Abstract

Objectives

Clinical trials demonstrated that golimumab is effective in anti-TNF naïve patients with ulcerative colitis. We aimed to assess the clinical effectiveness of golimumab in a real-world setting.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective cohort study, conducted at 16 Swedish hospitals. Data were collected using an electronic case report form. Patients with active ulcerative colitis, defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore ≥2 were eligible for inclusion. The primary outcomes were clinical effectiveness at 12 weeks and 52 weeks, i.e. response (defined as a decrease in Mayo score by ≥3 points or 30% from baseline) and remission (defined as a Mayo score of ≤2 with no individual subscores >1).

Results

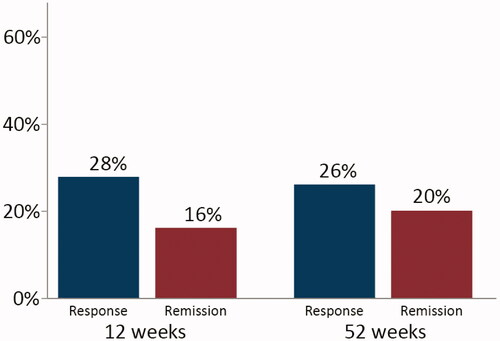

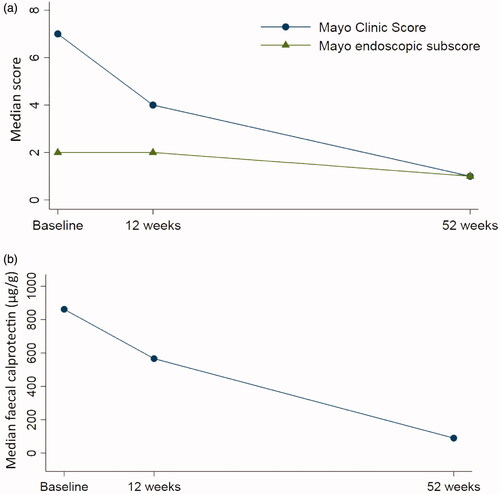

Fifty patients were included. At study entry, 70% were previously exposed to anti-TNF, 16% to vedolizumab, and 96% to immunomodulators. The 12 and 52-week drug continuation rates were 37/50 (74%) and 23/50 (46%), respectively. The 12-week response rate was 14/50 (28%), the remission rate, 8/50 (16%) and the corresponding figures at week 52 were 13/50 (26%) and 10/50 (20%). Among patients who continued golimumab, the median Mayo score decreased from 7 (6–9) at baseline to 1 (0–5) at 52 weeks (p < .01) and the faecal calprotectin decreased from 862 (335–1759) µg/g to 90 (34–169) µg/g (p < .01). Clinical response at week 12 was highly predictive of clinical remission at week 52 (adjusted OR: 73.1; 95% CI: 4.5‒1188.9).

Conclusions

The majority of golimumab treated patients represented a treatment refractory patient-group. Despite this, our results confirm that golimumab is an effective therapy in ulcerative colitis.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is the most prevalent type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the world [Citation1]. It is a disorder characterized by recurrent inflammation of the colon with increased stool frequency and rectal bleeding [Citation2].

The anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents infliximab and adalimumab have significantly improved management of ulcerative colitis patients, refractory to or intolerant of conventional treatment, i.e. corticosteroids, mesalamine and immunomodulators. The use of TNF-antagonists has been associated with reduced risk of colectomy and hospital admission, with increased quality of life [Citation3–5].

However, many patients do not respond to induction therapy, lose response during maintenance treatment, or become intolerant [Citation6]. Individual anti-TNF agents differ in their molecular structure, immunological properties, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity, and studies support the effectiveness of a second anti-TNF agent if the first one fails [Citation7,Citation8].

Golimumab is a fully human IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody directed against TNF, and was the third anti-TNF to be approved for use in ulcerative colitis by the European Medicine Agency (EMA). The approval relied on evidence from two randomized controlled phase 3 studies, the PURSUIT trials [Citation9,Citation10].

Study design and procedures in clinical trials do not accurately reflect routine clinical practice. For instance, all the patients in the PURSUIT trials were biologic-naïve [Citation9,Citation10]. It is therefore important to follow and report the effectiveness and safety of new drugs in a real-world setting. Observational studies of golimumab that included patients exposed to biologics demonstrated short-term response and remission rates with the drug that were in the range of those found in the pivotal trials [Citation11]. Most of these studies were performed at tertiary referral centres and there are few real-world data on long-term outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, only four reports of the 52-week clinical remission rate with golimumab have been published [Citation12–15] and only one of them gave detailed information on the long-term effect on endoscopic or biochemical activity [Citation14].

To assess the long-term clinical effectiveness of golimumab in a real-world setting, we performed a prospective national non-interventional study and gathered data prospectively using an electronic case report form (eCRF), integrated with the Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Register (SWIBREG). In addition, we wanted to identify predictors of remission, and describe the golimumab-treated patient population in Sweden.

Materials and methods

Patients

This prospective multicentre study was conducted at 16 Swedish hospitals (nine regional hospitals and seven university hospitals) connected to the SWIBREG. Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had a confirmed diagnosis of ulcerative colitis, moderate to severe disease activity (defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore of ≥2) [Citation16], and started on golimumab between June 2014 and June 2017. Exclusion criteria were contraindications for the use of golimumab (i.e. hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients, active tuberculosis or other severe infections, and moderate-to-severe heart failure) and/or planned cessation of treatment within 12 months of initiation (e.g. bridging or planned pregnancy). All patients provided their written consent to participate in the study.

Data collection

Demographics, clinical characteristics according to the Montreal classification [Citation17], medical and surgical treatment, clinical (Mayo Clinic score), biochemical (faecal calprotectin), endoscopic activity (Mayo endoscopic subscore) and health-related quality of life measures (Short Health Scale and EuroQual 5-Dimensions, 5-levels [EQ5D-5L]) were recorded at baseline, at 12 (±4) weeks, and at 52 (±4) weeks [Citation16,Citation18,Citation19].

The Mayo Clinic score consists of four components reflecting the disease activity of ulcerative colitis (stool frequency, rectal bleeding, physician’s global assessment, and the endoscopic subscore). The score ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating more active disease [Citation16].

The Short Health Scale is a four-item questionnaire for the assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. It reflects four aspects of health including symptom burden, disease-related worry, general well-being, and social function. Each dimension is scored from 0, representing no problem, to 5, representing the worst imaginable state [Citation19].

The EQ5D-5L is a self-reported questionnaire that evaluates five generic dimensions of current health status including mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The EQ5D-5L also contains a visual analogue scale (VAS) to assess the current state of health, which is converted into a score from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing a better health state [Citation18].

Data were gathered prospectively in a study database, using an eCRF, integrated with the SWIBREG, a national quality register [Citation20,Citation21].

Golimumab treatment and previous anti-TNF therapy

Golimumab therapy was administered subcutaneously according to the EU Summary of Product Characteristics recommendation, at an initial dose of 200 mg, followed by 100 mg at week 2. Thereafter, patients with a body weight of <80 kg and patients with a body weight of ≥80 kg received golimumab maintenance doses of 50 mg or 100 mg every four weeks, respectively [Citation9,Citation10]. However, this was an observational study and the treating physician was allowed to adjust the dose or change the interval between injections at any time. Reasons for discontinuation of golimumab and previous anti-TNF therapy were classified at the discretion of the investigator. The criteria for discontinuation of treatment were harmonised with the SWIBREG, and included primary non-response, secondary loss of response, intolerance (discontinuation due to side effects) or other reasons, including pregnancy.

The study was approved by the Linköping Regional Ethics Committee in 2014 (approval number: 2014/160-31).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were clinical effectiveness at 12 and 52 weeks, i.e. clinical response (defined as a decrease in Mayo Clinic score of ≥3 points or 30% from baseline) and remission (defined as a score of ≤2 with no individual subscore >1) [Citation16,Citation22]. Secondary outcomes included endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic subscore of ≤1) and biochemical response (defined as a faecal calprotectin value <250 µg/g) [Citation16,Citation22–24]. Finally, we assessed the effect of golimumab on health-related quality of life (Short Health Scale and EQ5D-5L) [Citation18,Citation19].

Predictors of response

We analyzed predictors of clinical remission at week 52 including age (continuous variable), sex, duration of disease (continuous variable), extent of disease (proctitis, left-sided colitis, or extensive colitis), concomitant drug therapy at baseline (use of corticosteroids or immunomodulators), previous anti-TNF use (yes or no) and clinical response at week 12.

Sample size

This was an observational study and no formal sample size calculation was performed. Instead, the sample size was based on the feasibility to collect data in a timely fashion and on the minimum number of observations needed to achieve adequate precision in the outcome estimates. The accuracy was expected to increase substantially up to a sample size of 120 patients and then slough off. The inclusion period was calculated as 2.5 years.

Statistics

Continuous data such as age, duration of disease, and data on an ordinal scale including Mayo Clinic score, faecal calprotectin levels, and health-related quality of life measurements are presented as median (interquartile range). Differences between baseline and follow-up were assessed with the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A survival plot depicting the cumulative probability of discontinuation of golimumab was constructed by Kaplan-Meier analysis. The EQ5D-5L index value calculator version 2.0, provided by the EuroQual group, was used to calculate EQ5D-5L index values [Citation25]. Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to evaluate predictors of clinical remission at week 52. Covariates were selected on the basis of their possible associations with the outcome. All tests were two‐tailed and a p-value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY: 2017).

Results

Patients

During a 3-year period (June 2014 to June 2017), 50 patients were included. Because of slow enrolment, it was decided to terminate the study, even though fewer patients than stated in the protocol had been included. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included are summarized in . Altogether, 35 of the 50 patients (70%) had previously been exposed to at least one anti-TNF agent and 8 (16%) had been exposed to vedolizumab. After initiation of golimumab treatment, six patients started corticosteroid therapy and three patients initiated treatment with an immunomodulator.

Table 1. Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with ulcerative colitis (n = 50).

Clinical effectiveness in the short-term

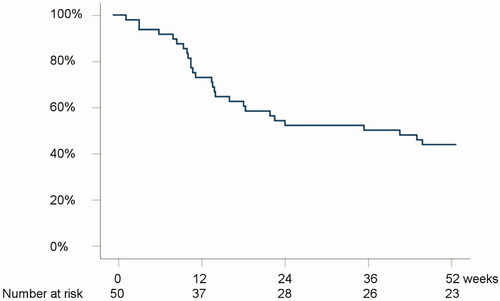

The 12-week drug continuation rate was 37/50 (74%) (). Reasons for termination of golimumab in the short-term were primary non-response (n = 11), or other reasons (n = 2).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis on the probability of remaining on treatment with golimumab during the follow-up period.

At 12 weeks from initiation of golimumab, 14/50 (28%) had a clinical response, 8/50 (16%) were in clinical remission, 15/50 (30%) were in endoscopic remission, and 13/50 (26%) had faecal calprotectin levels <250 µg/g (). However, data on endoscopic activity (n = 6) and faecal calprotectin (n = 9) were missing at 12 weeks among patients who continued the drug. Correspondingly, the median Mayo Clinic score decreased from 7 (6‒9) at baseline to 4 (2‒8) at 12 weeks (p < .01) and the median faecal calprotectin decreased, although not statistically significantly, from 862 (335‒1759) µg/g to 566 (45‒923) µg/g (p = .12) (). Information on golimumab continuation rate and clinical effectiveness at week 12, stratified by previous exposure to anti-TNF therapy, is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Clinical effectiveness in the long-term

The 52-week drug continuation rate was 23/50 (46%) (). Reasons for termination of golimumab within the first year from initiation were primary non-response (n = 15), secondary loss of response (n = 10) or other reasons (n = 2).

The 52-week response rate was 13/50 (26%), the remission rate was 10/50 (20%), the endoscopic remission rate was 12/50 (24%), and 16/50 (32%) had faecal calprotectin levels <250 µg/g (). However, two of the patients who continued golimumab until week 52 lacked data on both endoscopic and clinical activity, four of the patients lacked data on endoscopy, and five had no available faecal calprotectin value at week 52 ± 4 weeks. The 52-week colectomy rate was 7/50 (14%), and out of those, five patients had terminated the treatment with golimumab before the time of colectomy. None of the patients who underwent colectomy had responded to golimumab within the first 12 weeks of treatment. In patients who continued therapy, the median Mayo Clinic score decreased from 7 (6‒9) at baseline to 1 (0‒5) at 52 weeks (p < .01) and the median endoscopic Mayo Clinic score decreased from 2 (2–3) to 1 (0–2) (p < .01) (). Correspondingly, the median faecal calprotectin level decreased from 862 (335‒1759) µg/g to 90 (34‒169) µg/g (p < .01) (). Within a median time of 16 (13–19) weeks, nine patients increased the golimumab dose or shortened the interval between injections. Similar 52-week remission rates were observed between patients who underwent dose optimization and those who remained on original dose (33% vs. 17%; p = .36). Data on golimumab continuation rate and clinical effectiveness at week 52, stratified by previous exposure to anti-TNF therapy, are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Health-related quality of life

The well-validated, self-administered questionnaires Short Health Scale and EQ5D-5L were used to evaluate health-related quality of life at baseline and at week 52. Statistically significant improvements in all four health aspects in the Short Health Scale were observed in patients who continued on golimumab until week 52 (). Similarly, improvements were observed in usual activities, pain/discomfort, and in the VAS domains of the EQ5D-5L, whereas no statistically significant benefits were observed in mobility, self-care, and anxiety/depression (). The EQ5D index value increased from 0.73 (0.56‒0.80) at baseline to 0.86 (0.70‒1.00) at week 52 (p = .06).

Table 2. Health-related quality of life at baseline and at the end of follow-up.

Predictors of response

In order to identify predictors of clinical remission at week 52, a multivariable logistic regression model was constructed (). In the analysis, clinical response at week 12 was associated with clinical remission at week 52 (adjusted OR: 73.13; 95% CI: 4.50‒1188.92), while none of the other covariates in the model―including age, sex, duration of disease, extent of disease, concomitant drug therapy, and previous anti-TNF treatment―were significantly associated with the outcome ().

Table 3. Predictors of clinical remission at week 52.

Discussion

In this prospective multicentre study, the majority of golimumab-treated patients in Swedish clinical practice represented a treatment-refractory patient group in which 70% were previously exposed to anti-TNF, 16% to vedolizumab and 96% to immunomodulators. Despite this, our results support that golimumab is well tolerated, and has clinical effectiveness in active ulcerative colitis in the long-term [Citation9,Citation10]. In addition, we found that clinical response at week 12 was highly predictive of long-term clinical remission.

Data on the clinical effectiveness of golimumab in ulcerative colitis are sparse and most observational studies are limited by a short follow-up. Few studies have reported the long-term effect on clinical disease activity [Citation12–15] and only one of them gave extensive information on endoscopic or biochemical activity [Citation14]. In the present study, clinical remission was defined as a Mayo Clinic score of ≤2 with no individual subscore >1. By week 52, 20% of the patients were in clinical remission, 24% were in endoscopic remission (defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of ≤1) and 32% had a faecal calprotectin level <250 µg/g [Citation16,Citation22–24]. These figures are in line with the clinical remission rate of 18% observed in the prospective GO-COLITIS study from the United Kingdom [Citation13], with the rate of 28% (17/59) being reported by Orlandini et al. in patients treated with golimumab at two tertiary Italian centres [Citation12], and with the results of the PURSUIT-Maintenance trial in which 28% of the patients were in clinical remission by week 54

In previous reports on the short-term clinical effectiveness of golimumab, the results have varied considerably depending on the study population and on the definitions of response and remission [Citation12,Citation13,Citation26–32]. Bosca-Watts et al. reported that 70% of the patients managed at ten hospitals in the community of Valencia, Spain had a clinical response, defined as a decrease in partial Mayo Clinic score of ≥3 points by week 14, whereas the corresponding figure at a tertiary referral centre in Belgium was only 14% when a clinical response was defined as the absence of diarrhoea and blood [Citation26,Citation28].

By week 12, we observed that 28% of the patients had a clinical response and that 16% were in clinical remission. The corresponding figures in the PURSUIT-Induction trial, with biologically naïve patients only, were numerically higher with 51% of the patients having a clinical response and 18% being in remission [Citation9]. Data from both randomized trials and observational studies have indicated that the effect of a first anti-TNF treatment is superior to the effect of a second anti-TNF treatment when the first one has failed [Citation7,Citation33–35]. Thus, our lower response rate may be explained by the higher proportion of individuals exposed to anti-TNF in the cohort (70% vs. 0%) [Citation9].

Interestingly, after adjustment for potential confounders we observed a strong association between clinical response at week 12 and long-term clinical remission. This is in line with a recent study by Taxonera et al. who reported an 80% reduction in the risk of long-term drug discontinuation and an 84% decrease in the risk of colectomy in short-term responders [Citation31]. The finding is also consistent with the results of the BE-SMART study, where mucosal healing at week 14 was found to be associated with continuation of steroid-free golimumab at week 52 [Citation27]. Other previously reported predictors of treatment outcome, such as concomitant use of immunomodulators [Citation28,Citation36], low clinical disease activity [Citation28,Citation29], or previous use of anti-TNF [Citation26,Citation31], could not be confirmed as long-term predictive factors in our cohort.

To our knowledge, this was the first real-world study to evaluate the effect of golimumab on quality of life in an unselected cohort of ulcerative colitis patients comprising both biologically naïve and biologically experienced individuals [Citation13]. Golimumab therapy was found to be associated with significant improvements in both disease-specific and generic health-related quality of life, including improvements in bowel symptoms, pain/discomfort, worry, activities of daily living, usual activities, general well-being, and current health status as assessed with the EQ5D-VAS. The observed effect sizes were greater than the proposed cut-offs for minimum clinically important differences for the respective instruments [Citation18], and in line with the GO-COLITIS study, where similar estimates were reported among anti-TNF naïve patients [Citation13,Citation37,Citation38].

The observed colectomy rate (14%) at week 52 was numerically higher than in the BE-SMART study (3%) [Citation27]. However, the majority of patients had terminated golimumab before undergoing colectomy. In addition, the majority of patients included in the BE-SMART cohort (87%) were anti-TNF naïve [Citation27].

The main strengths of the present study were the prospective study design, systematically collected real-world data, the inclusion of patients from both regional hospitals and university centres (reducing the risk of selection bias), and the use of well-established disease activity indices, including both patient-based questionnaires [Citation18,Citation19] and objective endoscopic and biochemical measures [Citation16,Citation22–24]. In order to minimize selection bias, all eligible adult patients with active ulcerative colitis – both biologically naïve and experienced – who were starting on golimumab were invited to take part in the study. To ensure that all hospitals conducted the study per protocol, a remote monitoring regimen was implemented.

The main limitations of the study were the open-label design and the limited number of patients included. According to the protocol, 120 patients were intended to be included in the study. However, because of slow enrolment the study was terminated earlier, i.e. after inclusion of 50 patients only. One could only speculate on reasons for the slow enrolment, although the two other anti-TNF agents adalimumab and infliximab were approved for ulcerative colitis before golimumab and, therefore, it is possible that clinicians were more familiar with these drugs. Moreover, the introduction of anti-TNF biosimilars may have limited the use of anti-TNF reference products during the study period.

Due to the lower number of included patients, effectiveness was examined for all patients only, and not stratified by previous exposure and response to anti-TNF agents as outlined in the protocol. The inclusion of two patients with an ileorectal anastomosis may also have limited the study since we used the Mayo Clinic score to assess disease activity, i.e. an instrument that has not been validated for this group of patients. In addition, no data on golimumab concentrations were available. This limits the study further, since data from the PURSUIT studies have indicated that golimumab concentrations >2.5 μg/mL after induction and >1.4 μg/mL during maintenance seems to be associated with better outcomes [Citation39].

In conclusion, a majority of golimumab-treated patients in Swedish clinical practice represent a treatment-refractory patient group in which the greater part is exposed to both immunomodulators and anti-TNF agents. Nevertheless, golimumab had a clinical effect, i.e. induced and maintained clinical remission and improved health-related quality of life of the patients in the long-term. Clinical response at week 12 was highly predictive of long-term clinical remission.

Role of the funding sources

The study was initiated, planned, and undertaken by the investigators. The sponsors provided economic help for setting up the eCRF, entering data in the eCRF, investigators’ meetings, monitoring during and after the study was closed, and administrative work. The sponsor did neither have access to raw data nor conducted any of the analyses. The local hospitals paid for the golimumab.

Specific author contributions

CE and JH planned and conducted the study. CE, IV, LV, LN, HH, DB, SA, EH, PK, HS, JH and the GO-SWIBREG Study Group collected the data. CE and IV performed the data analyses. CE, IV, DB, and JH interpreted the data. CE and IV drafted the manuscript. CE, IV, LV, LN, AK, HH, DB, SA, EH, PK, HS, JH revised the manuscript. CE, IV, LV, LN, AK, HH, DB, SA, EH, PK, HS, JH and the GO-SWIBREG Study Group approved the final draft of the manuscript.

| Abbreviations | ||

| IBD | = | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| TNF-α | = | Tumour necrosis factor-α |

| EMA | = | European Medicines Agency |

| SWIBREG | = | Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Register |

| EQ5D-5L | = | EuroQual 5-Dimensions, 5-levels |

| VAS | = | Visual analogue scale |

| eCRF | = | Electronic case record form |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14 KB)Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of Malin Olsson, SWIBREG-registry coordinator, Linköping University Hospital and of Åsa Kälvesten, Kristin Klarström Engström and Ida Gustafsson, Clinical Trial Unit, Örebro University Hospital. We thank all the members of the GO SWIBREG Study Group: Lars Åke Bark, André Blomberg, Olof Grip, Fredrik Linder, Malin Lombert, Daniel Sjöberg and Mari Thörn.

Disclosure statement

CE: received grant support/lecture fee/advisory board from: Takeda, Janssen Cilag, Pfizer, AbbVie.

IV: has nothing to declare.

LV: has received lecture fee/advisory board from: MSD, Ferring and Tillotts Pharma.

LN: has nothing to declare.

AK: is an employee of MSD.

HH: has served as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member: AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Tillotts Pharma, Vifor Pharma, and received grant support from Ferring and Tillotts Pharma.

DB: has served as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member: Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda.

SA: has served as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member: AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, Tillotts Pharma, Vifor Pharma.

EH: has served as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member: AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda.

PK: has served as consultant: Ferring.

HS: has served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Gilead and Tillotts Pharma.

JH: has served as a speaker, consultant or advisory board member: AbbVie, Aqilion, Celgene, Celltrion, Dr Falk Pharma and the Falk Foundation, Ferring, Gilead, Index Pharma, Janssen, Lincs, MSD, Novartis, Olink Proteomics, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories Inc., Sandoz, Shire, Takeda, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tillotts Pharma, Vifor Pharma, and received grant support from Janssen, MSD and Takeda.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54.e42. quiz e30.

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–1770.

- Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, et al. Colectomy rate comparison after treatment of ulcerative colitis with placebo or infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1250–1260; quiz 520.

- Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Rutgeerts P, et al. The effects of infliximab therapy on health-related quality of life in ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):794–802.

- Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Lazar A, et al. Adalimumab therapy is associated with reduced risk of hospitalization in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):110–118.e3.

- Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, et al. Report of the ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures in inflammatory bowel diseases: definitions, frequency and pharmacological aspects. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(4):355–366.

- Gisbert JP, Marin AC, McNicholl AG, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of a second anti-TNF in patients with inflammatory bowel disease whose previous anti-TNF treatment has failed. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(7):613–623.

- Roblin X, Verot C, Paul S, et al. Is the pharmacokinetic profile of a first anti-TNF predictive of the clinical outcome and pharmacokinetics of a second anti-TNF? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(9):2078–2085.

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):85–95. quiz e14–5.

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab maintains clinical response in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):96–109.e1.

- Olivera P, Danese S, Pouillon L, et al. Effectiveness of golimumab in ulcerative colitis: a review of the real world evidence. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51(3):327–334.

- Orlandini B, Dragoni G, Variola A, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of golimumab in biologically experienced and naive patients with active ulcerative colitis: a real-life experience from two Italian IBD centers. J Dig Dis. 2018;19(8):468–474.

- Probert CS, Sebastian S, Gaya DR, et al. Golimumab induction and maintenance for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: results from GO-COLITIS (golimumab: a phase 4, UK, open label, single arm study on its utilization and impact in ulcerative colitis). BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2018;5(1):e000212.

- Bossa F, Biscaglia G, Valvano MR, et al. Real-life effectiveness and safety of golimumab and its predictors of response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(6):1767–1776.

- Berends SE, Strik AS, Jansen JM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of golimumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: the GO-KINETIC study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(6):700–706.

- Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(26):1625–1629.

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753.

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736.

- Hjortswang H, Jarnerot G, Curman B, et al. The short health scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(10):1196–1203.

- Eriksson C, Marsal J, Bergemalm D, et al. Long-term effectiveness of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease: a national study based on the Swedish National Quality Registry for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(6–7):722–729.

- Jakobsson GL, Sternegard E, Olen O, et al. Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the Swedish National Patient Register and the Swedish Quality Register for IBD (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(2):216–221.

- D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):763–786.

- D'Haens G, Ferrante M, Vermeire S, et al. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(12):2218–2224.

- Lobaton T, Rodriguez-Moranta F, Lopez A, et al. A new rapid quantitative test for fecal calprotectin predicts endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(5):1034–1042.

- van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715.

- Bosca-Watts MM, Cortes X, Iborra M, et al. Short-term effectiveness of golimumab for ulcerative colitis: observational multicenter study. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(47):10432–10439.

- Bossuyt P, Baert F, D’Heygere F, et al. Early mucosal healing predicts favorable outcomes in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis treated with golimumab: data from the real-life BE-SMART cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(1):156–162.

- Detrez I, Dreesen E, Van Stappen T, et al. Variability in golimumab exposure: a ‘real-life’ observational study in active ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(5):575–581.

- O'Connell J, Rowan C, Stack R, et al. Golimumab effectiveness and safety in clinical practice for moderately active ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(9):1019–1026.

- Samaan MA, Pavlidis P, Digby-Bell J, et al. Golimumab: early experience and medium-term outcomes from two UK tertiary IBD centres. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2018;9(3):221–231.

- Taxonera C, Rodriguez C, Bertoletti F, et al. Clinical outcomes of golimumab as first, second or third anti-TNF agent in patients with moderate-to-Severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(8):1394–1402.

- Tursi A, Allegretta L, Buccianti N, et al. Effectiveness and safety of golimumab in treating outpatient ulcerative colitis: a real-life prospective, multicentre, observational study in primary inflammatory bowel diseases centers. JGLD. 2017;26(3):239–244.

- Armuzzi A, Biancone L, Daperno M, et al. Adalimumab in active ulcerative colitis: a “real-life” observational study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45(9):738–743.

- Balint A, Farkas K, Palatka K, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis refractory to conventional therapy in routine clinical practice. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):26–30.

- Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):257–265. e1–3.

- Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):392–400.e3.

- Coteur G, Feagan B, Keininger DL, et al. Evaluation of the meaningfulness of health-related quality of life improvements as assessed by the SF-36 and the EQ-5D VAS in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(9):1032–1041.

- Stark RG, Reitmeir P, Leidl R, et al. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in inflammatory bowel disease in Germany. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(1):42–51.

- Adedokun OJ, Xu Z, Marano CW, et al. Pharmacokinetics and exposure-response relationship of golimumab in patients with moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis: results from phase 2/3 PURSUIT induction and maintenance studies. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):35–46.