Abstract

Background: Medical students need to be trained in delivering diversity-responsive health care but unknown is what competencies teachers need. The aim of this study was to devise a framework of competencies for diversity teaching.

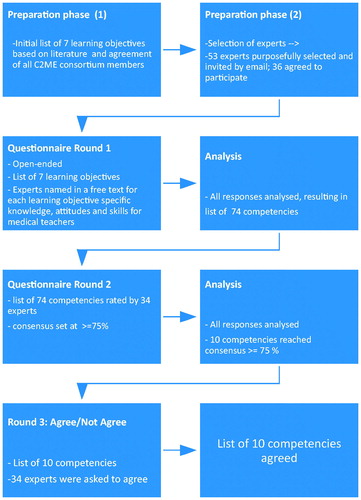

Methods: An open-ended questionnaire about essential diversity teaching competencies was sent to a panel. This resulted in a list of 74 teaching competencies, which was sent in a second round to the panel for rating. The final framework of competencies was approved by the panel.

Results: Thirty-four experts participated. The final framework consisted of 10 competencies that were seen as essential for all medical teachers: (1) ability to critically reflect on own values and beliefs; (2) ability to communicate about individuals in a nondiscriminatory, nonstereotyping way; (3) empathy for patients regardless of ethnicity, race or nationality; (4) awareness of intersectionality; (5) awareness of own ethnic and cultural background; (6) knowledge of ethnic and social determinants of physical and mental health of migrants; (7) ability to reflect with students on the social or cultural context of the patient relevant to the medical encounter; (8) awareness that teachers are role models in the way they talk about patients from different ethnic, cultural and social backgrounds; (9) empathy for students of diverse ethnic, cultural and social background; (10) ability to engage, motivate and let all students participate.

Conclusions: This framework of teaching competencies can be used in faculty development programs to adequately train all medical teachers.

Introduction

All European countries are experiencing increasing ethnic diversity, a trend that is reinforced by the recent entering of large groups of refugees in the European Union. While the ongoing migration necessitates that care delivered by European care providers is tailored to the needs of a diverse patient population, this also presents specific challenges to care providers, such as communicating with patients across language barriers, misunderstandings between patients and care providers due to cultural differences in illness and treatment perceptions, and inappropriate care because of providers' prejudices against or stereotypical ideas regarding immigrant patients (Suurmond et al. Citation2010). It is believed that this may result in ethnic disparities in health (Smedley and Nelson Citation2002).

To provide good quality of care to all patients, care providers need to be able to acknowledge, recognize and deal with these challenges. One approach to ensure this requires that care providers acquire cultural competencies, that is, specific knowledge, attitudes and skills to care for patients of different cultural, ethnic and social background (Horvat et al. Citation2014; Napier et al. Citation2014; Truong et al. Citation2014).

For care providers to acquire cultural competencies, they need to be taught these in their medical education programs. However, research has found that medical teachers have limited training in cultural competencies (Berger et al. Citation2014; Lu et al. Citation2014). As a result, they feel insecure about teaching cultural competencies to students (Lu et al. Citation2014), and feel they lack adequate knowledge and skills in their teaching (Kai et al. Citation2001; Berger et al. Citation2014). This situation may be explained by the fact that detailed understanding and standardized training frameworks for medical teachers are lacking (Betancourt and Green Citation2010), and there is no agreement about what the core competencies for medical teachers should be. It is generally acknowledged that medical educators would appreciate cultural competence training (Berger et al. Citation2014; Sörensen et al. Citation2017) but what the overall goals of such training should be is still unclear. In order to fill this knowledge gap, we aimed at defining consensus among international experts about a framework of core competencies that all teachers need in order to deliver high-quality teaching about ethnic and cultural diversity. We carried out this study as part of the C2ME (Culturally Competent in Medical Education) project (2013-2015), which was an European project funded by the EACEA ERASMUS Life Long Learning Program, managed by the Academic Medical Centre/University of Amsterdam, involving 12 medical schools in 11 European countries (www.amc.nl/C2ME). We present this paper to describe the research journey of the C2ME project but also to provide colleagues across Europe with a framework to develop faculty development programs and to evaluate teaching. We believe that a detailed understanding of the core competencies of medical teachers to teach cultural competencies to medical students is necessary to provide students with the competencies to care for diverse patient populations. This competency set will allow medical teachers and trainers to set priorities and focus around strengthening the cultural competencies of medical teachers.

Methods

Design

A Delphi method was used to reach group consensus by determining the extent to which experts agreed on the core competences (Murphy Citation1998). The Delphi method consists of a series of rounds, in which a panel of experts rates items in terms of their importance. The Delphi method was chosen for this study because this method is useful for generating ideas about topics on which scientific knowledge is still scarce and when it is difficult to carry out a face to face study (Boulkedid et al. Citation2011; Moynihan et al. Citation2015). The Delphi method has been effectively used before to define competencies (Humphrey-Murto et al. Citation2017) and to examine core cultural competencies important for care providers to deliver care to ethnically and culturally diverse patient populations (Kim-Godwin et al. Citation2006; Jirwe et al. Citation2009).

A three-round process was adapted. The first round consisted of an open-ended questionnaire inviting experts’ view on what competencies were relevant for medical teachers. This formed the basis of the second round questionnaire, in which experts were asked to prioritize and rank the competencies identified. In the final round, the experts were asked to agree with a list of competencies.

Sample

We used a purposeful sample in order to select participants who could provide various perspectives about all the possible competencies deemed important for medical teachers. Every partner in the C2ME consortium appointed four to five health care professionals with affinity to teaching cultural and diversity issues within their country. These professionals were seen as experts in the field of cultural competence (e.g. they taught cultural competencies in the medical curriculum or were involved in policy regarding cultural competencies in the medical curriculum). The Delphi study was carried out in English as all experts were proficient in English.

There is no strict rule to define the number of experts in a Delphi study but the panel usually has between 20-50 participants (Jirwe et al. Citation2009). In our study, 53 experts were initially invited in the first round. Thirty-six experts from 11 European countries (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (Great Britain and Scotland) accepted the invitation. They categorized themselves as medical doctor (21), nurse (6), social scientist (7), educational specialist (5), psychologist (2) and/or other such as public health scientists (6). The Delphi panels ran between January and June 2014. All 36 participants completed round 1, 34 participants completed round 2 and round 3. In all rounds, we collected the data using a questionnaire sent to the experts via email.

To avoid dominance by members who, for example, are in a position of authority, we maintained the anonymity of the panelists by sending emails to each panelist individually.

Data collection

In preparation to the first round, we developed a list of seven learning objectives for teaching cultural and ethnic diversity. This list summarizes learning objectives that other authors have identified before (Betancourt Citation2003; Seeleman et al. Citation2009) and still identify as important learning objectives (Constantinou Citation2017). The learning objectives are related to knowledge (e.g. students should have knowledge about how social and cultural factors affect health of patients), attitudes (e.g. students should have awareness of implicit attitudes and how values and biases may affect health care provision) and skills (e.g. students should have the ability to work effectively with an interpreter). The list was sent to all members of the C2ME consortium (all experts in culturally competent medical education) and was agreed upon by all. The final list is presented in .

Table 1. Questionnaire used in the first round of the Delphi study.

In round 1, the learning objectives identified in were collated into an open-ended questionnaire, in which experts could name in a free text response for each identified learning objective which specific knowledge, attitudes and skills they believed medical teachers should ideally possess in order to effectively teach this learning objective to medical students at the preclinical and clinical levels. Free text information about learning objectives that experts felt were missing from the initial list, could be added (). Additional information was asked (professional employment; type of teaching involved).

The answers were assembled in preparation for the second round in which a list was constructed of all the specific knowledge, attitudes and skills that were mentioned by the experts. This list of 74 items was arranged using the literature on teaching competencies (Molenaar et al. Citation2009) which included the following general teaching competencies for medical teachers: (1) Execution of teaching; (2) Coaching of the learning process of students; (3) Development of teaching materials and programs; (4) Organization of teaching; (5) Evaluation of the educational process; (6) Development of formative (feedback) and summative (decisive) assessment. This list of consensus of items was presented in round two to the panel and participants were asked to rate the importance of each listed competency as one of the following:

“Essential for all teachers – it is essential that teachers will achieve this competency, to provide culturally competent teaching”

“Desirable for all teachers – it is desirable that teachers will achieve this competency, to provide culturally competent teaching”

“Unnecessary for any teacher – it is unnecessary that teachers will achieve this competency, to provide culturally competent teaching”

The analysis of round two yielded a revised list of competencies that was sent in round three to the experts and which asked experts to (dis)agree and/or to send further feedback. In , the process of the Delphi study is summarized.

Data analysis

The results of round 1 were analyzed using a qualitative thematic analysis (Ritchie and Spencer Citation1993; Pope et al. Citation2000). Two authors (RH and JS) read and reviewed the data independently in order to identify key themes and subthemes. The themes and subthemes were discussed, similar subthemes were removed, and both authors finally agreed upon a list of 74 teaching competencies. For round two, this list of teaching competencies was ranked by the participants. We calculated a mean rate of the score on “Essential for all teachers” for each of the competencies. While there is no agreement in the literature on what an appropriate consensus level is, we used an a priori set consensus rate of 75% as suggested by Keeney (Keeney et al. Citation2006).

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Dutch NVMO Ethical Review Board. The ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and adopted by the World Medical Association were followed. Codes were used to designate the respondents to guarantee their anonymity. Each respondent was adequately informed of the aims and methods of the study, and a priori informed consent was obtained from the respondents for their participation in this study.

Results

In the first round, 36 experts participated in the panel (68% response rate). All participants completed round one, resulting in a list of 74 teaching competencies. In the second round, this list was presented and ranked by 34 experts. Analysis after this round yielded a consensus rate of 75% for 10 competencies that were seen as essential for all teachers: (1) ability to critically reflect on own values and beliefs; (2) ability to communicate about individuals in a nondiscriminatory, non-stereotyping way; (3) empathy for patients regardless of ethnicity, race or nationality; (4) awareness of intersectionality; (5) awareness of own ethnic and cultural background; (6) knowledge of ethnic and social determinants of physical and mental health of migrants; (7) ability to reflect with students on the social or cultural context of the patient relevant to the medical encounter; (8) awareness that teachers are role models in the way they talk about patients from different ethnic, cultural and social backgrounds; (9) empathy for students of diverse ethnic, cultural and social background; (10) ability to engage, motivate and let all students participate. The items presented in are the results from round 2.

Table 2. Teaching competencies reaching 75 % consensus.

This list was approved in the 3rd round with no further changes.

Discussion

This consensus study led to the determination of 10 competencies that are seen as essential for all medical teachers to teach ethnic and cultural diversity issues to medical students. High response rate to both rounds and from a wide stakeholder group implies endorsement of the importance of a framework describing core competencies for medical teachers.

The 10 competencies defined through this process readily fit under the following two competencies from Molenaar et al’s framework of the six general key teaching competencies (Molenaar et al. Citation2009):

Execution of teaching

Coaching of the learning process of students

The competencies falling under the four remaining key competencies from the framework by Molenaar (i.e. (3) Development of teaching materials and programs; (4) Organization of teaching; (5) Evaluation of the educational process) and (6) Development of assessment) did not receive enough consensus. Participants’ comments indicated that teaching competencies falling under these rejected key competencies were too specific for most medical teachers, and therefore not essential for all teachers. According to the participants, some of these key competencies could, however, be relevant for teachers who are specifically involved in the teaching of ethnic and cultural diversity issues, for example, the competency to develop teaching materials about cultural competence or diversity of patients. Notably, while teaching cultural competencies are generally seen as a discipline in which attitudes are important (Nazar et al. Citation2015), the defined competency set places emphasis on awareness and reflexivity. The three competencies that had the most consensus (more than 90%) were, respectively, awareness that teachers are role models in the way they talk about patients from different ethnic, cultural and social backgrounds (91%), the ability of teachers to communicate about individuals from different ethnic, social and cultural groups in a nondiscriminatory, nonstereotyping way (91%) and the ability of teachers to critically reflect on own values and beliefs (93%). Reflexivity cannot be achieved without awareness of the context in which students’ norms and values exist, as well as awareness of a teacher’s own ethnic and (sub)cultural background/standards (76% consensus). Only then, insight into the systematic issues that determine and sustain differences in health outcomes can be obtained (Kumagai and Lypson Citation2009).

A related competence that we found is the ability for teachers to reflect with students on the social or cultural context of the patient relevant to the medical encounter (e.g. diagnosis-telling and decision-making in case of cancer treatment, organ transplantation, palliative care) (75% consensus). Particularly in case of ethical dilemmas, cultural differences between care provider and patient become visible. While this teaching competency is seen as essential by our panel, research has found that medical teachers feel limited in their ability to teach these issues to students. They find it difficult to teach in cases of cultural conflict or cultural dilemma, for example on how to conduct culturally sensitive physical examinations, how to counsel patients in culturally sensitive ways, how to address adherence to treatment from diverse patients or to elicit diverse patients’ perspectives about health and illness (Rollins et al. Citation2013).

We also found that the teaching of specific knowledge about ethnic and social determinants of health was seen as essential. The social determinants of health are the circumstances under which people live that affect their health and life chances. Factors related to health outcomes are, for example, educational attainment, occupational status, income status, access to health care services and discrimination. This competence describes that medical teachers should have knowledge about social and ethnic determinants of health for the most common and/or most vulnerable groups in the community or society. Martinez and colleagues have provided 12 tips to teach social determinants of health in medical schools (Martinez et al. Citation2015). They provide medical teachers with concrete examples of how to teach social determinants of health, but also stress the importance of teaching students self-reflection and awareness about e.g. their own cultural background and the ability to recognize their stereotypes and unconscious biases.

Another important finding is that three competencies relate to the coaching of the learning process of students. These were: having empathy (understanding and compassion) for students of diverse ethnic, cultural and social background (82%), the ability to engage, motivate and let all students participate in the learning environment (76%) and awareness that teachers are role models in the way they teach about patients from different ethnic, cultural and social backgrounds (91%). Medical teachers should be able to include all students regardless of their ethnic, cultural or social background, in their teaching. It is generally believed that this inclusive teaching may support medical students from ethnic minority backgrounds in their learning process. There is evidence that medical students from ethnic minority background underperform compared with those from the ethnic majority (Woolf et al. Citation2011) and qualitative research (Woolf et al. Citation2008) has highlighted the importance of the student–teacher relationship to learning of ethnic minority students and the possible contributory effects of for example stereotyping to their worse performance (Woolf et al. Citation2008).

Finally, we would like to point out awareness of intersectionality as an essential teaching competency. Rather than viewing cultural or ethnic identity as an isolated category, it is argued that there is interaction between gender, race, and other categories of difference in individual lives, social practices, institutional arrangements, and cultural ideologies and the outcomes of these interactions in terms of power (Powell Sears Citation2012). While our study stresses awareness of the way in which intersections of identity influence health experiences and outcomes as an essential teaching competency, intersectionality is often seen as difficult to integrate in the curriculum (Kumagai and Lypson Citation2009; Powell Sears Citation2012; Muntinga et al. Citation2016). In order to promote the use of the concept of intersectionality in medical school, Powell Sears (Citation2012) suggests different exercises, for example to support doctors to reflect on their social class and immigration status, age, sexuality, gender and geographic location.

We recommend that existing faculty development programs not only address specific topics related to the care to patients of diverse backgrounds but also to the teaching and coaching of students from diverse backgrounds. Students need explicitly “role models” who send a clear message that diversity issues are important. In addition, we recommend that teachers are supported by the medical schools, and that medical schools take responsibility to integrate cultural diversity across the entire curriculum. Hence, medical schools should develop a policy on what and how they want to teach cultural competencies and diversity issues. They should include cultural competencies either as a specific core mandatory component or by integrating cultural competencies into the curriculum wherever relevant. Defining a minimum of key learning objectives and ensuring that students are examined on these objectives is also important, as well as guaranteeing that teachers have good course materials and literature that reflect cultural diversity (Sörensen et al. Citation2017). Many medical schools still do not provide much leadership in conceptualizing and framing cultural diversity (Karani Citation2017; Sörensen Citation2017).

While this study has an important strength, as we were able to include a large sample of experts from diverse European countries, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, our initial list of learning objectives may have failed to include all the relevant literature on cultural competencies. Second, while we included the perspectives of care professionals, no medical students were part of the Delphi panel (Boulkedid et al. Citation2011). As evidence suggests their perspective may differ as to what is valued as important teaching competencies (Thompson et al. Citation2010). We recommend that the next step for the framework of essential competencies developed here is to validate it with medical students.

Given the growing ethnic and cultural diversity of patient populations, it is vital that future care providers are fully trained and confident in delivering culturally competent health care. This requires adequately trained medical teachers. Successful systematic implementation of the cultural competencies framework here in faculty development programs would be an important step towards equity in care.

Conclusions

This study has found consensus among experts in culture and diversity on essential teaching competencies for medical teachers with respect to teaching diversity issues and cultural competencies. This resulted in a framework of 10 competencies which can be used in training for medical teachers.

Notes on contributors

Rowan Hordijk, MSc, is a corporate anthropologist. He was affiliated to the Department of Public Health, Academic Medical Centre/University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Public Health research institute, the Netherlands, at the time of the study.

Kristin Hendrickx, MD, PhD, is a GP and professor at University of Antwerp, Belgium, Department of Primary and Interdisciplinary Care.

Katja Lanting, MSc, is a researcher at the Department of Public Health, Academic Medical Centre/University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Public Health research institute, the Netherlands.

Anne MacFarlane, Phd, is a professor of primary healthcare research at the Graduate Entry Medical School, University of Limerick, Ireland.

Maaike Muntinga, PhD, is a researcher at the department of Medical Humanities at VUmc medical center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jeanine Suurmond, PhD, is assistant professor at the Department of Public Health, Academic Medical Centre/University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Public Health research institute, the Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the C2ME partner institutions and research teams.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Berger G, Conroy S, Peerson A, Brazil V. 2014. Clinical supervisors and cultural competence. Clin Teach. 11:370–374.

- Betancourt JR. 2003. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med. 78:560–569.

- Betancourt JR, Green AR. 2010. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 85:583–585.

- Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. 2011. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 6:e20476.

- Constantinou CS, Papageorgiou A, Samoutis G, McCrorie P. 2017. Acquire, apply, and activate knowledge: A pyramid model for teaching and integrating cultural competence in medical curricula. Patient Educ Couns. [accessed 2017 Dec 30]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.12.016

- Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. 2014. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5:Cd009405.

- Humphrey-Murto S, Varpio L, Gonsalves C, Wood TJ. 2017. Using consensus group methods such as Delphi and Nominal Group in medical education research. Med Teach. 39:14–19.

- Jirwe M, Gerrish K, Keeney S, Emami A. 2009. Identifying the core components of cultural competence: findings from a Delphi study. J Clin Nurs. 18:2622–2634.

- Kai J, Spencer J, Woodward N. 2001. Wrestling with ethnic diversity: toward empowering health educators. Med Educ. 35:262–271.

- Karani R, Varpio L, May W, Horsley T, Chenault J, Miller KH, O'Brien B. 2017. Commentary: racism and bias in health professions education: how educators, faculty developers, and researchers can make a difference. Acad Med. 92:S1–S6.

- Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H. 2006. Consulting the oracle: ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 53:205–212.

- Kim-Godwin YS, Alexander JW, Felton G, Mackey MC, Kasakoff A. 2006. Prerequisites to providing culturally competent care to Mexican migrant farmworkers: a Delphi study. J Cult Divers. 13:27–33.

- Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. 2009. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 84:782–787.

- Lu PY, Tsai JC, Tseng SY. 2014. Clinical teachers' perspectives on cultural competence in medical education. Med Educ. 48:204–214.

- Martinez IL, Artze-Vega I, Wells AL, Mora JC, Gillis M. 2015. Twelve tips for teaching social determinants of health in medicine. Med Teach. 37:647–652.

- Molenaar WM, Zanting A, van Beukelen P, de Grave W, Baane JA, Bustraan JA, Engbers R, Fick TE, Jacobs JC, Vervoorn JM. 2009. A framework of teaching competencies across the medical education continuum. Med Teach. 31:390–396.

- Moynihan S, Paakkari L, Valimaa R, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. 2015. Teacher competencies in health education: results of a Delphi Study. PLoS One. 10:e0143703.

- Muntinga ME, Krajenbrink VQ, Peerdeman SM, Croiset G, Verdonk P. 2016. Toward diversity-responsive medical education: taking an intersectionality-based approach to a curriculum evaluation. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 21:541–559.

- Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CFB, Askham J, Marteau T. 1998. Consensus development methods and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 2:1–88.

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H, Guesnet F, Horne R, Jacyna S, Jadhav S, et al. 2014. Culture and health. Lancet. 384:1607–1639.

- Nazar M, Kendall K, Day L, Nazar H. 2015. Decolonising medical curricula through diversity education: lessons from students. Med Teach. 37:385–393.

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. 2000. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 320:114–116.

- Powell Sears K. 2012. Improving cultural competence education: the utility of an intersectional framework. Med Educ. 46:545–551.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. 1993. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess RG, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. London/New York: Routledge; p. 173–194.

- Rollins LK, Bradley EB, Hayden GF, Corbett EC, Heim SW, Reynolds PP. 2013. Responding to a changing nation: are faculty prepared for cross-cultural conversations and care? Fam Med. 45:728–731.

- Seeleman C, Suurmond J, Stronks K. 2009. Cultural competence: a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Med Educ. 43:229–237.

- Smedley BD, Nelson AR. 2002. Unequal treatment. confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies.

- Sörensen J, Jervelund SS, Norredam M, Kristiansen M, Krasnik A. 2017. Cultural competence in medical education: a questionnaire study of Danish medical teachers' perceptions of and preparedness to teach cultural competence. Scand J Public Health. 45:153–160.

- Sörensen J, Norredam M, Dogra N, Essink-Bot ML, Suurmond J, Krasnik A. 2017. Enhancing cultural competence in medical education. Int J Med Educ. 8:28–30.

- Suurmond J, Uiters E, de Bruijne MC, Stronks K, Essink-Bot ML. 2010. Explaining ethnic disparities in patient safety: a qualitative analysis. Am J Public Health. 100 Suppl 1:S113–S117.

- Thompson BM, Haidet P, Casanova R, Vivo RP, Gomez AG, Brown AF, Richter RA, Crandall SJ. 2010. Medical students' perceptions of their teachers' and their own cultural competency: implications for education. J Gen Intern Med. 25 Suppl 2:S91–S94.

- Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. 2014. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 14:99.

- Woolf K, Cave J, Greenhalgh T, Dacre J. 2008. Ethnic stereotypes and the underachievement of UK medical students from ethnic minorities: qualitative study. BMJ. 337:a1220.

- Woolf K, Potts HW, McManus IC. 2011. Ethnicity and academic performance in UK trained doctors and medical students: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 342:d901.