Abstract

This study applies an interdisciplinary approach to the study of Ming period courtesans (ji 妓) and their activities, combining the close reading of literature and Ming era visual presentations, with insights drawn from the fields of modern courtship and nonverbal behavioral studies to investigate their strategies of signaling seduction. In the Ming era, courtesans used a series of seduction strategies to achieve their goals in the process of interacting with male clients, dividing the entire courtship process into four phases: attention catching, interacting, and developing intimacy, lovemaking, and post-passion transition back to mundane interaction. This study pays close attention to the first two phases. The strategies of the first stage include posture readiness, prop handling, gestural movements, and vocal manipulation. The strategies of the second stage include conversations and touching. Developing high-level skills in signaling seduction was crucial to success in the career of a Ming courtesan. The specific strategies and the order in which they occurred did not appear to be fixed, but courtesans had to be sensitive and adaptable depending to the personalities and needs of their guests.

Introduction and Literature Review

Courtesans (ji 妓) have always been seen as symbols of sex, lust, and seduction, commonly represented as embodying dangerous pleasure and a threat to social order.Footnote1 In the novels, drama scripts, anecdotes, and other literary works of the Ming dynasty, courtesans were often portrayed as idealized figures, endowed with the cultural aspirations of frustrated literati.Footnote2 Nevertheless, in vernacular literature represented by songbooks, negative images of courtesans abound. They are referred to as having “sweet mouths and cruel hearts” 嘴甜心狠, being “selfish” 自私 and “egoistic” 自私自利, being “good at manipulating people” 善於操縱人心, and so on, indicating that they were not to be trusted. The Ming era songbook of folksong lyrics Gua Zhi’er 掛枝兒 (Hanging Branches), compiled by the renowned literatus Feng Menglong 馮夢龍 (1574–1646), contains some highly evocative satirical lyrics about courtesans’ lifestyles and characters. For example, in the song “Fear of Sneaking Off” complaints about brothel courtesan conduct is given from a man’s perspective:

怕閃

風月中的事兒難猜難解,風月中的人兒個個會弄乖。難道就沒一個真實的在?我被人閃怕了,閃人的再莫來。你若要來時也,(將)閃人的法兒改。

Fear of Sneaking Off

Things in the pleasure quarters are difficult to fathom and solve, everyone who lives there indulging in flattery and showing off their cleverness. Is there a single sincere person? I fear it when people sneak off, for those who slip away, don’t return. If you come, you should not slip away again!Footnote3

Feng Menglong collected the songs in Gua Zhi’er from urban areas,Footnote4 the romantic themes and indelicate language indicating a major preoccupation with brothel culture in particular. Here, as elsewhere, male authors devote much attention to interpreting, or possibly over-interpreting, the minutiae of the courtesans’ behavior. Although their overall critical assessment tends to be negative, they do nevertheless recognize (and sometimes exaggerate) the women’s often highly developed skills of seductive manipulation. This current study delves deeper into the courtesans’ methods for signaling and achieving seduction, drawing together findings from Ming period literature and contemporary behavioral studies, with the aim of advancing a fascinating research field.

Although the seduction techniques explored must surely have been embedded within a wide range of performance types by diverse female performer, I focus particularly on women courtesans as their practices are very well documented and seductive strategies lay at the heart of much of their activity. Meanwhile, there is little evidence of seductive strategies playing a significant role in the lives of Ming elite wives, especially because of the strategies’ close associations with the low-status courtesan profession.Footnote5 I also do not explore the seductive strategies of imperial concubines, as they occupied a different social status and their seduction practices are not well documented.Footnote6

Speaking of the sociocultural background in which the courtesans lived, the middle and late Ming dynasty was a period that witnessed a flourishing economy and the emergence of new ideological trends. The economic growth stimulated the developments of commerce, manufacturing, and a population aggregation in cites, which then fueled a culture of lavish consumption among urban dwellers.Footnote7 The pursuit and enjoyment of luxury and entertainment in urban life provided a nearly perfect soil for courtesan culture, prompting it to reach the peak of prosperity.Footnote8

The deeper reasons for the change of Ming era people’s attitudes towards art, cultural life, and sex lie in the birth of commodity economy capitalism, the rise of a civic class, and changes in people’s aesthetic value orientation. In the middle and late Ming dynasties, along with the popularity of Wang Yangming’s 王陽明 advocation of Philosophy of Mind 心學, the literati represented by Li Zhi 李贄 (1527–1602), Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616), and Feng Menglong began to proclaim the importance of qing 情 (emotion, feeling) and zhen 真 (genuineness, authenticity) in ideological and aesthetic circles; the literati class gradually revealed their pursuit of individual liberation and self-worth.Footnote9 The concept of “qing as priority” emphasizes and values secular emotions, claiming the “true feelings between men and women” is the cornerstone of almost all social relations.Footnote10 Such canonization of “true feeling” 真情 made some literati abandon the old conventions of classical literature that originally occupied the mainstream, and instead positively cultivate popular literature and art rooted in civic culture, represented by novels, drama, and vernacular folk songs, for they were considered more emotionally authentic.Footnote11 A typical example is Feng Menglong’s praise and active promotion of erotic folk songs that were widely popular in pleasure venues (represented by songbooks Gua Zhi’er and Shan’ge).Footnote12 Moreover, the Ming literary scholar Zhu Yuanliang 朱元亮 collected over 500 poems and verses from around 180 courtesans from the Jin dynasty to the Ming period and compiled them into Qinglou Yunyu 青樓韻語 (Amorous Words in the Green House). He affirmed the human yearning for love and desire and considered the demand for affective feelings between clients and courtesans to be equal in the entertainment arena:

男女雖異,愛欲則同。 … 客與妓,非居室之男女也。而情則同,女以色勝,男以俊俏伶俐勝,自相貪慕。

Although men and women are different, they share the same love and desire … The clients and the courtesans, they are not husbands and wives living together. Yet their affective emotions are the same, [only] the women prevail in their beauty, and the men in their handsomeness and wit, and they lust after each other.Footnote13

Ming courtesans enjoyed unprecedented high social status and reputation, partly due to their strong connections with the gentry-literati class. This argument has been repeatedly presented by many scholars, including Van Gulik and Hsu Pi-Ching.Footnote14 In sharp contrast to the prosperity of the Ming was the negative attitude towards courtesans in the Qing dynasty. They were becoming increasingly marginalized in Qing elite society due to the revival of classicism, being replaced by the culture of guixiu 閨秀—literature and art created by women from elite families.Footnote15 Courtesans’ positive images dwindled in written records after the early eighteenth century (early Qing), after which they were more often associated with gloomy and negative images.Footnote16

However, the courtesans’ special status puts them on the fringes of society’s traditional family unit. Dorothy Ko asserts that the status of Ming courtesans was fluid, enabling them to permeate domestic realms, becoming concubines through marriage, or private performers.Footnote17 Such permeability into private spheres was not unique to Ming female performers. Beverly Bossler claims that as early as the Southern Song dynasty, the fashion of raising household courtesans with various skills had been popular in literati society.Footnote18

A qualified Ming courtesan should have a beautiful appearance, talent, and aesthetic tastes in line with the literati scholars’ values, as Dorothy Ko and Tseng Yuho have argued.Footnote19 It was essential to present a seductive manner sufficient to attract clients. Some Ming period literati believed that seductive looks or manners, which they called mei 媚, could greatly enhance a woman’s beauty. The renowned aesthetician Li Yu 李漁 expounded in detail on the qualities a perfect woman should possess, in his treatise Xian Qing Ou Ji 閑情偶寄 (Sketches of Idle Pleasures). Although beautiful appearance took precedence over “seductiveness” 媚態, Li Yu fully affirmed the importance of seductiveness in feminine beauty:

媚態之在人身,猶火之有焰,燈之有光,珠貝金銀之有寶色,是無形之物,非有形之物也。

To human beings, seductiveness is like the flame is to the fire, light is to the lamp, and shine is to jewellery. These are invisible, not tangible things.

… …

今之女子,每有狀貌姿容一無可取,而能令人思之不倦,甚至舍命相從者,皆「態」之一字之為崇也。

Considering today’s women, if there is a person today who has no redeeming feature in appearance or physique, but she can make someone long for her tirelessly, even risking his life to follow her, it is because of her “seductiveness” that she is praised.Footnote20

The extent of Li Yu’s interest in feminine aesthetics is reflected in his attention to detail when describing women’s behavioral codes and the musical training they received. For example, he expressed insights about the types of instrument women should study. He believed that playing the xiao (vertical flute) would emphasize a woman’s charms, making her “jade bamboo-like fingers seem more and more slender 玉筍為之愈尖” and her “vermilion lips become smaller 朱唇因而越小.”Footnote21 In addition, Li pointed out that singing and dancing could make a woman’s voice mellow and her body lighter, further adding to her charms, “casually speaking, sounding like the callings of swallows and warblers 隨口發聲,皆有燕語鶯啼之致,” “the way she turns around and walks can make willow twigs wiggle and flowers bloom 回身舉步,悉帶柳翻花笑之容.”Footnote22

Although it initially seems to contradict his assertions about the enhancement of charms through training, Li Yu stated that “attitudes are innate, and cannot be obtained by force 態自天生,非可強造.” Presumably, here, “attitudes” is referring to something more deeply rooted within an individual’s personality. Another Ming writer with similar views was Wanyuzi 宛瑜子, who elaborated his interpretation of mei in the preface of Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 (Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area). He considered natural seductiveness to be the optimal topping for a courtesan:

媚亦有辨焉:塗脂抹粉,妝點顏色,媚之下也。嬌歌嫩舞,誇詡伎倆,媚之中也。天然色韻,亦不脂粉,亦不伎倆,而自令人淫,媚而上矣。

Mei can also be differentiated: applying makeup and coloring one’s appearance is the inferior kind of mei. Sweet singing and dainty dancing, showing off tricks, is the moderate kind of mei. A natural face with charm, without makeup or tricks, yet spontaneously arousing one’s desire, is first-class mei.Footnote23

Let us consider academic explorations of the nature of seductiveness. Although extensive research has been carried out on human nonverbal courtship behavior,Footnote24 very little research has been focused on courtesans’ seductive signaling. There is, however, a small body of seduction scholarship focusing on modern performers. For example, Bart Barendregt investigates the changing art of seduction with a specific focus on Japanese geisha and Thai transgender performers. He argues that in many Asian cultures the courtesan is a promoter of the higher arts.Footnote25 Judith Hanna systematically unpacks the strategies of seduction adopted by American female exotic dancers, some of which bear a striking resemblance to those employed by Ming courtesans, such as grooming, movement, joking, and sensory stimulation (touch, scent, and music).Footnote26 Frank Kouwenhoven and James Kippen’s book compiles a collection of articles exploring the seductive elements operating in a variety of cultural contexts. They argue that certain features can transcend cultural boundaries, such as the alluring qualities of the human voice and witty musical dialogue, both of which were highly valued in connection with the Ming courtesans when signaling seduction.Footnote27 I aim to expand the small body of performance-focused seduction studies by examining pre-modern historical practices—specifically, those of the Ming courtesans.

The two most widely used research methods for exploring human courtship behavior—namely, keen observation of current real-time processes and detailed self-report from subjectsFootnote28—are not viable in this, or any other, historical context. Yet Ming period courtesans and details of their practices are by no means inaccessible. The main approach of this study is a literary analysis of the representation of Ming courtesans’ seduction strategies from various literary genres. By careful and critical analysis of Ming literary textual resources, including novels, lyric poetry collections, and literati notes, it is possible to identify the various seductive practices that they typically employed and which were essential defining features of their profession. Contemporaneous historical art sources, such as paintings and woodblock illustrations combining textual sources with visual art works, afford the opportunity to reconstruct how authors and readers wished to conceive of the interactions with courtesans.

Certainly, there are differences between representation and reality, as we are dealing with artistic representation and must remain honorably agnostic about what really occurred in brothels and bedchambers. The line between the idealized, fanciful depictions of the courtesans by the literati and the reality of the courtesans’ arts and life is not always clear. The problem—familiar to historians of sexuality—is that pre-modern sources usually disclose less about sexual behavior than they do about the representation of sexual behavior. Nevertheless, although representation and reality are not identical, there must be overlap between the real history and the history in written accounts. Courtesans had an interest in living up to cultural ideals, after all, and the literati’s accounts must surely be closely based on reality, even if they offered a somewhat partial and selective vision of lived experience.

Some Essential Definitions: “Seduction” and “Courtship”

Deriving from the French word “séduction,” the English word “seduce” first appears in the late fifteenth century, meaning “to persuade [someone] to abandon their duty.” The original root of these words is the Latin verb “seducere,” where “se-” means “away” and “ducere” means “to lead.” Further definitions include “to entice [someone] into sexual activity,” “to entice [someone] to do or believe something inadvisable or foolhardy,” and “to attract powerfully.”Footnote29 The Chinese equivalent of “seduction” is you 誘, meaning “to instruct, to guide, to lure, to seduce.”Footnote30 Related usages abound in ancient Chinese literature, including: “you, refers to luring or guiding 誘,引也,”Footnote31 “the master skillfully you [instructs] me step by step 夫子循循然善誘人,”Footnote32 “do not be you [seduced] by power and influence 無誘於勢利.”Footnote33 Judith Hanna expertly conflates the ideas about seduction in her study of American adult nude dance, where she succinctly pinpoints some key seductive strategies: “alluring, bewitching, tantalizing, beguiling, inveigling [winning over by coaxing], flattering and exploiting”Footnote34—unsurprisingly, much the same strategies encountered in Ming period descriptions of courtesan practices.

Meanwhile, “courtship” is variously defined as “a period during which a couple develop a romantic relationship before getting married,” “behavior designed to persuade someone to marry or develop a romantic relationship,” “the behavior of animals aimed at attracting a mate,” and “the action of attempting to win a person’s favor or support.”Footnote35 Ultimately, as David Givens argues, courtship involves “encircling” someone or bringing them into a central position in one’s world—the meaning of the ancient Indo-European root “gher-.”Footnote36 Courtship in the Chinese context is referred to as qiu’ai 求愛, although the term was not widely used until modern times. However, courtship-related concepts have long existed. One of the most famous historical examples is the song feng qiu huang 鳳求凰 (a male phoenix courting a female phoenix) composed by Sima Xiangru 司馬相如 (c. 179–117 bc), a Han dynasty literatus, when he was courting Zhuo Wenjun 卓文君.Footnote37 In human cultures, intimate sexual contact is achieved through courtship, a negotiation based on nonverbal signals and verbal communication.Footnote38 Of course, as Bath L. Bailey details in her study of twentieth-century courtship practices in America, the strategies that men and women apply in their pursuits of intimacy are often not geared towards marriage. Indeed, the psychosocial objectives tend to be complex and varied, and most courtship behavior does not reach the intimate stage, let alone marriage.Footnote39

In the world of the Ming period pleasure quarters, the courtesans did not generally engage in courtship practices and call upon seductive strategies for the purposes of securing marriage. Rather, courtship and seduction were routinized as defining features of their profession—in other words, primary means for serving their clients and achieving higher returns (money, connections, reputation, and more). Here, then, I propose that courtesans’ courtship was geared towards winning favor for personal benefit. In addition, I argue that in the courtesan-guest relationship, the courtesan tended to take a more active role of self-presentation (in subtle or bold ways, emitting verbal or nonverbal signals) in comparison with courtship patterns in other dominions. In the courtesan’s realm, she was the performer, the seducer, and action-taker, while the male guest would often become the viewer, the object of seduction, and the action-follower.

Courtship Process in the Pleasure Quarters: Four Phases

Researchers of human courtship identify courtship behavior to be sequentially ordered across multiple stages. Psychiatrist Albert Scheflen, for example, famously examined courtship messaging between therapists and clients, identifying the following behaviors, spread across four stages: displaying courtship readiness (such as tensing muscles and straightening torso); preening (stroking hair, glancing in the mirror, neatening clothing); presenting positional cues (leaning forward, adopting more intimate conversational mode); and giving cues of invitation (flirtatious eye movements, displaying palms, rolling the hip).Footnote40 Scheflen influentially argued that many, but not all, of these behaviors would surely be universals of courtship behavior. Subsequently, Ray Birdwhistell portrayed more than twenty steps from initial male and female interaction to the completion of an intimate sexual relationship,Footnote41 while Desmond Morris narrowed the sequence down to twelve steps (though fast couples could skip certain stages).Footnote42 Around ten years later, Joan Lockard and Robert Adams observed a large number of couples and classified their courting behaviors according to different ages and genders, identifying numerous key signals such as kissing, handholding, hugging, self-grooming, eye contact, smiling, laughing, touching, and playing.Footnote43 Meanwhile, by applying self-report research methods (such as surveys and interviews), Clinton Jesser and others have further confirmed just how important nonverbal signaling is in courtship behavior,Footnote44 with women tending to use indirect nonverbal signaling strategies more extensively than men in most contexts.Footnote45 Subsequent scholarship in this field has both confirmed and built upon the pioneering work outlined above, with, for example, David Buss presenting an especially detailed exploration into seduction strategies and, crucially, highlighting the prevalence of conflict, competition and manipulation in the realm of courtship—these being recurrent themes in the Ming period accounts also.Footnote46

As suggested above, the field of courtship studies has centered on modern courtship patterns in the West, and it is evident that a large portion of the observations do not map directly onto Ming period courtship practices. Different research objects and cultural contexts need to be treated differently, being sensitive to cultural specificity. Comparing modern courtship behaviors with the interaction between courtesans and guests in the Ming era brothel context, although some of the behaviors are shared (such as quick glances or coy giggles),Footnote47 others are less likely to occur in the early stages of a Ming era courtship context (such as kissing, touching thighs, and other behaviors). Therefore, it is necessary to consider the courtesans’ practices on their own terms, drawing from the evidence while being wary of overly speculative reasoning.

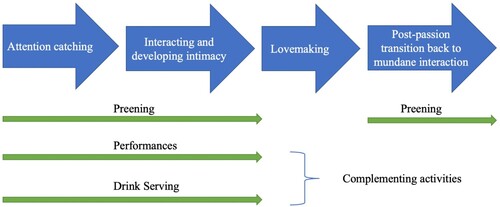

Based on my analysis of Ming period descriptions, I divide the courtesans’ courtship process into four phases: attention catching, interacting and developing intimacy, lovemaking, and post-passion transition back to mundane interaction (see ). This article focuses especially on the first two phases.

Certain courtship-related behaviors evidently occur throughout much of this four-part process: for example, preening runs through all phases except phase three (lovemaking) and individuals would typically also indulge in performance, drink serving, and other complementary activities to help advance the courtship proceedings (mainly in the first two phases). It is hard to determine to what extent there would have been clear boundaries between these phases, though I deem, based on the forementioned courtship studies, overlap would have been typical.

My four-part schema draws influence from several key theorists’ classifications of courtship behavior, including Scheflen’s forementioned four-part model, Morris’s study of universal intimate behavior, Lockard and Adams’ analysis of public courtship behavior, and Buss’s extended study. Unfortunately, the surviving Ming period literary works do not provide sufficiently detailed, systematic evidence to construct a more expansive multi-part schema. However, I maintain that many of them offer accurate (though partial) representations. After all, there is ample evidence that the literati were frequenters of brothels, with extensive first-hand experience of the courtesans’ practices. For instance, many pieces in Feng Menglong’s song-books Shan’ge and Gua Zhi’er uncover Ming era courtesans’ daily lives and affective states.Footnote48 The famous Ming period novel Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅 (The Plum in the Golden Vase) depicts a large number of brothel and courtesan related scenes, some taking place in entertainment venues and others in private household parties.Footnote49 Written by Wan Yuzi 宛瑜子 during the Wanli Period (1573–1620), Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 is a book about courtesan-ranking in the Suzhou area, with a wealth of poems, lyrics, and comments made on them.Footnote50

preening, musical performance, and drinking

Before examining each courtship phase in succession, it is necessary to explore the elements that recurred frequently throughout much of the proceedings: preening, musical performance (singing, dancing and playing instruments), and drinking.

Preening is a conspicuous feature at any stage but is most common in the preparation stage. Scheflen states that preening tends to be an endeavor to perfect one’s appearance.Footnote51 Common manifestations include grooming one’s hair, retouching makeup, and rearranging clothes.Footnote52 Not surprisingly, Ming era literary works are packed full of references to preening, usually including richly detailed descriptions that show the gorgeousness of the ideal courtesans’ clothing and accessories, and indicate the extensive time and effort they devoted to their physical appearance. A lavish example of this is presented in Jin Ping Mei, when the courtesan Li Guijie is being described:

於是向月娘鏡臺前,重新妝照打扮出來。眾人看見他頭戴銀絲䯼髻,周圍金累絲釵梳,珠翠堆滿。上著藕絲衣裳,下著翠綾裙。尖尖趫趫一對紅鴛。粉面貼著三個翠面花兒,一陣異香噴鼻。

Thereupon, she availed herself of Yue-niang’s mirror stand to retouch her makeup and adjust her attire and then went out to the reception hall.

When the company looked up, they saw that on her head she wore:

A chignon enclosed in a fret of silver filigree,

fastened in place all round with:

Gold filigree pins and combs,

on which:

Pearls and trinkets rose in piles.

Above, she wore:

A blouse of pale lavender silk;

below, she wore:

A skirt of turquoise satin,

revealing:

The upturned points of her tiny golden lotuses,

Decorated with a pair of red phoenixes.

On her painted face she wore:

Three turquoise beauty patches;

From her body:

A gust of exotic fragrance assailed the nostrils.Footnote53

The first sentence of this passage points out that Guijie engaged in a series of typical preening behaviors before appearing in public: checking her appearance in the mirror, touching up her makeup and rearranging her clothing. A series of detailed descriptions of elaborate clothing and accessories then further suggest that Guijie had dressed herself elaborately and meticulously before her reveal: the silver, gold, and pearl-encrusted hair jewelry and silk blouse were the embodiment of luxury; the delicate makeup on her face; the red phoenixes adorning her tiny golden lotus-like feet, and the exotic aroma; all were elements of seduction.

Preening is also often a symbolic performative act, intended to be viewed by others.Footnote54 The next example—a song text from Jin Ping Mei—demonstrates how this kind of preening would occur in the later stages of courtship also. In this case, the penultimate sentence indicates that the two protagonists spent the previous night together. Here, the woman coyly adjusts her delicate hair accessories to evoke particular effects in her lover who is watching on:

轉過雕闌正見他,斜倚定荼䕷架。佯羞整鳳釵,不說昨宵話。笑吟吟,捏將花片兒打。

Skirting the carved balustrade, he catches sight of her,

Leaning against the rose-leaved raspberry trellis.

Coyly adjusting her phoenix hairpin,

She says nothing of last night’s events,

But, smiling ingratiatingly,

Plucks a blossom and tosses it at him.Footnote55

In addition to the act of preening, musical performances and drinking also appear to have occurred throughout much of the courtship process, providing complementary sensory stimuli to evoke a conducive mood. is a Ming era visual presentation illustrating the strong link between alcohol consumption and courtesanship activities.

Fig. 2. 豪飲圖 Changyin Tu, “An Illustration of Cheerful Drinking.”Footnote116 The text in the picture indicates that this is “Number one in the First class, Feng Wu-ai 馮無埃.”Footnote117 Situated on the left, the courtesan is smiling as she watches the man sitting opposite, with drinking cups in front of them. This is an outdoor setting, judging by the trees and the mountains behind.

Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.

![Fig. 2. 豪飲圖 Changyin Tu, “An Illustration of Cheerful Drinking.”Footnote116 The text in the picture indicates that this is “Number one in the First class, Feng Wu-ai 馮無埃.”Footnote117 Situated on the left, the courtesan is smiling as she watches the man sitting opposite, with drinking cups in front of them. This is an outdoor setting, judging by the trees and the mountains behind.Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.](/cms/asset/96742776-1962-4aa1-bfac-676201bcdda6/ymng_a_2249327_f0002_oc.jpg)

Drinking and musical performance tend to occur together as near-essential components of the brothel experience. A wide variety of musical forms are recorded as having been performed in brothels, including ensemble music-making, singing with instrumental accompaniment, and unaccompanied singing (or sometimes with just a beat provided, for example by a fan or clappers). The music performed by Ming era courtesans can be broadly divided into opera extracts (from traditions like chuanqi opera 傳奇 and kunqu opera 崑曲, widely praised by Ming literati) and stand-alone songs (including sanqu 散曲, with styles and lyrics considered especially artistic, and more rustic, popular xiaoqu 小曲, which originated in the countryside and later became popular in brothel contexts).Footnote56 The contexts for a typical courtesan performance could be noisy drinking parties, banquets, or various gatherings, or tranquil and confidential private residences.Footnote57 Much importance was attached to vocal expression over instrumental display, in line with the literati circle’s conviction in the aesthetic superiority of vocal melody. As a result, the northern style of performance (emphasizing stringed instrumental accompaniment and adapting a heroic, rough singing style),Footnote58 which was popular in the first half of the Ming dynasty, was gradually replaced by the southern style (focusing on subtle vocal melodic artistry, with light instrumental accompaniment).Footnote59

In many cases, music performance was interspersed amongst other activities, such as game playing, drinking, and conversation, playing a major role in stimulating an alluring atmosphere, strengthening a sense of continuity, and engaging the clients’ full attentions—distracting them away from other mundane concerns.

The following two examples demonstrate the typical pairing of music and drink in the courtship context. The first is taken from the late Ming era man of letter Yu Huai’s 余懷memoirs of courtesan culture in Qinhuai region, Banqiao Zaji 板橋雜記 (Miscellaneous Records of the Plank Bridge). The scene depicts the ample employment of musical performance in banquets hosted by the courtesan Li Da’niang:

李大娘 … … 置酒高會,則合彈琶琶、箏,或狎客沈雲、張卯、張奎數輩,吹洞簫、笙管,唱時曲。酒半,打十番鼓。

During grand feasts and gatherings, they played the pipa and the zither in unison, and sometimes intimates [Da’niang’s frequenters] such as Shen Yun, Zhao Mao, and Zhang Kui played the flute and the sheng pipes and sang popular songs. When they had had enough wine, they would play the ten-variation ensemble.Footnote60 [Li Wai-yee translation]

The second example is a Ming era popular song that vividly describes what a late-night brothel guest would be treated to—wine, games, and songs:

夜客

站階頭一更多,姻緣天湊。叫一聲有客來,點燈(來)上樓。夜深東道須將就,擺個寡榼子,猜拳豁指頭。唱一只《打棗竿兒》也,(客官)再請一杯酒。

Night Guest

Standing on the stairs from seven to nine at night, waiting, my marriage is pieced together by Heaven. Shouting out that the guest is here, I light the lamp [and] go upstairs. At midnight, please bear with your host, setting out the bland wine and playing a finger-guessing game. Singing the tune Beating the Jujube Branches, [my guest,] please have another glass of wine.Footnote61

The following example demonstrates that musical performance could sometimes continue throughout the courtship process, right up to the intimacy stage. Here, the courtesan Sister Mei provides a variety of performances (instrument playing, singing, and dancing) to her favorite guest, Qin Zhong, until he is deeply affected, and they go to bed together:

是夜,美娘吹彈歌舞,曲盡生平之技,奉承秦重。秦重如做了一個遊仙好夢,喜得魄蕩魂消,手舞足蹈。夜深酒闌,二人相挽就寢。

That evening, Sister Mei played her musical instruments, sang, and danced, trying to please him to the best of her ability. Qin Zhong was thrown into raptures and almost danced for joy, feeling as if he were in a dream, roaming the fairyland. When night came and the wine was finished, the two of them went to bed in each other’s arms.Footnote62 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

Having now introduced these three central elements that ran through much of the courtship experience—preening, musical performance, and drinking—discussion will presently turn to explore the four phases of courtship in succession.

phase 1: attention catching

In line with the observations of behavioral studies researchers, descriptions of the courtesans’ initial courtship behaviors often include references to seduction signals such as posture readiness display, prop manipulation, interest-showing gesture, and shift in vocal register.

Scheflen details some key physical changes that typically characterize the initial stage of courtship, including high muscle tension, brighter eyes, and a change in skin tone from blush to pale.Footnote63 Not surprisingly, Ming period descriptions of early-phase courtship also highlight these kinds of transformation, for example:

建封與樂天俱喜調韻清雅,視其精神舉止,但見:花生丹臉,水剪雙眸,意態天然,迥出倫輩。回視其餘諸妓,粉黛如土。

Charmed by the sweet music, Zhang Jianfeng and Bai Juyi took a good look at the player and saw that, with rosy cheeks and bright, sparkling eyes, she had a far more refined and natural air than her peers. Turning their eyes to the other courtesans, Jianfeng and Juyi found them all as unworthy as dirt.Footnote64 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

Posture readiness

In animal courtship, Gersick and Kurzban suggest males typically display their most admirable qualities openly, broadcasting their signals as widely as possible with intentions of securing the best mate.Footnote65 In contrast, flirting, which is believed to be a behavior exclusively for humans and primates, varies greatly in its manifestations, ranging from overt postures and behaviors to much more subtle, ambiguous, or even covert actions, the latter serving to minimize undesirable social costs.Footnote66

One of the postural strategies that Ming period courtesans often conducted was “leaning against the door”—positioning themselves at the threshold between the street and the brothel and deliberately displaying their charms. One example of this comes from a short story about a monk, Liu Cui, who is reincarnated as a prostitute. Here, Liu mimics the behaviors of the neighborhood courtesans, using overt seductive strategies to lure the “ogling men” to her door:

這柳翠每日清閑自在,學不出好樣兒,見鄰妓家有孤老來往,他心中歡喜,也去門首賣俏,引惹子弟們來觀看。眉來眼去,漸漸來家宿歇。

In her idleness, Liu Cui watched clients of the brothels come and go in the neighborhood and, merrily following the examples set by prostitutes all around her, also took to parading her charms at her door. Ogling men soon began to follow her into the house and stay overnight.Footnote67 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

One encounters a similar example in the lyrics for the song “Standing at the Door,” included in the song collection Gua Zhi’er. This song again refers to the standard practice of standing at the threshold to solicit clients, as performed by Ming courtesans and prostitutes:

站門

… … 管你倚破守門兒磨穿了壁,管你站酸了腳兒悶肭了腰。眼盼盼巴不能勾俏麗的郎君也,來了,啐!又向別人家進去了。

Standing at the Door

Who cares if you lean against the door till it breaks, against the wall till it wears through? Who cares if your feet stand till they’re sore and your waist grows fat? Hoping to seduce a pretty gentleman, yet when he comes, bah! He goes into another house.Footnote68

Yet sometimes a demure posture is more alluring than intentionally flirting. In the short story “Shan Fulang’s Happy Marriage in Quanzhou,” what courtesan Yang Yu is doing is conspicuously not flirting, but rather showing her demureness, and drawing attention and setting herself apart from her peers by doing so:

只是一件,他終是宦家出身,舉止端詳。每詣公庭侍宴,呈藝畢,諸妓調笑謔浪,無所不至;楊玉嘿然獨立,不妄言笑,有良人風度。為這個上,前後官府,莫不愛之重之。

One thing that distinguished her [courtesan Yang Yu] from the rest of the girls was that, being from a genteel official’s family, she was demure and well-mannered. After performing at feasts in a yamen, all the other girls always flirted wantonly with the men, stopping at nothing, while she alone stood by herself in silence, never speaking or laughing improperly, more like a well-bred woman than a courtesan. For this, she won much admiration and respect from all and sundry.Footnote69 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

This passage indicates that Yang Yu’s good family background played a part in the cultivation of her talents and, earlier in the story, it is mentioned that she “was quite literate and was especially skilled in the art of conversation,”Footnote70 had learned classics and poetry from childhood, and had been taught singing and dancing by the madam of the brothel. These experiences had contributed to her elegant temperament. It is no surprise that many Ming literati preferred the conduct of better educated courtesans over that of “wanton” singing girls, presumably appreciating opportunities to share knowledge, ideas and values, and thereby experiencing a deeper interpersonal connection.

As the above examples amply illustrate, courtesans would employ a wide range of accessories and textiles to create a suitably alluring affect—and at this point it seems necessary to acknowledge the often-discussed practice of foot-binding小腳. References to bound feet—commonly alluded to as “golden lotus” 金蓮—are abundant in the Ming period literature and, although the binding caused misshapenness and pain, it is apparent that the tiny feet were, nevertheless, widely regarded as beautiful. As Dorothy Ko insightfully points out, while serving to conceal and thereby evoke fascination, the binding also transformed the bare feet into an additional decorative focus for the viewer.Footnote71 Accordingly, the Ming period writers often allude to bound feet alongside the other alluring adornments worn by charming, sexually appealing female characters, although explicit descriptions are more common in sex scenes. In the following two examples, the male authors home in on the most alluring attributes of some household courtesans, similarly alluding to the way in which the women’s feet are only just visible under the concealment of skirts or trouser ends, stimulating imagination and fantasy:

香袋兒身邊低掛,抹胸兒重重紐扣,褲腳兒臟頭垂下。往下看,尖趫趫金蓮小腳,雲頭巧緝山牙老鴉。

A sachet of pomander hangs low

at her waist.

The rows of frogs on her bodice

are neatly fastened;

Her ankle leggings, concealed above,

extend below.

The upturned points of her tiny golden lotuses

are just visible;

With a pattern of mountain peaks embroidered

on the tips of their toes.Footnote72 [David Roy translation]

… …

富新舉目一看,好一雙標致的艷婢,都是桃紅紗衫 … … 戴著茉莉花,金簪珠墜,下邊微露尖尖小腳,穿著白紗褶褲,大紅平底花鞋,不覺那魂靈兒竟鉆到他兩人身上去了。

Fu Xin looked up and saw a pair of gorgeous servant-girls, both were dressed in peach gauze clothes … … They wore jasmine flowers, gold hairpins and pearl pendants, the pointy feet peeped slightly under the white gauze trousers with pleats, bright red flat shoes embroidered with flowers. Unconsciously, his soul was enchanted by these two beautiful women.Footnote73

Use of props

Courtesans often employed props during the first phase of courtship, either to highlight or obscure their attractive attributes—the hiding of features communicating an attractive coyness. In certain contexts, courtesans would commonly employ fans, sleeves, or other props to cover their faces when meeting guests for the first time, creating a tantalizing effect while, at the same, demonstrating conventional modesty on meeting a member of the opposite sex. For instance, in the short story “Secretary Qian Leaves Poems on the Swallow Tower,” the courtesan Guan Panpan answers a guest’s questions with sleeves shielding her face, not necessarily because this is her first meeting with the guests and she is shy but possibly because she is already endeavoring to secure and develop their interests:

盼盼據卸胡琴,掩袂而言 … …

Guan Panpan put down the pipa and said, shielding her face with her sleeves … … Footnote74 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

Ming era courtesans often employed fans, with the round-shaped variety being used exclusively by women because of its face-covering function, while the folding type was mainly used by men of letters.Footnote75 In addition to their obvious practical use, fans were often used as decoration to augment female attractiveness. Huang E 黃峨 (1498–1569), a Ming poetess, once wrote a poem “The Song of Picking Tea” 采茶歌, describing a scene of a group of beauties wandering in a garden. In this poem, one of the verses mention the actions of folding sleeves and waving fans:

一個弄青梅攀折短墻梢,一個蹴起秋千出林杪,一個折回羅袖把做扇兒搖。

One pulled down and broke a green plum twig on the wall and played with it, one kicked up the swing until it was higher than the trees, one folded her silken sleeves and waved her fan.Footnote76

Fans could also be used by Ming dynasty courtesans to cover faces and convey charm in a subtle way. This ingenious use of the fan is adopted in the entrance scenes of the two courtesan-performers in Jin Ping Mei, and the descriptions are alike:

(李桂姐)就用灑金扇兒掩面,佯羞整翠,立在西門慶面前。

[The female singer Li Guijie] hiding her face behind her gold-flecked fan,

While coyly adjusting her hair ornaments,

she took her stand in front of Hsi-men Ch'ing.

… …

(鄭愛月)就因灑金扇兒掩著粉臉,坐在旁邊。

[The courtesan Zheng Aiyue] concealed her powdered face behind a gold-flecked fan and sat down next to him.Footnote77 [David Roy translation]

Movement

Unsurprisingly, courtesans typically attributed great care and attention to cultivating elegant and attractive ways of moving, considering every part of their body and also the associated movements of fabrics and accessories. For example, in preparation for pouring wine, a courtesan might first seductively preen her hair, then move elegantly closer to the client, lift her arm in such a way that the sleeves sway and tantalizingly briefly reveal a delicate forearm, and then smoothly tilt her delicate wrist to pour the liquid into his cup. In such a way, simple actions would serve to highlight multiple body parts. In Ming period literature, one encounters references to slender waists with particular frequency, and this is perhaps not surprising given that female waist-hip ratio (slim waist and large hip) is a highly salient indicator of human physical and sexual attractiveness across cultures, suggestive of youth, good health, and fertility.Footnote78 In ancient China, the literati’s preference for a slim waist was rigid, almost cruel: it should be as thin and soft as a willow twig to match their aesthetic ideals. Accordingly, Jin Ping Mei includes a wealth of descriptions praising slender waists: “瘦腰肢一撚堪描 the handful of her slender waist deserved a painting”;Footnote79 “裊娜宮腰迎出塵 displaying slender and lithesome waists, they are out of this world”;Footnote80 “嫩腰兒似弄風楊柳 her lissome waist reminds one of willow fronds tossed in the wind.”Footnote81

Meanwhile, the details of a courtesan’s hands would enter the foreground when she played an instrument, so references to beautiful slender fingers abound in descriptions of musical performance. In Jin Ping Mei, for example, at one point, we read of a courtesan who “輕舒玉指,款跨鮫綃 deftly extended her jade fingers [and] gently strummed the silken strings”Footnote82—jade, of course, being especially highly prized as a rare, delicate material. Another similar example, also from Jin Ping Mei, reads as follows:

當下桂姐輕舒玉指,頃撥冰弦,唱了一回。

Thereupon, Li Kuei-chieh:

Deftly extended her slender fingers,

Impulsively plucked the icy strings,

and proceeded to sing for a while.Footnote83 [David Roy translation]

Visual representations also attest to this penchant for elegant slender fingers. , for example, shows a courtesan playing the pipa four-stringed lute with her slender, pale fingers gracefully positioned close to the strings, while her sleeves collect in elegant folds to reveal her slender left forearm.

Fig. 3. A female entertainer plays the pipa. Her delicate, shapely fingers are an alluring point of focus as she displays her musical skills.Footnote118

Source: “Ximen Foolishly Presents His New Wife, Mistress Ping, to His Worthless and Bibulous Guests 傻幫閑趨奉鬧華筵(金瓶梅插畫冊).” The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, eighteenth century. Album leaf, ink and color on silk.

The alluring movement of fabric—particularly sleeves—appears to have been extensively employed as a seductive tactic, since it frequently appears in literary accounts even before the Ming dynasty. To cite an example, the following poem by Song-era literatus Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101) describes a beautiful courtesan who was skilled at singing and dancing, emphasizing the enchanting movements of her sleeves in the first sentence:

舞袖蹁躚,影搖千尺龍蛇動。歌喉宛轉,聲撼半天風雨寒。

Her dancing sleeves twist and waver; her shadow moves a thousand feet, like a dragon or snake writhing. A warbling song from her throat, the sounds shaking half of heaven and chilling wind and rain.Footnote84

吐微音以按節,翥修袖以雙迎。

[She] emitted faint sounds, providing a rhythm for her dance,

flinging her long slender sleeves high into the air.Footnote86

一面輕搖羅袖,款跨鮫綃,頓開喉音,把弦兒放得低低的,彈了個四不應山坡羊。

[She] Lightly flaunted her silken sleeves,

Gently strummed the silken strings, and:

Commencing to sing in full voice,

with her instrument tuned to a low pitch, performed a song to a medley version of the tune “Sheep on the Mountain Slope.”Footnote87 [David Roy translation]

In addition to the movement of sleeves, other kinds of fabric movement are also commonly referenced in Ming period descriptions of courtesans. For instance, there is the movement of a sash as a courtesan approaches a client. The next example, also drawn from Jin Ping Mei, evocatively describes the entrance of four singing girls, each with “sash flying” in a seductive manner:

只見四個唱的一齊進來,向西門慶花枝颭招,繡帶飄飄,都插燭也似磕下頭去。

Thereupon, each of them:

Like a sprig of blossoms swaying in the breeze,

Sending the pendants of her embroidered sash flying,

Just as though inserting a taper in its holder,

proceeded to kowtow to him.Footnote88 [David Roy translation]

Shift in vocal register

During the first stage, direct dialogue with clients appears to have been relatively rare, and when courtesans used their voice (for instance, when greeting or performing a song), they would commonly adopt the strategy of lowering their voices to a quiet, subdued tone. This is because soft voices are associated with submissiveness, allowing the individual to convey an attractive, non-threatening image to attract positive engagement rather than repel or provoke.Footnote89 The following example, from the Ming era short story “Wu Qing Meets Ai’ai by Golden Bright Pond,” includes reference to a typically subdued greeting:

那三個正行之際,恍餾見一婦人, … … 覷著三個,低聲萬福。

As they were traveling, they became vaguely aware of the presence of a woman … … Casting a coy glance at the three young men, she chanted a greeting in a subdued voice.Footnote90 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

The same principle appears to have been commonly applied when singing. The next two examples describe Ming courtesans lowering their voices when singing for male clients, while providing their own instrumental accompaniment. Perhaps these courtesans were singing quietly not merely out of shyness; quiet singing tends to create a peaceful mood while encouraging onlookers to be still and focus keenly on the performer:Footnote91

這吳銀兒不忙不慌,輕舒玉指,款跨鮫綃,把琵琶在於膝上,低低唱了一回柳搖金。

Thereupon, [the courtesan] Wu Yin-erh: neither hastily nor hurriedly, deftly extended her jade fingers, gently strummed the silken strings, placed the pipa on her knees, and sang in a low voice a song to the tune “The Willows Dangle Their Gold”:

… …

那鄭春款按銀箏,低低唱清江引道 … …

… [The courtesan Cheng Ch’un] gently strummed the silver psaltery, and sang in a low voice a song to the tune “Clear River Prelude” … Footnote92 [David Roy translation]

The next example, again from Jin Ping Mei, provides a more comprehensive picture of the Ming courtesans’ first stage of seduction. Here, the female singer Li Guijie is appearing in front of the male protagonist for the first time, making full use of her body movements, hand movements, and prop (fan), as vehicles for signaling seduction. With a hint of faux coyness, she shows off her charm, seemingly effortlessly:

朝上席不當不正,只磕了一個頭,就用灑金扇兒掩面,佯羞整翠,立在西門慶面前。

Facing the seat of honor:

Neither correctly nor precisely,

she performed but a single kowtow, after which:

Hiding her face behind her gold-flecked fan,

While coyly adjusting her hair ornaments,

she took her stand in front of Hsi-men Ch’ing.Footnote93 [David Roy translation]

phase 2: interacting and developing intimacy

If the purpose of the first phase was to captivate the male guest’s amorous interests, then from the second phase, the focus turned to deepening the relationship. Here, conversations and interactions would unfold, the courtesan and male customer becoming better acquainted with each other and moving towards intimacy. To facilitate a narrowing of the psychological and emotional distance between the two, the courtesan would elicit moments of physical proximity—for example, through deliberate yet casual touches.

Conversation

According to behavioral studies scholarship, verbal communication is a necessary, integral component in the courtship process, though other forms of semantic exchange may also be used (including sign language, writing, and so on). However, according to Givens, the topic of a conversation itself seems to have limited relevance to the formation of a relationship, at least in the initial stages. Rather the way one communicates is more important than what is actually said.Footnote94 For heterosexual couples in the early stages of courtship, the connection is said to thrive when women take center stage and participate prominently in the conversation while men show approval and understanding.Footnote95 Givens suggests that the anxiety accompanying courtship invariably increases the frequency of certain behaviors during conversation—preening, nodding approvingly, stretching, throat clearing, and other adjusting actions.Footnote96 For example, when one partner is stating a point, the other often nods their head in exaggerated agreement to encourage further communication and prevent awkward pauses. Some scholars suggest that conversations in courtship typically show a kind of asymmetry in which the rhythmic give-and-take is determined through negotiation.Footnote97 When handled sensitively by both parties, conversation tends to play a major role in establishing a benign and harmonious relationship.

For the courtesan-guest relationship, too, conversation would have been an integral element in the courtship process, essential for establishing a trusting bond between parties—though in this case, of course, the conversation would often be condensed into a very short period (typically one night) and the bond would often be of a transient, short-term nature. Through conversation, essential information would be exchanged, attractive skills and attributes would be displayed (wit, sensitivity, creativity, and so on), and both parties would gain insights into their emotional states and desires. Conversation was clearly an essential tool of seduction. A typical example of conversation between a courtesan and a guest is shown in . The picture shows a courtesan and male guest sitting at a table, both smiling, with a screen painted with natural scenery behind them. From the rocks and plants, it can be inferred that this is a semi-open garden in a brothel or a private house, with the screen providing a certain degree of concealment.

Fig. 4. Tanxin Tu 談心圖 “A heart-to-heart talk.”Footnote119 The words on the right indicate the courtesan’s ranking: “Third in the Second class.” In the middle of the garden, a courtesan and a male scholar who holds a folding fan sit facing each other, with a folding screen behind them.

Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.

![Fig. 4. Tanxin Tu 談心圖 “A heart-to-heart talk.”Footnote119 The words on the right indicate the courtesan’s ranking: “Third in the Second class.” In the middle of the garden, a courtesan and a male scholar who holds a folding fan sit facing each other, with a folding screen behind them.Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.](/cms/asset/80fdac0a-5393-4018-9eed-db44fca1f99b/ymng_a_2249327_f0004_oc.jpg)

Conversations between courtesans and guests could obviously occur at any stage of the courtship process, but they were concentrated in the second stage, as an effective means for developing deeper interpersonal understanding and trust and establishing a mood conducive for physical intimacy (stage three). The following passage, from the short fiction “Secretary Qian Leaves Poems on the Swallow Tower,” details the beginning of a conversation between a courtesan and her guests, after she has given a musical performance that has successfully attracted their attention. Here, she is portrayed as not only beautiful and elegant in her movements; she also has advanced conversational skills, which she exploits to ensure that the interaction proceeds smoothly and enjoyably:

遂呼而問曰:「孰氏?」其妓斜抱胡琴,緩移蓮步,向前對曰:「賤妾關盼盼也。」 … … 建封曰:「誠如舍人之言,何惜一詩贈之?」樂天曰:「但恐句拙,反汙麗人之美。」盼盼 … ..言:「妾姿質醜陋,敢煩珠玉?若果不以猥賤見棄,是微軀隨雅文不朽,豈勝身後之榮哉。」

They called the pipa player forth and asked, “What is your name?”

The pipa aslant in her arms, the courtesan took a few delicate, mincing steps forward and replied, “My humble name is Guan Panpan.”

… …

“It is indeed as you say,” said Jianfeng. “You will not begrudge composing a poem in her honor?”

“I’m afraid only that my clumsy lines will be an insult to her beauty.”

Guan Panpan … … said, “With my uncomely looks, I would not dream of winning a jewel of a poem in my name, but if you, sir, do not find it beneath your dignity to write on such a lowly subject, your immortal poem will lend me some glory after I am gone, however insignificant I am.”Footnote98 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

In Ming period fiction, we often encounter descriptions of courtesans who first establish a bond with their guest through artful phatic communicationFootnote99 and then open their hearts and express secret feelings and thoughts, often accompanied by the act of crying. Now that private emotions have been revealed, the interpersonal bond has become both special and tight, prompting various commitments, sometimes including marriage. However, the courtesan’s expressions of private emotions, thoughts, and promises are often depicted in an ambiguous light: we are not sure how much they express her true sentiments of the moment and how much they are seductive strategies to further ensure continuing loyalty and custom. For instance, in the upcoming example, drawn from the short story “The Oil-Peddler Wins the Queen of Flowers,” we do not know to what extent the courtesan Sister Mei’s promises to Qin Zhong and her tears are sincere:

… … 美娘道:「我要嫁你。」秦重笑道:「小娘子就嫁一萬個,也還數不到小可頭上,休得取笑,枉自折了小可的食料。」美娘道:「這話實是真心,怎說取笑二字!我自十四歲被媽媽灌醉,梳弄過了。此時便要從良, … … 看來看去,只有你是個誌誠君子,況聞你尚未娶親。若不嫌我煙花賤質,情願舉案齊眉,白頭奉侍。你若不允之時,我就將三尺白羅,死於君前,振白我一片誠心, … … 」說罷,嗚嗚的哭將起來。

“I want to marry you,” said Sister Mei.

Qin Zhong laughed. “Even if you marry ten thousand men, I won’t be able to make the list. Don’t tease me. You’ll only make the gods cut my life short.”

“I mean it. How can you say I’m teasing you? I was fourteen when the madam got me drunk and made me take my first patron. Ever since then, I’ve wanted to marry and get out of this business … … Of all the men I’ve met, you are the only trustworthy one. I’ve also heard that you are still single. If you don’t look down on me because of my lowly profession, I will be more than happy to serve you as your wife for the rest of my life. If you turn me down, I will strangle myself with a three-foot-long piece of white silk and die at your feet to prove my sincerity. … … ” So saying, she started to weep.Footnote100 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

… … 公子和十娘坐於舟首。公子道:「自出都門,困守一艙之中,四顧有人,未得暢語。今日獨據一舟,更無避忌。且已離塞北,初近江南,宜開懷暢飲,以舒向來抑郁之氣。恩卿以為何如?」十娘道:「妾久疏談笑,亦有此心,郎君言及,足見同誌耳。」公子乃攜酒具於船首,與十娘鋪氈並坐,傳杯交盞。

Sitting at the bow with Shiniang by his side, Li said, “Ever since we left the capital, we’ve been cooped up in a cabin with other people all around us and never had a chance for a good talk. Now, with a boat to ourselves, we can finally disregard all scruples. Since we’ve left the north and are approaching the south side of the Yangzi River, let’s drink to our hearts’ content to shake off the gloom of the last few days. What do you say?”

“I was thinking along the same lines, because I, too, miss having a good talk and a good laugh. Your bringing this up shows that we are truly of the same mind.” Li fetched wine utensils, spread out a rug on the bow, and sat down shoulder to shoulder with Shiniang. They began passing the cups back and forth.Footnote103 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

Touching

Touch, or haptic communication, is a common component of courtship and has a powerful emotional impact. Research has shown that touch can contribute to feelings of comfort, warmth, love, and closeness, and is a core component of enhancing human intimacy.Footnote104 Because there is a large amount of skin contact involved in sexual intercourse, any brief touch can be symbolic and powerful.Footnote105 As Judith Hanna explains, in American strip clubs (and various other related contexts), both touching between performers and touching between performer and customer are frequently used to stimulate desire.Footnote106 In the Ming era courtship context, touch appears to have been relatively sparse in the early stages, in accordance with social fashion and cultural norms. However, touching clearly did take place, especially prior to the stage of sexual intimacy, because of its ability to rapidly promote lust. For example, shows a courtesan drinking and cuddling with a man in the garden.

Fig. 5. Jiaohuan Tu 交歡圖 “An Illustration of Pleasure.”Footnote120 The words on the right state: “Eleventh in the second class, Xiang Ruyu 項如玉.” Ruyu is the courtesan on the left, sitting together with a male guest in a garden surrounded by rocks, flowing water, and plants. They sit at a banquet table with drink and food, the man holding a wine glass in his left hand and wrapping his right arm around her shoulder. The courtesan sits on his lap with a glass in her left hand. The two are smiling and facing each other.

Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.

![Fig. 5. Jiaohuan Tu 交歡圖 “An Illustration of Pleasure.”Footnote120 The words on the right state: “Eleventh in the second class, Xiang Ruyu 項如玉.” Ruyu is the courtesan on the left, sitting together with a male guest in a garden surrounded by rocks, flowing water, and plants. They sit at a banquet table with drink and food, the man holding a wine glass in his left hand and wrapping his right arm around her shoulder. The courtesan sits on his lap with a glass in her left hand. The two are smiling and facing each other.Source: Wanyuzi 宛瑜子. Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area]. Beijing: Beijing Library Press, 2002.](/cms/asset/5f2eed75-3b13-4e72-b3f3-76636ace107a/ymng_a_2249327_f0005_oc.jpg)

The motivating power of touch is amply illustrated by the following extract, taken from the Ming short story “Yutang Chun Reunites with Her Husband in Her Distress.” Here, the brothel madam urges a courtesan to sit side by side with the male guest as drinks are served:

鴇兒幫襯,教女兒捱著公子肩下坐了,吩咐丫鬟擺酒。 … … 公子開懷樂飲。

To move matters along, the madam made the girl sit down by the young man’s shoulder. She then ordered maids to set out wine. … … Amid strains of music, the young master was drinking to his heart’s content.Footnote107 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

公子與玉姐肉手相攙,同至香房,只見圍屏小桌,果品珍羞,俱已擺設完備。

Hand in hand, the young man and Sister Yu went to the latter’s boudoir, where a small table, shielded by a folding screen, was laid out with fruit and delicacies.Footnote108 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

隨與錢貴攜手進房,見房中焚蘭熱麝,幽雅非常,繡帳錦衾,又富麗至極。

Then, hand in hand, Zhong Sheng [the male client] and Qian Gui [the courtesan] came into the room. Behold: The burning incense heats up the room, setting off the elegant surroundings. The embroidered bed nets and the brocaded quilt are splendid.Footnote109

Of course, courtesans and their guests would have physically engaged with their clients via a wide variety of contact patterns, extending beyond merely the shoulder and hand regions. , for example, suggests some other types of interaction that could typically have characterised this stage of courtship. While the other guests are drinking, Ximen Qing (the main protagonist of Jin Ping Mei, wearing pastel green clothing) is hugging a courtesan (dressed in red) who sits on his lap. He is feeding her a cup of wine with his left arm around her. Meanwhile, her left hand is lightly wrapped around his wrist, and she looks down shyly while he squints, smiles, and gazes at her face. Their head positions are close, evidencing growing intimacy.

Multisensory seduction

Before moving on to my final remarks, it is worth highlighting a striking characteristic that typically pervades Ming period descriptions of the courtesans’ practices—running through all four courtship phases and featuring prominently in the many examples presented above—namely, the richly multisensory nature of the experience. Typically, we see the courtesans executing their seduction through a wide range of sensory channels in close conjunction, appealing to men’s desires in the visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, and tactile realms. As Sara Pink compellingly argues, all experience is inherently multi-sensory in nature and, accordingly, our scholarly enquiries should seek to identify the complete sensory picture rather than homing in a single dimension.Footnote110 Fortunately, this is easily accomplished in the case of Ming courtesanship studies: the authors of that period appear to have been highly sensitive to the various sensory components in the brothel’s multi-sensory world, pinpointing the most potent sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches that served to affect the desired responses.

Fig. 6. “Master Ximen Accepts the Service of Courtesan Cinnamon Bud” 西門慶疏籠李桂姐,Footnote121 depicting an indoor drinking banquet scene.

Source: “Master Ximen Accepts the Service of Courtesan Cinnamon Bud 西門慶疏籠李桂姐(金瓶梅插畫冊).” The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, eighteenth century. Album leaf, ink and color on silk.

The following example, drawn from the short story “Secretary Qian Leaves Poems on the Swallow Tower,” amply illustrates this rich multi-sensory quality:

當時酒至數巡,食供兩套,歌喉少歇,舞袖亦停。忽有一妓,抱胡琴立於筵前,轉袖調弦,獨奏一曲,纖手斜拈,輕敲慢按。滿座清香消酒力,一庭雅韻爽煩襟。須臾彈徹韶音,抱胡琴侍立。

After several rounds of wine and two food courses, the singing came to a halt, and the sleeves of the dancers stopped waving. There emerged in front of the feast table a courtesan holding a pipa in her arms. After tuning the instrument, she began playing solo, her dainty fingers gently tapping, pressing, and plucking at the strings. A delicate fragrance dispelled the effects of the wine, and the refined notes of the music dissolved all worries. In a short while, she stopped playing and stepped to one side, her pipa in her arms.Footnote111 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

鳳撥金鈿砌,檀槽後帶垂。

醉嬌無氣力,風裊牡丹枝。

The phoenix plucks at the bejeweled zither,

With ribbons behind the sandalwood grooves.

In soft breezes, as if tipsy with wine,

The wind flutters the peony on the branch.Footnote112 [Shuhui Yang and Yunqing Yang translation]

Although this poem may initially seem to have little connection with the courtesan, the phoenix is in fact a metaphor for the talented courtesan herself, symbolizing luxury, nobility, and rarity. Here, the “phoenix” plucks the jewel-encrusted zither to create an enchanting sound, while the sandalwood and peony contribute scent and the soft breeze brings a tactile sensation. In keeping with the preceding banquet scene, wine is also mentioned here, stimulating taste sensations and tipsiness.

Some Concluding Observations

This research has sought to identify, classify, and explicate the range of seduction strategies that Ming era courtesans employed. Given the nature of the courtesan profession, it is not surprising that these women devoted a great deal of care and time to the cultivation of seductively appealing qualities. Extending beyond skillfully selecting clothing and accessories to complement their physical attributes, there was clearly much to benefit from developing skills in conversation and the arts, and from learning how to use their voices and bodies to communicate intentions and guide interaction in particular directions. Indeed, the development of strong skills in reading and applying diverse forms of seductive signaling must have been critically important to them, being directly linked to their professional success. Such skills would have enabled them to surpass the competition, navigate difficult conflict-ridden interactions, and successfully manipulate others’ emotions in ways that would benefit them personally—these clearly being central areas of concern within the realm of courtesanship, as they are in courtship more generally.Footnote113

As demonstrated above, Ming period writers tended to depict the courtesans’ behavior as carefully designed and premeditated down to the smallest detail, and furthermore, as almost always geared towards seductive ends. This surely reflected the male authors’ own interpretations and their tendency to conform to literary stereotypes. However, in reality, the courtesans would often have been able to carry out their interactions with very little conscious calculation. After years of immersion in their profession, they would often have been able to rely on well-honed intuition and behavioral patterns that had become almost hard-wired into their beings through repetition. Each different courtesan would also have developed their own individual persona, characterized by certain attire and makeup, vocal attributes, skills, and sets of preferred seductive strategies. The distinctiveness of each courtesan’s charms is, indeed, often highlighted in Ming period sources, such as the forementioned Wu Ji Bai Mei 吳姬百媚, the volume of “prostitutes” 妓部 in Wang Shizhen’s 王世貞 novel Yan Yi Bian 艷異編 (A Collection of Luscious and Indulgent Love Affairs),Footnote114 and Ban Qiao Za Ji板橋雜記 (Miscellaneous Records of the Plank Bridge) by Yu Huai 余懷.Footnote115 So, while some courtesans may have been notably Machiavellian in their approach, others would have thrived on account of contrary qualities, such as sincerity and outspokenness. It is also worth noting that each courtesan would surely have developed a complex, multi-faceted nature, as people generally do. As narratives like Jin Ping Mei suggest, each courtesan would have adapted her conduct and strategies according to the needs of the moment. Evidently, there remains much more to uncover in this field of enquiry, through consulting other Ming period sources while also extending the coverage to consider subsequent seduction phases (lovemaking and the post-passion transition back to mundane interaction).

To explore this topic, I have adopted an interdisciplinary approach, applying insights gleaned from the field of behavioral studies to shed light on Ming period courtesanship practices as described in novels, poems, and other documents. Consulting the former scholarship has greatly aided the process of identifying and interpreting the courtesans’ strategies, and it is intriguing to see how, again and again, the key behaviors identified by scholars like Albert Scheflen, Desmond Morris, David Buss, and Judith Hanna are evocatively depicted in the old documents. Evidently, as behavioral scholarship postulates, much courtship behavior is near-universal in its reach, spanning diverse cultures and periods. In Ming period China, seduction was achieved through preening, posture preparation, flirtatious emphasis of certain body parts, suggestive dialogue, use of touch, and a wide variety of other methods. One might expect to see a wealth of parallel practices pervading other courtesan cultures also, although this hypothesis would need to be substantiated through equivalent interdisciplinary research.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shiyun Wang

Shiyun Wang is a PhD candidate at Durham University, major in music. Her research interests lie in historical ethnomusicology, with a particular focus on the music-making of Chinese Ming period courtesans.

Notes

1 Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan: Veronica Franco, Citizen and Writer in Sixteenth-Century Venice, 7; Berg, “Amazon, Artist, and Adventurer: A Courtesan in Late Imperial China,” 15.

2 McMahon, “The Pornographic Doctrine of a Loyalist Ming Novel: Social Decline and Sexual Disorder in Preposterous Words (Guwangyan),” 58–65. Also see: Li, “The Late Ming Courtesan: Invention of a Cultural Ideal,” 46–73; Wetzel, “Hidden Connections: Courtesans in the Art World of the Ming Dynasty,” 659. Li delves into how and why courtesans became a projection of the cultural ideals of the late Ming literati, while Wetzel argues that the high status enjoyed by courtesans in Ming urban society was partly due to their positive depiction in popular literature and the visual arts, where sometimes they were ironically presented as models of virtue.

3 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Gua zhi’er shan’ge jia zhutao min’ge sanzhong 掛枝兒山歌夾竹桃: 民歌三種 [Gua zhi’er, shan’ge, jia zhutao: Three Types of Folk Songs], 50. Unless otherwise noted, the English translations in this article were done by the current author. If translations by others are used, they are specifically noted in the endnotes.

4 Another songbook compiled by Feng Menglong is Shan’ge 山歌 (Mountain Songs), a collection of folk songs from the Suzhou region. The theme of the songs is mostly about love, a large part of which depicts illicit but passionate love (siqing 私情 “secret love”). Ōki, “Wanton, but Not Bad: Women in Feng Menglong’s Mountain Songs,” 129; Ōki, “Women in Feng Menglong’s Mountain Songs” 131–37.

5 Ko, “The Written Word and the Bound Foot: A History of the Courtesan’s Aura,” 88.

6 For study relating to Ming era imperial concubines, see: Hua, Concubinage and Servitude in Late Imperial China; McMahon, Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing.

7 Brook, The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, 112–13.

8 Ko, “Transitory Communities: Courtesan, Wife, and Professional Artist,” 293. Also see: Zurndorfer, “Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Confucian Moral Universe of Late Ming China (1550–1644),” 199–200.

9 Wang and Zhang, “Feng Menglong Shan’ge zhong yunhan de zhuqing sixiang zhi guankui 馮夢龍《山歌》中蘊含的‘主情’思想之管窺 [A Peek into Feng Menglong’s Thought of ‘Qing’ Contained in ‘Mountain Songs’],” 88; Zurndorfer, “Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Confucian Moral Universe of Late Ming China (1550–1644),” 208–13.

10 Feng, “Feng Menglong qingjiao sixiang yu sanyan bianzhuan 馮夢龍‘情教’思想與‘三言’編撰 [Feng Menglong’s Thought of ‘Love’ and the Compilation of ‘Sanyan’],” 32; Chu, “Cong xiaoshuo yu xiqu de bijiao shijiao kan Feng Menglong de qingjiao sixiang 從小說與戲曲的比較視角看馮夢龍的“情教”思想 [On Feng Menglong’s ‘Cult of Emotion’ Thought from the Comparative Perspective of Novels and Dramas],” 152.

11 Ōki, “Women in Feng Menglong’s Mountain Songs,” 138–39.

12 Peng, “The Music Teacher: The Professionalization of Singing and the Development of Erotic Vocal Style During Late Ming China,” 287.

13 Zhu Yuanliang 朱元亮 and Zhang Mengzheng張夢徵, Qinglou yunyu 青樓韻語 [Amorous Words in the Green House] [1616], 37.

14 Gulik, Sexual Life in Ancient China: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from ca. 1500 B.C. till 1644 A.D., 308–11; Hsu, “Courtesans and Scholars in the Writings of Feng Menglong: Transcending Status and Gender,” 76–77. Van Gulik incisively points out that brothel culture had a huge influence on the cultural and artistic fields of the Ming era Jiangnan area. This is because Ming gentry-literati, writers, and artists frequented the pleasure quarters in the Qinhuai River region of Jiangnan, where courtesans and prostitutes lived in lavish boats called hua fang 畫舫 (painted boats). Hsu Pi-Ching discusses the Ming era popular romantic narrative of the unrecognized scholars and the faithful courtesans.

15 Mann, “Entertainment,” 121–42.

16 Ropp, “Ambiguous Images of Courtesan Culture in Late Imperial China,” 18.

17 Ko, “Transitory Communities: Courtesan, Wife, and Professional Artist,” 251–93; also see Wetzel, “Hidden Connections: Courtesans in the Art World of the Ming Dynasty,” 664.

18 Bossler, “Shifting Identities: Courtesans and Literati in Song China,” 5–37; Bossler, “Floating Sleeves, Willow Waists, and Dreams of Spring: Entertainment and Its Enemies in Song History and Historiography,” 5.

19 Ko, “Transitory Communities: Courtesan, Wife, and Professional Artist,” 256; Tseng, “Women Painters of the Ming Dynasty,” 250.

20 Li Yu 李漁, Xian qing ou ji 閑情偶寄 [Sketches of Idle Pleasures] [1671], 273–74.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Wu ji bai mei 吳姬百媚 is a Ming era collection of poems, songs and illustrations themed on the courtesans in Suzhou area. Wanyuzi 宛瑜子, Wu ji bai mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou area].

24 To list a few studies: Davis, Inside Intuition: What We Know About Nonverbal Communication; Eibl-Eibesfeldt and Strachan, Love and Hate: The Natural History of Behavior Patterns; Mehrabian, Nonverbal Communication; Guerrero and Floyd, Nonverbal Communication in Close Relationships.

25 Barendregt, “The Changing Art of Seduction: Ritual Courtship, Performing Prostitutes, Erotic Entertainment,” 4.

26 Hanna, “Empowerment: The Art of Seduction in Adult Entertainment Exotic Dance,” 203–15.

27 Music, Dance and the Art of Seduction, i.

28 Moore, “Human Nonverbal Courtship Behavior—A Brief Historical Review,” 171.

29 Stevenson, Oxford Dictionary of English, 29942.

30 Xin hua zi dian 新華字典 [Xinhua Dictionary], 595.

31 Excerpted from the Chinese rime dictionary, Guangyun 廣韻, compiled from 1007 to 1008 under the patronage of Emperor Zhenzong of Song, edited by Chen Pengnian 陳彭年 (961–1017) and Qiu Yong 邱雍. See: Baxter, A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, 38–39.

32 Confucius 孔子, The Analects of Confucius (Chinese–English Bilingual Edition) 論語今譯 漢英對照, 92–93.

33 Han Yu 韓愈, Zhu Xi 朱熹, Wang Boda 王伯大, and Zhu Wubi 朱吾弼, Zhu Wen Gong Jiao Changli Xian Sheng Wen Ji 朱文公校昌黎先生文集.

34 Hanna, “Empowerment: The Art of Seduction in Adult Entertainment Exotic Dance,” 200.

35 Stevenson, Oxford Dictionary of English, 7381.

36 Givens, Love Signals: A Practical Field Guide to the Body Language of Courtship, 34–35.

37 Sima Qian 司馬遷, Shiji 史記 [Historical Records], 1389–90.

38 Givens, Love Signals: A Practical Field Guide to the Body Language of Courtship.

39 Bailey, From Front Porch to Back Seat: Courtship In Twentieth Century America, 6.

40 Scheflen, “Quasi-courtship Behavior in Psychotherapy,” 247–8.

41 Birdwhistell, Kinesics and Context: Essays on Body-Motion Communication, 158–79.

42 Morris, Intimate Behavior, 74–79.

43 Lockard and Adams, “Courtship Behaviors in Public: Different Age/Sex Roles,” 245–53.

44 Jesser, “Male Responses to Direct Verbal Sexual Initiatives of Females,” 122–23.

45 Perper and Weis, “Proceptive and Rejective Strategies of US and Canadian College Women,” 462–78; Clark et al., “Strategic Behaviors in Romantic Relationship Initiation,” 709.

46 Buss, The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating, 1–5.

47 Eibl-Eibesfeldt and Strachan, Love and Hate: The Natural History of Behavior Patterns, 50.

48 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Gua zhi’er shan’ge jia zhutao min’ge sanzhong 掛枝兒山歌夾竹桃: 民歌三種 [Gua zhi’er, shan’ge, jia zhutao: Three Types of Folk Songs].

49 Roy, The Plum in the Golden Vase or, Chin P'ing Mei 金瓶梅.

50 Wanyuzi 宛瑜子, Wu ji bai mei 吳姬百媚 [Seductive Courtesans in Suzhou Area].

51 Scheflen, “Quasi-courtship Behavior in Psychotherapy,” 247–48.

52 Ibid.

53 Roy, The Plum in the Golden Vase or, Chin P’ing Mei, Volume Two: The Rivals, 254–55.

54 Scheflen, “Quasi-courtship Behavior in Psychotherapy,” 247–48.

55 Roy, The Plum in the Golden Vase or, Chin P'ing Mei, Volume Three: The Aphrodisiac, 496.

56 Zhongguo quxue da cidian 中國曲學大辭典 [Dictionary of Chinese Qu Study], 5.

57 Peng, “Courtesan vs. Literatus: Gendered Soundscapes and Aesthetics in Late-Ming Singing Culture,” 405–11.

58 Che and Liu, “‘Xiaochang’ kao ‘小唱’考 [On Discussion of Xiaochang],” 186.

59 Wang et al., Qulü zhushi 曲律註釋 [Notes on Rules of Qu]. See also: Zeitlin, “‘Notes of Flesh’ and the Courtesan’s Song in Seventeenth-Century China”; Peng, “Courtesan vs. Literatus: Gendered Soundscapes and Aesthetics in Late-Ming Singing Culture,” 412–13; Peng, Lost Sound: Singing, Theatre, and Aesthetics in Late Ming China, 1547–1644.

60 Yu Huai 余懷, “Miscellaneous Records of the Plank Bridge 板橋雜記 [1693],” translated by Li Wai-yee, 93–94.

61 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Gua zhi’er shan’ge jia zhutao min’ge sanzhong 掛枝兒山歌夾竹桃: 民歌三種 [Gua zhi’er, shan’ge, jia Zhutao: Three Types of Folk Songs], 103.

62 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Stories to Awaken the World 醒世恆言 [1627], translated by Yang Shuhui and Yang Yunqing, 69–70.

63 Scheflen, “Quasi-courtship Behavior in Psychotherapy,” 247.

64 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Stories to Caution the World 警世通言 [1624], translated by Yang Shuhui and Yang Yunqing, 143.

65 Gersick and Kurzban, “Covert Sexual Signaling: Human Flirtation and Implications for Other Social Species,” 549.

66 Gersick and Kurzban, “Covert Sexual Signaling: Human Flirtation and Implications for Other Social Species,” 549. For research on flirting among primates, see: Botero, “Primates are Touched by Your Concern: Touch, Emotion, and Social Cognition In Chimpanzees,” 372–80; Walker-Bolton and Parga, “‘Stink Flirting’ in Ring-Tailed Lemurs (Lemur catta): Male Olfactory Displays to Females as Honest, Costly Signals,” 1, 9.

67 Feng Menglong 馮夢龍, Stories Old and New 古今小說 [1620], translated by Yang Shuhui and Yang Yunqing, 510.