ABSTRACT

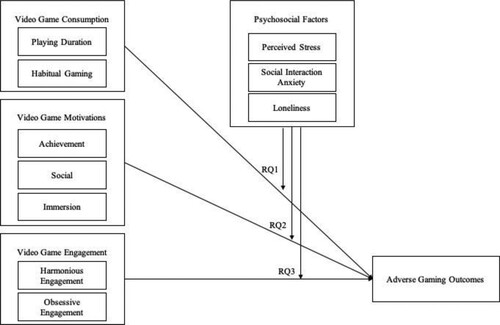

Based on the general assumption that even problematic behaviours are associated with an inherently health-promoting motivation to cope with unpleasant or unsatisfying life situations, the compensatory model of media use focuses on how psychosocial vulnerabilities moderate links between media behaviours and adverse outcomes. The present paper means to further develop this approach by exploring the moderating role of state- and trait-level factors (state: perceived stress; trait: social interaction anxiety and loneliness) on the relation between video game consumption (i.e. playing duration and habitual gaming), motivations (i.e. achievement, social, immersion), and engagement (harmonious and obsessive engagement) within a large-scale sample of mostly heavy gamers. Overall, results provided further evidence for the compensatory approach, with perceived stress emerging as a critical psychosocial factor that intensified positive and negative relations between several gaming behaviours and harmful outcomes. Moreover, our results reiterated the heuristic importance of intra- and interpersonally pressured (i.e. obsessive) engagement to explain adverse gaming outcomes as well as self-determined (i.e. harmonious) engagement as a potentially fruitful gateway toward more healthy gaming. These findings constitute solid empirical groundwork that may contribute to effective prevention and intervention methods against problematic gaming.

Over the past decades, media effects scholarship has demonstrated that playing video games can be considered a double-edged sword. On a positive note, many individuals seek to play video games as a pastime activity that enriches their lives with exciting challenges, narratives, or environments, thereby alleviating threats towards their basic psychological needs (e.g. Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006) or bad mood (e.g. Rieger et al. Citation2015). On the downside, however, research also found substantial evidence for a link between problematic gaming and both physical and psychological health issues (Männikkö et al., Citation2020), which culminated in the inclusion of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) into the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association Citation2013) as well as Gaming Disorder (GD) into the Eleventh Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization Citation2019). Both diagnosis instruments define problematic video game use upon a gradual loss of control and self-regulatory mechanisms that likely result in functional impairments (concerning an individual's professional, social, and relational life), eventually leading to addiction (Jo et al. Citation2019). This diagnostic institutionalisation of gaming disorder sparked an intense public debate (Schatto-Eckrodt et al. Citation2020) and harsh criticism from various researchers, who highlighted significant shortcomings of the underlying empirical findings (Griffiths et al. Citation2016) that may lead to an overpathologization of harmless (sometimes even beneficial) activities (Kardefelt-Winther et al. Citation2017). More specifically, it has been argued that such an overpathologization of gaming might create a moral panic through which a majority of healthy gamers may end up stigmatised, potentially culminating in health policies that may involve unnecessary treatments of false-positive cases (Aarseth et al. Citation2017). At best, overpathologization may discourage many people from playing games, effectively losing valuable opportunities for social engagement and personal empowerment (Bean et al. Citation2017).

Large-scale pre-registered studies demonstrated that relations between game consumption and psychological well-being follow a quadratic trend. Moderate usage was observed to be beneficial, while only intense gaming (particularly during weekdays, indicating conflicts with day-to-day obligations) was found detrimental (Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2017; Przybylski, Orben, and Weinstein Citation2019). On a similar note, Snodgrass, Lacy, and Cole (Citation2019) proposed that video games’ impact on well-being varies along a syndemic-syndaimonic continuum. Gaming may likely have a harmful (i.e. syndemic) impact when an individual's psychological well-being is already poor but a beneficial (i.e. syndaimonic) impact when it is good. Rather than being inherently beneficial or harmful, these findings suggest that video game effects are contingent upon people's engagement and their situational circumstances. Along similar lines, Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014a) conceptualised video games as easily accessible means that individuals utilise to help them cope with their daily lives. Extant literature has indeed demonstrated that video games serve as a versatile coping tool during distressing life situations (Iacovides and Mekler Citation2019) in both a proactive (e.g. by simulating emotionally challenging situations that they cannot experience in real life without taking significant risks; Villani et al. Citation2018) and a retroactive way (e.g. by offering a virtual environment, in which common real-life conditions are supplemented, superimposed, or even replaced with simulated and alternatively negotiated conditions; Consalvo Citation2009). Coping is also at the heart of individuals’ motivation for playing video games. The vast plurality of available video games offers a myriad of opportunities to satisfy their basic psychological needs (i.e. autonomy, competence, and social relatedness; Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006) or seek various gratifications (e.g. achievement/completion, challenge/arousal, social interaction, immersion/diversion/escapism; Hilgard, Engelhardt, and Bartholow Citation2013; Sherry et al. Citation2006; Yee Citation2006) that they may perceive to be lacking or are frustrated within their real-life (e.g. Bender and Gentile Citation2020; Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2019). Against this background, Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014a) postulated that positive and negative effects of video gaming are primarily a question of coping efficiency. Irrespective of how long individuals are playing, engagement in video games may efficiently or inefficiently serve its purpose as a coping tool.

The present study adopts this compensatory approach for investigating problematic video game use in a sample of game forum users. More specifically, our research focuses on how psychosocial vulnerabilities (or lack thereof) moderate the link between (a) video game consumption (i.e. how long do they play?), (b) video game motivations (i.e. why do they play?), as well as (c) different types of video game engagement (i.e. how do they play?) and adverse gaming outcomes. Our main empirical goal is to explore which indicators (under which situational circumstances) may distinguish between efficient and inefficient coping in order to contribute to the development of effective prevention methods against problematic gaming outside of the clinical context. As reviewed by King et al. (Citation2020), previous estimates for the prevalence of problematic gaming vary widely depending on which screening tool was deployed and which diagnostic cut-off value for present symptoms was determined. The authors further argue that alarming prevalence rates (such as, for instance, approximately 24% among Swedish adolescents in Vadlin, Åslund, and Nilsson Citation2018) likely emerge due to scope issues (i.e. covering phenomena that are not relevant for problematic gaming) and overpathologization of healthy behaviours (e.g. enthusiasm or self-regulation). More conservative estimates consider that between two to three percent of the population suffers from (internet) gaming disorder, that is, they surpass diagnostic cut-off values for existing screening tools (Stevens et al. Citation2020). This study disregards such cut-off values in favour of a continuous, subclinical view on problematic gaming tendencies.

Under the Open Science Framework's main principles, the present study is to be labelled exploratory due to a lack of pre-registered hypotheses and analysis plan. Therefore, our main theoretical goal is not to confirm whether or not the compensatory approach holds within a large sample of video game players but to lay a solid empirical groundwork that may be valuable for further developing the approach.

1. Model of compensatory video game usage

Predominant approaches towards problematic video gaming have highlighted correlations between individuals’ psychosocial vulnerabilities and harmful outcomes (Coyne et al. Citation2020; Griffiths, Kuss, and King Citation2012) while often neglecting to consider motivational factors that drive such damaging behaviours. Instead of thinking of intense gaming as just another compulsive behaviour, Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014a) associated problematic video game consumption (as a specific form of problematic media use) with an inherently health-promoting motivation. Based on human beings’ deeply rooted motivation to maintain psychological homeostasis, his compensatory model proposes that individuals are primarily engaging video games (or media, respectively) to cope with unpleasant or unsatisfying real-life situations. While video gaming may indeed be cathartic, increasing habituation of fleeting pleasures (without resolving the root cause, which may facilitate long-term happiness) might work against this compensatory function by intensifying existing (psycho-)social issues and their consequences (Gros et al. Citation2020) – in particular for individuals whose dispositions or current psychological state may complicate conflict resolution (e.g. maladaptive general coping strategies; Kökönyei et al. Citation2019). In other words, depending on an individual's situational circumstances (i.e. whether an individual is currently or generally susceptible to find themselves in an unpleasant life situation which they cannot easily manage), their gaming behaviour may serve as an efficient (i.e. problem-engaging) or inefficient (i.e. problem-disengaging) means to cope with a distressing situation (Bowditch, Chapman, and Naweed Citation2018). With this analytical perspective shift, direct relationships between individuals’ psychosocial vulnerabilities and problematic video gaming are taken out of the primary focus. Instead, psychosocial vulnerabilities are conceptualised as moderators between individuals’ gaming behaviour and related adverse outcomes. Based on previous research, we decided to focus on three pivotal psychosocial vulnerabilities: (1) stress, (2) social interaction anxiety, and (3) dispositional loneliness.

1.1. Stress

In the broadest sense, stress is defined as a psychological state that occurs when individuals perceive themselves in a demanding situation that they cannot adequately cope with (Lazarus Citation1999). If previously effective coping strategies do not bring sufficient relief, individuals often engage in activities that promise rapid diversion. While engaging in media during stressful periods may not be inherently troublesome, it can emerge as a serious problem if it prevents individuals from coping effectively with the underlying cause of their enhanced stress level. Previous research has shown that stress is positively related to problematic usage across different media, including video games (Canale et al. Citation2019), social networking sites (Hou et al. Citation2019), smartphones (Wolfers, Festl, and Utz Citation2020), or pornography (Borgogna, Duncan, and McDermott Citation2018). Extant studies investigating compensatory media use further evidenced that perceived stress is associated with problematic outcomes and moderates the link between media engagement and adverse outcomes. Concerning problematic smartphone use, disengaging motivations (i.e. using a smartphone for entertainment or escapism) were shown to be strongly associated with the severity of individuals’ problematic usage when those individuals reported high levels of stress, while a much weaker or even a beneficial effect was found for individuals who experienced low levels of stress (Shen and Wang Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2015). Similar effects were identified for video gaming. Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014b) demonstrated that individuals motivated by escapism to play video games experience more severe adverse gaming outcomes only when they are under high stress. Across media, the considerable multiplicity of findings suggests that stress should be regarded as a critical state-level vulnerability that amplifies links between media use and effects.

1.2. Social interaction anxiety

Theoretically situated within broader conceptualizations of social phobia, social interaction anxiety is described as a psychological trait that causes individuals to experience distress when interacting with other people (Mattick and Clarke Citation1998). Numerous studies have demonstrated that socially anxious individuals engage mediated social environments (such as social networking groups or cooperative multiplayer video games) to satisfy their need for belongingness as they provide them with more comfortable conditions for self-presentation and self-disclosure (e.g. Elhai, Levine, and Hall Citation2019; Martončik and Lokša Citation2016). However, any benefits provided by individuals’ engagement in mediated social environments (Colder Carras et al. Citation2017) may turn maladaptive when it prevents them from participating in face-to-face communication (Weidman et al. Citation2012).

Accordingly, social interaction anxiety has been highlighted as a psychosocial risk factor for problematic media use (e.g. Casale and Fioravanti Citation2015; Elhai, Levine, and Hall Citation2019; Mehroof and Griffiths Citation2010). However, research on a potentially moderating influence of social interaction anxiety is scarce. Shen et al. (Citation2019) found that state anxiety intensifies problematic smartphone use for individuals who primarily use their smartphone for entertainment and social purposes: While higher scores on entertainment and social interaction motivation was positively related to problematic smartphone use for highly anxious individuals, they had only a negligible correlation for individuals with low levels of anxiety. Similarly, maintaining intense parasocial relationships with YouTube personalities were revealed to be associated with problematic consumption of YouTube only for socially anxious individuals (de Bérail, Guillon, and Bungener Citation2019). Previous research has also demonstrated that socially anxious individuals whose internet use is primarily motivated by avoiding meeting other people in real life are more likely to suffer from depressive tendencies and low self-esteem. However, for individuals with low levels of social interaction anxiety, social avoidance motivation was associated with high psychological well-being (Weidman et al. Citation2012). In the video game context, Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014c) observed a similar moderation with social motivations associated with negative outcomes only for socially anxious individuals. Again (albeit with weaker evidence), these findings indicate that social interaction anxiety may be a critical trait that intensifies relations between media consumption and consequences.

1.3. Loneliness

Broadly defined, loneliness describes a psychological state characterised by ‘a discrepancy between one's desired and achieved levels of social relations’ (Perlman and Peplau Citation1981, 32). Both chronically and situationally lonely individuals tend to tap into mediated social environments to distract from or reduce this perceived discrepancy (Caplan, Williams, and Yee Citation2009; Song et al. Citation2014). Such an engagement may indeed help reduce feelings of loneliness by fostering meaningful social relationships, social support, and social capital (as shown in, e.g. Dienlin, Masur, and Trepte Citation2017; Karsay et al. Citation2019; Snodgrass, Lacy, and Cole Citation2019). However, previous research has also provided evidence that it can lead individuals into a vicious circle with increasingly problematic media usage and deteriorating psychological well-being (Kim, LaRose, and Peng Citation2009; Lemmens, Valkenburg, and Peter Citation2011; Snodgrass et al. Citation2018). Playing video games has been hypothesised to have a dualistic effect on psychosocial factors as it can both expand and restrict meaningful social contacts (Williams Citation2018).

In all of these studies, chronic or situational loneliness has been considered either a predictor or consequence of intense media consumption or adverse outcomes (or as a mediator between those two and another concept, respectively) rather than a moderator between media use and adverse outcomes. Except for Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014c), who reported a non-significant interaction between social motivation and loneliness when linked with negative gaming outcomes, we are not aware of any study asking explicitly whether individuals’ loneliness may moderate the relation between media consumption, motivations, or engagement forms and negative outcomes. The present study intends to fill this gap.

2. Current study

Despite continuing criticism concerning its diagnostic value for problematic video gaming (e.g. Kneer and Rieger Citation2015), playing duration is still a focal point of academic and public attention (e.g. Petry Citation2019). Large-scale studies have indeed demonstrated that very long hours of video gaming may hurt individuals’ psychological well-being (Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2017; Przybylski, Orben, and Weinstein Citation2019). Nevertheless, researchers have stressed that highly intense video gaming should be differentiated into problematic and highly engaged (but mostly harmless) video gaming (e.g. Billieux et al. Citation2019). According to this particular research line, intense video game usage typically goes hand in hand with euphoria directed toward the game content (that does not break off once someone has stopped playing) and an intrinsic desire to spend more time playing. Problematic video gaming, however, is assumed to start when it conflicts with an individual's everyday life and they lost control over it – thus, qualifying some of the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-5 and ICD-11 (Billieux et al. Citation2019). While said conflicts in everyday life may occur naturally with very long playing time, deficient self-regulation is associated with strong habitual gaming (LaRose, Lin, and Eastin Citation2003). Gaming habits can be conceptualised as relatively stable mental links between video game usage and its expected immediate outcomes that are acquired upon repetition and activated through internal and external cues, potentially replacing intentions as a primary determinant of gaming behaviour (Hartmann, Jung, and Vorderer Citation2012; LaRose Citation2010). Based on the previous research on compensatory media use described above, it is conceivable that individuals with psychosocial vulnerabilities are more likely to slip into problematic gaming and experience adverse outcomes from intense and habitual video game consumption than individuals who are less stressed, socially anxious, or lonely – irrespective of why and how they end up playing (Gros et al. Citation2020). Our first research question, therefore, focuses on testing Kardefelt-Winther's compensatory model broadly with video game use as a coarse-grained parameter associated with adverse gaming outcomes:

RQ1: How will the link between individuals’ video game consumption and adverse gaming outcomes be moderated by their (a) perceived stress, (b) social interaction anxiety, and (c) loneliness?

A significant portion of research on problematic video gaming highlighted the crucial role of escapism as a maladaptive motivation that is linked to poor well-being (e.g. American Psychiatric Association Citation2013; Kaczmarek and Drążkowski Citation2014), in particular for psychosocially vulnerable individuals (Di Blasi et al. Citation2019; Kardefelt-Winther Citation2014b). While escapism has mostly been associated with immersion motivation, it is not necessarily restricted to it and may also be linked to achievement and social motives (Snodgrass et al. Citation2013). Hence, it is not surprising that both achievement and social motivation have likewise been found to mediate the link between video game usage and adverse outcomes (Chang, Hsieh, and Lin Citation2018). On the upside, high levels of social motivation (even if motivated by escapism) can result in individuals establishing meaningful social contacts within video games, which alleviate adverse outcomes (Colder Carras et al. Citation2017; Snodgrass et al. Citation2018) – most of all, again, for individuals with psychosocial vulnerabilities (Kardefelt-Winther Citation2014c). More generally, Deleuze et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that all three higher-level motivations are associated with both problematic and unproblematic (i.e. highly engaged) video gaming. Because of this dualistic pattern of effects, it is vital to examine how different psychosocial vulnerabilities influence the relation between all three higher-level video game motivations and negative gaming outcomes. Following the compensatory model's logic, individuals with psychosocial vulnerabilities may be more likely to experience negative outcomes when they are highly motivated by either of these three motivations, as all of them may engage them in inefficient coping. Then again, in particular, individuals with psychosocial problems may potentially benefit most from highly motivated video gaming as long as it efficiently helps them to cope with everyday life issues. To examine whether each of the three higher-level motivations’ association with negative gaming outcomes is influenced by psychosocial factors (i.e. whether psychosocial factors determine its coping efficiency), our second research question goes beyond how much time individuals have spent with video games and tests the compensatory approach against a motivational background:

RQ2: How will the link between individuals’ motivations to play video games (achievement, social, immersion) and adverse gaming outcomes be moderated by their (a) perceived stress, (b) social interaction anxiety, and (c) loneliness?

Although it was initially designed to apply to any given activity, several researchers have established this dualistic model of passion for the study of problematic video gaming (e.g. Kneer and Rieger Citation2015; Lafrenière et al. Citation2009; Przybylski et al. Citation2009; Utz, Jonas, and Tonkens Citation2012). Similar to findings on other activities, the constitutive effect pattern held for video gaming as well. Previous studies have consistently found that harmonious engagement in video games is positively linked to indicators of beneficial gaming outcomes (e.g. life satisfaction; Lafrenière et al. Citation2009; online friendship quality; Utz, Jonas, and Tonkens Citation2012), whereas obsessive engagement is related to harmful outcomes (e.g. physical issues; Lafrenière et al. Citation2009; lack of offline friendships; Utz, Jonas, and Tonkens Citation2012). Notably, concerning compensatory video gaming, Przybylski et al. (Citation2009) showed that individuals’ obsessive passion for video games and their playing duration interact with each other in their relationship with psychological well-being. For individuals who scored low on obsessive passion, increasing playing time was positively associated with their well-being; the opposite effect was found for individuals with high levels of obsessive passion. Similarly, obsessive engagement in video games may interact with psychosocial vulnerabilities to further reinforce difficulties in everyday life, while it might be less problematic for psychosocially stable individuals. As previous research has revealed that harmonious engagement in video games is associated with beneficial outcomes (e.g. gaining social capital; Perry et al. Citation2018; positive affect and self-realisation; Lafrenière et al. Citation2009), it appears plausible to assume a reverse, mitigating influence on negative gaming outcomes. In other words, harmonious engagement in video games may be most efficient in coping with life issues for people with psychosocial vulnerabilities. To test whether psychosocial factors affect the coping efficiency of harmonious engagement and the coping inefficiency of obsessive engagement, we posed a third research question:

RQ3: How will the link between different types of individuals’ video game engagement (harmonious and obsessive) and adverse gaming outcomes be moderated by their (a) perceived stress, (b) social interaction anxiety, and (c) loneliness?

3. Method

All study materials (including survey files, data files, and analysis scripts and outputs) are available online: https://osf.io/qye5j/. The study procedure conformed with ethics guidelines given by the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.1. Participants

Participants were recruited via online invitation distributed (with the respective moderators’ approval) across a great variety of video game-related forums at reddit.com and GameFAQs.com (see OSF material for a complete list). Instead of limiting the sample to players of a single video game or a discrete genre (that may include structural characteristics which enhance the likelihood of problematic gaming), we decided to spread our survey across various forums to improve generalizability. Accordingly, participants named hundreds of different video games as their current favourite game (see OSF material for a complete list).

Before analysis, we iteratively excluded all participants (a) who did not complete the survey (irrespective of whether they answered all items; n = 3742, 43.90%), (b) who did not state how old they were at the time of completion or who were under 18 years (i.e. not eligible to participate; n = 1045, 21.86%), and (c) who did not answer at least one item from each scale (n = 81, 2.17%). In total, 3655 participants (age M = 25.22, SD = 6.68, range: 18–62 years)Footnote1 met the criteria to be included in the final sample. Due to a well-known over-representation of men in online gaming forums (Griffiths et al. Citation2017), the majority of participants identified themselves as male (n = 3139, 85.88%) compared to self-identified female participants (n = 482, 13.19%) and participants who did not specify their sex (n = 34, 0.93%). Participants varied substantially about how many hours they are currently playing during a typical week (M = 35.24, SD = 24.99, Mdn = 29, range: 0–140 hours).

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Psychosocial factors

We assessed participants’ current perceived stress level via the ten-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein Citation1983), in which they specified on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always) how often they appraised their lives as stressful during the last month (sample item: ‘In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?’). All items were averaged to create an index with good internal reliability (α = .88).

Participants’ anxiety about interacting with others was measured using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (Heimberg et al. Citation1992). The scale consists of 19 items, asking participants whether several statements applied to them in social situations (e.g. ‘I find myself worrying that I won't know what to say in social situations’.) on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all; 5 = very true). Notably, we decided to modify the wording of one item from ‘I have difficulty talking to attractive persons of the opposite sex’ to ‘I have difficulty talking to attractive persons of the desired sex’ to prevent excluding non-heterosexual participants. The averaged index showed excellent internal reliability (α = .93).

We measured participants’ loneliness via the eight-item short version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Hays and DiMatteo Citation1987), asking participants to state how often they feel isolated from other people with items such as ‘There is no one I can turn to’ using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = always). Again, we averaged all items to create an index with good internal reliability (α = .87).

3.2.2. Negative gaming outcomes

Conceptualising adverse gaming outcomes and establishing a suitable measurement represent a pivotal challenge to the academic discourse on problematic video gaming (Kardefelt-Winther et al. Citation2017). For this study, we used a 5-item measure proposed by Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014b) that focuses on physical and relational outcomes that are generally accepted as harmful within the research community (e.g. sleep deprivation, loss of relationships, or job opportunities, Kardefelt-Winther Citation2015). Participants were asked to indicate how frequently they experience situations such as ‘I sometimes lose sleep because of the time I spend playing video games’ on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = never, 7 = always). All items were averaged, creating an index with acceptable reliability (α = .73).

3.2.3. Video game consumption

Instead of focusing merely on playing time, we employed two different measurements to cover different facets of participants’ video game consumption. First, we asked them to estimate how many hours they had spent playing video games on both a typical weekday and a typical day on the weekend during last month as a measurement for participants’ current engagement in video gaming. We created an index for a typical week for statistical analyses, adding up playing duration on weekdays (multiplied by five) and on the weekend (multiplied by two).

As a second indicator, we additionally measured participants’ habitual gaming behaviour via an adapted version of the twelve-item Self-Report Habit Index (Verplanken and Orbell Citation2003). For each item, participants specified how much they agree or disagree with statements introduced by ‘Playing video games is something … ’ (e.g. ‘ … I do automatically’) on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 7 = completely agree). Due to low item-scale correlations (r < .2), four items (‘ … I do frequently’, ‘ … that belongs to my [daily, weekly, monthly] routine’, ‘ … that's typically me’, and ‘ … I have been doing for a long time’) were removed before calculating an averaged index with good internal reliability (α = .86).

3.2.4. Video game motivations

To measure participants’ motivation to play video games, we used a 13-item adaption from the Game Play Motivations Scale (Yee Citation2006). The scale operationalises all three higher-level motivations: achievement motivation (six items; e.g. ‘Mastering the game as fast as possible’), social motivation (four items; e.g. ‘Chatting with other players’), and immersion motivation (three items; e.g. ‘Escaping from the real world’). Items were presented with one of three different instructions. For some items,Footnote2 participants were asked how important these motivations are for them (5-point Likert scale: 1 = not important at all; 5 = extremely important), while for others, they stated how much they enjoy doing them (5-point Likert scale: 1 = not enjoyable at all; 5 = tremendously enjoyable), or how often they play for particular reasons (5-point Likert scale: 1 = never; 5 = always). One item of the immersion factor (i.e. ‘to relax from the day's work?’) had to be excluded due to a low correlation with the rest of the factor (r = .17). The internal consistencies of the three averaged indices ranged from slightly questionable to good (achievement motivation: α = .68; social motivation: α = .83; immersion motivation: ρ = .68).

3.2.5. Video game engagement

The 14-item Passion Scale (Vallerand et al. Citation2003) was used to measure participants’ engagement with video gaming. Corresponding with its theoretical background, the scale differentiates between harmonious and obsessive engagement. Both subscales consist of seven items that ask participants how much they agree or disagree with statements such as ‘The new things that I discover with this activity allow me to appreciate it even more’, indicating harmonious engagement or ‘I have a tough time controlling my need to do this activity’ indicating obsessive engagement using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = fully disagree, 7 = fully agree). Both subscales’ items were averaged, resulting in two indices with acceptable alpha scores for harmonious engagement (α = .72) and good internal reliability for obsessive engagement (α = .84).

3.3. Analytical strategy

To answer our research questions, we tested a series of increasingly complex hierarchical regression models for adverse gaming outcomes. The baseline regression model included each of the three psychosocial factors (i.e. stress, social interaction anxiety, and loneliness) and participants’ age as an additional covariate (to control for the impact of varying foci across different life stages that could affect problematic gaming; Festl, Scharkow, and Quandt Citation2013). Of note, participants’ gender was not included as a covariate due to the extreme imbalance within the sample. In the second model, video game consumption parameters (i.e. playing duration and habitual gaming) were added to the model as both a linear and a quadratic predictor (following findings by, e.g. Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2017). Interaction terms between video game consumption parameters and each of the three psychosocial factors were entered for model 3a (interaction term with linear predictors) and model 3b (interaction terms with quadratic predictors).

Research questions 2 and 3 addressed whether psychosocial vulnerabilities moderate the relations between individuals’ motivation to play video games as well as their form of engagement and adverse gaming outcomes. To investigate these research questions, we decided to calculate two separate regression models. In model 4a, we entered the three higher-level gaming motivations (i.e. achievement motivation, social motivation, immersion motivation) into model 2, which was aimed at the main effects of both video game usage parameters. A similar procedure was used for model 4b, with harmonious and obsessive gaming engagement added to the regression formula of model 2. Subsequently, interaction terms with each psychosocial factor were entered in model 5a (interaction terms with video game motivations) and model 5b (interaction terms with engagement forms). Each interaction term is interpreted and plotted with gaming behaviours as main predictors and psychosocial vulnerabilities as moderators (see supplemental material for an inverted interpretation). To minimise non-essential multicollinearity, each predictor included in either a non-linear regression or an interaction term was grand mean-centered before analysis.

However, it must be noted that the commonly accepted interpretation of significance tests (i.e. p < .05 suggesting statistical relevance of an effect) loses practical meaning with very large sample sizes. Although we report these standard inferential statistics in the supplemental material, we want to emphasise that our interpretation of the results is primarily based on each regression coefficient's effect sizes (i.e. explained variance). Statistical significance was applied as a secondary criterion to indicate statistical but not necessarily practical relevance. In other words, statistically significant effects were further examined with regard to their effect size to determine their meaningfulness. Effect sizes were calculated with the relaimpo package in R (Grömping Citation2006) using the lmg methodFootnote3 (Lindeman, Merenda, and Gold Citation1980).

4. Results

Descriptive information and zero-order correlations are displayed in . As between-predictor correlations were consistently low-to-moderate, multicollinearity issues could be ruled out. Although our data revealed that indices for obsessive engagement and adverse gaming outcomes were left-skewed just as harmonious engagement turned out right-skewed, each of these three variables did not show durable floor or ceiling effects.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations.

4.1. Main analysis

Our baseline regression model, including participants’ scores for stress, social interaction anxiety, and loneliness, as well as their age, explained 12.87% of the variance of their negative gaming outcomes score. Participants’ stress level (β = .20) turned out to be the strongest predictor with approximately 5.18% explained variance, followed by loneliness (β = .12, R2 = .037) and social interaction anxiety (β = .08, R2 = .029). Interestingly, only perceived stress demonstrated a practically relevant main effect (R2 ≥ .04; Ferguson Citation2009).

4.1.1. Video game consumption

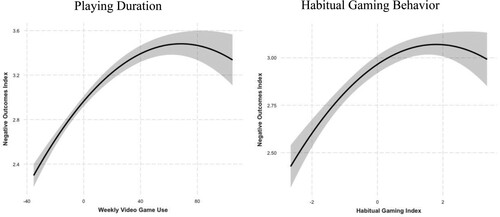

After introducing video game consumption (operationalised via playing duration and habitual gaming) as both a linear and a quadratic predictor to the regression formula, model 2 explained 21.77% of the criterion's variance. Playing duration and habitual gaming demonstrated both linear and quadratic trends in explaining negative gaming outcomes, with positive coefficients for the linear predictors (i.e. suggesting that higher scores on either of these parameters mean higher negative gaming outcome scores) and negative coefficients for the quadratic predictors (i.e. indicating concave relations between predictors and criterion). As evident in , both non-linear trends can be considered logarithmic, as higher playing duration and stronger habitual gaming are associated with a diminishing increase of negative gaming outcomes. Adding up the linear and the quadratic predictors, playing duration accounted for 7.25% explained variance (linear predictor: β = .33, R2 = .060, quadratic predictor: β = −.15, R2 = .012) and habitual gaming explaining 3.52% of the criterion (linear predictor: β = .15, R2 = .030, quadratic predictor: β = −.07, R2 = .005). Before considering why and how participants play video games, our results demonstrated that playing time stands out as a positive predictor of negative gaming outcomes, although its increasing influence slows down at very heavy gaming.

Figure 2. Adverse gaming outcomes regressed on playing duration and habitual gaming behaviour, quadratic models.

Note: Both predictors are mean-centered. Grey colour gradients show the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval. In both cases, the y-axes are adjusted to reflect the quadratic trend.

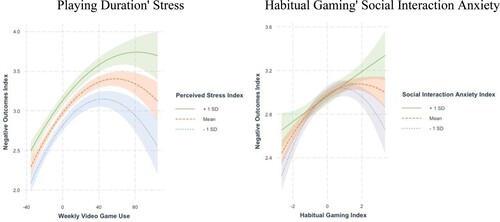

Entering interaction terms between video game consumption and psychosocial factors added little to the regression models’ overall explained variance. While model 3a (which included interaction terms with linear consumption predictors) explained 23.05% variance, model 3b (which included interaction terms with quadratic consumption predictors) accounted for 22.76% of the variance in negative gaming outcomes. Concerning RQ1, we found four significant interaction effects. Both the linear and the quadratic relation between participants’ playing duration and negative gaming outcomes was moderated by perceived stress (β = .07, R2 = .006 and β = .07, R2 = .004, respectively); the linear relationship between playing duration and negative outcomes was also moderated by loneliness (β = .05, R2 = .004); and the quadratic trend of habitual gaming was moderated by social interaction anxiety (β = .10, R2 = .003). Notably, effect sizes are typically rather small for interaction effects (in particular, compared to main effects). According to ‘optimistic’ interpretation guidelines proposed by Kenny (Citation2018), each of the four interaction effects may be considered small.

In line with the compensatory model, higher scores on psychosocial vulnerabilities intensified the link between video game consumption and adverse outcomes (see ). As displayed in , both interaction effects with quadratic predictors further showed the existence of local maxima for participants with medium or low psychosocial vulnerability, suggesting that extremely long play durations and highly habitual gaming may be associated with less problematic outcomes than comparably shorter (but generally long durations) and moderately habitual gaming. It should be noted, however, that these patterns should be considered with utmost caution. Not only are these effect patterns based on very few extreme cases (resulting in higher standard errors, as evident in ), but these few cases are also highly susceptible to self-selection bias when using convenient sampling methods. Nonetheless, our data provide a preliminary answer to RQ1: All three psychosocial vulnerabilities, albeit weakly, moderated distinct links between individuals’ video game usage and adverse outcomes. They do so consistently in a way that more vulnerable individuals experience more harmful outcomes.

Figure 3. Adverse gaming outcomes regressed on playing duration and habitual gaming behaviour, quadratic models. Coloured lines represent simple slopes using perceived stress and social interaction anxiety as moderators.

Note: Both predictors are grand mean-centered. Colour gradients show the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval. In both cases, the y-axes are adjusted to reflect the quadratic trend.

4.1.2. Video game motivation

In model 4a, we added all three higher-order gaming motivations (i.e. achievement motivation, social motivation, immersion motivation) to the linear and quadratic video game usage predictors. This regression model explained 27.00% of the variance of negative gaming outcomes. Both achievement (β = .19, R2 = .050) and immersion motivation (β = .14, R2 = .044) turned out as practically relevant predictors; social motivation (β = .01, R2 = .004) demonstrated no such explanatory value. Controlling for gaming motivations weakened playing duration's positive link to negative outcomes (linear predictor: β = .26, R2 = .046; quadratic predictor: β = −.12, R2 = .010).

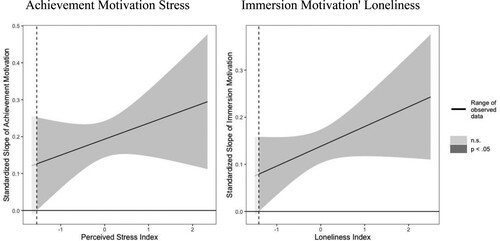

In the next step, we included interaction effects between each gaming motivation and each psychosocial factor in model 5a, which explained 27.62% of the criterion's variance. The results showed two significant interactions. The correlation of achievement motivation was moderated by perceived stress (β = .04, R2 = .002) as well as immersion motivation by loneliness (β = .04, R2 = .002). As displayed in , both interaction effects align with the compensatory approach. The positive relationship between their achievement/immersion motivation and negative gaming outcomes increases for participants with higher psychosocial vulnerabilities. These findings give a preliminary answer to RQ2: Perceived stress moderated the link between individuals’ achievement motivation and negative gaming outcomes just as loneliness moderated the link between their immersion motivation and these outcomes.

Figure 4. Johnson-Neyman plots for moderations of achievement motivation and adverse gaming outcomes by stress and immersion motivation and adverse gaming outcomes by loneliness.

Note: Grey colour gradients show the upper and lower boundaries of the beta coefficients’ 95% confidence interval. The x-axis is trimmed to the variables’ observed range.

4.1.3. Video game engagement

In parallel with the previous two models, we included both harmonious and obsessive engagement to the linear and quadratic video game consumption predictors in model 4b, as well as interaction terms for both forms of engagement with each psychosocial vulnerability in model 5b. In total, model 4b explained 32.97% of the variance of negative gaming outcomes. Most of this additional variance can be attributed to obsessive passion's connection with negative gaming outcomes (β = .41), which accounted for 16.49% explained variance. Harmonious engagement was negatively associated with harmful outcomes to a practically irrelevant extent (β = −.11, R2 = .005). Again, introducing engagement weakened the positive link to playing duration (linear predictor: β = .22, R2 = .042, quadratic predictor: β = −.12, R2 = .009).

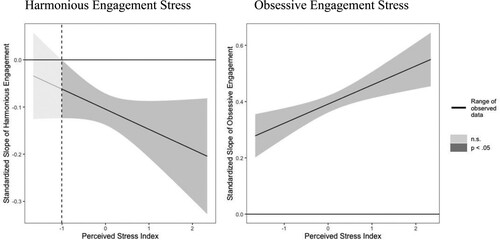

Once interaction terms were added, model 5b accounted for 33.74% of the variance of negative gaming outcomes. Out of the three psychosocial factors, only perceived stress demonstrated itself as a significant moderator. These interactions followed a pattern that can be considered in line with the compensatory approach (see ). Obsessive engagement was related to more harmful outcomes for stressed participants (β = .07, R2 = .004). The opposite was revealed for harmonious engagement: Higher stress levels were linked to less negative gaming outcomes as participants stood out as increasingly psychosocially vulnerable (β = −.04, R2 = .003). Thus, RQ3 can be answered preliminary by stating that stress moderated the relation between individuals’ video game engagement: Obsessive engagement was found even more detrimental to individuals’ health when they experience high levels of stress; harmonious engagement, however, was most beneficial for stressed individuals.

Figure 5. Johnson-Neyman plots illustrating moderations of harmonious engagement and obsessive engagement and adverse gaming outcomes by stress.

Note: Grey colour gradients show the upper and lower boundaries of the 95% confidence interval of the beta coefficients. The x-axis is trimmed to the variables’ observed range.

4.2. Supplemental analysis

Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014b) suspected that problematic consequences related to compensatory gaming might be concealed when investigated within a representative sample as a vast majority of players do not experience any serious adverse outcomes. Instead, it was suggested that compensatory gaming should be investigated among heavy players. Although our sample must not be considered representative but heavily skewed toward players who engage in intense gaming (most notably illustrated by an average weekly playing time of 35.24 hours, a median of 29 hours, and the engagement in gaming community), we conducted a supplemental analysis intended to follow Kardefelt-Winther's argument. Accordingly, we reiterated our analysis procedure for two subsamples: light-to-moderate and heavy gamers.

This supplemental analysis showed that regression models had weak explanatory value for negative gaming outcomes for light-to-moderate gamers, while its results mirrored the original analysis for heavy gamers. Full results are available online: https://osf.io/qye5j/. These effect patterns indicate that the original full sample analysis did not underestimate compensatory effects (arguably because our sample consisted mainly of heavy gamers).

5. Discussion

Kardefelt-Winther's (Citation2014a) model of compensatory media use proposes that media consumption should be conceptualised as a (more or less efficient) coping reaction, which most likely emerges as inefficient for psychosocially vulnerable individuals. The present paper explored this underlying premise for video games, utilising a broad approach that examined how different consumption parameters (i.e. how long, why, and how individuals’ play video games) are related to harmful outcomes under varying psychosocial conditions (i.e. stress, social interaction anxiety, dispositional loneliness). For that purpose, a large-scale online survey was conducted for which we recruited a convenience sample of gamers from various gaming-related forums. Results showed support for the compensatory model; yet, the overall picture is best described as polyvalent. Perceived stress emerged as critical psychosocial vulnerability intensifying links between several parameters and harmful outcomes, while social interaction anxiety and loneliness only influenced certain isolated relations. More specifically, our analyses replicated previous research that found statistically positive associations between adverse outcomes and extended playing time (e.g. Przybylski and Weinstein Citation2017), habitual gaming (e.g. Hartmann, Jung, and Vorderer Citation2012), achievement motivation (e.g. Chang, Hsieh, and Lin Citation2018), immersion motivation (e.g. Kneer and Rieger Citation2015), and obsessive engagement (e.g. Przybylski et al. Citation2009), as well as a statistically negative correlation with harmonious engagement (e.g. Lafrenière et al. Citation2009) – with each of which being moderated by one or more of participants’ psychosocial vulnerabilities. Supplemental analysis separating light-and-moderate players and heavy players into subsamples suggested that most compensatory effects are most pronounced among heavy gamers.

Based on the premise that individuals’ media consumption is embedded in their global effort to cope with everyday life issues, the model of compensatory media use suggests that psychosocially vulnerable individuals are more at risk of exercising maladaptive media-driven coping (Kardefelt-Winther Citation2014a). More precisely, these psychosocially vulnerable individuals are more likely to engage video games searching for short-term pleasure, which may distract them from easing existing hardships. Such psychosocial vulnerabilities include both states (i.e. temporary psychological conditions) and traits (i.e. relatively stable psychological characteristics). Our data indicate that traits, such as dispositional loneliness and social interaction anxiety, can emerge as relevant psychosocial factors. However, perceived stress, a state-level vulnerability, turned out to be a more reliable moderator for the relation between gaming and harmful outcomes. This predominance of state- over trait-level vulnerabilities broadly aligns with extant findings on their relative explanatory value for health-related indicators: Dispositional traits are indeed associated with health-related outcomes to a considerable degree, but this link often gets minimised once psychological states are added to the equation (e.g. Howell et al. Citation2017). For cross-sectional inquiries such as the present one, less salient psychosocial dispositions may be less vital once individuals’ current mental condition is taken into account. In the current study, neither higher scores for social interaction anxiety nor dispositional loneliness appeared to make individuals considerably vulnerable to inefficient gaming-driven coping. On the other hand, perceived stress does seem to amplify the link between gaming and negative outcomes – both in a positive or negative direction. Investing plenty of time into video games, striving vigorously toward becoming a highly advanced player, or feeling high internal or external pressure to engage in gaming may not necessarily be an immediate cause for concern if individuals are currently living a life that is mostly free of stress (e.g. during the holiday season or vacation). However, it might become concerning when individuals are already experiencing severe stress in their daily lives (e.g. during final exams, relationship crises, after loss of socioeconomic status). Highly self-determined (i.e. harmonious) gaming may even be desirable in a stressful life situation. It provides people with a refreshing and satisfying break that can help them resolve their underlying issues (Lalande et al. Citation2017). These findings send a strong signal to scholars, health professionals, and public policymakers not to approach gaming behaviours as inherently and uniformly harmful (or beneficial) but instead contextualise their concerns (or hopes) by considering individuals’ psychosocial conditions. This call for a more robust psychosocial contextualisation further challenges conventional screening tools’ diagnostic validity for problematic video game use. Aside from concerns about overpathologization (cf. King et al. Citation2020), asking people whether or not there have been periods when they were consistently thinking about games, temporarily lost control over their gaming, or wanted to escape negative feelings with it during the last year (Lemmens, Valkenburg, and Gentile Citation2015) does not account for under which psychosocial conditions these symptoms may have emerged during these periods. Each of these possibly problematic symptoms may have appeared, for the sake of argument, during periods of very low stress, which may mitigate their assumed predictive value while reinforcing potential overpathologization of healthy (or at least not considerably harmful) video game use. Accordingly, our findings may be understood as another call for improving screening tools for problematic gaming in order to avoid overpathologization.

Notably, our cross-sectional study design addressed trait- and state-level vulnerabilities in parallel (i.e. without a conceptual hierarchy). Psychosocial traits may precede state-level vulnerabilities (Maroney et al. Citation2019). Based on zero-order correlations between trait- and state-level factors, more severe social interaction anxiety and loneliness may have led to enhanced levels of perceived stress (e.g. via lacking social support that may alleviate stress; Karsay et al. Citation2019), thus manifesting their respective moderating influence on the link between gaming behaviour and outcomes indirectly over time. This study's methodology does not allow testing such a dynamic understanding. However, future longitudinal work may disentangle the various sources of perceived stress to catch a glimpse into the underlying dynamics of psychosocial vulnerabilities and their consequences.

Since our study design included individuals’ consumption and their motivation and engagement type, our analysis was able to distinguish discrete effects across each of these different concepts. Despite playing duration, achievement motivation, and immersion motivation emerging as weak but practically relevant factors (replicating extant findings on these parameters), obsessive engagement stood out as the by far most influential phenomenon to explain adverse outcomes – in particular among people who are currently suffering from high levels of stress. This result suggests that individuals who engage in video games compulsively because of intra- and interpersonal pressure are more likely at risk of experiencing harmful consequences. Beyond once again demonstrating the explanatory value of obsessive engagement (above individuals’ consumption parameters and motives; Kneer and Rieger Citation2015; Przybylski et al. Citation2009; Tóth-Király et al. Citation2019), its association with problematic outcomes, together with the opposing beneficial impact of harmonious engagement among psychosocially vulnerable people, may serve as a good starting point for promising prevention and intervention methods. Accordingly, actions would focus primarily on inducing a cognitive and behavioural shift from obsessive toward harmonious engagement. Instead of forcing passionate gamers to break with their preferred coping strategy and denounce an essential part of their identity (i.e. treating gaming as the root cause of existing health problems), this approach would train individuals’ self-regulation skills and promote a self-determined way of playing video games (i.e. treating gaming as a symptom of and part of the solution for more general issues). This slightly soft interventionist strategy might be preferable to harsher (i.e. more restrictive) strategies for at least two reasons: First, longitudinal research has consistently shown that problematic video gaming is not very durable but occurs most often only temporarily (Rothmund, Klimmt, and Gollwitzer Citation2016; Scharkow, Festl, and Quandt Citation2014). Harsh interventionist approaches (imposed most likely by parents or other legal guardians) might create severe relational conflicts about something that most likely will resolve naturally over time. Secondly, more restrictive approaches had predominantly been found effective short-term (and with considerable heterogeneity), as beneficial effects often diminished after only a few months (Stevens et al. Citation2019). It is conceivable that a gentle corrective approach that focuses on altering individuals’ engagement without overpathologizing it may prove more effective in the long run. Future interventionist studies should experimentally vary the restrictiveness of therapeutic measures to find the most beneficial approach to answering this open question.

The current study is subject to several limitations. Although we could recruit a large-scale sample of various gamers from game forums that may be considered superior to standard student samples recruited in introductory university courses, it must be highlighted that it is nevertheless a convenience sample. It should, therefore, be noted that male and younger heavy core (i.e. non-mobile) players were overrepresented in our data. While such an overrepresentation of particular groups of players reduces the generalizability of our findings to the general population (as it massively exaggerates the prevalence of both heavy players and harmful outcomes), it can be argued with Kardefelt-Winther (Citation2014b) that compensatory media consumption might be best investigated with a focus on highly engaged individuals whose primary coping strategy may include gaming. In other words, non-representativeness may be acceptable to reduce the risk of overlooking psychological mechanisms in the target group. However, we have to acknowledge that the user structure of these forums is heavily biased towards Western countries, such that common generalizability issues associated with WEIRD (i.e. western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) sampling (cf. Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan Citation2010) are present. Additionally, our measures were based exclusively on self-reports, making them vulnerable to intentional and unintentional bias. As noted by Kneer et al. (Citation2012), social desirability bias may be more pronounced in online surveys about (problematic) video gaming due to players’ attempts to implicitly or explicitly protect their gamer identities against supposedly hostile intentions. To prevent misconceptions of this sort, we placed particular emphasis on transparency, disclosing our research intentions in much detail to both forum admins and potential participants. Lastly, as a consequence of our sample size, we decided to prioritise practical over statistical significance. Naturally, this decision comes with a price. In contrast to the widely accepted 5% significance threshold, benchmarks on what should be considered a practically relevant effect are much less acknowledged and often vary depending on the preferred reference (which may be particularly true for moderation effects of continuous predictors). However, irrespective of the reference, it is important for us to stress that most of our practically relevant effects are still regarded as small-to-moderate in size. Substantial implications should be drawn with caution and only after pre-registered confirmatory evidence had been obtained.

6. Conclusion

The present study's main theoretical contribution lies in establishing a solid foundation for the compensatory model of media use for video games based on a large-scale sample of primarily highly engaged gamers and covers their consumption, motivation, and engagement types. Most notably, our findings indicate that obsessive engagement in video games may play the most pivotal role in explaining harmful consequences in general (compared to individuals’ consumption or motivation) and constitute the most evident indicator of inefficient coping during stressful periods. From a practical point of view, our data further suggest that an improvement in coping efficiency may be most feasible by promoting a shift from maladaptive obsessive engagement to beneficial harmonious engagement (i.e. from internally/externally controlled to self-determined engagement) as such a shift may not necessarily jeopardise individuals’ identity as gamers. Considering that video games’ popularity is still on the rise (currently culminating in a certain level of ubiquity due to mobile trends), it may be critical to accept video games as part of the solution for problematic gaming rather than as its heart.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Since we used open-ended format items to assess participants’ age, few participants opted for answering in vague terms, such as ‘mid-twenties’ or ‘late twenties’. To include those participants in the final sample, we replaced these vague terms with numerical expressions (e.g. 25 for ‘mid-twenties’ or 29 for ‘late twenties’).

2 The following items were evaluated according to their importance: ‘mastering the game as fast as possible’, ‘acquiring rare achievements that most players will never have’, ‘becoming skilful’, ‘accumulating resources, items or money’, ‘being well-known in the game’, and ‘escaping from the real world’; to their enjoyment: ‘being part of a serious, competitive/goal-oriented group’, ‘helping other players’, ‘getting to know other players’, ‘chatting with other players’, and ‘being part of a friendly, casual group’; and to their frequency: ‘so you can avoid thinking about some of your real-life problems or worries’ and ‘to relax from the day's work’.

3 The lmg method calculates each predictor's relative importance by averaging individually explained variance over each possible ordering in the formula. For regression models that include many predictors, this procedure requires a computational effort that exceeds standard computer memory units. This problem occurred in the present study for each regression model that included interaction terms (i.e. models 3a, 3b, 5a, and 5b). We addressed this computational issue by using reduced regression models for estimating the relative importance, in which we iteratively removed the weakest interaction effects from the regression formula until the required computational effort fell below the available RAM. The final alternative regression models (including their potential error in individually explained variance) are documented in the supplemental material.

References

- Aarseth, E., A. M. Bean, H. Boonen, M. Colder Carras, M. Coulson, D. Das, J. Deleuze, et al. 2017. “Scholars’ Open Debate Paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder Proposal.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 6 (3): 267–270. doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.088.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bean, A. M., R. K. L. Nielsen, A. J. van Rooij, and C. J. Ferguson. 2017. “Video Game Addiction: The Push to Pathologize Video Games.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 48 (5): 378–389. doi:10.1037/pro0000150.

- Bender, P. K., and D. A. Gentile. 2020. “Internet Gaming Disorder: Relations Between Needs Satisfaction In-game and in Life in General.” Psychology of Popular Media 9 (2): 266–278. doi:10.1037/ppm0000227.

- Billieux, J., M. Flayelle, H.-J. Rumpf, and D. J. Stein. 2019. “High Involvement Versus Pathological Involvement in Video Games: A Crucial Distinction for Ensuring the Validity and Utility of Gaming Disorder.” Current Addiction Reports 6 (3): 323–330. doi:10.1007/s40429-019-00259-x.

- Borgogna, N. C., J. Duncan, and R. C. McDermott. 2018. “Is Scrupulosity Behind the Relationship Between Problematic Pornography Viewing and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress?” Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 25 (4): 293–318. doi:10.1080/10720162.2019.1567410.

- Bowditch, L., J. Chapman, and A. Naweed. 2018. “Do Coping Strategies Moderate the Relationship Between Escapism and Negative Gaming Outcomes in World of Warcraft (MMORPG) Players?” Computers in Human Behavior 86: 69–76. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.030.

- Canale, N., C. Marino, M. D. Griffiths, L. Scacchi, M. G. Monaci, and A. Vieno. 2019. “The Association Between Problematic Online Gaming and Perceived Stress: The Moderating Effect of Psychological Resilience.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8 (1): 174–180. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.01.

- Caplan, S., D. Williams, and N. Yee. 2009. “Problematic Internet Use and Psychosocial Well-Being among MMO Players.” Computers in Human Behavior 25 (6): 1312–1319. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.006.

- Casale, S., and G. Fioravanti. 2015. “Satisfying Needs Through Social Networking Sites: A Pathway Towards Problematic Internet Use for Socially Anxious People?” Addictive Behaviors Reports 1: 34–39. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2015.03.008.

- Chang, S.-M., G. M. Y. Hsieh, and S. S. J. Lin. 2018. “The Mediation Effects of Gaming Motives Between Game Involvement and Problematic Internet Use: Escapism, Advancement and Socializing.” Computers & Education 122: 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.007.

- Cohen, S., T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein. 1983. “A Global Measure of Perceived Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 24 (4): 385–396.

- Colder Carras, M., A. J. Van Rooij, D. Van de Mheen, R. Musci, Q.-L. Xue, and T. Mendelson. 2017. “Video Gaming in a Hyperconnected World: A Cross-Sectional Study of Heavy Gaming, Problematic Gaming Symptoms, and Online Socializing in Adolescents.” Computers in Human Behavior 68: 472–479. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.060.

- Consalvo, M. 2009. “There Is No Magic Circle.” Games and Culture 4 (4): 408–417. doi:10.1177/1555412009343575.

- Coyne, S. M., L. A. Stockdale, W. Warburton, D. A. Gentile, C. Yang, and B. M. Merrill. 2020. “Pathological Video Game Symptoms from Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood: A 6-Year Longitudinal Study of Trajectories, Predictors, and Outcomes.” Developmental Psychology 56 (7): 1385–1396. doi:10.1037/dev0000939.

- de Bérail, P., M. Guillon, and C. Bungener. 2019. “The Relations Between YouTube Addiction, Social Anxiety and Parasocial Relationships with YouTubers: A Moderated-Mediation Model Based on a Cognitive-Behavioral Framework.” Computers in Human Behavior 99: 190–204. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.007.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2000. “The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior.” Psychological Inquiry 11 (4): 227–268. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

- Deleuze, J., P. Maurage, A. Schimmenti, F. Nuyens, A. Melzer, and J. Billieux. 2019. “Escaping Reality Through Videogames Is Linked to an Implicit Preference for Virtual Over Real-Life Stimuli.” Journal of Affective Disorders 245: 1024–1031. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.078.

- Di Blasi, M., A. Giardina, C. Giordano, G. L. Coco, C. Tosto, J. Billieux, and A. Schimmenti. 2019. “Problematic Video Game Use as an Emotional Coping Strategy: Evidence from a Sample of MMORPG Gamers.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.02.

- Dienlin, T., P. K. Masur, and S. Trepte. 2017. “Reinforcement or Displacement? The Reciprocity of FtF, IM, and SNS Communication and their Effects on Loneliness and Life Satisfaction.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22 (2): 71–87. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12183.

- Elhai, J. D., J. C. Levine, and B. J. Hall. 2019. “The Relationship Between Anxiety Symptom Severity and Problematic Smartphone Use: A Review of the Literature and Conceptual Frameworks.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 62: 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.11.005.

- Ferguson, C. J. 2009. “Is Psychological Research Really as Good as Medical Research? Effect Size Comparisons Between Psychology and Medicine.” Review of General Psychology 13 (2): 130–136. doi:10.1037/a0015103.

- Festl, R., M. Scharkow, and T. Quandt. 2013. “Problematic Computer Game Use among Adolescents, Younger and Older Adults: Problematic Computer Game Use.” Addiction 108 (3): 592–599. doi:10.1111/add.12016.

- Griffiths, M. D., D. J. Kuss, and D. L. King. 2012. “Video Game Addiction: Past, Present and Future.” Current Psychiatry Reviews 8 (4): 308–318. doi:10.2174/157340012803520414.

- Griffiths, M. D., A. M. Lewis, A. B. O. de Gortari, and D. J. Kuss. 2017. The Use of Online Forum Data in the Study of Gaming Behavior. SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781473994812.

- Griffiths, M. D., T. van Rooij, D. Kardefelt-Winther, V. Starcevic, O. Király, S. Pallesen, K. Müller, M. Dreier, M. Carras, and N. Prause. 2016. “Working Towards an International Consensus on Criteria for Assessing Internet Gaming Disorder: A Critical Commentary on Petry et al. (2014).” Addiction 111 (1), 167–175. doi:10.1111/add.13057.

- Grömping, U. 2006. “Relative Importance for Linear Regression in R: The Package Relaimpo.” Journal of Statistical Software 17 (1): 1–27.

- Gros, L., N. Debue, J. Lete, and C. van de Leemput. 2020. “Video Game Addiction and Emotional States: Possible Confusion Between Pleasure and Happiness?” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2894. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02894.

- Hartmann, T., Y. Jung, and P. Vorderer. 2012. “What Determines Video Game Use?: The Impact of Users’ Habits, Addictive Tendencies, and Intentions to Play.” Journal of Media Psychology 24 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000059.

- Hays, R. D., and M. R. DiMatteo. 1987. “A Short-Form Measure of Loneliness.” Journal of Personality Assessment 51 (1): 69–81.

- Heimberg, R. G., G. P. Mueller, C. S. Holt, D. A. Hope, and M. R. Liebowitz. 1992. “Assessment of Anxiety in Social Interaction and Being Observed by Others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale.” Behavior Therapy 23 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80308-9.

- Henrich, J., S. J. Heine, and A. Norenzayan. 2010. “The Weirdest People in the World?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33 (2–3): 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

- Hilgard, J., C. R. Engelhardt, and B. D. Bartholow. 2013. “Individual Differences in Motives, Preferences, and Pathology in Video Games: The Gaming Attitudes, Motives, and Experiences Scales (GAMES).” Frontiers in Psychology 4. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00608.

- Hou, X.-L., H.-Z. Wang, T.-Q. Hu, D. A. Gentile, J. Gaskin, and J.-L. Wang. 2019. “The Relationship Between Perceived Stress and Problematic Social Networking Site Use among Chinese College Students.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8 (2): 306–317. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.26.

- Howell, R. T., M. Ksendzova, E. Nestingen, C. Yerahian, and R. Iyer. 2017. “Your Personality on a Good Day: How Trait and State Personality Predict Daily Well-Being.” Journal of Research in Personality 69: 250–263. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2016.08.001.

- Iacovides, I., and E. D. Mekler. 2019. “The Role of Gaming During Difficult Life Experiences.” Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ‘19, 1–12. doi:10.1145/3290605.3300453.

- Jo, Y. S., S. Y. Bhang, J. S. Choi, H. K. Lee, S. Y. Lee, and Y.-S. Kweon. 2019. “Clinical Characteristics of Diagnosis for Internet Gaming Disorder: Comparison of DSM-5 IGD and ICD-11 GD Diagnosis.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 8 (7): 945. doi:10.3390/jcm8070945.

- Kaczmarek, L. D., and D. Drążkowski. 2014. “MMORPG Escapism Predicts Decreased Well-Being: Examination of Gaming Time, Game Realism Beliefs, and Online Social Support for Offline Problems.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17 (5): 298–302. doi:10.1089/cyber.2013.0595.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. 2014a. “A Conceptual and Methodological Critique of Internet Addiction Research: Towards a Model of Compensatory Internet use.” Computers in Human Behavior 31: 351–354. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. 2014b. “The Moderating Role of Psychosocial Well-Being on the Relationship Between Escapism and Excessive Online Gaming.” Computers in Human Behavior 38: 68–74. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.020.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. 2014c. Excessive Internet Use – Fascination or Compulsion? Dissertation Thesis at London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. 2015. “A Critical Account of DSM-5 Criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder.” Addiction Research & Theory 23 (2): 93–98. doi:10.3109/16066359.2014.935350.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D., A. Heeren, A. Schimmenti, A. van Rooij, P. Maurage, M. Carras, J. Edman, A. Blaszczynski, Y. Khazaal, and J. Billieux. 2017. “How Can we Conceptualize Behavioural Addiction Without Pathologizing Common Behaviours?: How to Conceptualize Behavioral Addiction.” Addiction 112 (10): 1709–1715. doi:10.1111/add.13763.

- Karsay, K., D. Schmuck, J. Matthes, and A. Stevic. 2019. “Longitudinal Effects of Excessive Smartphone Use on Stress and Loneliness: The Moderating Role of Self-Disclosure.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 22 (11): 706–713. doi:10.1089/cyber.2019.0255.

- Kenny, D. A. 2018. Moderator Variables. http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm.

- Kim, J., R. LaRose, and W. Peng. 2009. “Loneliness as the Cause and the Effect of Problematic Internet Use: The Relationship Between Internet Use and Psychological Well-Being.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 12 (4): 451–455. doi:10.1089/cpb.2008.0327.

- King, D. L., J. Billieux, N. Carragher, and P. H. Delfabbro. 2020. “Face Validity Evaluation of Screening Tools for Gaming Disorder: Scope, Language, and Overpathologizing Issues.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 9 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1556/2006.2020.00001.

- Kneer, J., D. Munko, S. Glock, and G. Bente. 2012. “Defending the Doomed: Implicit Strategies Concerning Protection of First-Person Shooter Games.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 15 (5): 251–256. doi:10.1089/cyber.2011.0583.

- Kneer, J., and D. Rieger. 2015. “Problematic Game Play: The Diagnostic Value of Playing Motives, Passion, and Playing Time in Men.” Behavioral Sciences 5 (2): 203–213. doi:10.3390/bs5020203.

- Kökönyei, G., N. Kocsel, O. Király, M. D. Griffiths, A. Galambos, A. Magi, B. Paksi, and Z. Demetrovics. 2019. “The Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Problem Gaming Among Adolescents: A Nationally Representative Survey Study.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 273. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00273.

- Lafrenière, M.-A. K., R. J. Vallerand, E. G. Donahue, and G. L. Lavigne. 2009. “On The Costs and Benefits of Gaming: The Role of Passion.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 12 (3): 285–290. doi:10.1089/cpb.2008.0234.

- Lalande, D., R. J. Vallerand, M.-A. K. Lafrenière, J. Verner-Filion, F.-A. Laurent, J. Forest, and Y. Paquet. 2017. “Obsessive Passion: A Compensatory Response to Unsatisfied Needs: Passion and Need Satisfaction.” Journal of Personality 85 (2): 163–178. doi:10.1111/jopy.12229.

- LaRose, R. 2010. “The Problem of Media Habits.” Communication Theory 20 (2): 194–222. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01360.x.

- LaRose, R., C. A. Lin, and M. S. Eastin. 2003. “Unregulated Internet Usage: Addiction, Habit, or Deficient Self-Regulation?” Media Psychology 5 (3): 225–253. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1999. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York: Springer Pub. Co.

- Lemmens, J. S., P. M. Valkenburg, and D. A. Gentile. 2015. “The Internet Gaming Disorder Scale.” Psychological Assessment 27 (2): 567–582. doi:10.1037/pas0000062.

- Lemmens, J. S., P. M. Valkenburg, and J. Peter. 2011. “Psychosocial Causes and Consequences of Pathological Gaming.” Computers in Human Behavior 27 (1): 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.015.

- Lindeman, R. H., P. F. Merenda, and R. Z. Gold. 1980. Introduction to Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis. Glenview: Scott, Foresman and Company.

- Männikkö, N., H. Ruotsalainen, J. Miettunen, H. M. Pontes, and M. Kääriäinen. 2020. “Problematic Gaming Behaviour and Health-Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Health Psychology 25 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1177/1359105317740414.

- Maroney, N., B. J. Williams, A. Thomas, J. Skues, and R. Moulding. 2019. “A Stress-Coping Model of Problem Online Video Game Use.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 17 (4): 845–858. doi:10.1007/s11469-018-9887-7.

- Martončik, M., and J. Lokša. 2016. “Do World of Warcraft (MMORPG) Players Experience Less Loneliness and Social Anxiety in Online World (Virtual Environment) Than in Real World (Offline)?” Computers in Human Behavior 56: 127–134. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.035.

- Mattick, R. P., and J. C. Clarke. 1998. “Development and Validation of Measures of Social Phobia Scrutiny Fear and Social Interaction.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 36 (4): 455–470. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6.

- Mehroof, M., and M. D. Griffiths. 2010. “Online Gaming Addiction: The Role of Sensation Seeking, Self-Control, Neuroticism, Aggression, State Anxiety, and Trait Anxiety.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 13 (3): 313–316. doi:10.1089/cyber.2009.0229.

- Perlman, D., and L. A. Peplau. 1981. “Toward a Social Psychology of Loneliness.” In Personal Relationships in Disorder, edited by S. Duck, and R. Gilmour, 31–56. London: Academic Press.

- Perry, R., A. Drachen, A. Kearney, S. Kriglstein, L. E. Nacke, R. Sifa, G. Wallner, and D. Johnson. 2018. “Online-only Friends, Real-Life Friends or Strangers? Differential Associations with Passion and Social Capital in Video Game Play.” Computers in Human Behavior 79: 202–210. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.032.

- Petry, N. M. 2019. Pause and Reset: A Parent’s Guide to Preventing and Overcoming Problems with Gaming. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Przybylski, A. K., A. Orben, and N. Weinstein. 2019. “How Much Is Too Much? Examining the Relationship Between Digital Screen Engagement and Psychosocial Functioning in a Confirmatory Cohort Study.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890856719314376. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.017.

- Przybylski, A. K., and N. Weinstein. 2017. “A Large-Scale Test of the Goldilocks Hypothesis: Quantifying the Relations Between Digital-Screen Use and the Mental Well-Being of Adolescents.” Psychological Science 28 (2): 204–215. doi:10.1177/0956797616678438.

- Przybylski, A. K., and N. Weinstein. 2019. “Investigating the Motivational and Psychosocial Dynamics of Dysregulated Gaming: Evidence from a Pre-registered Cohort Study.” Clinical Psychological Science 7 (6): 1257–1265. doi:10.1177/2167702619859341.

- Przybylski, A. K., N. Weinstein, R. M. Ryan, and C. S. Rigby. 2009. “Having to versus Wanting to Play: Background and Consequences of Harmonious versus Obsessive Engagement in Video Games.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 12 (5): 485–492. doi:10.1089/cpb.2009.0083.

- Rieger, D., L. Frischlich, T. Wulf, G. Bente, and J. Kneer. 2015. “Eating Ghosts: The Underlying Mechanisms of Mood Repair via Interactive and Noninteractive Media.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 4 (2): 138–154. doi:10.1037/ppm0000018.

- Rothmund, T., C. Klimmt, and M. Gollwitzer. 2016. “Low Temporal Stability of Excessive Video Game Use in German Adolescents.” Journal of Media Psychology, 1–13. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000177.

- Ryan, R. M., C. S. Rigby, and A. Przybylski. 2006. “The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach.” Motivation and Emotion 30 (4): 344–360. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8.