?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms are intimately related to our wellbeing. The Short Health Scale for GI symptoms (SHS-GI) is a simple questionnaire to measure the impact of GI inconvenience and symptoms on quality of life. The aim was to validate the SHS-GI in a general population sample and to compare it with SHS-data across different patient groups.

Method

A subsample of 170 participants from a population-based colonoscopy study completed the Rome II questionnaire, GI diaries, psychological questionnaire (hospital anxiety and depression scale) and SHS-GI at follow-up investigation. Psychometric properties of SHS-GI as an overall score were determined by performing a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Spearman correlation between SHS total score and symptoms was calculated in the general population sample. SHS-GI data was compared with SHS data from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and fecal incontinence (FI).

Results

As expected, the general population rated their impact of GI inconvenience on quality of life as better than the patient populations in terms of all aspects of the SHS-GI. The CFA showed a good model fit meeting all fit criteria in the general population. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.80 in the general population sample and ranged from 0.72 in the FI sample to 0.88 and 0.89 in the IBD samples.

Conclusions

SHS-GI demonstrated appropriate psychometric properties in a sample of the normal population. We suggest that SHS-GI is a valid simple questionnaire suitable for measuring the impact of GI symptoms and inconvenience on quality of life in both general and patient populations.

Introduction

GI experiences and symptoms are extremely common in the everyday life of people, most often related to diet and lifestyle [Citation1], stress [Citation2,Citation3], side effects of medications [Citation4], being part of a GI disease [Citation5,Citation6] and sometimes also occurring without any obvious reason.

GI-experiences can affect health-related quality of life (HRQL) considerably and this has been proven in various GI disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [Citation7–15], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Citation16,Citation17–19], constipation [Citation20–22], dyspepsia [Citation23–25] or fecal incontinence (FI) [Citation26–32].

The gut and the brain are constantly communicating with each other through the so-called gut-brain axis and changes in gut function are therefore often associated with changed mood and vice versa [Citation33]. GI symptoms, such as accidental leakage of gas or stool or bloating can also be more or less devastating dependent on our psychosocial context [Citation30].

GI symptoms are frequent somatic complaints in the general population [Citation34–41]. Recently, it was shown in a nationwide Brazilian study that GI symptoms were present in the day-to-day life of two-thirds of women without social class distinction and in all regions of the country and most prevalent symptoms were gases, abdominal distention and constipation, affecting quality of life in a majority of these women [Citation1].

There are several questionnaires for measuring quality of life in GI patient populations and several specific HRQL questionnaires have been developed for example for IBD [Citation17,Citation42–45] or IBS [Citation46,Citation47]. However there exists, to our knowledge, no generally applicable questionnaire specifically designed and validated for measuring the impact of GI inconvenience and symptoms on quality of life in general. Such a questionnaire could for example be useful to compare different groups within the normal population in terms of GI-related quality of life, or it could be used to measure GI-related quality of life in non-GI disorders.

For this purpose, we have modified the existing Short Health Scale (SHS), a simple, self-administered visual analog scale questionnaire, which was developed to measure bowel disease impact on daily life and general well-being [Citation48]. The first three questions of SHS refer to the specific disease, while the fourth question covers the wider aspects of general well-being. In this study, we developed the SHS further and made it refer to GI inconvenience and symptoms instead of a specific disease to be able to use the questionnaire in the general population. For this purpose, the wording of the questions was slightly modified, while the response alternatives were left unchanged, and the questionnaire was named SHS-GI.

The original disease-specific SHS is a commonly used HRQL questionnaire and the validity, reliability and responsiveness of the SHS have been confirmed for several specific diseases [Citation47–49]. Hjortswang et al. developed the first version of SHS, referred to as SHS-IBD, and the first validation study was performed in 300 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) [Citation48]. UC patients in relapse scored significantly higher on each of the four SHS-IBD questions than patients in remission and there was a strong association between SHS-IBD score and their corresponding health dimension obtained with other HRQL questionnaires: The Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) [Citation50], Rating Form of IBD Patient Concerns (RFIPC) [Citation51] and Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) [Citation52]. In the same study, test–retest reliability was proved on repeated measurements with a 2-week interval and responsiveness was demonstrated since change in disease activity was significantly reflected by a change in SHS-IBD scores. Stjernman et al. demonstrated in 376 patients with Crohn’s disease that SHS-IBD was a valid, reliable and responsive HRQL instrument [Citation49] also for this patient group. Furthermore, the SHS-IBD has been validated in several languages including English [Citation53], Dutch [Citation54], Korean [Citation55], Norwegian [Citation56], Croatian [Citation57] and Chinese [Citation58]. Krarup et al. evaluated validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a modified version of SHS patients with IBS patients, this version is referred to as SHS-IBS [Citation47].

The primary aim with this study was to investigate the psychometric properties of SHS-GI in a sample of the general population as well as several specific GI populations in order to evaluate its applicability to pan-GI diseases. The secondary aim was to measure the impact of GI symptoms on the perceived health status in a sample of the general population and in comparison, with different patient groups with GI diseases.

Methods

Participants

General population sample

Data from the diary follow-up of the PopCol study was used in this study. In short, the PopCol study was conducted during 2002–2006 and a random sample of the inhabitants in Katarina and Maria parishes in Stockholm received a validated abdominal symptom questionnaire (n = 3556). All 2293 responders were phoned and asked to do a hospital visit and those without contraindications were asked to do a research colonoscopy with biopsies and 745 agreed [Citation59]. During the preparation hospital visit subjects were asked to fill out a 7-d abdominal symptom diary which was completed by 265 subjects. In 2010, those who had responded to the diary were contacted by mail and asked to complete the short health form (SHS-GI), HAD, Rome II questionnaire and a 14-d abdominal symptom diary. A total of 201 subjects that participated in the follow-up were included in this study. Mean age of the population sample was 55 years and 79% of subjects were women. All but five subjects had a colonoscopy during the PopCol study and no subject in this study had IBD. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Dnr. 394/01.

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Patients with IBD were included at their regular follow-up at the hospital. Disease activity was determined according to the physician’s global assessment as described earlier [Citation49,Citation48]. Mean age of the IBD patient cohort was 46.4 years and 53% were women. A total of 498 had CD where of 155 (31.1%) had active disease, and 307 had UC whereof 76 (25.3%) with active disease.

Patients with fecal incontinence

Patients with FI were prospectively evaluated at the Anorectal Physiology Unit, University Hospital of Linköping. Surgeons, gastroenterologists and primary-care physicians referred patients to this tertiary center for FI for evaluation and treatment. Mean age of the women with FI was 57 years. Patients had been suffering for an extended period, in median 4.5 years, of FI.

The studies concerning IBD and FI were approved by the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 02 − 220, Dnr 97-054 and Dnr 03-689).

Measures

Gastrointestinal short health scale (SHS-GI)

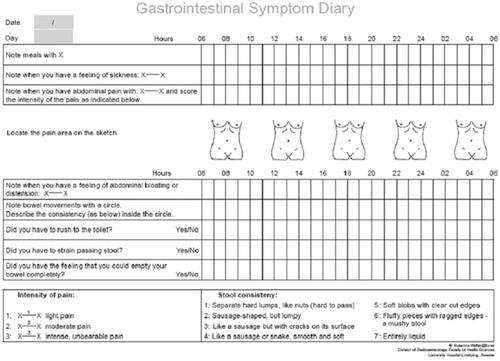

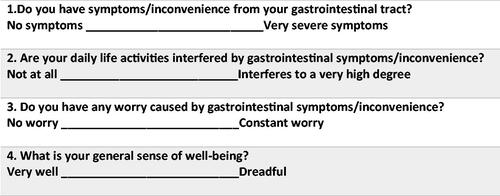

The SHS-GI is a 4-item self-administered questionnaire. Each item deals with one of the subjective health dimensions: symptoms, social function, disease-related worry and general well-being (). Responses are graded on a 100-mm visual analog scale and maximum sum score for all items is 400, with higher values indicating worse outcome. The results, presented as an individual score for each of the four items, form a profile. The SHS was originally designed to be presented as a profile with four dimensions. The summation of the four items into a total score was not tested in the original validation on UC or CD but has been validated in IBS [Citation47] and IBD [Citation53].

Figure 1. The general Short Health Scale (SHS-GI). Rating refers to symptoms/inconvenience during the last week.

To be able to use it in pan-disease populations, three of the four items of the original disease dependent SHS-IBD questionnaire were slightly changed to meet a more general need, see . The SHS-IBD question: ‘How severe symptoms do you suffer from your bowel disease?’ was replaced by the question: ‘Do you have symptoms/inconvenience from your gastrointestinal tract?’. In questions 2 and 3 the word ‘bowel disease’ was replaced by ‘symptoms/inconvenience from your gastrointestinal tract’. Question 4 remained unchanged.

Symptom diaries

Subjects recorded their bowel habits and symptoms prospectively on validated diary cards [Citation60] for 2 weeks (). Subjects recorded every single stool, stool consistency and corresponding defecatory symptoms (urgency, straining and feeling of incomplete evacuation). Stool consistency was defined by the Bristol Stool Form Scale [Citation61]. Subjects also recorded every meal, and episodes (start and ending time) of abdominal pain and bloating. All items were recorded along a 24 h time axis.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

HADS was used to estimate symptoms of depression and anxiety [Citation49] in the general population sample. The scale consists of seven items each for depression (HADS-D) and anxiety subscales (HADS-A), respectively, with scores on each subscale ranging from 0 to 21.

Rome II

Rome II modular questionnaire [Citation62] was used to define the subjects with IBS and functional dyspepsia (FD) in the general population sample as this was the current version of the criteria at the time data collection commenced.

Statistics

First, the psychometric properties were evaluated within the PopCol cohort. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of the 4-item single dimension structure of the SHS was performed. The fit of the models was evaluated using the residual Chi-square test (ideally p > .05), the ratio Chi-square/degrees of freedom (df) (ideally <5.0), the comparative fit index (CFI, ideally >0.95) and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI, ideally >0.95) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, ideally <0.05) [Citation63]. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated as a measure of internal consistency. Consistency of the weighting of each item to the total score across studies was evaluated through meta-analysis of the item loadings across studies and calculation of the I2 measure and Cochrane’s test of homogeneity (reported in ). The concurrent criterion validity was evaluated by correlating the total SHS-GI score with related construct measures () using Spearman’s correlations. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using Mann–Whitney rank-sum test and categorical variables by Chi-square test. Data on criteria variables were available for 182 subjects.

Second, CFAs were performed on the separate patient cohorts and the mean score of SHS-GI and model fit values were compared between the general population and separate patient cohorts. Cronbach’s alpha was again calculated within each cohort.

All analyses were performed in Stata version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Details of demographics and SHS scores in all samples are shown in . The general population had lower scores on all items and the total scale than the patient populations, with a median score of 32. Patients with UC reported lower scores than patients with CD (median 55 vs. 107) and patients with FI reported the highest scores with a median of 204. Notably, the FI sample reported a worse outcome on symptoms, social function and disease-related worry, but a better general well-being than patients with CD.

Table 1. Demographics, SHS scores and fit statistics in the different samples.

Interim correlations within the samples are presented in . The correlations between the GI-related items were high in all samples, ranging from 0.58 to 0.79. A high correlation was also seen between GI items and general well-being in both IBD samples. These correlations were lower in the general population (range 0.30–0.40), and in the FI sample, the association between GI items and general well-being were very low, ranging from 0.05 (symptoms – well-being) to 0.18 (function – well-being).

Table 2. Intercorrelations between SHS-items in the four samples.

The CFA showed a good model fit meeting all fit criteria in the general population, see . Same was true for the separate disease samples apart from UC which had a high CFI and TLI but not meeting the other model fit criteria. CFA statistics and Cronbach’s alpha values for all samples are shown in .

Cronbach’s in the general population was high at 0.88 and no individual item substantially increased or decreased

with

if any given item was omitted ranging from 0.82 to 0.89. Cronbach’s

was also consistently high across the patient populations, ranging from 0.73 to 0.89. Alpha measures the correlation between a given item and the other items, the higher alpha indicates better correlation to the other items.

Distribution of criteria variables in the general population sample is presented in and associations between SHS-GI scores and criteria variables in the general population sample are presented in . SHS-GI scores were significantly higher in women and in individuals with IBS or epigastric pain. A higher SHS-GI score was significantly associated with higher anxiety and depression scores, more pain episodes, days with pain, urgency, straining, without complete evacuation, with incomplete evacuation, without normal stool and days with loose stools while days with more than one bowel movement was not associated with total SHS-GI score.

Table 3. Criteria variables in the general population sample.

Table 4. Spearman correlation (Spearman’s Rho with p value) between SHS total score and items with criteria variables in the general population sample.

Discussion

The SHS-GI is a unique simple four-item questionnaire designed to measure how much GI inconvenience and symptoms affect quality of life. The overall aim of this study was to evaluate a number of dimensions of the validity of the SHS-GI for measuring the impact of GI inconvenience and symptoms on quality of life, disease-independently in more general settings of patients or people whenever the relationship between GI-symptom and quality of life is considered to be of clinical or scientific interest.

Mean SHS-GI scores increased with increasing amount and severity of GI symptoms. More specifically higher SHS-GI scores were associated with abdominal pain, defecatory symptoms (urgency, feeling of incomplete evacuation and need of straining) and lower number of stools with normal consistency. Moreover, subjects in this general population who fulfilled criteria for IBS and FD had higher SHS-GI scores, which was an expected finding based on multiple earlier studies demonstrating that functional GI disorders are affecting quality of life significantly [Citation7–15]. The population sample in this study was probably not fully representative for the general population since 79% of subjects were female. Since functional bowel disorders are moderately overrepresented in women our data may underestimate the difference between the general population and disease populations [Citation59]. Indeed, we found that 11.8% of subjects fulfilled Rome II criteria for IBS and 12.3% fulfilled criteria for FD which is slightly higher than earlier population-based questionnaire studies, also using the Rome II criteria: 10.5% in Great Britain [Citation64], 9.6% in the US [Citation65], 8% in Norway [Citation66] and 8.9% Australia [Citation67]. In another Swedish study, patients with mild IBS severity had a mean total SHS score higher than 120 [Citation47], differentiating strongly from the present population with a mean SHS of 53 and indicating that the potential overrepresentation of functional GI disorders is of minor significance, supporting the assumption that the present sample is representative for a general population.

HAD score is an instrument that performs well in assessing the symptom severity of anxiety and depression in somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients as well as in the general population [Citation68]. In this study, HAD scores for both anxiety and depression correlated significantly with SHS-GI score. This correlation was expected, since both GI symptoms and quality of life have been demonstrated to be associated with anxiety and depression [Citation28,Citation69,Citation70]. The mean values of the HAD scores in the present population were 4.9 (SD= 7.78) for anxiety and 2.6 (SD = 2.52) for depression, which was comparable with other general population samples. For example, Crawford et al. found a mean anxiety score of 6.1 (SD = 3.76) and depression score of 3.7 (SD = 3.07) in a non-clinical sample, broadly representative of the general adult UK population [Citation71].

The secondary aim of this study was to compare the SHS outcome in several populations. FI affects 2.2–15.3% of an adult general population [Citation72–74] and they curtail activities that other members of the society take for granted. Patients affected by FI reported a significant deterioration in their overall wellbeing. FI has been found to be psychologically and socially debilitating condition that can lead to embarrassment, social isolation and sometimes depression [Citation75]. These consequences contribute to the well-documented lower quality of life reported by individuals with the disorder [Citation76,Citation77]. Interestingly, the well-being item had a low alpha indicating a lower fit to the scale in this patient group. This may be explained by the long disease duration and that the patients had acclimated to their condition and their symptoms were less associated with worry and social isolation.

In this study, patients with active IBD and IBD in remission were mixed, and therefore, the SHS values are lower than for an IBD patient group with only active disease. The SHS data for these IBD patients separated by active disease and remission was published earlier [Citation78].

In this study, no evaluations of responsiveness or reliability were performed. These tests have been done in earlier SHS validation studies, in patient cohorts, with appropriate results [Citation47–49] and may be applicable also for SHS-GI.

A strength of SHS-GI is the open questions about GI symptoms. This allows people to refer to whatever GI symptom they experience and therefore makes SHS a very useful screening instrument to identify relevant or significant GI symptoms in a general way.

In conclusion, we provided evidence supporting the validity of the SHS-GI questionnaire in a sample of the general population and in comparison with several GI disorders. SHS-GI is designed to be used across multiple populations whenever clinicians or researchers are interested in measuring the impact of GI symptoms and GI inconvenience on quality of life.

SHS-GI is unique in its ability to compare different populations in terms of GI-dependent quality of life and since this instrument is short and simple and GI-symptom are commonly occurring in many different situations SHS-GI could potentially be used as an ‘add-on’ questionnaire in various clinical studies and situations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Del’arco A, Magalhaes P, Quilici FA. Sim brasil Study – Women's gastrointestinal health: gastrointestinal symptoms and impact on the Brazilian women quality of life. Arq Gastroenterol. 2017;54(2):115–122.

- Clevers E, Tornblom H, Simren M, et al. Relations between food intake, psychological distress, and gastrointestinal symptoms: a diary study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(7):965–973.

- Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, et al. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33(6):825–830.

- Walter SA, Kjellstrom L, Nyhlin H, et al. Assessment of normal bowel habits in the general adult population: the popcol study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(5):556–566.

- Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Tornblom H, et al. Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1262–1273 e3.

- Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome foundation global study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99–114.e3.

- Hahn BA, Yan SK, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60(1):77–81.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):654–660.

- Simren M, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, et al. Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome seen in referral centers versus primary care: the impact of gender and predominant bowel pattern. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(5):545–552.

- Motzer SA, Hertig V, Jarrett M, et al. Sense of coherence and quality of life in women with and without irritable bowel syndrome. Nurs Res. 2003;52:329–337.

- Bray BD, Nicol F, Penman ID, et al. Symptom interpretation and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(523):122–126.

- Simren M, Svedlund J, Posserud I, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients attending a gastroenterology outpatient clinic: functional disorders versus organic diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(2):187–195.

- Faresjo A, Anastasiou F, Lionis C, et al. Health-related quality of life of irritable bowel syndrome patients in different cultural settings. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(1):21.

- Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Jones MP, et al. What level of IBS symptoms drives impairment in health-related quality of life in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome? Are current IBS symptom thresholds clinically meaningful? Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(5):829–836.

- Naliboff BD, Kim SE, Bolus R, et al. Gastrointestinal and psychological mediators of health-related quality of life in IBS and IBD: a structural equation modeling analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(3):451–459.

- Varni JW, Shulman RJ, Self MM, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(6):e186–e192.

- Hjortswang H, Strom M, Almer S. Health-related quality of life in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(11):2203–2211.

- Hjortswang H, Tysk C, Bohr J, et al. Health-related quality of life is impaired in active collagenous colitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(2):102–109.

- Stjernman H, Tysk C, Almer S, et al. Unfavourable outcome for women in a study of health-related quality of life, social factors and work disability in Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:671–679.

- Glia A, Lindberg G. Quality of life in patients with different types of functional constipation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(11):1083–1089.

- Sun SX, Dibonaventura M, Purayidathil FW, et al. Impact of chronic constipation on health-related quality of life, work productivity, and healthcare resource use: an analysis of the national health and wellness survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(9):2688–2695.

- Wald A, Sigurdsson L. Quality of life in children and adults with constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25(1):19–27.

- Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. Impact of functional dyspepsia on quality of life. Digest Dis Sci. 1995;40(3):584–589.

- Talley NJ. Quality of life in functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;221:21–22.

- Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Quality of life in functional dyspepsia: responsiveness of the nepean dyspepsia index and development of a new 10-item short form. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(2):207–216.

- Rothbarth J, Bemelman WA, Meijerink WJ, et al. What is the impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(1):67–71.

- Bartlett L, Nowak M, Ho YH. Impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life. WJG. 2009;15(26):3276–3282.

- Walter S, Hjortswang H, Holmgren K, et al. Association between bowel symptoms, symptom severity, and quality of life in Swedish patients with fecal incontinence. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(1):6–12.

- Alsheik EH, Coyne T, Hawes SK, et al. Fecal incontinence: prevalence, severity, and quality of life data from an outpatient gastroenterology practice. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–7.

- Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Benninga MA. Fecal incontinence in adolescents is associated with child abuse, somatization, and poor health-related quality of life. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(5):698–703.

- Mundet L, Ribas Y, Arco S, et al. Quality of life differences in female and male patients with fecal incontinence. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;22(1):94–101.

- Brochard C, Chambaz M, Ropert A, et al. Quality of life in 1870 patients with constipation and/or fecal incontinence: constipation should not be underestimated. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2019;43(6):682–687.

- Mayer EA. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(8):453–466.

- Vandvik PO, Kristensen P, Aabakken L, et al. Abdominal complaints in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004;22(3):157–162.

- Sandler RS, Stewart WF, Liberman JN, et al. Abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea in the United States: prevalence and impact. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(6):1166–1171.

- Tielemans MM, Jaspers Focks J, van Rossum LG, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms are still prevalent and negatively impact health-related quality of life: a large cross-sectional population based study in The Netherlands. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69876.

- van Kerkhoven LA, Eikendal T, Laheij RJ, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms are still common in a general Western population. Neth J Med. 2008;66:18–22.

- Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L, et al. An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain. 1988;32(2):173–183.

- Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(21):2474–2480.

- Rief W, Hessel A, Braehler E. Somatization symptoms and hypochondriacal features in the general population. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):595–602.

- Lee AD, Spiegel BM, Hays RD, et al. Gastrointestinal symptom severity in irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and the general population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29(5):e13003.

- Hellers G. A new quality of life questionnaire for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 1992;59(1):56–57.

- Vergara M, Casellas F, Badia X, et al. Assessing the quality of life of household members of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: development and validation of a specific questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(6):1429–1437.

- Alcala MJ, Casellas F, Fontanet G, et al. Shortened questionnaire on quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:383–391.

- Casellas F, Alcala MJ, Prieto L, et al. Assessment of the influence of disease activity on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease using a short questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(3):457–461.

- Wiklund IK, Fullerton S, Hawkey CJ, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome-specific symptom questionnaire: development and validation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(9):947–954.

- Krarup AL, Peterson E, Ringstrom G, et al. The short health scale: a simple, valid, reliable, and responsive way of measuring subjective health in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(7):565–570.

- Hjortswang H, Jarnerot G, Curman B, et al. The short health scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(10):1196–1203.

- Stjernman H, Granno C, Jarnerot G, et al. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive instrument for subjective health assessment in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:47–52.

- Bodger K, Ormerod C, Shackcloth D, et al. Development and validation of a rapid, generic measure of disease control from the patient's perspective: the IBD-control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63(7):1092–1102.

- Hjortswang H, Strom M, Almeida RT, et al. Evaluation of the RFIPC, a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire, in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(12):1235–1240.

- Dupuy H. The psychological general Well-Being (PGWB) index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CF, Elinson J, editors. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. Darien (CT): Le Jacq Publishing Inc.; 1984. p. 170–183.

- McDermott E, Keegan D, Byrne K, et al. The short health scale: a valid and reliable measure of health related quality of life in English speaking inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(8):616–621.

- Coenen S, Weyts E, Geens P, et al. Short health scale: a valid and reliable measure of quality of life in dutch speaking patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(5):592–596.

- Park SK, Ko BM, Goong HJ, et al. Short health scale: a valid measure of health-related quality of life in Korean-speaking patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(19):3530–3537.

- Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Moum B. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: translation, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of the Norwegian version of the short health scale (SHS). Qual Life Res. 2012;21(9):1671–1676.

- Abdovic S, Pavic AM, Milosevic M, et al. Short health scale: a valid, reliable, and responsive measure of health-related quality of life in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(4):818–823.

- Zhu D, Zhou Y, Xu H. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the short health scale for inflammatory bowel diseases. Chin Nurs Manage. 2018;18:1630–1634.

- Kjellstrom L, Molinder H, Agreus L, et al. A randomly selected population sample undergoing colonoscopy: prevalence of the irritable bowel syndrome and the impact of selection factors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26(3):268–275.

- Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G. Division of the irritable bowel syndrome into subgroups on the basis of daily recorded symptoms in two outpatients samples. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(10):993–1000.

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920–924.

- Drossman DA. ROME II. The functional gastrointestinal disorders. Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment: a multinational concencus. 2nd ed. McLean (VA): Degnon Associates; 2000.

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Kerwer M, Klein AG. Evaluation of model fit in nonlinear multilevel structural equation modeling. Front Psychol. 2014;5:181.

- Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(504):495–502.

- Wigington WC, Johnson WD, Minocha A. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome among African Americans as compared with whites: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(7):647–653.

- Vandvik PO, Lydersen S, Farup PG. Prevalence, comorbidity and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(6):650–656.

- Boyce PM, Talley NJ, Burke C, et al. Epidemiology of the functional gastrointestinal disorders diagnosed according to Rome II criteria: an Australian population-based study. Intern Med J. 2006;36(1):28–36.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.

- Haug TT, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Are anxiety and depression related to gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(3):294–298.

- Brenes GA. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(6):437–443.

- Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, et al. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(4):429–434.

- Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, et al. Prevalence and burden of fecal incontinence: a population-based study in women. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(1):42–49.

- Karling P, Abrahamsson H, Dolk A, et al. Function and dysfunction of the Colon and anorectum in adults: working team report of the Swedish motility group (SMoG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(6):646–660.

- Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Fecal incontinence in US adults: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(2):512–7. 517 e1–2.

- Miner PB. Jr. Economic and personal impact of fecal and urinary incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(1):S8–S13.

- Bharucha AE, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, et al. Symptoms and quality of life in community women with fecal incontinence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(8):1004–1009.

- Meyer I, Richter HE. Impact of fecal incontinence and its treatment on quality of life in women. Womens Health. 2015;11(2):225–238.

- Hjortswang H, Jarnerot G, Curman B, et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire in Swedish patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(1):77–85.