Abstract

For this AMEE Guide, we explore the process and application of an evolved tool known as the audio diary. Diaries are a type of qualitative method that has long been advocated for in healthcare education practice and research. However, this tool has been typically underestimated as an approach to capturing how individuals’ experiences change over time. In particular, this longitudinal method can nurture a stronger partnership between the researcher and participant, which can empower participants to share their reflections as they make sense of their identities and experiences. There is a wider issue concerning how to use and implement audio diaries in medical education research, this guide outlines a foundational process by which all levels of researchers can use to ensure the purpose, application and use of the audio diary tool is done with quality, rigour and ethics in mind. The processes presented are not a prescriptive approach to utilising audio diaries as a longitudinal method. This AMEE Guide serves as an opportunity for researchers and educators to consult this resource in making decisions to decide whether the audio diary tool is fit for their research and/or educational purpose and how audio diaries can be implemented in health profession education projects. This guide discusses and addresses some of the ethical, operational and contextual considerations that can arise from using audio diaries as a tool for longitudinal data collection, critical reflection, or understanding professionalism.

What are audio-diaries?

Audio diaries are a qualitative longitudinal method within the social sciences that enable researchers to explore participants’ lived experiences in-action and in-situ within a specific context over time (Monrouxe Citation2009). They stem from a suite of qualitative tools that seek to capture observations, interviews, documents and audio-visual data (Creswell Citation2007). The audio diary itself derives from the use of written diaries in the social sciences, which have historically allowed participants to write down their thoughts, actions and emotions (Worth Citation2009). Audio diaries can be considered an evolved form of the written diary method and are used in disparate fields spanning from health to cognitive psychology and beyond (e.g. Metatla et al. Citation2015; Pilbeam et al. Citation2016). As technology evolves, this has widened opportunities to implement diary methods to explore human thoughts, feelings and perceptions. The audio diary is considered a versatile ethnomethodological tool, which can be defined as an approach that uses natural talk to co-constructing knowledge and realities (McCreaddie and Payne Citation2010). The audio diaries build on similar tools such as ethnographic and longitudinal field notes, and research memos which have been utilised in disparate fields across the social sciences (e.g. Stevenson Citation2016). The audio diary tool has also been implemented as teaching and educational resources, to nurture reflective practice (e.g. Káplár-Kodácsy and Dorner Citation2020) and clinical professionalism (e.g. Neve et al. Citation2017). For this guide, the author presents an approach to audio-diaries in the context of educational research. However, it also provides some recommendations for the use of the audio-diary method for educational and teaching purposes.

Practice points

Audio diaries are a tool used in longitudinal qualitative research to explore how people’s experiences, thoughts and conditions interplay and change over time.

Ensuring the design of the audio diary study has strong theoretical and operational foundations for monitoring participants’ experience of their audio diary journey.

The audio diary can empower participants to make sense of their identities and lived experiences in medical education.

The researcher and/or educator performs a facilitative role in the longitudinal audio diary study to empower participants to use the audio diaries in a way that suits them, whilst supporting and prompting in line with the scope of the researcher’s objectives.

Analysing audio diary data through a longitudinal lens explicitly enables the researcher to explore how time has changed the participants’ lived experiences.

Audio diaries enable participants to emphasise the performative parts of their identities through their thoughts, feelings, behaviours and experiences, by engaging in self-talk, whilst mitigating some of the ethical concerns associated with video diaries and allowing a deeper exploration of the data through audio and voice (Kenten Citation2010). There is a consensus across the cited literature that this tool can explore multiple social themes through the lens of time and is considered a happy medium between the written and the visual approaches to diary tools. The audio diary enables participants to talk through their experiences and engage in a reflective dialogue related to their lived experiences. Such reflective learning and practice are considered essential to the development and professionalism of future healthcare practitioners (GMC Citation2009; Bulman and Schutz Citation2013). Empowering learners to make meaning of, integrate and consolidate their knowledge and experiences is an important skill which can be applied to different contexts in their healthcare practice (Sandars Citation2009). An audio diary is a pragmatic tool that nurtures reflection-in and -on action in healthcare trainees (Munby Citation1989), as it offers a ‘hands-free method’ where learners may make sense of their experiences in real-time situations (Williamson et al. Citation2015).

There is limited research exploring the use of audio diaries in medical and the health professions education (HPE) and this method is arguably undervalued in exploring conceptual themes like identity formation and development (Monrouxe Citation2009). Crozier and Cassell (Citation2016) found that audio diaries can effectively capture cognitive processes and provide opportunities for reflection about experiences. They also reported that audio diaries, when combined with interviews, provided participants with an accessible mean to verbalise, and share sensitive information. Similarly, audio diaries were perceived to be a convenient and easy to use tool to collect data compared to written diaries, particularly for those participants less inclined to report their experiences or thoughts in a written form (Brauer Citation2013; Crozier and Cassell Citation2016). It is noteworthy here to say that the audio diary holds a great deal of versatility, and this AMEE guide seeks to provide a foundational model for researchers to make informed decisions about its use, adaptations and application in educational research and practice. Further, clinical teachers can use audio diaries to nurture reflective practice and as a novel mode to teach professionalism in the workplace (e.g. Birden et al. Citation2013).

Why use the audio-diaries?

The purpose for using any kind of diary tool is for the researcher, educator and participant to engage in a meaningful and professional dialogue about the individual’s lived experiences, thoughts, feelings and behaviours (e.g. Gadassi et al. Citation2016; Lester Citation2017). There is a plethora of effective qualitative data collection methods such as observations, interviews and focus groups that capture data at specific time-points (i.e. Smithson Citation2000). Written diaries are also effective, yet participants’ ability and motivations to accurately write their entries may limit their use (Välimäki et al. Citation2007). Although these qualitative methods have merits in their own right, the audio diary enables the researcher to see changes in an individual’s entries over time. This mode of qualitative data gathering also allows the individual to record entries at any time and place, therefore enhancing the utility and usability of the diary tool (i.e. a tablet, notebook or computer to write entries).

Due to technological advancements, diaries have evolved to incorporate audio and sometimes video elements to diarizing in medical education research (Bates Citation2013; Williamson et al. Citation2015; Thompson et al. Citation2016; La Caze Citation2017). This has meant that the diary tool has evolved to become more accessible and easier to use in most environments. Audio diaries are unique in that they allow participants to break the rules of writing and literacy and permits them to share a rolling stream of consciousness that sheds light on the unique experiences and stories of the individual. Audio diaries are a unique longitudinal tool in that they capture naturalistic and non-verbal data, which are critical to understanding how experiences, feelings and consciousness change over time (Hislop et al. Citation2005; Crozier and Cassell Citation2016). The versatility of the audio diary research method means it can be employed across multiple disciplines that allow the facilitator and participant to co-construct and share experiences in action under specific conditions over a longer period of time (Monrouxe Citation2009). Audio diaries stem from the use of written diaries in the social sciences (Worth Citation2009). Despite drives to use audio diaries, this tool is still undervalued and underestimated in exploring lived experiences, identity formation and cognition (Crozier and Cassell Citation2016; Milligan and Bartlett Citation2019).

Research about the audio diary as a research method has shown how healthcare trainees’ professionalism and identity formation is enacted by talking through their lived experiences (e.g. Crozier and Cassell Citation2016). The audio diary as a tool can be underpinned by disparate methodological theories from narrative inquiry (e.g. Collett et al. Citation2017) through to ethnography (Jeffrey Citation2016). Utilising audio diaries can help participants overcome challenges in reflective practice (e.g. clinical reasoning) and cognitive (e.g. concept formation) and academic (e.g. stress management) skills development (Muir and Law Citation2013). The theoretical positioning of audio diaries can be noted to be embedded within a relativist ontology, which asserts that multiple realities can be perceived and conceived in the individual’s mind (Rees and Monrouxe Citation2010). However, when the audio diary is utilised in educational research and/or practice, it can be rooted within a social constructionist perspective in that the audio diary becomes a subject of focus and an area for critical reflection about making sense of experiences, perceptions, thoughts and emotions with support from a research and/or educational facilitator (Hargreaves Citation2016). Qualitative research has reported the advantages of using audio diaries as a rich platform to explore themes and issues related to identity formation (e.g. Monrouxe Citation2009) and intersectionality (e.g. Verma Citation2020). This guide does aim to sustain these arguments and highlights a proposed process for using audio diaries in educational research and practices. The process section below deconstructs the audio diary process to enable the reader to consider how an audio diary study could be implemented as a research and, in some instances, as an educational tool.

The role of the researcher, participant and educator in the use of audio-diaries

Audio diaries require a thoughtful and trustworthy relationship between the researcher and participant to share and shape the understanding of their realities, experiences and identities over time (Balmer and Richards Citation2017; Gordon et al. Citation2017). The relationship between the researcher and participant is critical to manage during the audio diary process, and prolonged engagement and interaction between researcher and participant can help mitigate emerging ethical issues. This prolonged engagement fits well within a social constructionist epistemology, which means that the facilitator and participant are co-constructing their experiences over time and can mean that participants are more actively involved in the research process (Harvey Citation2017). The researcher in an audio diary study is usually beholden to the participant’s way of engaging or sometimes not engaging enough with the tool, resulting in the participant becoming an empowered agent of the research, rather than a subject for exploration (Dudgeon et al. Citation2017). Educators may harness the use of audio diaries, collecting longitudinal information in real time about specific aspects of the educational process across different contexts. Despite research on the use of audio diaries to explore social interaction between physicians and learners in the workplace setting and on students’ preparedness and experiences during key transitions in their roles (e.g. Brennan et al. Citation2010; Van der Zwet et al. Citation2014), there is still limited evidence on how educators may further utilise or integrate audio diaries into their educational practices.

How to use audio-diaries?

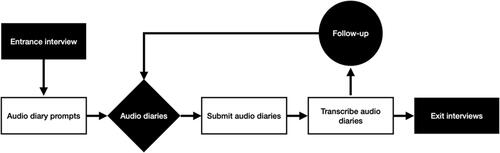

The audio diary method requires an individual to coordinate and ensure there is robust governance and diligence to oversee the audio diary process, particularly if the research tool is implemented for a multi-site study (i.e. in more than two different locations). and the steps below depicts the process and outlines the flow for the use of the audio diary method as a research tool.

The researcher performs an entrance interview with one or more participants to sensitize them to the scope and process of the research study.

Participants receive prompts to record and submit their audio diaries.

The researcher transcribes and returns transcripts to participants to check diary entries for accuracy.

Participants submit the minimum number of audio diaries needed for the research project.

The researcher invites the participant to an exit interview to inquire about participants’ experiences about the use of audio diaries and to provide them with an opportunity for further clarification of the data collected.

If you are a clinical educator, you could adapt this model to foster reflective practice. For example, the educator may use the entrance interview to set learning objectives about a session or a clinical encounter, then provide learners with prompts to record in their audio diaries meaningful reflections and thoughts about the learning process. Finally, the exit interviews/focus groups might serve as a debriefing and a discussion about the submitted audio diary entries and narrated experiences.

The following sections details components of the audio diary process in more detail.

Before starting

Prior to commencing the use of audio diaries, we anticipate the researcher will be discussing issues pertaining to the core questions, ethical considerations, implementation and analysis of audio diaries. At this point, it would be ideal for the researcher to refer to best practices in conducting research and qualitative research from AMEE Guides 56 (Ringsted et al. Citation2011) and 80 (Reeves et al., Citation2013), and consider the theoretical underpinnings of the audio diary study to inform how you collect and make sense of the data (Bunniss and Kelly Citation2010).

Entrance interviews/focus groups

The starting interviews/focus groups are critical to socializing critical healthcare education and professional concepts, questions and scope with participants. It is an opportunity for participants to begin thinking about their experiences and practice their reflective dialogue whilst becoming familiar with the research scope and information. This enables participants and the researcher to sensitise all parties to the audio diary process and troubleshoot any questions participants have before they embark on their audio diary journey. The entrance interviews should follow a semi-structured format allowing for the interviewer and participants to share some of their thoughts and feelings outside of the specific interview questions. This allows the interviewer to perform a facilitative role and prompt participants in directions pertinent to the scope of the research study (Rabionet Citation2009; refer to AMEE Guide 91 by Stalmeijer et al. Citation2014). However, this sometimes means that participants may leave gaps in their experiences that could be important to the research question, and we recommend including some interview prompts to help the researcher and participant explore their experiences in a little more detail (Baumbusch Citation2010).

Like most interviews/focus groups, the researcher should ensure that the questions are not leading and that they follow a systematic approach to minimise collecting heterogeneous data. Working in a research team or with critical peers can help ensure that developing an interview schedule undergoes critique to enable a consistent approach. The entrance interviews enable the research to ask more operational questions about the logistics of participating in an audio diary study. For example, researchers can find out how the participants may prefer to record their audio diaries (e.g. either by smartphone or Dictaphone). Participants may typically use their smartphones to record and submit their diary entries, however, there may be individuals that require a Dictaphone to record their experiences, particularly if they are in areas where digital access is limited (i.e. remote and rural areas). It is also possible to combine the audio diary with other qualitative data collection methods (e.g. observations) to take note of additional socio-cultural aspects of the audio diary journey.

Audio diary prompts

The audio diary prompts should be similar to the entrance interviews in that they provide participants with a semi-structured guide to supporting participants in recording their reflections. The audio diary tool should be directive in nature and avoid a stringent structured approach, to allow some flexibility for participants to explore their thoughts and experiences (Boud and Walker Citation1998; Kolb Citation2014). Participants should be provided with an audio diary prompt sheet, which may include a list of broad research related questions for the participant to reflect upon in their recordings. Prompts can be used to help draw a participant’s attention to the research objectives. As the researcher is not explicitly present during each recording, the prompts can provide participants with self-directed reference points when recording their audio diaries. In the teaching setting, prompts could be aligned with learning objectives to help ensure audio diary users are reflecting on themes pertinent to their professional development or to other learning areas.

Audio diaries: submitting, transcribing and following up

Audio diaries can be submitted in a way that suits the participant’s daily and weekly routines. For example, some participants may record and submit diaries once a week, others may record diaries daily or monthly, the author advises capturing a minimum of 8–12 audio diaries per participant to ensure there is enough data captured across a significant amount of time. The researcher should try to establish in the entrance interview a schedule or timetable for recording and submitting audio diaries entries, so that participants are encouraged to try and record their diaries regularly. We suggest a weekly diary is sufficient over a minimum three-month period, however, this could be adjusted to meet the needs of the research project. During the audio diary phase, regular recordings might not always be possible (i.e. difficulties in time management, student exam stress, placements in remote and rural areas). This requires the researcher to remain flexible to accommodate and support participants’ needs across different contexts (e.g. Graziotti et al. Citation2012).

While participants record their experiences and submit them to the facilitator, researchers may wish to transcribe the participants’ audio diaries and send them a copy of the transcript. This can be particularly useful for healthcare students and professionals engaging in their reflective practice assessments and/or continuing professional development (Westberg Citation2001; Wald et al. Citation2012). Sharing the data with participants can enhance their engagement with recording audio diary entries and can help keep an open line of communication between researcher and participant. Returning audio diary transcripts to the participant can ensure the researcher is capturing participants’ data accurately.

The benefit of the audio diary method is that participants can engage in recording their reflections using audio diaries in a way that suits their tone, voice and style. Each participant talks into the audio diary in different ways, collecting different types of information; for example, there may be participants that share stories of their experiences (e.g. Sandars et al. Citation2008) or participants may talk about the schedule of their professional activities that day (e.g. Snaith et al. Citation2016). The quality of audio diary data may vary from one person to another, which allows to gather rich and meaningful data about participants’ reflective dialogues.

Exit interviews/focus groups after completion of audio diaries

Participants should be invited to an exit interview/focus groups after they have completed the minimum required audio diary submissions or requested to end their participation in the research project. The exit process is a unique opportunity for the participants and researcher to engage in a debrief following their experience with the use of audio diaries (Choy Citation2014). It allows participants to review their data whilst providing researchers with an opportunity to clarify any areas of doubt or uncertainty. Like the entrance interviews and audio diary prompts, these final interviews follow a semi-structured schedule. The exit interview enables the interviewer to follow-up and clarifies any issues arising from transcribing the participants’ audio diaries (i.e. inaudible words, clarifying meanings of colloquial words/phrases and professional jargon). The exit interview provides a platform for participants to provide feedback about using the audio diary process in a research project and for improving the method, its implementation and application for future studies (e.g. Thomas Citation2017). Although it is useful to engage the same participants in both opening and closing interviews, this may not always be possible throughout the research study. Further, a change in the researcher’s team may influence the relationships built between the interviewer and participant. This is a limitation to be mindful of, when planning an audio-diary study.

Similarly, to entrance interviews, teachers may use this part of the audio diary process (exit interviews) to engage in peer-assessment and/or in a debriefing session about the process and value of the educational experience, whilst assessing the achievement of previously determined learning objectives.

Analyzing audio diaries

Interpreting and making sense of audio diary data can be overwhelming as you are presented with data that spans across multiple participants’ longitudinal experiences and cross-sectional data used to capture overarching themes and issues across the data (Sheard and Marsh Citation2019). Organising the data is key to ensure that you can find the audio diaries for each participant with ease and exploring each participants’ journey individually may allow for a meaningful synthesis of all participants’ experiences (Herber and Barroso Citation2019). The critical aspect to analysing audio diary data is to embrace time as part of the analysis and to consider how participants’ experiences, thoughts, and feelings may or may not change over time. The notion of time enables the researcher to understand what and how themes and issues in participants’ recordings can change from one audio diary to another and can be reflected in the research questions. For example, accounting for time in analyses could be explored through a framework analysis to identify how themes and environments intersect and change over time (e.g. Crozier and Cassell Citation2016), or it could be accomplished in the form of a longitudinal case study exploring the individual’s journey holistically (e.g. Grimell Citation2017).

The unique aspect to audio-diaries is the ability to capture non-verbal audible interaction, which includes anything from laughter, pauses, coughing and silences. Such non-verbal cues add another layer to qualitative analysis and can be used to unpack how participants use language to convey their experiences and identities (Warmington Citation2019). However, visual cues such as participants’ facial and bodily expressions cannot be explored through this tool and may present a challenge, depending on the researcher or educators’ needs. Researchers reading this guide might find some solace in doing first a cross-sectional analysis to explore all qualitative data collected from the entrance interviews, audio diaries and exit interviews (Gale et al. Citation2013). Then, by integrating time (or temporality) into the analysis, the researcher can interrogate each individual’s audio diary journey, and gain insight into how their individual experience has changed over time in relation to the overarching themes identified in the cross-sectional analysis. There are other examples of integrating time into the longitudinal qualitative analysis, including the use of an adapted framework analysis approach (Ward et al. Citation2019), using interpretative phenomenological analysis (Biggerstaff and Thompson Citation2008; McCoy Citation2017) or even sociolinguistic analysis (Verma Citation2020).

Challenges

A challenge for using the audio diary method over time concerns participants’ retention and engagement, which is a common challenge across most types of longitudinal research methods in health professions education research (Teague et al. Citation2018). It’s important to note that the participant does have to be motivated to engage, record and submit audio diaries regularly. The researcher may need to nudge and notify participants to keep up with their recordings or explore whether there are any issues in the participant’s continuing engagement. Yet, such conversations can deepen the relationship between the researcher and the participant. Issues concerning changes in participants’ lives, motivation and environments can contribute to their attrition from a research study and are noted in other forms of longitudinal research (Harvey Citation2015).

The researcher conducting an audio diary-based study over multiple sites is faced with the challenge of arranging, tracking and following up on participants’ exit interviews, and working in a collaborative team can help mitigate the issues this poses. Although there is an argument to advocate for social media to engage participants (e.g. Mychasiuk and Benzies Citation2012), other studies have noted that entrance interviews and incentives are important and may enable continued engagement with participants during the study (Taylor Citation2009).

Another challenge may relate to the technology of recording and submitting audio diaries. Participants that use smartphones may have difficulties sending large audio recording data via email due to file size limitations, therefore creating a challenge for a regular and continuous submission of audio diaries data. Additionally, audio diaries are often recorded at different time points, rather than continuously over time, therefore the researcher may find it challenging to decipher whether any significant events or interactions have been missed or lost. With regards to technology, the use of mobile applications that enable participants to record and send compressed audio files, may be worth exploring. However, before using any mobile applications to collect audio diary data, it is important to ensure secure data storage. The use of Dictaphone to recodn and collect data, may create issues in that the participant may not be able to submit their entries until they either upload them and send the audio files electronically, or they return the Dictaphone to the researcher. Such close and prolonged monitoring of participants’ entries during the audio diary study can be challenging and time consuming.

Ethical considerations

There are numerous ethical considerations to deliberate that are unique to the audio diary method, in addition to best practices in conducting ethical research (Ramana et al. Citation2013; Anderson and Munoz Proto Citation2016). These are related to audio diaries inadvertently capturing audio data that is not from the participants. Further, having researchers away from participants during audio diary recording may create challenges to monitoring potential participant’s distress, with the potential for audio diary to unknowingly affect or shape participants’ behaviour (Williamson et al. Citation2015). Researchers should consider how to mitigate these unique ethical risks when preparing an audio diary study for ethical approval. We recommend ensuring full transparency and awareness of the direct and indirect risks of the audio diary method within the context in which they are being implemented.

Final reflections

As a result of presenting audio diaries in this AMEE guide, the author has described a foundational framework for developing, designing and implementing audio diaries in a research and/or educational project. Although this guide focuses on the pragmatic and process-oriented aspects of using audio diaries, there is a deeper discussion concerning the theoretical underpinnings of using audio diaries in healthcare education practice, and further pragmatic ethical considerations about data security and management. These are topics that are discussed in much more detail in other literature (e.g. Monrouxe Citation2009). The reader is encouraged to be mindful of how these theoretical underpinnings intersect as they embark on an audio diary journey. As the audio diary tool is implemented in different contexts, the author acknowledges that there might be additional approaches to using audio diaries. However, we hope this guide can serve as a strong foundation for researchers and educators who are interested in implementing audio diaries in their future research and educational endeavours.

From consulting this guide, we anticipate that interested health professions educators and researchers can appreciate that longitudinal methods using audio diaries require diligence and careful planning, in order to enhance retention of participants and achieve data collection goals. We hope that the implementation of audio diaries, as recommended in this guide, can help ensure the necessary quality and rigor of audio diary research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arun Verma

Dr. Arun Verma completed his PhD exploring intersecting identities in gendered workplace learning environments, at the Centre for Medical Education (University of Dundee). He has since gone on to implement innovative national and global programmes of applied research and evaluation in government and the third sector. He is a Senior Adviser at a large charity, he is Tutor for the University of Dundee supporting academic examination and supervision within the Centre for Medical Education.

References

- Anderson SM, Munoz Proto C. 2016. Ethical requirements and responsibilities in video methodologies: considering confidentiality and representation in social justice research. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 10(7):377–389.

- Balmer DF, Richards BF. 2017. Longitudinal qualitative research in medical education. Perspect Med Educ. 6(5):306–310.

- Bates C. 2013. Video diaries: audio-visual research methods and the elusive body. Vis Stud. 28(1):29–37.

- Baumbusch J. 2010. Semi-structured interviewing in practice-close research. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 15(3):255–258.

- Biggerstaff D, Thompson AR. 2008. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a qualitative methodology of choice in healthcare research. Qual Res Psychol. 5(3):214–224.

- Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. 2013. Teaching professionalism in medical education: A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 35(7):e1252–e1266.

- Boud D, Walker D. 1998. Promoting reflection in professional courses: the challenge of context. Stud High Educ. 23(2):191–206.

- Brauer G. 2013. The challenge of reflective writing as a chance for deep learning. On Reflection. (25):19–27.

- Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, Collett T, de Bere SR. 2010. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Med Educ. 44(5):449–458.

- Bulman C, Schutz S, editors. 2013. Reflective practice in nursing. 5th ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bunniss S, Kelly DR. 2010. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 44(4):358–366.

- Choy LT. 2014. The strengths and weaknesses of research methodology: comparison and complimentary between qualitative and quantitative approaches. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 19(4):99–104.

- Collett T, Neve H, Stephen N. 2017. Using audio diaries to identify threshold concepts in 'softer' disciplines: a focus on medical education', Practice and Evidence of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Special Issue: Threshold Concepts and Conceptual Difficulty. 12(2) :99–117. ISSN 1750-8428.

- Creswell JW. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Crozier SE, Cassell CM. 2016. Methodological considerations in the use of audio diaries in work psychology: adding to the qualitative toolkit. J Occup Organ Psychol. 89(2):396–419.

- Dudgeon P, Scrine C, Cox A, Walker R. 2017. Facilitating empowerment and self-determination through participatory action research: findings from the National Empowerment project. Int J Qual Methods. 16(1):160940691769951.

- Gadassi R, Bar-Nahum LE, Newhouse S, Anderson R, Heiman JR, Rafaeli E, Janssen E. 2016. Perceived partner responsiveness mediates the association between sexual and marital satisfaction: a daily diary study in newlywed couples. Arch Sex Behav. 45(1):109–120.

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. 2013. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 13:117.

- GMC. 2009. General Medical Council Tomorrow’s Doctors: recommendations on undergraduate medical education. London: General Medical Council.

- Gordon L, Jindal-Snape D, Morrison J, Muldoon J, Needham G, Siebert S, Rees C. 2017. Multiple and multidimensional transitions from trainee to trained doctor: a qualitative longitudinal study in the UK. BMJ open. 7(11):e018583.

- Graziotti AL, Hammond J, Messinger DS, Bann CM, Miller-Loncar C, Twomey JE, Bursi C, Woldt E, Nelson JA, Fleischmann D. 2012. Maintaining participation and momentum in longitudinal research involving high-risk families. J Nurs Scholarsh. 44(2):120–126.

- Grimell J. 2017. A service member’s self in transition: a longitudinal case study analysis. J Constr Psychol. 30(3):255–269.

- Hargreaves K. 2016. Reflection in medical education. J Univ Teach Learn Pract. 13(2):6.

- Harvey C. 2017. The Intricate process of psychoanalytic research: encountering the intersubjective experience of the researcher–participant relationship. Br J Psychot. 33(3):312–327.

- Harvey L. 2015. Beyond member-checking: a dialogic approach to the research interview. Int J Res Method Edu. 38(1):23–38.

- Herber OR, Barroso J. 2019. Lessons learned from applying Sandelowski and Barroso’s approach for synthesising qualitative research. Qual Res. 2019:1468794119862440.

- Hislop J, Arber S, Meadows R, Venn S. 2005. Narratives of the night: the use of audio diaries in researching sleep. Sociol Res Online. 10(4):13–25.

- Jeffrey D. 2016. A meta-ethnography of interview-based qualitative research studies on medical students’ views and experiences of empathy. Med Teach. 38(12):1214–1220.

- Káplár-Kodácsy K, Dorner H. 2020. The use of audio diaries to support reflective mentoring practice in Hungarian teacher training. Int J Mentor Coach Educ. 9(3):257–277.

- Kenten C. 2010. Narrating oneself: reflections on the use of solicited diaries with diary interviews. Forum Qual Sozialforschung/Forum: Qual Soc Res. 11(2):314.

- Kolb DA. 2014. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall. ISBN: 0132952610

- La Caze S. 2017. Changing classroom practice through blogs and vlogs. Literacy Learn. 25(1):16.

- Lester D. 2017. Changes in the content of diary entries by a suicide as the date of death draws near. Suicidol Online. 8:114–117.

- McCoy LK. 2017. Longitudinal qualitative research and interpretative phenomenological analysis: philosophical connections and practical considerations. Qual Res Psychol. 14(4):442–458.

- McCreaddie M, Payne S. 2010. Evolving grounded theory methodology: towards a discursive approach. Int J Nurs Stud. 47(6):781–793.

- Metatla O, Bryan-Kinns N, Stockman T, Martin F. 2015. Designing with and for people living with visual impairments: audio-tactile mock-ups, audio diaries and participatory prototyping. CoDesign. 11(1):35–48.

- Milligan C, Bartlett R. 2019. Solicited diary methods. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Singapore: Springer; p. 1447–1464.

- Monrouxe LV. 2009. Solicited audio diaries in longitudinal narrative research: a view from inside. Qual Res. 9(1):81–103.

- Muir F, Law S. 2013. Getting Started… teaching reflective learning. Scotland (UK): University of Dundee.

- Munby H. 1989. Reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Curr Issues Educ. 9(1):31–42.

- Mychasiuk R, Benzies K. 2012. Facebook: an effective tool for participant retention in longitudinal research. Care Health Dev. 38(5):753–756.

- Neve H, Lloyd H, Collett T. 2017. Understanding students’ experiences of professionalism learning: a ‘threshold’approach. Teach High Educ. 22(1):92–108.

- Pilbeam C, Davidson R, Doherty N, Denyer D. 2016. What learning happens? Using audio diaries to capture learning in response to safety-related events within retail and logistics organizations. Saf Sci. 81:59–67.

- Rabionet SE. 2009. How I learned to design and conduct semi-structured interviews: an ongoing and continuous journey. Qual Rep. 16(2):563–566.

- Ramana KV, Kandi S, Boinpally PR. 2013. Ethics in medical education, practice, and research: an insight. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 6(6):599.

- Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. 2010. Theory in medical education research: how do we get there? Med Educ. 44(4):334–339.

- Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. 2013. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Med Teach. 35(8):e1365–e1379.

- Ringsted C, Hodges B, Scherpbier A. 2011. ‘The research compass’: an introduction to research in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 56. Med Teach. 33(9):695–709.

- Sandars J. 2009. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 44. Med Teach. 31(8):685–695.

- Sandars J, Murray C, Pellow A. 2008. Twelve tips for using digital storytelling to promote reflective learning by medical students. Med Teach. 30(8):774–777.

- Sheard L, Marsh C. 2019. How to analyse longitudinal data from multiple sources in qualitative health research: the pen portrait analytic technique. BMC Med Res Methodol. 19(1):1–10.

- Smithson J. 2000. Using and analysing focus groups: limitations and possibilities. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 3(2):103–119.

- Snaith B, Milner RC, Harris MA. 2016. Beyond image interpretation: capturing the impact of radiographer advanced practice through activity diaries. Radiography. 22(4):e233–e238.

- Stalmeijer RE, McNaughton N, Van Mook WN. 2014. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med Teach. 36(11):923–939.

- Stevenson N. 2016. Reflections upon the experience of longitudinal research into cultural event production in a developing destination. Int J Tourism Res. 18(5):486–493.

- Taylor SA. 2009. Engaging and retaining vulnerable youth in a short-term longitudinal qualitative study. Qual Soc Work. 8(3):391–408.

- Teague S, Youssef GJ, Macdonald JA, Sciberras E, Shatte A, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Greenwood C, McIntosh J, Olsson CA, Hutchinson D. 2018. Retention strategies in longitudinal cohort studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 18(1):151.

- Thomas DR. 2017. Feedback from research participants: are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qual Res Psychol. 14(1):23–41.

- Thompson T, Lamont‐Robinson C, Williams V. 2016. At sea with disability! Transformative learning in medical undergraduates voyaging with disabled sailors. Med Educ. 50(8):866–879.

- Välimäki T, Vehviläinen‐Julkunen K, Pietilä AM. 2007. Diaries as research data in a study on family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease: methodological issues. J Adv Nurs. 59(1):68–76.

- Van der Zwet J, Dornan T, Teunissen PW, de Jonge LPJWM, Scherpbier AJJA. 2014. Making sense of how physician preceptors interact with medical students: discourses of dialogue, good medical practice, and relationship trajectories. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 19(1):85–98.

- Verma A. 2020. Intersectionality, positioning and narrative: exploring the utility of audio diaries in healthcare students’ workplace learning. Int Soc Sci J. 70(237–238):205–219.

- Wald HS, Borkan JM, Taylor JS, Anthony D, Reis SP. 2012. Fostering and evaluating reflective capacity in medical education: developing the REFLECT rubric for assessing reflective writing. Acad Med. 87(1):41–50.

- Ward L, E Lamb S, Williamson E, Rebecca Robinson M, Griffiths F. 2019. O21 ‘Drowning in data!’ – designing a novel approach to longitudinal qualitative analysis. BMJ Open. 9:A8.2–A8.

- Warmington SG. 2019. Storytelling encounters as medical education: crafting relational identity. Milton Park: Routledge.

- Westberg J. 2001. Helping learners become reflective practitioners. Educ Health. 14(2):313–321.

- Williamson I, Leeming D, Lyttle S, Johnson S. 2015. Evaluating the audio-diary method in qualitative research. Qual Res J. 15(1):20–34.

- Worth N. 2009. Making use of audio diaries in research with young people: examining narrative, participation and audience. Sociol Res Online. 14(4):77–87.