Abstract

This article examines the practice of the Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS) regarding the consent regime for marine scientific research (MSR), identifying trends in the interpretation and application of international law, and implementation gaps. The state practice analyzed is derived from domestic laws, regulations, and policy instruments, and from responses to questionnaires by state officials responsible for interpreting and applying the MSR consent regime. It concludes that the framework is fit for purpose and that states share a common interest of furthering marine research, while proposing recommendations for future-proofing the consent regime and advancing the scientific and technological capacity of the Caribbean SIDS.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

The enhancement of the scientific and technological capabilities of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) is fundamental to addressing vulnerabilities arising from their special circumstances.Footnote1 This theme has gained prominence in recent policy and legal developments in ocean affairs, such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14,Footnote2 the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (Ocean Decade),Footnote3 and the 2023 Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement).Footnote4 Despite the absence of dedicated rules for SIDS within the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS or Convention),Footnote5 it is suggested that their special circumstances were considered during the negotiation of the Convention, opening new avenues for exploration regarding its normative potential.Footnote6 In this context, this article contributes to the body of literature scrutinizing the fitness for purpose of UNCLOS in addressing contemporary concerns, by investigating the state practice of Caribbean SIDS concerning the consent regime for marine scientific research (MSR) under UNCLOS. The analysis highlights trends, good practices, and implementation gaps, and proposes recommendations.

Like other SIDS, the Caribbean islands and low-lying states share a strong sociocultural and economic connection with the ocean.Footnote7 Engaging in and reaping the benefits of MSR and accessing marine technology are fundamental to effectively manage the Sargassum influx,Footnote8 manage marine waste,Footnote9 improve blue economic sectors,Footnote10 fulfill international obligations,Footnote11 and ultimately, ensure the continued existence of the Caribbean SIDS.Footnote12 Despite the considerable time that has elapsed since the adoption of the Convention, the involvement of these states in MSR projects continues to be impeded by inadequate infrastructure, insufficient and inconsistent funding, and limited human resources.Footnote13

Often considered the “Constitution for the Oceans,” UNCLOS provides the framework governing activities in and uses of the ocean.Footnote14 Its preamble underscores the objective of promoting equitable and efficient utilization and conservation of marine resources, along with fostering MSR and protecting the marine environment. The Resolution on Development of National Marine Science, Technology and Ocean Service Infrastructures, appended to the Final Act of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, highlights that the MSR regime under UNCLOS not only fosters the conduct of MSR activities but also embodies an equity dimension, urging consideration of the special needs and interests of developing countries and the sharing of marine scientific and technological advancements to bridge the gap between developed and developing states.Footnote15

Part XIII of UNCLOS encompasses the majority of provisions governing MSR, comprising 27 articles across six sections. Through a number of negotiated compromises, Part XIII endeavors to strike a balance between the freedom of all states to conduct research, and the sovereignty and sovereign rights of coastal states in zones adjacent to their coasts,Footnote16 while concurrently seeking to enhance the scientific and technological capabilities of developing countries.Footnote17 Accordingly, while the principle of freedom to conduct research prevails on the high seas (Articles 87(1)(f) and 257) and in the Area (Article 256), coastal states have a degree of control over MSR conducted in the territorial sea and exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and on the continental shelf—collectively, areas under national jurisdiction (AUNJ).Footnote18 The specific rights and obligations of coastal states in each of these AUNJ are established in the “consent regime” set out in Articles 245, 246, 248, and 249.Footnote19 In addition, Part XIII is intricately linked with Part XIV, governing the development and transfer of marine technology, so the implementation of one part positively influences the other.

The central inquiry of this article is: What is the state practice of Caribbean SIDS regarding the consent regime for MSR under UNCLOS? This question arises from the recognition of an information gap with respect to the interpretation and application of the MSR consent regime in contemporary state practice, particularly regarding SIDS.Footnote20 This gap is significant given the observed imbalance in the influence that the practice of developed states has had in the development of international law.Footnote21 The importance of state practice for elucidating the provisions governing the consent regime for MSR is underscored by Article 297(2), which grants a coastal state the option to abstain from accepting the submission of disputes related to the exercise of a right or discretion under Article 246 or the decision to order the suspension or cessation of an MSR activity to the compulsory dispute settlement mechanisms in Part XV of UNCLOS.Footnote22 Through an examination of Caribbean SIDS’ practices, the article identifies trends, best practices, and implementation gaps, and also emphasizes potential interpretative changes that could enhance the involvement of these states in MSR projects.

This article consists of five sections. The first section outlines the methods employed to gather information on the practice of the Caribbean SIDS. The second section analyzes the Caribbean SIDS’ practice in relation to (i) the definition of MSR, encompassing an assessment of three activities with ambiguous definitions; (ii) the exercise of jurisdiction over MSR; (iii) the obligations to grant consent under normal circumstances and provide relevant information; (iv) the right to withhold consent; (v) the obligations to be adhered to during and after the research; and (vi) the right to suspend or terminate the project. The fourth section discusses the findings and proposes recommendations to both coastal states and states conducting MSR (“researching states”). Finally, the fifth section offers closing remarks, emphasizing the common interest of states in advancing MSR and proposing adjustments in MSR governance to enhance the efficiency of the consent process while enhancing marine scientific knowledge, research capacity, and the share of marine technology transferred to Caribbean SIDS.

Before proceeding, some clarifications are warranted. First, for the purpose of this article, state practice denotes a consistent conduct reflecting the state’s interpretation of UNCLOS, not contingent upon uniformity or a specific time span.Footnote23 Second, the article focuses on the implementation of the consent regime in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, considering that the rights of coastal states in the territorial sea regarding MSR are less contentious.Footnote24 Third, while Part XIII regulates MSR conducted in AUNJ by both states and international organizations, the latter are only mentioned when necessary, as they follow a specific procedure for obtaining consent from the coastal state. Likewise, the analysis only tangentially refers to the framework governing the installation and use of equipment for MSR.

Materials and Methods

The state practice analyzed for this study was obtained from national laws and policy instruments, questionnaires, and secondary sources. Notably, these are within the acceptable means to ascertain the subsequent practice of states outlined by the International Law Commission (ILC).Footnote25

The starting point for the selection of states for analysis was the classification of SIDS by the United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries, and Small Island Developing States. This list was cross-referenced with United Nations membership and ratification of UNCLOS. Certain countries were excluded from the analysis due to difficulties in contacting relevant authorities and accessing legislative information. As a result, the analysis focuses on the practice of Antigua and Barbuda, (the) Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Christopher and Nevis (St. Kitts and Nevis), Saint Lucia (St. Lucia), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG), and Trinidad and Tobago.

Legislative Database

The legal analysis relies on a database developed for this study encompassing domestic and regional laws, policies, guidelines, and template forms relevant to the application of the consent regime for MSR within the 14 states under consideration. These documents were sourced from the official websites of the respective governments and the following platforms: Ecolex, Global Lex, FAO Lex, the United Nations Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (DOALOS), U.S. Department of State, Commonwealth Caribbean Law Research Guide, Digital Library of the Caribbean, and Lexadin. The search utilized the following keywords: marine scientific research, scientific research, scientific permit, research permit, marine collection permit, bioprospecting, genetic resources, hydrographic survey, ocean observation, and bathymetric survey. This systematic approach yielded a total of 53 laws, 10 policy instruments, and 10 guidelines, which are set out in .

Table 1. Legislation database.

Questionnaires

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (IOC-UNESCO) distributed a questionnaire (hereinafter Q3) to all its member states between 2002 and 2008 to collect information on the implementation of Part XIII of UNCLOS.Footnote26 Among the Caribbean SIDS included in this study, the Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Saint Lucia responded to Q3.

Using Q3 as a template, a second questionnaire was developed for this study (hereinafter QA) covering the period from 2009 to 2021. While replicating many questions from Q3, QA introduces additional inquiries to elucidate the interpretation of activities with uncertain classification and to gather qualitative insights on the implementation of the consent regime in each national jurisdiction.

Initially, QA was planned for in-person application during international events with the participation of Caribbean SIDS representatives. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and resulting social distancing measures, data collection had to be adapted to a virtual format. Acknowledging concerns in the literature about low response rates to online questionnaires, trusted intermediaries played a crucial role in facilitating access to government officials responsible for implementing the consent regime in Caribbean SIDS.Footnote27 The trusted intermediates included not only individuals, but also international, subregional, and regional organizations and knowledge groups. Such an approach resulted in a network of 70 stakeholders from the institutions outlined in .Footnote28 In 2022, with the easing of restrictions on international gatherings, in-person attendance at a regional workshop in Dominica organized by the World Maritime University (WMU) and the United Nations Ocean Conference in Lisbon provided an opportunity to gather the final responses to QA.

Table 2. Organizations and groups contacted.

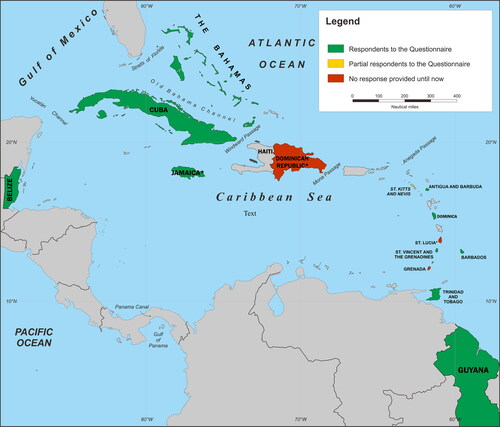

As a result of such efforts, QA garnered completed responses from the following 10 countries: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Dominica, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago. Additionally, Saint Kitts and Nevis provided a partial response to QA. illustrates the Caribbean SIDS participating in this study and the level of responses to QA.

The analysis also relies on responses to Q3 from the Dominican Republic and Saint Lucia. Therefore, the only Caribbean SIDS from which the study was unable to collect response to any of the questionnaires was Grenada. To supplement the primary data, secondary sources such as academic literature and the websites of the U.S. Department of State and the University of Hamburg were consulted.Footnote29

How Are the Caribbean SIDS Interpreting and Applying the Consent Regime for MSR under UNCLOS?

The analysis of the state practice of the Caribbean SIDS on the consent regime for MSR begins by checking which activities have been interpreted as MSR. It proceeds by examining the exercise of jurisdiction over MSR. Finally, it investigates the interpretation and application of the rights and obligations before, during, and after the research cruise.

What Activities Constitute MSR?

UNCLOS provides a precise framework for categorizing activities as MSR compared to its precursor, the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf.Footnote30 Under the UNCLOS framework, MSR projects must have the primary aim of increasing the knowledge about the marine environment, be conducted for peaceful purposes, employ appropriate means and methods, refrain from interfering with other uses of the sea, and comply with relevant regulations, including for the protection and preservation of the marine environment (Article 240).Footnote31 Furthermore, UNCLOS makes clear that MSR activities do not provide a legal basis for claiming any part of the marine environment or its resources (Article 241). Despite this guidance, the classification of certain activities remains disputed, with the main divergence relating to the extent to which activities that are claimed to be MSR may have “direct significance for the exploration and exploitation of resources” and the distinction between MSR and prospecting and exploration. An additional challenge to the classification of activities arises from technological advancements enabling the collection of data for various purposes.Footnote32 Consequently, coastal states have significant flexibility in determining which foreign activities constitute MSR and are subject to prior consent.Footnote33

The analysis reveals that Caribbean SIDS typically apply Part XIII of UNCLOS to all activities involving the in situ collection of samples and data in AUNJ with the aim of contributing to the expansion of knowledge about the ocean space. For instance, a respondent to QA stated that “in practice [MSR] has been interpreted as any research, in any discipline being undertaken within the marine waters of [the state].” Furthermore, it seems that Caribbean SIDS do not differentiate between MSR, scientific research, and research. For example, the concept of “scientific research” and “research” in the Bahamian laws overlaps with the understanding of MSR. Similarly, Belize defines “research” or “scientific research” as synonyms for MSR, while St. Kitts and Nevis only refers to “research,” and Trinidadian law refers to “fisheries scientific research.” Other domestic instruments lack any specific definitions, and appear to interchangeably use these terms when implementing Part XIII. This assumption was confirmed by QA responses. It is noteworthy that Dominica and Guyana are exceptions, because their laws expressly refer to MSR as research activities studying the marine environment.

Examining the intricacies related to the definition of MSR, the study investigates the interpretation of three activities with disputed classification, namely, bathymetric surveys, ocean observation, and scientific research involving access to marine genetic resources (MGRs).Footnote34 Bathymetric surveys are a kind of hydrographic survey primarily utilized for safety of navigation. Based on the language of Articles 19(2)(j) and 40, some scholars consider that they fall outside the purview of Part XIII.Footnote35 As a consequence, bathymetric surveys unrelated to the exploration and exploitation of living resources in the EEZ or on the continental shelf would be considered to fall within the freedom of navigation.Footnote36 In contrast, an alternative interpretation includes these surveys within the ambit of Part XIII, as the data collected can serve both management and scientific studies, as well as contribute to the exploitation of marine resources.Footnote37 This interpretation aligns with the stance of countries like China and India, which mandate prior notification for bathymetric surveys.Footnote38 Interestingly, the majority of Caribbean SIDS seem not to adhere to the Chinese and Indian interpretation, with only approximately one-third of respondents indicating a requirement for prior consent to such activities (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica).

Ocean observation is an integral component of operational oceanography,Footnote39 playing a pivotal role in the analysis and prediction of climate patterns and ocean conditions. During the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, the Chairman of the Third Committee asserted that Part XIII would not impede the coverage of meteorological data.Footnote40 Based on this statement, some states interpret operational oceanography as being excluded from the purview of Part XIII.Footnote41 However, negotiations on guidelines for Argo Floats revealed divergent views regarding this interpretation, highlighting the unsettled nature of such classification.Footnote42 The practice of the Caribbean SIDS reinforces the divergence of perspectives on this issue, as half of the respondents to this question consider Part XIII applicable to ocean observation (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Jamaica, and SVG).

In recent decades, the research into and utilization of MGRs has garnered increasing attention, driven by the economic benefits involved, the disparate capacities of states to engage in such activities, and potential regulatory gaps. In AUNJ, the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)Footnote43 and the 2010 Nagoya ProtocolFootnote44 govern the access, utilization, and benefit sharing of MGRs. Despite provisions aimed at harmonizing the relationship between UNCLOS and the CBD, there are divergent views on whether the in situ collection of MGRs in AUNJ falls within the scope of Part XIII or exclusively within the CBD and Nagoya Protocol framework. In effect, both frameworks can be reconciled, with the caveat that UNCLOS provides greater discretion for coastal states to deny access to MGRs, while the CBD requires access on mutually agreed terms.Footnote45 Interestingly, the majority of the respondents (63 percent) encompass research, utilization, and commercialization of MGRs within the definition of MSR (Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Dominica, Guyana, and St. Lucia). However, a few differentiate between bioprospecting and MSR (Bahamas, Dominican Republic, St. Kitts and Nevis, and Trinidad and Tobago).

In summary, the Caribbean SIDS have adopted an “expansive” approach to the interpretation of MSR activities, often using the terms “research,” “scientific research,” and “MSR” interchangeably. Regarding the classification of activities, a prevailing trend requires prior consent in accordance with Part XIII for research involving the collection of MGRs and ocean observation. In a limited number of cases, prior consent is deemed necessary for bathymetric surveys. With these insights, the logical progression involves an examination of how these states have exercised jurisdiction over MSR.

Jurisdictional Claims over MSR

Part XIII of UNCLOS establishes the rights and obligations of coastal states in relation to researching states, aiming to address the divisions between developing and developed states that were prominent during the negotiation of UNCLOS.Footnote46 In the territorial sea and archipelagic waters, coastal states exercise sovereignty and possess exclusive rights to regulate, authorize, and conduct MSR activities. They have the authority to require explicit consent for any research activity, even during innocent or transit passage (Articles 19 and 40), and can impose conditions on such activities (Articles 49 and 245).Footnote47 In contrast, in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, coastal states enjoy jurisdiction over MSR activities, but only to the extent specified in the relevant provisions of UNCLOS (Articles 56(1), 77(1), and 246).Footnote48 In these areas, while other states are required to seek the coastal state’s consent to conduct MSR, the coastal state’s right to refuse consent is limited, and consent can be deemed to be implied in certain cases. On the continental shelf extending beyond 200 nautical miles the coastal state’s right to withhold consent is further restricted, as will be further explained.Footnote49

To some extent, all Caribbean SIDS assert their rights to regulate, authorize, and conduct MSR activities in AUNJ. In more nuanced terms, their practices align with the trends identified by Wegelein in the context of global practices.Footnote50 The first trend corresponds to states that replicate the provisions of UNCLOS in their domestic laws without further elaboration of the rights and duties involved (Cuba, Belize, Dominica, and the Dominican Republic). The second trend involves states that, in domesticating UNCLOS, diverge from Part XIII in the terminology or substance of powers. This is the case for St. Kitts and Nevis and St. Lucia, which assert “exclusive rights” for authorizing, regulating, and conducting MSR in the EEZ and on the continental shelf. In a similar vein, Grenada establishes “exclusive jurisdiction” to regulate, authorize, and control MSR in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, while Antigua and Barbuda claim “jurisdiction” in the EEZ and “exclusive jurisdiction” on the continental shelf. Furthermore, Guyana claims sovereign rights over MSR in the territorial sea. The third trend includes states whose legislation is silent regarding jurisdiction over MSR in a maritime zone. For example, SVG asserts “control” over MSR only in the EEZ, and Barbados claims “all rights and jurisdiction” regarding MSR in the EEZ. Similarly, the legislation of Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago affirms jurisdiction in the EEZ without any reference to MSR on the continental shelf, while the legislation of the Bahamas does not explicitly assert jurisdiction over MSR.

Overall, the assertion of powers by Caribbean SIDS regarding MSR demonstrates a lack of conformity with Part XIII, also noted in previous studies.Footnote51 The following subsections examine the extent to which this lack of conformity has impacted the exercise of the related rights and obligations by coastal and researching states.

The Obligation to Grant Consent in Normal Circumstances

As previously articulated, the consent regime establishes a framework of rights and obligations between coastal and researching states. In the territorial sea, foreign MSR requires express consent from the coastal state, which holds the right to impose any condition in exchange (Article 245). Differently, in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, foreign MSR necessitates a prior request for coastal state consent, which must be granted under “normal circumstances” for projects enhancing knowledge of the marine environment for humankind’s benefit (Article 246(4)), and may be considered implied if there is no response from the coastal state within four months of the clearance request (Article 252). In this respect, coastal states must establish rules and procedures for MSR requests in the EEZ and on the continental shelf to prevent unreasonable delays or denials of clearance (Article 246(3)). Conversely, researching states must provide a comprehensive description of the project at least six months in advance, including its nature, objectives, methods, description of the research vessel and equipment used, geographical area, dates of appearance and departure, sponsoring institution information, and the extent of the coastal state’s participation (Article 248).Footnote52 If the information provided is deemed unsatisfactory, coastal states may request supplementary information (Article 252(c)).

Assessing the practice of the Caribbean SIDS may assist in the interpretation and implementation of the details of such provisions, especially concerning the EEZ and continental shelf. For instance, it can assist to identify how the expression “normal circumstances” has been interpreted, as currently, the only situations deemed “abnormal” for the purpose of Article 246 pertain to proposals to conduct MSR in areas subject to jurisdictional disputes or facing an imminent possibility of armed conflict.Footnote53 As assessment of practice can also provide information about the adoption of dedicated rules and guidance to avoid delayed consent. Furthermore, it can clarify whether the list of information required before conducting MSR and the obligations that apply after the consent for MSR is granted should be considered open for additions since, in contrast with views supporting the exhaustive character of this list, there have been instances where additional requirements have been accepted.Footnote54

This study did not identify dedicated laws regulating MSR in any Caribbean SIDS. Usually, the requirement for prior consent to MSR is incorporated within fisheries regulations, underscoring the significance of the fishing sector for these countries (e.g., Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, SVG, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, Trinidad and Tobago).Footnote55 In some cases, the scope of the legislation in which MSR is regulated extends beyond fisheries, encompassing the broader regulation of marine biodiversity and living resources as well (e.g., Antigua and Barbuda and St. Lucia). In this respect, there is an emerging trend of integrating scientific research regulations into biodiversity laws, accompanied by stipulations on benefit-sharing (e.g., Belize and Bahamas). Notably, there is a similarity in the provisions regulating MSR in the fisheries acts of the OECS member states, such as Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. This highlights the significance of regional organizations in coordinating a common regulatory and policy approach to MSR, in accordance with Article 123(c).

The practice of Caribbean SIDS regarding the granting of consent for MSR can be categorized into three approaches. The first category includes countries that have implemented guidelines, procedures, and consent templates that address the information required under Article 248 and add new requirements (Bahamas, Belize, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic). Belize has a template form and guidelines, delineating the steps required to obtain a permit in accordance with UNCLOS and related treaties such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).Footnote56 In a positive development since Q3, Jamaica has adopted guidelines, procedures, and a template form for seeking consent under Part XIII, with specific requirements for projects falling under Article 246(5). The Dominican Republic has established rules governing MSR in marine protected areas (MPAs) and introduced a consent form for fisheries research. The Bahamas, under the Biological Resources and Traditional Knowledge Act, has developed a purposeful online application guide consolidating criteria for obtaining research permits under various international instruments, including UNCLOS, CITES, the Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife Protocol,Footnote57 and the Nagoya Protocol. However, certain aspects of the new law have faced criticism nationally and internationally due to the imposition of a substantial nonrefundable annual registration fee for researchers and institutions (in addition to individual permit charges), as well as the lack of consultation with civil society during the adoption process.Footnote58 Scientists have emphasized that such requirements have rendered it impractical to conduct MSR activities in the country, jeopardizing conservation partnerships, especially those involving nongovernmental organizations and international institutes.Footnote59 The matter is under discussion, with the potential for the adoption of a more straightforward procedure for not-for-profit research as a possible breakthrough.

The second category consists of countries that have implemented consent forms, with general information required prior to the research expedition (Antigua and Barbuda, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis). Of particular note, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago are currently in the process of developing guidelines and application forms. The third category encompasses countries where no guidelines, procedures, or templates relating to MSR were identified (Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Grenada, and SVG). Despite being within this group, Barbados has expressed its acceptance of the template forms prepared by DOALOS.

Concerning the introduction of new requisites in the precruise phase, four observations merit consideration. First, the submission of risk assessments or environmental impact assessments (EIAs) in this phase has garnered international support and is found within the practice of some of Caribbean SIDS. Second, there is a prevailing trend of seeking information regarding the use of the research or its implications for traditional and indigenous knowledge, signifying the influence of other legal regimes (e.g., the CBD) within the law of the sea. Third, the practice of requiring payment of administrative fees to process consent requests, widespread among Caribbean SIDS, is supported by scholarship and United Nations documents,Footnote60 finding no opposition in the literature consulted or in the manuals regulating foreign MSR in the United Kingdom and United States.Footnote61 Fourth, there is general support for requesting the documentation in the precruise phase and the presentation of preliminary and final reports in a language readable by the coastal state.Footnote62 summarizes the specific requirements for consent applied by each state according to its respective laws and regulations.

Table 3. Caribbean SIDS additional requirements to grant consent for foreign MSR projects

Establishing formal channels to handle MSR requests is a significant measure to streamline the process of granting consent and facilitate the monitoring of compliance with pre- and postconsent obligations.Footnote63 The analysis reveals that the Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica have established dedicated departments for MSR (see ), while Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Dominica, Guyana, and SVG have designated channels for processing MSR applications.

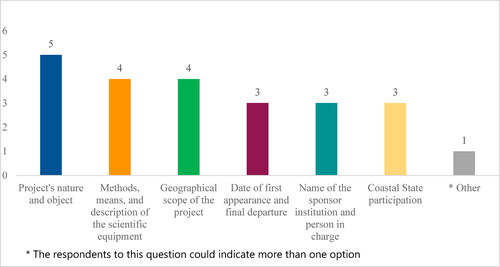

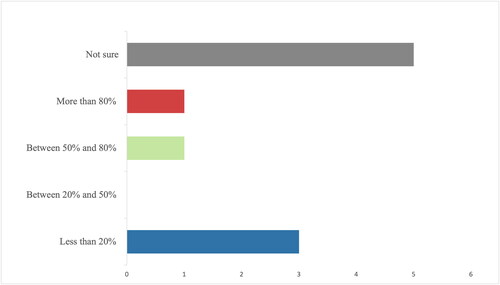

With regard to the practice of processing the consent requests, the responses to QA reveal a shared interest among Caribbean SIDS in promoting and advancing MSR in compliance with UNCLOS. The approval rate for foreign MSR requests is at 96.7 percent, reinforcing the findings of previous studies.Footnote64 Among the respondents to QA, 60 percent reported processing research applications in less than four months (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Guyana, and SVG), and the guidelines from Belize and St. Lucia suggest an approximate processing time of around 20 days. Approximately one-third of QA respondents advised that the information submitted by researching states needs to be supplemented in only 20 percent of the requests (), generally to help the coastal state discern the nature and purpose of the activity (). Furthermore, conducting MSR projects under implied consent remains exceptional, only reported by Belize, Cuba (QA), and the Dominican Republic (Q3). In a statement that seems to summarize the Caribbean SIDS’ approach to the consent regime for MSR, a respondent to QA affirmed that the country avoids unnecessarily restricting MSR; instead, the stakeholders involved rely on direct contacts and ad hoc agreements to achieve a balanced alignment between national interests and the promotion of scientific research.

Figure 2. Number of cases in which supplementary information was required to support MSR request. (Prepared by author.)

In general, more than half of the Caribbean SIDS have implemented guidelines and procedures to prevent unjustified denial or delay of consent. Some have adopted comprehensive tools to consolidate information on research requests based on various legal frameworks. Also, several have established official channels for processing foreign MSR applications. However, none of them have provided further clarification on the interpretation of “normal circumstances” or adopted dedicated legislation to govern MSR. In addition to the requirements listed in Article 248, these countries have sought information regarding the impact of research on traditional knowledge, payment of research fees, and submission of documents in a language understandable to state officials and scientists. The Caribbean SIDS have generally processed the MSR requests in a reasonable time, providing a high rate of approvals.

The Right to Withhold Consent

The coastal state’s authority to deny consent for foreign MSR in AUNJ varies depending on the maritime zone. In the territorial sea, the coastal state possesses broader discretion in refusing consent, while in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, consent may only be denied based on grounds outlined in UNCLOS. These include when the research (i) lacks a peaceful purpose or its primary objective does not involve advancing knowledge for humankind; (ii) unreasonably interferes with the coastal state’s activities within its sovereign rights and jurisdiction; (iii) involves drilling or introducing harmful substances into the marine environment; (iv) includes the construction, operation, or use of artificial islands, installations, and structures; and (v) is of direct significance for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources (Articles 240 and 246(3), (5), and (8)). On the extended continental shelf, the last condition applies only within the areas publicly designated by the coastal state of interest for exploration and exploitation in a reasonable period of time. Additional grounds for withholding consent may apply (vi) in abnormal circumstances; (vii) where the information about the project’s nature and objectives submitted during the precruise stage is deemed inaccurate; and (viii) if the researching state or relevant international organizations have pending obligations from previous projects (Article 246(3)(5)). In such instances, rather than outright denying permission, coastal states may choose to impose additional requirements on researching states, such as restrictions on the public dissemination of results from research with economic significance (Article 249(2)).Footnote65

Despite the limited legal grounds for denying consent, the open language used in these provisions allows for multiple interpretations, prompting claims that the coastal state holds discretion over consent for all types of MSR in AUNJ.Footnote66 In response to this criticism, this examination of the practice of Caribbean SIDS was carried out in order to reveal any common interpretative trends, particularly concerning the term “direct significance” for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. Additionally, the study sought to explore whether the absence of opportunities for coastal state participation in MSR has been utilized as a trade-off for granting consent—a perspective endorsed by Gorina-Ysern, who argues that such participation has evolved into customary international law.Footnote67 Moreover, by examining the implementation of the consent regime by Caribbean SIDS, the study also sought to explore the suggestion that there is an obligation to negotiate consent in cases where the coastal state has discretion to deny it.Footnote68

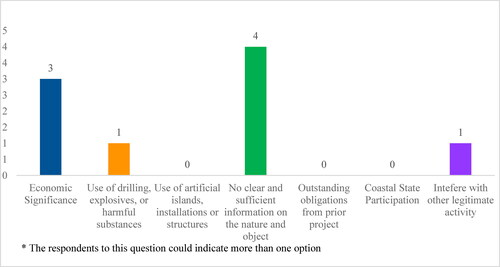

Notwithstanding the high rate of approvals (as already noted), nearly half of the respondents to the QA disclosed instances of consent for foreign MSR being denied. The primary ground for refusal was inadequate information regarding the nature and objective of the project, hindering the assessment of the project’s bona fides. This was followed by cases where the proposed activity would have economic significance for the exploration or exploitation of natural resources, cause harm to the marine environment, or unjustifiably interfere with the sovereign rights and jurisdiction of the coastal state ().

Altogether, the Caribbean SIDS have generally exercised their right to deny consent on the bases provided by UNCLOS. No discernible trend or specific approach could be identified concerning the interpretation of the term “direct significance” for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources, and no evidence suggests that consent requests have been declined due to the absence of opportunities for coastal state participation. Lastly, notwithstanding the earlier affirmation that Caribbean SIDS generally favor the approval of consent requests, sometimes through direct contact and ad hoc agreements, it remains unclear whether engaging in such informal negotiations has been understood as an obligation.

The Obligations During and After the Research Cruise

In the territorial sea, the coastal state may require compliance with any kind of obligation in exchange for granting consent, whereas in the EEZ and on the continental shelf, the postconsent obligations are outlined in Article 249. This provision was significant for the adoption of Part XIII,Footnote69 as it enables coastal states to ensure the bona fides of the research, safeguard security, defense, and national interests, prevent harm to the marine environment, and receive benefits from the research.Footnote70 Accordingly, researching states are required to fulfill several obligations, including (i) ensuring the participation of the coastal state, particularly onboard vessels, crafts, or installations; (ii) providing preliminary reports promptly and submitting final results; (iii) granting access to data and samples collected during the research; and (iv) assisting in the assessment of data, samples, and research findings. Additionally, they must (v) ensure the international availability of research results, unless otherwise agreed; (vi) inform the coastal state of any significant changes in the research program; and (vii) remove scientific installations and equipment, unless otherwise agreed. The prevailing interpretation asserts that this list of obligations is exhaustive, meaning that additional requirements can only be included in cases where the MSR project falls within the exceptions permitting denial.Footnote71 As a consequence of the failure to fulfill these obligations, the coastal state may request the suspension of the research activity or withhold future consent applications from the researching state.

One important criticism of Article 249 revolves around the open language used in its obligations, which can be interpreted as allowing options for opting out from compliance (e.g., “when practicable”), being contingent on a prior request by the coastal state, and hindering the monitoring of compliance (“undertake to provide”).Footnote72 Considering this, the examination of the Caribbean SIDS’ practice sought to identify whether such an open language has allowed researching states to avoid meeting international obligations. It also sought to verify whether the obligation to enable coastal state participation in the research cruise has been interpreted as a customary norm. Furthermore, the analysis aimed to understand how the Caribbean SIDS have monitored compliance, and whether they have interpreted the obligations under Article 249 as constituting an exhaustive or indicative list.

The laws and regulations of almost all the Caribbean SIDS analyzed present an upfront statement of interest in participating in the research. Responses to the QA and Q3 indicate that, with the exception of Antigua and Barbuda and SVG, Caribbean SIDS have actively pursued and, to some extent, derived benefits from capacity-building opportunities for deploying their scientists on vessels, crafts, and installations. Although none of the respondents appear to have denied consent due to the absence of opportunities for participation, the widespread practice of requesting participation, supported by the inclusion of this right in many domestic laws, reinforces views about the customary status of this right.Footnote73 However, the details regarding the extent of this right (e.g., the scope and meaning of the right to participate) remain unresolved. For instance, while involving the coastal state in the planning stage of the research has been praised as a good practice, it lacks support in the general practice of states or historical negotiation records.Footnote74 Furthermore, it is unclear whether the expenses associated with the observer’s transportation are included in the costs borne by the researching state.Footnote75 Similarly, certain requisites associated with the right to participate, such as hiring a specific number of local scientists per foreign scientist or applying for work permits, do not seem to find support in the legal doctrine, in the general practice of states, or in a reasonableness test.

The laws and regulations in many Caribbean SIDS require the sharing of data, information, samples, and reports resulting from the research. It is worth noticing that this requirement is imposed in spite of the soft language used in the framing of the Article 249 obligation to share data (that may be copied) and samples (that may be divided). Responses to the QA reinforced that the majority of the participant states—80 percent—have sought access to the data and samples collected during research projects (Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Cuba, Dominica, Guyana, Jamaica, and SVG). Therefore, the subsequent practice of these states has strengthened the requirement to fulfill such an obligation, notwithstanding its voluntary language.

Part XIII omits the time frame in which preliminary and final reports from the research should be shared with the coastal state, probably because it would vary depending on the research. Drawing from the global practices of states and insights from scientists, it has been proposed that a 30-day period would be a reasonable timeframe for the preliminary report.Footnote76 While the analysis did not reveal a shared interpretation of this issue among Caribbean SIDS, it is noteworthy that Jamaica adheres to the 30-day rule for the preliminary report and additionally mandates the sharing of the final report within 12 months of the completion of the research. None of the instruments refer to the need for negotiating consent or prior agreement for publishing results of resource-related MSR, but Belize reserves the right to publish information derived from research in its AUNJ within two years of completion.

On the other hand, just 54 percent of the QA respondents have requested assistance in assessing the collected data and samples (Barbados, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Guyana, St. Kitts and Nevis, and St. Lucia) and only a few of the regulatory instruments analyzed put forward this requirement. Hence, it remains unclear whether the Caribbean SIDS have been able to store and process the data and information received, as well as whether such material corresponds to the emergent needs of these countries.

Another interesting finding of the analysis is the inclusion of novel obligations in addition to the list set out in Article 249 (see ). Among the less contested new requirements are the imposition of additional restrictions to perform MSR in locations governed by area-based management tools (ABMTs) and the requirement for submitting risk assessments or EIAs. These requirements reflect a shift in international law from merely balancing the interests of states toward the protection of common goods,Footnote77 based on Articles 206 and 240(c) and (d), state practice, judicial precedents, scholarly opinions, and other treaties governing scientific research.Footnote78 The imposition of a requirement to inform the national coastal guard about the commencement and conclusion of the research is also less controversial because it aligns with Article 248(d).

Moving to more contentious requirements, it has been increasingly common to find laws and consent templates concerning the monetary and nonmonetary benefits arising from the research—particularly if the study involves biodiversity and MGRs—beyond the obligations stated in Article 249 and the cases of coastal state discretion of Article 246(5). Taking the Bahamian guidelines as example, nonmonetary benefits would include access to data and samples, workshops, training, academic and knowledge exchange, shared publications, joint ownership of intellectual property rights, and technology transfer. On the other hand, monetary benefits would include access fees, up-front payments or royalties, joint ventures, and research funding.

The extent of international acceptance of the benefit-sharing approach to the consent regime remains unclear, although this article argues that it is a sound approach since it aligns with the objectives of Part XIII.Footnote79 During the negotiation of UNCLOS, promoting coastal states’ participation, sharing data, samples, information, and reports, and providing support for data and sample assessment were agreed measures to achieve the purpose of Part XIII. With the development of international law, marked by the adoption of subsequent agreements like the CBD, Nagoya Protocol, and BBNJ Agreement, additional avenues to enhance the research capacities of developing countries emerged. Consequently, the practice of Caribbean SIDS is coherent with the developments in sustainability and equity taking place in other legal realms and remains consistent with the purpose of UNCLOS.

Overall, in exchange for granting access to the marine environment of AUNJ to foreign MSR vessels, Caribbean SIDS have been seeking opportunities to share in the knowledge produced and enhance their autonomous MSR capacities. Their practice demonstrates a concerted effort to strengthen the language of obligations under Article 249 by explicitly requesting opportunities to participate in research activities and the sharing of reports, data, and samples generated from foreign research projects. However, the extent to which these measures have effectively served to address knowledge and management gaps in these countries is unclear, as is their potential to trigger sustained positive changes. De lege ferenda practice by Caribbean SIDS includes seeking information on the benefits accrued from research extending beyond the obligations specified in Article 249 for all types of research, the imposition of additional requirements for MSR projects in ABMT, and requests for the submission of risk assessments or EIAs.

The Right to Request Suspension or Cessation

The last aspect under consideration involves the coastal state’s authority to request the suspension or cessation of a foreign MSR project in AUNJ. These mechanisms, along with the right to withhold consent for unfulfilled obligations, serve as enforcement measures within this framework.Footnote80

Suspension is applicable when the activity deviates from the information provided in the preconsent phase under Article 248, or in cases of noncompliance with obligations under Article 249 (Article 253(1)). It is considered a temporary measure, allowing for the continuation of activities once the misconduct is rectified (Article 253(5)). However, if the researching state fails to address the situation that led to the suspension within a reasonable period, the coastal state may request the permanent discontinuance of the activity. Cessation may also be requested if deviations from the information provided under Article 248 amount to a major change in the research project or activity, thus undermining the basis on which consent was granted.Footnote81 For example, this would be the case if the researching state fails to inform the coastal state about the need to construct artificial islands as part of the project.

Responses to QA and Q3 revealed that only 15 percent of the Caribbean SIDS have ever requested the suspension or cessation of an MSR activity. This reinforces their favorable approach toward promoting foreign MSR, but it is important to note that one-third of the respondents were unable to provide a response to this question, casting doubts on the accuracy of this result and on the effectiveness of the databases within these countries regarding foreign MSR requests. The responses also revealed that instances justifying suspension or cessation were primarily triggered by the realization that the activity had exploitative intentions rather than the scientific purpose initially communicated.

Closing this section, the findings thus far have identified trends, best practices, and potential challenges faced by the Caribbean SIDS in the implementation of the consent regime for MSR. Expanding on this analysis, the following section discusses the significance of these findings and presents recommendations for improving the consent regime.

Discussion and Recommendations Arising from the Identified Trends and Gaps

The BBNJ Agreement, Ocean Decade, SDG 14, and other current developments in ocean governance seeking to enhancing the scientific and technological capacities of SIDS are not occurring in isolation; they are intricately tied to and enabled by the existing framework. To date, the interpretation and application of the consent regime for MSR under UNCLOS have attracted little attention from state officials, scientists, and scholars. In order to bring awareness to this issue, this section discusses key insights gleaned from this study and links them to ongoing initiatives, leading to recommendations for streamlining the process of granting consent while bolstering scientific and technological capacities in MSR within the Caribbean region.

One of the main conclusions of the study is that the practice of the Caribbean SIDS is in accordance with their duty under Article 239 of UNCLOS to promote and facilitate MSR within their AUNJ. In spite of the expansive interpretation of activities requiring prior consent, the findings concerning high rates of timely consent approval, low rates of denial, and reduced instances of research suspension or cessation suggest compliance with the obligation to grant consent under normal circumstances. Additionally, the use of direct communications and ad hoc agreements to address legislative gaps or conflicts during the consent process reflects a generally positive approach to research, even though an obligation to negotiate consent is not clearly evident. The analysis also identifies that while there is a general practice among the Caribbean SIDS of establishing rules and procedures to prevent undue delays or denials in the consent process, a few of them still handle consent requests on an ad hoc basis, and there are instances of failure to register information regarding foreign MSR requests. Therefore, establishing formal channels to handle foreign MSR requests is recommended as a good practice to improve data storage on the consent regime, streamline this process, and facilitate the monitoring of compliance.Footnote82

Curiously, while their laws and guidelines on the specific question of exercising jurisdiction over MSR—such as fisheries acts and consent templates—are generally aligned with UNCLOS, almost all the domestic laws by which the Caribbean SIDS establish and assert jurisdiction over their maritime zones—such as maritime zones acts—do not follow the language used in UNCLOS.Footnote83 Adjusting their maritime zone laws to clarify the substance of powers over MSR under UNCLOS and elaborate on the rights and obligations related to consent would provide greater legal certainty both to the coastal state officials involved in the consent and researching states. It would also likely have a ripple effect throughout the consent process. To improve the consent procedure, the Caribbean SIDS should consider disseminating their laws, guidelines, and templates related to MSR through platforms such as the DOALOS legislative database, regional organizations, or national websites.

The preceding section suggests that researching states have generally fulfilled the obligations under Articles 248 and 249. Nonetheless, the instances where supplementary information was required or consent was denied due to a lack of sufficient basis for assessing the nature and objectives of the research emphasize the need for researching states and principal investigators to enhance efforts in providing a detailed account of the research to support the coastal state’s decision. In effect, establishing a cooperative approach between researching and coastal states is essential to streamline the consent process by fostering trustFootnote84 and avoiding practices considered “colonial science.”Footnote85 Good cooperative practices in international MSR include promoting the meaningful participation of scientists from the coastal state in the project from its early stages, considering national and regional knowledge gaps and socioeconomic aspects during the project planning, monitoring compliance with postconsent obligations, and maintaining a list of noncompliant research institutes.

The preceding analysis also highlights the dynamism of Articles 248 and 249, influenced by developments in other areas of international law and technological advances. The development of additions to the obligations established in these Articles aligns with the right of all states to promote MSR under Article 238 and with the concept of UNCLOS as a living instrument. Consequently, when seeking consent, researching states must be aware that domestic regulations may impose additional requirements to those listed in Article 248. For example, it is increasingly common and accepted to inquire about how the research will impact on and use traditional knowledge, request a risk assessment or an EIA, impose stringent measures for ecologically significant areas, require documentation in a language readable by the coastal state, and request payment of fees based on a reasonableness test (see ). Once given consent, researching states must promote the coastal state’s participation—an obligation that may have acquired customary status—and share reports, information, data, and samples—a requirement commonly found in instruments of the Caribbean SIDS. Expanding on the list of capacity-building opportunities in Article 249, there is a growing trend to inquire about the benefits that the MSR project will bring to the country (see ), and how opportunities for increased cooperation will be created, including in contexts where consent is discretionary and trade-offs may therefore be able to be negotiated.

Regional organizations are well positioned to serve as platforms for adopting necessary regulations, storing and sharing scientific data, and establishing a community of practice.Footnote86 For instance, the OECS, as demonstrated by the analysis, holds significant importance in establishing fisheries laws within its member states. Furthermore, it has taken measures related to MSR, exemplified by initiatives like the 2016 OECS Code of Conduct for Marine Research,Footnote87 2016 OECS Marine Research Strategy,Footnote88 and 2016 Developing OECS Ocean Data Standards and Best Practices,Footnote89 although efforts toward the consent regime are yet to be initiated. In the broader Caribbean region, the Regional Seas Programs also play a crucial role in promoting the exchange of practices pertaining to MSR, in compliance with Article 123 of UNCLOS.Footnote90

summarizes the recommendations for the Caribbean SIDS and researching states.

Table 4. Recommendations in a nutshell

Concluding Remarks

Initiatives like SDG 14, the Ocean Decade, and the BBNJ Agreement underscore the necessity of promoting capacity building, transferring marine technology, and ensuring equity within ocean governance to address vulnerabilities arising from the special circumstances of SIDS. As elucidated in this article, it is crucial to recognize that these initiatives are grounded in the framework laid by UNCLOS, which identifies the enhancement of scientific and technological capacities in developing countries as one of its objectives and has instituted tools, such as the consent regime, to accomplish this objective.

The analysis of the state practice of the Caribbean SIDS discloses their positive inclination to promote and facilitate the development of foreign MSR in their AUNJ. Moreover, in accordance with the dynamic nature of UNCLOS, these countries have adjusted the consent regime to reflect advancements in biodiversity and environmental law—such as ABMT, EIA, and considerations pertaining to the impact of Western science on traditional knowledge—and to incorporate a benefit-sharing perspective into the postconsent obligations. Nevertheless, the Caribbean SIDS have not fully realized their right to conduct MSR.

As described in this article, there is significant potential to streamline the consent process within Caribbean SIDS, concurrently amplifying their engagement in proposed foreign MSR projects and ultimately advancing their autonomous scientific capabilities. The recommendations articulated herein act as a catalyst for this transformative process, underscoring that the essential element for change rests in cultivating a collaborative perspective between researching states and the Caribbean SIDS.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the peer reviewers, whose constructive feedback significantly enhanced the quality of the article. Special gratitude is extended to Dr. Montserrat Gorina-Ysern and Dr. Harriet Harden-Davies for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article. Acknowledgments are also due to Professor Ronan Long and Professor Zhen Sun for supervising the research, Dr. Luisa Hedler for her assistance in English editing and proofreading, as well as to Professor Clive Schofield and Dr. Andi Arsana for their contributions to producing the map used for this study. The author extends thanks to the respondents of QA for generously contributing their time and information. Gratitude is further extended to the organizations and individuals whose cooperation facilitated access to authorities in the Caribbean SIDS.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The special circumstances of SIDS include “small populations and geographies, remoteness, and acute exposure to external shocks”: Alliance of Small Islands States (AOSIS), Submission of Proposals Related to the Further Revised Draft Text of an Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (as reflected in A/CONF.232/2022/5), at: https://www.un.org/bbnj/sites/www.un.org.bbnj/files/bbnj_submissions_template_igc_5_article_5_aosis_0.docx (accessed 30 September 2023).

2 UNGA Resolution A/RES/70/1, Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed 30 September 2023).

3 UNGA Resolution A/RES/72/73, Oceans and the Law of the Sea, 5 December 2017, at: https://undocs.org/en/a/res/72/73 (accessed 11 March 2024).

4 Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction, adopted 19 June 2023, not yet in force, C.N.203.2023.TREATIES-XXI.10.

5 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, adopted 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994, 1833 UNTS 397.

6 Luciana Fernandes Coelho, “Marine Scientific Research and Small Island Developing States in the Twenty-First Century: Appraising the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (2022) 37 International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 493, 507–511.

7 David Read Barker, “Biodiversity Conservation in the Wider Caribbean Region” (2002) 11 Review of European Community & International Environmental Law 74, 75; CARSEA 2007, “Caribbean Sea Ecosystem Assessment (CARSEA): A Sub-Global Component of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA)” (2007) Caribbean Marine Studies, Special Edition; Winston Anderson, The Law of the Sea in the Caribbean (Brill Nijhoff, 2020), 53–57; Harriet Harden-Davies, Diva Amon, Tyler-Rae Chung et al., Science and Knowledge to Support Small Island States Conserve and Sustainably Use Marine Biodiversity beyond National Jurisdiction (University of Wollongong, 2022), 6–9, at: https://www.aosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/SIDS-Marine-Science-Report-Full-Feb-2022.pdf (accessed 30 November 2022).

8 Hazel A. Oxenford, Shelly-Ann Cox, Brigitta I. van Tussenbroek et al., “Challenges of Turning the Sargassum Crisis into Gold: Current Constraints and Implications for the Caribbean” (2021) 1 Phycology 27; Daniel Robledo, Erika Vázquez-Delfín, Yolanda Freile-Pelegrin et al., “Challenges and Opportunities in Relation to Sargassum Events Along the Caribbean Sea” (2021) 8 Frontiers in Marine Science 699664.

9 Kristal K. Ambrose, Carolynn Box, James Boxall et al., “Spatial Trends and Drivers of Marine Debris Accumulation on Shorelines in South Eleuthera, The Bahamas Using Citizen Science” (2019) 142 Marine Pollution Bulletin 145, 146; La Daana K. Kanhai, Hamish Asmath and Judith F. Gobin, “The Status of Marine Debris/Litter and Plastic Pollution in the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem (CLME): 1980–2020” (2022) 300 Environmental Pollution 118919, 3.

10 Pawan G. Patil, John Virdin, Sylvia Michele Diez et al., Toward a Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean (World Bank, 2016), 48 at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25061 (accessed 30 November 2022).

11 Coelho, note 6, 497.

12 Michelle Mycoo, Morgan Wairiu, Donovan Campbell et al., “Small Islands” in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 2043, 2095–2096.

13 IOC-UNESCO, Global Ocean Science Report 2020—Charting Capacity for Ocean Sustainability (UNESCO Publishing, 2017), 130–150 at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000250428 (accessed 14 December 2022); Lucia Fanning, Robin Mahon, Sanya Compton et al., “Challenges to Implementing Regional Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean Region” (2021) 8 Frontiers in Marine Science 667273, 15-16.

14 Tommy T. B. Koh, “A Constitution for the Oceans,” remarks adapted from statements made by the President on 6 and 11 December 1982 at the final session of the Conference at Montego Bay, reproduced in The Law of the Sea. Official Text of the United Nations on the Law of the Sea with Annexes and Index. Final Act of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (United Nations, 1983), xxxiii–xxxvii, at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/koh_english.pdf (accessed 11 March 2024).

15 “Resolution on the Development of National Marine Science, Technology and Ocean Service Infrastructures,” Draft Final Act of the Third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, UN Doc A/Conf.62/121 (1982) 21 ILM 1245, Annex VI.

16 Lucius Caflisch and Jacques Piccard, “The Legal Regime of Marine Scientific Research and the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea” (1978) 38 zaöRV 848, 897; Myron H. Nordquist, Neal R. Grandy, Shabtai Rosenne et al., United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol IV (Martinus Nijhoff, 1990), 433; Nele Matz-Lück, “Article 238: Right to Conduct Marine Scientific Research” in Alexander Proelss (ed), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: A Commentary (CH Beck/Hart/Nomos, 2017), 1605, 1608.

17 Charlotte Salpin, “The Law of the Sea: A Before and an After Nagoya?” in Elisa Morgera, Matthias Buck and Elsa Tsioumani (eds), The 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing in Perspective: Implications for International Law and Implementation Challenges (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2013), 149, 153, 157; Coelho, note 6, 519–524.

18 Caflisch and Piccard, note 16; Daniel P. O’Connell, The International Law of the Sea: Vol II (Oxford University Press, 1988), chapter 26, 1026–1032; Maria Gavouneli, Functional Jurisdiction in the Law of the Sea (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2007), 64; Robert Jennings and Arthur Watts, “The High Seas, Marine Scientific Research” in Robert Jennings and Arthur Watts (eds), Oppenheim’s International Law: Volume 1 Peace (Oxford University Press, 9th ed, 2008), Part 2, chapter 6, 809, 809-811.

19 P. K. Mukherjee, “The Consent Regime of Oceanic Research in the New Law of the Sea” (1981) 5 Marine Policy 98, 101–105; Elie Jarmache, “Sur quelques difficultés de la recherche scientifique marine” in La mer et son droit. Mélanges offerts a Laurent Lucchini et Jean-Pierre Quéneudec (Pedone, 2003), 303, 305–307; Tullio Treves, “Marine Scientific Research” in Rüdiger Wolfrum (ed), Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Law (Oxford University Press, 2008), [8]–[15], at: http://www.mpepil.com (accessed 30 November 2022).

20 IOC-UNESCO, Elizabeth J. Tirpak, “Results of IOC Questionnaire No 3 on the Practice of States in the Fields of Marine Scientific Research and Transfer of Marine Technology: An Update of the 2003 Analysis by Lt. Cdr. Roland J. Rogers” (2005) IOC/ABE-LOS V/7; IOC-UNESCO, Elizabeth J. Tirpak, “Practices of States in the Fields of Marine Scientific Research and Transfer of Marine Technology: An Update of the 2005 Analysis of Member State Responses to Questionnaire No 3” (2008) IOC/ABE-LOS VIII/8; Alfred H. A. Soons, “The Legal Regime of Marine Scientific Research: Current Issues” in Myron Nordquist, Ronan Long, Tomas Heidar et al. (eds), Law, Science & Ocean Management (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2007), 139, 162.

21 Michael Byers, “Introduction: Power, Obligation, and Customary International Law” (2001) 11(1) Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law 81, 84; Dire Tladi, “State Practice and the Making and (Re)Making of International Law: The Case of the Legal Rules Relating to Marine Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction” (2014) (1) Journal of State Practice and International Law Journal 105, 104–105; B. S. Chimni, “Customary International Law: A Third World Perspective” (2018) 112(1) American Journal of International Law 1, 5.

22 Scholars have suggested that Article 297(2) would not exclude from judicial review disputes involving the obligations to provide consent in “normal circumstances” or to establish rules and procedures ensuring consent will not be delayed or denied unreasonably. See J. Ashley Roach, Excessive Maritime Claims 4th edn (Brill Nijhoff, 2021), 519. Nonetheless, no case law related to the consent regime has been identified.

23 International Law Commission, Report of the International Law Commission, Seventieth Session, Subsequent Agreements and Subsequent Practice in Relation to the Interpretation of Treaties, UN Doc A/73/10 (2018), Conclusion 5.

24 Tim Stephens and Donald R. Rothwell, “Marine Scientific Research” in Donald R. Rothwell, Alex Oude Elferink, Karen Scott et al. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea (Oxford University Press, 2015), 559, 575.

25 International Law Commission, note 23, Conclusion 4 [18].

26 Tirpak, note 20.

27 Jessica Daikeler, Michael Bošnjak and Katja Lozar Manfreda, “Web Versus Other Survey Modes: An Updated and Extended Meta-Analysis Comparing Response Rates” (2020) 8 Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 513.

28 The questionnaire was approved by the World Maritime University (WMU) Ethical Committee. The participants consented to having their responses shared in this article without the disclosure of names or personal data.

29 See Montserrat Gorina-Ysern, An International Regime for Marine Scientific Research (Transnational Publishers, 2003); Roach, note 22.

30 Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 569.

31 Alfred H. A. Soons, Marine Scientific Research and the Law of the Sea (Kluwer Law and Taxation Publishers TMC Asser Instituut, 1982), 5–8, 118–125; Yoshifumi Tanaka, The International Law of the Sea, 3rd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2019), 433–434.

32 Robert Beckman and Tara Davenport, “The EEZ Regime: Reflections after 30 Years,” in Securing the Ocean for the Next Generation (UC Berkeley–Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology Conference, Seoul, Korea, 2012), 29–30; Luciana Fernandes Coelho and Roland Rogers, “The Use of Marine Autonomous Systems in Ocean Observation under the LOSC: Maintaining Access to and Sharing Benefits for Coastal States,” in Tafsir Matin Johansson, Dimitrios Dalaklis, Jonatan Echebarria Fernández et al. (eds), Smart Ports and Robotic Systems: Navigating the Waves of Techno-Regulation and Governance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 111, 113–116.

33 Nordquist, Grandy, Rosenne et al., note 16, 518; O’Connell, note 18, 1029; Jarmache, note 19, 311.

34 Soons, Marine Scientific Research and the Law of the Sea, note 31, 118–125; Beckman and Davenport, note 32, 24–31; Paul Gragl, “Marine Scientific Research” in David J. Attard, Malgosia Fitzmaurice and Norman A. Martínez Gutiérrez (eds), The IMLI Manual on International Maritime Law: Volume I: The Law of the Sea (Oxford University Press, 2014), 396, 404–408. The term “bioprospecting” is avoided in this article, because it implies that commercialization is the main aim of the activities from the outset.

35 Florian H. T. Wegelein, Marine Scientific Research. The Operation Status of Research Vessels and Other Platforms in International Law (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2005), 160; Sookyeon Huh and Kentaro Nishimoto, “Article 246: Marine Scientific Research in the Exclusive Economic Zone and on the Continental Shelf” in Alexander Proelss (ed), United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: A Commentary (Beck/Hart/Nomos, 2017), 1649, 1656–1657; Roach, note 22, 26, 37, 452.

36 Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 570–572; Roach, note 22, 492–493.

37 International Hydrographic Organization, Manual on Hydrography, Publication C-13 (2005, Corrections to February 2011), 4.

38 Sam Bateman, “Hydrographic Surveying in the EEZ: Differences and Overlaps with Marine Scientific Research” (2005) 29 Marine Policy 163, 167; Guifang Xue, “Marine Scientific Research and Hydrographic Survey in the EEZs: Closing up the Legal Loopholes?” (2009) 13 Center for Oceans Law and Policy 209, 221; Erik Franckx, “American and Chinese Views on Navigational Rights of Warships” (2011) 10 Chinese Journal of International Law 187, 197.

39 Fraser Davidson, Alvera-Azcárate Aida, Barth Alexander et al., “Synergies in Operational Oceanography: The Intrinsic Need for Sustained Ocean Observations” (2019) 6 Frontiers in Marine Science 1, 1.

40 Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, 46th Meeting of the Third Committee, Report of the Chairman on the Work of the Committee, UN Doc.A/CONF.62/C.3/SR.46 (1980).

41 Huh and Nishimoto, note 35, 1657; Roach, note 22, 417–418; Beckman and Davenport, note 32, 29–31.

42 Aurora Mateos and Montserrat Gorina-Ysern, “Climate Change and Guidelines for Argo Profiling Float Deployment on the High Seas” (2010) 14 ASIL Insights, at: https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/14/issue/8/climate-change-and-guidelines-argo-profiling-float-deployment-high-seas (accessed 10 June 2023).

43 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted 5 June 1992, entered into force 29 December 1993, 1760 UNTS 79.

44 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity, adopted 29 October 2010, entered into force 12 October 2014, CBD Decision X/1 (2010), Annex I.

45 Joanna Mossop, “Marine Bioprospecting” in Rothwell, Elferink, Scott et al. (eds), note 24, 826, 836–837.

46 Mukherjee, note 19, 98; Ram Prakash Anand, Origin and Development of the Law of the Sea (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1982), 240–241; Joanna Mossop, The Continental Shelf Beyond 200 Nautical Miles: Rights and Responsibilities (Oxford University Press, 2016), 153.

47 Malcolm N. Shaw, International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 556–575; Caflisch and Piccard, note 16, 855–859; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 571.

48 Wegelein, note 35, 199–200; Tanaka, note 31, 153–158.

49 Mossop, note 46, 166.

50 Wegelein, note 35, 276–277; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 579.

51 Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 32–34; Wegelein, note 35, 276.

52 DOALOS, “Marine Scientific Research: A Revised Guide to the Implementation of the Relevant Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (2010), 29, 40, 45, at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/702302?ln=en (accessed 11 March 2024).

53 Ibid, 41.

54 Ibid, 40.

55 Anand, note 46, 199–200; Anderson, note 7, 94–97.

56 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, adopted 3 March 1973, entered into force 1 July 1975, 993 UNTS 243.

57 Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife to the Convention for the Protection and Development of the Marine Environment of the Wider Caribbean Region, adopted 18 January 1990, entered into force 18 June 2000, at: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/27271 (accessed 28 February 2024).

58 Rashad Roller, “AG: Minnis Administration Passed Research Law without Proper Consultation” 2 June 2022, Eyewitness News at: https://ewnews.com/ag-minnis-administration-passed-research-law-without-proper-consultation (accessed 10 June 2023).

59 Candace Fields, “We Need ‘A New Day’ for Science in The Bahamas” 15 November 2021, The Tribune at: http://www.tribune242.com/news/2021/nov/15/we-need-new-day-science-bahamas (accessed 10 June 2023); Neil Hartnell, “Ex-Minister: Civil Servants Hijacked New Research Act” 11 April 2022, The Tribune, at: http://www.tribune242.com/news/2022/apr/11/ex-minister-civil-servants-hijacked-new-research-a (accessed 10 June 2023).

60 DOALOS, note 52, 28; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 571; Sookyeon Huh and Kentaro Nishimoto, “Article 255: Measures to Facilitate Marine Scientific Research and Assist Research Vessels” in Proelss (ed), note 35, 1713, 1716.

61 National Oceanography Centre, “Chief Scientist Guidance Notes” (2019), available at: https://www.ukri.org/publications/chief-scientists-on-nerc-research-ships-guidance-and-guidelines (accessed 11 March 2024); US Department of State, “About the Research Application Tracking System,” available at: https://www.state.gov/research-application-tracking-system (accessed 10 June 2023).

62 DOALOS, note 52, 40.

63 Ronán Long, “Regulating Marine Scientific Research in the European Union: It Takes More than Two to Tango” in Myron H. Nordquist, John Norton Moore and Alfred H.A. Soons et al. (eds), The Law of the Sea Convention: US Accession and Globalization (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2012), 428, 479.

64 Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 37–38; DOALOS, note 52, 29–30.

65 Soons, note 31, 188; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 571; Sookyeon Huh and Kentaro Nishimoto, “Article 249: Duty to Comply with Certain Conditions,” in Proelss (ed), note 35, 1679, 1681.

66 O’Connell, note 18, 1028; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 571.

67 See Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 334–335. Against this view: Huh and Nishimoto, “Article 249,” note 65, 1681; Wegelein, note 35, 192.

68 Montserrat Gorina-Ysern, “International Law of the Sea, Access and Benefit Sharing Agreements, and the Use of Biotechnology in the Development, Patenting and Commercialization of Marine Natural Products as Therapeutic Agents” (2006) 20 Ocean Yearbook 221, 244.

69 Soons, note 31, 406; Tanaka, note 31, 438.

70 Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 324–328; DOALOS, note 52, 38; Coelho, note 6, 516–519.

71 Soons, note 31, 188; Stephens and Rothwell, note 24, 571; Huh and Nishimoto, “Article 249,” note 65, 1681.

72 Huh and Nishimoto, “Article 249,” note 65, 1687.

73 Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 335.

74 Ibid; Huh and Nishimoto, “Article 249,” note 65, 1685; DOALOS, note 52, 43; Soons, note 31,189.

75 DOALOS, note 52, 43.

76 Gorina-Ysern, note 29, 335.

77 Yoshifumi Tanaka, A Dual Approach to Ocean Governance: The Cases of Zonal and Integrated Management in International Law of the Sea (Ashgate, 2008), 21–24.

78 Philomène Verlaan, “Experimental Activities That Intentionally Perturb the Marine Environment: Implications for the Marine Environmental Protection and Marine Scientific Research Provisions of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (2007) 31 Marine Policy 210, 211; DOALOS, note 52, 72–76; Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), Judgment (2010) ICJ Rep p. 14 [204]; Certain Activities Carried out by Nicaragua in the Border Area (Costa Rica v Nicaragua) and Construction of a Road in Costa Rica along the San Juan River (Nicaragua v Costa Rica), Merits (2015) ICJ Rep p. 665 [104] and [153]; Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion (2011) ITLOS Rep p. 10 [145].

79 Coelho, note 6, 511–516; Salpin, note 17, 153.

80 Wegelein, note 35, 238; Sookyeon Huh and Kentaro Nishimoto, “Article 253: Suspension or Cessation of Marine Scientific Research Activities” in Proelss (ed), note 35, 1700, 1701–1702.

81 Ibid, 1705.

82 Long, note 63, 479.