 2019. Naming rights, place branding, and the tumultuous cultural landscapes of neoliberal urbanism. Urban Geography 40 (6):747–61. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1621125.

- Rusu, M. S. 2019. Mapping the political toponymy of educational namescapes: A quantitative analysis of Romanian school names. Political Geography 72:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.04.007.

- Rusu, M. S. 2021. Street naming practices: A systematic review of urban toponymic scholarship. Onoma 56:269–92. doi: 10.34158/ONOMA.56/2021/14.

- Sheehan, R. 2019. Rethinking memorial public spaces as regenerative through a dynamic landscape assessment plan approach. In Regenerative development: Urbanization, climate change and the common good, ed. B. S. Caniglia, B. Frank, J. Knott, K. Sagendorf, and E. Wilkerson, 187–203. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sumartojo, S. 2016. Commemorative atmospheres: Memorial sites, collective events and the experience of national identity. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (4):541–53. doi: 10.1111/tran.12144.

- Sysiö, T., O. Ülker, and N. Tokgöz. 2023. Assembling a critical toponymy of diplomacy: The case of Ankara, Turkey. Geopolitics 28 (1):416–38. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2021.1912022.

- Till, K. 2012. Wounded cities: Memory-work and a place-based ethics of care. Political Geography 31 (1):3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.10.008.

- University of California System. 2002. Policy on naming university properties, academic and non-academic programs, and facilities. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://policy.ucop.edu/doc/6000434/NamingProperties.

- University of Texas System. 2021. Naming policy. Accessed June 4, 2023. https://www.utsystem.edu/board-of-regents/rules/80307-naming-policy.

- Wideman, T. J., and J. R. Masuda. 2018. Assembling “Japantown”? A critical toponymy of urban dispossession in Vancouver, Canada. Urban Geography 39 (4):493–518. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2017.1360038.

- Wilder, C. S. 2013. Ebony and ivy: Race, slavery, and the troubled history of America’s universities. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Wright, J. K. 1929. The study of place names: Recent work and some possibilities. Geographical Review 19 (1):140–44. doi: 10.2307/208082.