ABSTRACT

Excavation of a postulated early Medieval hermitage near Crowland, England, identified a site with a long and complex chronological sequence. During the Neolithic or Early Bronze Age, a monumental henge was built, among the largest so far identified in the Fens of eastern England, probably later adapted into a timber circle. After a period of apparent abandonment, the interior of the henge was reoccupied around the 7th century a.d. and, after further early Medieval phases, was transformed by the abbots of Crowland through construction of a high-status hall and chapel complex in the later 12th century a.d. While no conclusive evidence was found for an early hermitage that local tradition associates with the eremites Guthlac and Pega, Anchor Church Field offers an exceptional case study of an evolving sacred landscape in a deep-time perspective, culminating in its redevelopment by the Anglo-Norman monastery to claim legitimacy from illustrious saintly forebears.

Introduction

Around the year a.d. 700, a monk called Guthlac sought out a solitary place in the wetland landscape of the Fens of eastern England, where he established himself as a hermit. Guthlac had taken holy orders only two years previously, after giving up his career as a successful warrior, but quickly became dissatisfied with what he considered a lack of austerity in the monastic life at Repton, Derbyshire (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci Ch. 19–25). That we know so much about Guthlac is largely due to the existence of the Vita Sancti Guthlaci (Life of Guthlac) written shortly after his death. An incredibly detailed account for the period, the Vita outlines how the saint chose the watery place of Crowland as his eremitic home, where his biographer says he overcame numerous spiritual battles with demons, monsters, and even the Devil himself. According to the Vita, after leading a blameless life of Christ-like devotion and abstinence, Guthlac died in a.d. 714 and, after finding his body incorrupt after 12 months, was placed in an above-ground tomb that was later embellished with “wonderful structures and ornamentations” (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci Ch. 51–53). Fundamental to Guthlac’s posthumous veneration was his sister Pega, herself a hermit in the region, who ensured the foundation of a community dedicated to preserving her brother’s memory (Prior Citation2020, 327–330). The ultimate success of Guthlac’s cult had a profound impact on monastic development in the Fens, and the income through pilgrimage it yielded is partly responsible for Crowland Abbey’s emergence as one of England’s great Benedictine houses following its foundation in the 10th century a.d. (Roberts and Thacker Citation2020, xxiv).

Although the Vita ostensibly provides a rare and valuable biography of an early hermit, its author, an otherwise obscure individual called Felix, was writing in a hagiographic tradition that draws much of its contents from earlier saints’ lives. Far from a reliable presentation of events, the document instead is a classic contemporary account of a lone Christian hero struggling against agents of evil, and virtually every chapter can be subject to exegetical interpretation (see Thacker Citation2020). This has not prevented scholars from attempting to locate elements of the story in the landscape, especially at Crowland, with archaeologists understandably drawn to the Vita’s depictions of the built environment. Scholars of various disciplines have been especially engaged by Felix’s reference to Guthlac building his hermitage in the side of “a mound of clods built of earth” (tumulus agrestibus glaebis coacervatus), a feature previously broken into by “greedy comers to the waste” (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci Ch. 28). This passage has overwhelmingly been interpreted as a description of the saint’s reuse of a robbed-out barrow, a motif further built upon in the poems known as Guthlac A and Guthlac B (cf. Roberts Citation1979; Hall Citation2007; Semple Citation2013, 149–153).

The reference to Guthlac’s sepulchral home has motivated scholars for generations to find the appropriated barrow, with a site known as Anchor Church Field regularly touted as a likely location. Situated 1 km northeast of Crowland Abbey and the town center, local tradition stretching back at least to the 17th century a.d. associates Anchor Church Field with both Guthlac and Pega. Previous work, including antiquarian observation, as well as survey and evaluation trenching in the early 21st century a.d., confirms the significant archaeological potential of the site. Investigators have recovered material culture suggesting occupation at numerous points from the late prehistoric to the post-medieval period, but the lack of comprehensive excavation has prevented any real understanding of the chronological sequence.

Realizing both the exceptional opportunity to research archaeologically the site of a possible early Medieval hermitage, as well as the continued detrimental impact of agricultural activity upon deposits, two seasons of excavation led by the authors were undertaken at Anchor Church Field in 2021 and 2022. This work revealed a place with a remarkably long chronology that includes a previously unidentified Neolithic or Early Bronze Age henge of truly monumental proportions. The site was again the focus of ceremonial activity in the Middle Bronze Age when the earthworks of the henge appear to have been enhanced with a timber circle and numerous barrows were constructed in the vicinity. By the early medieval period, Crowland would have been widely-recognized for its monumental prehistoric earthworks and was an obvious choice for hermits to recast into a new form of Christian “holy island.” At Anchor Church Field itself, a density of medieval occupation beginning as early as the 7th century a.d. was concentrated within the still-visible henge, culminating in the second half of the 12th century a.d. with the construction by Crowland Abbey of an elaborate hall and chapel. It is impossible to place via archaeology individual hermits on the site or the communities that followed them, but repeated investment clearly demarcates a place deemed worthy of lasting veneration. In other words, later generations of clerics recognized Anchor Church Field as a place of genuine antiquity that was fundamental to the memory of their ascetic founders, irrespective of the historical reality. This article provides details of the evolution of the site as revealed through our excavations, allowing us to trace the making and repeated reshaping of a “holy” place, and closes with an assessment of the significance of these findings for understanding multi-period sacred landscapes in a broader chronological and international context.

Local Tradition and Previous Investigation

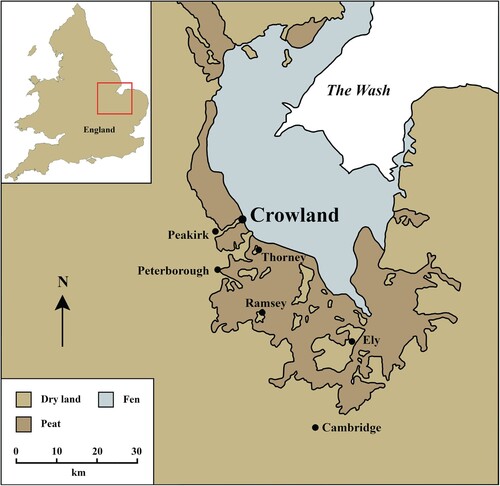

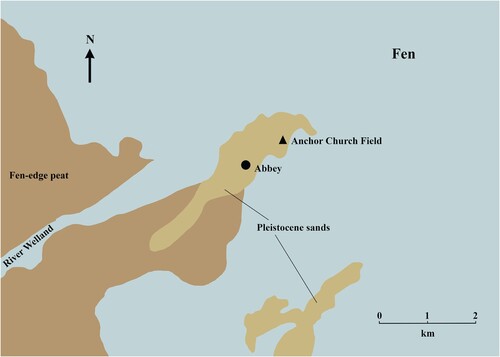

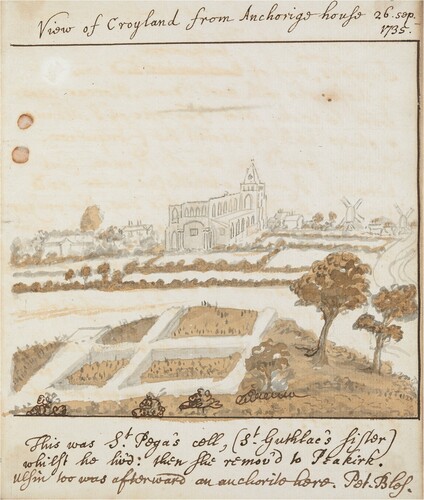

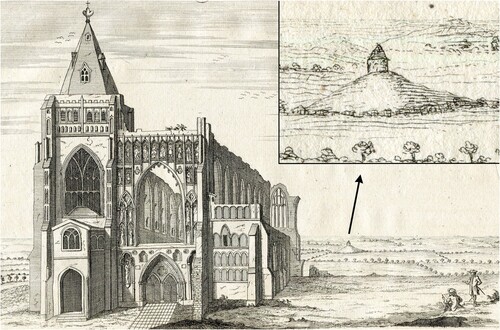

Before reclamation of the Fens, the rise on which the historic settlement of Crowland developed was situated on a peninsula jutting out into the wetland and was joined to the mainland farther west by a narrow ridge of gravel (). Surrounded on three sides by water, written accounts demonstrate that Crowland was more regularly approached by boat than via the isthmus and as a result became firmly conceptualized as an island (Hall and Coles Citation1994, 74, 192). Anchor Church Field itself is situated on a ridge projecting northeast from this “island” on land rising to 3 m above sea level (). As the most easterly part of Crowland, and a place where the habitable land met the waters of the fen, in the past this salient point would have been distinctive in the local topography. The name “Anchor” is almost certainly derived from “anchorite” and has been linked with the area since at least a.d. 1650, when the field name “Anchor Church” is recorded (Nichols Citation1793, 210). More explicit references to particular hermits are known from the early 18th century a.d.; in a.d. 1708, renowned antiquarian William Stukeley drew a domestic residence and noted that “upon a hillock, is the remnant of a little stone cottage, called Anchor church-house: here was a chapel over the place where St Guthlac lived as a hermit and where he was buried” (Stukeley Citation1776, 34). Stukeley later made another drawing of the “little stone cottage,” now ruined, with walls of a multi-celled building situated on a pronounced mound (). Somewhat confusingly, Stukeley annotated this sketch with “View from Anchorige Hill. This was Pega’s cell.” The antiquarian also suggests that the site was not merely a place of local interest but was widely recognized as a sacred place in eastern England: “to us that were brought up at Cambridge [University], and to us that live at Stamford [Lincolnshire], it is the most respectful piece of ground in the kingdom” (Gresley Citation1856, 3). Other commentators have since emulated Stukeley, suggesting that the site was used by either Guthlac, Pega, or perhaps both hermits (cf. Stocker Citation1993, 104–105; Prior Citation2020).

Figure 1. The location of Crowland on the western fen edge, with other key sites mentioned in the text (authors, adapted from Oosthuizen Citation2016).

Figure 2. The early Medieval topography of Crowland “island” (authors, based on Geological Map Data BGS © UKRI 2024).

Figure 3. Stukeley’s view of Anchor Church Field, 26th September 1735 (British Library MS 51048, f. 57r).

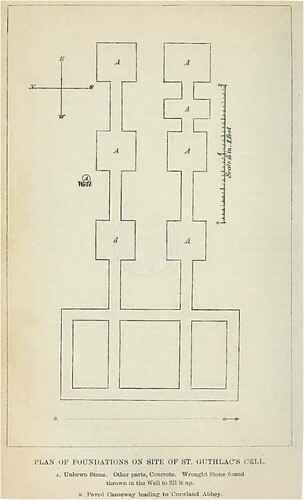

The tumulus, prominent in Stukeley’s time given both his drawing and his “upon a hillock” description, was still visible as “a slight, un-surveyable mound” as recently as 1965 (Lincolnshire HER No: MLI23230. Citationn.d). The presence of the earthwork, and the other conspicuous building remains on the site, partly explains the long-held local belief that Anchor Church Field represents the site of Guthlac’s barrow-hermitage, but this was clearly not an isolated feature in the landscape. In a.d. 1880, antiquarians “took down” a tumulus that was “one of a series which are situated in a line running directly northeast from the Abbey to the hill in Anchorage Field,” a reference that suggests a Bronze Age barrow cemetery once occupied the axis of Crowland’s northeastern ridge (Hayes and Lane Citation1992, 197). Only a year earlier, Canon Moore had published a report detailing the removal of building stone at Anchor Church Field, a site that he too believed represented Guthlac’s original cell, alongside a plan of the structures that had been revealed (Moore Citation1879) (). While Moore’s plan contains inaccuracies, his description that “prior to this act of vandalism the site was a cultivated mound” (Moore Citation1879, 133) corroborates Stukeley in its portrayal of a building constructed into or over a prominent earthwork, most probably a barrow.

Figure 4. The illustration of structures at Anchor Church Field drawn by Canon Moore, who believed the site to be “Guthlac’s cell.” While elements of the plan prove useful, our excavations make clear that Moore conflated two buildings into one on this plan (Moore Citation1879).

The presence of significant archaeological remains on the site was also demonstrated in 2002 through a combination of geophysical survey and analysis of aerial photographs undertaken by English Heritage. This work confirmed the presence of one definite ring ditch immediately east of Anchor Church Field and not one but two buildings surrounded by a rectilinear enclosure (Linford and Linford Citation2002). A subsequent program of fieldwalking and evaluation excavation in 2004 by Archaeological Project Services sought to explore the archaeology more fully and assess the preservation of what was clearly a highly plough-damaged site (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004). In addition to confirming substantial truncation, including the identification of stone wall debris and hearths amongst the plough soil, the most important outcome of the fieldwalking was the recovery of large quantities of Roman ceramic building material, the majority of which had been cut into rough tesserae (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004, 8). While trial trenching was also important in confirming features spanning the Bronze Age to post-medieval periods, the limited nature of all previous interventions has not allowed a clear picture of past activity at Anchor Church Field to be gained. In order to resolve this, and in the hope of recording the archaeological remains before their total destruction, the authors coordinated a fieldwork strategy comprising open area excavation of both buildings and targeted evaluation of potentially significant features located by previous research. The results of this program are presented here chronologically, beginning with the prehistoric use of the site.

The Henge and Other Prehistoric Activity

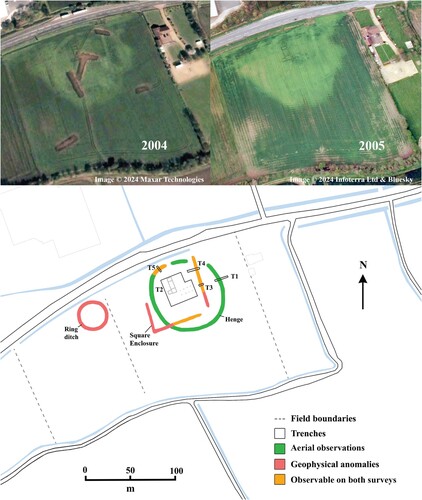

One of the evaluation trenches (Trench 1), measuring 10 × 3 m, was located over a feature visible on some aerial photography and satellite imagery. This extensive anomaly had been picked up by previous investigators but, presumably misjudging its scale, they had repeatedly labelled the feature as a ring ditch and interpreted it as a barrow (e.g. Lane Citation1988). Closer examination reveals a circular anomaly of very different composition to a barrow, measuring approximately 75 m in diameter and surrounded by a ditch approximately 5 m wide (). To evaluate this feature, a trench was positioned over the ditch on its eastern side and excavated to a maximum depth of 1.3 m, after which it was not safe to continue further. A second attempt to bottom the ditch was made through excavation of a wider trench in the northwestern corner of the circuit (Trench 5), but again this effort was unsuccessful. While the entirety of the feature was therefore not exposed, the excavation of Trench 1 in particular was still sufficient to allow characterization of the date and form of the feature.

Figure 5. Top: satellite imagery of Anchor Church field in 2004 and 2005 (© Maxar Technologies and Infoterra Ltd & Bluesky). Note the recently backfilled evaluation trenches. Bottom: Plan of trench locations and archaeological features at Anchor Church Field. Features were located through a combination of geophysical survey (Linford and Linford Citation2002), satellite imagery (Maxar Technologies and Infoterra Ltd & Bluesky), and our excavations.

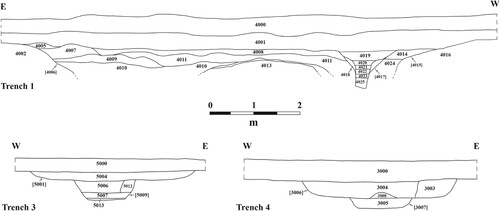

Excavation of Trench 1 confirmed the presence of a ditch running southeast to northwest through the middle of the trench (). Cut into lenses of natural glacial sands and gravels, the ditch was 9 m in width, although this has no doubt been exaggerated by later erosion. The earliest fill encountered was a shallow deposit of apparently redeposited grey-brown clay, overlain by various lenses of sands and clays. At the eastern edge of the trench were three successive fills of near-identical orange-grey loamy sands, originating just east of the ditch and representing the gradual erosion of an external bank. This bank had been constructed from the natural glacial sands, presumably the fill of the ditch when it was first excavated. Overlying the eroded bank fills, and extending across the whole of the upper ditch, were two final fills, the latter of which was an orange-grey sand that probably represents a final deposit once erosion had ceased.

Figure 6. Ditch sections from the henge (Trench 1) and early Medieval enclosure (Trenches 3 and 4) (authors).

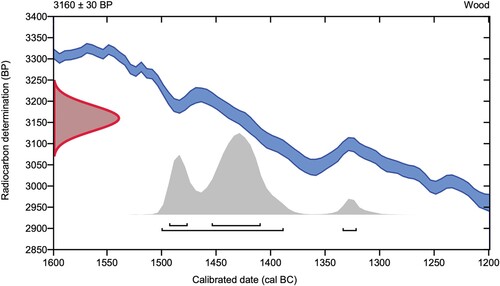

A single posthole (context 4017), surrounded by packing clay (context 4018), was cut into this surface 80 cm from the western edge of the ditch. Small fragments of decayed waterlogged wood were increasingly encountered in the fills as they were excavated. Those from the lowest fills included the curved outer surface of the original post, which was ca. 25 cm in diameter, consistent with the excavated post pipe. The post wood has been identified as being made from ash (Fraxinus excelsior), and the slight curve of the rings indicates it was formed from a large branch (E. Simmons, personal communication 2023). The post clearly rotted in situ, representing the final phase of activity in the trench, being sealed by a 30–35 cm thick band of alluvial clay and the modern plough soil. No datable finds were recovered from the ditch, and in the absence of excavated primary fills, even if present, these would not have indicated a date of construction. A fragment of the post wood, however, was 14C dated to 1502–1323 b.c. at 95.4% probability and 1495–1411 b.c. at 68.2% probability (Beta Lab. No. 664348) (). This dating demonstrates that by the early Middle Bronze Age, the majority of the ditch had already become gradually filled in and the outer bank had severely eroded or had even been deliberately levelled. Whilst the timeframe over which this took place is not possible to determine, it must represent a period of several centuries.

Given the diameter of the feature and the proportions of its ditch, in addition to the presence of an external bank and the Middle Bronze Age post cut into its upper fill, it is clear that the feature is a henge constructed in the Neolithic or Early Bronze Age. Henges are not unknown on the fen edge, such as the complex at Maxey, Cambridgeshire, but most are far smaller than the example at Crowland and are generally seen as short-lived and less impressive than those found in regions like Wessex (Pryor and French Citation1985). The henge at Crowland, though, is of an altogether different scale and monumentality than those typically present in the region, indicating a complex of some significance. Crowland’s watery topographic setting, situated at a narrowing between two watercourses to the north and south and bounded by fen to the east, was no doubt influential in the siting of the henge. Indeed, the vast majority of henges in Britain and Ireland were either totally or mostly bounded by water (Bradley Citation1993, 109–110), and at Crowland, the use and perception of the monument probably varied with the seasons; winter flooding and the rise of the water table may have led to filling of the ditch and emphasized the sense of a special “island” in the landscape. Additional investigation of the Crowland henge is no doubt required to clarify this picture, but the entranceways of the monument may also have been orientated to the directional flow of adjacent rivers in a similar manner to those in the Milfield Basin, Northumberland (Richards Citation1996, 327–329). One apparent break in the northern part of the circuit that may represent an entrance is discernible on aerial photographs and satellite imagery, although how this feature correlates with the fluvial conditions of the late prehistoric is unclear.

Although only a single post was identified in the narrow confines of the evaluation trench, its identification suggests that the henge remained a focus of ritual activity until at least the 14th century b.c. It is impossible to know whether the post stood in isolation or if it was part of a larger structure, but its positioning on the inner face of a still-visible ditch makes it tempting to see this as one element of a timber circle focused on the earlier monument. If this is the case, then the timber circle would have been incorporated into a more extensive Bronze Age ritual complex, with broadly contemporary barrows lining the peninsula, including one immediately west of the site, and terminating at the refurbished henge. The most easterly of this group may have been located within the henge itself, although an early Medieval origin for this feature cannot be discounted (see below). Irrespective of provenance, our interventions were unsuccessful in locating any stratigraphic evidence that could be related to a barrow, and despite the existence of an identifiable mound into the second half of the 20th century a.d., it sadly seems that the feature has been entirely ploughed-out over the course of the past six decades. Crucially, however, our excavation of prehistoric features did convincingly show that the henge would have remained visible into the early modern period. Whereas the eastern part of the ditch was gradually filled with silts over time, a process that at least would have muted its profile and perhaps obscured it altogether, excavation of Trench 5 in the northwestern corner of the circuit recovered large quantities of post-Medieval pottery within a series of apparent dumps. The ditch of the western part of the henge, then, not only survived but seems to have remained deep enough to inconvenience farming into the post-medieval period, leading to its infilling. The duration of the henge is fundamental to Anchor Church Field’s later development; when the site first came to be reoccupied in the early medieval period, this was a landscape with a long and conspicuous past.

Early Medieval Occupation

After the Bronze Age, the henge seems to have undergone a period of abandonment, and it is only in the early medieval period that Anchor Church Field again saw an increase in activity. A post-Roman presence was first established via fieldwalking and evaluation trenching when quantities of pottery and a number of contemporary features were identified (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004). The recent open area excavations (Trench 2) recovered substantial further quantities of ceramic, a high proportion of which were Maxey Wares of the 7th–9th centuries a.d. (Blinkhorn Citation2022, Citation2023), and two bone combs of Ashby Type 12, datable to the 6th–9th centuries a.d. (Ashby Citation2006, 107–108). Four fragments of glass were also found, and although too fragmented for precise reconstruction, it is clear they come from thin-walled drinking vessels typical of the late 7th to early 9th centuries a.d. (Broadley Citation2020) (). Such vessels are associated exclusively with high-status activity in this period and have been identified at documented ecclesiastical sites such as Glastonbury Abbey (Willmott and Welham Citation2015) and at places where an early Christian presence has been conjectured, such as Flixborough, Lincolnshire (Evison Citation2009) and Brandon, Suffolk (Evison Citation2014).

An alternative possibility is that this vessel glass is from a funerary rather than settlement context and, while the evidence for a mound is insecure, it may even originate from a primary or secondary barrow burial on the site. Prehistoric tumuli were regularly repurposed for inhumation in the early medieval period (cf. Williams Citation2006; Semple Citation2013; Mees Citation2019), including in the Fens, as at Eye where in a.d. 1984, a furnished female burial dating to the 6th century a.d. was found inserted into a Bronze Age barrow (Hall Citation1987, 6). The idea that the glass originated from a furnished grave or graves is conjectural, however, not only due to the lack of excavated evidence for a barrow but also because, along with almost the entirety of the material dated to the 7th–9th centuries a.d., it was not recovered from a stratified context but from the ploughsoil. While this “floating” corpus clearly constrains interpretation, the sheer density of the pottery of this date, comprising a third of the overall ceramic assemblage, is striking, especially when one considers how these centuries in England are usually viewed as finds-poor (e.g. Wright Citation2015, 109). Anchor Church Field between the 7th and 9th centuries a.d. seems, therefore, to have been a place of either intense or prolonged activity, or perhaps both, but is otherwise a period that belies characterization. Certainly, our excavations located no clear structural evidence for a hermitage of this date and nothing that convincingly substantiates the traditional associations of the site with the celebrated saints Guthlac and Pega.

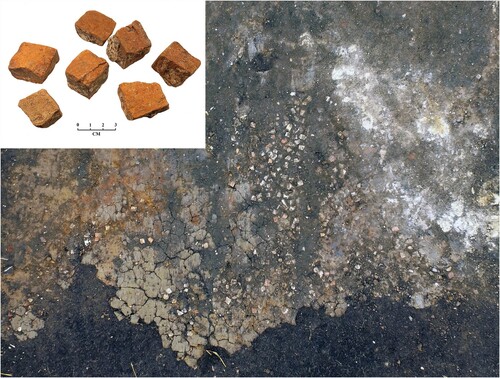

Recovery of vessel glass nevertheless indicates elite use, a concept supported by the possible presence of one or more substantial buildings on the site or in the immediate vicinity. The first piece of evidence for a structure was the recovery of considerable quantities of ceramic building material during our work, including pieces of box flue and course-cut tile tesserae similar to those observed in 2004. It had previously been assumed that this assemblage originated from Roman features on site (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004, 1), but our interventions throw doubt on this view. Over 9 kg of Roman ceramic building material were recovered in 2021–2022, the majority from a single and coherent dump, but actual occupation of the site in this period is countered by the almost total absence of pottery; only two unstratified and abraded pieces were found in two seasons. This contradictory picture strongly implies that the Roman material had been brought here selectively, most probably as a result of robbing of one or more nearby buildings.

The form of the material, and the context in which they were found, supports this reading; most pieces of tesserae retained mortar on their edges and had abraded upper surfaces, implying that they had been lifted from a previously-laid floor surface. Adjacent to the tesserae dump, a deposit of soft, highly degraded mortar shows that the tile was being cleaned on-site (). Other pieces were originally pieces of tegula, recognizable by their distinctive projecting flange, that had been hewn into rough cube tesserae. Our excavations detected no firm evidence to date robbing and recycling, nor did it locate where this material was being incorporated, but the magpie-like approach to reuse of Roman building material, especially for use in elite buildings, is widely recognized in early Medieval England. The phenomenon is especially well-documented in churches of the period, but research is increasingly showing this practice was not the preserve of ecclesiastics. Recent work by Gabor Thomas, for instance, has outlined in detail the processes of reuse and reincorporation in the 7th century a.d. great hall complexes of Kent. The evidence for such “hybrid” monuments, Thomas argues, not only severs the timber-stone distinction that has been so central to interpretation of early Medieval architecture in England but also illustrates that the boundary between religious and secular spaces was more mutable and porous than often appreciated (Thomas Citation2018, 294–295). However and wherever the Roman spolia was deployed at Crowland, its use is unlikely to have been motivated purely by pragmatism but instead was a process, as we see elsewhere in Europe, in which the symbolic sanctity and power of Romanitas was deliberately appropriated. Indeed, the authority inferred onto new buildings and their commissioners by Roman material may have been equally potent to that provided by prehistoric monuments (cf. Semple Citation2013, 132–136). As in contemporary Kent, Anchor Church Field may have been a place where the process of sacralizing and legitimizing was derived from a variety of past features in the landscape, carefully curated through hybrid building practices.

Where the early Medieval building(s) was located is again uncertain, but the most likely location is within a substantial enclosure first identified by geophysics and evaluated by excavation in 2004 (see ). This almost perfectly regular feature was formed by a substantial ditch and originally assigned a 9th–12th century a.d. origin on the basis of ceramic finds. Both the southern and eastern arms of the square enclosure seem to span the circuit of the henge, but the exact relationship between the two features is not clear. Furthermore, gaps in the geophysical anomalies in the southeastern and northwestern corners of the enclosure raise the possibility that ditches did not run along the entirety of the circuit and that a more composite construction may have existed. If the enclosure was complete, it would have measured approximately 75 m in length on all sides and is centered on the most elevated part of the site around the 3 m contour. In an effort to verify the provenance of the feature, its eastern extent was the focus of two evaluation trenches (see , Trenches 3 and 4). These interventions revealed ditches formed by a similar arrangement of cuts and fills, from which a broad stratigraphic and chronological sequence can be constructed. The first phase of the ditch was defined by a narrow cut with a flat base between 80 and 90 cm wide with a primary fill of homogenous mixed loam-clay. In both instances, this fill was archaeologically sterile and thus probably represents the initial erosion of the ditch cut (see ).

The first ditch was truncated by a second, larger recut measuring between 2.7 and 3 m wide, again with a flat base. The filling of this recut differed somewhat between trenches, and in the northern trench, it is possible that packing was laid to accommodate a sleeper beam. Such construction techniques are not usually associated with enclosures during this period, and it is possible that the sleeper formed part of a small bridge spanning the ditch. Dating this sequence is somewhat tentative, but the first phase ditch was established by at least the 9th or 10th century a.d., as indicated by St. Neots and Stamford Wares in its upper fill (Blinkhorn Citation2022). Given the absence of datable material from the primary fills, though, it is possible that the original cut was made some time before these ceramics accumulated and could push the dating back to before the 9th century a.d. The recutting and broadening of the ditch took place by the 12th century a.d. at the very latest, based upon the presence of unabraded South Lincolnshire Shelley Wares in its fill, and apparently remained open into the post-medieval period, as early red earthenware were present in the uppermost lenses.

Our excavations, therefore, located an array of early Medieval evidence at Anchor Church Field and, although the manner of occupation in the 7th–9th centuries a.d. is obscure, it is plausible that activity was defined not only by the earthworks of the henge but also by a square, ditched enclosure. The enclosing features may have served as the focus for one or more structures that feasibly incorporated recycled Roman building material, being processed on-site, into their fabric. The square enclosure could have originated as late as the 10th century a.d., however, and both the broad dating and the ephemeral nature of the archaeology inhibits reconstruction of Anchor Church Field’s early Medieval phases with any real clarity. If pre-Conquest buildings were present on-site, it is likely they would have been positioned centrally within the square enclosure; unfortunately, it is this same area that was transformed in the second half of the 12th century a.d. in a comprehensive redevelopment that seemingly removed much of the evidence for early Medieval occupation.

The Monastic Hall and Chapel

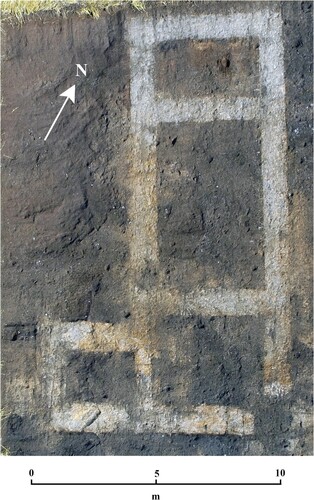

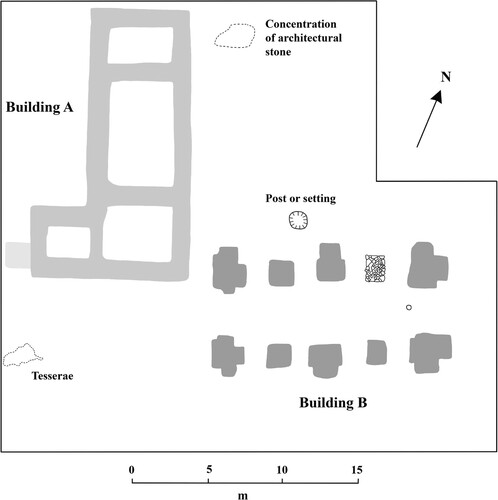

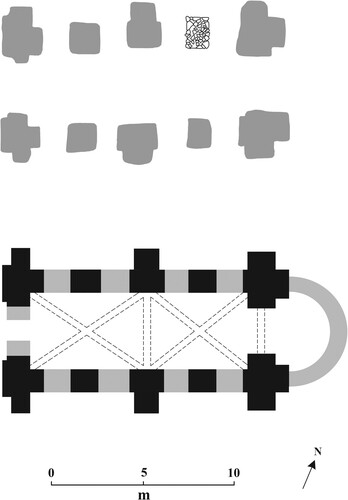

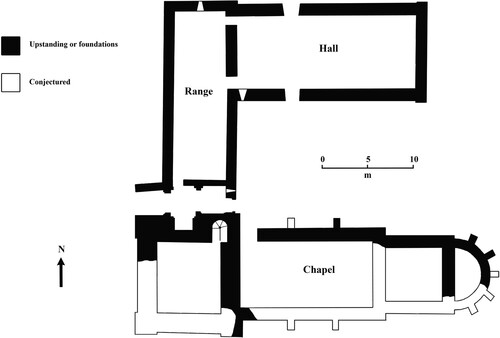

By far the most conspicuous feature on aerial photographs and geophysical survey of Anchor Church Field is the outline of a substantial structure, divided into three cells (Building A) (see , ). Positioned perpendicular to this building, a second more ephemeral structure of a different construction type had also been located by previous work (Building B) (see , ). The two structures were located roughly in the middle of the square enclosure, fully encompassed, too, by the earthworks of the henge (see , ). The southeastern corner of Building A was sectioned as part of the 2004 evaluation trenching when it was described as “a foundation trench … filled with a highly compacted sand” (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004, 6–7). Our more comprehensive excavation of the building and an open area to the south, though, suggests this observation is inaccurate. Instead, the structure was found to be made of upstanding wall, severely truncated through ploughing, situated within a shallow foundation trench. Externally, the building had been faced with large stones, and although none remained in situ, there was in many places a soft soil between the wall core and the surrounding deposits, a result of later robbing. Building A was 17.2 m long and approximately 7 m wide, divided into three principal units, with an additional unit measuring 4 × 4.8 m on its southwestern side (see ). The external walls were consistently 1.2–1.3 m thick, whilst the internal divisions were between 0.9 and 1.2 m wide. The wall consisted of a mixed yellow/white mortar, compacted sand, and small stone.

In spite of excavating eight sections across the wall and foundation trench, no directly datable material was recovered from these contexts. The consistent form of the structure, though, hints at a single phase of construction that pottery from the interior broadly places in the 12th or 13th century a.d. This date, together with its three-cell construction, immediately identifies the building as a Medieval house almost certainly arranged with a hall at its center, services at its northern end, and two upper-end chambers and a garderobe to the south. The presence of an additional unit at the southwestern corner demonstrates that the chambers and garderobe were situated within a cross-wing. Internally, the hall would have been open from ground level to rafters, but both the northern and southern extents would have been two-storeyed. Stone halls such as this are known in Britain from the middle of the 12th century a.d., becoming more commonplace in the 13th century a.d. (Grenville Citation1997, 89–99). An earlier date within this range, ca. a.d. 1150–1200, is preferred for the construction of Building A based upon the building stone recovered immediately east of the hall (see below). A parallel to the form and date of Building A can be found at Weeting “Castle,” Norfolk, which despite the name is an unfortified house probably built around a.d. 1180. At Weeting, however, the chamber and latrine were situated inside an even more impressive block of three storeys (Heslop Citation2000). Integrated, stone-built houses of this date are nevertheless rare and are found only in the grandest contexts, such as royal and episcopal residences (Hill and Gardiner Citation2018a, Citation2018b). The presence of such a structure at Anchor Church Field is thus a substantial and conspicuous investment from the upper echelons of society, the context for which is explored further below.

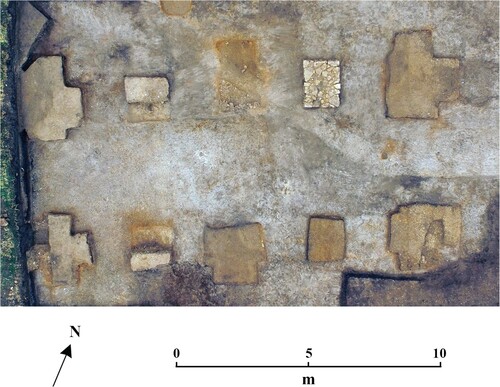

Perpendicular to the hall, a second building (Building B) had also been located by earlier work, visible on aerial images as two sets of parallel, west-east orientated features and identified by geophysics as high-resistance anomalies. Until now, however, it had not been observed that the arrangement of two perpendicular buildings makes clear that Moore had conflated them into a single structure on his plan (see ), possibly as his knowledge of the site was relayed through an intermediary and some years after robbing took place (Moore Citation1879, 133). Trial trenching in 2004 uncovered the corner of one of the high-resistance anomalies that proved to be made up of roughly coursed stone and was interpreted as a column base (Cope-Faulkner Citation2004, 6, pl. 6). To fully characterize Building B, the whole area was subject to excavation in 2022 to include the locations of all other potential column bases. On removal of the ploughsoil, numerous mixed deposits and multi-period pottery represented upcast from robbing, almost certainly that documented by Moore. So thorough was this effort that no walling of the building could be identified, and no floor or other surfaces remained intact. Less than half a dozen pieces of stone remained with evidence of tooling. The only features that had escaped the demolition were nine hard-set white mortar blocks incorporating small pieces of rubble, measuring 2 m2 minimum. A tenth block, uncovered in the earlier evaluation, was a different construction type of clay-bonded, unworked stones with flat outer edges. Together, these 10 features were set in pairs and can be confirmed as the bases for substantial columns. Those bases at the corners and mid-point of the building had short protruding elements, suggestive of buttressing, whilst those in between were more regular. All the buttresses, except one, were set into a shallow (< 15 cm) solid natural clay layer. The only exception was at the western end of the structure, where a significant quantity of flint debitage pressed into the clay may represent a prehistoric surface.

The only other internal feature in direct association with this building was a single shallow, rounded posthole ca. 15 cm in diameter set exactly midway between the western faces of the easternmost bases. A speculative purpose for this feature, based upon its precise positioning, is to accommodate a laying out post (M. Gardiner, personal communication 2023). External to the building, and possibly associated with it, was a sub-circular pit 1.1 m in diameter. When uncovered in the early 19th century a.d., this feature was clearly stone-lined and recorded as a well. The pit is too shallow and above even the historic water table to act effectively as a well, however, and given the nature of the buildings surrounding it may be better viewed as the base for a flagstaff or more likely as a setting for a monumental cross. It is notable that this feature is located in an area that would have represented the front elevation of the two buildings, making it highly visible to visitors to the site, who would have accessed the complex along the ridge from the north and entered the complex via a break in the circuit of the henge.

All of the column bases of Building B were half-sectioned, in four of which Bourne “A” Wares of mid-12th–14th century a.d. date were found (Blinkhorn Citation2023). No datable material was found in the single stone base, but its different construction suggests a later replacement for an earlier rubble and mortar feature. It is notable that this replacement is located on the eastern side of the structure in an area of the complex most liable to flooding and thus probably the end of the building at greatest risk of subsidence. The broad phasing offered by the pottery from the buildings can be refined further by the excavated carved stone found dumped immediately east of the hall. Among this assemblage was an en-delit shaft probably deriving from a doorway with elaborate architrave, a section of an external reveal from a narrow-looped window, and an ashlar block. This material is obviously from an elite building, dated to ca. a.d. 1150–1200 by the form of the en-delit shaft and the use of an undecorated blade on all pieces (D. Stocker. personal communication 2023). Also among the assemblage of dumped material was a large quantity of elaborately sculpted pieces of highly oolitic limestone, perhaps originating from foliate or even figural carving. Much of this material has a curving profile, hinting that it once formed part of a screen such as a tympanum or reredos, but equally it could come from a free-standing sculpture. The purpose of these fragmentary and weathered pieces cannot be extrapolated further, however, and they may even be Roman rather than Medieval in origin.

It is highly significant for our interpretation of the site, and Building B in particular, that we have convincing evidence that the entire assemblage of worked stone derives not from the robbing reported by Canon Moore but instead from an episode of Medieval demolition. Found in context with the stonework were a number of pieces of Bourne “A” Wares (12th–14th century a.d.) and Lyvenden/Stanion “B” Ware (13th–14th century a.d.), all of which was sealed by later ploughsoils. This pottery provides a terminus post quem of the 13th century a.d., and although we cannot be sure how long after this date demolition took place, it suggests that one or both of the 12th century a.d. buildings at Anchor Church Field had a relatively brief life-span of perhaps one or two centuries. We believe that the material, however, derives only from Building B and that this structure represents a chapel built alongside the hall in a single construction phase during the later 12th century a.d.

The sketch made by Canon Moore suggests that Building B once had narrow walls connecting the pier bases on both its northern and southern sides. This aisle-less plan, along with the sheer size of the bases, implies a vaulted building in a two-bay, quadripartite arrangement with the larger, buttressed piers receiving the diagonal ribs (). The lack of buttresses on the smaller piers indicates that they were not built to receive the weight of the vault but instead acted as support for the walls. Further backing for this hypothesis is the existence of the replacement pier: if this feature was bearing the load of the vault springing, replacing it in such a fashion would have been a major and potentially hazardous operation. Such a replacement obviously implies significant problems with the eastern end of Building B, perhaps in an early stage of its existence judging by the broadly Medieval form of the new pier. While the vaulted form, that was common in both religious and secular buildings of the time, does not confirm Building B as a chapel, the evidence for architectural failure is significant. Documentary sources identify a chapel of Crowland Abbey located “on the eastern side of the monastery,” described as no longer served by a priest in a.d. 1434 and as lying in ruins by a.d. 1440. Significantly, the recorded dedication of this chapel is to St. Pega, and the location of the building been previously determined with some confidence as Anchor Church Field (Stocker Citation1993, 105; Prior Citation2020). The archaeological evidence we have recovered aligns with this thinking, and disuse of the chapel by the early 15th century a.d. certainly provides a plausible context for the dumping of the architectural stonework found by our excavations.

Figure 13. Reconstruction of the Medieval chapel, depicting the proposed quadripartite arrangement of the vault (authors).

Together, this evidence provides a degree of confidence that Building B at Anchor Church Field is a 12th century a.d. stone-built, vaulted chapel which by the late medieval period was dedicated to Pega. England is not overflowing with examples of vaulted stone ground-floor chapels of this date, but they are commonly found in France, partly as a result of better preservation; foundations of similar detached chapels in elite complexes can be found, for instance, at the castles of Falaise and Caen, both in the Calvados region (Chave Citation2005; Decaëns, Dubois, and Allainguillaume Citation2010). It is probable that an apse was once incorporated at the eastern end of Building B, a feature that would resolve the identity and function of the structure beyond doubt. In a similar manner to the walls connecting the columns, however, all evidence for an apse had been completely removed by a combination of 19th century a.d. robbing and agricultural attrition. At some point in its use, the eastern end of the building seems to have failed, and while a replacement pier may have sustained it for a time, in the late medieval period, part of the building at least was being stripped of architectural features. This robbing was clearly not entirely comprehensive, as evidenced by the significant quantities of stone taken by the Victorian workmen, and may even have been motivated to ensure the structural integrity of the chapel in the immediate term. The only alternative interpretation of Building B that can be sustained on the plan of the pier foundations is to see this structure as a chamber block associated with the adjacent hall. The excavated footings are certainly comparable to contemporary chambers, such as the celebrated nearby example at the manorial center of Boothby Pagnell, Lincolnshire (Harris and Impey Citation2002). The weight of evidence presented here, however, strongly supports Building B’s interpretation as a chapel rather than a chamber. Indeed, the reasons why the builders of the Medieval complex included a chapel dedicated to Pega are given a more compelling context when the development of Anchor Church Field as a long-lived sacred landscape is explored in more detail.

Discussion: Crowland as a Sacred Landscape

Archaeological approaches to the ambiguous and mutable relationship between people, nature, and the sacred have largely been pioneered by prehistorians, the studies of whom have provided a valuable stimulus to those specializing in other periods. Such cross-fertilization has gathered notable pace in the 21st century a.d., a welcome process that to some extent has “loosened the constraints of a historical framework,” especially for early Medieval archaeologists (Semple Citation2013, 8). In Europe, those investigating 1st millennium a.d. Scandinavia have led the way in reconstructing lost conceptual geographies, although the extent to which later documentary sources can be used in such efforts is now rightly treated with caution (e.g. Brink Citation2001; Price Citation2002). In spite of these positive developments, in her recent book on monasticism, Roberta Gilchrist contends that Medieval archaeologists “have not engaged sufficiently with the sacred” and that research continues to assert a humanist or secular outlook. This critique is especially pertinent to studies of later Medieval religion, where the traditional emphasis has been on the function of major buildings and on the economic and technological role of ecclesiastical institutions (Gilchrist Citation2020, 4–5). Anchor Church Field therefore represents a particularly important case study for archaeologies of the sacred, not only due to its long chronology but because it was developed as a monastic dependency rather than as the focus of a claustral complex. Together with Crowland’s rich documentary record, including a vanishingly rare Vita of an early Medieval saint, the Anchor Church Field excavations offer a remarkable opportunity to explore the development of a sacred landscape across millennia in great detail.

The identification of the monumental henge at Anchor Church Field is a significant development in its own right, yet to find that the earthworks were appropriated in the early medieval period is in many ways unsurprising. The 7th century a.d. represents a watershed in the reuse of prehistoric and Roman monuments in England, possibly as a result of elite groups and families attempting to create a sense of ancestry to consolidate their power (Bradley Citation1987; Blair Citation2005, 52). Bronze Age barrows were the most frequently reutilized monument type, but as Sarah Semple’s work has shown, a vast array of features were deployed for an equally wide range of uses, all of which argues against a common meaning or purpose. Semple goes on to argue that these diverse responses to antecedent components in the landscape was intensely localized, as individuals and communities used them to create distinct narratives to meet their specific needs (Semple Citation2013, 106–107). This is almost certainly the case at Anchor Church Field, where the weight of probability suggests that there once stood one or more barrows within the circuit of the henge, at the apex of a more extensive ridge-line Bronze Age cemetery. The picture of monument appropriation revealed through excavation correlates closely with the narrative of Guthlac’s reused barrow in the Vita Sancti Guthlaci and Guthlac A and B, the texts of which have provided fertile ground for researchers to explore the conceptual significance of burial mounds in early Medieval England (e.g. Shook Citation1960; Hall Citation2007, 218; Semple Citation2013, 149–153).

Felix’s inclusion of a tumulus (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci) and the Guthlac poems’ description of a beorg (“barrow”) (Guthlac A II, line 102), though, may also have acted as a model unrecognized by previous scholarship, deployed as an exegetical device that simultaneously rooted the narrative decisively in the local landscape. As antiquarian accounts demonstrate, Crowland was clearly distinguished until relatively recently by its prehistoric monuments, so much so that the crug element of the place-name may even derive from the British word for “hill,” “mound,” or, most compellingly, “barrow” (Higham Citation2005, 87). In her analysis of how Christian sacred places were created in the early medieval period, Helen Gittos stresses how authors of Vitae and other texts situated their stories in precise local settings, partly as a way of lifting them out of a scholarly milieu to make them accessible to a wider audience (Gittos Citation2013, 29–31). Guthlac’s burial mound performs exactly this function, locating indelibly the events at Crowland as “the place of the barrows.” Other details of the tumulus/beorg story are capable of exegetical interpretation, not least the reference to grave robbing that deliberately aligns Guthlac’s transformation of the mound into a cell with Matthew 21:13: “It is written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer, but you have made it a den of thieves’.” Other elements of the text undoubtedly correspond with hagiographical convention alone, such as Felix’s mention of a cistern, which is lifted from Jerome’s Life of Paul the Hermit rather than indicating the presence of Roman remains as some have previously asserted (cf. Colgrave Citation1956, 182–184; Meaney Citation2001, 35).

While the work of Thacker (Citation1978, 279–328; Citation2020) in particular has demonstrated that Felix was no slavish copyist of established hagiographies, the examples above, among many others, do suggest that attempts to locate events from the Vita and the Guthlac poems in the real world have lacked the required circumspection. The idea that Guthlac’s hermitage can be pinpointed as a single site loses further credibility when it is considered that in the early medieval period, the entirety of the Crowland peninsula would probably have been conceived of as the sacred core of the religious community, akin to other island/isthmus churches of this date (cf. Stocker Citation1993; Carver Citation2009, 335–336). Careful reading of Guthlac’s Vitae only emphasizes this, with a clear sense of movement in many parts of the text suggesting that the saint and his immediate followers occupied numerous locations on the habitable land. This is best demonstrated by the repeated reference to visitors arriving at the landing platform needing to sound a signal (by ringing a bell?) to summon Guthlac to meet them (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci 40, 41, 52). If the saint was to be reliably found in a single place, then any such system would be largely redundant. While we believe that it is entirely plausible, indeed likely, that any nascent religious community would have utilized the henge at Anchor Church Field as a ready-made enclosure, the site would have been one focus in an entire landscape that was being transformed into a numinous “holy island” through occupation of a multitude of settings. Felix’s use of Bede’s Life of Cuthbert, which is referenced in a very deliberate and considered manner to build his portrait of Guthlac, also speaks to this; here was not just a model of a saint and a hermit to be emulated but one that also inhabited and conquered a hostile island for the glory of Christ (Thacker Citation2020, 6–8).

As much as Felix tries to portray Guthlac as a lone warrior in a desert landscape, other evidence indicates that the Fens was a region teeming with eremitic activity in the period (see ). For example, the island of Thorney in Cambridgeshire, just 7 km south of Crowland, was first known as Ancarig or “isle of the anchorites,” and three hermit-saints, all of whom had hagiographies written of them, were venerated there (Pestell Citation2004, 136–137). A similar case can be made for Peakirk, Northamptonshire, 8 km southeast of Crowland, where a community of eremites founded by Pega may have persisted for some time (Roffe Citation1995, 93–108). Guthlac was clearly not alone in his pursuit, then, but neither does he appear to have been among the founding generation of hermits. He instead entered into a well-established, if geographically dispersed, network of peers. In the Vita, the saint is shown the way to Crowland by a local man called Tatwine, who himself was possibly a cleric of the powerful nearby monastery of Medeshamstede (Peterborough), suggesting that the peninsula was already recognized as a suitable place to send a recluse and may even have been already inhabited by hermits (Everson and Stocker Citation2023a, 10–11). The influence of Peterborough in populating the wetlands with eremites and sponsoring Guthlac in his mission has been established for some time (e.g. Meaney Citation2001, 34) but has recently been explored in fine detail by Everson and Stocker (Citation2023a). They convincingly argue that Guthlac’s settlement on Crowland is a routine example of an eremitical plantation by an adjacent Benedictine monastery, a practice recognized by John Blair as commonplace for the pre-Viking Church (Blair Citation2005, 144–145; Everson and Stocker Citation2023a, 9). The establishment of monastic institutions in the Fens was also heavily influenced by political conditions; the pre-eminent 7th century a.d. monasteries at Peterborough and Ely, situated in the territories of the North and South Gyrwe, respectively, look like directly competing foundations backed by rival royal families (Everson and Stocker Citation2023b, 54). The settlement of hermits was part and parcel of this maneuvering, and Guthlac’s role as political actor is also plainly obvious in the passages where he acts as counsellor of king-in-waiting Æthelbald (Colgrave Citation1956, Vita Sancti Guthlaci 40, 42, 45, 49, 52; Lesser Citation2020, 142).

After his death, Guthlac was buried at Crowland, but we have little insight into what the community may have looked like or how the cult was coordinated after the supervision of Pega. It is probable that followers persisted in maintaining a church-shrine on the peninsula, but any such group would have been closely controlled by Medeshamstede until Crowland’s establishment as a reformed coenobitic institution in the late 10th century a.d. (Roberts Citation2005, 143). The process of monastic foundation in the Fens is intriguing given the frequency with which locations associated with hermits, either real or contrived, were central to site selection. To places with convincing eremitic traditions can be added cases such as Ramsey, Cambridgeshire, where claims of hermits occupying the island from the 7th century a.d. look very much like a later contrivance in order to add historical weight to a novel institution (Hart Citation1994). It is around the 10th century a.d., and in the context of widespread changing perceptions of consecrated space in western Europe, that the role and status of Anchor Church Field evolved. Although all of the habitable land on Crowland would have continued to be viewed as a “holy and inviolable circle” around the monastery (Rosenwein Citation1999, 1), the site of the new and more permanent claustral building was now promoted as paramount over other sacred places. The concern of the abbey to present itself as the location of Guthlac’s hermitage and tomb would have been in lockstep with a need to style other venerated spaces as paradoxically holy but indisputably secondary in a stricter hierarchy of sanctity. Somewhat extraordinarily, we seemingly have documentary sources outlining how this phenomenon played out for Anchor Church Field; both Orderic Vitalis and the unreliable text known as the Pseudo-Ingulf suggest that before Pega’s chapel there existed a more independent community on the site, perhaps acting as a sort of school for novices, that was only amalgamated with the main abbey in the 10th or 11th century a.d. (Alexander Citation2020, 314). In contrast, the tradition that the claustral complex of Crowland Abbey represented the location of Guthlac’s oratory became firmly established, and even as late as a.d. 1746/7, Stukeley described visiting a building of “slud and clay mortar” at the western end of the south aisle that was proclaimed locally as the saint’s cell (Alexander Citation2020, 304–305).

In his recent doctoral thesis, Ross McIntire labels locations such as Anchor Church Field “secondary cult sites,” following the concept of “holy radioactivity” presented by Brian Finucane (Finucane Citation1977; McIntire Citation2019; Alexander Citation2020, 304–305). Examining evidence from Ireland, Wales, and England, McIntire shows how these hitherto understudied lesser foci remained integral to the promotion, veneration, and rhythms of pilgrimage at a variety of monastic institutions throughout the Anglo-Norman period. The Norman Conquest presented all monasteries with the challenges of a volatile social and political environment, but those like Crowland who had previously promoted Anglo-Saxon saints had a further element to mediate. The scholarship on this theme is extensive and will not be reviewed here, but in short, the consensus position now sees greater continuity of veneration across the Conquest, with numerous examples recognized of Norman clerics exploiting Anglo-Saxon saints positively (e.g. Chibnall Citation1987; Ridyard Citation1987; cf. Browett Citation2016). The extent and nature of Crowland’s veneration of Guthlac after the Conquest is similarly debated, with a dearth of miracles attributed to the saint in these turbulent decades feasibly reflecting that he was viewed as a role model of holy living rather than a supernatural intercessor (Licence Citation2020, 387–391). The 12th century a.d. was nevertheless a period in which Crowland sought to break free from the oversight of Peterborough, a strategy that included clear attempts to claim Guthlac’s unbroken presence on the peninsula; this included a newly-fabricated hagiography, a staged inventio (a narrative of how his relics were discovered), a second enshrinement of bodily relics, and concocted claims of a history of “permanent sanctuary” (Brady Citation2018; Everson and Stocker Citation2023a, 20).

The simultaneous development of Anchor Church Field as a high-status hall-chapel presents a material manifestation of this exact process, an act of commemoration that claimed ownership, first and foremost, over Guthlac’s memory (cf. Cubitt Citation2000). By aggrandizing a site that was associated, at least in contemporary minds, with Pega, Crowland Abbey derived authority both from the hermits themselves but also from a location replete with a range of conspicuous archaeological features that instilled a sense of deep and genuine antiquity. As Gilchrist suggests, the key role of a medieval monastery’s memorial function was as a mortuary landscape, and venerated figures needed to not just be referenced but physically embedded into the institution (Gilchrist Citation2020, 174). To achieve this, the most important feature to ecclesiastics was clearly possession of mortal remains, but at Crowland, reference to the surrounding landscape of tumuli would have taken on a particular resonance. By locating a hall and chapel amongst the barrow cemetery, the abbey proclaimed its credentials as a mortuary space worthy of patronage, the mounds feasibly creating a sense of continuity and thus instilling legitimacy in the same way they had in the 7th century a.d. The established narratives of Guthlac and his burial mound hermitage would have heighted the significance of Anchor Church Field’s development for the clerics, but this would also have been a profound and deeply symbolic procedure, especially as the saint himself is described as undergoing a literal death—descending Christ-like into the mouth of hell—before his resurrection and eventual victory (Colgrave Citation1956, 31).

The physical form of the 12th century a.d. hall-chapel is similar to Benedictine arrangements on other outlying sites but bears closest resemblance to Minster Court at Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, which consists of a hall to the north, range to the west, and chapel to the south (). Commissioned by St. Augustine’s, Canterbury, the site at Minster is admittedly more elaborate than Crowland, not only evidenced by its additional range but also by its overall grander scale and execution that includes a substantial square tower in its southwestern angle (Kipps Citation1929; Impey Citation1991, 66). The parallels between Crowland and Minster are not limited to architecture, however, but extend into both the context and motivation behind their commissioning. During the early 11th century a.d., St. Augustine’s was undergoing a similar process of consolidation to Crowland, including the transfer of holy relics to the main abbey site. The remains of Mildrith were translated permanently from Minster-in-Thanet in a.d. 1030, but in an attempt to placate local disapproval, St. Augustine’s offered gestures of conciliation that included celebration of one of her feast days on the island (Rollason Citation1986, 145; Gittos Citation2013, 27–28).

Figure 14. Plan of Minster Court, Thanet, which bears close resemblance to the 12th century a.d. complex at Anchor Church Field (authors, after Kipps Citation1929, pl. 1).

Establishment of Minster Court in the late 11th century a.d. is unlikely to have been part of this same strategy of appeasement, but it did provide St. Augustine’s with a permanent presence on a distant part of their estate associated with a celebrated saintly predecessor. Transformation of outlying sites with saintly associations into comfortable retreats was not limited to the Benedictines but was established practice in England, France, and elsewhere. In a.d. 1178, for example, the Abbot of St. Albans built a cell at Redbourn, Hertfordshire, following the supposed discovery of the bones of St. Amphibabalus, who was credited with converting Alban to Christianity (Impey Citation1991, 66). To some extent, then, both Anchor Church Field and Minster Court represented grand mnemonic devices, while doubling as sites of pilgrimage that could be used by abbots to entertain guests beyond the confines of the monastery. Additional functions beyond these are credible, with clerics often favoring such locations for health purposes such as bleeding. Dedicated “seney” houses were widespread on monastic estates, and elsewhere in Lincolnshire, the monks of Bardney Abbey built a specialized bleeding house in a comparably isolated setting on their peninsula monastery (Thompson Citation1913, 91–92). A similar establishment for Peterborough Abbey was located 10 km to the south of Crowland at Oxney where an earlier grange that had a parochial chapel by a.d. 1146 and a fair by a.d. 1249 was turned over to obsequies and bloodletting by the later medieval period (Heale Citation2004, 147; Everson and Stocker Citation2011, 324). At Redbourn, too, the cell of St. Albans was being used as a “health resort” from at least the a.d. 1190s (Impey Citation1991, 66).

A final impetus behind the construction of the hall-chapel at Anchor Church Field would have been provided by the changing environmental conditions on Crowland, and the Fens more widely, during the 12th century a.d. It is from this period that we have the first physical evidence for boundary markers, in the form of stone crosses, demarcating the later Medieval parish as it expanded through reclamation into the surrounding wetland (Stocker Citation1993, 101–104). Draining of the marsh immediately around the peninsula would have transformed the topographic setting of Anchor Church Field beyond recognition; the site would no longer have been distinctive as the most easterly part of the isthmus, surrounded on three sides by water, but was instead now situated amidst newly cultivable land. The establishment of churches alongside agricultural intensification is a widely recognized phenomenon in western Europe, such as in Galicia in the 7th century a.d., where expansion of farmland went hand-in-hand with the foundation of propriety churches and family monasteries. Although we are unclear of the physical character of these small monasteries, José Carlos Sánchez-Pardo’s speculation that they were “small complexes of wood and stone with a simple church” could equally be a description of the later dependency at Anchor Church Field (Sánchez-Pardo Citation2016, 376). The use of crosses to mark territory and rights over good-quality soils was also commonplace, albeit not a practice limited to ecclesiastics but which became increasingly fashionable among secular lords from the 12th century a.d. (Turner Citation2006, 49–50; Comeau Citation2016, 217–218). The consideration of the physical environment, often overlooked in scholarship of the later medieval period, therefore provides another insight into the way in which the hall-chapel at Anchor Church Field memorialized a site and institution experiencing not only major religious and political upheaval but also significant and permanent landscape change.

The fate of the buildings in the Benedictine complex seems to have diverged in the later Medieval and post-Medieval centuries, with the chapel falling into ruin but the hall being maintained, albeit in a much-modified state, as a domestic residence. In addition to the structural problems that affected the chapel, investment in the building is likely to have declined as pilgrimage waned and eventually ceased across the course of the Reformation. Our excavation of numerous tree-throws and a significant build-up of organic material suggests that the area of the chapel was given over to serve as the garden of the adjacent domestic building. The hall itself is unlikely to have maintained its high-status form or function and was definitely much altered by Stukeley’s time when he refers to it as a “cottage” of apparently no grandeur (Stukeley Citation1776, 34). Exceptionally bad preservation of the post-Medieval stratigraphy on-site does not allow us to go much further, but the cottage on the mound, to which the locals attached stories of anchorites generally, and Pega and Guthlac specifically, remained a prominent feature of the landscape and was intervisible with the abbey (). Yet, the holiness of Anchor Church Field did not evaporate entirely with the transformations brought about by its change in use or the growth of Protestantism. Writing in a.d. 1783, Richard Gough recounts how 45 years previously (ca. a.d. 1738), the occupier of the residence “and the inclosure [sic] adjoining it, William Baguley, clerk, but never a minister of the parish, frequently, and especially on Sundays went to the inclosure wherein the hill is, and immediately upon entering it, fell upon his knees, and placing his hat before his face, continued for a considerable time in a posture of adoration. This is an unprecedented instances of a protestant divine’s enthusiastic veneration for a hermit, or the ground wherein he hath been supposed to have lived, died, and been buried” (Gough Citation1783, 104). The “inclosure wherein the hill is” looks like a reference to Mr. Baguley’s garden and the site of Pega’s chapel. Whether you consider Baguley an eccentric or a devout “man of good understanding” as Gough (Citation1783, 105) did, such detail is a poignant reminder of the longitudinal influence that once-sacrosanct places can have, including upon individuals whose experiences are rarely captured by written records. It is perhaps only when Baguley had the house pulled down, shortly before he was incarcerated in a debtors prison, that the final chapter of Anchor Church Field as an active sacred space was eventually ended.

Figure 15. Stukeley’s view of the western prospect of Crowland Abbey, 14th July 1724, including a depiction of a building at Anchor Church Field located on a distinctive mound (Stukeley Citation1776, pl. 4:2d)

Conclusion

The results of our excavations at Anchor Church Field provide an unprecedented perspective on Crowland’s origins as a sacred landscape and the evolution of a place perceived as numinous at different points over millennia. While historians have understandably emphasized the significance of particular individuals like Guthlac and Pega in providing a legacy to the development of the later monastery, the archaeology gives a far greater sense of the time-depth and complexity of occupation on the peninsula from the Neolithic period onwards. It is now clear that the early Medieval hermits of Crowland entered into a particularly extensive and monumental prehistoric setting, a unique inheritance that distinguished the landscape within the wider region. This legacy in part explains the centrality of the barrow in the Guthlac narratives; here was an exegetical device that embedded purported events emphatically in the local landscape as the eremites reshaped Crowland into a novel form of “holy island” under a Christian guise. Our conceptualization of the archaeological and other evidence in deep-time perspective is something of a response to Gilchrist’s call to engage more meaningfully with the sacred, particularly in how we have envisaged the actions and motivations of the later Medieval monastery. The material evidence generates a fresh insight, beyond textual sources, of how the Anglo-Norman abbey manipulated recognized holy sites to create and sustain institutional memories of legitimizing and sacralizing figures, while simultaneously ensuring that these same sacred places—away from the newly central claustral complex—were perceived as secondary in their new hierarchy of sanctity. By promoting Anchor Church Field as “Pega’s cell,” Crowland Abbey concurrently promoted their own claustral complex as the indisputable site of Guthlac’s hermitage and premier focus of pilgrimage, fixing once-mobile saints firmly into specific places in the landscape.

There is clearly much further work to be done on these themes, but we hope this paper encourages greater, Europe-wide innovation in the archaeology of monastic dependencies; it is clear that the places commonly labelled somewhat inconsistently as “granges” and viewed as relatively late establishments often have deep and rich biographies of their own, the understanding of which can only be fully revealed by prioritizing archaeological evidence in schemes of future research.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are expressed to John and Mark Beeken and their family, who supported our work throughout. We are also hugely thankful to Matthew and Helen Alcock and all the staff at Crowland Caravans and Camping, the generosity of whom made the project possible. Thanks are offered to John Blair, Michael Chisholm, Mark Gardiner, Sue Greaney, Martin Huggon, Edward Impey, Avril Lumley Prior, Michael Shapland, and Sam Turner for sharing their thoughts on the interpretation of the site and suggesting useful comparators. David Stocker generously provided his expertise in identifying and dating the worked stone and suggested parallels for the chapel. We are also grateful to Steve Ashby for identifying the two bone combs. Both reviewers were constructive in their feedback, and their suggestions have undoubtedly improved the paper. Our final thanks goes to the teams of students and volunteers who worked in challenging early post-pandemic conditions on the excavation and whose effort is the reason we now understand the archaeology of Anchor Church Field more fully.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Duncan W. Wright

Duncan W. Wright (Ph.D. 2013, Exon) specializes in medieval settlement and landscape archaeology and has a particular interest in the articulation of elite power. Duncan has published widely on both sides of the “early-late” medieval divide and is an active field archaeologist with an extensive background in landscape survey and excavation. He is the Principal Investigator of the AHRC-funded research project Where Power Lies: the archaeology of transforming elite centres in the landscape of medieval England c.AD800-1200. Duncan is a Member of the Chartered Institute of Archaeologists, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, and Deputy Editor of Medieval Archaeology. Orcid: 0000-0002-1793-7428

Hugh Willmott

Hugh Willmott (Ph.D. 1999, Dunelm) has research interests in the medieval and early modern periods in Europe and the archaeology of monasticism in particular. He has published on diverse topics such as glassmaking, dining, early ecclesiastical settlements, and the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In the past, Hugh has served on the committees of The Finds Research Group, the Society for Post-Medieval Archaeology, and The Royal Archaeological Institute. He is currently the chair of the Society for Church Archaeology and the archaeological advisor to the Diocese of Sheffield. He was elected a full member of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists in 2002 and a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2005. In 2017, Hugh was featured as one of the University of Sheffield’s Inspirational Academics. Orcid: 0000-0002-7945-7796

References

- Alexander, J. 2020. “Crowland Abbey Church and St Guthlac.” In Guthlac: Crowland’s Saint, edited by J. Roberts, and A. Thacker, 298–315. Donington: Shaun Tyas.

- Ashby, S. 2006. “Time, Trade, and Identity: Bone and Antler Combs in Northern Britain, c.AD700-1400.” York: Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of York.

- Blair, J. 2005. The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blinkhorn, P. 2022. “Pottery from Crowland, Lincolnshire (Site CROW21).” Unpublished Archive Report.

- Blinkhorn, P. 2023. “Pottery from Crowland, Lincolnshire (Site CROW22).” Unpublished Archive Report.

- Bradley, R. 1987. “Time Regained: The Creation of Continuity.” Journal of the British Archaeological Association 140 (1): 1–17.

- Bradley, R. 1993. Altering the Earth. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph 8. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- Brady, L. 2018. “Crowland Abbey as Anglo-Saxon Sanctuary in the Pseudo-Ingulf Chronicle.” Traditio 73: 19–42.

- Brink, S. 2001. “Mythologizing Landscape: Place and Space of Cult and Myth.” In Kontinuitäten und Brüche in der Religionsgeschichte, edited by M. Stausberg, 76–112. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter.

- Broadley, R. 2020. The Glass Vessels of Anglo-Saxon England c. AD 650-1100. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Browett, R. 2016. “The Fate of Anglo-Saxon Saints After the Norman Conquest of England: St Æthelwold of Winchester as a Case Study.” History 101 (345): 183–200.

- Carver, M. 2009. “Early Scottish Monasteries and Prehistory: A Preliminary Dialogue.” The Scottish Historical Review 88: 332–351.

- Chave, I. 2005. “Des sources comptables au service de l’archéologie: essai de reconstruction documentaire de la chapelle dite Saint-Nicolas du château de Falaise (Calvados), XIIe-XVe siècles.” Tabularia: Sources écrites des mondes normands médiévaux 2005. https://journals.openedition.org/tabularia/1219.

- Chibnall, M. 1987. Anglo-Norman England 1066-1166. New York: Basil Blackwell.

- Colgrave, B. 1956. Felix’s Life of St Guthlac. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Comeau, R. 2016. “Feeding the Body and Claiming the Spirit(s): Early Christian Landscapes in West Wales.” In Making Christian Landscapes in Atlantic Europe: Conversion and Consolidation in the Early Middle Ages, edited by TÓ Carragáin, and S. Turner, 205–224. Cork: Cork University Press.

- Cope-Faulkner, P. 2004. “Assessment of the Archaeological Remains at Anchor Church Field, Crowland, Lincolnshire.” Unpublished Archaeological Project Services Report No. 173/04.

- Cubitt, C. 2000. “Memory and Narrative in the Cult of Early Anglo-Saxon Saints.” In The Uses of the Past in the Early Middle Ages, edited by Y. Hen, and M. Innes, 29–66. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Decaëns, J., A. Dubois, and M. Allainguillaume2010. Caen Castle: A Ten Centuries’ Old Fortress Within the Town. Caen: Publications du CRAHM.

- Everson, P., and D. Stocker. 2011. Custodians of Continuity? The Premonstratensian Abbey at Barlings and the Landscape of Ritual. Lincolnshire Archaeology and Heritage Report Series No 11. Sleaford: Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire.

- Everson, P., and D. Stocker. 2023a. “Guthlac at Medeshamstede?” Early Medieval Europe 31 (2): 194–219.

- Everson, P., and D. Stocker. 2023b. Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, Volume XIV: Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire. Oxford and New York: The British Academy.

- Evison, V. 2009. “Glass Vessels.” In Life and Economy at Early Medieval Flixborough c. AD 600–1000. The Artefact Evidence. Excavations at Flixborough Volume 2, edited by D. Evans, and C. Loveluck, 103–112. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Evison, V. 2014. “Glass Vessels.” In Staunch Meadow, Brandon, Suffolk: A High-Status Middle Saxon Settlement on the Fen Edge, edited by A. Tester, S. Anderson, I. Riddler and R. Carr, 170–177. East Anglian Archaeology Report 151. Bury St. Edmunds: Suffolk County Council.

- Finucane, R. C. 1977. Miracles and Pilgrims: Popular Beliefs in Medieval England. London: JM Dent.

- Gilchrist, R. 2020. Sacred Heritage: Monastic Archaeology, Identities, Beliefs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gittos, H. 2013. Liturgy, Architecture, and Sacred Places in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gough, R. 1783. The History and Antiquities of Croyland-Abbey, in the County of Lincoln. London: Society of Antiquaries of London.

- Grenville, J. 1997. Medieval Housing. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Gresley, J. M. 1856. Some Account of Croyland Abbey, Lincolnshire. Ashby de la Zouche: W. & J. Hextall.

- Hall, D. 1987. The Fenland Project, Number 2: Fenland Landscapes and Settlement Between Peterborough and March, East Anglian Archaeology Report 35. Cambridge Archaeological Committee: Cambridge.

- Hall, A. 2007. “Constructing Anglo-Saxon Sanctity: Tradition, Innovation and Saint Guthlac.” In Images of Medieval Sanctity: Essays in Honour of Gary Dickson, edited by D. H. Strickland, 207–235. Leiden: Brill.

- Hall, D., and J. Coles. 1994. Fenland Survey: An Essay in Landscape and Persistence. London: English Heritage.

- Harris, R., and E. Impey. 2002. “Boothby Pagnell Revisited.” In The Seigneurial Residence in Western Europe AD c800-1600, edited by G. Meirion-Jones, E. Impey, and M. Jones, 246–269. BAR International Series 1088. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Hart, C. R. 1994. “The Foundation of Ramsey Abbey.” Revue Bénédictine 104 (3-4): 295–327.

- Hayes, P. P., and T. W. Lane. 1992. The Fenland Project Number 5: Lincolnshire Survey. Sleaford: Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire.

- Heale, M. 2004. The Dependent Priories of Medieval English Monasteries. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.

- Heslop, T. A. 2000. “Weeting ‘Castle’, A Twelfth-Century Hall House in Norfolk.” Architectural History 43: 42–57.

- Higham, N. J. 2005. “Guthlac's Vita, Mercia and East Anglia in the First Half of the Eighth Century.” In Æthelbald and Offa: Two Eighth-Century Kings of Mercia. Papers from a Conference Held in Manchester in 2000, edited by D. Hill and M. Worthington, 85–90. British Archaeological Reports, British Series 383. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Hill, N., and M. Gardiner. 2018a. “The English Medieval First-Floor Hall: Part 1 – Scolland’s Hall, Richmond, North Yorkshire.” The Archaeological Journal 175 (1): 157–183.