Abstract

This paper arises from the authors’ preparation of the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture volume on Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire. As in previous volumes, we have looked hard at the manner in which the middle- and late-Saxon tradition of erecting ‘high crosses’ at significant locations, or to mark significant graves, was continued beyond the Norman Conquest in what we have called a ‘continuing tradition’ of monument type and design. Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire’s Anglo-Scandinavian stone sculpture is well known for its quantity, and this prolific local tradition of monument-making continued after the Norman Conquest. We focus here on five elaborately decorated Huntingdonshire ‘high crosses’ in the pre-Conquest tradition. They belong to two interrelated groups: two have a monastic context, three a secular one. Monuments at Fletton and Kings Ripton each marked significant points in the landscape. Whilst the monument at Hilton had an analogous function in perhaps marking a place of congregation, its date and use of architectural details also connects it with the pair of major monuments from Godmanchester and Tilbrook/Kimbolton, for which we suggest an additional political significance within the early cult of St Thomas of Canterbury.

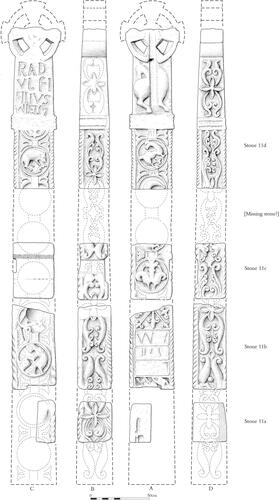

It has been many years since George Zarnecki discussed echoes of pre-Conquest art in English Romanesque sculpture.Footnote1 Many scholars have since considered the issue, and different aspects of form and design in English Romanesque art, in several different media, have been shown to have pre-Conquest origins. In particular, conferences on the subject were convened by the BAA in 2010 and 2012.Footnote2 Such issues have also been encountered during the compilation of the Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, where volumes by the present authors have included chapters and catalogues on the ‘Continuing Tradition’.Footnote3 Most recently, work on volume XIV in the series—covering historic Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire—has again identified the persistence and/or revival of Anglo-Scandinavian influences.Footnote4 This paper explores a group of five monuments in the Anglo-Scandinavian ‘high-cross’ tradition in Huntingdonshire, all made of stone from the Barnack quarries, that offer new perspectives on these issues ().

Fig. 1. Map showing locations of East Midlands sites mentioned in the text

Drawing and copyright authors

Zarnecki’s attention may have been first drawn to this topic through his detailed consideration of the sculpture of 1120–30 associated with the new cloister at Ely.Footnote5 He pointed to a host of minor details, as well as the design’s concern with a perceived horror vacui, to suggest that the sculptors of the early 12th century self-consciously harked back to Ely’s long monastic tradition of design in artworks, and thereby aimed to ensure that the early Norman reconstruction of the church, and its associated cloister, were firmly associated with pre-Conquest traditions of worship and saintliness. The elaboration of inhabited interlace seen on all three surviving Ely doorways; the way that the sculpture is designed around tendrils of more than one scantling; even the character of some of the human faces with which the doorways are embellished (with their ‘Anglo-Scandinavian’ moustaches) have all been seen, rightly, as indicators that these sculptors had inherited a tradition of decoration and embellishment that extended back at least as far as the 10th century, if not before; even if such earlier Ely traditions were expressed in ars sacra and manuscript art rather than in stone sculpture.

Indeed, an elaborately carved stone, re-set in the 13th century over the north doorway at St John’s Hospital in Ely (1 km west of Ely Cathedral), has long been included amongst Cambridgeshire’s pre-Viking sculpture. For the Corpus volume, however, we judge that the stylistic evidence that this sculpture was carved by the sculptors who worked on the cathedral cloister is overwhelming.Footnote6 Nevertheless, the fact that the stone at St John’s had been thought pre-Conquest in the modern period suggests that its 12th-century sculptor was probably also successful in giving the impression of antiquity to his/her contemporaries. We go further at Ely in proposing that two other finely sculpted loose stones, found separately in western Ely—Ely Cromwell House 1 and Ely Church Lane 1—and themselves also tentatively identified as pre-Conquest hitherto, are to be associated with that at St John’s Hospital.Footnote7 We suggest that all three stones originated in a single large, carved lintel, perhaps that belonging to the western entrance of the chapter-house in the new early Norman cloister.

PART I—TWO MONASTIC SHAFTS: FLETTON AND KINGS RIPTON

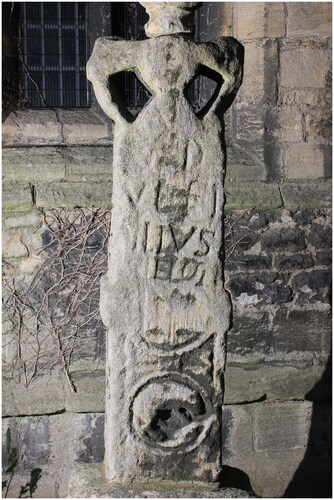

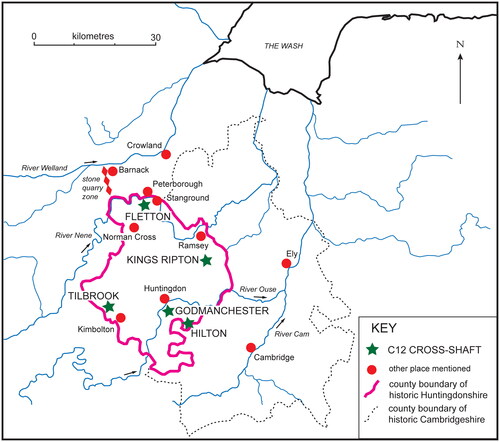

A) The ‘Radulfus Cross’ at Fletton

The Ely case may be only one example of wider 12th-century initiatives by the incoming Anglo-Norman monastic establishment, which aimed to consolidate its position in England by manufacturing a continuity with Anglo-Scandinavian predecessors. Something similar also occurred at nearby Peterborough Abbey, where the great Anglo-Scandinavian church was also the subject of a major campaign of reconstruction and expansion, beginning after a fire in 1116. As at Ely, a rich documentary archive underpins a robust understanding of the phases in which the work at Peterborough was undertaken.Footnote8 Using such documentation in combination with a reassessment of the settlement archaeology, we have recently suggested that a key figure in the subsequent development, reform and enlargement of the monastic landscape was Abbot Martin of Bec (1133–55).Footnote9 Other than architectural details in the monastic nave, little stone sculpture survives from Abbot Martin’s period, but we have proposed that the so-called ‘Radulfus Cross’ at Fletton, located just across the river Nene, represents a significant monument in Abbot Martin’s programme of reform and enlargement; and here we want to emphasize that, for this important position, he evidently commissioned a monument in the Anglo-Scandinavian tradition. Our recent rediscovery of three unconsidered sections of this cross makes it an enormous monument, originally standing about 4 metres tall (). The shaft has had a complicated and interesting history, which is explained in detail elsewhere.Footnote10 Those three sections are now stacked loosely inside St Margaret’s church at Fletton, whilst the fourth—the cross-head—still stands where it was placed in the 1830s, immediately west of St Margaret’s church tower ().

Date and Parallels

Our new reconstruction of the shaft reveals that it was decorated with distinctive foliage along its narrow sides and linked roundels on the broader faces (). Both these features can be thought of as Anglo-Scandinavian in origin. Furthermore, face C was dominated by a rectangular inscription panel, whose closest parallels are found on much earlier standing crosses, such as that at Bewcastle (Cumbria), but which now appears blank—the inscription having presumably been painted. The ‘Radulfus’ inscription, by which the cross has become named, is a later, probably early-14th-century addition to the monument.Footnote11

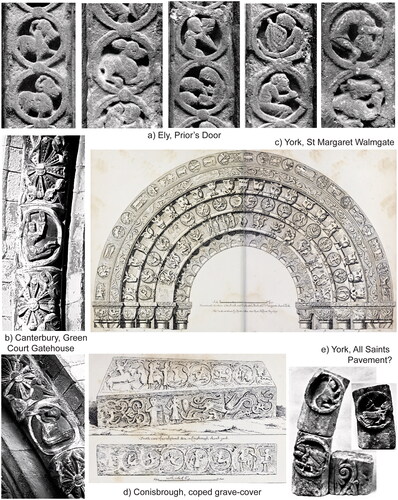

Nevertheless, the deeply carved roundels that dominate each of the shaft’s broad faces are a familiar Romanesque design feature, as is the style of foliage carving, with its distinctive trefoils and fleshy acanthus leaves. Similarly, the architectural mouldings decorating the terminals of the collar are also clearly of Romanesque type. Indeed, the shaft’s date can be refined more closely. Although the decoration of standing shafts with chains of roundels goes back to the 7th century, and indeed is dependent on Antique originals, in English stone sculpture such early roundels tend to be inextricably embedded within foliate designs. The trefoil ‘sprigs’ between each roundel at Fletton could be seen as the descendants of such earlier, more thorough-going, foliage trails. But here the roundels themselves are conceived independently, architectonically, as discrete design elements in themselves and, in this respect, they are more similar to 12th-century features in the Romanesque idiom. Such roundels frequently decorate smaller, more precious objects, like the three enamelled plaques from a casket in a private collection exhibited in 1984.Footnote12 In local stone sculpture in the English East Midlands, such roundels are widespread.Footnote13 Of particular relevance are the closely related inhabited examples decorating the outer jambs of the so-called Prior’s Door at Ely ().Footnote14 Here, the roundel frames are simplified, as they are at Fletton, although filled by more static-looking animals in profile, compared with the latter’s lively postures. Although foliage elsewhere on the Ely doorway is less fleshy and bears greater botanical detail than at Fletton, nevertheless the two schemes are clearly related. Zarnecki made a detailed case that the Ely Prior’s Door was carved between 1120 and 1130. When the Monks’ Door at Ely was carved, perhaps in the following decade, the winged quadrupeds had become more animated—and more like those at Fletton.Footnote15 The foliage quatrefoils in the jambs of the Monks’ Door at Ely are also reminiscent of, though not identical to, those on the narrow faces of the Fletton shaft. But an even closer parallel for Fletton is found decorating the archway of the Green Court gatehouse at Canterbury Cathedral priory, which has recently been dated to Prior Wibert’s building campaign in the 1150s ().Footnote16 Here, as at Fletton, the foliage bursts also alternate with inhabited roundels, each occupied by a single figure.

Fig. 4. Mid-12th-century sculpted roundels from architectural contexts: a) Ely Cathedral, Prior’s Door, jambs; b) Canterbury Cathedral, Green Court gatehouse, roundels in outer order; c) York, St Margaret Walmgate, south door—drawing of 1790, engraved 1791 by John Carter; d) Conisbrough, coped and sculpted grave-cover—drawing by John Carter; e) York, voussoirs thought to come from All Saints church, Pavement and now in the Yorkshire Museum a) Photos Zarnecki, Ely Cathedral, pls 84, 87, 89, 90, 92 b) Photos Fergusson, Canterbury Cathedral Priory, pls 96, 97 c) J. Carter, Specimens of Ancient Sculpture and Painting (London 1780–87), II, between 34 and 35 d) Carter, Specimens, II, between 52 and 53 e) Photo RCHME, Inventory of the Historical Monuments of the City of York Vol. IV. Outside the City Walls East of the Ouse (London 1975), pl. 28

Zarnecki wrote on several occasions about the interesting way the Ely sculpture self-consciously recalls Anglo-Scandinavian forms and stylistic details, and indeed about evidence for similar recollections in other English examples, such as the remarkable font at Coleshill (Warwickshire), which he dated to 1150–60.Footnote17 The sculpted roundel at Coleshill contains an image of the crucifixion, however, and not the fabulous figures which probably dominated the Fletton shaft. Roundels containing similar figures to those at Fletton are especially plentiful in Yorkshire, where they decorate orders within doorways in York itself at St Margaret’s Walmgate (), Alne (Yorkshire, North Riding), Brayton and Fishlake (both Yorkshire, West Riding) amongst others, as well as the fine coped and sculpted grave-cover at Conisbrough (; also Yorkshire, West Riding).Footnote18 These sculptures have all been considered to belong to periods of church elaboration between c. 1150 and c. 1180,Footnote19 whilst Rita Wood associates the Conisbrough grave-cover specifically with the third Warenne earl of Surrey, who died in 1148.Footnote20 Similar roundels containing animals are a commonplace in Romanesque art. Christopher Wilson suspects that the roundels on the loose voussoirs probably from All Saints Pavement, York, must be dated after c. 1140, though these encircled figures are not as lively as those at Fletton ().Footnote21 The inhabited roundels that decorate one of the shafts in the south jamb of the central door of Lincoln Cathedral are also animated, and they feature beasts with their heads straining backwards, like those at Fletton. Lincoln’s central doorway is dated to the later 1140s or early 1150s.Footnote22 Such examples all suggest that the Fletton sculptures were carved in the two central decades of the 12th century.

With the exception of the newly discovered shaft from Kings Ripton (below), similar inhabited roundels to those at Fletton are harder to parallel on cross-shafts. Nevertheless, in adjacent Lincolnshire, a ‘continuing tradition’ of erecting sculpted high crosses—of Anglo-Scandinavian type—during the mid-12th century includes some that were elaborately decorated with foliage sculpture.Footnote23 An example at Aunsby even has a roundel chain, not dissimilar to that at Fletton; but, compared with Fletton, the detail is lightly inscribed and is confined to geometrical patterns rather than animals or foliage. The fleshy acanthus trails on the 12th-century shaft from Digby, and on the head of the shaft from Revesby, are distantly related to the foliage at Fletton, but none of these Lincolnshire examples offers precise parallels, and none is in Barnack stone.

Parallels in both architectural decoration and on cross-shafts, then, suggest a mid-12th-century date for the Fletton monument, which we have argued elsewhere can also be associated with the abbacy of Martin of Bec (1133–55) for other reasons.Footnote24

Iconography

When the shaft was complete, the decoration of its neck immediately below the cross-head must have contributed to the iconographic meaning of the shaft as a whole. Although the animal forms might be taken for Anglo-Scandinavian ribbon beasts, as seems to be indicated on early drawings, both here and below the inscription panel, other interpretations are possible. Elsewhere on the shaft, animals survive in only five roundels: one a boar-like beast; one—possibly two—are fabulous, winged quadrupeds; a dragon-like creature with a long neck; and part of a second head or back leg. Given such unsatisfactory survival, recovering the shaft’s iconography might be thought impractical. We can say only that there was a selection of beasts, some fabulous and no doubt taken from bestiary accounts, for which we can suggest no overall programme. By comparing these images with illustrations in contemporary canon law manuscripts, however, Peter Fergusson has proposed that the figures in the roundels on the Green Court gate arch at Canterbury refer to the legal proceedings that were undertaken within the gate.Footnote25 Alternatively, for Wilson, the Yorkshire roundels at places such as All Saints Pavement and St Nicholas Hospital in York, Brayton, Fishlake and Alne, rather illustrate signs of the zodiac and/or labours of the months—a tradition which he suggests derives from mid-12th-century Burgundy, where such chains of roundels are also associated with major doorways.Footnote26 Supposing two roundels once existed on each of the missing faces of stone a, we can indeed suggest that there were originally twelve complete roundels in total on the combined faces at Fletton. It might have been decorated, then, with a zodiac or labours of the months; boars, for example, are frequently used in such cycles to denote the autumn months.

On the other hand, winged dragons of various sorts, again derived from the bestiary, inhabit the roundels of the south door at Kilpeck church (Herefordshire), where Malcolm Thurlby has proposed theological meanings for the images, including that they are mostly representatives of negative values.Footnote27 Although not apparently present at Kilpeck, the boar carries meanings in bestiaries that are again mostly negative and ‘related to gluttony and aggression’, and Rita Wood interprets the ‘boar-hunt’ as an allegory of the Church’s war on the devil.Footnote28 If the scenes on the Fletton cross deliberately invoked the bestiary, it would seem to stress potential dangers to the laity, and the church’s role in salvation from them. This would be an appropriate message for a monument erected at the gathering and marketing place south of the Nene bridge (below), although an iconography depicting the zodiac and/or the labours of the months would be just as suitable for this context.Footnote29

Location

We have argued elsewhere that the Fletton shaft was originally located on a distinctive knoll of open heathland, where three significant roads arrived at the southern approach to the river crossing from east, west and south and focused on the ancient Nene ford at this point.Footnote30 This was just up-river from the numinous river pool, in the north-west corner of Fletton parish, from which the early abbey’s name—Medeshamstede—derived. Here, a great cross with distinctive, backwards-looking, ring-cross silhouette would have surely been intended to suggest the antiquity of religious observance at this place and would signal to travellers that they had entered Peterborough’s ancient domain, just as we suppose the Kings Ripton cross did in respect of Ramsey Abbey (below). As part of Abbot Martin of Bec’s reorganization of the entire sacred landscape around Peterborough Abbey, we suggest that the Fletton cross was created to play this ‘introductory’ role to the abbey, and its anachronistic form as well as the design of its decoration served to evoke the antiquity of Christian presence in this location. Since this was also an ancient place of congregation, and site of the later Bridge Fair, the cross would also have overseen (and legitimated) trading on the surrounding heathland. Furthermore, travellers and traders—looking to the north-east, beyond the shaft in its elevated position on Fletton heath—would be afforded a clear view of the great abbey on the Nene’s northern shore and, at the right moment of the tide, a view of the bubbling whirlpool in the river before the abbey, overseen by it. The abbey thus stood guard for Christ, as it were, at the ancient, numinous and dangerously liminal place, where this world met the next.

Deploying major stone monuments to mark places where spiritually dangerous waters were crossed was a well-established tradition in Britain and Scandinavia. We have identified several pre-Conquest examples in midland England, such as that at Stapleford in Nottinghamshire.Footnote31 More distantly, the 4-metre-high Carew Cross on a tributary of the Cleddau (Dyfed) has similar characteristics. Although a century older, Carew Cross also supervises a significant river crossing (whose religious status is yet to be elucidated) and, like Fletton, it also has an inscription panel, thought to commemorate a local ruler.Footnote32 The self-consciously backward-looking form of the Fletton shaft would have been highly appropriate to the ancient traditions of such sites, evoking Christian forebears in its scale, form and decoration. Yet, with its Anglo-Scandinavian overtones, it was only a subsidiary detail in the reinvention of the entire Peterborough landscape under Abbot Martin, which culminated in his obtaining symbolic confirmation of Peterborough’s pre-Conquest possessions from Pope Eugenius III in 1147.Footnote33

B) The Kings Ripton Shaft

The shaft fragments from Kings Ripton, discovered only in 1983, represent a monument of comparable type to Fletton’s Radulfus Cross ().Footnote34 Although much less survives of this shaft, originally it was also a prominent landscape marker, here associated with Ramsey Abbey. Here, too, the designer appropriated pre-Conquest traditions of cross-shaft making, employing large forward-facing standing figures within a complex and learned iconographic scheme. Although the knowing onlooker would have understood its sophisticated iconographic message, most contemporaries would probably have read it merely as a cross made in a traditional form, legitimately located in a meaningful landscape location, even though it was newly erected in the 12th century.

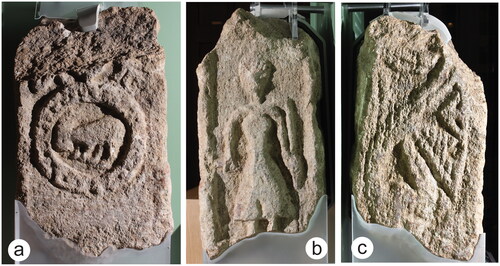

Fig. 5. The Kings Ripton cross fragment: a) broad face A; b) right-hand narrow face B; c) left-hand narrow face D

Photos and copyright authors

As it is now displayed, the battered and weathered remains of the Kings Ripton shaft are set within a tailor-made armature in the gallery of local antiquities at the Norris Museum in St Ives (Acc. no. 83.6). This arrangement unfortunately precludes inspection of face C. It has been harshly treated, with serious mechanical damage at both ends where it has been crudely broken out of the monolithic cross-shaft above and below. The surviving central section was originally decorated with high-quality sculpture in bold relief on all four faces, with a neatly cabled roll-moulding elaborating the angles, now largely missing. It is carved from Barnack stone.Footnote35

In the lower part of face A, a transverse fillet separates off a rectangular panel, with a smoothed surface, of which only a small area survives. Above this panel, a quadruped stands within a circular frame, formed from a bold raised fillet punctuated with circular dished depressions, originally of substantial depth and possibly intended for inserts of coloured paste or stones. The well-modelled quadruped within the roundel stands head down, with horns—or antlers—depicted above and behind the head. The surviving roundel was evidently linked to details on the shaft above (perhaps further roundels, as at Fletton) by means of a foliage sprig, of which only the lower stalk now survives. From their limited remains, the leaves themselves had deeply dished tips and appear to represent characteristically Romanesque acanthus.

On face B, traces of a transverse fillet have survived, suggesting this face was originally subdivided into rectangular panels. Within one panel so defined stands a full-frontal figure, addressing the onlooker. The feet are missing, though they presumably stood on the panel-frame, and the legs protrude from below a long skirt, with a central pleat, gathered tightly at the waist. The torso takes a triangular form, with swelling breasts. Above the breasts, the arms are joined to the torso in a manner indicating some form of breast-plate, perhaps with faint traces of narrow straps over the shoulders. Above an extended neck, the well-proportioned head might have been deliberately defaced, although the stone has suffered badly from incidental damage. Nevertheless, the female figure clearly wore a substantial ‘hair-piece’, with long ‘curls’ radiating symmetrically from the face. Both arms hang beside the body. In the left hand she grasps a stick-like implement that lies alongside the upper body. It is held towards its lower end, whilst its upper end turns inwards at a right-angle. Her right hand is now damaged, but it originally held a rectangular object transversely, traces of which extend towards the frame. For iconographic reasons explored below, this figure may have originally been one of four on face B, suggesting that the shaft originally stood at least 2 metres high. We can also presume a cross-head above that, and a socket-stone beneath.

Although face C is no longer accessible, an outline drawing of it was published by David Haigh, and photographs are available at the Cambridgeshire Sites and Monuments Record.Footnote36 On this face the original sculpted surface has only survived in the upper third of the stone; it was clearly carved with a standing figure in low relief, surviving only below the knees. The figure was dressed in a long shin-length gown, but without surviving articulation. Below the hem, the ankles protrude, with feet apparently turned leftwards.

Evidently face D carried an accomplished foliage trail, carved in low relief. It is organized, conventionally, around a thick stalk—with incised medial line—winding symmetrically from side to side, throwing off fronds. The most prominent surviving frond, however, is not leaf-shaped, but rather a sub-rectangular fillet containing an area of cross-hatching. This unusual detail may represent a ‘flower’ or a ‘berry-bunch’, presumably completed in paintwork. Above and below, fronds have articulated stalks and dished and curled leaf-tips of more conventional acanthus-type.

Date and Iconography

Prior to its publication, Steven Plunkett considered Kings Ripton to belong to a disparate group of early shafts from eastern England that included those from Fletton, Stanground (Huntingdonshire), Sproxton (Leicestershire), Great Ashfield (Essex) and Digby (Lincolnshire), all of which he considered to represent ‘post-Viking innovation’ in pre-Conquest sculpture.Footnote37 Plunkett thus demonstrates—however unintentionally—not only that these Romanesque sculpted high crosses are related to each other, but that they belong to the same pre-Conquest high-cross tradition, even though all of those nominated, Stanground perhaps apart, have now been re-dated to the post-Conquest period. Pre-Conquest heritage is particularly clear from close consideration of the Kings Ripton shaft’s iconography (below), but stylistically there can be little doubt that its sculpture dates from the 12th century. In particular, its close associations with the Fletton shaft, which above we link with the Peterborough abbacy of Martin of Bec (1133–55), suggests a similar date in the mid-12th century for Kings Ripton.

Kings Ripton shares several stylistic and design similarities with Fletton. Not only are both decorated with inhabited roundels, but those roundels are linked together into a loose ‘chain’ by similar-looking, centrally placed, symmetrical, foliate sprigs. Even so, the Kings Ripton shaft could have accommodated only four or five roundels comparable with that surviving on face A, and it seems unlikely that as many as twelve can be reconstructed, as is possible at Fletton. It may be, then, that a ‘seasons’ cycle is precluded at Kings Ripton, although John McNeill has pointed out to us that such cycles might be implied by fewer than twelve independent scenes: the one standing in for the entire cycle. Comparable inhabited roundels at the Prior’s Door at Ely have been explained as a battle between virtues (in the west jamb) and vices (in the east jamb), a theme which might have also been appropriate for the Kings Ripton shaft, given the decoration on face B (see below).Footnote38 Haigh thought the encircled animal at Kings Ripton was a ‘sheep’, and that it might have represented the Agnus Dei.Footnote39 But this quadruped undoubtedly has substantial horns. It is rather stocky and low to the ground to represent a deer, and it is not clear what iconographic meaning that might carry. But perhaps this animal is intended to represent the ram of Ramsey? Such an identification would be very appropriate to the suggestion made below about the shaft’s original location and purpose.

The reserved panel towards the bottom of face A, interrupting the sequence of roundels, very likely contained a painted inscription. It compares with the inscribed Latin inscription in the panel on the 12th-century shaft at Great Ashfield, for example, and—less closely—with the unframed inscription on the ‘Guthlac’ shaft, marking the boundary of the monastic domain at Crowland Abbey.Footnote40 Once again, though, in its inscription panel Kings Ripton finds its closest parallel at Fletton and, like Fletton, it also carries an elaborate foliage-trail, even if the trail at Kings Ripton is more closely modelled on earlier ‘vine-scroll’ motifs.

Unlike Fletton, however, the Kings Ripton shaft also features tiers of hieratic standing figures on faces B and C, and this is also a feature borrowed from the Anglo-Scandinavian high-cross tradition. The female figure on face B can be identified by her attributes. The strangely shaped ‘stick’, held at the bottom, with a horizontal element at the top, is best interpreted as a torch. The flames of the torch, rising above the horizontal element, would have been added in paint on the smoothed panel reserved for this purpose. A flaming torch, of precisely this form and held in the same manner, is seen in several contemporary images of the virtue Temperancia (‘restraint’, ‘moderation’). A close parallel is found, for example, in the glass of the north oculus window in the eastern transept at Canterbury Cathedral, made during the 1180s ().Footnote41 Images of Temperancia usually equip her with two attributes, one in either hand. While the flaming torch is sometimes replaced with a flowering bough, or a sword, she always carries a jug or bowl of water. This is presumably what is outlined in her right hand at Kings Ripton. Julianus Pomerius (430–90) explains why Temperancia is shown with these two attributes together in his De vita contemplativa, where he says ‘ignem libidinosae voluptatis exstinguit’.Footnote42 Temperancia, along with her fellow virtues, is also often shown crowned; so what appear to be curls radiating from her head at Kings Ripton would be better interpreted as a crown.

Fig. 6. Figure of Temperancia in glass from the oculus in the north wall of the north transept at Canterbury Cathedral

Caviness, Windows, pl. 12 No. 30. Photo and copyright Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi

As one of the four cardinal virtues, alongside Prudentia, Justicia and Fortitudo, Temperancia is frequently depicted in medieval art.Footnote43 With her flaming torch and jug of water, for example, she appears in the Autun Sacramentary,Footnote44 dated to 844–55, and, with the same attributes, in the dedicatory image of the Cambrai Gospels, usually dated to the ensuing decades of the 9th century.Footnote45 Katzenellenbogen documented how Temperancia’s attributes develop with time, and in the Gospels of Henry the Lion (1129/31–95), she carries a blossom bough rather than a torch, along with her jug.Footnote46 Nevertheless, in the 12th century she is more frequently seen with torch and jug, and she carries these two attributes into the early 14th century, when she appears holding them in the De Lisle Psalter.Footnote47 Furthermore, in the Canterbury glazing Temperancia occurs alongside Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel, explained by Madeline Caviness as traditional ‘types’ of the evangelists or apostles. At Canterbury and elsewhere, these four prophets support depictions of Moses, figured as ‘Synagogue’, in contrast with Christ, figured as ‘Church’.Footnote48 This iconography also occurs in several 11th- and 12th-century manuscripts.Footnote49 This pattern of occurrence might suggest that the lower third of the figure on face C at Kings Ripton represents one of these prophets.

Location

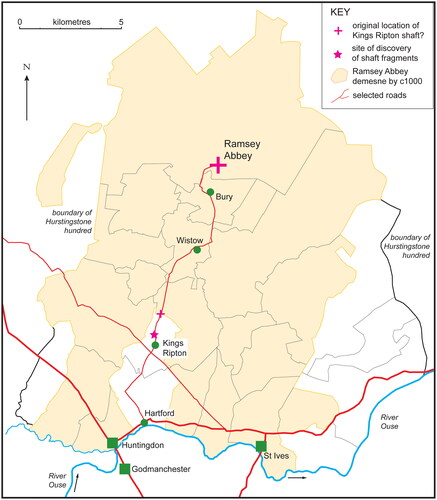

The 1983 excavation showed that the Kings Ripton shaft had been reused during the second half of the 16th century, along with several other stones with an original ecclesiastical provenance, in the abutments of a small bridge over the stream on the road northwards out of Kings Ripton village ().Footnote50 This bridge probably went out of use in 1773, when the stream shifted course some 50 metres further south, and a new bridge was constructed. It is possible that the spolia used to construct the 16th-century abutments was brought from some distance, but a potential source for the cross-shaft itself lay much nearer at hand and is thus more likely. A 15th-century court roll mentions a ‘Ramsey Cross’ within the parish of Kings Ripton itself, and although, unfortunately, its precise location is not reported, the cross’s name clearly associates it with the Ramsey Abbey estate.Footnote51 The high clay-land plateau around Kings Ripton, between Ramsey and Huntingdon, was evidently greatly wooded, and until the 12th century it was divided into only two holdings: the king’s demesne and that of the abbot of Ramsey.Footnote52 A charter of Henry I had granted the king’s demesne at Kings Ripton to the abbey, however, in return for a substantial annual fee, that continued to be paid until the Dissolution. Throughout the 13th century, however, Kings Ripton men complained that they were not accorded appropriate tenancy terms, compared with their counterparts on the abbey’s demesne, and therefore the boundary between the two estates remained contested, and would need to be marked, especially within woodland (as the disputes related to pannage amongst other rights).Footnote53 Consequently, we suggest that ‘Ramsey Cross’ in Kings Ripton parish marked the boundary between royal and abbey demesnes; between the parishes of Kings Ripton and Broughton. This boundary lay about 1 km north of the site of the bridge excavated in 1983, at the point where the road to Ramsey crossed another stream ().Footnote54

Fig. 7. Proposed original setting of Kings Ripton cross, based on Hart, ‘Foundation of Ramsey Abbey’, fig. 3 with additions

Drawing and copyright authors

The suggested ‘Church vs Synagogue’ iconography on the Kings Ripton cross, along with the four virtues and the vine scroll indicating Christ’s Passion,Footnote55 would very appropriately mark entry to the great abbey’s demesne. ‘Church vs Synagogue’ iconography at Kings Ripton would also symbolize passage from the secular world of ‘Synagogue’ into the sacred reservation of ‘Church’. Iconography on the Kings Ripton shaft, then, can be adduced to support the suggestion that it represents a fragment of the ‘Ramsey Cross’, erected on the Kings Ripton parish boundary to mark entry into Ramsey Abbey demesne, in the same way that the Fletton shaft marked entry to the demesne of Peterborough Abbey. Unfortunately, because of loss of detail, we cannot now tell if the Fletton cross’s iconography was similarly sophisticated. If commissioning the Fletton shaft formed a key part of a campaign of definition and consolidation of the Peterborough estates under Abbot Martin (1133–55), as suggested above, we might likewise suggest that the Kings Ripton shaft formed part of the similar programme of recouping estates undertaken at Ramsey under Abbot Walter (1133–60). Walter was praised for developing the abbey’s estates after the 1140s, following the abbey’s disruption during the Anarchy, and he is also credited with having constructed the causeway at Bury, offering pilgrims a suitable approach to the abbey church.Footnote56 The road to the Bury causeway entered the abbey’s demesne at the Kings Ripton parish boundary with Broughton.

Fletton and Kings Ripton—Continuity or Revival?

These two cross-shafts at Fletton and Kings Ripton are stylish and sophisticated sculptures in a fully mature Romanesque manner of the mid-12th century, and evidence of their likely original locations within their local landscape gives them an additional layer of significance, beyond style-critical analysis. Earlier examples exist of crosses used in this way as monastic boundary markers, situated at significant points on major routeways, at the threshold of monastic estates. Guthlac’s stone at Crowland has already been mentioned, with its well-documented location.Footnote57 The so-called Lampass Cross at Stanground may be another such example.Footnote58 It was recovered in the 1860s from a location well to the south of the village, reused as a bridge on the Farcet road. Gerald Baldwin Brown, who wrote a surprisingly full account of it, published posthumously in 1937, asserted that the Lampass Cross ‘seems to have stood in old times looking directly east along a road that runs to Whittlesea’.Footnote59 That is, where the cross-fen causeway to Whittlesey and beyond joined the north–south road along the fen-edge through the villages from Yaxley to Stanground. Here, travellers from the east, or on a ferry across the Nene that in the Middle Ages took people to and from Thorney and Crowland, entered a zone south of Peterborough where Thorney estates were dominant in the parishes lining the Fen edge.Footnote60 At the southern end of those estates stood Norman Cross—no longer extant as an early sculpture but clearly documented as a pre-Conquest feature and hundredal meeting-place.Footnote61 It, too, marked a significant road junction, but, additionally, historians have noted Thorney’s insistence that Norman Cross should be the meeting place for the hundred, as a marker of its own control.Footnote62 Thorney’s proprietorial concerns give further support to the case that Norman Cross was a physical monument, as well as a notable crossroads, and both this monument and the Lampass Cross at Stanground may have had similar contemporary political resonance, marking the boundaries of Thorney’s jurisdiction, as we propose at Kings Ripton and Fletton. The abbeys of Crowland, Thorney, Peterborough and Ramsey, then, can all be seen appropriating the iconographic language of the Anglo-Saxon past in these impressive post-Conquest monuments to assert their claims to ancient rights of ownership and rule in the 12th-century landscape. These indications of an East Midlands monastic tradition, deploying major stone crosses of self-consciously pre-Conquest type as markers of monastic territory, seem to suggest a conscious revival of form and function exemplified by the newly discovered monuments at Fletton and Kings Ripton.

Many years ago, in discussing the idea of a 12th-century renaissance in England, Sir Richard Southern famously proposed that such a movement was initiated by monks and furthered by seculars.Footnote63 Here we have seen examples of monastic boundary crosses exemplifying these same initiatives and trends. They take the evocative form of high crosses of an earlier age, carrying complex and sometimes learned sculptural decoration, which all allude to recognizably earlier iconographic traditions, while at the same time being of the best contemporary execution. Fletton and Kings Ripton may also illustrate choices made by notably capable and dynamic heads of houses, at Peterborough and Ramsey, for the form and decoration of monuments to stand in the public realm that they judged would reify claims to institutional antiquity that were so vital to those institutions.

PART II—THREE ‘SECULAR’ CROSS-SHAFTS AND THE EARLY CULT OF ST THOMAS OF CANTERBURY

In this second part of our study we deal with three further Huntingdonshire cross-shafts at Godmanchester, Tilbrook and Hilton. They too were intended to stand prominently in the public domain and to convey complex ecclesiastical and political ideas that were important to their patrons. Furthermore, in line with Southern’s basic thesis, they are a generation or so later in date than our two monastic examples, and they are bound together by a common thread of secular patronage, and by an overtly political purpose. If we are correct in our understanding of them, two of them, and perhaps all three, were informed by one of the great political issues of Henry II’s reign: the response of the king’s intimates to the martyrdom of Thomas Becket in December 1170.

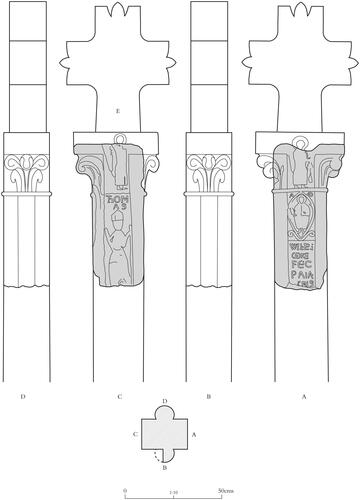

C) The Godmanchester Cross

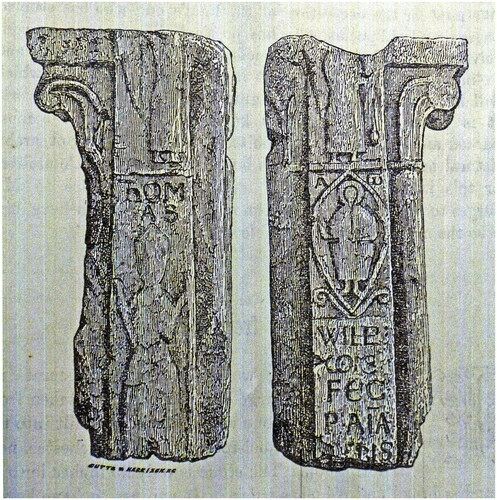

In 1871, the Church Builder reported the discovery of ‘an interesting stone which was lately built into the wall of the School-room at Godmanchester’, and provided a woodcut ().Footnote64 The woodcut is signed by ‘Cutts’ and engraved by ‘Harrison’. This is presumably, Edward Lewes Cutts (1824–1901) the well-known ecclesiologist, and author of the widely distributed Manual, amongst many other works.Footnote65 Cutts may even have written or supervised the 1871 article. The engraver was perhaps Samuel Harrison (b. 1823); ‘the famous line-engraver’ and father of a dynasty of engravers.Footnote66 Over a century later, John Hadley related the Church Builder report to a second in St Mary’s church parish magazine, which noted that the school re-opened following alterations in November 1871, and he proposed that this stone had come to light during the course of these works.Footnote67 He also reported that the stone had subsequently been lost.

Fig. 8. The Godmanchester cross: the only known image of the monument From The Church Builder, 37 (1871)

Although the sole image, the likely involvement of Cutts offers a degree of confidence in the depiction of the Godmanchester cross, and in particular that the transliterations had been given scholarly consideration. Nevertheless, the woodcut shows serious mechanical damage on all surfaces, and also that the shaft had been recut along one narrow side (face B), apparently for reuse as a window cill. The original lower end of the shaft section had been broken away, removing the lowest parts of the sculpture on face C, part of the inscription on face A, and damaging the upper platform (face E). The ‘beheading’ of two sculpted figures on the shaft below demonstrates that the stone has been cut down by several inches. The woodcut also shows a depression cut into face E, apparently for securing the cross-head, which was, therefore, carved in a second block. Evidently this stone represents the upper part of a major standing cross-shaft, decorated with relief sculpture on its broad faces (A and C) and with a centrally placed single colonette on the narrow faces (B and D). These colonettes supported a pair of capitals, of early ‘foliate volute’ type, with leaf-stalks represented prominently on the neck, of which only one survives in comprehensible form. The abacus above was cut square and apparently unmoulded.

The sculpted broad face A is divided into three approximately equally sized parts. The lower panel, below an incised line, contains a neatly cut inscription, tidily executed in Roman capitals, but with some letters, notably the critical ‘E’ (if that is what it is) in uncial. The anonymous author of the article in the Church Builder transliterated it as

WILL:CO(-)E:FEC:P:AIA: … S

This inscription is more problematic than it appears.Footnote68 In line 1, W I and L are clear but several possibilities might be considered for the fourth letter. It has the basic form of an L matching the preceding letter, but the horizontal is somewhat longer than its immediate companion and there is also a loop suggesting a possible P, though it takes a different form to the certain P at the beginning of line 4. Both the loop and the shortened horizontal might best be explained as an error, perhaps involving an original suspension mark and some surface damage. The author of the Church Builder article was surely correct, though, that ‘WILL’ is the best reading, perhaps followed by a mark of punctuation or abbreviation.

The first two letters of line 2 read C O; but reading of the third letter is complicated by its close proximity to letter 4. With its full rounded form, this might perhaps be a C—very similar to the C of fecit in line 3—rather than E (as the Church Builder read it). Nevertheless, something is inscribed within the curve of letter 4, even if it is not certainly a mid-height bar (it appears not to extend left into the mid-centre of the C, in way that the uncial E in line 3 clearly does). Noting the proximity of letters 3 and 4, however, we propose that letters 3 and 4 represent a ligatured M and E. Traces of another colon abbreviation mark then follow: the whole thereby straightforwardly making the abbreviated title ‘comes’. This reading resembles that proposed for it by the author of the Church Builder account, and Hadley’s glossing of that interpretation, but offers an explanation—as they do not—for letter 3. Just possibly these subsequent marks might suggest an abbreviation indicating a familial relationship and lead to alternative readings of the following, problematic, element in line 3 as a second personal name, but we can only be sure of the reading ‘CO [-] [-]’. Everyone agrees that line 3 reads ‘F E C: ‘ and line 4 is just as clear; it reads ‘P: A I A’. Two of three initial letters have been removed from line 5 by damage that is carefully portrayed in the engraving, which is followed by a probable T and clear ‘R I S’.

Despite uncertainties in detail, this is clearly a conventional donor inscription, organized around the third line word fecit (‘made’). In most circumstances this word stands for fieri fecit (‘caused to be made’), since it is the donor and not the craftsperson who is named as the subject.Footnote69 This donor is identified in lines 1 and 2: WIL is surely Willelmus (William), regardless of the meaning of the marks that follow. Syntactically, line 2 ought to represent an abbreviated name or title; and our reading proposes a title—comes, ‘earl’. Lines 4 and 5 record those persons in whose memory the shaft has been raised and take the form of an appeal for prayers for their souls. This appeal is appropriately located immediately below the image of Christ in Judgement. Uncertainty over the surface detail here means that we cannot be sure whether a single soul is involved (anima) or whether an abbreviation mark indicates souls in the plural (animabus): line 5 could have read [PA]TRIS, [MA]TRIS, or even perhaps [FRA]TRIS. Nevertheless, the final surviving part of the inscription appears straightforward: the cross was made pro anima [pa]tris/[ma]tris ‘for the soul of [William’s] father/mother’.

So, our detailed review leads us to propose the following transliteration:

WILL: COM/E: FEC: P: AĪA: [-] [-] TRIS

Above the line dividing the dedicatory inscription panel from that above, the surface is carved in low relief, and is completely filled with a mandorla or vesica, supported on two symmetrically placed foliate stems with curled tips to their leaves. In the spandrels created in the upper parts of the mandorla are placed two carved uncials, ‘A’ and ‘ω’. Within the mandorla sits a nimbed figure, ankles together, feet splayed. No detail is depicted in the bulky garments, although both arms extend inwards at the elbows, each apparently carrying an attribute. That in the left hand might be a sceptre, represented by the single vertical stroke across the upper part of the torso. The alpha and omega inscription, the seated posture of the nimbed figure, and the arms apparently holding attributes (perhaps an orb and sceptre) suggest that this is probably an image of Christ in majesty.

This sculpted panel is divided from that above by an astragal that extends across the face of the shaft from the capital on face B. Above it, and standing directly on the astragal, is a figure comparable to that in the same position on face C (below). The figure turns to face to its left on two small feet protruding from beneath a long ankle-length gown. Both arms are held across the body, the left apparently holding a staff. Behind the figure’s back a swelling line might indicate wings. The figure’s head was lost when the upper part of the stone was trimmed.

The tall, narrow panel on face C is decorated with two standing figures, apparently carved in relief. The lower figure clearly represents a bishop, standing frontally, facing the viewer. He wears a mitre and his right arm is raised in blessing whilst the left supports a tall shaft. The shaft’s terminal is not clearly depicted in the woodcut, but it is likely to have been either a crozier, or a cross-staff. No detail of his dress is discernible, but above him an inscription in uncial capitals reads (in two lines, with the first two letters a ligature):

T/HOM

AS

Although Hadley thought the woodcut illustrated a decorated architrave, there can be little doubt that it represented the upper part of a major cross-shaft, with its cross-head originally carved on a second stone (). Many local 12th-century shafts employed details derived from contemporary architectural decoration, generally having colonettes, capitals (and bases) along the angles of the monument. Typically, such shafts have four undecorated angle-rolls, like those at Great Staughton 2, Great Stukeley 2 and Longstanton 1.Footnote71 But Godmanchester takes a most unusual form, with only two large examples of such shafts centrally placed in the narrow sides, although the cross-shaft of this form at Torre Abbey (Devon) is also said to be of late-12th-century date.Footnote72 This unusual profile indicates that the Godmanchester monument was relatively thin, and that might suggest that it was made of Barnack ragstone, which—though immensely strong, and available in the great lengths suitable for standing shafts—came from the quarry in relatively thin slabs, compared to shafts quarried from Ancaster or Lincoln stone.

Date and Iconography

Dating the Godmanchester shaft is relatively straightforward. The bishop on face C stands in a posture associated with English bishops in the middle and later 12th century and is seen on many episcopal seals of this date, such as the first seal of Bishop Richard of Winchester, of 1174–88.Footnote73 This would be consistent with the inscription to St Thomas of Canterbury, following his death in December 1170 and canonization shortly thereafter. It also suits the architectural parallels for the capitals, which, with their foliate volutes, represent a type derived from the new choir at Canterbury Cathedral, built after 1174. The possible seated majestas figure in the mandorla on face A is similar in posture to the figures on the exceptional Tournai marble grave-cover now in the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, usually associated with the burial of Bishop Alexander and so dated to the 1150s.Footnote74 But Jack Wilcox has now proposed that this monument represents a post-hoc commemoration of Bishop Remigius dating from nearer 1200.Footnote75 Taken alongside the inscription, such details suggest a date for the cross in the late 1170s, or slightly later. They are probably too early, however, to link the erection of the cross with the Charter of Rights granted to the men of Godmanchester by King John in 1212.Footnote76

The two decapitated figures that originally sat below the cross-head are less easily dated, and their iconographic meaning remains unclear. The 1871 woodcut seems to give them wings, and therefore they might represent angels. But it is less easy to offer parallels for their postures or for their location immediately below the cross-head. Perhaps the angels’ wings have been misinterpreted and the figures represent, rather, Stephaton and Longinus at the foot of the cross-head above. Such iconography is found on the ‘Tall’ or ‘West’ cross at Monasterboice (County Louth), of the early 10th century, for example.Footnote77 Although Irish in origin, a tradition of angels attending crucifixions on high cross-heads was imported into England in the 10th century, for example at Durham Cathedral.Footnote78

More significant for the iconographic context of the Godmanchester shaft, however, is the large standing figure of a bishop on face C. Placing bishops in prominent locations on such shafts is also reminiscent of Irish practice. Sometimes in similar postures of blessing, they occur on numbers of major Irish crosses.Footnote79 Commonly paired with crucifixions—often placed above the bishop in the cross-head, as may also have been the case at Godmanchester—many of these Irish episcopal shafts have been dated to the 12th century.Footnote80 In contemporary England, however, and apart from the Huntingdonshire monuments under consideration here, there are fewer parallels for similar episcopal iconography. Cross-shafts at Barnborough, Thrybergh, and perhaps at Rawmarsh (all Yorkshire, West Riding) have hieratic standing figures of this type, and all have been dated to the 12th century; but not all are positively identified as bishops.Footnote81 In Ireland, this iconography, foregrounding the episcopate, has been explained as propagandistic stress on the doctrine that access to Christ’s redemption at the crucifixion (typically shown in the cross-head) is only available to the laity through the intercession of the established Church, personified by its episcopal leaders. The episcopacy was newly (re-)established in Ireland in the 12th century, of course. As well as being a reference to a specific case, then, the erection of a monument with comparable ‘episcopal’ iconography in Godmanchester, in the final quarter of the 12th century, and after Becket’s murder, must have also represented a similarly bold statement about the Church’s power to mediate between Christ and the laity.

In addition to this broader political message, however, we propose that the reference to Thomas Becket on the Godmanchester shaft carried a much more specific resonance, dependent on the identification of the patron named in its dedicatory inscription. Hadley suggested that the shaft was erected by William, king of Scots and earl of Huntingdon between 1165 and 1174.Footnote82 It is true that, following his participation in the Young King’s rebellion, and his capture at Alnwick in 1174, William of Scotland also had an interest in declaring a newfound loyalty to the English crown, and he undoubtedly acquired a devotion to Becket, to whom he dedicated his newly founded abbey at Arbroath in 1178.Footnote83 But William was deprived of the earldom of Huntingdon in 1174, and his family did not regain their position in the county until 1190.Footnote84 This period of forfeiture coincides rather precisely with the likely date-bracket of the cross on style-critical grounds.

More likely, we suggest, is that the prominent—and early—reference to Thomas Becket points to William de Mandeville, third earl of Essex, as a stronger candidate for identification as patron of the Godmanchester shaft. De Mandeville had played a significant role in directing the attack on the sainted archbishop, having been put in charge of Henry II’s ‘official’ task-force sent to negotiate with the prelate in December 1170, which arrived too late to prevent Becket’s murder by Henry’s ‘unofficial’ envoys.Footnote85 Unlike the four murderers themselves, de Mandeville was not subject to specific papal sanctions and exile for the deed.Footnote86 Nevertheless, he followed in their footsteps and performed very public penance for his subsidiary role in the murder by preparing to take the cross to the Holy Land in 1177; a journey he postponed in order to accompany Philip of Burgundy on his own penitential visit to the new shrine at Canterbury (and on which he also conducted Louis VII of France on his return from the Middle East in 1179).Footnote87 With his considerable military and diplomatic skills, allied to a personal bond of friendship, de Mandeville was constantly at Henry II’s side and engaged in royal business; including, presumably, on the king’s expedition to Ireland in 1171–72.Footnote88 This latter venture—though widely perceived as a means of removing the king from popular opprobrium in England in the immediate wake of Becket’s murder, when he was dogged by the saint’s disapproval—had the legitimate and papally approved purpose of confirming and reinforcing the reorganization of diocesan structure put in place by the synod of Kells twenty years earlier.Footnote89 Consequently, members of the royal entourage might well have observed examples of those newly carved high crosses bearing episcopal figures that represented the public face of that reorganization.Footnote90

Returning from Ireland, and with the papal doom on the murderers delivered, as John Guy has explained, Henry II was ‘brazen’ in promoting St Thomas’s cult, and public gestures were a critical aspect of his penance.Footnote91 We suggest that the Godmanchester cross represents just such a ‘brazen’ gesture by Henry’s right-hand man, William de Mandeville. Furthermore, we will suggest that the prominence given to Becket on the major cross erected on de Mandeville’s Kimbolton/Tilbrook manor strongly reinforces the connections between him and the early cult of the saint and adds further credibility to the proposal that the ‘William’ mentioned on the Godmanchester cross refers to de Mandeville.

Unfortunately, we have no documentary evidence that de Mandeville had similar standing at Godmanchester to that he held in contemporary Kimbolton: nevertheless, a case for his close connection with the town in the 1170s can be made. Although the manor of Godmanchester had passed to the earls of Huntingdon by 1190, it had previously long been a part of the crown estate.Footnote92 Furthermore, in July 1174, the town inevitably became the base for the royal army’s attack on Huntingdon Castle, across the Ouse, which was William of Scotland’s principal English seat and was held for the Young King during his revolt. Henry II himself came directly from his most public penance at Becket’s tomb scarcely a week earlier and was present at the castle’s surrender on 21 July, its occupants placing themselves at the king’s mercy ‘save life and limb’.Footnote93 Becket dominated political thinking on this stage-managed royal occasion, and the transfer of his allegiance away from the Young King, graphically exemplified by Henry’s complete victory at Huntingdon, the first of many, was promptly ascribed by contemporaries to God’s forgiveness for Henry’s role in Becket’s murder, through his recent penance at Canterbury.Footnote94

William de Mandeville’s role in Henry II’s attack on Huntingdon castle in July 1174 is not recorded, but it is likely he was prominent. Not only was he one of Henry’s closest advisors, but he also commanded Henry’s English armies the previous year.Footnote95 Similarly, although we cannot know what relationship de Mandeville might have had with the town of Godmanchester, his likely presence in July 1174, alongside the king, indicates at least a temporary residence here. If we are correct, the inscription on the cross might itself represent evidence for de Mandeville’s role in the successful attack on the castle, in addition to any more substantial interest in the town: it is conceivable, for example, that he leased the manor from Henry II during this period, from 1174 until his death in 1189.

Finally, the likely commemoration of a parent on the Godmanchester cross might also help reinforce a connection between the ‘William’ who donated the cross and de Mandeville. William’s father had died as long ago as 1144; however, his mother—Rohese de Vere—was still alive in 1170, but is presumed to have died in the ensuing two or three years, that is, just before the inscription records ‘William’ erecting the cross commemorating his parent(s).Footnote96

Original Location

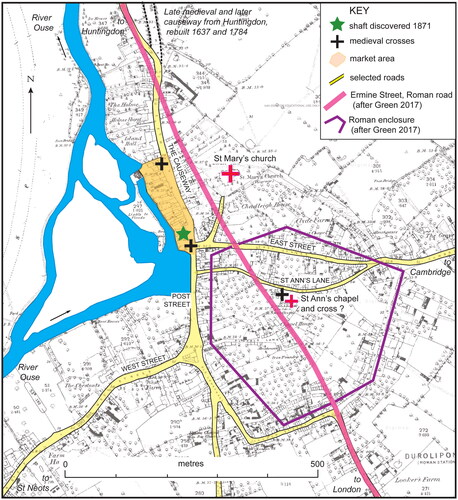

Evidence survives for several public crosses in medieval Godmanchester. The town clearly developed on quite a different plan to its Roman predecessor, Durovigutum, and to some extent negotiated the residual footprint of the Roman walled enclosure and a reserved area around the church ().Footnote97 There is no satisfactory published account of that process, however. Most clearly, two crosses stood north and south in the main street originally known as The Causeway on the road from Huntingdon, where they are recorded incidentally on an early map, perhaps dated 1515, drawn up to illustrate a dispute between inhabitants of Godmanchester and Huntingdon and the abbot of Ramsey.Footnote98 The crosses seem to have marked out a market or trading area on the river frontage, whose infilled outline can be detected in modern mapping. Significantly, the residual open space contains public buildings. The southern of the pair stood close the street junction with East Street, which continued eastwards as the road to Cambridge. This is the point, too, where the north–south thoroughfare originally became Post Street going southwards. One or other of this pair of crosses was a sufficiently prominent public feature in 13th-century Godmanchester for a family to take their name from it: the surname ad crucem was first reported in the Hundred Rolls.Footnote99 Presumably it is the southern of the pair that was thought by the Victoria County History editors to have been the ‘St Ann’s Cross’ mentioned in 1526 and 1545, though they propose a more southerly location—opposite the west end of St Ann’s Lane—as justification for the name.Footnote100 More probably this was another cross, sited near to St Ann’s chapel, whose traditional site is identified several hundred metres to the east, at NGR TL 246 704 near the eastern end of St Ann’s Lane.Footnote101

Fig. 10. The Godmanchester cross: suggested original location as market cross

Drawing and copyright authors

Of these possible candidates, the southern cross of the market-place pair, located opposite the end of East Street, would have stood directly outside the Elizabethan Old Schoolhouse, built after 1561, and the discovery of the Godmanchester shaft in the schoolhouse fabric in 1871 must make it the most likely candidate for the monument reconstructed in .Footnote102 The separate cross-head itself had clearly disappeared before the monument was built into the wall from which it was recovered; but, given that the head end was trimmed square, perhaps this shaft was itself ‘beheaded’, as was the fate of many public crosses, before being reused as building material.Footnote103

Consequently, it seems quite possible that, as at Kimbolton (see below), erection of this cross in the later 1170s or 1180s marked the initiation of a formal market on the riverside at Godmanchester. Furthermore, its name suggests that The Causeway was an artificial public space raised above the prevailing level, negotiating lower-lying riverside conditions which had previously been avoided by routeways. As The Causeway clearly diverged from the well-established Roman road alignment through the town, it was likely its replacement. As late as 1844, the southern end of The Causeway had to be raised two feet to remain above flood-water.Footnote104 The abandonment of the Roman line of this major highway, until resumed at the southern exit from the town, left the ancient church isolated, whereas it had formerly stood closely by the road, and it set a new framework for the layout of the medieval and modern settlement, with its oddly complex plan-form. The ambition of this radical market development—perhaps dated by the reconstructed cross itself to the late 12th century—matched a similar market development at Kimbolton, that we propose was also marked by an equally imposing new cross.

D) The Tilbrook (Kimbolton) Cross

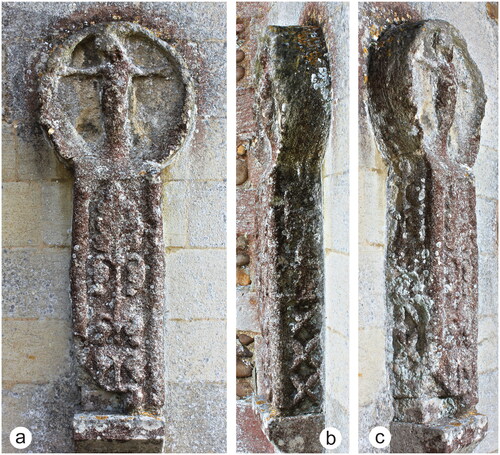

The discovery and identification of the two stones now at Tilbrook church that represent a fourth major cross-shaft is quite involved and is explained elsewhere ().Footnote105 Briefly, they were discovered just before the First World War, reused in the abutments of an early modern bridge north of the church and, taken together, they represent a large sculpted monolithic cross-shaft of Barnack stone, that stood at least 3 metres tall above its base (). The sculpted surface is deeply and evenly weathered all over, indicating a period standing in open space, prior to reuse within the bridge abutment, though face A has also been abraded subsequently by running water, presumably during that phase.

Fig. 11. The Tilbrook/Kimbolton cross: a) the remains of the cross today; b) detail of bishop, showing the careful chisel damage to mouth

Photos and copyright authors

Fig. 12. The Tilbrook/Kimbolton cross: reconstruction of original monument from two surviving stones

Drawing: Dave Watt, copyright authors

The shaft is essentially square in section and is profusely decorated in high relief, between angles marked with boldly undercut roll-mouldings. Within the angle rolls, face A has a complex foliate motif at the base, above which rises a boldly projecting column of segmental section. Because of water abrasion, this foliate motif is not easily understood, but it represents, in effect, a large sub-square boss, subdivided into four parts, each containing a single three- or four-leaved acanthus-frond. These fronds are swept to the right, giving the whole boss a sense of dynamism, whilst the leaves themselves were evidently once carefully moulded and deeply dished. The projecting ‘column’ above the foliate motif supports a moulded astragal, above which sits a well-carved, well-preserved spray of symmetrically disposed foliage. The spray is in two parts: a pair of bold spiral forms at the base that develop into an upright palmette of acanthus-style decoration of three separate fronds above. Although these leaves, and the foliage below, are all recognizably derived from Romanesque acanthus types, they also look forward towards stiff-leaf forms. Above the three fronds, the projecting column continues upwards to a second astragal, supporting a second spray of acanthus-style foliage below the lower arm of the cross-head. This second spray is similarly disposed to the one below, though considerably larger in scale.

Only the lower arm of the integral cross-head above survives on face A, the remainder having been trimmed away. The original cross-form itself was evidently composed around four circles, as is found in the widely distributed series of Barnack grave-covers that carry a ‘bracelet-headed’ cross type.Footnote106 The cross-arms themselves are defined by a bold roll developing out of the angle rolls running along the length of the shaft and, with added geometrical sophistication, the interstices between the cross-arms have boldly chamfered arrises, lending the cross-arms themselves a sub-octagonal cross-section. On this face the chamfered surface thus created within the cross-arm is also decorated with fronds of upright acanthus-style foliage, although the surfaces of the opposing chamfer were treated differently. The cross-head’s centre on face A is marked by a raised, diamond figure. This highly decorated cross-head, like the shaft below, relied on surface articulation for impact, no doubt originally enhanced by colour.

Between the two angle-rolls face B was entirely plain but, like face A, broad face C has a substantial foliate boss (here clearly a patera), close to the base of the shaft’s surviving decorated surface, where the angle-roll mouldings turn inwards to form substantial fronds of acanthus-style leaves. Both here and in the patera immediately above, however, the leaves are convex, rather than concave, and between them, on the shaft’s centre-line, lies a vesica motif. The patera motif itself is framed around four radial fronds, with intermediate straight leaves, all carefully defined, and all grouped around a bold, hemispherical, central boss. The patera overlaps both the angle-rolls and the linear pattern of sub-circular mouldings that rise up the length of the shaft within them, to the cross-head, and underlie a second large patera, in mid-shaft, of similar design and dimensions to that lower down. On face C, the cross-head was decorated differently from face A. Here, the vertical mouldings of the shaft below are compressed into the curving shape of the lower cross-arm before emerging as symmetrical, convex, leaf-forms, that curve away from the cross-head’s centre, which appears entirely unsculpted.

At the surviving lower end of narrow face D, a moulded sub-octagonal base supports a narrow shaft of sub-octagonal section with a moulded sub-octagonal capital, supporting a table on which stands the carefully carved figure of a bishop in high relief. Although weathered and abraded, this has been a finely detailed and carefully moulded figure-sculpture. He wears a chasuble over an alb; but as the figure is missing its upper torso, no further detail of his episcopal vestments survives. The surviving upper part of the figure (from the neck upwards) shows what was once a well-modelled face, with rounded, almond-shaped eyes, defined pupils and other carefully depicted facial features. He wears a tall, fully detailed mitre, whilst to his left his crozier-head is wound in a tight spiral. Although the bishop’s head lies close to an area of damage, his mouth has clearly been carefully excised, using three carefully directed deep chisel blows (). Above the bishop, face D is otherwise undecorated.

Date and Iconography

The paterae on face C are clearly Romanesque design details, and such paterae frequently occur decorating Lincolnshire architectural components in the mid-12th century.Footnote107 More locally they occur, for example, on the tympanum of St John’s Duxford.Footnote108 They have also been noted on 12th-century cross-shafts, for example at both Aunsby 1 and Castle Bytham 2 (Lincolnshire), and at Swaffham Prior (Cambridgeshire).Footnote109 Tilbrook’s deployment of hieratic blessing bishop not only links it to Godmanchester (above), but generically to the Anglo-Scandinavian ‘high-cross’ figure-sculpture tradition we have already considered above in relation to Kings Ripton and Godmanchester. But the foliage details at Tilbrook must date it somewhat later than the Kings Ripton shaft, although they resemble those at both Hilton and Godmanchester. Indeed, the leaf-sculpture at Tilbrook has a recognizably ‘Transitional’ character; here leaf forms approaching stiff-leaf types are represented, and some of the architectural details—such as the semi-octagonal pedestal on which the bishop stands—must also suggest a date in the final quarter of the 12th century. More generally, the sparing surface decoration at Tilbrook, along with the use of surface mouldings to decorative effect, parallel developments in architecture of the late 12th century.Footnote110 Similar, though less sophisticated, ‘Transitional’ architectural motifs are also used to decorate the shafts at both Godmanchester and Hilton.

At Godmanchester, the comparable bishop figure is identified by inscription as Thomas Becket, whereas—strictly speaking—the identity of the episcopal figure at Tilbrook is unknown. At Tilbrook, however, circumstantial evidence suggests that this is also Becket, albeit that he carries a crozier, rather than the cross-staff that became a more standard attribute later.Footnote111 The bishop figure at Tilbrook must represent a saint, anyway, as the careful iconoclasm—erasing just the figure’s mouth—would only have been undertaken on a saintly image. Through its stylistic characteristics, then, Tilbrook might be dated to the final quarter of the 12th century, consistent with the suggestion that the bishop depicted is Becket.

Location and Patronage

We have argued that the Godmanchester cross’s patron might have been William de Mandeville, third earl of Essex, one of Henry II’s closest advisors and a prolific patron of the arts.Footnote112 Godmanchester was also, we propose, a public gesture—‘brazenly’ made—by a key member of Henry II’s entourage during the 1170s and 1180s, to associate himself with the new Becket cult, where the saint demonstrated support for the royal party in the successful siege of Huntingdon Castle in 1174.Footnote113 Consequently, William de Mandeville’s close connections with Tilbrook must also be of special interest to us. William’s Tilbrook manor was a subsidiary part of a large and valuable estate, subsequently based at the major adjacent manor of Kimbolton, the ownership of which in the late 12th century has been debated. Ann Charlton asserted that Kimbolton came into the de Mandeville estate only in 1189.Footnote114 Nevertheless, it must have been under William de Mandeville’s control between 1177 and 1185, in right of his niece’s custody, before she married Geoffrey fitz Piers in the latter year. Furthermore, William de Mandeville was the reported founder of Stonely Priory within the Kimbolton estate in 1180 and this seems to confirm his stewardship of the manor of Kimbolton in the late 1170s and 1180s.Footnote115

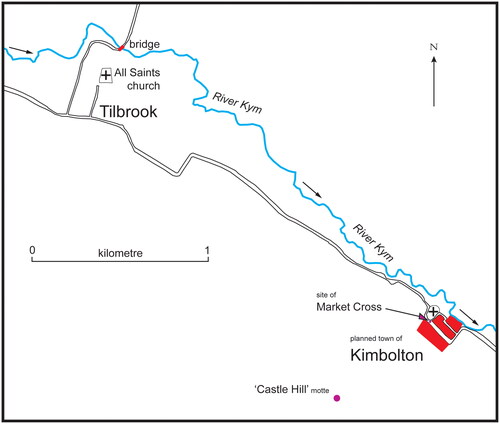

If, like the Godmanchester cross, that at Tilbrook commemorates Thomas Becket, we must ask whether it is likely that de Mandeville will have chosen a minor, secondary settlement such as Tilbrook for another demonstration of public penance. The major adjacent manor and new marketing centre at Kimbolton seems a much more likely location for such a public gesture ().

Fig. 13. Tilbrook and Kimbolton. Plan showing features mentioned in the text

Drawing and copyright authors

Unfortunately, we know little about Kimbolton at this period.Footnote116 It has been widely presumed that Geoffrey fitz Piers was the founder of the new planned town and market there, but this assumption appears based solely on King John’s market grant of about 1200.Footnote117 John Stratford pointed out that this grant was unlikely to represent the original stimulus for this major exercise in urban re-planning; more likely it was the culmination of that process. Consequently, he suggests, the process must have been underway for some time previously.Footnote118 Does the Tilbrook cross suggest that the initiative to found the town with its new planned market place began at Kimbolton under the lordship of William de Mandeville, two decades earlier? Was the shaft, with its possible commemoration of St Thomas, erected by de Mandeville to oversee the market of his newly established town at Kimbolton, as we have argued was the case at Godmanchester? There was indeed a great market cross at Kimbolton: a late-medieval record mentions that it was located near the north-western end of the broad market street.Footnote119 Kimbolton cross was replaced by a building known as Market Hall, said to have been built in 1603, rendering the masonry of the earlier cross available for recycling.Footnote120 Like the Kings Ripton shaft, its component stones might then have been carted, or floated, the two miles up the Kym to be reused in new abutments for Tilbrook bridge.

A further, more tangential, connection can be made between the Tilbrook monument and the former market cross at Kimbolton, through the careful and ‘informed’ iconoclasm it displays, whereby the mouth of the saint alone has been carefully chiselled away. It was believed that deleting the mouth or eyes of a saint would remove the power that saint held in this world, and such careful ‘informed’ iconoclasm was also in vogue at Kimbolton.Footnote121 The late-medieval painted screen at St Andrew’s Kimbolton also retains evidence of this distinctive type of iconoclastic attack. Although the entire heads of St Edmund and St Edward the Confessor have been carefully scrubbed out, the eyes of St Mary and St Anne have been delicately scored through and, just like the episcopal figure on the Tilbrook shaft, the image of St Michael has had only his mouth carefully scored out. Such iconoclastic precision is relatively unusual and is thought characteristic of attacks made in the mid-16th century, rather than during the Civil Wars.Footnote122 It is a mark of ‘learned’ iconoclasm—silencing the image, but leaving its silenced form visible as a sermon for the laity, in conformity with the condemnation of heathen idols in Psalm 115: ‘they have mouths but they speak not, eyes have they, but they see not’.Footnote123

Thus, a circumstantial argument can be made that the once-magnificent stone cross, now languishing in two parts at Tilbrook church, represents Kimbolton’s late-12th-century market cross. If that is correct, we can suggest that it was erected by William de Mandeville whilst he held the manor (1177–85), as a directly comparable act of public penance for his role in the martyrdom of Becket (and gratitude for the saint’s military intercession) to that he undertook when he raised the southern market cross at Godmanchester.

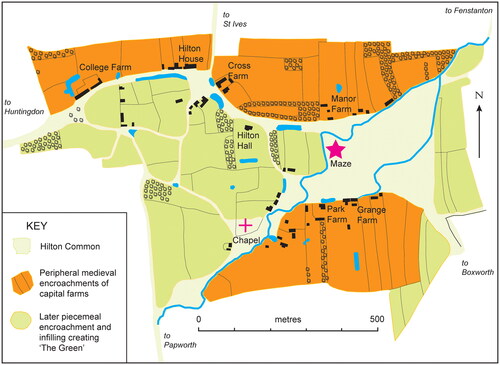

E) The Hilton Cross

Today, the head of the Hilton cross-shaft is mounted on a reused double-chamfered block against the west wall of the west tower of St Mary Magdalene’s church, Hilton, just north of the west door. It was rediscovered on 17 September 1904 during restoration of the tower under the direction of Sidney Inskip Ladds, where it had been reused as the top tread in the late-14th-century staircase.Footnote124

This cross-shaft, also made of Barnack stone, was somewhat smaller in scale than Godmanchester and Tilbrook/Kimbolton, but here the entire integral cross-head itself is preserved, along with a length of the slightly tapering shaft below (). Unfortunately, during incorporation into the tower staircase, it has lost approximately 30 mm thickness from the rear (face C), and it also suffered some mechanical damage. Nevertheless, the remaining faces, carved in low relief, survive moderately well. The shaft was already considerably weathered, when rediscovered, especially around the top sector of the head, suggesting that it stood outside for several centuries prior to the late 14th century.

Fig. 14. The Hilton cross fragment: a) surviving broad face A; b) right-hand narrow face B; c) left-hand narrow face D

Photos and copyright authors

The shaft’s surviving, gently tapering, broad face A () is decorated with neatly carved foliage: a central stalk throws off symmetrical leaves to both sides as it rises. These pairs of leaves are generically of acanthus-type and have three discrete, dished lobes of increasing length. As it approaches the cross-head, the stalk develops a single flower or bud, of four discrete symmetrically arranged lobes, and also of generic acanthus-like form. The cross-head itself is divided from the shaft below by its peripheral border moulding, reserving a circular panel at the head. Within, the cross-head is dominated by a delicately carved crucifixus, placed against a slightly raised but very narrow cross-form, with terminals of uncertain type. The crucifixus occupies most of the space available within the head. Christ’s suppedaneum has been largely removed by later mechanical damage, but he is dressed in a long loincloth and stands with knees slightly bent to his right. The torso is delicately articulated, with arms held out straight, palms towards the viewer. The head lolls to his right, and had finely detailed physiognomy, with beard and crown. There is no sign of iconoclasm here, indicating that the stone did not represent a post-Reformation repair to the tower staircase.

Narrow face D () has been damaged considerably. About 100 mm is missing from the lower part, along with the entire side adjoining face C. The face was originally decorated in two sculpted panels, however, with a column of early ‘dog-tooth’ motifs—four vesica-shaped ‘bay leaves’ leaning inwards to a raised central point, marked by a carefully drilled hole. The upper panel is occupied by a foliage stalk, reminiscent of that on face A, with a central stem throwing off symmetrical fronds to either side. As on face A, the central stalk terminates in a large, upwards-pointing bud or flower, composed of independent lobes; this extends beyond the shaft’s vertical face to continue onto the underside of the cross-head ring, which was otherwise undecorated.

Face B is more or less identical to face D () having also been truncated where it adjoins face C, and with its surviving panels decorated in the same manner, with a column of three ‘dog-tooth’ motifs set below another foliage stalk, less easily read, but mirroring face D.

Date and Iconography