Abstract

Purpose

Recruitment and retention of medical practitioners to rural practice is an ongoing global issue. Rural longitudinal integrated clerkships (LIC) are an innovative solution to this problem, which are known to increase rural workforce. Crucially this association increases with time on rural placement. This study examines factors that promote retention in a Rural LIC.

Methods

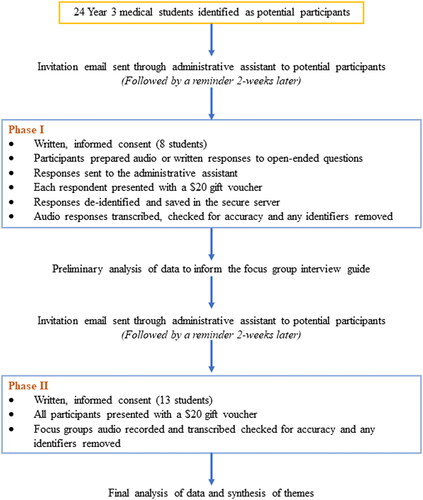

A two-phased, sequential design qualitative study in a cohort of students enrolled in a rural LIC at Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. Phase I consisted of an open-ended questionnaire and phase II follow-up focus groups from the same cohort. Data was transcribed and analysed using an iterative, six-step thematic analysis process to identify salient themes.

Results

Twenty-four students were invited to participate, of which eight respond in phase I and thirteen participated in phase II. Participants described retention being driven by connectivity within three broad themes: current practice, future practice (immediate internship and career intention), and social networks. Participant proposals to increase connectivity were also suggested including peer-led solutions and short rotations in metropolitan hospitals.

Conclusion

Connectivity is key to retention on rural longitudinal integrated clerkships. Programs which enhance connectivity with current practice, future practice, and social networks will increase retention on rural medical programs.

Introduction

Recruitment and retention of medical practitioners to rural practice is an ongoing global problem; the shortfall leading to inequitable access to healthcare and poorer health outcomes (Fisher and Fraser Citation2010). Rural longitudinal integrated clerkships (LIC) are an innovative solution to medical workforce maldistribution (Walters et al. Citation2012). Providing an alternative to traditional block-based programs, rural LICs place students in generalist rural practice for extended periods of time and allow students to learn clinical disciplines in an integrated manner whilst encouraging them to pursue a rural career (Hauer et al. Citation2012; Walters et al. Citation2012; Thistlethwaite et al. Citation2013; Worley et al. Citation2016).

The LIC model has been well described and validated as a viable means of medical education, supporting the student learning experience in a variety of ways (Walters et al. Citation2012; Worley et al. Citation2016). Students who partake in the LIC model develop stronger higher-order clinical and cognitive skills, better patient-centred communication, increased understanding of culturally safe practice and have higher levels of student satisfaction (Walters et al. Citation2012; Teherani et al. Citation2013; Purea et al. Citation2022). Studies suggest a positive association between length of rural clerkship and the increased likelihood of rural practice (McDonnel Smedts and Lowe Citation2008; Playford et al. Citation2015; O'Sullivan et al. Citation2018; O'Sullivan and McGrail Citation2020). Longer rural immersion increases a sense of belonging and connection to the rural community, which can enhance student experience and in turn increase rural career preference (Daly et al. Citation2013; Roberts et al. Citation2017). This appears to have a greater impact than rural origin on subsequent career location choice (Clark et al. Citation2013).

Practice points

Students remain on rural programs when there is connectivity with current practice, future practice and social networks.

Well designed and administered rural longitudinal integrated clerkships can promote retention in rural educational placement.

Rural LICs should continue to afford students immersive hands-on practice where they are known to the team and their learning is visible.

Students value peer-peer connection highly and focusing on peer-led promotion will improve retention.

Innovative short placements in metropolitan hospitals can minimise students fears of missing out on learning experiences perceived to prepare students for intern placement.

Although factors that promote entry into rural LICs are described, factors driving students to remain in rural LICs are not well established (Jones et al. Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2007; Denz-Penhey and Murdoch Citation2009; Herget et al. Citation2021). It is important to understand these factors to maximize engagement with extended rural LIC programs and in turn increase rural workforce. This study examines the preferencing decisions of a cohort of rural medical students enrolled in the Griffith University (GU) ‘Longlook’ rural LIC program and aims to explore factors which influenced their decisions to continue in this program.

Materials and methods

Study setting and context

The GU’s medical program is a four-year postgraduate medical degree delivered though campuses and health service institutions in Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast and rural Queensland, along with one site in Northern Rivers, New South Wales. GU students have the option to engage in a rural LIC program (‘Longlook’), unique as it is delivered in partnership with a not-for-profit organisation, Rural Medical Education Australia. Established in 2010, Longlook immerses students in small rural communities across southeast and southwest Queensland for the entire clinical year in Year 3 and/or 4 (Kitchener et al. Citation2015). Students are allocated to the program through open preferencing at the end of Year 2 or 3. Internal data indicates that approximately 15% of Longlook students who start the program in Year 3 remain for two years.

Based on data from the annual Federation of Rural Australian Medical Educators survey (FRAME Citation2023), Longlook students are predominantly female (68%) with a mean age of 25.5 years (range 21–57 years). Approximately one in four students considered themselves from a rural background and over two thirds indicated a non-general practice specialty career preference on entry to the program. The cohort was overly positive of the Longlook program, 23% indicated preference to pursue a rural generalist career pathway and a further 13% intended to pursue general practice.

This study was developed utilising a pragmatic philosophical approach whereby the researchers identified and utilised the best available methods to answer the research question. The research focused on real-world experiences of students to develop an understanding of the practical solutions for improving retention of students within rural programs (Giacomini Citation2010). Data was analysed using the iterative, 6-step thematic analysis process described by Braun and Clarke (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee granted approval for the study (GU 2021/348).

Reflexivity

The principal investigator, BC, is an experienced rural generalist and Year 3 Medical Lead within the Longlook Program. KB and HW are academic GPs. JP and SW are clinical researchers. LB was a Year 4 Medical student at the time of the study. The research team members are all rurally located and actively engaged in delivering a successful Rural LIC program.

Participants and procedures

We performed a two-phased, sequential design qualitative study (). We invited all Year 3 students from a single Longlook cohort to participate in both phases. Students had completed two thirds of the Year 3 curriculum. Phase I included responding to a set of open-ended questions through either audio recording or written responses. Phase II consisted of follow-up focus groups from the same student cohort. Voluntary informed consent was obtained during both phases. In Phase II this included permission for audio-recording of the focus groups. Students who chose to participate were anonymous to the research team, other than one focus group led by LB.

Data collection

Email invitations with study information for each phase were sent to all eligible participants. Follow-up emails were sent to all intended participants two weeks after initial emails. Data collection for Phase I was kept open for 4-weeks. The Year 3 Medical Lead (BC) also informed the students of the proposed study during educational training days and encouraged their participation.

In Phase I, consenting students were emailed a set of study questions (Supplementary Appendix) and asked to provide written or audio responses. Questions were developed by the study team based on their experiences within the Longlook program. Once responses were received, they were deidentified and stored in a secure server by the program administrative assistant.

For Phase II, consenting students were allocated to one of two focus groups. To encourage students to give informed, honest, and open answers, focus groups were scheduled one month following phase I and after Year 4 placements were finalized. Focus groups were facilitated by two investigators who had previous learning experiences in rural LIC programs but had no responsibility for student assessments.

Audio responses to Phase I questions and audio recordings from Phase II focus groups were transcribed using Sonix® (Sonix.ai, San Francisco, USA). Transcripts were re-checked manually for accuracy by LB who was not involved in assessing medical students. All identifiers were removed before transcribed data were shared with the other study investigators. Respondents received a $20 gift voucher for participation in each phase.

Data analysis

BC read three transcripts and developed the initial codebook. Then LB applied these codes to a fourth transcript and further refined the codes. All 8 transcripts from Phase I were then coded using the revised final codebook by the same two investigators (BC and LB). Preliminary analysis of Phase I data generated cues for developing Phase II focus group questions.

The Phase II focus group sessions helped to ensure that the research team’s interpretation of the results from the preliminary analysis of the open-ended questions from Phase I was an accurate representation of the student experiences. Similar to Phase I, BC read one transcript and developed the initial codebook. Then SW applied these codes to the second transcript and further refined the codes. Both transcripts from Phase II were then coded using the revised final codebook by BC and SW. For both phases, any coding disputes were reconciled through discussion with a third investigator (JP).

Once coding was completed, data were synthesised to identify themes. Considering varied student experiences encountered, we attempted to describe the larger themes whilst preserving the individual variations. NVivo software (QSR International, VIC, Australia) was used for coding and analysis of the transcripts. To improve the validity and reliability of data and aid in reviewing the integrity of the information provided by the respondents (Anney Citation2014), we used data triangulation through use of different data collection methods (individual responses and focus groups) and time triangulation by collecting and comparing similar data at two different time points.

Results

Twenty-four students were invited to participate in the study. Eight responded in Phase I (written = 6, audio = 2) and thirteen in Phase II (two focus groups of six and seven students each). Seven participants from Phase I participated in Phase II.

Participants described an intwined connectivity that was woven across three broad themes that emerged from the data (). When the program created connectivity with current practice, future practice and/or social networks, ongoing rural placement was promoted and positive learning effects enhanced. Students also suggested program recommendations which they felt would enhance connectivity across these themes.

Current practice

Current practice is the immediate work of a student (activities that had to be performed to progress in their medical studies). Students reported being driven to preference ongoing rural placement due to the connectivity of practice in a rural longitudinal program. They valued immersive practice in which they were connected to patients with practical hands-on learning.

I chose rural… because I really wanted a hands-on experience and I was quite scared of being lost,… told to stand in a corner and not being able to do anything… I learn from doing. Participant (P) 1-4

There was a desire to be immersed as part of a team in which they were known and their learning in practice was visible.

Knowing your name and you’re there for the entire year doing the same sorts of things. So, you’re not going from one block to the next where you have to… re-meet everyone, you sort of can become part of the team. I really like that. P2-3

When you go to a metropolitan area, you get, like, forgotten very easily… But in a rural place, they actually make you feel like you’re part of their team… and because of that, there is the opportunity to learn the skill sets quite easily. P1-5

This connectivity of practice was enhanced by smaller cohort of students and less competition from other learners which afforded more opportunities to develop a connected practice.

Speaking about surgeries. It’s quite interesting because in the metropolitan area… you’re just going to be… observing on top of like 10 other people, really. But… in rural, you actually get to assist as a first, as a second assistant, you get to actually do things. P1-5

This contrasted with metropolitan placement where students describe competing for opportunities and thus being peripheral to practice with a lack of continuity of care with patients.

I can go to [a metropolitan hospital] and I can stand in a corner and see and see lots of things but do nothing. Or I can go to [a rural hospital] and be hands on for another whole year and get that experience. And that was an easy choice. P1-3

Future practice

Future practice encompasses a student’s perceived work after graduation and students were intensely concerned with their immediate future practice as an intern. Due to the practical hands-on learning experience, ongoing rural placement was seen as providing an enhanced practical preparation for internship.

I would argue that the Longlook program… prepares you very well for internship.… There’s not really much that that I see our interns doing that I’m not doing already. …while there is that fear that if you get a metro hospital for internship, you might not know what you’re doing because you’ve never been there before. I think that our basics that we’ve learnt this year really prepare us for that, for sure. P1-3

However, the greatest barrier to returning to rural placement was an intense fear of missing out. Rural practice was seen as displaced from the work of an intern, which mostly occurs in larger hospitals. Although students developed broad clinical skills, they were unsure if they were transferable. Students perceived a need to understand the differing system of a metropolitan hospital in order to be able to act as an effective intern.

I'm going to spend at least,… two or three years in a larger centre. You do want to know how that works. You want to know how… physicians want their referrals. You want to know how a surgical unit operates beyond what I see at [a rural hospital], which is obviously very different.… I have a concern that I'll start internship, and… hypothetically, they might use a different system to [Emergency Department Information System], they might do electronic,… charting and whatnot. And I won’t have seen that at all. P1-2

Despite the immediate future practice as an intern being generalist in nature, students perceived that minimal teaching from non-general practice specialists would be a disadvantage.

When you’ve been rural third year, if you’re coming back fourth year… you’ve never experienced like a big [Emergency Department], like you’ve seen a lot of [Emergency Department] presentations, right? But like you’re not working under [Fellows of the Australian College of Emergency Medicine], like there they have [specialist] training, that’s their job. P2-2

I think before I started this year, I was worried about that,…physicians know their trade best. So… if I'm just learning from a generalist, am I going to be learning best practice? P1-2

They also described rural hospitals were patching and stabilising patients for retrieval and perceived a need to see and learn the higher-level care that occurs in the tertiary centre.

We’re just packing them and sending them. And sometimes I think to myself, I would like to be on the other end of that and receive a patient and then figure out exactly what’s wrong with them, exactly what we need to do. P1-3

Finally, career intention had a strong influence on preferencing decisions. Students with a rural career intention reported a desire to continue the rural program and students with a strong speciality preference returned to a larger centre.

I really do see myself being a [Rural Generalist] and [a rural hospital] seems to be the epitome of where a [Rural Generalist] will work, and it’s the best way that, the best place where a [Rural Generalist] can work and learn, so it was, it was good. P2-3

Most of the specialties… [are] in [metropolitan] centers… that’s the biggest reason why… [students] want to go there because they are under the illusion… if you get there early and build rapport… someday when we come back we’ll be able to sweet talk our way [onto] the pathway. P1-5

Social networks

Social networks refer to a student’s integration within the various groups associated with their placement. Socially, students wanted connectivity across their rural community, clinical community, and peers. A placement with a close social network positively influenced students to remain on the rural program.

I reckon on the plus side we’re very integrated into the community. We get along very well with, like a lot of the hospital staff, it’s a lot of new friends. We’re very rarely strapped for something to do. P1-2

The most significant social factor was connectivity with the peer network which had a profound impact on promoting further rural placement.

I think like having attended an informal [information] evening where you can kind of just wander around and chat to people and get different experiences from… [a rural medical student] who has done rural two years. Someone who’s done rural one year and metro another year. P1-2

Students also valued connectivity with personal hobbies and sporting interests.

Cricket. Absolutely.… that’s absolutely part of it.… It’s one of the biggest reasons [for preferencing rural year 4]. P1-5

These positive influences were contrasted with the effects of social displacement with many students discouraged from continuing rural placement as they felt displaced from pre-existing social networks.

I was going to get back to the coast, yeah. Mainly because of the lack of like the extracurricular things that I like doing, none of its out rural. Yeah. So, it was a negative also for me. P2-2

So, like being close to family and friends and things like that.… So, I felt a little bit isolated being in [a rural hospital] this year with that. P2-3

Participant recommendations

Students suggested a number of program factors to maximise connectivity on the rural program including: student contact lists, organised student functions, Year 4 led teaching and promoting informal networks through co-location with Year 4 students.

Make a list of students that are happy to [answer] questions, potentially also because not everyone has fourth years at their side and not everyone has fourth years that they have a connection with. Have something at [rural cohort teaching] where it’s just students, like no silly questions, there’s no educators there… do questions that you can ask, something that’s facilitated P2-2

What you can do is… a lecture… say, [vaginal] bleeding…. One of the fourth years could do some parts of it… [and] in the end you say, ‘… I'm hanging around… if you have any questions about year four, come and talk to me.’ P1-5

Multimodal approaches to peer-led support were suggested such as orientation books or student produced site videos.

Make a video… you’re out here rural and like [in a rural hospital], you see …, [a general practitioner obstetrician], [doing a category 1 caesarean section]. An hour later, they’re down in [the Emergency Department] seeing some… sick [patient] with a heart attack. Yeah, like they’ve just done a [caesarean section], they’re [placing] an [arterial line]. These people… they’re so good, but it’s crazy. P2-2

Students, however, were specific that the media or events need to be peer-led as they perceived the vested interests of academic staff.

Staff. Yeah, I kind of listened to them and I was like, oh, like, I'm taking it with a grain of salt because I know you want to get students coming to Longlook. P1-2

Although many students acknowledged that ‘the grass is always greener on the other side’, the only way to know this is to be afforded access to metropolitan experiences. They noted that short duration placements in larger hospitals would make metropolitan practice less opaque and combat the fear of missing out. Along with this they noted that some non-generalist specialist teaching would both alleviate the disconnection associated with the fear of missing out but also foster connectivity with non-generalist speciality focused students.

Connectivity takes time and students indicated they were thinking about Year 4 rural practice much earlier than the preferencing window. Interestingly, students listed events from preclinical years such as Year 1 clinical placements and early clinical skills trips as influencing decisions for Year 4. Students also discussed a preference for more preclinical information sessions. Even in Year 3 students wanted information very early in the year.

But the reason I was looking at [rural placement] for fourth year… [was] The Rural Skills Trip. I went to the one in [a rural hospital] and [another rural hospital], which was sort of a nice sort of demonstration of… all the sorts of experiences that the students had. P2-3

For me, [the information session] was also too late. Like do it earlier. So you can kind of mull your thoughts over and then come back to it with questions. P2-2

Finally, flexibility in the program where students were able to work closely with supervising clinicians to arrange the roster to facilitate social engagements, was also thought to enhance connectivity with family networks.

Flexibility has actually meant that I get better time with [family] because I'm so busy at the hospital anyway that I wouldn’t have had time to go see them. And then I do get that like day or two-day block and see them like maybe on the weekend, once a fortnight.… So, I still get to maintain that relationship with my family. P2-2

Discussion

Here, we present that it is connectivity, woven across three broad themes, that promotes student retention on rural LIC programs. Results are similar to the broader rural training pathway where factors influencing the progression of students into independent rural clinical practice are well established (Henry et al. Citation2009; Fisher and Fraser Citation2010). Connection to place through rural origin and early positive rural educational experiences are strong drivers for rural health career preference (Fisher and Fraser Citation2010). The influence of ‘connectedness’ particularly to community is also described as a key driver for rural workforce retention (Campbell et al. Citation2012). Drivers for entry into a rural program have also been previously reported, however this study uniquely presents factors influencing continued placement on a rural LIC (Jones et al. Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2007; Denz-Penhey and Murdoch Citation2009; Herget et al. Citation2021).

Rural LICs by design, promote connectivity with patients, supervisors, and community (Hirsh et al. Citation2007; Norris et al. Citation2009). This connectivity is fundamental to learning within the LIC model and an important pathway to preparedness for future practice (Roberts et al. Citation2017). Students value the immersive and hands on learning environment of LIC programs, providing more connection with patients compared with traditional block programs (Irby Citation1995). This experience leads to increased clinical confidence and integration into the team in a more independent ‘doctor-like’ role, as described by students (Worley Citation2002; Hauer et al. Citation2012; Walters et al. Citation2012). Connectivity is also central to retention on rural LICs. If students are placed in a well-designed and administered rural LIC program which promotes connectivity, ongoing placement will be promoted.

Social connectivity is vitally important for promotion of ongoing placement. An important aspect highlighted by participants is connection with the peer network. Herget et al. (Citation2021), report that among German students in clinical years, peer-led promotion was ranked as most likely to influence rural placement. Similar to what is reported here, peer-led promotion included reports of student experiences, informal student events, advertisement through student publications and social media. Peer-peer impact has similarly been demonstrated as important in other areas such as study abroad programs (Herget et al. Citation2021).

Students were intensely focused on connectivity with their immediate future practice as an intern. This concern with both practice as an intern and as a speciality trainee is reported widely. Participants consistently report concerns with access to subspecialty teaching and access to complex patients as key negative influences for rural practice (Jones et al. Citation2000; Jones et al. Citation2005; Jones et al. Citation2007; Denz-Penhey and Murdoch Citation2009; Konkin and Suddards Citation2015). Denz-Penhey and Murdoch (Citation2009) also report the perception that ‘all the interesting cases get shipped off to the city.’ This was despite demonstrating adequate breadth and complexity of the rural patient cohort. Konkin and Suddards (Citation2015) examined perceptions on which students should preference a rural LIC and described career goals as a key theme. Similar to our cohort, they describe a balance between connection with current and future practice. Participants acknowledged that a rural LIC provided an appropriate education that prepared them for future practice. However, they perceived that rural placement could render them less competitive for subspeciality training. Our participants suggest an approach to enhancing connectivity with future practice through short placements in metropolitan hospitals which should be considered in rural LIC models.

Of most interest is what students did not report as influencing ongoing placement preference. No student reported financial incentives as influencing preferencing decisions. This is in contrast to other studies in which financial incentives are ranked highly (Jones et al. Citation2007; Herget et al. Citation2021). However, Denz-Penhey and Murdoch (Citation2009) report that students value connectivity with current practice highly and will sacrifice other factors in order to obtain it. The GU Longlook Program is well established and highly regarded by students, and this may be masking the influence of financial incentives in this cohort. Significant financial incentives are already provided as a part of the program through rental subsidy and travel assistance. Similar to findings by Denz-Penhey and Murdoch (Citation2009), despite indicating that further incentives may not influence preferencing, this study may not adequately assess what influence the absence of existing benefits would have, given students indicated they were adequately financially supported.

This study focuses on a single cohort of students from a rural LIC program, which has a unique context. The students interviewed had selected a year-long rural longitudinal clerkship in rural Queensland. As such, the effective transfer of study findings to other contextually similar rural programs may require further study in additional cohorts, programs and contexts.

Rural LICs are an effective educational intervention to reduce workforce maldistribution. This study presents that connectivity is key to retention on rural LICs. Students need connectivity with current practice, future practice, and social networks. Programs which enhance connectivity with these factors will increase retention on rural medical programs. Although rural LIC design, by nature, will promote connectivity, programs should consider enhancing immersive hands-on practice, increasing peer support and promotion, and creating short-duration metropolitan placements. Future research should confirm these findings in a variety of programs and settings.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Brendan Carrigan

Brendan Carrigan, AFRACMA, GCAHP, FACRRM, DRANZCOG Adv., MBBS, BSc(Hons), is the Year 3 Clinical Lead for the Griffith University Longlook program at Rural Medical Education Australia, Toowoomba, Australia and a Senior Lecturer at the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Australia.

Lucy Bass

Lucy Bass, MD, BHSc, was a Year 4 medical student in the Griffith University Longlook Program at the time of the study. Lucy is now a Resident Medical Officer with Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Caboolture Hospital, Caboolture, Australia.

Janani Pinidiyapathirage

Janani Pinidiyapathirage, MBBS, MSc, MD, PhD, is Associate Professor at Rural Medical Education Australia, Toowoomba, Australia and the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Australia.

Sherrilyn Walters

Sherrilyn Walters, MScR, BAppSc, is Research Assistant at Rural Medical Education Australia, Toowoomba, Australia and the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Australia.

Hannah Woodall

Hannah Woodall, BMedSci, MBBS, FRACGP, is a Research Fellow at Rural Medical Education Australia, Toowoomba, Australia and Senior Lecturer in the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Australia.

Kay Brumpton

Kay Brumpton, MBBS, FRACGP, FARGP, FACRRM, DRANZCOG, MClinEd, GAICD, is Professor and Subdean Rural at the School of Medicine and Dentistry, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Southport, Australia, and Director, Education and Training at Rural Medical Education Australia, Toowoomba, Australia.

References

- Anney VN. 2014. Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: looking at trustworthiness criteria. J Emerg Trends Educ Res Policy Stud. 5:272–281.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Campbell N, McAllister L, Eley D. 2012. The influence of motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and remote allied health professionals: a literature review. Rural Remote Health. 12:1900.

- Clark TR, Freedman SB, Croft AJ, Dalton HE, Luscombe GM, Brown AM, Tiller DJ, Frommer MS. 2013. Medical graduates becoming rural doctors: rural background versus extended rural placement. Med J Aust. 199(11):779–782. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10036.

- Daly M, Roberts C, Kumar K, Perkins D. 2013. Longitudinal integrated rural placements: a social learning systems perspective. Med Educ. 47(4):352–361. doi: 10.1111/medu.12097.

- Denz-Penhey H, Murdoch JC. 2009. Reported reasons of medical students for choosing a clinical longitudinal integrated clerkship in an Australian rural clinical school. Rural Remote Health. 9(1):1093.

- Fisher KR, Fraser JD. 2010. Rural health career pathways: research themes in recruitment and retention. Aust Health Rev. 34(3):292–296. doi: 10.1071/AH09751.

- FRAME. 2023. Federation of rural Australian medical educators; [accessed 2023 Feb 20]. https://ausframe.org/.

- Giacomini M. 2010. Theory matters in qualitative health research. In: The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods in health research. London: SAGE Publications; p. 125–156.

- Hauer KE, Hirsh D, Ma I, Hansen L, Ogur B, Poncelet AN, Alexander EK, O'Brien BC. 2012. The role of role: learning in longitudinal integrated and traditional block clerkships. Med Educ. 46(7):698–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04285.x.

- Henry JA, Edwards BJ, Crotty B. 2009. Why do medical graduates choose rural careers? Rural Remote Health. 9(1):1083.

- Herget S, Nafziger M, Sauer S, Bleckwenn M, Frese T, Deutsch T. 2021. How to increase the attractiveness of undergraduate rural clerkships? A cross-sectional study among medical students at two German medical schools. BMJ Open. 11(6):e046357. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046357.

- Hirsh DA, Ogur B, Thibault GE, Cox M. 2007. Continuity as an organizing principle for clinical education reform. N Engl J Med. 356(8):858–866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb061660.

- Irby DM. 1995. Teaching and learning in ambulatory care settings: a thematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 70(10):898–931. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199510000-00014.

- Jones AR, Oster RA, Pederson LL, Davis MK, Blumenthal DS. 2000. Influence of a rural primary care clerkship on medical students’ intentions to practice in a rural community. J Rural Health. 16(2):155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00449.x.

- Jones GI, DeWitt DE, Cross M. 2007. Medical students’ perceptions of barriers to training at a rural clinical school. Rural Remote Health. 7(2):685.

- Jones GI, DeWitt DE, Elliott SL. 2005. Medical students’ reported barriers to training at a rural clinical school. Aust J Rural Health. 13(5):271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2005.00716.x.

- Kitchener S, Day R, Faux D, Hughes M, Koppen B, Manahan D, Lennox D, Harrison C, Broadley SA. 2015. Longlook: initial outcomes of a longitudinal integrated rural clinical placement program. Aust J Rural Health. 23(3):169–175. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12164.

- Konkin DJ, Suddards CA. 2015. Who should choose a rural LIC: a qualitative study of perceptions of students who have completed a rural longitudinal integrated clerkship. Med Teach. 37(11):1026–1031. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1031736.

- McDonnel Smedts A, Lowe MP. 2008. Efficiency of clinical training at the northern territory clinical school: placement length and rate of return for internship. Med J Aust. 189(3):166–168. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01953.x.

- Norris TE, Schaad DC, DeWitt D, Ogur B, Hunt DD, Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated C. 2009. Longitudinal integrated clerkships for medical students: an innovation adopted by medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. Acad Med. 84(7):902–907. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a85776.

- O'Sullivan BG, McGrail MR, Russell D, Walker J, Chambers H, Major L, Langham R. 2018. Duration and setting of rural immersion during the medical degree relates to rural work outcomes. Med Educ. 52(8):803–815. doi: 10.1111/medu.13578.

- O'Sullivan BG, McGrail MR. 2020. Effective dimensions of rural undergraduate training and the value of training policies for encouraging rural work. Med Educ. 54(4):364–374. doi: 10.1111/medu.14069.

- Playford DE, Nicholson A, Riley GJ, Puddey IB. 2015. Longitudinal rural clerkships: increased likelihood of more remote rural medical practice following graduation. BMC Med Educ. 15:55. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0332-3.

- Purea P, Brumpton K, Kumar K, Pinidiyapathirage J. 2022. Exploring the learning environment afforded by an aboriginal community controlled health service in a rural longitudinal integrated clerkship. Educ Prim Care. 33(4):214–220. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2022.2054371.

- Roberts C, Daly M, Held F, Lyle D. 2017. Social learning in a longitudinal integrated clinical placement. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 22(4):1011–1029. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9740-3.

- Teherani A, Irby DM, Loeser H. 2013. Outcomes of different clerkship models: longitudinal integrated, hybrid, and block. Acad Med. 88(1):35–43. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318276ca9b.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Bartle E, Chong AA, Dick ML, King D, Mahoney S, Papinczak T, Tucker G. 2013. A review of longitudinal community and hospital placements in medical education: BEME Guide No. 26. Med Teach. 35(8):e1340-1364–e1364. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.806981.

- Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, Ward H, Campbell N, Ash J, Schuwirth LW. 2012. Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society. Med Educ. 46(11):1028–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04331.x.

- Worley P, Banh KV, Couper I, Strasser R, Graves L, Cummings B-A, Woodman R, Stagg P, Hirsh D, Barnard A, et al. 2016. A typology of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Educ. 50(9):922–932. doi: 10.1111/medu.13084.

- Worley P. 2002. Relationships: a new way to analyse community-based medical education? (Part one). Educ Health: Change Train Pract. 15(2):117–128.