ABSTRACT

Academic second-chance education (SCE) provides young adults with the opportunity for upward mobility. However, many young people in academic SCE have unfavourable prerequisites, which make it difficult for them to meet academic requirements. In this article, we explore how teachers respond to this challenge in their practice and the extent to which teacher practice matches learner expectations. We look at formal academic SCE and the following aspects of teacher practice: supporting weak learners, applying rules on discipline and grading, and building teacher-learner relationships. Our basis is a dataset of 176 teachers and 600 learners in 9 schools of academic SCE in Germany. The results show that a majority of teachers report that they support weak learners and address learners’ personal needs whilst insisting on general rules for discipline and grading. However, almost half of the learners want more recognition of their adult status – more that is than their teachers perceive – by being granted autonomy, professional relational distance and more flexibility on absence rules. This article discusses the extent to which structural features of academic SCE make it difficult to perceive the adult needs of learners and at the same time to pursue challenging learning goals.

1. Introduction

In this article, we focus on academic second-chance education (SCE), i.e. SCE leading to the eligibility to study (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice Citation2018, 174; level 4 in the European Qualification framework). In many countries, young adults who leave compulsory education without or with only a low qualification are given a ‘second-chance’ to enter formal education in order to obtain the eligibility to study (see for an overview Desjardin, Citation2017 (worldwide); Orr et al. Citation2017 (Europe)). In order to obtain this qualification, learners in this type of SCE have to acquire abstract and complex academic knowledge according to a defined curriculum in a given amount of time and must pass final exams in a number of subjects. Since the pressure on all young people to obtain the highest possible school-leaving qualification has increased in recent decades (OECD, Citation2015), the proportion of young people in formal SCE with learning problems, broken school careers and also with personal and family problems has grown steadily (Bellenberg et al. Citation2019 (Germany); Glorieux et al. Citation2011 (Belgium); Looker and Thiessen Citation2008 (Canada); Marcotte Citation2012 (Canada); Martins et al. Citation2020 (Portugal); Raymond Citation2008 (Canada); Ross and Gray Citation2015 (Australia)).

We assume that academic requirements on the one hand and students who are not adequately prepared to fulfil them, on the other hand, can be seen as a central characteristic in formal academic SCE. A further characteristic is associated with the fact that the type of knowledge to be acquired (abstract and complex knowledge) and its organization (a defined curriculum, grading, exams) is structurally associated with an asymmetry between those who teach and those who learn (Pratt Citation1988). However, academic SCE is aimed at adults, who may have a strong desire to be treated by their teachers as self-directed and autonomous learners (Knowles Citation1970) rather than as students. These characteristics are thus associated with challenges that can be assumed to characterize SCE in countries where it is formally organized and intended to provide access to higher education. In this article, we are interested in how teachers respond to the challenges associated with this framework, using Germany as our example.

1.1. Academic SCE in Germany

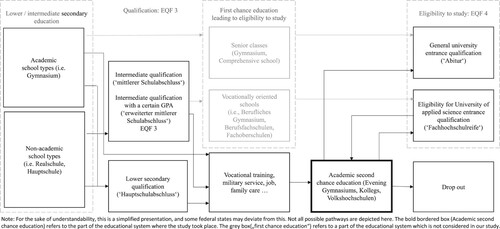

In Germany, formal academic SCE is either organized at a separate school type (for instance at Weiterbildungskollegs in North Rhine-Westphalia, where the study took place) or at adult education centres (Volkshochschulen as in Bavaria; see also ). These provide general educational programmes that aim at adults with a minimum age of 18 who have completed a course of vocational training and/or taken up employment, served in the military or cared for a family for at least two years (Freitag Citation2012). In the 2020/2021 school year, 22,671 learners participated in formal academic SCE, and 1.9% of all eligibilities to study achieved in general education were obtained via SCE (Statistisches Bundesamt Citation2021).

Academic SCE has day programmes and evening programmes, and those who attend the former are eligible for financial assistance from the state. After three years of academic SCE, the eligibility to study at a university (‘Abitur’) is obtained. Although it is possible to leave SCE after two years with the eligibility to study at a university of applied sciences (‘Fachhochschulreife’), this is not the focus of SCE programmes, which parallel the general academic upper secondary education track (‘Gymnasium’, see ), the most demanding school type in the German school system (see ; Harney Citation2016; Harney, Koch, and Hochstätter Citation2007).

Education at the general academic track leads directly to the eligibility to study after 5 (or 6) years at the lower secondary level and 3 years at the upper secondary level (the number of years depends on the individual school and the federal state (Land)). Students in academic SCE are taught the same curriculumFootnote1 in basic and advanced achievement courses and have to take the same standardized exams as upper secondary students in the general academic track.

Although they are adults, they use the same books as the adolescent students at the general academic track, and the pedagogical methods of the teachers, most of whom trained to be teachers at the general academic track, are typically those employed by school teachers in general education and seldom consider approaches based on principles of autonomous and self-directed learning (Seitter Citation2009). Due to these similarities with the academic track regarding organization, curriculum and standardized exams, scholars refer to a ‘generalization of the student role’ in academic SCE (Asselmeyer Citation1996; Kade Citation2005; Seitter Citation2009), and the terms ‘school’ and ‘student’ are used in official documents (e.g. APO WbK 2022).

However, there are considerable differences regarding the student composition at these two school types. The selection of students for the Gymnasium is based on ability, academic performance and learning behaviour at primary school, while access to academic SCE depends neither on a certain grade average nor on the acquisition of a certain qualification in lower secondary education. As mentioned above, an increasing proportion of students in academic SCE do not have the necessary prerequisites to successfully participate in academic SCE (Bellenberg et al. Citation2019; Koch Citation2018), and as a result, in recent decades the target group of academic SCE has become ‘vulnerable adults’ (instead of ‘gifted adults’ that SCE targeted when it was introduced in the 1920s). SCE in Germany perceives these ‘vulnerable adults’ as in need of help in order to obtain a higher school qualification that can prevent exclusion from society (Koch Citation2018). For this reason, we speak in the following of ‘vulnerable’ students (see also Papaioannou and Gravani Citation2018 for Greece) and their ‘needs’ (see also Wärvik Citation2013 for Great Britain).

1.2. Research aim

Against this backdrop, it can be stated that the structural framework of academic SCE that we described above is particularly pronounced in Germany. To answer our general question about how teachers deal with the resulting challenges, we draw on the following assumptions: From a sociological point of view, teachers have to react to institutional demands (for instance, students are themselves responsible for meeting performance standards; see Parsons, Citation1959; Dreeben Citation1968). However, from a pedagogical point of view, they are at the same time confronted with personal needs of students (students expect individual help and support; see Helsper Citation2004; Citation2010; Wernet Citation2003). This general tension manifests itself in concrete contradictions of pedagogical action (ibid), which we here call ‘pedagogical contradictions’.Footnote2 Teachers vary in their strategies to deal with these contradictions, and these strategies are influenced by personal and school characteristics.

In this article, our aim is to make a valuable contribution to the literature on academic SCE regarding the following aspects: Firstly, within the general tension between institution and person, there are several specific contradictions that are consistently identified as defining features of modern schools. While there have been some studies exploring how teachers respond to institutional and individual demands, these are qualitative in nature, focus on the teachers’ experiences of conflict, and are often limited to a specific type of pedagogical contradiction (Ball Citation2003; Brookfield Citation2013; Lippke Citation2012; Papaioannou and Gravani Citation2018; Wärvik Citation2013). In this article, we present a quantitative application of Helsper’s systematic approach (Citation2004; Citation2010) and we examine the structure of strategies employed by teachers in dealing with various contradictions.

Secondly, we investigate what kind of teacher practice is more likely under the structural framework of academic SCE, namely the presence of academic requirements and an adult student body with many vulnerable learners. For instance, we are interested in whether teachers respond more to the vulnerable learner body or to the academic demands of SCE. So far, structural conditions and their impact on teacher practice have rarely been systematically described (see e.g. Brookfield Citation2013; Papaioannou & Gravani Citation2018; Wärvik Citation2013). Thirdly, since students vary in their needs and expectations, for instance concerning teacher support and care (Phillippo Citation2012), teachers cannot meet the needs of all their students – for instance, if they are more support-oriented, they may reject those students who want more self-directed learning. We investigate here whether the expectations of certain groups of learners are perhaps systematically rejected by a teacher practice that has been established under the structural framework of academic SCE. To our knowledge, such a quantitative analysis of the congruence or lack of congruence between teacher and different groups of adult student perspectives has hitherto not been undertaken.

2. Theoretical and empirical background

This section is organized as follows: We describe in more detail what pedagogical contradictions are and what possibilities teachers have in general to deal with them (2.1). We assume that pedagogical contradictions occur whenever education is formally organized to provide qualifications and learners have little control over the content, timing and examinations. As mentioned in the introduction, this holds true for formal academic SCE. Our theoretical assertions are thus of a general nature and we will support them with examples from the international literature on formal adult education. We then develop our research questions by explaining which teacher practices are more likely under a certain structural framework (2.2) and by describing that learner heterogeneity makes it impossible for a teacher’s chosen practice to meet the needs of all the learners (2.3).

2.1. Pedagogical contradictions and teacher practice

According to the classical sociology of education (Dreeben Citation1968; Parsons Citation1959), in modern societies it is generally expected in schools that students are treated equally and in their specific role as ‘students’ and not as the diffuse entity ‘persons’. This means that statements and interests of teachers should normally concern only prerequisites, characteristics and results of learning processes, and not – for instance – the private life of students. Learners must adhere to performance standards that apply to all of them, and they must fulfil the corresponding performance requirements autonomously. These demands apply in all schools, but most clearly in school types or tracks with an academic focus, where students themselves are expected to be responsible for their learning progress.

However, from a pedagogical point of view, these institutional expectations often fail to meet the individual needs and expectations of students (Helsper Citation2004; Citation2010; Wernet Citation2003). Students expect or demand to varying degrees – depending on their personal prerequisites – that their teachers take into account their personal situation, and treat them not only in their role as students. This results in contradictory demands from persons (in a sociological sense) on the one hand and school as an institution on the other hand from which concrete ‘pedagogical contradictions’ arise (Helsper Citation2004; Citation2010).

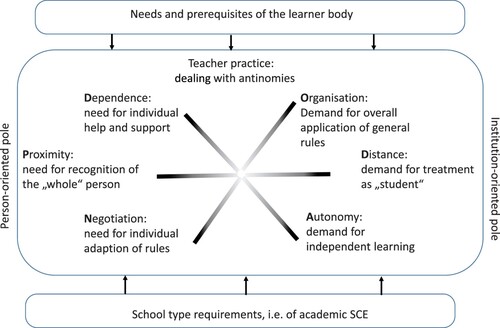

In order to moderate between individual needs and institutional demands, teachers develop relatively stable practices with regard to whether and how they give in to the needs of their students in concrete situations (Collins and Pratt Citation2011; Helsper Citation2004; Citation2010; Wernet Citation2003). Institutional demands and personal needs can therefore be understood as two ideal-typical poles on a continuum along which teacher practice can be located. It could be argued that pedagogical contradictions are of less importance in academic SCE because adults are already self-directed and independent learners, and teachers are (or should be) accompanying educators (Knowles Citation1970). However, within the specific framework of academic SCE as described in the introduction, concrete pedagogical contradictions emerge and need to be addressed. Helsper (Citation2004; Citation2010) has described in different contributions a varying number of pedagogical contradictions. In the following, we present three of them (see ). Our selection is based on our pilot study, in which we conducted interviews with students and teachers in academic SCE, and on the contradictions they most frequently talked about. We assume that they are characteristic of academic SCE and give reasons for this assumption.

2.1.1. Dependence vs autonomy

The goal of pedagogical efforts is fundamentally to enable learners to achieve autonomy, for instance by participating as equals in society. However, since learners are not yet in possession of the necessary knowledge and skills, they are treated – in a theoretical sense – as dependent, i.e. as individuals who need help, instructional support and guidance from their teachers (Riley Citation2011). This contradiction – like all other contradictions – cannot in general be resolved because there is no ‘correct’ strategy that can always be applied and, moreover, there is a risk of undesirable developments if an orientation towards one of the poles – the institution or the person – is overemphasized. If too much or too little help and support is given, learners cannot achieve autonomy. The amount and type of support to be provided depends on the situation and on the individual learner.

This may also be the case for academic SCE (Brookfield Citation2013; Galloway Citation2017; Merrill Citation2004; Pratt Citation1988; Sabourin Citation2012). Since learners do not have control over the goal (the eligibility to study), the time they spend in academic SCE and the curriculum, and since the demands of an academic track are particularly high, this first puts them in a dependent position from which they have to achieve autonomy (Ludwig Citation2022). The resulting contradiction may be compounded by the fact that the learners are adults, and for this reason, their teachers may expect them to need little or no support (Riley Citation2011). At the same time, some of them, e.g. those who have been out of compulsory schooling for a long time or who have a broken school career, may be particularly dependent on help and support (De Greef et al. Citation2012), and some teachers, aware of their learners’ precarious learning conditions, may be overly determined to provide help and support.

2.1.2. Proximity vs distance

From a sociological point of view, school contexts are structured in such a way that learners are not treated as ‘whole persons’ (as in the family) but in their role as learners (Dreeben Citation1968; Helsper Citation2004; Parsons Citation1959). More specifically, since many students are put together in one class, since (in secondary education) teachers are ‘specialists’ (taking a narrow interest in their own particular subject), since there is a change of teacher at the beginning of every school year, and since assessment is based on performance and not on personal preferences, relationships between teachers and students remain distant and role-based and not ‘holistic’ (like the relationship between mother and child). Studies have shown that a distant relationship between teacher and learner is particularly favoured in academic tracks (Baumert et al. Citation2004; Helsper Citation2012; see for non-academic tracks Lippke Citation2012). However, from a pedagogical perspective and in order to be actively involved in the learning process, learners must be seen and recognized as ‘persons’ with their biographical fractures and circumstances, and even more so if they have emotional, social and psychological burdens (Lippke Citation2012; Martins et al. Citation2020; Mottern Citation2012; Schuchart and Schimke Citation2021; Wärvik Citation2013).

One example is a learner who has difficulty concentrating in class due to family problems. Again, the contradiction between the demands of the institution (e.g. to assess everyone based on equal standards) and the demands of the person (to be recognized as a person within their particular circumstances) cannot in principle be solved. Too much proximity (=person) ignores learning development (Lippke Citation2012), and too much distance (=institution) endangers the ‘educational alliance’ between teachers and students. This pedagogical contradiction of proximity vs distance exists in academic SCE too, since as an academic track it structurally supports the existence of distanced relationships, but at the same time, and as has been already stated, many learners have social, emotional and psychological problems.

2.1.3. Negotiation vs organization

School as an institution is characterized by the formal structuring of pedagogical action by curricula, defined lesson times and timetables that are the same for all students. This is also the case in academic SCE and is reinforced by the emphasis teachers in academic SCE place on recording absences and adhering to disciplinary rules (Bellenberg et al. Citation2019). As in general education, the curricular requirements, defined lesson times, attendance requirements and standardized examinations generate disciplinary challenges. In contrast to general education, adult students have often taken on responsibilities in private and occupational contexts that make it difficult for them to be punctual, to attend classes and/or to keep to deadlines. They are therefore interested in interaction, i.e. in negotiating the validity of rules and adapting them to their life circumstances (Asselmeyer Citation1996).

Here too, a solution can only be found situationally: Too much organization (=sticking to rules) fails to take into account learners’ needs in their often challenging adult life circumstances (=negotiation), but too much negotiation would make teaching inefficient for all those concerned. Managing satisfactorily problems of negotiation vs organization is a challenge in adult education, and findings have for instance shown that dealing with discipline problems is one of the most important priorities for the professional development of adult educators (Sabatini et al. Citation2000).

Studies that have analysed the practice – in the broad sense of norms, attitudes and teaching strategies – developed by teachers have identified central characteristics such as beliefs about whether and how much individual help, support, recognition and encouragement teachers should offer students for their learning processes (Lange-Vester and Teiwes-Kügler Citation2014; Nairz-Wirth and Feldmann Citation2019; Schuchart and Bühler-Niederberger Citation2020). These beliefs are reflected in the choice of teaching methods and in the relationship that teachers build with learners, i.e. whether they are interested in them as persons or treat them purely as students (Thomas Citation2002). Lange-Vester and Teiwes-Kügler (Citation2014) describe these differences as differences between ‘pedagogues’ (who take personal needs into account) and ‘specialist teachers’ (who are oriented towards institutional demands by primarily focusing on their particular subject). ‘Pedagogues’ seem to react more than ‘specialist teachers’ adequately to the needs and prerequisites of learners with precarious learning prerequisites and from disadvantaged backgrounds (ibid).

2.2. Structural influences on teacher practice

We have mentioned above that structural challenges such as the conflict between the vulnerable student body and the academic goals and organization influence the choice of teacher practice. In the following, we describe this challenge in more detail by addressing (a) the possible needs of the student body in SCE, and (b) the requirements associated with the type of school (see ). We have already mentioned that teacher practice can be oriented more towards the institutional or the person pole of the pedagogical contradictions. If the practice is too strongly oriented towards one of these poles, this may hamper the positive development of students, as is described below.

2.2.1. Needs and prerequisites of the students

Students vary in the extent to which they expect a response to their personal situation. Those from disadvantaged social and ethnic backgrounds, low-performing students and students with social-emotional problems are more dependent on the support of teachers, particularly appreciate a caring and trusting relationship with teachers and have weaker performance-related self-esteem (Bremer Citation2007; Horvath and Davis Citation2011; Merrill Citation2004; Phillippo Citation2012; Reay Citation1998; Schuchart and Bühler-Niederberger Citation2020; Thomas Citation2002). Some studies suggest that the more teachers perceive their students as disadvantaged and at risk, the more they are likely to adopt a practice that tends towards meeting the needs and prerequisites of these students (in terms of proximity and dependence, e.g. Martins et al. Citation2020; Pratt Citation2002; Reese, Jensen, and Ramirez Citation2014; Weinstein, Tomlinson-Clarke, and Curran Citation2004). However, Helsper (Citation2010; Citation2012) identifies here a risk of an ‘entanglement’ near the personal pole of pedagogical contradictions, and teachers could tend to focus on the personal needs of students to the detriment of institutional demands such as learning goals or the demands for student autonomy. He illustrates this with the example of a teacher who dedicates a considerable amount of time to dealing with the social problems of students, which improves the classroom climate but reduces learning time (Lippke Citation2012).

2.2.2. Academic SCE

We have described in the introduction that the organization of academic SCE in Germany parallels that of senior classes of the Gymnasium in mainstream education. These can be characterized as clearly oriented towards institutional norms such as autonomy, distance and organization. Studies show that this kind of school structure hampers the employment of student-centred practices (Helsper Citation2012; Papaioannou and Gravani Citation2018). Helsper (Citation2012) points out that an academic structure increases the risk of teacher practice becoming ‘entangled’ near the institutional pole of the pedagogical contradictions, for instance by establishing distant, discipline-oriented and even dismissive relationships with students (Helsper Citation2010; Citation2012). Against the background of this structural challenge, our first question is: What are the types of teacher practice that can be distinguished in academic SCE, and can a dominant practice be identified? Although we have described a specific student body as a structural feature of academic SCE, this can vary between schools. Our second question is therefore: How is the practice of an individual teacher influenced by the student composition at their school?

2.3. The fit between teacher practice and students’ needs

We have stated that students do not have uniform needs and expectations with regard to school as these vary depending on their individual and family characteristics. This means that teachers who pursue a more person-oriented practice may reject those students who expect a more institution-oriented practice (Straehler-Pohl and Pais Citation2014). Since it is in particular vulnerable students who depend on a supportive and caring relationship with teachers, many previous studies have predominantly investigated the benefits of a student-centred, supportive and caring practice of teachers in adult education (e.g. Martins et al. Citation2020; Wärvik Citation2013). Second-chance students, however, are adults, and at least some of them want to be treated as responsible and autonomous students and value a relationship with their teachers in which they are treated as equals (Asselmeyer Citation1996; Bühler-Niederberger, Schuchart, and Türkyilmaz Citation2022; Darden Citation2014; Knowles Citation1970). Furthermore, they may be critical of a dependence-oriented attitude of other students and teachers (ibid). This example shows that in situations where teachers are confronted with multiple expectations, they can meet the needs of only some but not all of their students. Our third question is therefore: To what extent and in what aspects do teachers make their practice fit the expectations of their students?

3. Method

3.1. Sample

Data collection took place in the largest of Germany’s federal states, North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), where evening schools (in this study evening Gymnasiums) and daytime schools (Kollegs) form the group of ‘Weiterbildungskollegs’. The study was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Wuppertal.

The questionnaire was tested in a pilot study of n = 78 students and then adapted. In 2018/2019, we collected data from 176 teachers and 600 students in 9 randomly selected evening Gymnasiums and Kollegs of academic SCE (Second-Chance Education).Footnote3 Participation was voluntary, and teachers and students answered the questionnaires independently of each other. Strict anonymity was assured. Teachers were on average 49.95 (SD = .84) years old, students were 24.29 (SD = .20) years old.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Teacher practice (questions 1 and 2)

We asked teachers about their classroom practices (Frey et al. Citation2009, 291; Seidel Citation2003) that could be assigned to the three pedagogical contradictions described above using 17 items (): Five of the items recorded the extent to which teachers supported the learning processes of their students, e.g. by correcting additional practice tasks and showing special consideration in class for weak students (=dependence vs autonomy). Two items asked to what extent teachers were interested in their students’ personal life situations (=proximity vs distance). Six items were used to establish the extent to which teachers were willing to take into account the individual situation of students when setting disciplinary rules, deadlines for homework and when grading (=negotiation vs organization). We also asked teachers to what extent they adhered to the achievement requirements of academic SCE leading to a university entrance qualification (4 items). Teachers could indicate whether they adopted a certain practice 1 (always), 2 (very often), 3 (now and then), 4 (seldom), or 5 (never).

Table 1. Sample mean and latent class profiles of teacher practices (two-group solution, imputed data set, N = 176).

3.2.2. The teachers’ perception of the student composition at their school

Teachers were asked to indicate the percentage of their students who did not fulfil the academic requirements of SCE (M = 35.02, SD = 19.5), and the percentage of their students who were hampered in their learning process by serious personal and/or family problems (M = 38.88, SD = 17.88).

3.2.3. Control variables: teachers’ individual characteristics

Studies show that a teacher’s practice is influenced by individual characteristics (Helsper Citation2012; Velasquez et al. Citation2013; Lange-Vester and Teiwes-Kügler Citation2014). Against this background, we included the following teacher characteristics: sex, parental educational attainment, number of years of work experience in SCE, teachers of STEM subjects such as science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and also previous experience working at an academic institution. 41% of the teachers were male, 42% had parents who were graduates from university, their average working experience was 15.78 years (SD = .77), 37% taught STEM subjects and 73% previously worked at the general academic track or a university.

3.2.4. Expectations of teachers and students (question 3)

In order to answer question 3, we developed a number of items based on the work of Kischkel (Citation1979), Fend (Citation2008, 308) and the interviews in our pilot study. For the present study, we used five bipolar items on expectations concerning teacher practice, which were presented to both teachers and students (). These items refer to the three pedagogical contradictions in the following way: Expectations concerning how to deal with proximity vs distance were captured by two items on the interest teachers should or should not have in the personal situation of students and on whether teachers should be ‘personally impressive’ (i.e. impressive as persons). Two items captured expectations on whether teachers should take the personal circumstances of a student into account when recording absences and when grading (negotiation vs organization), and there was one item on expectations concerning whether teachers should explicitly motivate students who are having a difficult time (dependence vs autonomy).

Table 3. Latent class profiles of teachers and students of expectations on teacher practices (imputed dataset, N = 776).

All the items were formulated in a person-related sense (e.g. ‘Teachers should pay attention to students as persons, for instance by asking them how they are’) and in an institution-related sense (e.g. ‘Teachers should only pay attention to a student’s achievements and progress’). Respondents had to choose between 7 response categories. Higher values indicate a greater tendency towards institutional demands.

3.3. Analysis strategy

3.3.1. Imputation

Our data have missing values (see for the teacher sample and for the teacher and student sample). Multiple imputation (MI) is by far the best procedure to handle them in view of the various mechanisms that can drive item-nonresponse (see Rubin Citation1987; Van Buuren Citation2012). We therefore decided to impute the variables used for the models in the teacher sample as well as in the student sample with the Stata MI routine. We also ran LCA with the unimputed data (). The results were similar to the results obtained with the imputed dataset.

3.3.2. Latent class analysis

Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was conducted using 17 items (questions 1 and 2) and the responses of teachers and students to the five items on teacher practice (question 3). LCA is a statistical method to identify unmeasured group membership among individuals using observed variables. It was performed by using the program STATA 15.1. BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) was considered to select the solution with the best-fit indices (Enders and Tofighi Citation2008; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén Citation2007; Tofighi and Enders Citation2008). Group size and average latent class posterior probability (which predicts group membership for individuals) were also considered when choosing the best solution (Weller, Bowen, and Faubert Citation2020).

4. Results

4.1. Types of teacher practice and their distribution among the teachers

Our first question focused on what types of teacher practices can be distinguished in academic SCEs and whether a dominant practice can be identified. Based on suggestions for the selection of group solutions produced by LCA (Latent Class Analysis; Muthén and Muthén Citation2006; Weller, Bowen, and Faubert Citation2020; see for further explanations), we chose the two-group solution. In the following, we first describe the two groups and then interpret the findings.

One group (N = 110, 62.5%) is much larger than the other group (N = 66). According to its characteristics and following Lange-Vester and Teiwes-Kügler (Citation2014), the first group is referred to here as ‘the pedagogues’ and the second group as ‘the specialist teachers’ ().

Table 4. Summary of main research findings.

The pedagogues differ clearly from the specialist teachers since they are oriented much more strongly towards proximity (students are treated as persons) and dependence (instructional support for students is highly valued). The difference between the two groups is often about one unit of measurement. The pedagogues are also more inclined towards negotiation, which means that they consider the reasons why students are absent, they make exceptions to their rules on absence for students with children and they allow students to submit their homework when they are able to. However, the differences between the two groups are relatively small here, and there are no differences with respect to general discipline rules and universal grading criteria. The large size of the group of pedagogues indicates that this is how teachers respond to the structural challenge of SCE, namely by trying to address the perceived needs of a vulnerable student body while at the same time adhering to academic achievement goals.

In comparison to the pedagogues, the smaller group of specialist teachers (37.5%) is more oriented towards the demands of distant relationships and autonomy, and they are less inclined than the pedagogues to adapt disciplinary rules to individuals or vulnerable groups of students. As a group, they seem to be problematically entangled near the institution-oriented pole of the pedagogical contradictions since they tend to ignore the personal and learning needs of their students by prioritizing the demands of an academic institution. The size of this group in our data suggests, however, that in general, academic SCE, which was originally created to help disadvantaged students upgrade their school certificates, tends not to encourage this type of practice.

In all, there are clear differences between the two groups of teachers regarding the pedagogical contradictions dependence vs autonomy and proximity vs distance. However, when it comes to achievement requirements, pedagogues and specialists largely agree – despite their statistical differences – on the importance of maintaining a high level of performance. Although the pedagogues make more concessions in the pursuit of the qualification goal of SCE – the eligibility to study at a university – than the specialist teachers, they still adhere to the academic requirements of SCE. This is an indication that they do not become problematically entangled near the personal pole of the pedagogical contradictions, which would mean neglecting academic and universal standards on achievement and grading.

4.2. Influence of student body on teacher practice

Our second question concerns the extent to which an individual teacher's practice is influenced by the composition of the student body in their school. In order to estimate the impact of the teachers’ perception of the student body on group membership (), we calculated two models (LCA with covariates). In the first model (M1), we consider only the individual control variables since they could already explain the differences between the two groups of pedagogues and specialist teachers. Confirming previous results (Bellenberg et al. Citation2019; Helsper Citation2012; Nolan Citation2012; Velasquez et al. Citation2013), the probability that a teacher belongs to the group of specialist teachers is lower for women, and it is higher for teachers who teach STEM subjects and for teachers who previously taught at the general academic track or a university. The social background of teachers and their job experience is not of importance for group affiliation.

Table 2. Latent class profiles of teacher practice and covariates (imputed dataset, N = 176).

In order to investigate the impact of school characteristics on group affiliation, we include in the second model the measurement of the teachers’ perception of the student body (M2). The more teachers perceive students as having non-adequate cognitive prerequisites, the stronger the likelihood that they belong to the group of specialist teachers. However, an increase in the perception of non-adequate personal and family prerequisites is associated with a slight increase in the likelihood of belonging to the group of pedagogues (significant at the 10% level).

In theory, we expected that an increasing perception of a vulnerable student body could be associated with a greater likelihood of choosing a person-oriented rather than an institution-oriented practice (Helsper Citation2012). However, the perception of a socially and individually disadvantaged student body is only weakly associated with an increase in the likelihood of belonging to the group of pedagogues, who pay much more attention to the personal circumstances of students than do the specialists. Instead, there is a stronger indication that the more teachers perceive students as having non-adequate cognitive prerequisites, the more likely it is that they belong to the group of specialists, meaning that they are more likely to decide not to support the learning of their students by practising with them, providing extra learning materials and helping them to understand the subject matter of the lessons. This is an indication that under the conditions of an academic school type, an increase in the proportion of students with non-adequate learning prerequisites increases the risk of the teacher becoming entangled at the institutional pole of the pedagogical contradictions.

4.3. Fit between teachers practice and expectations of students

Our third question addresses the alignment of teachers’ practice with the expectations of their students. In order to answer this question, we ran an LCA on the expectations of students and teachers regarding teacher actions. The assumption is that the more equal the distributions of students and teachers over one or more groups, the more this indicates a fit between the expectations of students and teachers. Based on the suggestions of Weller, Bowen, and Faubert (Citation2020) we chose the five-group-slution (see for further explanations). The findings show only a partial match between teachers and students:

The largest group 1 comprises 37% of the sample (). Compared to those in other groups, teachers and also students have a higher level of expectations that teachers are interested in the personal circumstances of a student and consider a student’s personal circumstances when grading and reporting absences. Like those in group 2, they also expect teachers to motivate students if they are having a difficult time and to be ‘personally impressive’. Thirty-nine percent of all students and 28% of all teachers belong to this group. Seventy-four percent of teachers in this group belong to the group of pedagogues according to the results of the teachers-only analyses (4.1). The second largest group (25%) is characterized by the expectation that teachers should be ‘personally impressive’, should motivate unmotivated students and should be interested in their personal circumstances. However, members of this group also expect teachers to enforce absence rules and not to take into account personal circumstances when grading. 15% of all students and 56% of all teachers belong to this group.

The remaining three groups are much smaller. The third group (23%) comprises teachers and students who have average scores on all variables – its members expect teachers to have an intermediate position between the poles personal needs and institutional demands. Group four (11%) and group five (5%) both consist of participants who – compared to the members of other groups – are more systematically oriented towards the institution-oriented pole of the pedagogical contradictions. They expect teachers to be interested in the achievements of students rather than in their personal circumstances, to report them if they are late, and to enforce the reporting of absences. Although there are differences between the two groups regarding individual items, the orientation towards the institutional pole is clear. Both groups consist almost entirely of students.

This analysis offers a further perspective, revealing that the differences in teacher practice reported by teachers may be smaller than the differences in expectations on teacher practice reported by teachers and students. The analysis shows that there is only a partial match between teachers and students concerning the membership of the groups. In particular, three main results can be highlighted. First, the profiles of about 85% of the teachers (groups 1 and 2) match those of 55% of the students. These groups have in common that they expect teachers to be oriented towards proximity, negotiation and dependence. Second, however, the majority of teachers (group 2) are more organization-oriented in terms of absence rules than most of the students expect them to be. And third, about 20% of students clearly support a position oriented towards the institutional pole of the pedagogical contradictions, a position shared by almost none (i.e. 3%) of the teachers. The majority of the teachers are characterized by the fact that they tend to be oriented towards proximity and dependence but emphasize the institutional side with regard to universal rules for absence and grades, while the expectations of about half of the students are oriented to a greater extent than their teachers towards distance and autonomy, and at least 65% are more likely than their teachers to be oriented towards more flexible rules for discipline and grading. In principle, these differences point to the dilemma that by orienting themselves towards students in need of support and care, teachers tend to reject those who want more distance and autonomy.

5. Conclusion

In Germany, half of the students drop out of academic SCE (Second-Chance Education) and do not achieve their goal of obtaining the eligibility to study. The results of our explorative analyses (see for a summary of results ) seem to provide some indications as to what can be improved in academic SCE to lead more students to success, which may also apply in countries with a similarly highly formalised academic SCE. Here we highlight the following aspects: Firstly, the LCA analyses suggest that the group of pedagogues in particular are attempting to come to terms with the pedagogical contradictions by maintaining academic goals while still being person-oriented, which could be more accurately described as professional student-oriented practice. Other studies have already suggested that combining challenging instruction with individualized attention to students’ learning but also to their personal needs is one way to deal successfully with the challenge of guiding vulnerable students through academic SCE to the eligibility to study at a university (see e.g. Athanases et al. Citation2016).

Secondly, a certain, albeit small, proportion of teachers that we have called ‘specialist teachers’ seem to be at risk of becoming entangled at the institutional pole of pedagogical contradictions, as they tend to prefer distanced relationships with students and emphasize disciplinary rules. Research shows that a certain degree of closeness to students is conducive to the development of an ‘educational alliance’ between teachers and their students and helps students to engage actively in the learning process (see also Schuchart and Buehler-Niederberger 2020; Telio, Ajjawi, and Regehr Citation2015). The specialist teachers score especially low on the relationship scale and this raises the question whether they succeed sufficiently often in establishing ‘educational alliances’ with students, even with those who value a certain professional distance. The probability of belonging to the group of specialist teachers increases when accompanied by certain personal characteristics. These include previous employment at an academic track in general education or university. At such strictly academic types of education institutions with a very privileged student body, these teachers may have been successful with a practice that does not seem to function well in academic SCE. This raises the question whether SCE teachers with experience at an academic institution should be offered training courses during which they are introduced to working in academic SCE.

Thirdly, a clear effect was found for the perception of a lack of cognitive prerequisites on the part of the student body. However, in the case of such a subjective perception, teachers do not react by increasing their instructional and pedagogical efforts, but instead retreat to their role as technical instructors. This may be an effect caused by the particular tension between academic demands and the precarious learning conditions of part of the student body. The teachers may feel overwhelmed when they perceive too great a distance between the demands and the student prerequisites. Since the schools included hardly differed in terms of the objective composition of their students, in particular teachers with a lower level of instructional and pedagogical skills may perceive greater deficits in their students. This should be responded to in the future with more in-service training for teachers who address the challenges of teaching adult students under the structural framework of academic SCE.

Fourthly, our results contradict other findings, especially those from qualitative research, according to which problems of students with a low-privileged background at institutions of higher education are partly due to the fact that their expectations for personal attention and interest from teachers are not met (Merrill Citation2004; Thomas Citation2002). One explanation could be that in our study, the students participate in academic SCE (and not at institutions of higher education) and are treated structurally as school students, thereby questioning their status as adults (Asselmeyer Citation1996). While from the teachers’ perspective, the perception of a student body in need of pedagogical attention may predominate, the self-perception of a considerable number of students is more strongly oriented towards expectations of autonomy and distance.

However, the considerable heterogeneity among students regarding not only their prerequisites, but also the level of their personal needs indicates a dilemma: If teachers respond to the significant proportion of learners who expect their adult role to be taken seriously, they may reject those learners who need more guidance, support and care. The question here is whether this dilemma can be solved – for example by means of an orientation away from traditional general school structures in favour of a stronger orientation towards adult education structures, materials and methods as well as accompanying support systems for those who need them – thereby creating structurally a more professional approach where adult learners are concerned.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The range of basic and advanced courses in the subjects Mathematics, German, English, History, Politics, Social Studies, Geography, Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Religion, French or Latin corresponds to the range offered in Gymnasiums. Whether there are courses in Computer Science or other languages depends on the individual school.

2 Helsper calls them “pedagogical antinomies”, but since the term “antinomy” is in the English-speaking world primarily known as the mutual incompatibility of two laws and is used in logic and epistemology (see e.g. Kant [Citation1781] Citation1990), we have preferred not to use this term.

3 Access to the data can be given by the authors upon request.

References

- Asselmeyer, H. 1996. Einmal Schule – Immer Schüler? Eine empirische Studie zum Lernverständnis Erwachsener. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Athanases, S. Z., B. Achinstein, M. W. Curry, and R. T. Ogawa. 2016. “The Promise and Limitations of a College-Going Culture: Toward Cultures of Engaged Learning for low-SES Latina/o Youth.” Teachers College Record 118 (7): 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811611800708

- Ball, S. J. 2003. “The Teacher’s Soul and the Terrors of Performativity.” Journal of Education Policy 18 (2): 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Baumert, J., M. Kunter, M. Brunner, S. Krauss, W. Blum, and M. Neubrand. 2004. “Mathematikunterricht aus Sicht der PISA- Schülerinnen und -Schüler und Ihrer Lehrkräfte.” In PISA 2003. Der Bildungsstand der Jugendlichen in Deutschland – Ergebnisse des zweiten internationalen Vergleichs, edited by M. Prenzel, J. Baumert, W. Blum, R. Lehmann, D. Leutner, M. Neubrand, R. Pekrun, H.-G. Rolff, J. Rost, and U. Schiefele, 283–354. Münster and New York: Waxmann.

- Bellenberg, G., G. Im Brahm, D. Demski, S. Koch, and M. Weegen. 2019. Bildungsverläufe an Abendgymnasien und Kollegs (Forschungsförderung Nummer 115). Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

- Bremer, H. 2007. Soziale Milieus, Habitus und Lernen: Zur sozialen Selektivität des Bildungswesens am Beispiel der Weiterbildung. Juventa Verlag.

- Brookfield, S. 2013. “The Essence of Powerful Teaching.” International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology (IJAVET) 4 (3): 67–76. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijavet.2013070107.

- Bühler-Niederberger, D., C. Schuchart, and A. Türkyilmaz. 2022. “Doing Adulthood While Returning to School. When Emerging Adults Struggle with Institutional Frameworks.” Emerging Adulthood 11 (1): 148–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968211069214.

- Collins, J., and D. D. Pratt. 2011. “The Teaching Perspectives Inventory at 10 Years and 100,000 Respondents: Reliability and Validity of a Teacher Self-Report Inventory.” Adult Education Quarterly 61 (4): 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713610392763.

- Darden, C. D. 2014. “Relevance of the Knowles Theory in Distance Education.” Creative Education 5 (10): 809–812. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.510094.

- De Greef, M., D. Verté, and M. S. R. Segers. 2012. “Evaluation of the Outcome of Lifelong Learning Programmes for Social Inclusion: A Phenomenographic Research.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 31 (4): 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2012.663808.

- Desjardins, R. 2017. Political Economy of Adult Learning Systems. A Comparative Study of Strategies, Policies and Constraints. London: Bloomsbury.

- Dreeben, R. 1968. On What is Learned in School. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Enders, C. K., and D. Tofighi. 2008. “The Impact of Misspecifying Class-Specific Residual Variances in Growth Mixture Models.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 15 (1): 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701758281.

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. 2018. The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Fend, Helmut. 2008. Schule gestalten. Systemsteuerung, Schulentwicklung und Unterrichtsqualität. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Freitag, W. K. 2012. Zweiter und Dritter Bildungsweg in die Hochschule (Bildung und Qualifizierung, 253). Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

- Frey, A., P. Taskinen, K. Schütte, M. Prenzel, C. Artelt, J. Baumert, W. Blum, K. E. Hammann, and R. Pekrun. 2009. PISA 2006. Skalenhandbuch. Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. Münster: Waxmann.

- Galloway, S. 2017. “Flowers of Argument and Engagement? Reconsidering Critical Perspectives on Adult Education and Literate Practices.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 36 (4): 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2017.1280859

- Glorieux, I., R. Heyman, M. Jegers, and M. Taelman. 2011. “Who Takes a Second Chance? Profile of Participants in Alternative Systems for Obtaining a Secondary Diploma.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 30 (6): 781–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2011.627472.

- Harney, K. 2016. “Zweiter Bildungsweg als Teil der Erwachsenenbildung.” In Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung, edited by R. Tippelt and A. von Hippel, 837–856. Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

- Harney, K., S. Koch, and H. Hochstätter. 2007. “Bildungssystem und Zweiter Bildungsweg: Formen und Motive reversibler Bildungsbeteiligung.” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 53 (1): 34–57.

- Helsper, W. 2004. “Pädagogisches Handeln in den Antinomien der Moderne.” In Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Grundfragen der Erziehungswissenschaft: Vol. 1 Einführung in die Grundbegriffe und Grundfragen der Erziehungswissenschaft, edited by H. H. Krüger, and W. Helsper, 6th ed., 15–32. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-09887-4_2.

- Helsper, W. 2010. “Pädagogisches Handeln in den Antinomien der Moderne.” In Einführungskurs Erziehungswissenschaft: Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Grundfragen der Erziehungswissenschaft, edited by H. H. Krüger, and W. Helsper, 15–32. Opladen: Budrich.

- Helsper, W. 2012. “Die Antinomie von Nähe und Distanz in unterschiedlichen Schulkulturen: Strukturelle Bestimmungen und empirische Einblicke.” In Professionalität im Umgang mit Spannungsfeldern der Pädagogik, edited by C. Nerowski, T. Hascher, M. Lunkenbein, and D. Sauer, 27–46. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

- Horvat, E. M., and J. E. Davis. 2011. “Schools as Sites for Transformation: Exploring the Contribution of Habitus.” Youth & Society 43: 142–170.

- Kade, J. 2005. “Wissen und Zertifikate. Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung als Wissenskommunikation.” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 51 (4): 498–512.

- Kant, I. [1781] 1990. Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Hamburg: Felix Meiner Verlag.

- Kischkel, K.-H. 1979. Gesamtschule und dreigliedriges Schulsystem in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Einstellungen, Zufriedenheit und Probleme der Lehrer. Paderborn: Schöningh.

- Knowles, M. S. 1970. The Modern Practice of Adult Education: Andragogy Versus Pedagogy. New York: Association Press.

- Koch, S. 2018. Die Legitimität der Organisation: Eine Untersuchung von Legitimationsmythen des Zweiten Bildungswegs. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Lange-Vester, A., and C. Teiwes-Kügler. 2014. “Habitussensibilität im schulischen Alltag als Beitrag zur Integration ungleicher sozialer Gruppen.” In Habitussensibilität: Eine neue Anforderung an professionelles Handeln, edited by T. Sander, 177–207. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06887-5_8.

- Lippke, L. 2012. “Who am I Supposed to let Down?” Journal of Workplace Learning 24 (7/8): 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621211260972.

- Looker, E. D., and V. Thiessen. 2008. The Second Chance System: Results from the Three Cycles of the Youth in Transition Survey. Human Resources and Social Development Canada.

- Ludwig, J. 2022. Subjekt und Subjektentwicklung im erwachsenenpädagogischen Diskurs. In Hessischer Volkshochschulverband e. V. (hvv) (ed.), Hessische Blätter für Volksbildung (HBV), 3. https://doi.org/10.3278/HBV2203W005.

- Marcotte, J. 2012. “Breaking Down the Forgotten Half: Exploratory Profiles of Youths in Quebec’s Adult Education Centers.” Educational Researcher 41 (6): 191–200. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12445319.

- Martins, F., A. Carneiro, L. Campos, L. M. Ribeiro, M. Negrâo, I. Baptista, and R. Matos. 2020. “The Right to a Second Chance: Lessons Learned from the Experience of Early School Leavers who Returned to Education.” Pedagogia Social 36:139–152. https://doi.org/10.7179/PSRI_2020.36.09.

- Merrill, B. 2004. “Biographies, Class and Learning: The Experience of Adult Learners.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 12 (1): 73–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360400200190.

- Mottern, R. 2012. “Educational Alliance: The Importance of Relationships in Adult Education with Court-Mandated Students.” Adult Learning 23 (3): 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/1045159512452409.

- Muthén, B., and L. Muthén. 2006. “Integrating Person-Centered and Variable-Centered Analyses: Growth Mixture Modeling with Latent Trajectory Classes.” Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research 24 (6): 882–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x.

- Nairz-Wirth, E., and K. Feldmann. 2019. “Teacher Professionalism in a Double Field Structure.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 40 (6): 795–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1597681.

- Nolan, K. 2012. “Dispositions in the Field: Viewing Mathematics Teacher Education Through the Lens of Bourdieu 's Socialfield Theory.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 80: 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-011-9355-9.

- Nylund, K. L., T. Asparouhov, and B. O. Muthén. 2007. “Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study.” Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14 (4): 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. Education at a Glance Interim Report: Update of Employment and Educational Attainment Indicators.

- Orr, D., A. Usher, C. Haj, G. Atherton, and I. Geanta. 2017. Study on the Impact of Admission Systems on Higher Education Outcomes. Volume I: Comparative report. Brussels: European Commission.

- Papaioannou, E., and M. N. Gravani. 2018. “Empowering Vulnerable Adults Through Second-Chance Education: A Case Study from Cyprus.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 37 (4): 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2018.1498140.

- Parsons, T. 1959. “The School Class as a Social System: Some of its Functions in American Society.” Harvard Educational Review 29 (4): 297–318. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315408545-9.

- Phillippo, K. 2012. “You’re Trying to Know me: Students from Nondominant Groups Respond to Teacher Personalism.” Urban Review 44 (4): 441–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-011-0195-9

- Pratt, D. 1988. “Andragogy as a Relational Construct.” Adult Education Quarterly 38 (3): 160–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001848188038003004

- Pratt, D. D. 2002. “Good Teaching: One Size Fits all?” In An up-Date on Teaching Theory, edited by J. Ross-Gordon, 5–16. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Raymond, M. 2008. Décrocheurs du secondaire retournant à l’école. Division de la Culture, tourisme et centre de la statistique de l’éducation Immeuble principal.

- Reay, D. 1998. “Rethinking Social Class: Qualitative Perspectives on Gender and Social Class.” Sociology 32 (2): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038598032002003

- Reese, L., B. Jensen, and D. Ramirez. 2014. “Emotionally Supportive Classroom Contexts for Young Latino Children in Rural California.” The Elementary School Journal 114 (4): 501–526. https://doi.org/10.1086/675636.

- Riley, P. 2011. “Rousseau's Philosophy of Transformative, ‘Denaturing’ Education.” Oxford Review of Education 37 (5): 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2011.626930.

- Ross, S., and J. Gray. 2015. “Transitions and re-Engagement Through Second Chance Education.” The Australian Educational Researcher 32 (3): 103–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216829

- Rubin, D. B. 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sabatini, J. P., M. Daniels, L. Ginsburg, K. Limeul, M. Russell, and R. Stites. 2000. Teacher Perspectives on the Adult Education Profession: National Survey Findings About an Emerging Profession. Washington: Office of Vocational and Adult Education. https://doi.org/10.1037/e407002005-001.

- Sabourin, E. 2012. “Education, Gift and Reciprocity: A Preliminary Discussion.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 32 (3): 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2012.737376.

- Schuchart, C., and D. Bühler-Niederberger. 2020. “The gap Between Learners’ Personal Needs and Institutional Demands in Second Chance Education in Germany.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 35 (5–6): 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2020.1825538.

- Schuchart, C., and B. Schimke. 2021. “Age and Social Background as Predictors of Dropout in Second Chance Education in Germany.” Adult Education Quarterly 72 (3): 308–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/07417136211046960.

- Seidel, T. 2003. Lehr-Lernskripts im Unterricht. Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

- Seitter, W. 2009. “Bildungsverläufe im zweiten Bildungsweg. Empirische Befunde der Teilnehmer- und Adressatenforschung.” Hessische Blätter für Volksbildung 59 (3): 227–237. https://doi.org/10.3278/HBV0903W227

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2021. Bildung und Kultur – Allgemeinbildende Schulen (Fachserie 11, Reihe 1). Statistisches Bundesamt.

- Straehler-Pohl, H., and A. Pais. 2014. “Learning to Fail and Learning from Failure – Ideology at Work in a Mathematics Classroom.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 22 (1): 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2013.877207.

- Telio, S., R. Ajjawi, and G. Regehr. 2015. “The “Educational Alliance” as a Framework for Reconceptualizing Feedback in Medical Education.” Academic Medicine 90 (5): 609–614. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560.

- Thomas, L. 2002. “Student Retention in Higher Education: The Role of Institutional Habitus.” Journal of Education Policy 17 (4): 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930210140257.

- Tofighi, D., and C. K. Enders. 2008. “Identifying the Correct Number of Classes in Growth Mixture Models.” In Advances in Latent Variable Mixture Models, edited by G. R. Hancock and K. M. Samuelsen, 317–341. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Van Buuren, S. 2012. Flexible Imputation of Missing Data. New York: CRC Press.

- Velasquez, A., R. E. West, C. R. Graham, and R. D. Osguthorpe. 2013. “Developing Caring Relationships in Schools: A Review of the Research on Caring and Nurturing Pedagogies.” Review of Education 1 (2): 162–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3014.

- Wärvik, G.-B. 2013. “The Reconfiguration of Adult Education VET Teachers: Tensions Amongst Organisational Imperatives, Vocational Ideals and the Needs of Students.” International Journal of Training Research 11 (2): 122–134. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijtr.2013.11.2.122.

- Weinstein, C. S., S. Tomlinson-Clarke, and M. Curran. 2004. “Toward a Conception of Culturally Responsive Classroom Management.” Journal of Teacher Education 55 (1): 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487103259812.

- Weller, B. E., N. K. Bowen, and S. J. Faubert. 2020. “Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice.” Journal of Black Psychology 46 (4): 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798420930932.

- Wernet, A. 2003. Pädagogische Permissivität: Schulische Sozialisation und pädagogisches Handeln jenseits der Professionalisierungsfrage. Leske und Budrich.

Appendix

Table A1. Fit statistics and group size for different group solutions (LCA).

Table A2. Fit statistics, group size and example items, unimputed data set.