Abstract

What was the educational challenge?

Medical student abuse within work-integrated learning (WIL) is well-reported, with negative consequences for wellbeing, motivation, and learning. Conversely, workplace dignity, described as respecting the worth of others and self, has positive impacts on wellbeing, learning, and relationships for WIL students and supervisors. Stakeholders often struggle to articulate what workplace dignity means, and can downplay or do nothing in the face of WIL indignities.

What was the solution and how was this implemented?

We created an innovative research-informed online learning resource about WIL dignity to improve stakeholders’ understandings and help them get the best from WIL placements ensuring these are dignified, safe, and educationally productive. The resource included three topics: (a) workplace dignity and why it matters; (b) upholding dignity; and (c) strengthening dignity.

What lessons were learned?

We conducted a pilot qualitative evaluation involving 13 semi-structured interviews with students and supervisors to elicit their views and experiences of the resource. Our key findings across three overarching categories were: (1) perceived benefits (motivations to complete the resource; content of the resource; online pedagogies); (2) potential applications of learning (reinforcing existing knowledge; developing new knowledge; promoting reflection; changing workplace practices); and (3) suggested improvements (barriers to resource use; resource content; online pedagogies; timing of resource implementation; embedding the resource in broader learning).

What are the next steps?

Although we identified numerous perceived benefits, and applications of learning, the findings suggested opportunities for further development, especially improving the resource’s social interactivity. We recommend that further resource implementation includes student-educator and student-peer interactivity to maximise learning, and longitudinal evaluation of the resource.

What was the educational challenge?

While the concept of dignity is infrequently employed within medical and health professions education (Davis et al. Citation2020), it is relevant to ongoing problems in work-integrated learning (WIL) placements, where student abuse is widespread (Monrouxe and Rees Citation2017). Over decades, studies have reported healthcare students and professionals receiving verbal and physical abuse, sexual, racial and ability-based discrimination, and other more subtle forms of abuse, such as being excluded or ignored, given destructive feedback, or unpleasant tasks during WIL (Monrouxe and Rees Citation2017). These WIL abuses can lead to negative wellbeing (including anxiety, depression, moral distress, and lack of confidence), reduced motivation, attrition from the profession, suboptimal learning, and poor professional identity development (Davis et al. Citation2020; King et al. Citation2021). Conversely, workplace dignity, described as people feeling, thinking, and behaving in ways that respect the value or worth of others and self (Davis et al. Citation2020; King et al. Citation2021), has positive consequences for WIL students and supervisors, including wellbeing, increased learning, and improved student-supervisor relationships (Davis et al. Citation2020).

While widespread recognition of WIL abuse exists amongst stakeholders, our research found that WIL students and supervisors often struggle to articulate what workplace dignity means (King et al. Citation2021). Although WIL students and supervisors sometimes act in the face of dignity violations (e.g. reporting perpetrators, debriefing with supportive colleagues), they often downplay such violations or do nothing, potentially perpetuating workplace indignities (Monrouxe and Rees Citation2017).

What was the solution and how was this implemented?

Drawing on our rich research findings (e.g. Davis et al. Citation2020; King et al. Citation2021), which suggested that WIL dignity experiences were more similar than different across disciplines, and that students showed little appreciation of supervisors’ dignity experiences during WIL (Rees et al. Citation2020), we developed an innovative research-informed, open-access asynchronous online learning resource about WIL dignity that would help prepare WIL students and supervisors for placements through improving their understanding. This resource, called: ‘Dignity during work-integrated learning: Your right and your responsibility’, was launched in October 2019 (https://ilearn.med.monash.edu.au/dignity/index.html#/menu/5d3521caf8d10b57dcddac35). This was designed to be suitable for students and supervisors (to facilitate their appreciation—and empathy—of one another’s dignity) across wide-ranging disciplines.

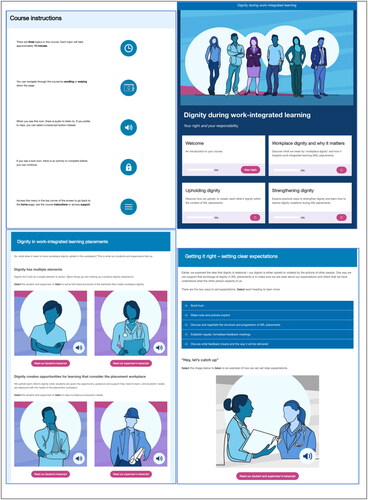

The resource was designed to take 30 min to complete covering three topics: (a) workplace dignity and why it matters (i.e. what workplace dignity means, and how it impacts WIL placements); (b) upholding dignity (i.e. how student and supervisor dignity can be upheld or violated during WIL placements); and (c) strengthening dignity (i.e. practical ways to strengthen dignity and learning how to resolve dignity violations within WIL placements). Working with an industry partner (The Learning Hook), we included multiple design elements into this resource to facilitate its successful uptake, aligning with latest evidence and theory about how online learning works (Wong et al. Citation2010). Features included: (a) clear course instructions to aid navigation; (b) structuring the resource into three bite-size topics with summaries to facilitate easy use and comprehension; (c) active/experiential learning (through use of clickable links, listening to and reflecting on real stories); and (d) interactivity to enhance learners’ engagement with the platform and content (through varied use of text, videos, images, audios, and opportunities for reflection). Our resource met equity, diversity, and inclusion standards by ensuring diverse genders and cultural and linguistic backgrounds were represented in images and talk (see for examples of design elements). Finally, we made this resource available as a PDF transcript for those with reading preferences. We recommended the resource be used in multiple ways (e.g. pre-placement preparation for students and training materials for supervisors).

Figure 1. Examples of design elements employed in the WIL dignity online resource to facilitate its successful uptake including course instructions, structuring topics into bite-sized chunks, incorporating experiential/active learning, interactivity, and equity, diversity, and inclusion principles wherever possible.

What lessons were learned?

We conducted a pilot qualitative evaluation following institutional ethics approval (reference no. 21772), which aimed to elicit WIL students’ and supervisors’ views and experiences of the resource. Ten students and nine supervisors participated in this evaluation across four groups (two student, two supervisors) and nine individual interviews. Students ranged in age from 21 to 49 years (median = 24, IQR = 22–29) and supervisors from 42 to 63 years (median = 52, IQR = 48–54). Six students and one supervisor were from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Nearly all participants were females (n = 18), with a majority from health-related disciplines—medicine, nursing, and counselling (n = 13). The interviews explored participants’ motivations to complete the resource, what they enjoyed about the resource or not, and why, and suggestions for modifying the resource. Interviews ranged from 21 to 61 min (total = 424 min). We analysed the transcribed interview data employing a team-based five-stage framework analysis.

We present here our key lessons learned across three over-arching categories, collating multiple themes and sub-themes identified through our framework analysis (see the supplementary materials for details of themes and illustrative quotes) that are relevant to a wider global audience. We found no major differences between students’ and supervisors’ perspectives.

Learning 1: The online resource has several benefits, including diverse motivations for completion, valuable content, and the advantages of online pedagogies.

Learning 2: The resource has numerous potential applications, such as reinforcing existing knowledge, developing new knowledge, promoting reflection, and changing workplace practices.

Learning 3: There are scopes to improve the resource and maximise learning outcomes, such as overcoming barriers to resource use (e.g., supervisor sensitivity, time constraints), improving resource content (e.g., immediate applicability and relevance of knowledge), enhancing online pedagogies (e.g., promoting social interactivity), optimising the timing of resource implementation, and integrating the resource into broader student and supervisor learning initiatives.

What are the next steps?

The most compelling recommendations made by our pilot evaluation participants related to building social interactivity into the resource, or embedding the resource within broader learning involving face-to-face interaction with teachers and/or peers. While the asynchronous and standalone nature of our resource enabled flexibility, convenience, and economies of scale (given the low educator input), it lacked meaningful interactivity, prohibiting learners from opportunities to receive feedback, or clarify their comprehension of the content (Wong et al. Citation2010). We therefore recommend that our resource is properly contextualised within broader social learning as part of student and supervisor orientations to WIL. For example, groups of students or supervisors could work through the resource together in a 2–3 h workshop (either online or in-person) to make sense of the content collectively. They could engage in active, reflective, and social learning activities based on their own WIL dignity experiences, using role-playing strategies for resolving WIL dignity violations (Monrouxe and Rees Citation2017). Such interactivity would enable them to ask questions, receive feedback on their understandings and experiences, and help them to apply new knowledge to their future WIL practices.

While our pilot evaluation sample was reasonably diverse (e.g. age and CALD background), it lacked diversity in terms of gender. The sample was relatively small (n = 19) and from one Australian University, potentially limiting the transferability to other contexts (e.g. outside of Australia), and to students and supervisors not well-represented in our sample (e.g. males). Therefore, we invite educators involved in WIL placements and placement organisations to access this free, open-access resource to critically review it and gauge whether it is suitable for their own context. To our knowledge, completion of the resource is mandatory for various Monash University student cohorts (e.g. medicine, nutrition & dietetics, nursing, midwifery), and supervisor cohorts (e.g. general practice, public health nutrition). Where relevant, we encourage educators to embed this resource in broader WIL placement orientations for students and supervisors involving social interactivity with educators and peers, and we encourage them to conduct further evaluations in their own context, especially longitudinal evaluations exploring applications of new knowledge to the workplace context. We hope this resource will help to improve student and supervisor dignity experiences during WIL, leading to positive benefits at the level of individual (e.g. wellbeing, improved learning), interactions (e.g. improved student-supervisor relationships), and environment (e.g. improved workplace retention).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank our collaborators involved in the foundational research for the resource (Allie Clemans, Jan Coles, Paul Crampton, Nicky Jacobs, Tui McKeown, Julia Morphet, and Kate Seear); and those involved in its development, including The Learning Hook. We also thank Tammie Choi for her co-supervision of Kadheeja Wahid and express our gratitude to evaluation participants for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

The resource is a free, open-access online resource: https://ilearn.med.monash.edu.au/dignity/index.html#/menu/5d3521caf8d10b57dcddac35. Authors CR, OK and CD were involved in the resource development, but received no financial compensation or incentives for others using this resource. The pilot evaluation of the resource was led by co-authors not involved in resource development.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mahbub Sarkar

Mahbub Sarkar, BEd (Hons), MEd, PhD, SFHEA, is a Senior Lecturer at Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education, and an Academic Development Specialist at Monash Education Academy, Monash University.

Corinne Davis

Corinne Davis, BNutrDiet (Hons), BArts (Hons), MUP, is an Accredited Practising Dietitian and PhD Candidate at the Department of Nutrition, Dietetics and Food, Monash University.

Olivia King

Olivia King, BPod (Hons), Grad Cert Diab Ed, PhD, is Manager of Research Capability Building with Western Alliance and an Adjunct Research Associate with the Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education.

Kadheeja Wahid

Kadheeja Wahid, BNut, MDiet, was a student researcher at Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education, Monash University.

Charlotte E. Rees

Charlotte E. Rees, BSc (Hons), MEd, PhD, PFHEA, is Head of School, School of Health Sciences, College of Health, Medicine & Wellbeing, The University of Newcastle, and Adjunct Professor, Monash Centre for Scholarship in Health Education, Monash University.

References

- Davis C, King OA, Clemans A, Coles J, Crampton PES, Jacobs N, McKeown T, Morphet J, Seear K, Rees CE. 2020. Student dignity during work-integrated learning: a qualitative study exploring student and supervisors’ perspectives. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 25(1):149–172. doi:10.1007/s10459-019-09914-4.

- King O, Davis C, Clemans A, Coles J, Crampton P, Jacobs N, McKeown T, Morphet J, Seear K, Rees C. 2021. Dignity during work-integrated learning: what does it mean for supervisors and students? Stud High Educ. 46(4):721–736. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1650736.

- Monrouxe LV, Rees CE. 2017. Healthcare professionalism: improving practice through reflections on workplace dilemmas. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rees CE, Davis C, King OA, Clemans A, Crampton PES, Jacobs N, McKeown T, Morphet J, Seear K. 2020. Power and resistance in feedback during work-integrated learning: contesting traditional student-supervisor asymmetries. Ass Eval High Educ. 45(8):1136–1154. doi:10.1080/02602938.2019.1704682.

- Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. 2010. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances. BMC Med Educ. 10(1):12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-10-12.