Abstract

Introduction

In competency-based medical education, direct observation (DO) of residents’ skills is scarce, notwithstanding its undisputed importance for credible feedback and assessment. A growing body of research is investigating this discrepancy. Strikingly, in this research, DO as a concrete educational activity tends to remain vague. In this study, we concretised DO of technical skills in postgraduate longitudinal training relationships.

Methods

Informed by constructivist grounded theory, we performed a focus group study among general practice residents. We asked residents about their experiences with different manifestations of DO of technical skills. A framework describing different DO patterns with their varied impact on learning and the training relationship was constructed and refined until theoretical sufficiency was reached.

Results

The dominant DO pattern was ad hoc, one-way DO. Importantly, in this pattern, various unpredictable, and sometimes unwanted, scenarios could occur. Residents hesitated to discuss unwanted scenarios with their supervisors, sometimes instead refraining from future requests for DO or even for help. Planned bi-directional DO sessions, though seldom practiced, contributed much to collaborative learning in a psychologically safe training relationship.

Discussion and conclusion

Patterns matter in DO. Residents and supervisors should be made aware of this and educated in maintaining an open dialogue on how to use DO for the benefit of learning and the training relationship.

Practice points

Direct observation (DO) comes in various patterns with various impact on residents.

Residents may experience unpredictability regarding DO patterns.

When dissatisfied after DO, residents tend not to provide critical feedback to their supervisor, but, instead, to avoid further DO.

Planned, bi-directional DO sessions appear worth promoting in residency.

Supervisors and residents should maintain an open dialogue concerning how to use various patterns of DO.

Introduction

Direct observation (DO) of residents’ skills is essential for credible feedback and assessment, and as such is a cornerstone of competency-based medical education (CBME), including postgraduate training (Holmboe et al. Citation2010; Kogan et al. Citation2017; Watling and Ginsburg Citation2019). However, direct observation takes place infrequently and both residents and supervisors have their reasons not to engage in DO. For residents, fear of assessment appears to play a role (Pelgrim et al. Citation2012; Ladonna et al. Citation2017; Schut et al. Citation2018; Brand et al. Citation2020), as well as striving for autonomy and efficiency (Madan et al. Citation2012; Watling et al. Citation2016). Moreover, as Ladonna and colleagues conclude from their interview study with residents, “the observer effect, or the unintended consequences that happen when an observer is present, may alter learners’ performance, raising questions about the authenticity of direct observation and the perceived credibility of the feedback that arises from it.” (Ladonna et al. Citation2017; Rea et al. Citation2020). Also, supervisors may not be available to observe when needed (Madan et al. Citation2012; Cheung et al. Citation2019). Supervisors, for their part, appear hesitant to initiate DO for a number of reasons, for instance lack of time, or fear of signalling mistrust to the resident (Cheung et al. Citation2019; Rietmeijer et al. Citation2018; de Jonge et al. Citation2020).

Strikingly, in this research on DO, we miss detailed descriptions of what form DO takes. This reminds us of a paper on Pattern Theory by Ellaway and Bates, in which they say: “Unfortunately, there has been a great deal of research that has focused more on analysing data generated from activities than on the activity under consideration or the context or contexts within which the activity took place” (Ellaway and Bates Citation2015). This holds true for research on DO in medical education. We are mostly not informed of the precise activity and context, e.g. who initiated DO, whether it was a planned or an ad hoc event, and what was observed. If we are to understand the dynamics of DO in residency, we should not only focus on how residents and supervisors experience it, but we first need to know what they experience, what the DO situation comprises. In other words, we are, as yet insufficiently informed on how specific residents’ experiences can be traced back to various specific forms of DO. Our aim was therefore to unravel what happens under the flag of direct observation, how this may vary and how different forms of DO may impact residents in different ways.

These considerations informed our research question:

What concrete patterns of DO, with what different meanings and effects, do residents experience?

Methods

Context

We performed our study in the setting of postgraduate general practice (GP) training at the VUmc location of the Amsterdam University Medical Centers. In Dutch GP training, residents are paired with one GP supervisor in whose practice they work for the first year of their training. In the second year, residents follow internships outside general practice. In the third and final year, residents are back in a new general practice, with another GP supervisor. These longitudinal training relationships between GP residents and supervisors are an important feature of this context when researching DO, since promoting longitudinal training relationships is increasingly advocated as a strategy to address the mechanisms that keep residents and supervisors from engaging in DO (Kogan et al. Citation2017; LaDonna et al. Citation2017). As Kogan and colleagues stated in their guidelines on direct observation of clinical skills: “Learners are more likely to engage in the process of direct observation […] when they feel their supervisor is invested in them, respects them, and cares about their growth and development” (Kogan et al. Citation2017). These conditions are more likely to occur in longer-lasting training relationships. This makes GP training a both rich and specific context for research on DO.

Residents work under nearby supervision, the supervisor being readily available. The resident and the supervisor meet for about an hour on a daily basis to discuss consultations and overarching issues. In each training year there are three instances of high-stakes assessment by the supervisor.

In this study we chose to focus on DO of technical skills only. The term ‘technical skills’ refers to physical examinations and invasive procedures, such as injections in joints or minor surgical interventions. We chose this focus because surveys show that there is a scarcity of DO of technical skills in Dutch GP training (Heiligers et al. Citation2014; Van der Velden and Batenburg Citation2011). Observation of communication skills, by contrast, is common but these skills are often observed through video recording, which has quite different dynamics. Regular DO of technical skills throughout the year is recommended by the training institute but was not formally prescribed at the time of our data collection. Unlike many other postgraduate training programmes, we do not use Mini Clinical Examinations or their equivalent systematically.

Residents follow a weekly day release programme at the training institute, in small groups of up to 14, with two group facilitators. GP supervisors are trained regularly (10 days a year) in all kinds of didactic skills, including giving feedback on residents’ communication with patients. DO of, and feedback on, residents’ technical skills, however, receive less attention in faculty development programmes. This held true for the period of our data collection.

Study design

This study is part of a larger constructivist grounded theory project, consisting of the present study with GP residents and another with GP supervisors (Rietmeijer et al. Citation2018). We chose a constructivist grounded theory approach (Watling and Lingard Citation2012; Charmaz Citation2014) since it is appropriate for exploratory research of social processes that have not previously been studied in great detail, as is the case with DO; unlike feedback, assessment, supervision and workplace learning, DO as a concrete educational activity has so far been underexplored.

We used the focus group technique to collect data. “Focus groups are a form of group interview that capitalises on communication between research participants in order to generate data” (Stalmeijer et al. Citation2014). Dutch GP training culture entails high standards of reflexivity and respect for freedom of thought and speech in the peer group. In order to optimise confidentiality, we made sure that, while the focus group sessions were held during regular group meetings, the regular group facilitators were not present. Also, we underlined the anonymity of everything that participants discussed. None of the focus group facilitators or observers were involved in the participants’ training or assessment. With these precautions, we felt that the advantages of focus groups compared to individual interviews (rich data through stories that provoke other stories) outweighed the risk of socially desirable answers.

Participants and procedure

Participant sampling was both convenience based and purposive: convenience based because we performed our focus group sessions with residents that were at the institute for their day release programme; purposive because we included groups of both first-year and third-year residents. We expected the length of experience to influence the occurrence of DO as well as residents’ feelings and thoughts about DO; more experienced residents were thought to work more independently, asking for less DO (Sagasser et al. Citation2012; Sagasser et al. Citation2015). The lead researcher (CBTR) was present at all four focus group sessions, facilitating two of them. AdW, who was not a member of our research team, facilitated the other two focus groups in order to enrich our data. Both CBTR and AdW are trained senior group facilitators, qualified to discuss sensitive subjects in groups. Both were well aware of their own assumptions about the importance of DO in workplace learning, and therefore deliberately put their ideas on hold, making sure to discuss DO situations with the participants with true curiosity, inviting all possible perspectives on the subject. DH was present at all sessions, silently observing and taking additional notes to enhance accurate data collection. All focus groups lasted approximately 75 minutes and were conducted in the second half of 2016. Participants were informed well in advance, with an emphasis on the voluntary character of the focus groups, and all signed an informed consent form before joining the focus group. Discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. To further enrich our data, shortly after the focus groups, summaries were sent to all participants, inviting them to comment and add insights. We received very few emails; those we did receive expressed approval of the reported content without further comments.

Topic list

The topic list was partly based on the literature as specified in the introduction, and partly on the authors’ experiences, and consisted of six topics, each with a number of additional questions that could help deepen the conversation. None of these questions were mandatory. The following topics were addressed:

residents’ examples of DO of technical skills

residents’ experiences with DO of technical skills

the impact of DO on learning and on the training relationship

the assumed thoughts and feelings of the supervisor concerning DO

the initiation of DO of technical skills (“Who should initiate DO?”)

the importance of DO of technical skills to the resident

The interview guide was used loosely, leaving ample room for spontaneous turns in the discussion. All thoughts and experiences related to DO were welcome. After each session, the interview guide was adjusted slightly to allow new topics of interest to be explored in greater depth. Examples of such topics were the reasons not to engage in DO, and the apparent absence of actual observation of a technical skill in many of the examples that were given when discussing DO of technical skills.

Analysis

We included a total of 31 residents in 4 focus groups. All focus group transcripts were analysed using a qualitative research software programme (Atlas.ti; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Applying the principles of constant comparative analysis (Watling and Lingard Citation2012), CBTR and DH open coded all transcripts independently, later on discussing all the codes until consensus was reached. In an early stage of this coding process, several parts of the transcripts were discussed and coded together with AHB, HdV, PWT, and FS. This was done to enhance rigour and to set standards for further coding. A codebook was developed in several rounds of discussions between CBTR, DH, AHB, HdV, PWT, and FS. Memo writing served researchers’ reflexivity; CBTR and DH articulated presuppositions in memos to discuss and reflect on them with the rest of the research team. Also, memos served to record notable contradictions and similarities as well as emerging theories on how statements and themes could be connected. Codes were merged and categorised; the final codebook contained 162 codes. Theoretical sufficiency (Charmaz Citation2014) was reached after the fourth focus group when no new patterns of DO were found and residents’ experiences shed no new light.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review committee of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Medisch Onderwijs, NVMO, protocol number 00736).

Results

In general, residents were ambivalent regarding DO: they saw benefits and necessity along with difficulties and disadvantages. We will briefly elaborate on these. We will then report on the distinct DO patterns that we found, each with its own specific benefits and disadvantages.

General pros, cons, and reservations

Many residents mentioned that being directly observed was important for patient safety and for their own learning, specifically for learning new skills and revealing blind spots:

My supervisor incidentally saw me looking into a patient’s ear, and he said, ‘Hey, what are you doing?’ And he, [laughs] he gave me some instructions on how I could just look into an ear better, but that’s something of course that is never checked. For all you know, you may keep doing this clumsily for the next 40 years. (R8, FG2)

At the same time, residents mentioned that they often felt some unease or nervousness when observed directly. Worries about the impression they made on the supervisor and the patient led them to feel judged and therefore act less naturally, both in executing technical skills as well as in connecting with the patient. Importantly, many residents felt less at ease about DO of basic skills than of new skills; because they thought they should already have mastered basic skills, it felt to them more like an assessment:

The feeling that you have to get it right, everything […], because someone’s looking at what you’re doing. But it also depends a bit; if it’s something new that I have to learn, and I’ve never done it before, then I feel free to ask everything I want and do it (the procedure) together… (R5, FG3)

Many residents reported that they asked for less DO when they became more experienced. Conversely, some felt free to ask for more DO, thereby capitalising on still being in training, after they had proven that they could work independently. An important factor in residents’ inclination to ask for DO was their perception of their supervisors’ technical and didactical qualities:

My first-year supervisor was very strong in technical skills. I really felt I could learn a lot from him, so I often asked him (for DO). My current supervisor is the opposite; I don’t think she can teach me a lot about technical skills. […] In the beginning I did ask her for DO but then I realised it wasn’t really helping me and now I ask her less… (R8, FG3)

Reservations and feelings of unease could diminish or subside as residents became more accustomed to their supervisor and to DO. By contrast, these feelings could also remain, or even worsen: feelings of frustration, loss of control, and even mistrust were reported. Importantly, this impact of DO seemed related to how DO was executed. We discerned distinct patterns in this, which we describe in the next section.

Patterns in direct observation

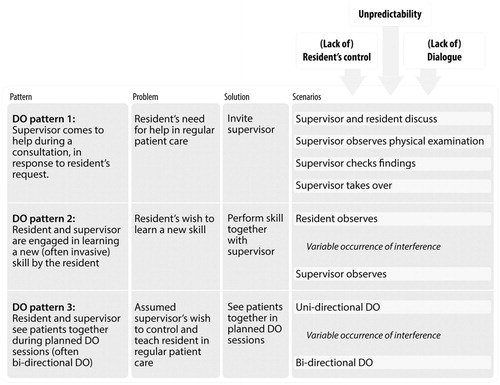

Discussing DO of technical skills with our participants raised various situations in which the resident and the supervisor were physically in the same room, engaged in patient care. DO could be the explicit purpose of the situation, but often was not. Frequently recurring patterns were (see also ):

Figure 1. Patterns of DO and related scenarios in the context of longitudinal GP training relationships; scenarios unfolded unpredictably, particularly in pattern 1.

The supervisor comes to help during a consultation, in response to a request from the resident.

The resident and the supervisor are engaged in learning a new (often invasive) skill by the resident.

The resident and supervisor see patients together during planned DO sessions.

DO pattern 1: The supervisor comes to help during a consultation, in response to the resident’s request

When discussing DO of technical skills, residents came up with many examples of situations in which they had asked the supervisor for help at some point during a consultation, mostly not explicitly requesting DO. What followed was often unpredictable, starting with the unclear waiting time that the resident and the patient had to spend together before the supervisor entered the situation. We discerned four scenarios in what happened subsequently: (a) the supervisor supports the resident in helping the patient by jointly discussing the findings, the diagnosis or the treatment plan and then leave; (b) the supervisor asks the resident to repeat the physical examination under DO; (c) the supervisor repeats the history-taking and/or the physical examination, in effect checking the resident’s findings; (d) the supervisor takes over and helps the patient herself. It is remarkable that, when discussing this DO pattern, all these scenarios came up, while only scenario b resulted in actual observation of the resident performing a technical skill.

Residents reported little control over which scenario would unfold, even though some of these scenarios could be unwanted and could have negative effects on their learning, the training relationship, and their relationship with the patient, as we see in the following quotes regarding scenarios b, c and d:

Scenario b (supervisor observes physical examination):

[…] so, the supervisor must of course verify my findings and listen to the lungs too, […] it’s useless if the supervisor observes me listening to the lungs when I’ve already done that. (R4, FG2)

Scenario c (supervisor checks findings):

That feels to me like a lack of trust; my supervisor frequently listens to the lungs after I’ve done it, and then I think, ‘Well, buddy, I’d rather see that you check other things, because I know how to do this.’ (R5, FG1)

Scenario d (supervisor takes over):

And then you sort of lose control, because you’re the resident, and he’s the GP […]. To me, it feels like losing control over the situation, and it’s hard to reclaim it […]. Then I feel more like an intern than a doctor. (R5, FG4)

Of course, afterwards you’re taken less seriously by the patient; if he (the patient) comes back another time, you’ll be seen as the intern that didn’t…(R3, FG4)

DO pattern 2: The resident and the supervisor are engaged in learning a new (often invasive) skill by the resident

In this pattern, scenarios varied from the supervisor performing and the resident watching and not actively participating, to the resident performing the procedure either under guidance or silent observation. Being observed and observing could easily alternate. Residents described that they were often caught off guard by the supervisor taking over, and felt that this could harm both their learning and the training relationship. Residents valued situations where supervisors held themselves back and left room for small personal deviations to the procedure. Some residents said they did not request DO out of fear that the supervisor would not let them carry out the procedure:

If I feel I can manage, I just do it (without DO), because otherwise I run the risk that I won’t be allowed to do it myself. (R7, FG2)

My supervisor is a perfectionist; when he observes […] he wants to intervene in order to do it (the procedure) his way…while my way is fine too [….]. So halfway he will take over a bit and in the end he will say, ‘Yeah, I should have let you do more.’ […] (R7, FG1)

DO pattern 3: The resident and supervisor see patients together during planned DO sessions

Residents stated that planned DO sessions of seeing patients together were very useful for their learning. These sessions often occurred in the initial period of getting acquainted, and were initiated by the supervisor. Residents assumed that this was to assess whether conditions of patient safety were met, and to teach by demonstrating skills. Scenarios in this pattern were less unpredictable; sometimes the practice consisted only of a resident being observed, but in most cases the resident and the supervisor alternated. With one patient, the supervisor would handle the consultation and the resident would observe, and with the next patient they would reverse these roles (bi-directional DO)

Bi-directional DO created an atmosphere of learning together: when the supervisor let the resident observe her too, this was seen as role-modelling, normalising DO, learning from each other and contributing to a climate of psychological safety. Also, residents reported that they learned a lot by watching their supervisor. Residents not only reported that a good training relationship was important in learning from DO but also, reversely, that regularly seeing patients together, observing each other, contributed to this good training climate. Moreover, residents mentioned that these planned DO sessions were indispensable for discovering blind spots, which was important to them, because they foresaw a career in which they would be working independently, without a colleague present to correct any erroneous execution of skills.

[…] if you don’t know when to ask for help, then it won’t happen; so if you build in regular moments (of DO) then I think it’ll be alright. (R1, FG1)

In most practices, it was not common to continue planned DO sessions after the first period of getting acquainted, although some residents stated that this was useful for learning and further normalised DO.

So, in the beginning I had to get used to these planned DO sessions, that someone was observing how you did things. And the longer and the more frequently you do it, the less terrible it becomes to have someone observing you. […] So you get to be more confident. (R3, FG3)

Unpredictability, lack of control, lack of dialogue

We found that residents were often taken by surprise as to which scenario would unfold when engaging in a DO situation, mostly so in pattern 1. Another finding was that residents rarely tried to exert control over how scenarios played out; instead, they adjusted to the situation as it unfolded. Moreover, when the DO situation was not satisfactory, residents often would not discuss this with their supervisor but, instead, would avoid further DO.

Well, my supervisor…he mostly does things (surgical procedures) by himself. So, when I’m present, he still does it himself. I find that a bit difficult. I haven’t discussed this with him yet, but … I will. I don’t know why he does this; I haven’t asked him. (R3, FG1)

[…] Well it’s hard to say to someone who’s been a general practitioner for over 30 years that I don’t feel she’s (laughs uneasily) […]. I would be disqualifying her […]. I don’t know what good it would do for me or for her to tell her that I don’t feel I can learn a lot from her. (R8, FG3)

However, some residents would initiate a dialogue after unsatisfactory DO experiences:

[…] So, now we have agreed that I have to have a very specific question, and she will answer that […] and then she often says, ‘Now can you manage further?’ or something like that, and then she leaves. […] Well, yeah, there had been a few incidents before I spoke up. (R1, FG4)

Discussion

The value of planned bi-directional DO for workplace learning

By discerning DO patterns, we found important distinctions between ad hoc uni-directional DO and planned bi-directional DO sessions. While the more common ad hoc uni-directional DO situations yielded little actual DO, with considerable adverse effects on the training relationships being reported, planned bi-directional DO sessions while far less common were explicitly meant for observation and learning, and tended to support psychological safety and the quality of the training relationship. These findings are consistent with earlier research on DO among GP supervisors (Rietmeijer et al. Citation2018). Our findings suggest that problems with DO, as found in a variety of previous studies on unspecified DO situations (Madan et al. Citation2012; Pelgrim et al. Citation2012; Watling et al. Citation2016; Ladonna et al. Citation2017), could be associated with the common practice of DO as ad hoc one-way events. While this dominant practice of DO may fit well in general, busy, patient care settings, one may challenge how well it aligns with the intentions underlying competency-based medical education (CBME) and workplace learning pedagogies.

Important mechanisms that explained the adverse effects of ad hoc unidirectional DO in our study were the unpredictability and the lack of agency that residents experienced. This resonates with Billet’s workplace pedagogy: learners’ engagement results from an interaction between how workplaces invite learners to experience and learn (workplace affordances), and how learners seek to do this (learners’ agency) (Billett Citation2002). As a workplace affordance that can optimise the use of DO, others have advocated longitudinal training relationships (Voyer et al. Citation2016; Kogan et al. Citation2017). Since we performed our research in a context with one-year training relationships, we can add that, within these longitudinal training relationships, planned bi-directional DO sessions are a workplace affordance that strongly supports residents’ agency and learning.

The importance of dialogue within the training relationship

Our second important finding was that many of our residents found it difficult and/or not worth the effort to provide critical feedback regarding their supervisor’s skills or behaviour during DO situations. Instead, they would sometimes avoid further DO or help seeking. This is a threat to patient safety and the efficacy of training relationships, resonating with the work of Telio and colleagues. In their interview study, they found that, when weighing the value of feedback received, residents not only made judgments about their supervisors’ skills, but, more importantly, about their supervisors’ credibility as partners in an educational alliance (Telio et al. Citation2016). In line with our results, when residents became disappointed in their supervisor, instead of taking the initiative to start a dialogue, they tended to withdraw from the relationship, no longer seeking DO and feedback (Telio Citation2016). In longitudinal training relationships of a whole year, as in our context, the cost of such withdrawals is evident.

Residents’ hesitation to enter into a dialogue with their supervisor may partly be explained by the power imbalance that is inherent in hierarchical supervisory relationships (Kilminster et al. Citation2007). Many authors have reported on the importance, and the lack, of psychological safety in hierarchical, medical education environments (Hoff et al. Citation2006; Bynum and Lindeman Citation2016; Torralba and Puder Citation2017). Another explanation for not seeking a dialogue could be that residents are afraid to offend their supervisor, or not sure that engaging in a dialogue will improve matters for them (Sheu et al. Citation2017). Our results suggest that regularly planned bi-directional DO sessions help overcome these barriers: working and learning together, getting used to DO and to each other, a supervisor who invites feedback him/herself, contributes to psychological safety and to maintaining a dialogue concerning mutual preferences in DO situations.

To conclude, dialogue appears to be a critical factor in enhancing residents’ engagement and agency in DO situations. Returning to Billett, residents’ agency in maintaining a critical dialogue will need to be stimulated by improved workplace affordances, i.e. a supervisor who actively invites feedback on his/her technical skills and on the resident’s and supervisor’s joint behaviour during DO. Regularly planned DO sessions may support this.

Implications for the practice of direct observation

Our results show that DO in GP training has great potential for learning but also bears many hazards for the resident and the training relationship. Making constructive use of DO, therefore, is far from self-evident. Medical education programmes should emphasise this and communicate that DO in residency is a challenge that requires attention. Supervisors and residents must be educated about initiating and maintaining an open dialogue that includes talking about one’s own weaknesses and preferences, both as a resident and as a supervisor, and inviting feedback, in both directions. Equally importantly, residents and supervisors must be made aware of the distinct dynamics of various DO patterns in order to reflect on how chosen DO solutions fit their needs. Moreover, in our context, supervisors and residents must be informed that regularly planned bi-directional DO sessions have great potential for learning and that these sessions should become routine in training practice. We suggest that this might also apply for education contexts in other health professions where learners work with patients under nearby supervision.

Implications for further research

Studying patterns of DO in longitudinal training relationships has revealed how the effects of DO on residents relate to what happens under the flag of DO. Studying DO patterns in other settings may reveal other patterns with an alternative impact. It will be interesting to find out whether the relevance of predictability of DO and learners’ control are universal. A further question is whether planned bi-directional DO sessions do indeed improve the use of DO in other contexts. Research is also needed on the feasibility of supervisor and resident training to prepare for the above-mentioned open critical dialogue and mutual willingness to adjust behaviours.

As another topic, patients’ experiences during DO could be a further interesting direction for research. In this study we found that the attribution of thoughts and feelings to patients during DO impacted the feelings, thoughts and sometimes behaviours of residents. This could keep residents from engaging in DO. A similar mechanism was found in a study among GP supervisors (Rietmeijer et al. Citation2018). A comparison of these attributions with the actual experiences of patients could provide new input for a better understanding of DO situations.

Limitations

We conducted our study in one GP training centre in the Netherlands. We believe that our findings may be relevant to educational contexts in other health professions with longitudinal training relationships, and perhaps also to contexts where the training relationships are of shorter duration. It is for the reader to decide whether our findings could apply to his/her particular setting. A specific limitation is that in our GP training, unlike many other post-graduate medical education (PGME) programmes, the use of mini-clinical evaluation exercises (mini-CEXs) and other structured assessment forms is limited. Our finding that residents did not ask for DO but for help might not be confirmed in a setting in which mini-CEXs are a compulsory part of training, leading residents to seek formal assessments based on DO. Frequently reported problems with the uptake of mini-CEX in many PGME programmes, however, may well relate to the same issues around the lack of residents’ control and dialogue as those revealed in our study (Ali Citation2013; Bindal et al. Citation2013; Pereira and Dean Citation2013; Driessen and Scheele Citation2013).

Conclusion

Through discussing DO of technical skills situations with GP residents, we found three different DO patterns and, within these patterns, a number of different scenarios. The DO pattern/scenario that took place was decisive for the actual occurrence of DO, its yield for residents’ learning, and its impact on training relationships. Strikingly, residents experienced unpredictability and a lack of agency concerning which pattern/scenario would unfold when engaging in DO. Also, when dissatisfied, residents seldom provided critical feedback regarding their supervisor’s skills or behaviour during DO situations. Instead, they would sometimes avoid further DO or seeking help. Our findings indicate that training programmes should make supervisors and residents aware of the advantages and risks of the various DO patterns and scenarios. Moreover, supervisors and residents should be educated in maintaining an open dialogue, including mutual feedback, concerning how to use DO, both for the benefit of the training relationship and residents’ learning. This dialogue will probably be supported by supplementing the currently prevalent ad hoc one-way DO occasions with planned bi-directional DO sessions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the residents who participated in this study. Anne de Wit, psychologist at the department of General Practice and Elderly Care Medicine at Amsterdam University Medical Center, location VUmc, Amsterdam, facilitated two of the focus groups. Marilyn Hedges provided feedback on English grammar and style.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chris B. T. Rietmeijer

Chris B. T. Rietmeijer, MD, is a general practitioner and curriculum director at the General Practice training center of the Amsterdam University Medical centers, location Vumc. He is currently working on his PhD research concerning direct observation in GP residency.

Annette H. Blankenstein

Annette H. Blankenstein, MD, PhD, general practitioner, is senior researcher at Amsterdam University Medical Centers, location Vumc, Department of General Practice. She performed research among GP residents on using Patient Feedback, applying Palliative Care, and managing Medically Unexplained Symptoms. Until 2021 she was head of the general practice training center at Vumc.

Daniëlle Huisman

Danielle Huisman, MSc in Clinical Neuropsychology, is currently doing a PhD in Health Psychology at King’s College London, UK. Danielle previously worked as a research assistant at Amsterdam UMC, The Netherlands, on projects concerning medically unexplained physical symptoms, cardiovascular risk management, and competency-based medical education in primary care.

Henriëtte E. van der Horst

Henriëtte E. van der Horst, MD, PhD, is a professor of general practice and was head of the Department of General Practice and Elderly Care Medicine at VU medical centre until 2019. Currently, she is chair of the division Primary Care, Public Health and Methodology of Amsterdam University Medical Centres.

Anneke W. M. Kramer

Anneke W. M. Kramer, MD, PhD, is a general practitioner and professor at the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), focusing on educational research in workplace learning.

Henk de Vries

Hendrik de Vries, MD, PhD, is a retired professor of Family Medicine. He developed the curriculum of clinical reasoning of the bachelor and masters medical training at Amsterdam UMC (location VUmc). He now coaches educators of trainees in Family Medicine.

Fedde Scheele

Fedde Scheele, MD, PhD, is a professor in Health Systems Innovation and Education at the departments of Science and Medicine of the VU University of Amsterdam. He practices gynaecology at the OLVG Teaching Hospital and is Dean of the OLVG Health School. He is involved in National and International projects to improve education for health professionals.

Pim W. Teunissen

Pim W. Teunissen, MD, PhD, is a professor of workplace learning in healthcare. He is director of the School of Health Professions Education at Maastricht University and also works as a gynecologist specialised in high-care obstetrics at the Maastricht University Medical Center. He chairs the redesign committee for the national residency program of the Dutch Society for Obstetrics and Gynecology.

References

- Ali JM. 2013. Getting lost in translation? Workplace based assessments in surgical training. Surgeon. 11(5):286–289.

- Billett S. 2002. Toward a workplace pedagogy: Guidance, participation, and engagement. Adult Education Quarterly. 53(1):27–43.

- Bindal N, Goodyear H, Bindal T, Wall D. 2013. DOPS assessment: a study to evaluate the experience and opinions of trainees and assessors. Med Teach. 35(6):e1230–e1234.

- Brand PL, Jaarsma ADC, van der Vleuten CP. 2021. Driving lesson or driving test? Perspect Medical Educ. 10(1):50–56.

- Bynum WE, Lindeman B. 2016. Caught in the middle: a resident perspective on influences from the learning environment that perpetuate mistreatment. Acad Med. 91(3):301–304.

- Charmaz K. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications; p. 1–21.

- Cheung WJ, Patey AM, Frank JR, Mackay M, Boet S. 2019. Barriers and enablers to direct observation of trainees' clinical performance: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Acad Med. 94(1):101–114.

- de Jonge LP, Mesters I, Govaerts MJ, Timmerman AA, Muris JW, Kramer AW, van der Vleuten CP. 2020. Supervisors’ intention to observe clinical task performance: an exploratory study using the theory of planned behaviour during postgraduate medical training. BMC Med Educ. 20:1–10.

- Driessen E, Scheele F. 2013. What is wrong with assessment in postgraduate training? Lessons from clinical practice and educational research. Med Teach. 35(7):569–574.

- Ellaway RH, Bates J. 2015. Exploring patterns and pattern languages of medical education. Med Educ. 49(12):1189–1196.

- Heiligers P, van der Velde L, Batenburg R. 2014. De opleiding tot huisarts opnieuw beoordeeld in 2014. Een onderzoek onder huisartsen in opleiding en alumni. http://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/Rapport-kwaliteit-huisartsenopleiding-2014.pdf.

- Hoff TJ, Pohl H, Bartfield J. 2006. Teaching but not learning: how medical residency programs handle errors. J Organiz Behav. 27(7):869–896.

- Holmboe ES, Sherbino J, Long DM, Swing SR, Frank JR. 2010. The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 32(8):676–682.

- Kilminster S, Cottrell D, Grant J, Jolly B. 2007. AMEE guide No. 27: effective educational and clinical supervision. Med Teach. 29(1):2–19.

- Kogan JR, Hatala R, Hauer KE, Holmboe E. 2017. Guidelines: The do's, don'ts and don't knows of direct observation of clinical skills in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 6(5):286–305.

- LaDonna KA, Hatala R, Lingard L, Voyer S, Watling C. 2017. Staging a performance: learners' perceptions about direct observation during residency. Med Educ. 51(5):498–510.

- Madan R, Conn D, Dubo E, Voore P, Wiesenfeld L. 2012. The enablers and barriers to the use of direct observation of trainee clinical skills by supervising faculty in a psychiatry residency program. Can J Psychiatry. 57(4):269–272.

- Pelgrim EA, Kramer AW, Mokkink HG, van der Vleuten CP. 2012. The process of feedback in workplace-based assessment: organisation, delivery, continuity. Med Educ. 46(6):604–612.

- Pereira EA, Dean BJ. 2013. British surgeons' experiences of a mandatory online workplace based assessment portfolio resurveyed three years on. J Surg Educ. 70(1):59–67.

- Rea J, Stephenson C, Leasure E, Vaa B, Halvorsen A, Huber J, Bonnes S, Hafdahl L, Post J, Wingo M, et al. 2020. Perceptions of scheduled vs. unscheduled directly observed visits in an internal medicine residency outpatient clinic. BMC Med Educ. 20(1):64.

- Rietmeijer CBT, Huisman D, Blankenstein AH, de Vries H, Scheele F, Kramer AWM, Teunissen PW. 2018. Patterns of direct observation and their impact during residency: general practice supervisors' views. Med Educ. 52(9):981–991.

- Sagasser MH, Kramer AW, van der Vleuten CP. 2012. How do postgraduate GP trainees regulate their learning and what helps and hinders them? A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 12:67.

- Sagasser MH, Kramer AW, van Weel C, van der Vleuten CP. 2015. GP supervisors' experience in supporting self-regulated learning: a balancing act. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 20(3):727–744.

- Schut S, Driessen E, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten C, Heeneman S. 2018. Stakes in the eye of the beholder: an international study of learners' perceptions within programmatic assessment. Med Educ. 52(6):654–663.

- Sheu L, Kogan JR, Hauer KE. 2017. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 92(9):1320–1327.

- Stalmeijer RE, Mcnaughton N, Van Mook WN. 2014. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE guide No. 91. Med Teach. 36(11):923–939.

- Telio S, Regehr G, Ajjawi R. 2016. Feedback and the educational alliance: examining credibility judgements and their consequences. Med Educ. 50(9):933–942.

- Torralba KD, Puder D. 2017. Psychological safety among learners: when connection is more than just communication. J Grad Med Educ. 9(4):538–539.

- Van der Velden L, Batenburg RS. 2011. De opleiding tot huisarts opnieuw beoordeeld: een onderzoek onder huisartsen in opleiding en alumni. http://www.narcis.nl/publication/RecordID/publicat%3A1002099.

- Voyer S, Cuncic C, Butler DL, MacNeil K, Watling C, Hatala R. 2016. Investigating conditions for meaningful feedback in the context of an evidence-based feedback programme. Med Educ. 50(9):943–954.

- Watling C, LaDonna KA, Lingard L, Voyer S, Hatala R. 2016 .'Sometimes the work just needs to be done': socio-cultural influences on direct observation in medical training. Med Educ. 50(10):1054–1064.

- Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. 2019. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ. 53(1):76–85.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. 2012. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE guide No. 70. Med Teach. 34(10):850–861.