?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice, Poland is a complex of former prisoner of war (PoW) and resettlement camps that operated near the village from the time of the Prussian-French War (1870–1871) through the First and Second World Wars, including the interwar period, until the liquidation of the labor camp established by the Polish communist authorities in 1945–1946. Since June 2022, The Central Museum of Prisoners of War has been carrying out a project, a key part of which is the integration of various archaeological research methods for mapping the material remains of the camps that have been preserved until the present day in the local, mostly forested, landscape. Among the most important research problems was the issue of unknown and unmarked PoW burial sites and mass graves. The applied research methodology allowed, among other things, the locating of 60 structures, which can currently be interpreted as the quarters of Italian PoWs interned in Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf at the end of the Second World War. The excavations ended with the identification by name of the first two Italian soldiers.

Introduction

The Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice, Poland is a unique place on the map of Poland and Europe (Uryga Citation1982; Nowak Citation2006a; Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2017) (). The surrounding areas were part of subsequent PoW and resettlement camps associated with key events in European and world history. The first PoW camp in Lamsdorf was established because of the need to isolate approximately 6000 French soldiers taken prisoner in military actions during the Prussian-French War (Kisielewicz and Niestrój Citation2006). Then, during the Great War, one of the largest Prussian camps was established near the village. Approximately 90,000 soldiers of the Entente countries passed through its gates (Ciasnocha and Dzionek Citation2006). In the interwar period, the former camp infrastructure served as a resettlement camp for Germans (Pawlik and Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2006). Similarly, in the years 1939–1945, the surrounding areas formed one of the largest German PoW complexes, accommodating up to 300,000 PoWs of various armies who were detained here (Sawczuk and Senft Citation2006). The epilogue of the captivity in Lamsdorf (from then on, properly, Łambinowice) concerns the years 1945–1946, when the Polish communist authorities used part of the military training ground infrastructure as a labor camp (Nowak Citation2006b). In subsequent periods, when the areas were neither PoW nor resettlement camps, the landscape was used as a military training ground, the last one closing only in 2002. Due to the long and complex history of imprisonment in Lamsdorf, a separate institution was established in 1965, the aim of which was to conserve and maintain material traces, as well as preserve the memory of the place and people held in Lamsdorf. Currently, the institution is called the Central Museum of Prisoners of War (Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2017).

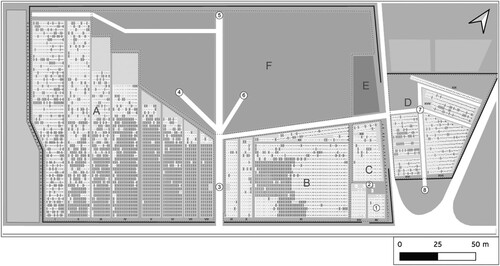

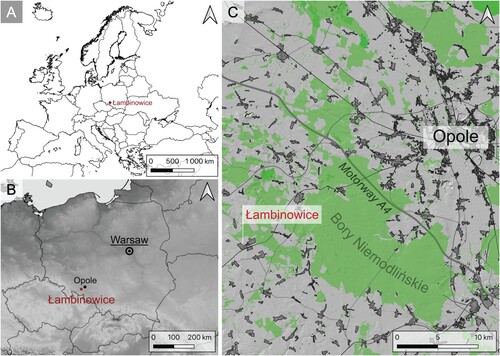

Figure 1. Location of Łambinowice in A) the map of Europe, B) Poland, and C) local area (prepared by K. Karski).

The Museum is responsible for taking care and managing part of the former PoW complex, transformed today into the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice (Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2017). It conducts various educational, social, conservation, and scientific activities. One of its latest initiatives is the multidisciplinary scientific project entitled “Science for society, society for science at the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice.” In short, it concerns three elements regarding the use of research methods and perspectives characteristic of three disciplines, namely history, ethnography, and archaeology. The use and integration of various sources were intended to allow mapping material remains related to the PoW and resettlement camps that operated in Lamsdorf in various historical periods. They were also expected to facilitate an analysis of the role and importance of this place for the present-day inhabitants of Łambinowice and its environs. Thus, following other similar research projects (e.g. Thomas Citation2019), the past (material traces of the camp) and its significance in the present day were thoroughly examined (e.g. Banaszek and Wosińska Citation2011; Saunders Citation2012; Morsch Citation2016; Pollock and Bernbeck Citation2016). The preliminary results of the research have already been published in both professional and popular science journals (e.g. Kobiałka et al. Citation2023a, Citation2023b, Citation2023c, Citation2023d).

The research was conducted in the spirit of “camp archaeology”—a subdiscipline of archaeological research whose subject refers to various types of former camps: PoW camps, labor camps, resettlement camps, concentration camps, and ending with “death factories” (German death camps established during the Second World War) (see Kola Citation2000; Gilead, Haimi, and Mazurek Citation2009; Moshenska and Myers Citation2011; Bem and Mazurek Citation2012; Sturdy Colls Citation2015; Bernbeck Citation2018; Jasiński Citation2018), to mention but a few. The territory of contemporary Poland was affected and maimed in a multidimensional way as a result of the First and Second World Wars, the Cold War leaving its material imprint, as well (e.g. Kobiałka, Kajda, and Frąckowiak Citation2015; Kiarszys Citation2019). The legacy of those events includes various types of camps which have been the subject of historical research for decades. Although the first archaeological research on the site of Auschwitz-Birkenau was carried out in the 1960s, it is only in recent years that archaeologists have become genuinely interested in this issue (Karski and Kobiałka Citation2021).

It should also be clearly noted that the first archaeological work consisted primarily of invasive research. Today, following the development of similar research in Europe and around the world, excavations in the areas of former camps are only the climax of a complex research program. It usually includes three elements: 1) the stage of desk-based research, 2) the stage of non-invasive archaeological research, and 3) test excavation (e.g. Sturdy Colls Citation2015; Karski Citation2020). This research methodology was used when researching the PoW camps in Czersk and Tuchola from the time of the Great War (Kobiałka Citation2018, Citation2022; Kostyrko and Kobiałka Citation2020), the labor camp near Gutowiec, functioning during the Second World War (Kobiałka Citation2017), or, likewise, KL Plaszow camp (Karski and Kobiałka Citation2021), to mention but a few.

For the purpose of the project, it was hypothesized that even in the case of such a well-researched topic as the history of captivity in Lamsdorf, the use of archaeological methods and sources and their integration with historical, ethnographic, and other data may result in obtaining new findings (Nowak Citation2006a). Indeed, analyses of remote sensing data allowed mapping several thousand material traces in the local landscape related to the PoW camps and the history of the former military training grounds. Systematic metal detector surveys resulted in the discovery of more than 600 objects or their fragments related to the history of the place. Similarly, the excavations made it possible to draw documentation of the remains of the PoW barracks. All this has revealed the diversity of the camp’s material heritage related to the history of imprisonment and internment in Lamsdorf (Kobiałka et al. Citation2023a, Citation2023b, Citation2023c, Citation2023d).

This paper focuses on the problem of missing graves of PoWs who died in Lamsdorf during the Second World War, as they constitute one of the most important kinds of material heritage related to the history of the site. The following parts of the text present the historical and research contexts of the undertaken work. Then, the selection of methods used and collected data, which led to a partially positive verification of one of the research hypotheses, is discussed. In 2023, thanks to the applied research methodology, it was possible to reveal unknown and unmarked quarters of graves of Italian soldiers detained in Lamsdorf at the end of the Second World War. Importantly, the excavations carried out allowed the confirmation of the functions of the discovered place and the establishment of the identity of two soldiers buried in the graves.

Historical and Research Contexts

One of the most important and unresolved problems regarding the history of the PoW camps in Lamsdorf is the location of the graves of Polish, French, Greek, Italian, and American PoWs who were buried either in the so-called Old PoW Cemetery in Łambinowice or in the vicinity of the German PoW camps operating in this area (Więcek Citation1969; Uryga Citation1978; Rezler-Wasielewska Citation1995, Citation2000; Wickiewicz Citation2016; Michalski and Różycki Citation2021). Importantly, the issue also concerns Soviet and British soldiers, whose burial sites were examined, commemorated, and/or exhumed after the end of the Second World. In this case, there are significant source gaps regarding both the number of buried prisoners and their resting places, as well as the answer to the question of what has happened to the known locations of mass graves and individual burial places over the decades since the end of the Second World War.

About 300,000 PoWs of various military affiliations passed through the complex of German PoW camps located in Lamsdorf (after the end of the Second World War, the name of the place was changed to Łambinowice, the village located in Nysa County in Opole Voivodeship) between the years 1939 and 1945. The largest group was Red Army soldiers, whose number is estimated at almost 200,000. In their case, according to research conducted so far, they suffered the highest losses as regards the number of victims, which is around 40,000 PoWs buried anonymously in the vicinity of both Lamsdorf stalags. However, only one place was commemorated and established as a cemetery after the war (Rezler-Wasielewska Citation1995, Citation2000). The monument located near the area of Stalag 318/VIII F (344) Lamsdorf, where they were accommodated, was placed in the central area of the hill, the largest concentration of mass graves in which Soviet soldiers were buried. Two other locations of mass graves near the area of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf and the cemetery known today as the Old PoW Cemetery, which were not invested with a commemorative character, are the subject of inquiries, including whether all the graves or the remains of the PoWs have been found. The preserved research reports of Soviet and Polish teams from 1945 and 1946 do not provide clear answers to any of the above questions (Archive Citation1, signature 95; Łukowski Citation1965; Popielski Citation1984).

In the case of the documented interment of British PoWs, known by name and surname, buried in the Old PoW Cemetery in single graves, there are also some issues which have not been fully explained. After the end of hostilities, as part of a nationwide exhumation campaign coordinated by the British Embassy, the bodies of 143 deceased Britons were transferred from this cemetery to the Rakowicki Cemetery in Kraków (Rezler-Wasielewska Citation1995, Citation1998, Citation2000). It should be noted that, according to British documentation—prepared on an ongoing basis during the war—at least 159 PoWs of the British Commonwealth and PoWs belonging to other armies of the anti-Nazi coalition were buried in the cemetery (Archive Citation2; Wickiewicz Citation2016). Other sources available in Russian archives mention the death in the period from June 1941–January 1945—apart from Soviet PoWs—of 245 Britons, 9 Poles, and 83 prisoners of other, but unspecified, nationalities without indicating the place of burial (Nowak Citation1993). Therefore, it is probable that the data also concern the mortality rate of PoWs in labor commandos outside the main camp.

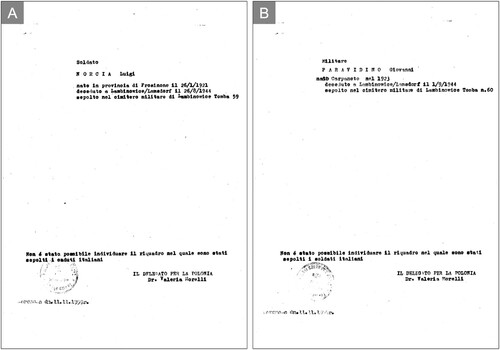

Among the available information on the mortality of PoWs and their places of interment, the most noteworthy piece concerns Italian soldiers who, as a consequence of the political and military changes implemented by the Italian government during the Second World War, were interned as Italian Military Internees, IMI (Senft Citation2000), beginning in September 1943 in Lamsdorf, among other places. In 1959, acting upon a prior agreement with the Polish government, an Italian government commission stayed in Łambinowice and searched for at least 60 graves of their compatriots who had refused to further cooperate with the German government of the Third Reich. According to the available information, the graves should be located in the Old PoW Cemetery (Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2000) (). The activities of the Italian commission, despite its members having a list of the buried, did not bring positive results as regards finding the burial places: “[…] The District Branch of the Polish Red Cross in Niemodlin kindly informs that according to the attached list, no Italian graves have been found and it is simply impossible to find [them] according to the list. The cemetery is in the forest and was unattended in the post-war years. People from nearby villages grazed cattle there. The crosses on the graves were temporarily made of wood, with numbers and names visible on them, currently there is no trace of the crosses […] or graves. Some graves are visible here and there, most of them overgrown with trees […]” (Archive Citation3, signature LS 59228; authors’ translation).

Figure 2. Documentation concerning burials of Italian soldiers in the PoW cemetery in Lamsdorf. A) Information concerning Luigi Norcia and B) information concerning Giovanni Paravidino (source: the Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

A similar situation occurs in the context of Polish PoWs held in Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf. To date, it has not been possible to determine the location of any such burial site, despite intensive historical research on this subject and archaeological work carried out in 2020 by the Search and Identification Office of the Institute of National Remembrance (Borkowski Citation2021). This applies to both individual burials, documented in German reports, and mass burials, appearing in the accounts of historical witnesses: “In October 1939, two German guards came to the tent and said that they needed volunteers for work. I then volunteered with other companions, there were about 30 of us in total. All the 30 of us were taken out under guard and about 300 meters from our camp, on a hill covered with acacia bushes, we were ordered to dig a hole. The hole we dug was about three meters wide and twenty meters long and two meters deep. We dug three holes and the digging took three days. On the day we were digging the third hole, around 3 p.m., I noticed that a group of prisoners in Polish uniforms, approximately 20 people, had been brought to the place located about 50 meters away from us. I saw the Germans order them to undress, the prisoners took off their uniforms and underwear. I couldn’t continue any further observations because the Germans who were supervising us ordered us to go down into the dugout hole, so I couldn’t see anything. While I was below, I heard a series of gunshots. After some time, when we were allowed to leave the pit, in the place where the Polish prisoners had been, I saw only Germans and Polish uniforms lying on the ground. I could also hear groans coming from that direction” (Sawczuk Citation1974, 76; authors’ translation). Wiktor Węgra also mentioned crimes committed against Polish PoWs: “I stayed in Łambinowice until August 1941. Starting in 1940, usually after the selection of prisoners, I heard machine gun bursts at the end of the camp, to the left of the entrance. At that time, there were small birch trees growing there. Once I was there and saw a mass grave, uncovered, in which I recognized sergeant Kowalski from Będzin […]. I saw several other corpses, covered in blood. There could be more than 20–25 people in that grave. I firmly state that those bodies had gunshot wounds, as bullet holes and exits were visible […]. And regardless of this, the bodies of the deceased prisoners of war were transported by car and transferred onto an ordinary cart, which in turn was how they were transported to the cemetery […]” (Archive Citation1, signature 6; authors’ translation).

The number of buried Polish PoWs, depending on the sources, ranges from several, several dozen, several hundred, and even up to several thousand people (Archive Citation1; Archive Citation3; Archive Citation4; Sawczuk Citation1974; Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2000; Stanek Citation2017). Apart from the number of deceased and/or killed PoWs and internees, another challenge relates to the location of their potential graves. Archival materials are ambiguous in this regard and differ from each other (Archive Citation1, signature 6, 61). Crucially, despite the relatively few original German documents from the period of operation of the Lamsdorf PoW camps and the post-war accounts of PoWs who survived captivity in Lamsdorf, it can be safely concluded that the surrounding areas must hide unknown and unmarked burials from the period of the Second World War. The archival materials indicate that the surrounding forests may hide unmarked graves and that there should be unmarked contemporary burial sites connected with the functioning of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf in the area of the Old PoW Cemetery in Łambinowice (Michalski and Różycki Citation2021; Michalski Citation2022, Citation2023).

The above conclusion was the basis for conducting archaeological research as part of the project “Science for society, society for science at the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice,” one of the goals of which was to try to find the “missing” burial sites of PoWs ().

Archaeological Methods and Data

The lack of German sources cannot prevent conducting research aimed at indicating and clarifying doubts related to the burials of PoWs of various nationalities who died in Lamsdorf during the Second World War. Documents in the form of PoW registers, reports, and aerial photos taken by both the Allied troops and the Germans may constitute the basis for research related to the search for unknown interment places of soldiers of the anti-Nazi coalition who were buried in Lamsdorf (Michalski and Różycki Citation2021). This type of documentation is among the key ones in the context of reconstructing the campscape (e.g. Doyle, Pringle, and Babits Citation2013; Kuryłowicz, Koziak, and Kozioł Citation2017; Tucholski Citation2019; Sturdy Colls, Kerti, and Colls Citation2020; Michalski and Różycki Citation2021), as well as the location of unknown PoW graves (e.g. Godziemba-Maliszewski Citation1995; Dukaczewski et al. Citation2017; Ossowski et al. Citation2018; Čičiurkaitė Citation2022).

During the Second World War, both the Allied Forces and German aviation intelligence took an incalculable number of photos capturing various aspects of the war. Currently, only one of the archives, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), has preserved and made available to researchers a collection of the Allies’ and German aerial photos from the 1939–1945 period, the number of which, only as far as the preserved German photos are concerned, amounts approximately to 1.2 million documents (https://www.archives.gov/research/cartographic/aerial-photography/foreign-photography?fbclid=IwAR2kdU9g4bjLvDtNugy2eVJUqDZR4g1KwNfM0H3CIrkjFwnmUJYY0ZmKXWQ, accessed 1.12.2023).

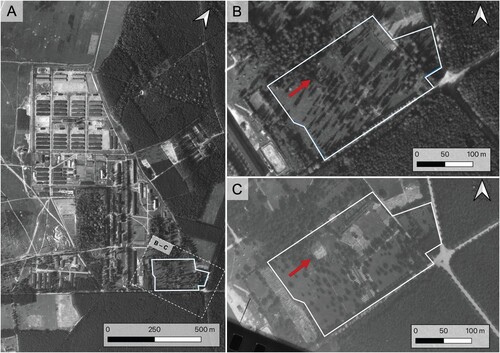

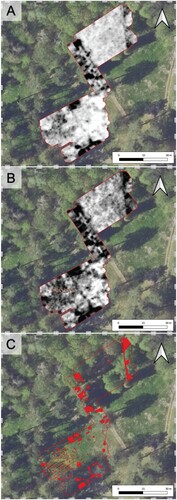

As part of the search for historical materials in the form of aerial photos for the area of the Lamsdorf camp complex, several aerial photos covering the area of interest were selected and obtained in the first phase from the resources of the NARA, the Bundesarchiv, and the Herder Institute (). Unfortunately, the aerial photos taken on September 15 and 30, 1944, as well as on October 16, 1944, did not bring any decisive results in indicating the location of the graves (). However, they revealed anomalies that could not be clearly interpreted due to their small scale and relatively poor quality. Preliminary findings made it possible to indicate the location of the observed anomalies, though.

Figure 5. Campscape of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf. A) A general view of the camp in October 1944 with location of the camp cemetery marked; B) a fragment of a photo taken in October 1944 documenting the camp cemetery—the arrow indicates the Italian quarters; and, C) a fragment of a photo from July 1944 documenting the camp cemetery—the arrow indicates the Italian quarters. Based on vegetation marks and their number and the date of the photo, it was assumed that the registered place was the quarters of the Italian soldiers who died at the end of the Second World War in Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf (prepared by K. Karski; source: The National Archives and Records Administration).

Table 1. Photos obtained and analyzed for the purpose of the project (prepared by M. Michalski).

Further inquiries into the unknown burial places of Lamsdorf’s PoWs had important consequences. An aerial photo taken on July 26, 1944 was found and obtained, the quality of which indicated the location of one of the quarters of the PoWs buried in the Old PoW Cemetery in Łambinowice (see C). At a later stage, while analyzing archival materials, a comparison was made of the number of anomalies visible in the aerial photo in the form of darker marks, in a shape similar to a rectangle, in relation to the information regarding the dates of PoW burials. This procedure allowed us to put forward the research hypothesis that the visible anomalies in the form of vegetation marks may be the graves of the Italian PoWs. This was indicated primarily by the number of deaths recorded in the documents in relation to the number of visible anomalies at the time the aerial photo was taken. Additionally, this hypothesis was supported by the similarity of the observed anomalies to the graves of British PoWs also visible in the same aerial photo. Importantly, according to the list of buried Italians, which was used by the Italian commission during its visit in 1959, 54 or 55 PoWs had been buried in Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf before the day the aerial photo was taken (see Rezler-Wasielewska Citation2000). Interestingly, the same number of vegetation marks was found in the aerial photo of July 26, 1944.

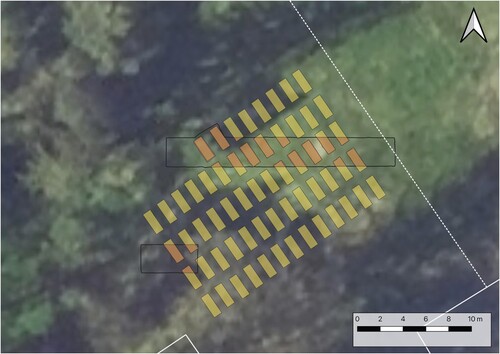

The photo of July 26, 1944, presently in the NARA collection, became the subject of further analyses and processing. It was georeferenced in QGIS free software, thus inserting the relevant marks in the contemporary landscape of the Old PoW Cemetery in Łambinowice. The initial interpretation of vegetation marks and their range were the basis for selecting the area for geophysical research. Due to the specificity of the site and the examined remains (single graves), the Ground Penetrating Radar method (GPR) was chosen and used accordingly (see also Fernández-Álvarez et al. Citation2016; Freund Citation2019).

Subsequently, in the pursuit of verifying the archival aerial imagery findings, which indicated traces of soil disturbances potentially linked to a clandestine burial site, a comprehensive GPR survey was conducted. Utilizing a single-antenna 400 MHz system, the survey aimed to map the subsurface features with high horizontal and vertical resolution. The choice of a 400 MHz frequency was strategic, balancing penetration depth with resolution. The survey’s execution involved a systematic approach, maintaining an average profile spacing of 0.75 m and the use of a RTK GPS for geolocation.

The GPR survey encompassed a total of 3100 m2 of measurements, spread across 95 profiles. This extensive coverage was instrumental in creating a comprehensive subsurface map of the area. The data, characterized by high-resolution reflections, was subjected to post-processing and analysis. The interpretation of these data involved mapping the GPR reflections both on profiles and digitally derived time-slice plans in order to locate areas characteristic of anthropogenic soil interference.

The high-resolution measurements from the GPR survey significantly supported the hypothesis derived from the aerial imagery analysis, adding a new layer of understanding to the spatial arrangement and extent of the historical cemetery site. The surveyed area, supposedly containing clandestine graves, was characterized by distinct, shallow subsurface anomalies. These were identified through detailed analysis of GPR time-slice images, which revealed irregular patterns of reflectance in the topsoil. The irregularities suggest varied degrees of soil disturbance, indicative of historical human activity at shallow depths. The anomalies, presented in , align with the expected locations of graves and provide quantifiable evidence of non-uniform topsoil disruption.

Figure 6. Interpretation of the results of GPR survey in the PoW cemetery in Łambinowice. A) GPR survey time slice grayscale visualization (0–50 cm); B) contrast enhanced visualization with superimposed plan of graves located through excavation; and, C) mapping of shallow GPR anomalies with superimposed plan of graves located through excavation (prepared by P. Wroniecki; source: The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

Results

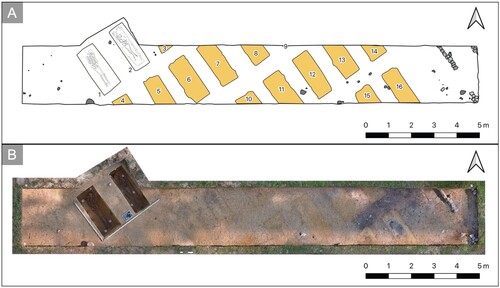

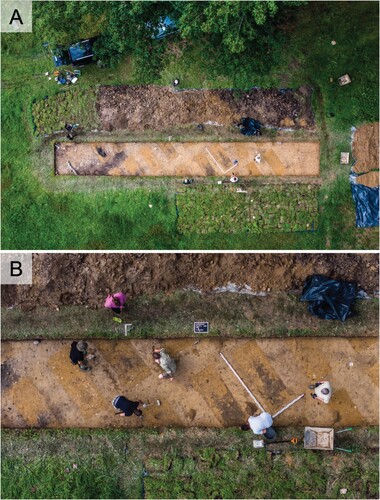

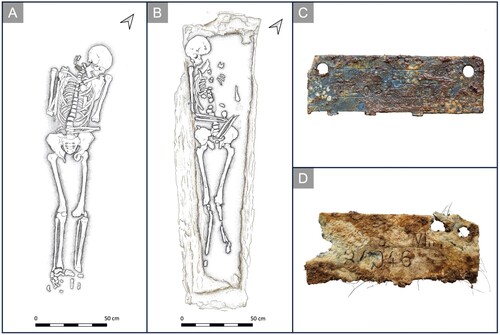

The archaeological excavations conducted in 2023 at the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice included work in the Old PoW Cemetery with the aim to prove the hypothesis of identified quarters of Italian PoWs. All in all, two test trenches were opened (numbered 5/2023 and 6/2023). They were located in the western part of sector F, in the area at the height of sections V–VII, near the obelisk dating from the time of the Great War commemorating the British PoWs who died in Lamsdorf (see ).

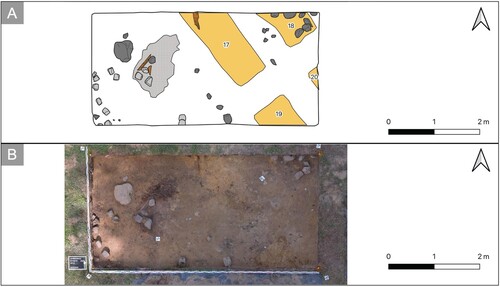

The locations of the excavations were chosen on the basis of a preliminary analysis of aerial photos taken in July 1944. Trenches 5/2023 and 6/2023 were located in accordance with geographical directions (). During the exploration of the 5/2023 trench, a small, segmental enlargement was made to include the first two isolated structures. In both cases, after removing the topsoil layer, it was possible to separate the top parts of regular structures similar in shape to elongated rectangles with average dimensions of 80 × 200 cm. They were arranged in a regular grid—at least four rows and eight columns (5/2023) and two rows and two columns (6/2023)—while maintaining approximately regular spacing between the boundaries of the structures (approximately 65–80 cm). In all cases, the fill of the structures was clearly separated from the natural ground—yellow, loamy sand with light grey-yellow interlayers. In the eastern part of trench 5/2023, a darker layer, dark grey in color, with a slightly coarser fraction was documented. However, in trench 6/2023, there were interlayers of the topsoil ().

Figure 7. General plan of excavations carried out in 2023 at the PoW cemetery in Łambinowice. A) Plan of the cemetery divided into individual sectors marking the place of excavations on the orthophoto map (prepared by K. Karski and A. Lokś); B) plan of the cemetery divided into individual sectors marking the place of excavations on the airborne laser scanning visualization; and, C) location of the trenches on the orthophoto map (source: Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography, Poland, The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

Figure 8. Trench no. 5/2023. A) Interpretation of the results and B) orthophoto map (prepared by K. Karski and A. Lokś; source: The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

Figure 9. Trench no 6/2023. A) Interpretation of the results and B) orthophoto map (prepared by K. Karski and A. Lokś; source: The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

In most cases, at the stage of separating the structures, slight deepening of the topsoil could be observed, resulting from the natural settling of the pit fill and interlayering of the topsoil. The actual fills were mostly homogeneous deposits of yellow clay sand with light, almost white precipitates. The only architectural remains recorded were the remains of the cemetery path framing in trench 5/2023. This was made of small, roughly hewn granite cube-shaped stones, similar to the existing cemetery paths. Similar stones were documented in the western part of trench 6/2023.

A total of 20 archaeological structures were identified: 16 in trench 5/2023 and four in trench 6/2023. They were given consecutive numbers from 1–20. Two of them were examined, confirming their earlier identification as graves. During the field research, it was alleged that they were unmarked graves. The results of the conducted research allowed us to confirm this hypothesis. Only two structures were explored (graves no. 1 and 2), but the observations made it possible to determine the functions of the remaining ones ().

Figure 10. An example of documentation of field research—trench no. 5/2023 (author D. Frymark; source: the Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

Grave no. 1

Within the burial pit, the remains of one individual were found, placed in anatomical order. The overall preservation of the bones was good. The deceased was lying on his back (A). The axial skeleton was completely preserved—the skull was slightly tilted relative to the axis of the spine, with the viscerocranium tilted to the left and the maxillae and mandibula placed over the left clavicle. The ribs were complete, with few cases of sternal end damage. The whole spine was well preserved.

Figure 11. Documentation of A) burial site no. 1 and B) burial site no. 2 and photographs of PoWs’ tags: C) the one found in grave no. 1—number 1064, belonging to Giovanni Paravidono and D) the one found in grave no. 2—number 84086, belonging to Luigi Norcia (prepared by K. Karski, Rewers, and D. Frymark; source: The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

The peripheral skeleton was completely preserved except for the bones of the hands, feet, and the right scapula, which were damaged postmortem. The upper limbs were placed along the body. The humerae were located directly along the chest with the right forearm parallel to the humerus (bent at the elbow joint) and the bones of the hand at the level of the neurocranium. The left forearm was positioned on the stomach, with the hand bones located near the right hip bone. The long bones of both lower limbs were placed parallel to the body axis. The documented tarsal and metatarsal bones suggest an outward position of the feet with the calcaneus pointing inward relative to the body axis and the metatarsal bones pointing sideways.

During the exploration, only one artifact was found: half of the PoW identification mark, which was located on the right side of the cervical spine. It is a small metal plate. Its state of preservation should be marked as average—most of its surface is covered with corrosion products and pits. In two lines, between the rows, the following inscription was stamped (C):

The discovered identity mark—a dog tag—was created according to a schematic pattern: a small elongated metal plate with three holes punched in the corners and divided horizontally into two halves: the name of the camp, in accordance with the all-German classification, and the PoW number stamped in a mirror image in two lines. In the event of a person’s death, the dog tag was broken. The part with two holes was left next to the body, while the other part was taken away to record the death.

Grave no. 2

The burial pit was noticed immediately after the exposure of one mechanical layer below humus approximately 20 cm thick. In order to record the entire outline of the burial pit, it was necessary to slightly widen the trench. In horizontal projection, the pit appeared as an elongated rectangle stretching along the axis of the cemetery plots north-northeast/south-southwest. At the time of documentation, it had dimensions of approximately 205 × 88 cm. In the bottom part, there was a partially preserved coffin (without a lid). Further exploration was carried out within it.

Documentation and descriptions were prepared after each layer (20–25 cm) had been removed. Due to the impossibility of separating additional layers within the pit, their separate recording was not carried out. After removing the top interlayers, the fill looked homogeneous and sandy, with a fine, dark yellow clay fraction. The remains were recorded at a depth of approximately 130 cm. Within the burial pit, the remains of one individual were found in anatomical order. They were placed in a coffin without a preserved lid in the supine position. The general state of preservation was poor and fragmented, but there was a clear discrepancy in the degree of preservation between the left and right sides of the upper body, with the left side exhibiting pronounced incompleteness and fragmentation (B).

The axial skeleton was partially preserved. The skull was tilted relative to the axis of the spine and rested on the edge of the coffin with the viscerocranium tilted to the right. The mandible dropped noticeably towards the chest. Partial preservation of the left ribs was observed (comprising three rib fragments), while the right ribs were firmly compressed against the coffin’s edge. Similarly, the spinal column displayed partial preservation, marked by the absence of numerous thoracic vertebrae, with the extant bones displaying significant damage.

The peripheral skeleton was partially preserved. The upper limbs were placed next to the body with hands around the pelvis (single metacarpals and phalanges). The left humerus was absent, the right humerus was located directly next to the body, and the forearm bones were located on the stomach and pelvic area. The long bones of both lower limbs were arranged parallel along the body axis. The tibiae, fibulae, and feet bones were poorly preserved and incomplete. During the exploration, two items were found. The first one was a nail that was located at the bottom of the coffin. The second one was half of the PoW’s identity mark. Its location was determined only after using a small metal detector, as it was found under the cervical vertebrae, pressed into one of the vertebral bodies. The form and the size of the dog tag were similar to that found in grave no. 1, but its state of preservation made it impossible to initially decipher the inscription. The entire surface was covered with extensive corrosion products, and the tag itself appeared brittle. In order to ensure stable physical and chemical conditions for the object, immediately after its extraction, it was tightly packed, together with a small amount of soil from the grave fill, and transferred to the warehouse of the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in order to compensate for significant changes in temperature and humidity, and then transferred for immediate conservation. Conservation work revealed the following number stamped on the plate (D): 84046.

Discussion

The stratigraphy of the pits documented during the field research can be interpreted as contemporaneous, undisturbed by subsequent interference. Previous analyses of iconography allowed us to determine that section F of the Old PoW Cemetery in the interwar period was not part of the necropolis. The reason for this state of affairs was most likely the exhumations carried out in the 1920s, which significantly reduced the number of burials in the cemetery, and the empty part was most likely fenced off and incorporated into the military training ground (Michalski and Różycki Citation2021; Michalski Citation2022). Therefore, the discovered graves should be associated with the period of the Second World War.

The time of the creation of the paths within trench 5/2023 remains undetermined. It is considered probable that they were built during the time when the necropolis was in use during the Great War. The interpretation regarding the chronology of the graves is directly confirmed by the discoveries of grave equipment. In both cases, characteristic identification marks belonging to PoWs in stalags were discovered. According to the procedure, both were broken—one part with information about the camp number was placed in the grave, most likely hung on a string around the neck. In one case (grave no. 1), the condition of the PoW identity tag allowed us to read the recorded information during the excavation. The PoW identity tag belonged to PoW no. 1064 from Stalag VIII B Lamsdorf: Giovanni Paravidino. Some of the basic and most important information concerning the PoW has already been determined. Giovanni Paravidiano was born on June 25, 1923 in Carpaneto Piacentino (Piacenza, Emilia-Romagna). He was a soldier of the 1st Alpine Regiment. On September 9, 1943, he was interned in Bologna and sent to Stalag I A Stablack (commonly referred to as the camp in Kamińsk or the camp in Stabławki); he was assigned number 1064. Then, he was transferred to Stalag VIII B Lamsdorf (Łambinowice), where he died on September 1, 1944.

The other identity mark did not initially reveal the personal details of the deceased. However, conservation work allowed us to decipher the number as 84046. The preserved Red Cross documentation proves that this number was assigned to Luigi Norcia. Again, like in the previous case, some of the basic and most important information concerning the PoW has already been determined. Luigi Norcia was born on January 21, 1921 (some documents have the date of January 25, 1921) in Cassino (Frosinone, Laio). As a soldier of the 10th Infantry Regiment, he was interned on October 4, 1940 in Greece, on the island of Rhodes. From there, he went directly to the PoW camp in Lamsdorf—Stalag 318/Stalag VIIIB. He received PoW number 84046. He died on August 26, 1944.

Nonetheless, the scope of the discovered burial quarters remains undefined. Based on the current state of research, it can be assumed that it consisted of regular rows, at least four, of 13 burial sites each, with the northernmost fragment including eight graves. Importantly, the found and identified remains of Luigi Norcia and Giovanni Paravidino, close to the northern row of the plot were, according to the death list, the last two Italian soldiers who died in Stalag 318/VIII F (344) Lamsdorf and were buried. By finding their burial sites, the last graves of the Italian soldiers in Lamsdorf have been registered. Thus, knowing the location of the graves in the plot and the dates of their deaths, it should be possible in the near future to find and identify the remaining 58 Italians interned in Lamsdorf and buried in the local Old PoW Cemetery ().

Figure 12. Reconstruction of the Italian quarters in the PoW cemetery with marked burial pits (in orange), which were recorded during excavation carried out in 2023 (prepared by K. Karski; source: The Central Museum of Prisoners of War).

Finally, the discussion should also emphasize the ethical aspects of the presented project and field research, which were the key element. The issue of ethics is always a complex matter, especially in the sensitive context of searching for and exhuming the remains of victims of recent conflicts without the formal consent of relatives or relevant organizations. The same applies to the question of whether there is a sufficient scientific basis to conduct such activities for the benefit of science at all. The victims had close relatives—fathers, mothers, daughters, sons, etc. It is not obvious whether everyone always wants to find and recover the remains of their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents. There are no ready answers, and each case depends on the history of a given country or religious community (Sturdy Colls Citation2015).

Archaeologists increasingly regard their activities as a practice of social and cultural importance. These and many other pertinent issues have already been discussed in the literature (e.g. Desfossés, Jacques, and Prilaux Citation2008; Moshenska Citation2008; Steele Citation2008; Blau Citation2015; Newson and Young Citation2022), and these discussions have accompanied us throughout the stages of project preparation and subsequent implementation. As emphasized, one of our goals was to locate unknown and unmarked graves of prisoners and individuals interned in Lamsdorf during the Second World War. However, it was not to hastily exhume the discovered deceased. Our research proceeded as follows: after the discovery of human remains in graves no. 1 and 2, they were documented photographically, 3D models of the found remains were prepared, all necessary measurements were taken, and a preliminary physical anthropology analysis was carried out in situ. The only invasive actions concerning the deceased involved the removal of their broken dog tags.

In the case of grave no. 1, where the camp number could be read on-site, the hypothesis of finding Italians who died in Lamsdorf was confirmed. Work was immediately halted, and the Polish authorities, along with representatives of the Italian Republic, were promptly informed about the discovery. Both graves, along with trenches 5/2023 and 6/2023, were secured and restored to their original condition, because there was no chance for a quick decision. Ethical considerations guided our work. With the confirmed identity of the person from grave no. 1 (and, shortly after, the Italian from grave no. 2), the government of the Italian Republic and the families of Giovanni and Luigi should decide on the next steps. The same principle applies to the families of the remaining 58 Italians, whose names are known from archival materials. The Italian authorities have been attempting to contact them and discuss the situation.

Based on the information received from the Italian parties, it is known that the families of the two soldiers wish to bring their loved ones back to Italy for burial, on “their land and among their own people.” It can be assumed that a similar situation may arise with most, if not all, of the other families of the deceased PoWs. As these words are written, efforts are underway to organize archaeological research focused on the exhumation, using archaeological methods and techniques to document the Italians from all the discovered quarters. Our aim is for their families to have the opportunity to participate in this event, at least to some extent. Currently, efforts are being made to expand our scientific team to include colleagues from Italy. The story of Italians from Lamsdorf is, in fact, our shared heritage—primarily Italian, but also an integral part of the heritage and history of present-day Poland as a country.

It is also important to emphasize that, for ethical reasons, we intentionally excluded from the text high-quality photographic documentation of the remains of Giovanni and Luigi, as well as 3D models of their remains and archival photos obtained after the discovery. Using drawing as a form of documentation aligns with the scientific aspirations of field archaeology as we understand and practice it. This approach takes into account the ethical, social, and cultural contexts of our project activities.

Conclusion

The material heritage related to the PoW and resettlement camps in Lamsdorf is very complex and diverse. Its state of preservation also varies greatly—from the ruins of Stalag 318/VIII F (344) Lamsdorf, part of which is a fragment of the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice, to remains scattered over almost 300 ha of the surrounding forests and wastelands. The main goal of the project “Science for society, society for science at the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice” was to map their relics that have remained preserved to this day. The work undertaken was based on the hypothesis that despite the huge number of historical sources studied by historians over the following decades, the “archaeology of the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice” might contribute to new discoveries and findings. It was assumed that archaeology does not consider the past as it was but as what has remained materially from then to the present (González-Ruibal Citation2019). This is a seemingly small, yet fundamental, difference and value—broadly speaking—from the archaeological perspective.

Fieldwork carried out in 2022 and 2023 made it possible to register several thousand camp relics. Desk-based research and non-invasive archaeology consisting of analyzing remote sensing data (plans, historical and contemporary aerial photos, airborne laser scanning derivatives, metal detector surveys, GPR research, and photogrammetry) allowed us to discover the remains of PoW barracks, latrines, camp warehouses, roads and paths marking communication routes, anti-aircraft ditches, and even garbage pits, to list a few. The surrounding forests hide a huge variety of camp heritage which archaeology is able to identify and record.

Known and unknown graves—both individual and mass—constitute a special category of camp relics. Archival materials (primarily post-war testimonies of PoWs interned behind the barbed wire of Lamsdorf stalags in the years 1939–1945) revealed that only a small part of the PoW graves were marked. This mainly concerned British PoWs who were exhumed in the post-war period. From the same data and exhumation reports, it was known that mass graves of Soviet PoWs were located near the Old PoW Cemetery in Łambinowice and near Stalag 318/VIII F (344) Lamsdorf—their precise location and dimensions are currently unknown, as is the exact number of buried captives.

Here, it is important to remember that even the approximate number of Polish PoWs captured and detained in Lamsdorf since September 1939 is hardly precise. Some authors and witnesses claim that there are thousands of Poles who are “missing” and that it is still not known what actually happened to them (Stanek Citation2017). We should add to this number several thousand Home Army soldiers and civilians who were sent to Stalag 318/VIII F (344) Lamsdorf after the failure of the Warsaw Uprising. Some of them never passed the camp gates again, finding their premature deaths there and thus augmenting the final toll of the war victims. In many cases, it is not known where their corpses were hidden.

Finally, archival materials clearly identified a group of 60 Italian soldiers who died in Lamsdorf. The location of their graves has also remained unknown for decades now. Therefore, the adopted project methodology, designed to try to locate the remains of at least some of the missing PoWs, promises to fill in this void, since, thanks to the research methodology founded on desk-based research, non-invasive archaeology, and test excavations, it has been possible to locate the quarters of the Italian PoWs. The test excavations carried out in 2023 made it possible to determine the identity of the two soldiers whose skeletons were discovered in excavated graves. The families of the deceased soldiers have already been notified by the Italian government about the discoveries.

The conducted research clearly demonstrates its scientific, conservation-related, social, and cultural value, as well as humanitarian dimensions. The model used is to be implemented in the near future to reveal the entire quarter, to exhume the remains of the Italian soldiers, and to make efforts to hopefully find other missing PoWs. Families have been waiting too long for reliable information about what actually happened to their loved ones (fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandparents) and where exactly their graves are. It is evident that science and researchers’ dedication can help find answers to such questions in the spirit of projects investing science with the mission to serve society.

Acknowledgement

The project was co-financed from the state budget under the program of the Minister of Education and Science, Poland called “Science for Society,” number: NdS / 545193/2022/2022, amount of funding: PLN 560,740,00, total value: PLN 560,740,00.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dawid Kobiałka

Dawid Kobiałka (Ph.D. 2014, Adam Mickiewicz University) is an Associate Professor at Lodz University with a focus on forensic archaeology, contemporary archaeology, and heritage studies.

Marek Michalski

Marek Michalski (M.Eng. 1995, Silesian University of Technology) is an independent researcher involved in the interpretation of historical aerial photographs with a particular focus on research related to unknown sites of mass and individual graves of victims from the Second World War.

Kamil Karski

Kamil Karski (Ph.D. 2023, Jagiellonian University) is an archaeologist and collection manager at KL Plaszow Museum. His research is focused on the archaeology of the 20th century a.d. and museology studies.

Adam Lokś

Adam Lokś (M.A. 2018, Adam Mickiewicz University) is an independent researcher interested in remote sensing methods in archaeology, contemporary archaeology, and landscape studies.

Michał Pawleta

Michał Pawleta (Ph.D. 2005, Adam Mickiewicz University) is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Archaeology, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. His research interests include the protection and management of archaeological heritage, the theory and methodology of archaeology, contemporary archaeology, and social functions of the past in the present.

Violetta Rezler-Wasielewska

Violetta Rezler-Wasielewska (Ph.D. 2000, University of Opole) is a Director of the Central Museum of Prisoners of War. Her research interests include prisoners of war during the Second World War, microhistory, and sites of national remembrance.

Piotr Wroniecki

Piotr Wroniecki (M.A. 2011, University of Warsaw) is an expert in non-invasive prospection focused on remote sensing, geophysics, and the application of digital technology in archaeological research.

Joanna Wysocka

Joanna Wysocka is a Ph.D. candidate at the Hirszfeld Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, Polish Academy of Sciences. She is a biological anthropologist with a focus on paleopathology and an interest in forensic anthropology.

Michał Czarnik

Michał Czarnik (M.A. 2019, University of Rzeszów) is a Ph.D. candidate at the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Rzeszów with an interest in the archaeology of the recent past and of the Great War.

References

- Archive 1. Archiwum Centralnego Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych, Relacje i wspomnienia, signature 6, 20, 61, 95.

- Archive 2. The National Archives Kew, signature WO 361-1786-1 Obituary.

- Archive 3. Archive of the Information and Search Office of the Polish Red Cross in Warsaw—APCK, signature LS 59228.

- Archive 4. Arolsen Archives International Center on Nazi Persecution—AROLSEN, Lists of all Persons of United Nations and other Foreigners, German Jews and Stateless Persons, Various Zones, signature 2.1.8.1.

- Banaszek, Ł, and M. Wosińska 2011. Sztutowo czy Stutthof? Oswajanie Krajobrazu Kulturowego. Poznań, Sztutowo: Muzeum Stutthof w Sztutowie.

- Bem, M., and W. Mazurek. 2012. Sobibór. Badania Archeologiczne Prowadzone na Terenie po Byłym Niemieckim Ośrodku Zagłady w Sobiborze w Latach 2000–2011. Warszawa, Włodawa: Fundacja „Polsko-Niemieckie” Pojednanie.

- Bernbeck, R. 2018. “An Emerging Archaeology of the Nazi Era.” Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 361–367.

- Blau, S. 2015. “Working as a Forensic Archaeologist and/or Anthropologist in Post-Conflict Contexts: A Consideration of Professional Responsibilities to the Missing, the Dead and Their Relatives.” In: Ethics and the Archaeology of Violence. Ethical Archaeologies: The Politics of Social Justice, vol. 2, edited by A. González-Ruibal and G. Moshenska, 215-228. New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1643-6_13.

- Borkowski, T. 2021. Sprawozdanie z archeologicznych badań wykopaliskowych na terenie starego cmentarza jenieckiego w Łambinowicach, gm. Łambinowice, pow. nyski, woj. opolskie w dniach 25.05.2020 r.-29.05.2020 r. (Unpublished report, Archives of the Central Museum of Prisoners of War, Opole).

- Ciasnocha, R., and D. Dzionek. 2006. “Obóz Jeniecki w Latach I Wojny Światowej.” In Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870-1946), edited by E. Nowak, 67–96. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Čičiurkaitė, I. 2022. “Investigating Two Mass Grave Sites of WWII POW Camps in Lithuania.” Scandinavian Journal of Forensic Science 28: 20–31. doi: 10.2478/sjfs-2022-0014.

- Desfossés, Y., A. Jacques, and G. Prilaux. 2008. L'archéologie de la Grande Guerre. Rennes: Ouest France.

- Doyle, P., J. Pringle, and L. E. Babits. 2013. “Stalag Luft III: The Archaeology of an Escaper’s Camp.” In Prisoners of War. Archaeology, Memory, and Heritage of 19th- and 20th-Century Mass Internment, edited by H. Mytum, and G. Carr, 129–144. New York: Springer.

- Dukaczewski, D., Z. Bochenek, A. Karwel, H. Paradysz, and Z. Kulikowski. 2017. “Wykorzystanie Danych Teledetekcyjnych do Poszukiwania Miejsc Wskazujących na Obecność jam Grobowych Ofiar Obławy Augustowskiej.” Rocznik Geomatyki 15 (1(76): 63–78.

- Fernández-Álvarez, J. P., D. Rubio-Melendi, A. Martínez-Velasco, J. K. Pringle, and H. D. Aguilera. 2016. “Discovery of a Mass Grave from the Spanish Civil War Using Ground Penetrating Radar and Forensic Archaeology.” Forensic Science International 267: e10–e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.05.040.

- Freund, R. A. 2019. The Archaeology of the Holocaust: Vilna, Rhodes, and Escape Tunnels. Lanham-Boulder-New York-London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Gilead, I., Y. Haimi, and W. Mazurek. 2009. “Excavating Nazi Extermination Centers.” Present Past 1: 10–39.

- Godziemba-Maliszewski, W. 1995. “Interpretacja Zdjęć Lotniczych Katynia w Świetle Dokumentów i Zeznań Świadków.” Fotointerpretacja w Geografii 25: 16–105.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2019. An Archaeology of the Contemporary Era. London: Routledge.

- Jasiński, M. 2018. “Predicting the Past – Materiality of Nazi and Post-Nazi Camps: A Norwegian Perspective.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22: 639–661.

- Karski, K. 2020. “Archeologia Nadmiaru. Podsumowanie Wyników Badan Archeologicznych KL Plaszow z lat 2016–2019.” Krzysztofory. Zeszyty Naukowe Muzeum Historycznego Miasta Krakowa 38: 41–68.

- Karski, K., and D. Kobiałka. 2021. “Archaeology in the Shadow of Schindler’s List: Discovering the Materiality of Plaszow Camp.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 8 (1): 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.43381.

- Kiarszys, G. 2019. Atomowi Żołnierze Wolności: Archeologia Magazynów Broni Jądrowej w Polsce. Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego.

- Kisielewicz, D., and H. Niestrój. 2006. “Obóz dla Jeńców Francuskich (1870-1871).” In Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870-1946), edited by E. Nowak, 53–66. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Kobiałka, D. 2017. “Airborne Laser Scanning and 20th Century Military Heritage in the Woodlands.” Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia 12: 247–269.

- Kobiałka, D. 2018. “100 Years Later: The Dark Heritage of the Great War at a Prisoner-of-War Camp in Czersk, Poland.” Antiquity 92 (363): 772–787. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.67.

- Kobiałka, D. 2022. “Curating the Great War in Poland: The Prisoner-of-War Camp at Czersk.” In Curating the Great War, edited by P. Cornish and N. Saunders, 161-175. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003263531-12.

- Kobiałka, D., K. Kajda, and M. Frąckowiak. 2015. “Archaeologies of the Recent Past and the Soviet Remains of the Cold War in Poland: A Case Study of Brzeźnica-Kolonia, Kłomino and Borne Sulinowo.” Sprawozdania Archeologiczne 67: 9–22.

- Kobiałka, D., K. Karski, M. Pawleta, A. Lokś, E. Góra, V. Rezler-Wasielewska, M. Kostyrko, D. Nita, P. Torłop, A. Czerner, P. Stanek, M. Michalski, S. Tomczak, P. Wroniecki, S. Ważyński, Z. Kowalczyk, and R. Kasztelan R. 2023a. “Artefakty są Jedynie Środkiem do Informacji, jak Kiedyś Żyli Ludzie. Projekt Naukowy w Łambinowicach.” Odkrywca 5 (292): 16–23.

- Kobiałka, D., M. Kostyrko, A. Lokś, K. Karski, V. Rezler-Wasielewska, P. Stanek, A. Wickiewicz, E. Góra, S. Tomczak, and M. Pawleta. 2023b. “’Hell Camp’ Hidden in the Forest – the Materiality of Stalag VIII B (344) Lamsdorf.” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 18 (2-3): 97–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2023.2288959.

- Kobiałka, D., M. Pawleta, K. Karski, M. Kostyrko, A. Lokś, V. Rezler-Wasielewska, P. Stanek, A. Czerner, E. Góra, M. Michalski, S. Tomczak, Z. Kowalczyk, S. Ważyński, and P. Wroniecki. 2023c. “Camp Archaeology at the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice (Formerly Lamsdorf), Poland.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-023-00700-y.

- Kobiałka, D., M. Pawleta, K. Karski, M. Kostyrko, A. Lokś, V. Rezler-Wasielewska, P. Stanek A. Czerner, E. Góra, M. Michalski, S. Tomczak, Z. Kowalczyk, and P. Wroniecki. 2023d. “Scientific Review and Cultural Significance of the Site of National Remembrance in Łambinowice, Poland.” Antiquity 97 (396): e35, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2023.132.

- Kola, A. 2000. Bełżec. The Nazi Camp for Jews in the Light of Archaeological Sources. Excavations 1997–1999. Warsaw, Washington: The Council for the Protection of Memory of Combat and Martyrdom, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Kostyrko, M., and D. Kobiałka. 2020. “Small and Large Heritage of the Great War: An Archaeology of a Prisoner of War Camp in Tuchola, Poland.” Landscape Research 45 (5): 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1736533.

- Kuryłowicz, A., M. Koziak, and K. Kozioł. 2017. “Interaktywna Mapa Obozu Koncentracyjnego KL Płaszów w Aplikacji ArcGis Story Map.” Rocznik Geomatyki 15 (3(78): 319–333.

- Łukowski, S. 1965. Zbrodnie Hitlerowskie w Łambinowicach i Sławęcicach na Opolszczyźnie w Latach 1939–1945. Opole: Instytut Śląski w Opolu, Wydawnictwo „Śląsk”.

- Michalski, M. 2022. Analiza i opracowanie aspektów przestrzennych w wybranych relacjach jeńców polskich w powiązaniu z interpretacją historycznych zdjęć lotniczych oraz planów terenu dawnego obozu jenieckiego w Łambinowicach. (Unpublished report, Archives of the Central Museum of Prisoners of War, Opole).

- Michalski, M. 2023. Dodatkowe kwerendy materiałów archiwalnych w postaci historycznych zdjęć lotniczych dotyczących obszaru tzw. Starego Cmentarza Jenieckiego w oparciu o wnioski z pierwszego etapu badań. (Unpublished report, Archives of the Central Museum of Prisoners of War, Opole).

- Michalski, M., and S. Różycki. 2021. “Potencjał Archiwalnych Zdjęć Lotniczych w Badaniach Kompleksu Obozowego Lamsdorf 344.” In Szkice z Dziejów Obozów w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach. Historia i Współczesność 6, edited by P. Stanek, 76–102. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych.

- Morsch, G. 2016. “Die Bedeutung der Archäologie Für dIehistorische Forsuchung, Für AUsstellungen, PädagogischeVermittlung und Neugestaltung in der NS-Gedenkstäten.” In NS-Lagerstandorte. Erforschen – Bewahren –Vermitteln, edited by T. Kersting, C. Thuene, A. Drieschner, A. Ley, and T. Lut, 17–29. Petersberg: Archäologie und Gedächtins.

- Moshenska, G. 2008. “Ethics and Ethical Critique in the Archaeology of Modern Conflict.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 41 (2): 159–175.

- Moshenska, G., and A. Myers. 2011. “An Introduction to Archaeology of Internment.” In Archaeology of Internment, edited by G. Moshenska, and A. Myers, 1–19. New York, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London: Springer.

- Newson, P., and R. Young. 2022. “Post-Conflict Ethics, Archaeology and Archaeological Heritage: A Call for Discussion.” Archaeological Dialogues 29 (2): 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203822000253.

- Nowak, E. 1993. “Dokumentacja Obozów Jenieckich w Lamsdorf (Łambinowice) w Archiwach Moskiewskich.” Śląsk Opolski 10 (3): 21–26.

- Nowak, E. 2006a. Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870-1946). Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Nowak, E. 2006b. “Obóz Pracy w Łambinowicach.” In Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870-1946), edited by E. Nowak, 261–298. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Ossowski, A., M. Bykowska-Witowska, T. Manteuffel, and P. Brzeziński. 2018. “Application of Analysis of Aerial Photographs in Search of Burial Sites of Victims of War and Totalitarian Crimes.” Issues of Forensic Science 299 (1): 77-90.

- Pawlik, K., and V. Rezler-Wasielewska. 2006. “Obóz dla Imigrantów Niemieckich (1921-1924).” In Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870-1946), edited by E. Nowak, 97–116. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Pollock, S., and R. Bernbeck. 2016. “The Limits of Experience: Suffering, Nazi Forced Labor Camps, and Archaeology.” Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 27 (1): 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/apaa.12072.

- Popielski, B. 1984. “Pamięci Profesora Tadeusza Pragłowskiego.” Archiwum Medycyny Sądowej i Kryminalnej 34 (1): 1–8.

- Rezler-Wasielewska, V. 1995. “Łambinowickie Cmentarze Jenieckie w Świetle Najnowszych Ustaleń.” Łambinowicki Rocznik Muzealny 18: 27–41.

- Rezler-Wasielewska, V. 1998. “Stary Cmentarz Jeniecki w Łambinowicach. Wyniki Inwentaryzacji.” Szkice z dziejów obozów w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach. Historia i współczesność 1: 132–154.

- Rezler-Wasielewska, V. 2000. “Sprawa Pochówku Jeńców Obozów Lamsdorf (1939-1945.” Łambinowicki Rocznik Muzealny 23: 45–68.

- Rezler-Wasielewska, V. 2017. Muzeum w Miejscu Pamięci. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych.

- Saunders, N. J. 2012. “Introduction. Engaging the Materialities of 20th and 21st Century Conflict.” In Beyond the Dead Horizon: Studies in Modern Conflict Archaeology, edited by N. J. Saunders, x–xiv. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Sawczuk, J. 1974. Hitlerowskie Obozy Jenieckie w Łambinowicach w Latach 1939-1945. Opole: Instytut Śląski.

- Sawczuk, J., and S. Senft. 2006. “Obozy Jenieckie w Lamsdorf w Latach II Wojny Światowej.” In Obozy w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach (1870/1946), edited by E. Nowak, Opole, 117-260. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Senft, S. 2000. “Włoscy Jeńcy Wojenni w Stalagu 344 Lamsdorf.” In Szkice z Dziejów Obozów w Lamsdorf/Łambinowicach. Historia i Współczesność 2, edited by E. Nowak, 61–73. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych.

- Stanek, P. 2017. Wrześniowy Epilog. Żołnierze Wojska Polskiego w Obozach Lamsdorf. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Steele, C. 2008. “Archaeology and the Forensic Investigation of Recent Mass Graves: Ethical Issues for a New Practice of Archaeology.” Archaeologies 4: 414–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-008-9080-x.

- Sturdy Colls, C. 2015. Holocaust Archaeologies. Approaches and Future Directions. New York: Springer.

- Sturdy Colls, C., J. Kerti, and K. Colls. 2020. “Tormented Alderney: Archaeological Investigations of the Nazi Labour and Concentration Camp of Sylt.” Antiquity 94 (374): 512–532. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2019.238.

- Thomas, S. 2019. “Doing Public Participatory Archaeology with “Difficult” Conflict Heritage: Experiences from Finnish Lapland and the Scottish Highlands.” European Journal of Post Classical Archaeologies 9: 147–167.

- Tucholski, Z. 2019. “Fotografia Lotnicza Jako Źródło Historyczne.” Kwartalnik Historii Nauki i Techniki 64 (2): 167-179.

- Uryga, L. 1978. “Stalag VIII B Zabudowa i Zakwaterowanie Jeńców w Obozie. Jeńcy Wojenni w Niewoli Wehrmachtu.” Łambinowicki Rocznik Muzealny 2: 13–31.

- Uryga, L. 1982. Łambinowice. Geneza i Anatomia Zbrodni. Opole: Muzeum Martyrologii i Walki Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach.

- Wickiewicz, A. 2016. Niewola w Brytyjskim Mundurze. Stalag VIII B (334) Lamsdorf. Opole: Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych w Łambinowicach-Opolu.

- Więcek, H. 1969. Jeńcy Polscy w Obozie Hitlerowskim w Łambinowicach (1939-1940). Studia Śląskie. Seria Nowa 16. Opole: Instytut Śląski w Opolu.