Abstract

EARLY MEDIEVAL SWORDS have been a popular subject of historic and archaeological study in recent years. Swords have been found within the wealthiest early Anglo-Saxon furnished burials (the 5th–7th centuries ad) and have been recorded as highly decorated objects representing social status. From both archaeological and literary evidence, early medieval swords have been considered as likely ‘heirloom status objects’, curated and inherited over multiple generations. However, until recently there has been no direct study of the curation of swords. This is due to the problematic chronological nature of sword components, and because almost all are from burial contexts of the early Anglo-Saxon period. This study analysed graves containing swords from Kentish cemeteries of the 5th–7th centuries AD, and identified two examples of potential curation strategies through sword scabbard pieces chronologically older than the depositional context or individual within the grave. The evidence supports the belief that swords were recognisable heirlooms within early medieval communities, displaying the biography of the weapon, owner, and family. The recognition of an heirloom sword within a burial tableau would have been a socially noticeable action, affecting the collective memory of the mourners gathered at the funeral during a time of social and political stratification.

Résumé

Héritages « enfouis » : identification d’épées et de fourreaux conservés, déposés dans des sépultures du début du Moyen-Âge par Brian Costello

Les premières épées médiévales ont fait l’objet de plusieurs études historiques et archéologiques récentes. Des épées ont été retrouvées dans les plus riches sépultures mobilières de la période anglo-saxonne précoce (5e–7e siècles) et recensées en tant qu’objets très décorés, représentatifs d’un statut social. À partir d’éléments archéologiques et littéraires, les épées du début du Moyen-Âge ont été considérées comme de probables « objets ayant un statut patrimonial », qui étaient conservés et transmis au fil de plusieurs générations successives. Or, jusqu’à récemment, aucune étude n’avait été directement consacrée à la conservation des épées. Ceci s’expliquait du fait que la nature chronologique des composants d’épée posait problème et que, dans presque tous les cas, ils proviennent de contextes funéraires du début de la période anglo-saxonne. Cette étude a analysé des épées provenant de tombes de cimetières de la région du Kent datées des 5e-7e siècles et identifié deux exemples de stratégies potentielles de conservation, en l’occurrence des fragments de fourreau chronologiquement plus anciens par rapport au contexte des dépôts ou au défunt enseveli dans la tombe. Les éléments retrouvés appuient la conviction que les épées constituaient un patrimoine reconnaissable au sein des communautés du début du Moyen-Âge, mettant en évidence la biographie de l’arme, de son propriétaire et de la famille. La reconnaissance d’une épée patrimoniale au sein d’un tableau de sépulture aurait été une action socialement notable, affectant la mémoire collective des personnes rassemblées à l’occasion des funérailles à une époque de stratification sociale et politique.

Zussamenfassung

Verdeckte Erbstücke: Identifizierung kuratierter Schwerter und Schwertscheiden aus frühmittelalterlichen Bestattungen von Brian Costello

Frühmittelalterliche Schwerter waren in den letzten Jahren ein beliebtes Thema für historische und archäologische Studien. Schwerter wurden in den reichsten frühen angelsächsischen Gräbern mit Beigaben (5.-7. Jahrhundert n. Chr.) gefunden und als stark verzierte Objekte aufgezeichnet, die den sozialen Status repräsentieren. Sowohl aus archäologischen als auch aus literarischen Zeugnissen geht hervor, dass frühmittelalterliche Schwerter wahrscheinlich Erbstücke und Statusobjekte waren, die über mehrere Generationen hinweg kuratiert und vererbt wurden. Bis vor kurzem gab es jedoch keine direkte Studie über das Kuratieren von Schwertern. Das liegt an der problematischen chronologischen Natur der Schwertbestandteile und daran, dass fast alle aus Bestattungskontexten der frühen angelsächsischen Zeit stammen. In dieser Studie wurden Gräber mit Schwertern aus Friedhöfen in der englischen Grafschaft Kent aus dem 5. bis 7. Jahrhundert n. Chr. analysiert und zwei Beispiele für potenzielle Konservierungsstrategien anhand von Schwertscheidenstücken identifiziert, die chronologisch älter sind als der Ablagerungskontext oder die Person im Grab. Die Belege unterstützen die Annahme, dass Schwerter in frühmittelalterlichen Gemeinschaften erkennbare Erbstücke waren und die Biografie der Waffe, des Besitzers und der Familie widerspiegeln. Das Erkennen eines Erbstücks innerhalb eines Grabtableaus war höchstwahrscheinlich eine sozial auffällige Handlung, die das kollektive Gedächtnis der bei der Beerdigung versammelten Trauernden in einer Zeit der sozialen und politischen Schichtung beeinflusste.

Riassunto

Cimeli di famiglia sottotraccia: individuare spade e foderi conservati e depositati nelle sepolture altomedievali di Brian Costello

Negli ultimi anni, le spade altomedievali sono state frequente oggetto di studi storici e archeologici. Nei più ricchi corredi funerari del primo periodo anglosassone (V-VII sec. d.C.) si sono rinvenute spade descritte come oggetti riccamente ornati rappresentativi del rango di appartenenza. Dalle testimonianze sia archeologiche che letterarie le spade altomedievali venivano considerate ‘oggetti che avevano il valore di cimeli di famiglia’, quindi conservate ed ereditate nel corso di molteplici generazioni. Tuttavia fino a poco tempo fa non si è fatto uno studio diretto sulla conservazione delle spade. Questo è dovuto alla natura degli elementi che compongono la spada, cronologicamente problematici, e al fatto che quasi tutte le spade provengono da sepolture del primo periodo anglosassone. Questo studio analizza tombe di cimiteri del Kent del periodo dal V al VII sec. d.C. contenenti spade e identifica due esempi di potenziali strategie di conservazione mediante due pezzi del fodero della spada risalenti a un periodo cronologicamente precedente sia a quello dell’inumazione e che a quello dell’individuo sepolto. L’evidenza è a sostegno della convinzione che presso le comunità altomedievali la spada era un riconoscibile cimelio di famiglia che mostrava la biografia dell’arma, del suo proprietario e della famiglia di appartenenza. Nel contesto drammatico di una sepoltura, riconoscere la spada quale cimelio di famiglia doveva essere un evento di grande rilevanza sociale che avrebbe influito sulla memoria collettiva dei presenti al funerale in un periodo di stratificazione sociale e politica.

INTRODUCTION

Swords have received a large proportion of scholarly attention compared with other types of objects from early medieval north-western Europe. These weapons were symbols of social status (Davidson Citation1962; Kristoffersen Citation1999; Brunning Citation2019), with many elaborately decorated swords included as gravegoods within richly furnished early Anglo-Saxon burials (Carver Citation2000; Blackmore et al Citation2019). Scholarly studies of early medieval swords have focused on factors such as the interchangeable components of swords, position within graves, and their signification of elevated status (Davidson Citation1962; Hawkes and Page 1967; Menghin Citation1983; Brunning Citation2019; Sayer et al Citation2019). Through written records and recent archaeological studies, swords are interpreted as recognisable biographical objects, portraying their known histories and owners (Brunning Citation2019), and it has been acknowledged that swords were likely a chosen object type to continue in circulation as heirlooms (Brown Citation1915; Härke Citation2000; Ager et al Citation2006).

However, between the 5th and 7th centuries ad in southern and eastern Britain, swords are almost solely found within burial contexts, limiting our knowledge of how these items were circulated and curated in society (Härke Citation2000). Further problems arise from swords comprised of a mixture of older and later styled components, presenting some chronologically difficult and ambiguous objects for analysis (Dickinson Citation1977, 257–63; Brunning Citation2019, 83–5). The funerals of early medieval north-western Europe, which swords were occasionally included within burials, are understood to be times of social gathering, mourning and remembrance and were platforms for social negotiations and consolidating political stratification (Carver Citation2000; Lucy Citation2000; Halsall Citation2002; Williams Citation2006). The deposition of an heirloom during a funeral would have been a significant, public enactment, affecting the social remembrance of those gathered at the funeral (Williams Citation2006, 77; Costello and Williams Citation2019).

There have been examples of swords which have displayed ambiguous evidence of curation through a variety of parts of differing ages/typologies, referred to as the ‘Frankenstein effect’ (Dickinson Citation1977, 257–63; Brunning Citation2019). Other evidence is identifiable from disarticulated sword components, such as pommel caps, found in separate contexts or burials from the rest of the weapons (Parfitt and Anderson Citation2012, 51; Hills and Lucy Citation2013, 69), or from the unique case of the Staffordshire Hoard, which included a wide chronological spread of sword component types (Fern et al Citation2019). Combined, the evidence suggests that swords were composite objects and that their individual pieces were utilised as strategies to convey the biography of the sword within funerary rituals as mnemonic devices, with socially recognisable swords and/or recognisable sword pieces enacted as focal points within the grave tableau for the social remembrance of the mourners during the funeral (Costello and Williams Citation2019).

Through considering recent studies involving swords and early medieval burials (Klevnäs Citation2013; Brunning Citation2019; Fern et al Citation2019; Mortimer and Bunker Citation2019; Sayer et al Citation2019), this paper examines two burials with likely heirloom swords identified by older scabbard pieces. It has been suggested that certain components are thought to be favoured in written evidence, art, and surviving archaeological remains (Brunning Citation2019), however other components were still likely identifiable markers of the sword and its owners. The article addresses the funerary strategy of employing the heirloom status and biography of swords during the funeral, identified through their socially recognisability within daily life and during their final moments within the grave tableau.

THE STUDY OF HEIRLOOMS AND BIOGRAPHICAL OBJECTS

Baldwin Brown first inferred swords as heirlooms due to their low ratio of inclusion within early medieval burials, ‘the heirloom factor’ (Brown Citation1915), which has generally accepted throughout the study of the early Anglo-Saxon period. An heirloom is defined as ‘a valued object that has belonged to a family for several generations’ (OED 2022). The term heirloom originates from the two medieval English words heir, inheritor of property or rank, and lome, a tool (Lillios Citation1999, 241). However, the term has been used more fluidly to describe a variety of object-types across many different cultures (Lillios Citation1999). The curation and inheritance of material culture can convey vast amounts of socio-cultural information regarding familial and group structures and relations, gift exchange and the relationship with material culture (Mauss Citation1954; Appadurai Citation1986; Weiner Citation1992; Skeates Citation1995; Lillios Citation1999). Studies of various cultures’ heirlooms have investigated the interpersonal and personal investments of the objects, such as histories, memories, and emotional attachments of the family (Caple Citation2006, 205). Heirloom studies can indicate which types of objects were considered inalienable or were believed to have elevated value or importance to their owners (Gilchrist Citation2013, 2). Heirloom objects have also been utilised to display or differentiate social status during periods of social or political competition, such as the legitimacy of land claims (Komter Citation2001, 60; Wessman Citation2007, 71). These types of heirlooms were not available to all people, providing evidence of privilege or exclusivity (Lillios Citation1999, 236; Whitley Citation2002, 226).

In this sense, heirlooms are a subclass of biographical objects as their histories are known and connected to specific people, families, or kin groups (Lillios Citation1999). The biographical approach to objects can signify how they can accumulate their own histories over time, and in some cases become both well-known and mutually connected to the object owners (Kopytoff Citation1986; Gosden and Marshall Citation1999, 169; Holtorf Citation2008).

It has been suggested that the entries of heirlooms into the archaeological record could represent their loss of social importance (Lillios Citation1999, 257). However, in the context of burials of the 5th–7th centuries ad in southern and eastern Britain, the inclusion of important objects, such as heirlooms, signifies a noticeable statement during times of social gathering and remembrance (Williams Citation2006; Costello and Williams Citation2019). Furthermore, prevalent evidence indicates that the inalienability of swords necessitated their continuation within early Anglo-Saxon society ‘beyond burial’ (see Klevnas 2013). The visual presence of a known heirloom likely played a vital role within the heightened period of social stratification and competition of the 5th–7th centuries ad associated with the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of competing successor states (Arnold Citation1997; Fleming Citation2010). Therefore, the inclusion of a sword may have been necessary for its mnemonic role as a part of the funeral’s technology of remembrance (Williams Citation2006, 33), not simply through the act of deposition, but through the collective knowledge of its extended biography, negotiating, consolidating, or elevating the social legitimacy of the family after the conclusion of the burial. While Howard Williams (Citation2005) tackles this for early Anglo-Saxon cremation practices, this article engages with examples of swords with chronologically older components, specifically the scabbard, and the interpretation of their roles within early Anglo-Saxon inhumation burials.

EARLY MEDIEVAL SWORDS

Throughout historical and archaeological studies, early medieval swords have been understood as symbols of elevated status. Swords were consistently recorded as objects of wealth, as heirlooms, and as socially active within the interactions of people (Bazelmans Citation1999, 151; Brunning Citation2019, 125; Sayer et al Citation2019). Within the literature and poetry of the early medieval period, swords were named, attributed personhood and were described in great length and detail—sometimes more so than those who owned them (Sayer et al Citation2019, 544–5). Many swords within the epic poem Beowulf are described as heirlooms, frequently referred to as laf, an Old English word used interchangeably for both ‘sword’ and ‘heirloom’ (Sayer et al Citation2019, 545). Within early medieval poems such as Beowulf and The Battle of Maldon, the most valuable or famous swords tend to be described through their age as having been successful in combat, proving their reliability and worth to their wielders (Brunning Citation2019, 121; Sayer et al Citation2019, 545). The interchangeability of ‘sword’ and ‘heirloom’, and the highlighting of the age of the weapons as signs of trustworthiness correlates to the social importance of older or ancient swords.

Many of the later-Saxon wills of the 10th and 11th century ad also include descriptions of swords, either the monetary value of the weapon or its description or known history (Whitelock Citation1930; Härke Citation2000). Most of the wills involve the inheritance and gifting of wealth and land, but certain wills include very specific descriptions of swords, which implies that the named weapons were likely known. ‘The Will of the Aetheling Aethelstan’, includes the sword of the Mercian king Offa, which, although we don’t know whether it was truly a centuries-old weapon of the Mercian royalty, indicates the social importance and value of biographical swords (Whitelock Citation1930, 59). Another section of the same will bequeathed ‘the silver-hilted sword which belonged to Ulfketel’ (Whitelock Citation1930, 59). It is thought that Ulfketel was a person successful in combat against the Vikings, affirming the poetic evidence of the elevated value of old and ‘battle-tested’ swords (Whitelock Citation1930, 170; Sayer et al Citation2019, 545). Throughout the early medieval period, swords held an elevated status among other objects within the literary evidence, signifying their known biographies, martial ethos, and symbols of status within society.

Archaeological research has enriched and expanded considerably this understanding of early medieval swords. For instance, swords are almost only found within the furnished burials of the early Anglo-Saxon period (5th–7th centuries ad), as is most of the material culture from the period (Lucy Citation2000). These furnished burials (both cremations and inhumations) appeared in south-eastern Britain in the 5th century ad following migrations from continental north-western Europe after the collapse of the Roman imperial system (Lucy Citation2000; Fleming Citation2010). This period was a time of social reconstruction, competition and increased political stratification throughout the 5th and 6th centuries ad, followed by the consolidation of power and formation of the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms during the 7th century (Arnold Citation1997; Scull Citation1999, 21; Scull Citation2001). This is evident through the furnished burials excavated across lowland Britain since the late 18th century and many found during modern archaeological investigations. Thanks to generations of researchers, we now know that rather than a monolithic early Anglo-Saxon burial custom, the number, type, and quality of gravegoods were unequally distributed between graves throughout the 5th to 7th centuries. The furnishing of graves was a component of the funerary ritual organised and constructed most likely by the family or relations of the deceased (Williams Citation2006; Welch Citation2011, 266; Sayer Citation2020). The dead were adorned with selected clothing and objects in order to create and convey an idealised, socially remembered identity of the deceased and their families (Härke Citation1997; Halsall Citation2002; Williams Citation2006; Devlin Citation2007, 35; Sayer and Williams Citation2009, 20–1; Sayer Citation2020). These objects were enacted as mnemonic devices during funerary rituals, visually engaging with the mourners to depict, reconstruct, or transform the identity of the deceased. It is interpreted that this was a stratagem for the improvement of the surviving family’s social standing; and utilised as a focal point in which past events, people, myths and legends were socially remembered (Carver Citation2000; Williams Citation2006, 40; Devlin Citation2007, 35). These funerals, the gathering of people, and the visual tableau of objects within the grave are understood as a vital platform for social competition and political stratification during the early Anglo-Saxon period (Halsall Citation1995; Scull Citation1999, 21; Carver Citation2000, 40; Semple Citation2008, 408). The objects deposited within the burials across southern and eastern Britain during the 5th–7th centuries ad were generally ‘gendered’ by type; with dress accessories such as brooches and necklaces as the main object types of the female gendered burials, and martial objects like shields, spears, and in rare occasions, swords most often associated with male-gendered burial assemblages (Härke Citation1989; Stoodley Citation1999; Lucy Citation2000).

The swords of the early Anglo-Saxon period are a cohesive type found across north-western Europe during the 4th to 8th centuries ad (Fischer et al Citation2013, 110). Compared with other martial objects such as shields or spears, swords appear within burials in the lowest ratio indicating a rarity within society of this period (Härke Citation1989; Stoodley Citation1999). Their deposition within burials of the most prestigious male-sexed graves, such as Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk (Carver Citation2000) and the Prittlewell chamber burial, Essex (Blackmore et al Citation2019), reinforced the interpretation of swords as objects of high social status. The materiality of swords added to this interpretation, with many being forged to display pattern-welded designs within the blade (Gilmour Citation2007), hilts adorned with precious metals and stones, such as gold, silver, and garnets (Davidson Citation1962; Brunning Citation2019), and scabbards with their own decorated front plates and fittings (Cameron Citation2000).

Early medieval swords are classified as ‘long swords’ with blades ranging between 75 and 95 cm (Gilmour Citation2007, 92), and are characterised by the interchangeability of their components, such as the hilt, scabbard, and belt fittings (Fischer et al Citation2013; Brunning Citation2019, 61). Several swords potentially portrayed rank through rings attached to either their guards or pommels. Known as ‘ring-swords’, these appeared in north-western Europe between the 6th and 8th centuries ad and are believed to represent retainer status or fealty to a lord or king, which would signify certain roles and social ranks among the sword-owning elites (Evison Citation1967, 63; Steuer Citation1987, 203–5; Brunning Citation2019, 50).

Initial studies of early medieval swords originated on the Continent with Ellis Behmer’s analyses and catalogue of swords focused upon the hilt, scabbard, and sword blades (1939). Hilda Ellis Davidson was the first to discuss swords within Anglo-Saxon England through their materiality, archaeological contexts, and within written records (1962), followed by Vera Evison’s study on ring-swords discovered within Britain (1967). Wilfried Menghin’s (Citation1983) research continued to catalogue and categorise sword components and his typologies are still utilised today.

Esther Cameron’s analysis of early medieval scabbards and fittings was a much-needed addition to the study of sword-component typologies and is still one of the very few pieces of research which directly highlighted the significant detail and individuality of the sword components (Cameron Citation2000). Cameron identified certain traits in the preserved organic components and metal fittings of scabbards indicating chronological trends, such as the construction of the wooden scabbard plates, or changes in the use of certain scabbard mouth bands (2000, 35–41, ). The preserved organic scabbard remains also revealed significant decorative techniques created and visible upon them (Cameron Citation2000, 39–40).

FIG 1 Example of a copper-alloy scabbard mouth band from the cemetery of Riseley, Horton Kirby, grave 75 (scale: 66 mm × 19 mm). Photograph by author, courtesy of the Dartford Museum.

These typological studies have revealed several issues in the study of swords from the early medieval period. Firstly, swords are almost solely discovered within mortuary contexts, and were deposited in generally small numbers than other types of weapons assemblage objects. Secondly, the interchangeability of physical components has presented chronological challenges to accurate dating as many of these swords were in use over extensive periods of time. Preservation has also caused issues in interpretation. In most cases, the excavated iron blades are severely corroded and organic hilt or scabbard fittings rarely survive, providing little information. The metal hilt and scabbard fittings survive better and are more suited for chronological study. Metal hilt fittings of swords were constructed from softer metals such as copper alloy, silver, and gold which survive better than iron within the archaeological record. Very few have been found in Britain with surviving, intact organic components, such as bone or antler grips or guards, or leather or wooden scabbards (Filmer-Sankey and Pestell Citation2001: 107). This has prevented the further analysis of most excavated swords and has complicated typological chronologies and curation identification due to the even smaller sample size of surviving hilt fittings.

Sword wear and modification

More recently, the multidisciplinary work by Sue Brunning analysed the role of swords within early medieval society (2019). Most notably, Brunning (Citation2019, 62) identified asymmetrical abrasion upon sword hilts, specifically pommel caps and the upper guard, indicating the daily adornment of the weapon upon the belt during life. This suggests that swords worn daily would likely be publicly recognised within their communities. Furthermore, the identification of swords with evidence of repairs, modifications or combinations of component types, such as aged components, have been interpreted as signs of curation. It has been identified that certain swords were assembled using pieces from other swords displaying a mixing of styles and ages present what has been called the ‘Frankenstein’ effect (Brunning Citation2019, 83). Examples of the ‘Frankenstein’ swords from Brighthampton (Oxfordshire) grave 31 (Dickinson Citation1977) and the sword from Blacknall Field (Pewsey, Wiltshire) grave 22 (Annable et al Citation2010, 10–11) both display sword fittings with noticeable chronological differences (Brunning Citation2019, 83). The factors of abrasion and modification of swords highlight their recognisable characteristics reflecting upon the people and events in which the objects were present at and involved in (Brunning Citation2019, 139). The possession of a biographical status object such as a sword would also reflect on their wielders.

Grave re-opening

Another recent archaeological study has indicated the importance of swords within early Anglo-Saxon society demonstrated by the need for their continued circulation. It has been found that during the 5th to 7th centuries AD, the practice of re-opening of graves to reclaim objects was prevalent across most of north-western Europe (Klevnäs Citation2013, Citation2015; Noterman Citation2021). Prior to Klevnäs’ research, it was thought that the re-opening of graves was less prevalent in Britain compared to early medieval continental cemeteries. However, Klevnäs demonstrated that grave re-opening did occur in early Anglo-Saxon England, with the majority taking place in Kent. Notably, she postulates that much of this re-opening took place soon after burial, perhaps within a decade (Klevnäs Citation2013, Citation2015, 160).

Earlier interpretations of grave re-opening attributed the practice to religious beliefs, conflict between social groups, or the robbery of valuable objects or raw materials. However, no evidence has been found supporting any of these interpretations (Klevnäs Citation2015, 160; Noterman Citation2021). Klevnäs’ research has discovered that specific graves were targeted with only two types of sought-after objects: swords and brooches (Klevnäs Citation2015, 166). The specific removal of these objects, swords from male-sexed graves and brooches from female-sexed graves, was identified within disturbed graves containing metal staining in the soil or on the skeleton signifying the former presence of the removed object (Klevnäs Citation2015, 162–3). The targeting of these objects was also indicated by other valuable objects left within the re-opened graves (Klevnäs Citation2013, 163). Graves containing swords are usually accompanied by other weapon objects, such as shields and spears (Härke Citation1989), but only swords were targeted and taken. Klevnäs has indicated that both swords and brooches had a much more important and symbolic function than previously believed (2015, 165). Fragmented pieces of rusted iron from sword blades or tangs remaining within graves indicate that some swords were corroded when they were retrieved (Klevnäs Citation2013, 12). Klevnäs attributes the social importance of the possession of these objects, no matter their state of preservation, as a form of ‘keeping while giving’ through their original display and deposition in the funeral, then later reclamation (Klevnäs Citation2015, 171).

The Staffordshire Hoard

The discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009 revealed a unique archaeological context including a majority of disarticulated sword fittings deposited together within the latter half of the 7th century ad (Fern et al Citation2019). The chronology of the hoard material spanned the mid-6th to mid-7th century ad (Fischer and Soulat Citation2011; Fern et al Citation2019, 270), signifying that the earliest pieces had an extended period of use and circulation, whether on their original sword or attached to later weapons as seen in examples previously discussed. Some of the 6th-century early objects like pommel 68, a silver and heavily abraded Scandinavian hybrid type Bifrons-Gilton/Beckam-Vallstenarum pommel (Fern et al Citation2019, 263), would likely contain a recognisable and known biography extending over multiple generations (). The notable chronological disparities within the Staffordshire Hoard provide further evidence of the curation of swords or their components.

FIG 2 Pommel 68 from the Staffordshire Hoard.

Arrows (added by author) highlighting extensive abrasion and damage (scale: 49 mm × 16 mm × 18 mm). Photograph courtesy of Howard Williams.

The evidence from studies of abrasion patterns and modifications (Brunning Citation2019) and the retrieval of swords from the process of grave re-opening (Klevnäs Citation2013) indicates a social elevation and continued circulation of swords within early medieval communities. Asymmetrical abrasion patterns have provided evidence of the daily or consistent adornment of the swords, signifying their identifiability and active roles within society (Brunning Citation2019). The immense effort in re-opening graves to specifically gain access to these swords potentially reveals the necessity of the objects to continue roles within society, and the reluctance to leave them with the deceased (Klevnäs Citation2013). These studies raise new questions on the significance of sword deposition within graves. Grave re-openings happened in specific certain localities, such as the Isle of Thanet and surrounding vicinity in Kent, with many other areas including undisturbed sword burials (Klevnäs Citation2013). It is within these undisturbed sword burials that curation can be adequately identified.

THE IDENTIFICATION OF HEIRLOOM SWORDS

Much of the previous scholarship on early medieval swords has focused on hilt fittings to understand their chronology (Menghin Citation1983; Brunning Citation2019; Sayer et al Citation2019), but many swords have been excavated with no surviving hilt fittings. This is attributed to the decomposition of organic materials, such as horn or ivory hilt pieces, which many swords contained (Ager et al Citation2006; Ager Citation2012; O’Connor et al 2015; Brunning Citation2019, 61). However, in a number of cases it has been noted that scabbards and their various pieces are chronologically older than the grave context within which the sword is deposited. Cameron’s research on sword scabbards (2000) significantly progressed the understanding of their construction, use, and chronologies. The style of wooden face plates, type of metal fittings, length of fleece lining fibre, and decorations all have exhibited chronological patterns. Scabbards, just like hilt fittings, have been found displaying modifications and repairs, and refurbishments along with decorations upon both the metal fittings and organic scabbard plates (Cameron Citation2000, 34–5, 73–4).

It is also a significant finding that scabbards were constructed specifically for each sword, with surviving evidence indicating perfect fits between the blade and scabbard at such cemeteries as Deal, Kent and Snape, Suffolk (Cameron Citation2000, 35). This may indicate that swords excavated from burials with evidence of scabbards were specifically made for that blade. A few examples containing chronologically older scabbard fittings have been found, though the discussion of their curation still remains ambiguous due to their respective grave contexts. Grave 22 from the cemetery of Blacknall Field, Pewsey contained a scabbard mouth of Menghin’s Altenerding-Brighthampton-type which noticeably pre-dated the rest of the sword fittings and grave assemblages by several generations (Menghin Citation1983; Annable et al Citation2010, 9–11). A similar example was found in the cemetery of Petersfinger (Wiltshire): Grave XXI, where an older scabbard was paired with a more recent sword (Dickinson Citation1977, 257).

A recent study tested a method to identify characteristics of curation among swords and brooches in early Anglo-Saxon burials (Costello Citation2020). The study examined 61 burial contexts containing swords from 13 cemeteries of early Anglo-Saxon Kent (5th–7th century ad) were analysed to identify heirloom swords (Costello Citation2020; see ). The early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries of Kent were ‘wealthier’ with a larger proportion of gravegoods compared to other Anglo-Saxon regions of the 5th–7th centuries (Sayer Citation2010, 70), including a higher ratio of burials containing swords, at approximately 20% of the weapons assemblage burials in comparison to 11% in other regions (Härke Citation1989, 54; 1992; Gilmour Citation2010). Early medieval Kent was the first Anglo-Saxon kingdom recorded at the start of the 7th century ad, with the Law of Aethelberht one of the first written sources of the period, dated to 602/3 ad (Oliver Citation2002, 8; Reilly Citation2004; Welch Citation2007, 190). The practice of property inheritance after the death of a family member was apparent within these law codes, providing evidence of the likelihood for heirloom status objects (Härke Citation2000; Oliver Citation2002, 79).

To identify the continued circulation or deposition of heirloom swords, sword burials were analysed for chronological disparities between objects, abrasion and wear between materials and the approximate age of the deceased. Of the 61 graves containing swords, only two contained identifiably curated objects, both through the metal scabbard mouth: Buckland, Dover, grave 96B and Saltwood Tunnel, Folkstone, grave C3779 (Costello Citation2020, 251). Older scabbard mouths have been found with later swords in other early medieval cemeteries, such as in grave 22 in Blacknall Field, Pewsey (Annable et al Citation2010, 10). Many other graves displayed partial evidence of curation, but due to poor skeletal or grave context preservation and differing excavation and recording techniques, confident identification of heirloom status was unattainable.

The cemetery at Buckland was excavated in two phases: the first in 1951 (Evison Citation1987) and second in 1994 (Parfitt and Anderson Citation2012), revealing a total of 431 graves dated to the late 5th- to 7th centuries ad (Evison Citation1987; Parfitt and Anderson Citation2012). The cemetery contained a total of 24 swords, with two discovered prior to the excavation without contextual recording which excluded them from further investigation (Evison Citation1987, 15). The cemetery group at Saltwood Tunnel, excavated between 1991 and 2001, was in actuality three proximal cemetery groups, each focused around a Bronze Age barrow (Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006, 26). A total of 217 graves were within the cemetery group, dating from the 6th to 7th centuries (Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006, 27), which included 11 burials containing swords (Ager et al Citation2006, 4). Both cemeteries included a variety of elaborate graves, both in the number, type and quality of objects, along with grave constructions. Given also that these cemeteries were two of the largest case studies of the sample, it has been interpreted that both mortuary landscapes were locations of social negotiations and political competition conducted through the funerary rituals (Scull Citation1999, Citation2001).

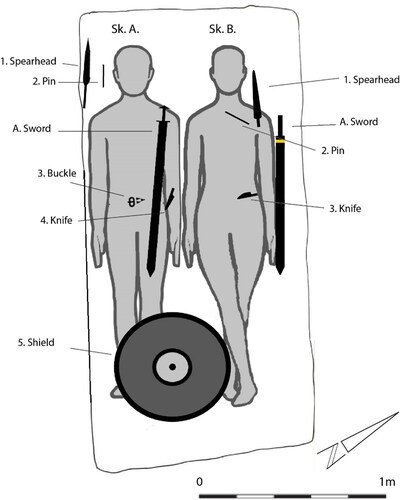

Buckland 96 was a unique grave context compared with all other Anglo-Saxon burials, being a double sword burial accompanying an adult male and a possible female (Evison Citation1987, 239; Lucy Citation1997, 161). The individuals were placed in the supine position within the grave with each sword along the left side of the body, hilt near the top of the humerus (). The left skeleton (96 A) was an adult male aged over 40 years at the time of death. The skeleton on the right (96B) was sexed as a possible female, between the ages of 20 and 30 years at the time of death (Evison Citation1987, 124–6; Lucy Citation1997, 161). The gravegoods indicated an early 7th-century ad date for the burial, with only the scabbard mouth of the sword from 96B dating earlier. The scabbard mouth of this sword is of Menghin’s type Kempston-Mitcham and use was dated to the 6th century ad (Menghin Citation1983; Cameron Citation2000; Koch Citation2001). The hilt of the sword had a faceted tang end, implying a likely organic pommel or an absent metal pommel (Menghin Citation1983; Parfitt and Anderson Citation2012; Bayliss and Hines Citation2013, 183). The sword of 96 A had a 7th-century long iron pommel and silver-plated upper and lower guards. It also had a plain silver scabbard mouth band, which also suggests a 7th-century ad date (Menghin Citation1983; Cameron Citation2000, 43; Bayliss and Hines Citation2013). As it has been shown that swords usually are deposited with adult burials (Härke Citation1989; Stoodley Citation1999), 96B falls into the youngest age category provided with a sword burial. With a 6th-century scabbard mouth band in a 7th-century grave, the sword was likely owned by a previous individual before 96B came of sword-owning age. This indicates the curation and inheritance of the sword, signifying more than one owner and an extended, complex biography of the object. Its visible presence during the funeral of a unique, double sword grave would have a likely impactful mnemonic effect upon the social remembrance of the mourners gathered during the funeral.

FIG 4 Recreation of Buckland grave 96 including heirloom sword with individual Sk. B.

Base excavation re-drawn after EvisonCitation1987, fig 77.

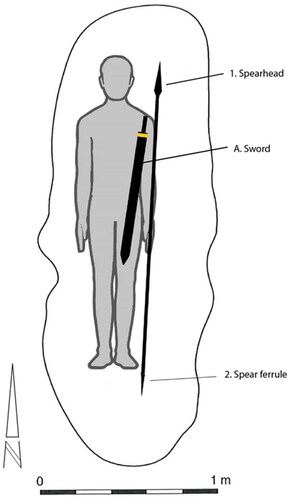

Saltwood, grave C3779 was similar to the curation found in Buckland 96B. The grave contained an osteologically sexed male, aged between 20 and 30 years at the time of death and was located in a Bronze Age barrow within the western group of the cemetery, dated to the late 6th to the first quarter of the 7th century ad (Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006, 62). The burial did not contain many gravegoods in comparison with most sword graves (Härke Citation1989), only the sword cradled in the left arm and a spear of Swanton’s type F2, dated to the late 6th to early 7th century ad running down the left side of the body (Swanton Citation1974; Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006, 28; ). The blade of the sword has been interpreted as a ‘lesser developed’ form of pattern-welding, with no forging of composite intertwining of the iron rods, as seen in other pattern-welded blades (Gilmour Citation2010, 68), but styled comparably to water-like patterns similar to that of Iron Age swords (Gilmour Citation2010, 67–8).

FIG 5 Recreation of Saltwood Tunnel grave C3779.

Base excavation plan re-drawn after Riddler and TrevarthenCitation2006, fig 88.

The hilt of the sword included an iron button pommel which likely attached to a larger organic piece, copper-alloy grip mounts, and a copper-alloy scabbard mouth. The trapezoidal grip mount was identified by X-ray on one side, and it is believed that the other side only partially remains (Ager et al Citation2006, 9). Sword grip mounts are a rare find in Anglo-Saxon England though more common on the Continent (Ager et al Citation2006, 9). The mount from the sword hilt in grave C3779 is similar to Menghin’s Snartemo-Roes type, the Scandinavian form used throughout the 5th to 7th centuries ad (Menghin Citation1983; Ager et al Citation2006, 9).

The sword’s scabbard mouth was one of two discovered within the Saltwood Tunnel sample. Five others also contained evidence of organic scabbard mouths of woven braids (Ager et al Citation2006, 10). The scabbard mouth band is the same Menghin’s Kempston-Mitcham type as grave 96B of Buckland, dated to the 6th century ad (Menghin Citation1983; Cameron Citation2000). It is believed that this scabbard mouth was gilded, but heavy corrosion did not leave any evidence of gilding upon the piece (Cameron Citation2000, 17).

Like Buckland grave 96B, Saltwood grave C3779 included a 6th-century ad scabbard piece within a likely 7th-century ad grave. The individual was also of the younger age group of those buried with swords, between 20 and 30 years old, suggesting the sword was an heirloom. In comparison with the other sword graves within the Saltwood cemetery, this grave had the least amount of gravegoods or furnishings. As the sword was believed to have been owned by a previous individual, the weapon’s extended biography was likely utilised as a focal point for the funerary rituals. Unlike other wealthy or elaborately presented burials, the focus of those gathered at the funeral would have centred around the known history of the weapon and its owners.

DISCUSSION

The curation of early medieval swords has always been presumed but their problematic nature made identifying heirloom swords difficult. This study tested a method in an effort to identify the curation of swords deposited within burials. Though the methods were limited due to the preservation and adequacy of the grave context, it was successful in highlighting two cases within the 61 sword burials analysed. Others had aspects of curation and may have been heirloom swords, however, there was not enough evidence for them to be confidently identified.

The two graves discussed within this research highlighted likely curated scabbard mouth pieces: Buckland Grave 96B and Saltwood Tunnel Grave W3779 (Evison Citation1987; Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006). Both graves are dated to the end of the 6th and into the 7th century ad (Evison Citation1987; Riddler and Trevarthen Citation2006) but included scabbard mouths of Menghin’s 6th-century Kempston-Mitcham type (Menghin Citation1983; Evison Citation1987; Ager et al Citation2006; Cameron Citation2000, 42–3). Both individuals buried with swords were on the younger side of those commonly attributed swords within graves, between 20-30, which suggests that these scabbard pieces were previously owned and used by another individual. Usually, an object dated to be in use throughout the 6th century wouldn’t receive significant attention within an early 7th-century burial. However, given the scabbard’s 6th-century date and inclusion within the early 7th-century burial of the two individuals aged 20–30, these swords were owned by a previous individual.

These swords were chosen to accompany the dead by their family or wider kin group. The deployment of these notable objects, with their extended biographies, would have been a noticeable focal point for those gathered at the graveside for the funeral. Both of these cemeteries, Dover and Saltwood, indicate a large populace of multiple families and communities using the location to bury their dead. The inequality of gravegoods throughout the cemeteries highlights the socially competitive nature of the mortuary landscape (Scull Citation1999, Citation2001). The use of an heirloom would have been a rare and effective tactic, differing from other displays of status and/or identity. The key feature of an heirloom is the connection to previous individuals and the events at which the object and owner were present. This allows the presence of the object to provide a mnemonic device in which the past stories can be remembered by the mourners of the object, its previous owners, and the deceased with whom it accompanies.

Another aspect of the inclusion of these heirlooms is the display of the family or kin throughout the funeral. An heirloom sword can be interpreted as a physical object representing a genealogy or family line, along with elevated status. As previously discussed, the written record of heirloom swords carries the knowledge of the previous owners, as the weapon accrues a biography from its extended circulation. The inclusion of an heirloom sword within a burial suggests the importance of the family or kin group, rather than just the identity of the deceased. Its connections to others may provide a basis for the family to distinguish themselves during this period of social competition. With recent studies of families, kinship and new discoveries through ancient DNA analysis (Sayer Citation2020; Gretzinger et al Citation2022), it is clear that early medieval Europe involved extensive social complexities, which can be understood through the performances of material culture and furnished burials.

The evidence of the two heirloom graves, Dover 96 and Saltwood W3779, suggest this strategy of heirloom use. Both graves were not elaborately furnished but were likely socially notable and memorable by other means. The double sword burial of a male and possible female alone is a unique aspect not found elsewhere. The mature adult male, 96 A, with a complete set of martial regalia of a shield, spear, and sword signified a level of elevated status. The younger possible female skeleton, 96B, buried with the older of the two swords potentially implied a connection and display to the wider family in which they belonged. This is similar with Saltwood W3779, as this adult was the least furnished of all the sword burials in the cemetery. The inclusion of the recognisable curated sword would highlight the individual’s connection to further relations, both deceased and still living within their community.

It is significant that when identifiable, all swords within the sample displayed evidence that they were buried within their scabbards. Cameron identified that the uniformity of design and construction indicates not only the likelihood of dedicated manufacture of the scabbards, but also revealed individuality through metal fittings, bindings, and other forms of decoration, suggesting unique and recognisable aesthetic qualities of the objects (Cameron Citation2000, 73–4). Like the interchangeable pieces of the sword hilt, scabbards that have undergone refurbishment and the fitting of different components have also been found (Cameron Citation2000, 34; Brunning Citation2019, 83–5). Therefore, scabbards were potentially as identifiable as the hilts of swords, suggesting their ability to display the biography of the sword and sword-wielder.

These examples of heirloom swords from early medieval Kent provide further evidence and understanding of the weapon type across northwest Europe. Swords were composite objects made up of interchangeable parts, where each piece could represent the weapon as a whole, along with biographies of past swords and owners. Examples of ‘Frankenstein’ swords presented individual histories through each additional attachment, culminating in the extended identity of the sword. The sword from Brighthampton 31 reflects this, fitted with a combination of Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon components from the 5th to 6th century AD, along with uniquely recognisable scabbard fittings of the mouth band and decorated chape (Dickinson Citation1977, 279). This reflects similarly in the identified heirloom swords in Buckland 96b and Saltwood W3779, specifically within the grave context. Whether the scabbard mouths of these swords were additions or original pieces, they conveyed and connected the deceased with biographies of the previous sword owners. Taking into consideration examples of disarticulated sword pieces within burials, such as the pommel caps found within Dover 360 (Parfitt and Anderson Citation2012, 51) and Spong Hill (Norfolk) cremation C1105 (Hills and Lucy Citation2013, 69), and various examples of refurbished and modified swords of various aged pieces (Brunning Citation2019, 78–88), each individual piece may represent the previous swords of which they formed part. This then presents early medieval swords of Europe as containing multiple biographies in appearance and recognisability.

The identification of heirloom swords within burials does raise further questions on the social complexity and recognisability of individual sword components across early medieval Europe. Were contexts such as the deliberate burial of the collected elaborate sword fittings within the Staffordshire Hoard (Fern et al Citation2019), and the ‘killed’ swords through bending and twisting of the blades in south-eastern Viking-Age Norway (Aannestad Citation2018), an effort to remove known biographies, histories, or even genealogies from continued circulation? This further reveals the significance of swords being one of two object types targeted and retrieved in the re-opening of graves across many areas of northwestern Europe (Klevnäs Citation2013; Noterman Citation2021). The necessity to claim specific swords through this practice alludes to social roles still waiting to be discovered.

CONCLUSION

Evidence from early medieval literature has highlighted swords as heirlooms and socially active and culturally important objects. Yet the archaeological evidence from the early medieval period presents a situation where heirloom swords have always been difficult to identity. However, this paper has tested a method using grave contexts to identify chronologically older swords, or heirlooms, deposited within burials. As scabbards were found to be constructed specifically for its own unique swords, the examples provided indicate that heirloom swords were in fact included within burial tableau. However, if these scabbards were refurbished using older components, the visible recognition and biography of the fittings would likely be known additions to the biography of the weapon as a whole.

During the heightened time of social negotiations and political stratification within the 6th and early 7th centuries ad (Scull Citation1999), the inclusion and presence of the sword within the grave tableau was a key, impactful feature for the people gathered for the funeral. This study used examples from early medieval Kent, but is applicable across northwestern Europe, where furnished burials utilising swords also signify familial and social negotiations (Halsall Citation1995, Citation2002). These examples of heirloom swords were employed as a strategy to display of the deceased and the wider family’s prominent or elevated status, employing the weapon’s biography as a mnemonic device as a recognisable focal point for the social remembrance to the mourners (Williams Citation2005, Citation2006).

Swords were composite objects, which could present multiple biographies and histories through the attachment of various fittings. Historical literature depicts heirloom swords containing recognisable components conveyed as genealogies. The deposition of heirloom swords within burials was a specific act chosen by families and kin groups to affect their political relationships with neighbouring groups at the gathering for the funeral. With recent studies of families, kinship, ancient DNA analysis and new findings on early medieval migrations (Sayer Citation2020; Gretzinger et al Citation2022), the identification and analysis of the curation of material culture can reveal the processes and practices used to navigate the social complexities between groups in early medieval Europe.

| Abbreviations | ||

| CTRL | = | Channel Tunnel Rail Link |

| OLA | = | Museum of London Archaeology |

| OED | = | Oxford English Dictionary |

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Howard Williams and Paul Mortimer for their thoughts and comments on the topics of this research. Also to be thanked is Reanna Phillips for her extensive help throughout the research process.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Aannestad, H L 2018, ‘Charisma, violence and weapons: The broken swords of the Vikings’, in M Vedeler, I M Røstad, E S Kristoffersen (eds), Charismatic Objects: From Roman Times to the Middle Ages, Oslo: Cappelen Damm AS.

- Ager, B M 2012, ‘Swords’, in K Parfitt and T Anderson (eds), Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, Ashford: Canterbury Archaeological Trust, 49–52.

- Ager, B M, Cameron, E, Riddler, I et al 2006, Early Anglo-Saxon Weaponry from Saltwood Tunnel, CTRL Specialist Report Series. London: London and Continental Railways Oxford Wessex Archaeology Joint Venture.

- Annable, F K, Eagles, B N and Ager, B 2010, The Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Blacknall Field, Pewsey, Wiltshire, Wiltshire Archaeol Nat Hist Soc, Trowbridge: Cromwell Press.

- Appadurai, A 1986, The Social Life of Things; Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arnold, C J 1997, An Archaeology of Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, 2nd edn,. London: Routledge.

- Bayliss, A and Hines, J 2013, Anglo-Saxon Graves and Grave Goods of the 6th and 7th Centuries AD: A Chronological Framework, Wakefield: Society for Medieval Archaeology.

- Bazelmans, J 1999, By Weapons Made Worthy, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

- Behmer, E 1939, Das zweischneidige Schwert der germanischen Völkerwanderungszeit (Unpublished PhD Thesis, Stockholm University). Stockholm: Tryckeriaktiebolaget Svea.

- Blackmore, L, Blair, I and Hirst, S 2019, The Prittlewell Princely Burial: Excavations at Priory Crescent, Southend-on-Sea, Essex, 2003, London: MOLA.

- Brown, G B 1915, The Arts in Early England: Vol 3 Saxon Art and Industry in the Pagan Period, New York: Dutton.

- Brunning, S 2019, The Sword in Early Medieval Europe. Experience, Identity, Representation, Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Cameron, E 2000, Sheaths and Scabbards in England ad 400–1100, Oxford, British Archaeological Report B301.

- Caple, C 2006, Objects: Reluctant Witnesses to the Past, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Carver, M 2000, ‘Burial as poetry: The context of treasure in Anglo-Saxon graves’, in E M Tyler (ed), Treasure in the Medieval West, York: York Medieval Press, 25–48.

- Costello, B 2020, The Heirloom Factor Revisited: Curated Objects and Social Memory in Early Medieval Mortuary Practices (unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Chester).

- Costello, B and Williams, H 2019, ‘Rethinking early medieval heirlooms’, in M Knight, D Boughton and R Wilkinson (eds), Objects of the past in the past: Investigating the Significance of Earlier Artefacts in Later Contexts, Oxford: Archaeopress, 115–30.

- Davidson, H E 1962, The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England: Its Archaeology and Literature, Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Devlin, Z 2007, Remembering the Dead in Anglo-Saxon England: Memory Theory in Archaeology and History, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Dickinson, T M 1977, The Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites of the Upper Thames Region, and their Bearing on the History of Wessex, Circa ad 400–700 (unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Oxford).

- Evison, V I 1967, ‘The Dover ring-sword and other sword-rings and beads’, Archaeologia 101, 63–118.

- Evison, V I 1987, Dover: The Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, London: Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England.

- Fern, C, Dickinson, T and Webster, L 2019, The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure, London: Society of Antiquaries of London.

- Filmer-Sankey, W and Pestell, T 2001, Snape Anglo-Saxon Cemetery: Excavations and Surveys 1824–1992, Ipswich: Environment and Transport, Suffolk County Council.

- Fischer, S and Soulat, S 2011, ‘The typochronology of sword pommels from the Staffordshire Hoard’, in Papers from the Staffordshire Hoard Symposium, London: British Museum.

- Fischer, S, Soulat, S and Fischer, T 2013, ‘Sword parts and their depositional contexts-symbols in migration and merovingian period martial society’, Fornvännen 108:2, 109–22.

- Fleming, R 2010, Britain after Rome: The Fall and Rise, 400 to 1070, London: Penguin.

- Gilchrist, R 2013, ‘The materiality of medieval heirlooms: from sacred to biographical objects’, in H P Hahn and H Weiss (eds), Mobility, Meaning and Transformation of Things. Shifting Contexts of Material Culture through Time and Space, Oxford: Oxbow Books, 170–82.

- Gilmour, B 2007, ‘Swords, seaxes, and Saxons: Pattern-welding and edged weapon technology from late Roman Britain to Anglo-Saxon England’, in M Henig and J T Smith (eds), Collectanea Antiqua: Essays in Memory of Sonia Chadwick Hawkes, Oxford, British Archaeological Report 1673.

- Gilmour, B 2010, ‘Ethnic identity and the origins, purpose and occurrence of pattern-welded swords in sixth-century Kent: The case of the Saltwood cemetery’, in M Henig and N Ramsey (eds), The Archaeology and History of Christianity in England, 400–1200: Papers in Honour of Martin Biddle and Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle, Oxford, British Archaeological Report 505.

- Gosden, C and Marshall, Y 1999, ‘The cultural biography of objects’, World Archaeology 31, 169–78.

- Gretzinger, J, Sayer, D, Justeau, P et al 2022, ‘The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool’, Nature 610:7930, 112–9.

- Halsall, G 1995, Early Medieval Cemeteries: An Introduction to Burial Archaeology in the Post-Roman West, Skelmorlie: Cruithne Press.

- Halsall, G 2002, Settlement and Social Organization: The Merovingian Region of Metz, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Härke, H 1989, ‘Early Saxon weapon burials: frequencies, distributions and weapon combinations’, in S C Hawkes (ed), Weapons and Warfare in Anglo-Saxon England, Oxford: Oxbow, 49–61.

- Härke, H 1997, ‘The nature of burial data’, in C K Jensen and K Hoilund Nielsen (eds), Burial and Society. The Chronological and Social Analysis of Archaeological Burial Data, Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 19–28.

- Härke, H 2000, ‘The circulation of weapons in Anglo-Saxon society,’ in Rituals of Power: From Antiquity to the Early Medieval Ages, Leiden: Brill, 8, 377–99.

- Hawkes, S C and Page, R I 1967, ‘Swords and runes in South-East England’, Antiq J, 48, 1–26.

- Hills, C and Lucy, S 2013, Spong Hill, Cambridge: McDonald Institute.

- Holtorf, C 2008, ‘The life history approach to monuments: an obituary?’, in J Goldhahn (ed), Kalmar Studies in Archaeology 4, 411–27.

- Klevnäs, A M 2013, Whodunnit?: Grave Robbery in Anglo-Saxon England and the Merovingian Kingdoms, Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Klevnäs, A M 2015, ‘Give and take: grave goods and grave robbery in the Early Middle Ages’, in A Klevnäs and C Hederstierna-Jonson (eds), Owned and Be Owned; Archaeological Approaches to the Concept of Possession, Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 62, 157–88.

- Koch, U 2001, Das Alamannisch-Fränkische Gräberfeld bei Pleidelsheim, Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Fruhgeschichte in Baden-Wurttemberg 60, Stuttgart: Kommissionsverlag, K Theiss.

- Komter, A 2001, ‘Heirlooms, Nikes and bribes: Towards a sociology of things’, Sociology, 35, 59–75.

- Kopytoff, I 1986, ‘The cultural biography of things: Commoditization as process’, in Appadurai, 64–91.

- Kristoffersen, S 1999, ‘Swords and brooches. Constructing social identity’, in M Rundkvist (ed), Grave Matters. Eight Studies of First Millennium ad Burials in Crimea, England and Southern Scandinavia, British Archaeological Report, International Series 781, 94–114.

- Lillios, K 1999, ‘Objects of memory: The ethnography and archaeology of heirlooms’, Journal of Archaeology, Method and Theory 6, 235–62.

- Lucy, S 2000, The Anglo-Saxon Way of Death: Burial Rites in Early, England, Stroud: Sutton.

- Lucy, S J 1997, ‘Housewives, warriors and slaves? Sex and gender in Anglo-Saxon burials’, in J Moore and E Scott (eds), Invisible People and Processes: Writing Gender and Childhood into European Archaeology, London: Leicester University Press, 150–68.

- Mauss, M 1954, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Society, London: Cohen and West.

- Menghin, W 1983, ‘Das Schwert im frühen Mittelalter’, Chronologisch-typologische Untersuchungen zu Langschwertern aus germanischen Gräbern des, 5, 7.

- Mortimer, P and Bunker, M 2019, The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England from the 5th to 7th Century, Little Downham: Anglo-Saxon Books.

- Noterman, A 2021, Approche archéologique des réouvertures de sépultures merovingiennes dans le Nord de la France (VI-VIII siècle), Oxford, British Archaeological Report 3065.

- O'Connor, S, Solazzo, C and Collins, M 2015, ‘Advances in identifying archaeological traces of horn and other keratinous hard tissues’, Stud Conserv 60:6, 393–417.

- Oliver, L 2002, The Beginnings of English Law, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Parfitt, K and Anderson, T 2012, Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, Dover: Excavations, Vol 6, Canterbury: Canterbury Archaeology Trust.

- Reilly, S. A 2004, Our Legal Heritage: The First Thousand Years: 600–1600, 5th edn, Project Gutenberg.

- Riddler, I and Trevarthen, M 2006, The Prehistoric, Roman and Anglo-Saxon Funerary Landscape at Saltwood Tunnel, Kent, CTRL integrated site report series, in ADS 2006.

- Sayer, D 2010, ‘Death and the family’, Journal of Social Archaeology 10, 59–91.

- Sayer, D 2020, Early Anglo-Saxon Cemeteries: Kinship, Community and Identity, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Sayer, D and Williams, H 2009, ‘Hall of mirrors’: death and identity in medieval archaeology’, in D Sayer and H Williams (eds), Mortuary Practices and Social Identities in the Middle Ages, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1–22.

- Sayer, D, Sebo, E and Hughes, K 2019, ‘A double-edged sword: Swords, bodies and personhood in early medieval archaeology and literature’, European Journal Archaeology 22, 1–25.

- Scull, C 1999, ‘Social archaeology and Anglo-Saxon Kingdom origins’, Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 10, 17–24.

- Scull, C 2001, ‘Local and regional identities and processes of state formation in fifth- to seventh- century England: some archaeological problems’, in B Arrhenius (ed), Kingdoms and Regionality: Transactions from the 49th Sachsensymposium in Uppsala, Stockholm: Archaeological Research Laboratory, 121–6.

- Semple, S 2008, ‘Polities and princes ad 400–800: New perspectives on the funerary landscape of the south Saxon Kingdom’, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 27, 407–29.

- Skeates, R 1995, ‘Animate objects: a biography of prehistoric ‘axe-amulets’ in the central Mediterranean region’, Proc Prehist Soc 61, 279–301.

- Steuer, H 1987, ‘Helm und Ringschwert: Prunkbewaffnung und Rangabzeichen germanischer Krieger—eine Ubersicht’, Studien zur Sachsenforschung 6, 189–236.

- Stoodley, N 1999, The Spindle and the Spear: A Critical Enquiry into the Construction and Meaning of Gender in the Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Rite, Oxford, British Archaeological Report 288.

- Swanton, M J 1974, A Corpus of Pagan Anglo-Saxon Spear-Types, (Vol. 6). Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Weiner, A B 1992, Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While Giving, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Welch, M 2007, ‘Anglo-Saxon Kent’, in J Williams (ed), The Archaeology of Kent, Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 187–250.

- Welch, M 2011, ‘The Mid Saxon ‘Final Phase’’, in H Hamerow, D Hinton and S Crawford (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 266–87.

- Wessman, A 2007, ‘Reclaiming the past: Using old artefacts as a means of remembering’, in A Šnē and A Vasks (eds), Memory, Society, and Material Culture: Papers from the Third Theoretical Seminar of the Baltic Archaeologists (BASE) Held at the University of Latvia, October 5–6, 2007, Interarchaeologia 3, 71–88.

- Whitelock, D 1930, Anglo-Saxon Wills, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whitley, J 2002, ‘Objects with attitude: Biographical facts and fallacies in the study of late Bronze Age and early Iron Age warrior graves’, Cambridge Archaeology Journal, 12, 217–32.

- Williams, H 2005, ‘Keeping the dead at arm’s length’, Journal Social Archaeology 5, 253–75.

- Williams, H 2006, Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.