?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this paper, we explore the implications of audit office distraction for audit effort and quality. We hypothesise that an audit office with financially distressed clients (i.e. a distracted auditor) faces greater time pressures and pays less attention to the audits of the remaining non-distressed clients in their portfolio. If an audit office is distracted, they will have less bargaining power over their audit fees; and non-distressed clients will have greater incentives to engage in earnings management given the reduced expected intensity of professional skepticism. We use the ratio of audit fees derived from financially distressed clients to total audit fees of the audit office to provide strong support for these hypotheses in a sample of US firms over the period 2000–2019. Specifically, we find that distracted auditors have longer delays in issuing audit reports and lower audit fees. When the level of distraction is high, non-distressed clients engage more in accrual and real earnings management and have relatively lower earnings response coefficients. Our results are robust to using entropy balancing, audit firm fixed effects, alternative measures of distraction, and a placebo test addressing mechanical bias and randomness effects. Further analysis indicates that audit firm tenure, and audit office size and industry specialisation reduce the negative effects of distraction on audit fees and audit delay. Overall, our results provide new insights on how auditor distraction affects clients’ earnings quality due to reduced effort.

1. Introduction

A growing body of auditing literature examines how the characteristics of the audit office influence their clients’ reporting environment (see e.g. Beck et al., Citation2019; Bills et al., Citation2016; Francis & Michas, Citation2013; Whitworth & Lambert, Citation2014). We extend this literature by examining how the level of distraction of the audit office that results from limited attention and time pressures influences their audit effort and their clients’ earnings quality. We argue that when an audit office has a subset of clients that require a significant amount of attention and resources, their capability to effectively audit their other clients is hindered. Our focus is on a subset of clients within the same audit office that distracts auditors and generates time pressures. Specifically, we contend that financially distressed clients necessitate greater attention and professional skepticism from auditors and therefore constitute a potential group of clients that can temporarily stress the audit office resources. The literature on corporate financial distress supports this argument and shows that managers engage in deceptive reporting during times of financial difficulties to avoid violating debt covenants or to maximise their short-term compensation (Efendi et al., Citation2007; Sweeney, Citation1994).

Since financially distressed clients are more prone to using complex earnings management methods, auditors must exercise a greater degree of professional skepticism and audit effort to ensure that audits are effective and audit risk is at a tolerable level. However, an audit office typically reserves an economically optimal level of resources for the audits of a portfolio of clients that means that their staff risks being distracted and their resources being spread too thin when allocating more attention to distressed clients. Consequently, non-distressed clients are more likely to be affected by reduced earnings quality due to less effort by auditors. We also hypothesise that given increased time pressure and lower bargaining power, distracted auditors take longer to issue audit reports and charge lower audit fees to their non-distressed clients. The confounding effect of lower attention and audit effort from auditors results in client firms engaging in more income-increasing earnings management.

Empirically, we create our measure of distraction by using the level of exposure of the audit office to financially distressed clients. Specifically, we measure distraction at the office level as the ratio of audit fees derived from financially distressed clients to total audit fees. We define audit clients as financially distressed if their financial distress score based on Kaplan & Zingales’ (Citation1997) index (hereafter, KZ index) is in the top quintile among all Compustat firms in a given year.Footnote1 There are two advantages to using the KZ index. First, non-distressed clients of an audit office are highly unlikely to affect the financial position of distressed clients. The non-distressed clients, therefore, experience the audit office’s distraction largely exogenously. Second, clients in the top quintile of the KZ index must either overcome financial hardship or file for bankruptcy. In either case, our measure of distraction changes, introducing meaningful variability.

To test our hypotheses, we use a sample of publicly listed US firms from 2000–2019. We delete financially distressed firms and only concentrate on non-financially distressed ones. Following prior research, we control for several client, auditor, and audit office characteristics and estimate our regressions using audit firm, industry, and year fixed effects. Consistent with our predictions, distracted auditors pay less attention to the audits of non-financially distressed clients. Specifically, we find that distraction is associated with longer audit delays and lower audit fees. The results are also economically significant. All else being equal, when auditors are distracted, they tend to take 3.3 percent more time to issue audit reports than in the previous year. Similarly, when audit offices are distracted, they receive 1.5 percent lower audit fees than in the prior year. In the entropy-balanced sample, distracted audit offices take 0.7 percent more time and receive 1.9 percent lower audit fees.

We next examine whether the distraction of audit offices increases the probability of engaging in income-increasing earnings management by clients. Following prior evidence, we measure discretionary accruals using the Jones (Citation1991) model as modified by Dechow et al. (Citation1995) and the Dechow and Dichev (Citation2002) as modified by McNichols (Citation2002). To measure real earnings management, we rely on a measure of abnormal discretionary expenses introduced by Roychowdhury (Citation2006). Our analysis shows that across all three models, distracted audit offices are positively associated with income-increasing earnings management by clients. In distracted years, client firms tend to inflate their earnings by 0.2–0.3 percent of total assets. Further, they reduce discretionary expenses by approximately 0.6 percent of total assets when compared to non-distracted years. Lastly, we analyze how stock prices react to earnings contingent on distraction. To implement this test, we follow Hackenbrack and Hogan (Citation2002) and rely on annual earnings announcements and calculate earnings surprises as the difference between current and previous year earnings deflated by the previous year’s stock price. Our results show that auditor distraction lowers the non-distressed clients’ earnings response coefficients. Keeping all else equal, for a typical earnings surprise of 0.016 relative to the stock price in the previous year, the cumulative abnormal returns around the earnings announcement date are 2.69 percent lower for clients of distracted audit offices compared to clients of non-distracted audit offices. This result is consistent with the idea that the market perceives the earnings quality of non-distressed clients as relatively less informative.

Our results are robust to several different specifications addressing measurement error and endogeneity. Since observable firm characteristics may be correlated with audit effort and the earnings quality of clients, our results could be driven by the endogenous matching of a distracted audit office and a client that possesses those characteristics. To mitigate this concern, we use entropy balancing to achieve covariate balances that are virtually identical in the first and second moments (i.e. mean and variance). Using this technique, we re-estimate our main results. Our findings remain qualitatively unchanged. We also implement a placebo test to address mechanical bias and randomness effects. To do this, we randomly assign distraction scores to audit offices annually and re-estimate our models using 1,000 simulations. The coefficients obtained from this analysis are different and statistically insignificant compared to our main results. This process indicates that our results are not driven by mechanical bias or randomness in the data.

Our findings also indicate that distraction is temporary, and once the audit office can allocate more resources to the remaining clients, the negative implications disappear. In cross-sectional analyses, we test three variables that can potentially mitigate the negative effects of distraction on the audit effort and the earnings quality of clients. First, we test the effects of audit office size. Since large offices have more resources and better quality audits in general (Francis & Yu, Citation2009), we expect them to be less prone to time pressures and have more bargaining power. Consistent with this argument, we find that audit office size reduces the negative effect of distraction on audit fees but does not affect the relation between distraction and audit delay. Second, based on the previous literature (e.g. Casterella et al., Citation2004; Fung et al., Citation2012), we argue that the industry specialisation of audit offices can help them overcome some of the challenges presented by distraction. Our results indicate that industry specialisation helps reduce audit report delay when the audit offices are distracted, but it does not affect audit fees. Finally, we test the effects of audit firm tenure on audit effort and find that tenure helps reduce audit report delay and increase audit fees. Overall, these findings are consistent with prior evidence on audit office characteristics and audit effort.

We make several contributions to the literature. First, we extend the literature on audit office characteristics that affect audit quality. Prior research shows that audit office size (Francis et al., Citation2013; Francis & Yu, Citation2009), industry specialisation (Casterella et al., Citation2004; Fung et al., Citation2012), solvency and client visibility (Gaeremynck et al., Citation2008), growth (Bills et al., Citation2016), client deadline concentration (Czerney et al., Citation2019), geographical decentralisation (Beck et al., Citation2019), and labour market proximity (Lee et al., Citation2022) affect audit quality. We find that auditor distraction resulting from clients’ financial constraints compels an audit office to allocate more effort to the audits of certain clients and to, consequently, pay less attention to the audits of the remaining clients. As a result, the audit office takes longer to issue its audit report and charges lower audit fees, non-distressed clients engage more in income-increasing earnings management, and investors react less intensely to earnings information.

Our findings also relate to the literature on workload compression (López & Peters, Citation2012), auditor busyness (Goodwin & Wu, Citation2016), and audit time pressure (Lambert et al., Citation2017). However, unlike studies on workload compression and busyness, we define distraction using a subset of clients of the audit office and show that even after controlling for these traditional measures of busyness, the effect of distraction on audit effort and the earnings quality of the clients is incremental. Similarly, our study differs from Lambert et al. (Citation2017) because we do not rely on a single event that temporarily stresses auditors. Instead, our measure of distraction has meaningful variation over time, and we show that this variation is related to the earnings quality of clients and the response of investors.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: In the next section, we discuss the available theory and formulate hypotheses. After that, we present our sample and research design. There then follows a section in which we present our results. The concluding section summarises our findings, and the appendix has definitions of the variables.

2. Related literature and hypothesis development

2.1. Time pressure and audit quality

Experimental and survey-based evidence indicates that auditors may not apply a critical mindset and evaluate evidence thoroughly when they face increased time pressure during audits. For instance, in an experimental setting, McDaniel (Citation1990) finds that time pressure increases audit efficiency but decreases audit effectiveness. Other studies show that time budget constraints result in more premature sign-offs – signing off on an audit program step without fully completing all the required audit tasks (Alderman & Deitrick, Citation1982; Otley & Pierce, Citation1996; Willett & Page, Citation1996). Similarly, Asare et al. (Citation2000) find that time pressures negatively affect the extent (number of tests to conduct) and depth (number of potential hypotheses to test) of testing. In an experimental study, Braun (Citation2000) shows that under time pressure, auditors are likely to focus on the quantitative aspects of misstatements while paying less attention to the qualitative indicators that could signal fraudulent financial reporting.

Consistent with this evidence, Nelson (Citation2009) argues that time pressure can negatively affect auditors’ professional skepticism by motivating them to prioritise efficiency over effectiveness and altering the types of decision-making that an auditor uses when approaching a task. More recently, Lambert et al. (Citation2017) exploit a change in a rule of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) that imposes time pressure on audits of registered firms and find that exogenous shocks resulting in more time pressures on auditors impair the quality of the audits of treated firms. Lambert et al. (Citation2017) also survey retired audit partners to provide further evidence on the challenges of increased time pressure in the auditing process. Oversight bodies also recognise the impeding effects of time constraints on professional skepticism (e.g. PCAOB, Citation2012).

2.2. Limited attention and the framework for auditor distraction

Researchers in cognitive psychology put forth the limited attention hypothesis, which posits that human attention is a finite resource with limited capacity. Since humans can only attend to a limited amount of information at any given time, they must selectively focus their attention on a subset of information while ignoring or filtering out other information (Cherry, Citation1953; Kahneman, Citation1973). Studies in auditing rely on this framework and argue that audit offices have limited attention, effort, and resources to devote to their clients. Consequently, audit partners and offices perform poorly when they audit many clients (Gul et al., Citation2017; López & Peters, Citation2012; Sundgren & Svanström, Citation2014). Researchers also show that growth in a local office and concentrated client deadlines temporarily stress the resources of audit offices, resulting in lower audit quality (Bills et al., Citation2016; Czerney et al., Citation2019). Overall, this evidence shows that limited attention due to increased workload can constrain the resources of audit offices and lower audit quality.

We rely on this framework and argue that when an audit office has clients requiring more attention and resources, their ability to audit the rest of their clients effectively is reduced. Therefore, we focus on a subset of clients within the same audit office that distracts the audit offices and increases time pressures. Specifically, we argue that distressed clients require more attention and greater professional skepticism from the audit offices that constitute a potential subset of clients that can temporarily stress the resources of the audit office. This argument is supported by the literature on corporate financial distress which has demonstrated that during times of financial difficulties, managers engage in dishonest financial reporting to avoid violating debt covenants or to maximise their short-term compensation (Efendi et al., Citation2007; Sweeney, Citation1994).

Since financially distressed clients are more likely to use complex earnings management methods, auditors must exercise a greater degree of professional skepticism and audit effort to ensure effective audits and reduce their risks to tolerable levels (Beasley et al., Citation2010; Brazel et al., Citation2016).Footnote2 However, an audit office generally reserves an economically optimal level of resources for the audits of their portfolio of clients. Accordingly, an audit office risks its resources being spread too thinly and their staff being distracted when it must pay more attention to the audits of distressed clients at the expense of the less risky, non-distressed clients. Therefore, it is plausible to expect that non-distressed clients will be more exposed to reduced effort by audit offices and have lower quality earnings.

We build our framework for auditor distraction at the audit office-level. It is plausible that distraction caused by distressed clients is more visible at the audit-team level. However, we argue that the audit office is primarily responsible for allocating resources, dealing with clients, and monitoring audit teams’ activities to ensure the timely fulfilment of their project objectives (Czerney et al., Citation2019; Francis, Stokes, et al., Citation1999). The audit office could also reassess the situation and allocate more resources to audit teams in an effort to reduce the negative implications of auditor distraction. With the lack of data availability at the audit-team level, the audit office serves as a reliable unit of analysis.

2.3. Auditor distraction and audit effort

We focus on two important aspects of audit effort concerning auditor distraction – audit delay and audit fees. Audit delay or audit report lag is the length of time between the firm’s fiscal year-end and the completion of its audit report and plays a vital role in determining the timeliness of annual reports (Givoly & Palmon, Citation1982). Studies show that the timeliness of financial reporting is associated with accurate valuations (Bamber et al., Citation1993; Givoly & Palmon, Citation1982). Timeliness, in general, improves the usefulness of reported financial statements for decision-making, while a delay could trigger information uncertainty related to decisions based on financial statements.

Evidence from previous research suggests that financial reporting is a technical process that thus requires continuous effective information exchange between the client and the auditor (Beasley et al., Citation2009). To deliver timely and accurate financial statements, review the contents of the financial statements and the audit process, and determine the effectiveness of internal control, the audit committee of the client firm regularly meets with the auditor. A distracted auditor would potentially be unable to allocate sufficient time and resources to actively engage with the client’s audit committee and management. This lack of communication between the client and the auditor and excessive time pressure may impede information processing and curb coordination, thus preventing the client from delivering timely financial statements. We, therefore, express our first hypothesis as follows:

H1: Auditor distraction increases an audit office’s workload and is positively associated with audit report delay.

H2: Auditor distraction decreases an audit office’s bargaining power and is negatively associated with audit fees.

2.4. Auditor distraction and earnings quality

An audit office’s distraction can impede the clients’ earnings quality through several different channels. First, given that audit quality is the joint probability that an auditor detects and reports a material misstatement (DeAngelo, Citation1981), this probability will likely decrease as auditors pay less attention when distracted. It may be further reduced if doing so significantly increases the audit office’s workload. For example, a distracted audit office under time constraints may also avoid modification of the standard audit report, as that process often requires time-consuming discussions with the client firm’s management, the audit firm’s in-house counsel, or the quality review partner. Similarly, audit offices may increase instances of signing off on a step in the audit program without fully completing all the required audit tasks.

Srinidhi and Gul (Citation2007) argue that curbing earnings management is critical to audit quality. An auditor that charges higher audit fees presumably exerts more effort to gather audit evidence that allows the auditor to evaluate the errors in accruals estimations. After identifying inconsistencies or factors affecting the true and fair view of the financial statements, the auditor requires managers to correct their estimates, modify their accounting methods, and increase the quality of the accruals. Consistent with these arguments, Hoitash et al. (Citation2007) find a negative association between audit fees and abnormal accruals. In a similar study, Caramanis and Lennox (Citation2008) use audit hours to measure audit effort and find that audit effort is negatively related to discretionary accruals. While auditors may not directly express their opinion about real earnings management, Commerford et al. (Citation2016) provide interview evidence indicating that auditors are aware of managers’ use of real earnings management and try to mitigate their discomfort by increasing skepticism and changing audit procedures and risk assessments of their audits. A distracted audit office, which lacks time and resources, may simply overlook earnings management activities that would normally require additional effort.

Second, auditors play a crucial role in financial reporting by providing an independent and objective assessment of a client’s financial statements. This process often involves professional skepticism, where the auditors approach their work with a critical mindset by using their professional knowledge, skills, and abilities to gather and objectively evaluate evidence, neither assuming management’s dishonesty nor unquestioned honesty (Nelson, Citation2009). However, to the extent that distraction is observable, client firms may expect the lower intensity of professional skepticism from a distracted auditor. In such instances of lower external monitoring, managers may manipulate earnings to maximise their own and/or their shareholders’ wealth. Since managers are more likely to overstate earnings than understate them and given that auditors are generally more concerned about income-increasing earnings management (Becker et al., Citation1998; Nelson et al., Citation2002), we primarily focus on the association between distraction and income-increasing earnings management. Since managers use both accruals and real activities to manipulate earnings (see e.g. Ali & Zhang, Citation2015), we state our third hypothesis as follows:

H3: Auditor distraction is positively associated with income-increasing accrual and real earnings manipulations.

H4: Auditor distraction is negatively associated with the magnitude of stock price reaction to earnings announcements.

3. Data and research methodology

3.1. Measuring auditor distraction

In Section 2, we predict that clients’ financial wellbeing is critical to determining the workload of an audit office and the extent to which audit offices are distracted. To identify firms in financial distress, we rely on the KZ index. The literature in economics and finance has extensively used this index as a measure of financial constraint (e.g. Almeida et al., Citation2004; Baker et al., Citation2003; Bakke & Whited, Citation2010; Lamont et al., Citation2001). Specifically, for each Compustat firm-year, we follow Baker et al. (Citation2003) and estimate the KZ index with Equation (1).

(1)

(1) where CFit is cash flow; DIVit is cash dividends; Cit is cash balances; LEV is the sum of long-term and short-term debt divided by assets; Q is the market value of equity plus assets minus the book value of equity all divided by assets; and Ait-1 is the lagged assets. The subscripts i and t denote the firm and year, respectively.

After creating this index, we divide firms into annual quintiles based on the KZ index. We next retain only the top quintile of each year and merge these data with Audit Analytics. Then, we measure Distraction at the audit office level as the percentage of audit fees of an office stemming from financially distressed clients.Footnote3 Our measure of Distraction has a continuous distribution; a higher (lower) value signifies that the audit office is more (less) distracted. The extent to which a client’s audit office is distracted depends on the proportion of audit fees obtained from distressed clients. Therefore, our measure of distraction is exogenous to healthier clients of an audit office because neither these clients nor the office are likely to affect the financial position of distressed clients.Footnote4 Further, distressed firms must either overcome their financial problems or file for bankruptcy. In either case, our measure of distraction changes, introducing meaningful variation throughout the sample period.Footnote5

3.2. Measuring audit effort and clients’ earnings quality

We follow the prior literature (Zhang, Citation2018) and use audit delay and audit fees as our two main measures of audit effort. We define audit delay as the natural logarithm of the difference between the completion date of the client’s audit report and its fiscal year-end date, and we define audit fees as the natural logarithm of audit fees based on information obtained from Audit Analytics. To capture earnings quality, we rely on two measures of discretionary accruals (accruals earnings management) and one measure of abnormal discretionary expenses (real earnings management). Specifically, we estimate the Jones (Citation1991) model as modified by Dechow et al. (Citation1995) and the Dechow and Dichev (Citation2002) model as modified by McNichols (Citation2002). Similarly, to capture real earnings management, we follow Ali and Zhang (Citation2015) and use the discretionary expenses model introduced by Roychowdhury (Citation2006).Footnote6 Empirically, we estimate Equations. (2)-(4) for each industry and year separately and obtain the residual terms.Footnote7 Since we focus on income-increasing earnings management, we use signed residuals instead of using the absolute values.

(2)

(2) where TACC is the total accruals calculated as the difference between income before extraordinary items and operating cash flows; AT is total assets; ΔREV is the change in revenue; ΔAR is the change in accounts receivable; and PPE is gross property, plant, and equipment.

(3)

(3) where ΔWC is the change in working capital (measured as current assets less cash and cash equivalents minus current liabilities plus debt in current liabilities); and CFO is cash flows from operations. All other variables are as defined previously.

(4)

(4) where DISEXP is the discretionary expenses that is defined as the sum of R&D, advertising, and selling, and general and administrative expenses. If data for selling and general and administrative expenses are available, and data for R&D and advertising expenses are missing, then we set these two expenses to zero. All other variables are as defined previously.

3.3. Sample selection

We base our empirical analysis on a sample of publicly listed firms in the US from 2000 to 2019. We obtain accounting data from Compustat, stock data from the Centre for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), and audit data from Audit Analytics. Our sample selection criteria are as follows. First, we consider all publicly listed firms in the US from 2000 to 2019 and remove firm-year observations with missing audit fees or unknown auditor information. Second, we exclude firm-year observations where audit offices are located outside the US, have less than three clients, or have only one office across the country in the given year. Third, we omit observations with missing accounting data to calculate our measure of audit office distraction and other necessary dependent and control variables. Finally, we exclude firms in the utilities (SIC codes 4900–4999) and financial (SIC codes 6000–6999) industries because these industries tend to be regulated. Our final sample size for the main tests comprises 42,470 firm-year observations.

3.4. Regression model

After calculating the distraction measure, we merge these data with Compustat and Audit Analytics to get a firm-year sample. We delete all financially distressed firms in the fifth quintile of the KZ index. To test the association between distraction and audit effort (hypothesis 1 and 2), we use the following regression equation:

(5)

(5) where the natural logarithm of Audit Delay or Audit Fee is the dependent variable and Distraction is the main independent variable. The control variables are adopted from the prior literature (e.g. Choi et al., Citation2010; Zhang, Citation2018) and are client size (Firm Size), book-to-market ratio (Book to Market), the number of business segments (Segments), financial leverage (Leverage), sales growth rate (Sales Growth), profitability (Return on Assets), loss or profit (Loss), sales volatility (Std. Sales), cash flow volatility (Std. CFO), ratio of inventory plus receivables to total assets (InvRec), square root of number of employees (Sqrt. Employees), and financing need (New Financing) as well as indicator variables for whether the client reports extraordinary items (Extraordinary Items), pays any foreign income tax (Foreign Operations), and receives a going concern opinion (Going Concern) or not. We also add several audit office controls, such as its size (Office Size) and industry specialisation (Industry Specialist) as well as indicators for whether the audit firm is an industry leader (Industry Leader) and whether the client is audited during the busy audit season (Busy Season) or not. Appendix A provides more detailed definitions of all variables. Following Cameran et al. (Citation2022), we add audit firm fixed effects to control for unobservable and time-invariant audit office characteristics.Footnote8 We also add industry (two-digit SIC code) and year fixed effects and report the heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the client level.Footnote9 Based on hypotheses 1 and 2, we predict a positive (negative) association between distraction and audit delay (audit fees).

To test the relationship between distraction and income-increasing earnings management (hypothesis 3), we follow Francis, Maydew, et al. (Citation1999) and Choi et al. (Citation2010) and estimate the following regression equation:

(6)

(6) where Earnings Management is the signed residuals from Equation (2), (3), or (4) that is denoted as Abnormal Accruals MJ, Abnormal Accruals DD, and Abnormal Disc. Expenses, respectively. We add the same set of control variables (Controls) and fixed effects as in Equation (5). Based on hypothesis 3, we predict a positive (negative) and statistically significant relationship between distraction and income-increasing accruals (real) earnings management.

Finally, to test the association between distraction and the magnitude of the stock price’s reaction to earnings, we follow Hackenbrack and Hogan (Citation2002) and estimate the following regression equation:

(7)

(7) where CAR is the cumulative abnormal return for days −1 and 0, where 0 is the earnings announcement date; Surprise is the unexpected earnings; and Distracted Year is an indicator variable that equals 1 if the audit office receives at least 10 percent of its fees from distressed clients in that year, and 0 otherwise. We add the same set of control variables (Controls) and fixed effects as in Equation (5).Footnote10 We predict that the interaction term between Distracted Year and Surprise will be negative and statistically significant (hypothesis 4).

3.5. Entropy balancing

To ensure that our results are not driven by endogenous matching between firms with observable characteristics that contribute towards lower audit effort and clients’ earnings quality and a distracted audit office, we use a multivariate matching technique named entropy balancing developed by Hainmueller (Citation2012). Several recent studies have utilised the matching technique to address endogeneity concerns (see e.g. Chahine et al., Citation2020; Chapman et al., Citation2019; McMullin & Schonberger, Citation2020). Entropy balancing uses a weighting scheme such that post-weighting, the distribution of each matching variable is virtually identical between the control and treatment samples. To implement this, we use the dichotomous Distracted Year and require an entropy-balanced sample across the first two moments (mean and variance) for each control variable specified in Equation (5).Footnote11

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis

presents our final sample’s cross-sectional descriptive statistics and mean differences based on Distracted Year. The table shows that the mean (median) of Distraction is 0.120 (0.084) and indicates that audit offices of the sample firms obtain, on average, 12.0 percent of their total audit fees from financially distressed clients. The mean (median) of audit delay is 4.087 (4.111), or approximately 60 (61) calendar days. The mean (median) of the natural logarithm of audit fees is 13.545 (13.566), which translates to approximately $762,990 ($779,182). These numbers are similar to those in other studies (e.g. Zhang, Citation2018). The mean differences indicate that audit offices issue reports with a delay during the distracted years and receive lower fees. Similarly, the descriptive statistics for accruals and real earnings management indicate that on average, clients manage their earnings upwards through accruals and real activities. The difference between distracted and non-distracted years is statistically significant and positive for accruals earnings management and negative and statistically significant for real activities manipulation. These results are consistent with our hypotheses and provide some empirical backing to our theoretical arguments. The descriptive statistics for other variables are similar to other studies (e.g. Choi et al., Citation2010; Zhang, Citation2018).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis.

4.2. Multivariate analysis

provides the results of the OLS regressions for the pooled and entropy-balanced samples. In column (1), when the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of audit delay, the coefficient for Distraction is positive and statistically significant at the 5 percent level [β = 0.032**, t-statistic = 2.34]. In column (2), our dependent variable is the natural logarithm of audit fees, and the coefficient for Distraction is negative and statistically significant at the 1 percent level [β = −0.103***, t-statistic = −3.49]. The results are similar when we use the entropy-balanced sample. In columns (3) and (4), the coefficient for Distracted Year is positive and negative, respectively. These results are consistent with the idea that when audit offices are distracted, they face greater time pressure and delay their audit reports. Similarly, because the client has more bargaining power given the excessive workload of the audit office, it also charges a lower fee to the client.

Table 2. Auditor distraction and audit effort.

The coefficients for control variables are largely consistent with the literature. For instance, Firm Size and Profitability are associated with shorter audit delays, while Book to Market, Segments, Leverage, Loss, Foreign Operations, Going Concern, Busy Season, and Office Size are associated with larger delays. Larger clients with greater profitability will likely pay higher fees to accelerate the audit process and to avoid delays. Similarly, clients with fewer growth opportunities, many segments, more leverage, and foreign operations; and clients with losses and that are a going concern have longer audit delays. Large audit offices take longer to issue audit reports, particularly when the client’s fiscal year ends in December. In contrast, Firm Size, Segments, Leverage, Loss, Sqrt. Employees, Extraordinary Items, Foreign Operations, Going Concern, Busy Season, Industry Specialist, and Office Size are positively associated with audit fees. This effect is likely because large firms with several segments and many employees, higher debt, foreign operations, and extraordinary items pay larger audit fees due to more hours required to manage the workload. Industry specialists and large offices charge a fee premium, particularly when auditing clients during a busy season.

presents the regression results from testing the relationship between an audit office’s distraction and earnings quality. In columns (1) and (2), we use signed abnormal accruals obtained from estimating Equations. (2) and (3). The coefficient for Distraction is positive and statistically significant. This result indicates that clients increasingly use accruals to manage earnings upwards as the distraction increases. Similarly, in column (3), the negative and statistically significant sign on Distraction indicates that clients use real activities to reduce costs and manage earnings upwards. These results are consistent with our expectations in hypothesis 3. The results obtained from an entropy-balanced sample in columns (4)–(6) are qualitatively similar. Overall, this evidence shows that when the auditors in an audit office are distracted, the earnings quality of their clients decreases.

Table 3. Auditor distraction and clients’ earnings quality.

The results in and are also economically significant. When audit offices are distracted, ceteris paribus, they take 3.3 percent (or two calendar days) more time to issue an audit report than in the previous year. Similarly, when audit offices are distracted, they receive 1.5 percent lower audit fees than in the prior year.Footnote12 In , the coefficients indicate that on average, firms manage their earnings upwards by approximately 0.3 and 0.2 percent of total assets during distracted years. Similarly, they decrease discretionary expenses by about 0.6percent of total assets compared to non-distracted years.

We next test whether the market perceives the earnings quality of distracted audit offices’ clients as less informative and reacts less intensely to earnings surprises (hypothesis 4). Specifically, we estimate Equation (7) for our full sample. The results reported in show that the cumulative abnormal returns around the earnings announcement date are positively and statistically significant for the magnitude of unexpected (surprise) earnings. The interaction term between Distracted Year and Surprise is negative and statistically significant. This result indicates that when the audit office is distracted, clients’ earnings quality declines, and earnings become less informative, leading to a lower market response. The results are similar if we calculate CAR using factor-adjusted returns. These empirical findings support our theorising and indicate that distracted audit offices affect the earnings quality of their clients.Footnote13

Table 4. Auditor distraction and market response to unexpected earnings.

4.3. Additional analyses

4.3.1. Alternative measures of audit delay and audit fees

We test whether our results are robust to alternative measures of audit effort. First, we follow Hoitash and Hoitash (Citation2018) and redefine our audit delay measure to consider the SEC’s rule change in 2006 which stipulated new deadlines for audit reports based on clients’ public float.Footnote14 Therefore, we define an alternative measure of audit delay as the number of days between the fiscal year-end date and the audit report date minus the SEC’s filing deadline requirement (60, 75, and 90 days for large accelerated, accelerated, and non-accelerated, respectively). Similarly, we alternatively measure audit fees as the natural logarithm of inflation-adjusted fees and express the fees in constant 2000 dollars. shows that using these alternative measures does not change our inferences. We continue to find a positive (negative) and statistically significant coefficient for Distraction when we use audit delay (audit fee) as our dependent variable. These results further mitigate concerns that our results are driven by measurement error.Footnote15

Table 5. Auditor distraction and audit effort: Alternative measures of audit delay and audit fees.

4.3.2. Auditor distraction and future audit effort

We argue that auditor distraction is a temporary phenomenon, and once the audit office can reallocate resources, its effects should largely disappear. Consequently, in the years after the distraction, we would expect no differences in audit delay and audit fees. We formally test this expectation and report the results in . Except for the one-year-ahead audit delay, we find that the coefficients for Distraction in all other specifications are statistically insignificant. This result supports the idea that distraction is temporary, and once the audit office can allocate resources more optimally, it can issue the reports on time and have more bargaining power in setting audit fees.

Table 6. Auditor distraction and future audit effort and audit fees.

4.3.3. Alternative measure of auditor distraction

Subsection 3.1 defines the audit office’s distraction as the proportion of audit fees derived from distressed clients. To define distressed clients, we rely on the KZ index. To illustrate that our results are robust to alternative measures of financial distress, we recreate our measure of distraction using Altman’s (Citation1968) Z-score index. We define financially distressed clients as those with a score below 1.81 and measure distraction at the office level. The results in indicate that our findings remain robust to using this alternative measure of distraction. We find that distraction is positively associated with audit delay and income-increasing earnings management and negatively related to audit fees. These findings further support our hypotheses and reduce any concerns for measurement error.

Table 7. Auditor distraction, audit effort, and earnings quality: Alternative measure of distraction.

4.3.4. Placebo test

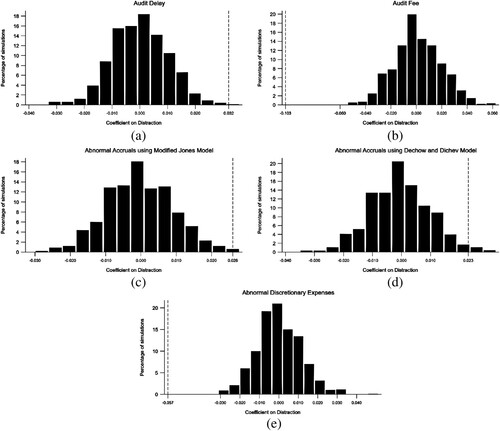

We estimate a placebo test to reduce concerns related to randomness and mechanical bias in the data. illustrates the results of the placebo test that randomly assigns Distraction to a year. We repeat this random assignment 1,000 times and estimate our models in Equations. (5) and (6) for each sample. The distribution of the estimated coefficients for Distraction from these regressions, reported in , shows that the estimated coefficients are significantly different from the dotted line that represents the true coefficient estimates from and . Furthermore, only a handful of these estimated coefficients are statistically significant at the conventional levels. These findings indicate that our results are unlikely to be driven by mechanical bias or randomness in the data. In , we also provide the mean coefficients from each placebo test and test whether the mean is statistically different than zero. The p-values associated with the t-tests indicate that only the mean coefficient in b is statistically different than zero at the 10 percent level. However, the mean coefficient in b is positive and the corresponding actual coefficient in is negative, indicating that there is no systematic bias. These results further strengthen our confidence in the robustness of our findings and support the validity of the estimated coefficients presented in and .

Figure 1. Auditor distraction, audit effort, and clients’ earnings quality: Placebo test.

Notes: This figure illustrates the results of a placebo test that randomly assigns Distraction. This procedure is repeated 1,000 times and the distribution of the estimated coefficients for Distraction from the regressions are reported. The dotted line represents the true coefficient estimates from Tables 2 and 3. Distraction is the ratio of an audit office’s audit fees stemming from financially distressed clients to total audit fees the office obtains in the given year. See subsection 3.1 for more details. ln (Audit Delay) is the natural logarithm of the difference between the completion date of the client’s audit report and the fiscal year-end date. ln (Audit Fee) is the natural logarithm of audit fees. Appendix A has the definitions of all other variables.

4.3.5. The effects of office size, industry specialisation, and auditor tenure

We examine the moderating effects of audit office size, industry specialisation, and auditor tenure on the negative effects of distraction on audit effort. Consistent with the prior evidence on audit office size, we argue that large audit offices have more resources and may be less prone to the negative implications of distraction.Footnote16 The results in columns (1) and (2) of show that the audit office size only mitigates the negative implications of distraction on audit fees. This finding is likely because large audit offices may have more bargaining power than smaller ones. Similarly, we expect industry specialization to reduce the negative effects of the audit office’s distraction. The results in columns (3) and (4) indicate that the audit office’s industry specialisation only helps reduce audit delay but does not help the audit office charge higher audit fees. Finally, we predict that an auditor with more experience with the client (captured by auditor tenure) will have the necessary expertise to generate a timelier audit report and may also have a better client-auditor relationship that enables the audit office to have more bargaining power. The results in columns (5) and (6) are consistent with these arguments. The auditor’s tenure reduces the negative implications of distraction on audit report delay and audit fees. These findings provide further insights into how the characteristics of audit offices influence the relationship between distraction and audit effort.Footnote17

Table 8. Auditor distraction and audit effort: The effects of office size, industry specialisation, and audit firm tenure

5. Conclusion

In this study, we examine how auditor distraction resulting from limited attention and time pressures influences audit effort and clients’ earnings quality. Specifically, we argue that financially distressed clients constitute a potential group that can temporarily stress the resources of an audit office, leading to longer audit delays and reduced audit effort on the audits of non-distressed clients that can affect their earnings quality. We find evidence consistent with our predictions using a sample of publicly listed US firms over the period from 2000 to 2019. Our results show that distracted audit offices have longer audit delays and lower fees for their audits and their non-distressed clients have a higher likelihood of engaging in income-increasing earnings management. Moreover, we find that distraction lowers the non-distressed clients’ earnings response coefficient. Our findings suggest that distraction is temporary and that the audit office eventually regains focus in one to two years.

Our results have important implications for the auditing literature, audit offices, and audit oversight bodies. First, our study extends the literature on how audit office characteristics influence the clients’ reporting environment by highlighting the role of audit offices’ distraction. This distraction can lead to longer delays and reduced audit effort by auditors and reduced earnings quality in clients, negatively affecting the reliability and credibility of financial reporting. Second, audit offices may use our findings as motivation to enhance their existing quality improvement initiatives, particularly in reallocating audit resources when encountering newly distressed clients. Third, audit oversight bodies may consider our findings in managing their existing audit inspection criteria. Regulators may also implement policies encouraging audit offices to manage their resources effectively and to prioritise allocating attention to financially distressed and non-distressed clients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Editor-in-Chief (Charles H. Cho), Associate Editor (Mara Cameran) and two anonymous referees for their constructive feedback throughout the review process. We gratefully acknowledge comments received from the participants of the Nordic Accounting Conference 2021, 44th Annual Congress of the European Accounting Association (EAA), and research seminar at Hanken School of Economics. We would also like to thank Gonul Colak, Henry Jarva, Jukka Kettunen, Yaping Mao, Ulf Mohrmann (discussant), and Dennis Sundvik for their valuable insights on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In , we also use the Altman’s (Citation1968) Z-score and use 1.81 as the cut-off point to measure financial distress. Using this measure does not alter our main inferences.

2 Consistent with this evidence, Gaeremynck et al. (Citation2008) study a sample of distressed Belgian firms and find that audit firms with clients that have weaker financial positions supply higher quality audits to manage their overall audit risk.

3 Our results are robust if we use clients’ total assets instead of audit fees.

4 One concern might be that our measure of distraction is similar to the “contagion effect” documented in Francis and Michas (Citation2013). However, the “contagion effect” speaks to the inherent systematic audit-quality problems of the audit office that persists over long periods of time. We make no such assumptions in our setting. An audit office, regardless of its inherent audit-quality problems, may become distracted at any point if a significant number of its clients are financially distressed. To further address this issue with inherent office quality, we exclude all audit offices for which at least 10 percent of all clients report a materially adverse restatement in the current or prior two years. Our sample size drops slightly but our main inferences remain unchanged after excluding these cases. These exclusions mitigate the concern that systematic differences in audit-quality at the office level are driving our results.

5 Another concern related to our measure of distraction may be that we are measuring a form of overall portfolio risk. To mitigate this concern, we define Portfolio Risk similarly as in Francis and Michas (Citation2013). The correlation between our measure of distraction and Portfolio Risk is 0.207. We also repeat our analysis using Portfolio Risk as our main measure instead of distraction and find no evidence that it affects audit delay, audit fees, or the clients’ earnings quality in the same way as distraction. Additionally, we repeat our analysis using Portfolio Risk as an additional control variable. Its inclusion does not affect our main inferences. We, therefore, conclude that the two measures are significantly different and capture different aspects of audit office characteristics. These results are available on request.

6 Prior literature extensively employs earnings restatements as a measure of earnings quality. We test whether clients of distracted auditors are more likely to restate their earnings and find some evidence of a higher likelihood of earnings restatement. However, these results are not robust to the inclusion of audit firm fixed effects. These findings may suggest that while clients engage in income-increasing earnings management, they are less likely to materially inflate their earnings that could lead to an accounting restatement.

7 Following common practice in the literature, we require at least 10 observations in a given industry and year and winsorize all the inputs of the model at the 1st and 99th percentile.

8 Cameran et al. (Citation2022) also find that audit office fixed effects have an incremental effect on audit quality. However, our results are not robust to the inclusion of audit office or client fixed effects.

9 Our results are robust to clustering standard errors at the audit firm level and audit office level. However, since client-level clustering produces the most conservative t-statistics, we tabulate our results using clustering at the client level.

10 Interacting the control variables with Surprise produces similar results. For brevity, we report the results without the additional interactions. These results are available on request.

11 Untabulated results indicate that after implementing entropy balancing, there are no statistically significant differences between distraction and non-distraction years.

12 We derive these economic significances by comparing all client-years when the audit office is distracted (at least 10 percent of audit fees derived from distressed clients) with one-year prior to distraction. Our sample size shrinks, but we are able to derive meaningful insights.

13 Based on the estimates in column (4) and summary statistics in , keeping all else equal, when a firm has a Surprise of 0.016 relative to the stock price in the previous year, clients of distracted audit offices (Distracted Year = 1) have a CAR of approximately 1.984 [2.028–0.041 + (0.693 × 0.016) – (0.864 × 0.016)] and clients of non-distracted audit offices (Distracted Year = 0) have a CAR of approximately 2.039 [2.028 + 0.693(0.016)]. These CARs indicate an absolute difference of 5.5 basis points [2.039–1.984] or a relative decrease of around 2.69 percent [(2.039–1.984) / 2.039 × 100] for clients of distracted audit offices. These findings highlight the economically significant effect of distracted audit offices on the earnings response coefficient.

14 We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

15 Lambert et al. (Citation2017) find that the SEC’s rule change affected audit delays and increased the time pressures on audit offices in the initial year of compliance. We use the 2006 rule change to test whether the effect of distraction on delays is stronger prior to the rule change. We find consistent evidence of a stronger effect. The coefficient for Distraction is economically and statistically more significant before 2006 than in the period after 2006. This significance indicates that the SEC’s rule change may have limited audit offices in how much time they could take to issue audit reports.

16 Alternatively, we also consider the effects of Big4 and non-Big4 audit offices on the negative association between audit offices’ distraction and audit effort and earnings quality. While we find that non-Big4 clients are more exposed to the effects of distraction, we find no evidence to suggest that our results are driven by non-Big4 clients.

17 In untabulated results, we find no consistent evidence to suggest that these variables mitigate the positive association between audit offices’ distraction and income-increasing earnings management. Furthermore, we also do not find any differences in our results among distressed and non-distressed firms. This is likely because we have already excluded the highly distressed clients (top quintile of the KZ-index) from our sample. The remaining sample is largely non-distressed, so we do not expect any statistically significant differences between the remaining firms based on the level of distress.

References

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., Peters, G. F., & Raghunandan, K. (2003). An empirical investigation of audit fees, nonaudit fees, and audit committees. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1506/8YP9-P27G-5NW5-DJKK

- Alderman, C. W., & Deitrick, J. W. (1982). Auditor’s perceptions of time budget pressures and premature sign-offs: A replication and extension. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 1(2), 54–68.

- Ali, A., & Zhang, W. (2015). CEO tenure and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 59(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.11.004

- Almeida, H., Campello, M., & Weisbach, M. S. (2004). The cash flow sensitivity of cash. Journal of Finance, 59(4), 1777–1804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00679.x

- Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis, and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1968.tb00843.x

- Asare, S. K., Trompeter, G. M., & Wright, A. M. (2000). The effect of accountability and time budgets on auditors’ testing strategies. Contemporary Accounting Research, 17(4), 539–560. https://doi.org/10.1506/F1EG-9EJG-DJ0B-JD32

- Baker, M., Stein, J. C., & Wurgler, J. (2003). When does the market matter? Stock prices and the investment of equity-dependent firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 969–1005. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360698478

- Bakke, T. E., & Whited, T. M. (2010). Which firms follow the market? An analysis of corporate investment decisions. Review of Financial Studies, 23(5), 1941–1980. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp115

- Bamber, E. M., Bamber, L. S., & Schoderbek, M. P. (1993). Audit structure and other determinants of audit report lag: An empirical analysis. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 12(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Barton, J. (2005). Who cares about auditor reputation? Contemporary Accounting Research, 22(3), 549–586. https://doi.org/10.1506/C27U-23K8-E1VL-20R0

- Beasley, M. S., Carcello, J. V., Hermanson, D. R., & Neal, T. L. (2009). The audit committee oversight process. Contemporary Accounting Research, 26(1), 65–122. https://doi.org/10.1506/car.26.1.3

- Beasley, M. S., Hermanson, D. R., Carcello, J. V., & Neal, T. L. (2010). Fraudulent financial reporting, 1998-2007: An analysis of U.S. public companies. Association Sections, Divisions, Boards, Teams. 453. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_assoc/453.

- Beck, M. J., Gunn, J. L., & Hallman, N. (2019). The geographic decentralization of audit firms and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 68(1), 101234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2019.101234

- Becker, C. L., Defond, M. L., Jiambalvo, J., & Subramanyam, K. R. (1998). The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 15(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1998.tb00547.x

- Bills, K. L., Swanquist, Q. T., & Whited, R. L. (2016). Growing pains: Audit quality and office growth. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(1), 288–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12122

- Braun, R. L. (2000). The effect of time pressure on auditor attention to qualitative aspects of misstatements indicative of potential fraudulent financial reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-3682(99)00044-6

- Brazel, J. F., Jackson, S. B., Schaefer, T. J., & Stewart, B. W. (2016). The outcome effect and professional skepticism. The Accounting Review, 91(6), 1577–1599. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51448

- Cameran, M., Campa, D., & Francis, J. R. (2022). The relative importance of auditor characteristics versus client factors in explaining audit quality. Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 37(4), 751–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X20953059

- Caramanis, C., & Lennox, C. (2008). Audit effort and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 45(1), 116–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.05.002

- Casterella, J. R., Francis, J. R., Lewis, B. L., & Walker, P. L. (2004). Auditor industry specialization, client bargaining power, and audit pricing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 23(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2004.23.1.123

- Chahine, S., Colak, G., Hasan, I., & Mazboudi, M. (2020). Investor relations and IPO performance. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(2), 474–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-09526-8

- Chapman, K., Miller, G. S., & White, H. D. (2019). Investor relations and information assimilation. The Accounting Review, 94(2), 105–131. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52200

- Cherry, E. C. (1953). Some experiments on the recognition of speech, with one and with two ears. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 25(5), 975–979. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1907229

- Choi, J.-H. H., Kim, J. B., & Zang, Y. (2010). Do abnormally high audit fees impair audit quality? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 29(2), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2010.29.2.115

- Collins, D. W., & Salatka, W. K. (1993). Noisy accounting earnings signals and earnings response coefficients: The case of foreign currency accounting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 10(1), 119–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1993.tb00385.x

- Commerford, B. P., Hermanson, D. R., Houston, R. W., & Peters, M. F. (2016). Real earnings management: A threat to auditor comfort? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 35(4), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-51405

- Czerney, K., Jang, D., & Omer, T. C. (2019). Client deadline concentration in audit offices and audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 38(4), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-52386

- DeAngelo, L. E. (1981). Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 3(3), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(81)90002-1

- Dechow, P. M., & Dichev, I. D. (2002). The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(s-1), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.61

- Dechow, P. M., Sloan, R., & Sweeney, A. P. (1995). Detecting earnings management. The Accounting Review, 70(2), 193–225.

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.002

- Efendi, J., Srivastava, A., & Swanson, E. P. (2007). Why do corporate managers misstate financial statements? The role of option compensation and other factors. Journal of Financial Economics, 85(3), 667–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.05.009

- Ettredge, M., Fuerherm, E. E., & Li, C. (2014). Fee pressure and audit quality. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 39(4), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.04.002

- Francis, J. R. (2011). A framework for understanding and researching audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 30(2), 125–152. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50006

- Francis, J. R., Maydew, E. L., & Sparks, H. C. (1999). The role of big 6 auditors in the credible reporting of accruals. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 18(2), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.1999.18.2.17

- Francis, J. R., & Michas, P. N. (2013). The contagion effect of low-quality audits. The Accounting Review, 88(2), 521–552. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50322

- Francis, J. R., Michas, P. N., & Yu, M. D. (2013). Office size of big 4 auditors and client restatements. Contemporary Accounting Research, 30(4), 1626–1661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12011

- Francis, J. R., Reichelt, K., & Wang, D. (2005). The pricing of national and city-specific reputations for industry expertise in the U.S. audit market. The Accounting Review, 80(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2005.80.1.113

- Francis, J. R., Stokes, D. J., & Anderson, D. (1999). City markets as a unit of analysis in audit research and the re-examination of big 6 market shares. Abacus, 35(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6281.00040

- Francis, J. R., & Yu, M. D. (2009). Big 4 office size and audit quality. The Accounting Review, 84(5), 1521–1552. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.5.1521

- Fung, S. Y. K., Gul, F. A., & Krishnan, J. (2012). City-level auditor industry specialization, economies of scale, and audit pricing. The Accounting Review, 87(4), 1281–1307. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10275

- Gaeremynck, A., Van Der Meulen, S., & Willekens, M. (2008). Audit-firm portfolio characteristics and client financial reporting quality. European Accounting Review, 17(2), 243–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180701705932

- Givoly, D., & Palmon, D. (1982). Timeliness of annual earnings announcements: Some empirical evidence. The Accounting Review, 57(3), 486–508.

- Goldman, N. C., Harris, M. K., & Omer, T. C. (2022). Does task-specific knowledge improve audit quality: Evidence from audits of income tax accounts. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 99, 101320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2021.101320

- Goodwin, J., & Wu, D. (2016). What is the relationship between audit partner busyness and audit quality? Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(1), 341–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12129

- Gul, F. A., Ma, S. M., & Lai, K. (2017). Busy auditors, partner-client tenure, and audit quality: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of International Accounting Research, 16(1), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.2308/jiar-51706

- Hackenbrack, K. E., & Hogan, C. E. (2002). Market response to earnings surprises conditional on reasons for an auditor change. Contemporary Accounting Research, 19(2), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1506/5XW7-9CY6-LLJY-BA2F

- Hainmueller, J. (2012). Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis, 20(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr025

- Hogan, C. E., & Jeter, D. C. (1999). Industry specialization by auditors. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 18(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.1999.18.1.1

- Hoitash, R., & Hoitash, U. (2018). Measuring accounting reporting complexity with XBRL. The Accounting Review, 93(1), 259–287. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51762

- Hoitash, R., Markelevich, A., & Barragato, C. A. (2007). Auditor fees and audit quality. Managerial Auditing Journal, 22(8), 761–786. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900710819634

- Hong Teoh, S., & Wong, T. J. (1993). Perceived auditor quality and the earnings response coefficient. The Accounting Review, 68(2), 346–366.

- Jones, J. J. (1991). Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research, 29(2), 193–228. doi:10.2307/2491047

- Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Prentice-Hall.

- Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(1), 169–213. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555163

- Lambert, T. A., Jones, K. L., Brazel, J. F., & Showalter, D. S. (2017). Audit time pressure and earnings quality: An examination of accelerated filings. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 58, 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2017.03.003

- Lamont, O., Polk, C., & Saá-Requejo, J. (2001). Financial constraints and stock returns. Review of Financial Studies, 14(2), 529–554. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/14.2.529

- Lee, G., Naiker, V., & Stewart, C. R. (2022). Audit office labor market proximity and audit quality. The Accounting Review, 97(2), 317–347. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2018-0496

- López, D. M., & Peters, G. F. (2012). The effect of workload compression on audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(4), 139–165. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10305

- McDaniel, L. S. (1990). The effects of time pressure and audit program structure on audit performance. Journal of Accounting Research, 28(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491150

- McMullin, J. L., & Schonberger, B. (2020). Entropy-balanced accruals. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(1), 84–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-019-09525-9

- McNichols, M. F. (2002). Discussion of the quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review, 77(SUPPL.), 61–69. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.61

- Minutti-Meza, M. (2013). Does auditor industry specialization improve audit quality? Journal of Accounting Research, 51(4), 779–817. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12017

- Moon, J. R., Shipman, J. E., Swanquist, Q. T., & Whited, R. L. (2019). Do clients get what they pay for? Evidence from auditor and engagement fee premiums. Contemporary Accounting Research, 36(2), 629–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12445

- Nelson, M. W. (2009). A model and literature review of professional skepticism in auditing. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 28(2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2009.28.2.1

- Nelson, M. W., Elliott, J. A., & Tarpley, R. L. (2002). Evidence from auditors about managers’ and auditors’ earnings management decisions. The Accounting Review, 77(SUPPL.), 175–202. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2002.77.s-1.175

- Otley, D. T., & Pierce, B. J. (1996). The operation of control systems in large audit firms. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 15(2), 65–84.

- Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). (2012). Maintaining and applying professional skepticism in audits. Staff audit practice alert No. 10 (SAPA 10). PCAOB.

- Roychowdhury, S. (2006). Earnings management through real activities manipulation. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(3), 335–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2006.01.002

- Simunic, D. A., & Stein, M. T. (1996). The impact of litigation risk on audit pricing: A review of the economics and the evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 15(Supplement), 119–134.

- Srinidhi, B. N., & Gul, F. A. (2007). The differential effects of auditors’ nonaudit and audit fees on accrual quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 24(2), 595–629. https://doi.org/10.1506/ARJ4-20P3-201K-3752

- Subramanyam, K. R. (1996). Uncertain precision and price reactions to information. The Accounting Review, 71(2), 207–219.

- Sundgren, S., & Svanström, T. (2014). Auditor-in-charge characteristics and going-concern reporting. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(2), 531–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12035

- Sweeney, A. P. (1994). Debt-covenant violations and managers’ accounting responses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17(3), 281–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(94)90030-2

- Whitworth, J. D., & Lambert, T. A. (2014). Office-level characteristics of the big 4 and audit report timeliness. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 33(3), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-50697

- Willett, C., & Page, M. J. (1996). A survey of time budget pressure and irregular auditing practices among newly qualified UK chartered accountants. British Accounting Review, 28(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1006/bare.1996.0009

- Zhang, J. H. (2018). Accounting comparability, audit effort, and audit outcomes. Contemporary Accounting Research, 35(1), 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12381