The use of psychoactive substances, including cannabis, has accompanied the development of civilization (Citation1). (In the context of this paper, “psychoactive substances” refers specifically to substances that produce pleasurable and rewarding effects). For millennium, many of these substances have been widely used as medicinals, in religious ceremonies, and as recreational intoxicants. Their misuse (use that results in problems related to intoxication or excessive consumption), however, has historically been viewed as a moral failing, a character defect, a disruption in cognition, coping, or stress tolerance, and/or a problem within the social-cultural-legal milieu (e.g., the availability of an irresistible euphoriant). Of particular relevance to the past century, there has been an ongoing struggle between perceiving the use of psychoactive substances as socially acceptable and legal (e.g., alcohol, nicotine and caffeine in the West, khat in many Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula countries, and coca in some South American countries), as dangerous or sinful in any amount and necessitating punishment from law enforcement (the temperance perspective), and/or, when used in an addictive manner, as a medical illness requiring treatment (the brain disease perspective) (Citation2). The predominant approach employed in response to the use of a specific substance in any given jurisdiction has typically shown little correlation with a substance’s intoxicating effect or its harm to the individual or society (Citation3). Rather, legal status of a substance has been product of a region’s societal-cultural-religious-historical preferences and perceptions (Citation1), substance-related societal disruptions (Citation4), economic concerns (Citation5,Citation6), and political expediency (Citation7).

In many countries, particularly in the Western world, the balance between the temperance model (with its concomitant legal constraints) and the medical model has been particularly fraught over the past century (Citation4). In the United States, for instance, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act in 1909 banned the possession, importation and use of opium for smoking and the 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act (Citation8) restricted the manufacture and sale of cannabis, cocaine, heroin, and morphine. In 1919, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, banning the manufacture, transportation or sale of alcohol (but not its use). In 1930, the Treasury Department created the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (Citation9) and illicit substances were increasingly criminalized. The 1937 “Marihuana Tax Act” taxed the sale of cannabis and hemp (Citation10) and the 1951 Boggs Act drastically increased the penalties for cannabis possession (Citation11). The Narcotics Control Act of 1956 created “the most punitive and repressive anti-narcotics legislation ever adopted by Congress (Citation12).” In 1971, President Richard Nixon declared a “War on Drugs,” proclaiming “America’s public enemy number one in the United States is drug abuse” (Citation13) and the Drug Enforcement Agency was created in 1973 (Citation14). In 1986, Congress passed The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (Citation15), significantly increasing the penalties for crack cocaine (Citation16) (a drug used predominantly by black Americans). These punitive approaches have resulted in decades of massive arrests and incarcerations, particularly of persons of color, without suppressing rates of substance use or misuse (Citation17).

Concurrently, other forces in the U.S. were approaching substance use and misuse from a medical model perspective. The medical model posits that an illness is the result of one’s biology and that medical treatment, if available, is the optimal intervention. This is standard operating procedure in the rest of medicine, including psychiatry; an individual is not punished by the state for suffering from an illness. In the early decades of the last century, for example, many U.S. physicians and informal “narcotic clinics” prescribed maintenance doses of opioids to treat addicted individuals, allowing them to avoid withdrawal and maintain stability (a practice eventually discontinued as many physicians and pharmacists were arrested as a result of the Harrison Narcotics Act (Citation4)). Many decades following, the 1966 Narcotics Addict Rehabilitation Act recognized that the disease concept of alcoholism also applied to drug addiction and specified that “narcotic addiction” was a mental illness (Citation18). Despite Nixon’s call for a War on Drugs, two-thirds of the funds dedicated to the drug war were targeted for prevention, education, treatment and research (Citation19). Beginning in 1989, “drug courts” increasingly allowed individuals arrested for drug-related crimes to be diverted to treatment rather than incarceration (Citation20). Harm-reduction techniques (policies, programs and practices to minimize the negative health, social and legal impacts associated with drug use, drug policies and drug laws (Citation21)), such as opioid agonist therapy (methadone, buprenorphine (Citation22,Citation23)), needle exchange for the prevention of HIV and hepatitis C transmission (Citation24), and naloxone distribution for the treatment of opioid overdose (Citation25) became increasingly utilized over the ensuing decades. Harm reduction approaches to illicit substance use is perhaps best personified in the U.S. by the LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion) program, a public safety program which allows police officers discretionary authority to divert individuals suspected of low level, nonviolent crime to community-based health services instead of arrest, jail and prosecution (Citation26). Other countries have progressed even further: Portugal has decriminalized all drug use (Citation27,Citation28); Europe and Canada have, on a small scale, implemented heroin-assisted treatment (Citation29,Citation30) and supervised injection sites/drug consumption facilities (Citation31).

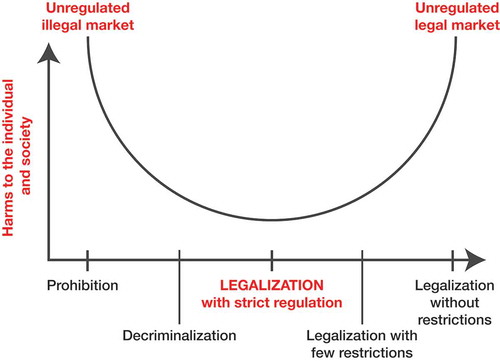

The conflicting and inharmonious temperance-infused drug prohibition and harm reduction approaches are part the broader backdrop in which cannabis legalization is occurring. (Citation32,Citation33) illustrates the tension inherent in the temperance-based approach: both cannabis prohibition (the most severe, temperance-based response) and the removal of all legal restraint (legalization without restriction) result in significant harm to the individual and to society. A true harm-reduction model, as represented by “Legalization with Strict Regulation,” should minimize the individual, social, and economic costs of cannabis prohibition while protecting the individual and society from the harmful effects of the unregulated cultivation, sale and use of the drug (legalization without regulation). It is the balance between the extremes of cannabis prohibition and unregulated legalization, and how to assure that the optimal equilibrium is achieved, that has been the topic of this Special Issue on the Benefits and Consequences of Cannabis Legalization. As elegantly expressed by Caulkins and Kilborne, “there is … a conceptual tension between the twin goals of minimizing harmful use and minimizing black [illicit] market activity. Addressing either in isolation is straightforward; balancing them is not” (Citation34). The editors have approached this Special Issue with the assumption that there is no perfect answer and that there will be both positive and negative outcomes from cannabis legalization. It is hoped that, over the long run, the positives will outweigh the negatives.

Figure 1. Cannabis policies and relative harm. Adapted from (Citation32,Citation33) with permission from Alice Rap (www.alicerap.eu) and Center for Addiction and Mental Health (www.camh.ca).

Adinoff and Reiman (Citation17) make the case that one of the most overt and immediate societal gains from cannabis and legalization —from our perspective, one without a downside—is the benefits that arise from decreasing cannabis-related arrests and incarcerations and the associated personal economic and emotional costs. These benefits will significantly expand if expungement is extended to all individuals previously convicted of cannabis-related offenses (Citation17,Citation35,Citation36), although the specifics of whose record to expunge (or reduce) and the process of expungement (by petition or automatic) remains variable—assuming expungement is offered at all (Citation17,Citation36). Given the significantly greater likelihood of persons of color being arrested for cannabis-related offenses in the U.S., it is presumed that this population will most benefit from cannabis legalization and expungement (Citation17). The decrease in arrests and incarcerations should also produce significant savings for law enforcement (Citation36). These savings assume that the illicit market can, over time, be minimized and the costs of securing a regulated market is not overly burdensome. Other important benefits of a regulated market include substantial tax revenue, reducing the criminal element in cannabis cultivation, distribution and sale, restricted access to cannabis by youth, having a controlled and regulated market that assures the consumer is informed of cannabis dosages and quality and access to medical cannabis for the treatment of various illnesses (Citation37).

The critical question, of course, is whether or not these benefits are feasible and, even if achieved, will they be outweighed by the harmful consequences? Given that cannabis legalization (particularly for adult, i.e. recreational, use) is still relatively new, these questions remain unanswered. Thus, the authors in this Special Issue pose questions that need to be successfully addressed to assure that, in balance, cannabis legalization is a net positive for the individual and society.

Key among these issues is whether, in fact, youth are being protected from cannabis in cannabis legal states. The good news, presented by Smart and Pacula (Citation38), is that adolescent use and misuse of cannabis in the U.S. has remained stable or even decreased in cannabis legal states. This robust literature suggests that the outcomes predicted by legalization proponents—that cannabis regulation would make it more difficult for those under 18 years old (y/o) to obtain cannabis—has been successful. For college students, the findings are more uncertain, with some studies suggestion that use is increasing (Citation38). As much of the epidemiologic data to-date consider individuals who are 18 to 20 year old “young adults” (Citation39), it may be difficult to clearly parse out this population. But as 18 to 20 year old youth are not legally allowed to purchase cannabis in the U.S. (except for medical purposes), it will be important to determine how these individuals fare relative to those 21 to 25 y/o. Comparisons with similar aged youth (i.e. 18 to 20 y/o) in Canada and Uruguay will be of interest, as these individuals can legally purchase cannabis (although some provinces in Canada restrict adult use cannabis to 19 y/o and older).

A troublesome observation by Hasin et al. (Citation39) is that while overall cannabis use has decreased in adolescents, use in the nonwhite and older adolescents in the U.S. may be increasing, suggesting that some adolescent groups may be at heightened risk. The finding of possibly higher use in nonwhite adolescents is particularly concerning, as disadvantaged groups have borne the brunt of cannabis prohibition (e.g. arrests, incarcerations) and it is hoped that cannabis legalization will be a net positive for these populations. It should be noted, however, that Hasin et al. explored cross-sectional data in the U.S. and did not compare legal vs. non-legal states; it is unknown whether these findings can be generalized to both groups of states.

In contrast to the findings in adolescents, the reviews by Smart and Pacula (Citation38) and Hasin et al. (Citation39) both conclude that cannabis use and use disorders have been increasing in adult U.S. populations—with use and use disorders increasing more in medical relative to non-medical legal cannabis states (Citation38). Similar to the findings reported for adolescents, Hasin et al. (Citation39) also reports increasing rates of cannabis use and use disorder in blacks (relative to whites) and low-income individuals. As noted, their analytic approach did not allow a comparison between cannabis legal and illegal states.

The health effects of cannabis legalization present a mixed picture. In this Special Issue, Sarne (Citation40) provides an overview of cannabinoid “duality” – the deteriorating and ameliorating effects of cannabinoids on the brain—and makes a case for the potential clinical utility of ultra-low dose tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) for both brain injuries and age-related cognitive decline. Burggen et al. (Citation41) present a comprehensive review of cannabis effects on brain structure, function and cognition. An expanding literature now strongly suggests that the recreational use of cannabis has persistent effects on brain morphology and cognition and that these are effects are likely more pronounced in adolescents. On the other hand, cannabinoids (i.e. THC and cannabidiol (CBD)) may have clinical utility in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and epilepsy. There is mixed evidence as to whether medical cannabis legalization decreases opioid-related overdoses and prescriptions written and the impact upon alcohol and nicotine use is inconclusive (Citation38). Tashkin and Roth (Citation42) discuss the numerous carcinogens and respiratory toxins inhaled when smoking cannabis flower, although the clinical significance of these toxins remain uncertain. Similarly, the clinical benefits of cannabis’ bronchodilator effects are also unclear. (This paper was accepted for publication prior to reports of pulmonary illnesses due to vaping (Citation43), although it is unlikely that these illnesses are due to THC.) The interaction between potential health benefits of cannabis and its abuse liability and neurocognitive impairment was explored by Cooper and Abrams (Citation44). This review noted that the analgesic effect of cannabis can be experienced with relatively mild adverse effects while bringing attention to the difficulty of conducting these studies in a careful manner. The health effects of cannabis legalization on driving, both to the individual using cannabis and to other drivers, also remains an area of uncertainty. Ginsburg (Citation45) addresses the difficulties in determining a net effect of cannabis on driving, one way or the other: while cannabis clearly impairs driving ability, it is uncertain whether this impairment is sufficient to increase the risk of a motor vehicle accident or whether potential cannabis-related decreases in other substance/medication use (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines, alcohol) with more marked driving impairment outweighs the negative effects of cannabis. As THC levels correlate poorly with cannabis intoxication, it has been difficult to assess the true role of recent cannabis use in motor vehicle accidents.

The above highlights the complexity of assessing the pros and cons of harm reduction approaches to substance use. The outcome will not be as straightforward as “cannabis legalization is good” or “cannabis legalization is bad.” As suggested by , the success of cannabis legalization will depend upon the specific regulatory processes that are put in place. Four papers in this Special Issue—Shover et al. (Citation35), Caulkins and Kilborn (Citation34), Kilmer (Citation36) and Adinoff and Reiman (Citation17)—stress that how cannabis is legalized will ultimately determine if public health is protected successfully. For each jurisdiction that legalizes cannabis, there are a number of issues that must be considered: who is in charge of regulation (e.g., cultivation, distribution, sale); what cannabis products can be sold (e.g., potency, purity, product types), where can they be sold and how can they be sold (e.g. marketing); how will the regulations be enforced (e.g., policing, enforcement, penalties); how will tax rates be determined to maximize revenue but limit the illicit market; who can receive licenses (e.g. assuring equity in license distribution); how will cannabis-generated tax revenue be distributed (e.g., designated for a general fund or to support regulation, prevention, treatment, restorative justice); whether to combine medical and adult use approaches; how to best protect vulnerable populations; how to support research into the health benefits and consequences of cannabis use; and how to maintain a regulatory system that is flexible and responsive to new data. The most critical issue in jurisdictions that choose to commercialize the cultivation and sale of cannabis, a potentially risky harm reduction intervention, will be their success in reining in the ever-growing influence of corporate interests to avoid the devastating pitfalls experienced with alcohol and nicotine, i.e. how to support public health when others are actively encouraging cannabis consumption (Citation46).

References

- Robinson SM, Adinoff B. The classification of substance use disorders: historical, contextual, and conceptual considerations. Behav Sci (Basel). 2016;6. doi:10.3390/bs6040028.

- Volkow ND, Koob G. Brain disease model of addiction: why is it so controversial? Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:677–79. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00236-9.

- Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4.

- Courtwright DT. A century of American narcotic policy. In: Gerstein DR, Harwood HJ, editors. Treating drug problems: volume 2: commissioned papers on historical, institutional, and economic contexts of drug treatment. Washington, DC: National Acadamies Press; 1992.

- Hall W. What are the policy lessons of national alcohol prohibition in the United States, 1920–1933? Addiction. 2010;105:1164–73. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02926.x.

- Blocker JS Jr. Did prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:233–43. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.065409.

- Baum D. Smoke and mirrors: the war on drugs and the politics of failure. New York: Little, Brown and Company; 1997.

- Harrison Narcotics Act. Chap. 1, 38 Stat. 785. 1914. Available from: http://legisworks.org/sal/38/stats/STATUTE-38-Pg785.pdf [last accessed 21 Sept 2019].

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). The early years. Available from: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-05/Early%20Years%20p%2012-29.pdf [last accessed 29 Sept 2019]

- Musto DF. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1972;26:101–08. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750200005002.

- Rothwell VL. Boggs Act. In: Kleiman MAR, Hawdon JE, editors. Encyclopedia of drug policy. Newbury Park: Sage Publishing; 2011.

- McWilliams J. The Protectors: Harry J. Anslinger and the Federal Bureau Of Narcotics, 1930–1962; Newark NJ: University of Delaware Press; 1990. p. 116

- Sharp EB. The dilemma of drug policy in the United States. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers; 1994.

- Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). DEA History Book 1970 -1975. Available from: https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-07/1970-1975%20p%2030-39.pdf [last accessed 22 Oct 2019].

- Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. H.R.5484.1986. Access 1986.

- Hatsukami DK, Fischman MW. Crack cocaine and cocaine hydrochloride. Are the differences myth or reality? JAMA. 1996;276:1580–88. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540190052029.

- Adinoff B, Reiman A. Implementing social justice in the transition from illicit to legal cannabis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:673–688. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1674862.

- Narcotic Addict Act Marks Change in Policy. 1967. Available from: http://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/cqal66-1301488 [last accessed 29 Sept 2019].

- Nixon R. Statement on establishing the office for drug abuse law enforcement. 1972. Available from: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/254830 [last accessed 29 Sept 2019].

- Brown RT. Systematic review of the impact of adult drug-treatment courts. Transl Res. 2010;155:263–74. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2010.03.001.

- Harm Reduction International. What is harm reduction? 2019. Available from: https://www.hri.global/what-is-harm-reduction [last accessed 21 Sept 2019].

- Wakhlu S. Buprenorphine: a review. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:59–64.

- Hedrich D, Pirona A, Wiessing L. From margin to mainstream: the evolution of harm reduction responses to problem drug use in Europe. Drugs. 2008;15:503–17.

- Yoast R, Williams MA, Deitchman SD, Champion HC. Report of the council on scientific affairs: methadone maintenance and needle-exchange programs to reduce the medical and public health consequences of drug abuse. J Addict Dis. 2001;20:15–40. doi:10.1300/J069v20n02_03.

- Brodrick JE, Brodrick CK, Adinoff B. Legal regimes surrounding naloxone access: considerations for prescribers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42:117–28. doi:10.3109/00952990.2015.1109648.

- Collins SE, Lonczak HS, Clifasefi SL. Seattle’s law enforcement assisted diversion (LEAD): program effects on recidivism outcomes. Eval Program Plann. 2017;64:49–56. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2017.05.008.

- Hughes CE, Stevens A. What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs? Br J Criminol. 2010;50:999–1022. doi:10.1093/bjc/azq038.

- Laqueur H. Uses and abuses of drug decrminalization in Portugal. Law Social Inq. 2015;40:746–81. doi:10.1111/lsi.12104.

- Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D. Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:55–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112.

- Fischer B, Oviedo-Joekes E, Blanken P, Haasen C, Rehm J, Schechter MT, Strang J. van den Brink W. Heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) a decade later: a brief update on science and politics. J Urban Health. 2007;84:552–62. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9198-y.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Drug consumption rooms: an overview of provision and evidence (Perspectives on drugs). 2018. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/pods/drug-consumption-rooms_en [last accessed 22 Oct 2019].

- Crepault JF. Cannabis policy framework. 2014. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs—public-policy-submissions/camhcannabispolicyframework-pdf.pdf [last accessed 2 Oct 2019].

- Apfel F. Policy Brief 5. Cannabis - from prohibition to regulation. 2016. Available from: http://fileserver.idpc.net/library/ALICE-RAP-Policy-Paper-Cannabisfrom-Prohibition-to-Regulation.pdf [last accessed 3 Oct 2019].

- Caulkins JP, Kilborn ML. Cannabis legalization, regulation, & control: a review of key challenges for local, state, and provincial officials. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:689–697. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1611840.

- Shover CL, Humphreys K. Six policy lessons relevant to cannabis legalization. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:698–706. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1569669.

- Kilmer B. How will cannabis legalization affect health, safety, and social equity outcomes? It largely depends on the 14 Ps. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:664–672. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1611841.

- Caulkins JP, Kilmer B, MacCoun RJ, Pacula RL, Reuter P. Design considerations for legalizing cannabis: lessons inspired by analysis of California’s Proposition 19. Addiction. 2012;107:865–71. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03561.x.

- Smart R, Pacula R. Early evidence of the impact of cannabis legalization on cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and the use of other substances: findings from state policy evaluations. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:644–663. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1669626.

- Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Sarvet AL. Time trends in US cannabis use and cannabis use disorders overall and by sociodemographic subgroups: a narrative review and new findings. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:623–643. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1569668.

- SarneY. Beneficial and deleterious effects of cannabinoids in the brain: the case of ultra-low dose THC. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;551–562. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1578366.

- Burggren AC, Shirazi A, Ginder N, London ED. Cannabis effects on brain structure, function, and cognition: considerations for medical uses of cannabis and its derivatives. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019:563–579. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1634086.

- Tashkin DP, Roth MD. Pulmonary effects of inhaled cannabis smoke. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:596–609. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1627366.

- Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, Kimball A, Layer M, Tenforde M, Navon L, Hoots B, Salvatore PP, Elderbrook M, et al. Pulmonary illness related to E-cigarette use in Illinois and Wisconsin - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2019. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911614.

- Cooper ZD, Abrams DI. Controlled clinical studies examining both therapeutic and abuse-related outcomes of cannabis use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019.

- Ginsburg BC. Strengths and limitations of two cannabis-impaired driving detection methods: a review of the literature. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2019;45:610–622. doi:10.1080/00952990.2019.1655568.

- Crepault JF. Cannabis legalization in Canada: reflections on public health and the governance of legal psychoactive substances. Front Public Health. 2018;6:220. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00220.