ABSTRACT

Since European colonisation of Australia in 1788, nine Australian bird species (1.2% of the Australian total) have become extinct, along with 22 subspecies (of 16 species). Consistent with global patterns, Australia’s island endemic birds have been particularly susceptible, comprising eight of the nine species’ extinctions (38% of the bird species endemic to islands smaller than Tasmania), and 13 of the 22 subspecies’ extinctions. The extinction of only one bird species (Paradise Parrot Psephotellus pulcherrimus) from the Australian mainland contrasts with the far higher rate of extinctions of Australian mammals (27 of 312 species that occurred on the Australian mainland), and is comparable with the rate of extinctions of birds on the mainland of other continents over this period. Extinctions of Australian birds were caused mainly by introduced predators (especially for island taxa), habitat degradation, and hunting (for some island taxa). The timing of some extinctions is uncertain, but the first bird extinction subsequent to European colonisation was the loss of the flightless White Gallinule Porphyrio albus from Lord Howe Island over the period 1788–1790. Extinctions have occurred in most decades since then, with the most recent being for Norfolk Island’s White-chested White-eye Zosterops albogularis in the decade 2000–2009. Environmental legislation, an extensive conservation reserve system, and dedicated conservation management efforts have prevented some extinctions. However, local extirpations continue, many threatened species continue to decline and, without an increase in conservation efforts, the rate of extinctions is likely to increase, mainly due to the direct and compounding impacts of climate change.

KE Y POLICY HIGH LIGHTS

Extinctions of Australian birds have occurred in most decades since European colonisation of Australia.

Island bird taxa have proven particularly susceptible, and many of the most imperilled birds are island endemics.

Conservation management actions and policies have prevented (and continue to do so) some otherwise probable extinctions.

The direct and indirect impacts of climate change will increase the likelihood of extinction for many bird taxa.

There is uncertainty about the persistence or extinction of some bird taxa, and these are priorities for surveys and, if found, urgent management interventions.

Introduction

European colonisation of Australia in 1788 has resulted in broad-scale transformation of most of its environments (Woinarski et al. Citation2015; Bergstrom et al. Citation2021). Much of Australia’s distinctive biodiversity – a legacy of the continent’s long isolation – was, and continues to be, severely affected by many factors associated with the changes wrought since colonisation. Those factors include major changes in fire regimes (Bowman et al. Citation2020), extensive clearance of some habitats (Bradshaw Citation2012; Ward et al. Citation2019), environmental degradation due to livestock and introduced herbivores (Morton et al. Citation2011), introduction of predators and diseases (e.g. Legge et al. Citation2017), hunting and exploitation, water extraction and major transformation of many aquatic systems (Kingsford et al. Citation2017), other resource use (such as timber harvesting), and also by increases in some native species with consequent impacts on other native species (Woinarski Citation2019). More recently, the many consequences of global climate change are becoming evident, resulting in increased incidence of severe disturbance events (including days of extreme heat, drought, and wildfire) (Nolan et al. Citation2021) and contraction of some susceptible environments. Many of these factors impose a direct, severe and continuing toll on Australian birds.

Here we review extinctions in the Australian bird fauna since 1788, assess some characteristics of those extinctions, and document the causal factors. We also compare the tally of Australian bird extinctions with those for other Australian vertebrate groups, and with tallies of extinctions of bird species globally.

Extinction is the end point of a trajectory and process of decline, sometimes rapid and sometimes gradual. Many Australian bird species have experienced extirpations (local extinctions) of some populations or across parts of their range, and we do not attempt to document those population losses comprehensively here. Furthermore, there is an ongoing trend for decline in Australia’s threatened birds, rendering them ever closer to extinction: for example, the average population size of 65 monitored Australian threatened bird taxa declined by 44% over the period 2000 to 2016 (Bayraktarov et al. Citation2021). With such trends, further extinctions of Australian bird species are likely in the near future (Geyle et al. Citation2018; Garnett et al. Citation2022).

The documentation here of Australian bird extinctions since European colonisation is based on the most recent assessment of the conservation status of Australian bird taxa by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021). Not included are some notable losses of the Australian bird fauna before European colonisation. Many losses, including of some of the most distinctive components of the Australian avifauna such as the giant mihirungs (Dromornithidae; Worthy and Nguyen Citation2020), occurred subsequent to Indigenous settlement of Australia, most likely associated with periods of marked climate change compounded by human hunting (Murray and Vickers-Rich Citation2004). At a far more local scale, the settlement of Norfolk Island by Polynesians over the period ca. 1150 to 1450 AD also resulted in extirpation of some bird species there, by direct human predation and predation by the introduced Pacific Rat Rattus exulans (Holdaway and Anderson Citation2001; Lombal et al. Citation2020).

Inventory of Australian bird extinctions

Nine bird species endemic to Australia have become extinct since European colonisation in 1788 (): this represents 1.2% of the complement of 753 Australian native (non-vagrant) bird species at 1788, and 2.5% of the 363 Australian endemic bird species. Only one of these now extinct species, the Paradise Parrot Psephotellus pulcherrimus, occurred on the Australian mainland (0.15% of the mainland bird species). In contrast, the eight extinctions of bird species endemic to Australian islands represent 22% of the Australian island endemic bird fauna (36 species), with this proportion even higher (38%) for islands smaller than Tasmania (64,519 km2) – eight extinctions from 21 Australian bird species endemic to islands smaller than Tasmania. Bird species endemic to the oceanic Lord Howe (15.9 km2) and Norfolk Island (36 km2) groups (collectively <0.001% of the total Australian land mass) have contributed disproportionately to extinctions, with five of the 10 species that were endemic to these islands now extinct.

Table 1. List of Australian bird extinctions and possible extinctions, derived from Garnett and Baker (Citation2021).

In addition to the nine extinctions of Australian endemic bird species, 22 Australian endemic bird subspecies have become extinct (including both subspecies of Tasman Starling; ). Along with the extirpation of the Australian population of Pycroft’s Petrel Pterodroma pycrofti, these losses have resulted in the extirpation of the entire Australian population(s) of five species extant elsewhere in the world ().

Most of the taxa recognised as extinct in Garnett and Baker (Citation2021) are also listed as extinct under Australia’s national environmental legislation, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) (). The most notable inconsistencies are that the EPBC Act has not yet recognised the extinction of the Mount Lofty Ranges Spotted Quail-thrush Cinclosoma punctatum anachoreta, Southern Star Finch, and some subspecies of Western Grasswren Amytornis textilis and Thick-billed Grasswren A. modestus.

In most cases, the extinctions are unequivocal. However, a few cases remain uncertain. There is a small possibility of persistence for some taxa considered by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021) to be extinct, notably for the Mount Lofty Ranges Spotted Quail-thrush Cinclosoma punctatum anachoreta, Southern Star Finch Neochmia ruficauda ruficauda (both taxa with records in the 1990s) and White-chested White-eye Zosterops albogularis (with records in the decade 2000–2009), but analysis using the threats model of extinction (Keith et al. Citation2017) and the records and surveys model (Thompson et al. Citation2017), indicates that persistence of these taxa is highly improbable (Garnett and Baker Citation2021).

Conversely, some poorly known taxa not considered extinct by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021), and hence not included in the tallies here, may be extinct. Based on expert elicitation, Garnett et al. (Citation2022) considered that there was a >50% likelihood that four bird taxa noted as extant by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021) were actually extinct. Two of these taxa are listed by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021) as Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct): Tiwi Hooded Robin Melanodryas cucullata melvillensis (with the most recent confirmed sighting in 1992) and Cape Range Rufous Grasswren Amytornis striatus parvus (with no confirmed records since 1974). The other two, Coxen’s Fig-parrot Cyclopsitta coxeni and Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivii, are assessed as Critically Endangered by Garnett and Baker (Citation2021).

Original distributions of extinct Australian birds

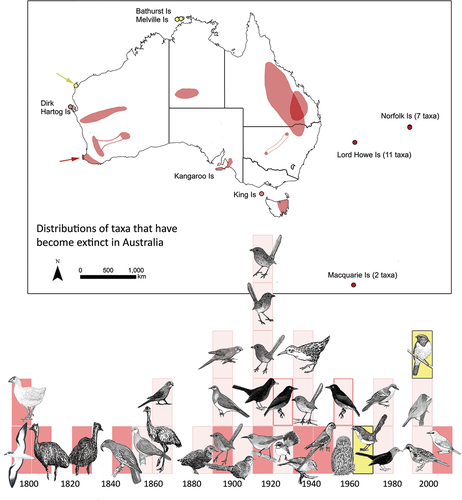

As described above, most Australian bird extinctions have been of taxa restricted to islands: Lord Howe, Norfolk (and the nearby Phillip Island: 1.9 km2), Macquarie (131 km2), Dirk Hartog (628 km2), King (1091 km2), Kangaroo (4416 km2) and Tasmania (). The former distributions of some now extinct mainland bird taxa are poorly resolved (e.g. the Western Australian Lewin’s Rail Lewinia pectoralis clelandi is known from only seven specimens taken from three or four locations: Garnett and Baker (Citation2021)). However, most had small and disparate ranges, with partly overlapping former distributions only in south-western Australia (for Western Australian Lewin’s Rail and Western Rufous Bristlebird Dasyornis broadbenti litoralis) and north-eastern Australia (minor range overlap for Paradise Parrot and Southern Star Finch). No bird extinctions have occurred in the monsoonal tropics of north-western Australia or in temperate mainland south-eastern Australia. The largest former distribution of a now extinct Australian bird taxon was probably for the Southern Star Finch, at about 64,000 km2 (Ward et al. Citation2022). The median area of occupancy for Australian extinct bird taxa was 38 km2.

Figure 1. Upper panel: The former range of bird species and subspecies that have become extinct in Australia. The small distribution of the Western Rufous Bristlebird overlaps with that of the Western Australian Lewin’s Rail, and is therefore highlighted with a red arrow. Small islands are shown with a shaded dot to enhance visibility. Two possible extinctions, Tiwi Hooded Robin and Cape Range Rufous Grasswren are shaded yellow, and the distribution of the latter is further highlighted with a grey-yellow arrow. Lower panel: The timing of Australian bird extinctions (darker boxes indicate species; lighter boxes subspecies; yellow boxes the two possible extinctions).

Timing of Australian bird extinctions

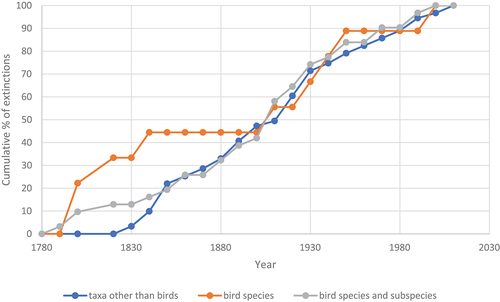

Bird extinctions began soon after European colonisation of Australia (; ), mostly due to hunting of species endemic to islands that were rapidly colonised or exploited. The last individuals of the White Gallinule (van Grouw and Hume Citation2016) and King Island Emu Dromaius minor were killed by about 1800, the Kangaroo Island Emu Dromaius baudinianus by 1820 and Norfolk Island Kaka Nestor productus by 1840. These losses largely preceded the first post-1788 extinctions of other Australian plant and animal species (; Woinarski et al. Citation2019). Hunting was a primary cause of extinctions of other bird taxa up to about the 1890s (including Norfolk Island New Zealand Pigeon Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae spadicea), but not thereafter.

Figure 2. Cumulative percentage of extinctions across decades for Australian bird species (brown: N = 9), Australian bird taxa (grey: N = 31), and Australian plant and animal species other than birds (blue: N = 91), with each expressed as a percentage of the total number of extinctions of that group over the period 1780–2022. Dating of non-bird extinctions is derived from Woinarski et al. (Citation2019).

Although the rate of extinction of Australian bird taxa has been relatively consistent over the period 1790 to 2020 (at about 1.3 taxa per decade), there have been spikes following the introduction of Black Rats Rattus rattus to Lord Howe Island (in 1918) and Norfolk Island (in the 1940s). The loss of several grasswren subspecies coincided with habitat degradation due to the expanding population of rabbits and to pastoralism, around the 1920s.

Most Australian bird extinctions pre-dated the establishment, mostly from the 1980s, of Australia’s modern conservation framework of specific environmental legislation including for the protection of threatened species, the development of a reasonably comprehensive conservation reserve system, and targeted conservation management actions. In most cases, there was little attempt made to avert these earlier extinctions, and no legislative basis for such an objective.

However, some extinctions have occurred subsequent to broad societal recognition and support for biodiversity conservation, and these losses represent failures of protective legislation and management. The most recent extinctions of Australian birds have been of Mount Lofty Ranges Spotted Quail-thrush, Southern Star Finch (with records in the 1990s) and White-chested White-eye (with the most recent confirmed records in the decade 2000–2009). As with recent Australian extinctions in other taxonomic groups (Woinarski et al. Citation2017), the loss of these bird taxa has been due in part to inadequacies in legislation, insufficient resourcing, lack of appropriately targeted recovery planning and its implementation, insufficient research and monitoring, and lack of effective champions.

The implications of taxonomy

Taxonomic resolution influences the recognition of extinctions. The Mount Lofty Ranges Spotted Quail-thrush was described as separate subspecies in 1999 (Schodde and Mason Citation1999), the year of the last credible record (Carpenter Citation2017). Other Australian bird extinctions occurred well before recent taxonomic reviews that recognised them as valid taxa – ‘dark extinctions’ (Boehm and Cronk Citation2021). This is notably so for the highly fragmented populations of grasswrens formerly included within the historically poorly defined Amytornis textilis – A. modestus complex. Many of these isolates have recently been redefined or recognised as distinct species or subspecies, including the extinct MacDonnell Ranges Thick-billed Grasswren A. modestus modestus (Black et al. Citation2010), the extinct Eastern Thick-billed Grasswren A. m. inexpectatus, the extinct Murchison Western Grasswren A. textilis giganturus and the extinct Large-tailed Western Grasswren A. t. macrourus. The Cape Range Rufous Grasswren has also been recognised recently as a distinct subspecies, after its possible extinction (Black et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, an enigmatic population of Amytornis striatus from the Strzelecki Desert may also represent an undescribed subspecies; however, it has not been recorded for many years and the only two specimens are apparently lost (Black et al. Citation2020): it sits in a limbo of uncertain existence and taxonomy. Earlier recognition of these now extinct taxa as distinct may have prompted more and more timely concern for their conservation, although for at least the grasswrens, remoteness probably also influenced the lack of conservation attention.

Causes of Australian bird extinctions

The pathway and causes of some extinctions are clearcut; others are enigmatic with little available evidence for some species, and likely multiple interacting threats for others. However, in general, the main factors that caused extinctions of Australian birds are those that have led to most extinctions globally (Szabo et al. Citation2012; Doherty et al. Citation2016; Lees et al. Citation2022) – introduced species, hunting, and habitat loss and degradation (). Hunting (for food) was the major cause of at least eight of the Australian bird extinctions, particularly in the early years after colonisation. The impact of hunting was especially pronounced on island endemic species as many of the affected birds were predator-naive, flightless, and had small population sizes – and were sufficiently large to provide a substantial enough food resource to encourage hunting. Subsequently, most of the extinctions of island endemic birds were due to predation by introduced Black Rats, especially so on Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands. Habitat loss and degradation, especially due to livestock and introduced European Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus, contributed to most extinctions of mainland birds, although many of these also involved multiple factors, including predation by Cats Felis catus and European Red Foxes Vulpes vulpes, and changed fire regimes.

The relative impacts of threats contributing to Australian bird extinctions is likely to continue to change, with the impacts of climate change increasing, manifest in part with an increasing incidence of severe wildfires (Legge et al. Citation2022) and ongoing losses of habitat that is susceptible to climate change, notably high elevation rainforest habitats in the wet tropics and subtropics.

Characteristics of Australia’s extinct birds

Extinctions have fallen unevenly across the Australian bird fauna. As noted above, island species are over-represented in the extinctions. But there are also inconsistencies in this pattern of island extinctions. The set of six bird species and five subspecies endemic to Christmas Island (135 km2) have all persisted notwithstanding the introduction of Black Rats, cats and a snake that caused the extinction of an endemic mammal and reptile (Woinarski Citation2018; Emery et al. Citation2021). Endemic taxa of island thrush, fantail, morepork and gerygone have persisted on some oceanic islands but not others with comparable threat regimes: e.g. loss of the island thrush subspecies Turdus poliocephalus poliocephalus and T. p. vinitinctus from Norfolk and Lord Howe Islands respectively, but retention of T. p. erythropleurus on Christmas Island; loss of Rhipidura fuliginosa cervina from Lord Howe, but retention of R. albiscapa pelzelni on Norfolk; loss of Ninox novaeseelandiae albaria from Lord Howe but retention (just) of N. n. undulata on Norfolk; loss of Gerygone insularis from Lord Howe, but retention of G. modesta on Norfolk. In each of these examples, retention has been on the larger/largest island, although other factors may also have contributed to these differences in outcomes.

Unsurprisingly, flightless terrestrial birds have suffered disproportionately high losses (of the nine Australian extinct bird species, three were flightless (two emus and the White Gallinule), leaving only two extant flightless terrestrial species). Extinctions have occurred across a large range of bird sizes from gerygones (ca. 10 g) to emus, across a diversity of dietary types and for birds in many different habitats. However, there have not yet been any extinctions of birds occurring predominantly in rainforests or temperate eucalypt forests, or of birds that migrate to and from Australia. Some large Australian bird families have had no extinctions (e.g. Meliphagidae, with 76 species); in contrast, three of the five Australian taxa in the family Casuariidae are now extinct.

Values of extinct Australian birds

All species have some value and arguably a right to exist. It is challenging to assess the value of now extinct Australian birds. Most had small ranges, so probably had local and minor ecological significance. Tasmanian Emus probably had important cultural values for Indigenous Australians, and probably provided important resources; they may also have had ecological significance as dispersers of some plant species. The Paradise Parrot was an iconic species, highly prized for aviculture, and widely recognised for its beauty. Its imperilment catalysed some of Australia’s first targeted conservation efforts (Chisholm Citation1922) and its ultimate extinction may have sparked a broad public recognition of the tragedy of extinctions more generally and the importance of trying to prevent them (Olsen Citation2007).

Comparisons and context

The starkest contrast for contextualising the Australian bird extinctions is the far greater loss of Australian mammals since 1788. Whereas nine Australian bird species (1.2% of the Australian bird species) have become extinct, of which only one occurred on mainland Australia, 33 Australian mammal species have become extinct (about 10% of the complement of the Australian terrestrial mammal fauna of 325 species (312 on the mainland) at 1788), with 27 of these formerly occurring on the Australian mainland (Woinarski et al. Citation2015, Citation2019). In addition, many of the now extinct Australian mammals had vast ranges, in contrast to the relatively restricted former distributions of now extinct Australian birds. As with birds, extinctions have occurred at a far higher rate for mammal species endemic to Australian islands (six of 13 species: 46%) than for those occurring on the Australian mainland (27 of 312 species: 9%). Whereas the extinctions of Australian mammals have led to the loss of two genera and two families, the Australian bird extinctions were all of species in multi-species genera, such that the Australian bird extinctions have not resulted in higher levels of phylogenetic loss.

The proportion of extinctions in Australian birds is comparable to that for Australian frogs (four species; 1.8% of the Australian frog fauna) and greater than that for reptiles (one species, an island endemic, representing about 0.1% of the Australian terrestrial reptile fauna) (Chapple et al. Citation2019; Woinarski et al. Citation2019), although we note that the rates of extinctions of frogs and reptiles may be under-estimates, given the incomplete taxonomic resolution of these groups in Australia.

The nine Australian bird species extinctions comprise about 5% of the ca. 190 extinctions of bird species globally since 1500 (Lees et al. Citation2022). As for the Australian bird extinctions, island birds are disproportionately represented in these global bird extinctions, comprising 80–90% of all bird species extinctions (Szabo et al. Citation2012; Lees et al. Citation2022). The number of mainland Australian bird species extinctions falls within the range of those on other continents since 1500 (zero for Antarctica and Africa, one each for Asia and Europe, three for South America, and six for North America: IUCN Red List, as at January 2023).

The total number of extinctions of Australian bird species is appreciably less than those of New Zealand (17 species) over the same period, notwithstanding the far smaller pool of species in New Zealand. This may be because New Zealand suffered the introductions of a larger number of species that had impacts on its native birds, because many New Zealand birds had small ranges, and because New Zealand birds had evolved traits over a long period of isolation that made them particularly susceptible to introduced predators (flightlessness, low reproductive output).

The rate of Australian bird species extinctions (9 extinctions from a complement of 753 species, over a 235-year period) equates to 50.9 species extinctions per million species-years (and 54.3 for the period 1900–2023). This represents a much higher rate than the global historical ‘background’ rate of 2 bird species extinctions per million species-years (Ceballos et al. Citation2015), but falls between two recent estimates of current global bird extinctions: 47.5 species extinctions per million species-years by Ceballos et al. (Citation2015) for the period 1900 to 2015, and 132 species extinctions per million species-years for the period 1900 to 2018 by Humphreys et al. (Citation2019), with the variation in these global estimates due largely to different methods of calculation.

Prospective bird extinctions

Many extant Australian birds are now highly imperilled and continuing to decline (Bayraktarov et al. Citation2021; Garnett and Baker Citation2021). Some, such as the suite of bird species (including Victoria’s Riflebird Lophorina victoriae, Bower’s Shrike-thrush Colluricincla boweri, Mountain Thornbill Acanthiza katherina and Fernwren Oreoscopus gutturalis) associated with high elevation rainforests in the Wet Tropics, face threats that are escalating in extent or intensity, and for which no effective controls are yet established (Williams et al. Citation2021). Long-standing habitat fragmentation is imposing an extinction debt for many species by creating discontinuous and non-viable populations. Accordingly, it is likely that there will be more extinctions of Australian bird species in the near future. Two recent studies have used expert elicitation to predict the likelihood of extinctions of Australian bird taxa over the next ca. 20 years, based on assumption of continuation of current management efforts. Geyle et al. (Citation2018) reported that there was a greater than 50% chance of extinction in the next 20 years for four bird species and five bird subspecies, with highest likelihood of loss for King Island Brown Thornbill Acanthiza pusilla archibaldi (94% likelihood), Orange-bellied Parrot (87%), King Island Scrubtit Acanthornis magna greeniana (83%), Western Ground Parrot (75%), Houtman Abrolhos Painted Buttonquail Turnix varius scintillans (71%), Plains-wanderer Pedionomys torquatus (64%) and Regent Honeyeater (57%). Based on these estimates, that study predicted that 10 bird taxa would become extinct over the period 2018–2038, a substantial increase in the rate of Australian bird extinctions experienced to date (average rate of loss of 1.3 bird taxa per decade). Happily, although we are now 25% through the future period considered in that forecast, none of these taxa have yet become extinct, with this result possibly due to increased conservation effort for some of these imperilled taxa. A subsequent assessment using comparable approaches (Garnett et al. Citation2022) was somewhat more optimistic, predicting that only two bird taxa had a > 50% likelihood of extinction over the next 20 years, the Mukarrthippi Grasswren Amytornis striatus striatus and Western Ground Parrot. However, continued rapid declines of many bird taxa (Bayraktarov et al. Citation2021; Garnett and Baker Citation2021) and local extirpations of taxa currently listed as Least Concern (Bennett et al. Citation2024) also suggest the risk of further extinctions remains high.

Priorities to reduce risks of further extinctions

Knowledge of Australian birds and their threats has advanced rapidly in recent decades (Garnett et al. Citation2018), such that the evidence base for conservation prioritisation and action is now generally well established. Nonetheless, there are some important knowledge gaps that may jeopardise attempts to prevent further bird extinctions. For example, there remains much uncertainty about the persistence (and abundance, threats and distribution) of several highly imperilled birds, notably including the Tiwi Hooded Robin, Cape Range Rufous Grasswren, Coxen’s Fig-parrot and Buff-breasted Button-quail. These taxa may slip, or may have already slipped, obscurely into extinction. Their status and conservation requirements need to be clarified, and appropriate and targeted management actions implemented if they are found to be still extant.

Many threats that are causing bird decline (and hence driving taxa towards extinction) remain challenging to control, and their management may require substantial resourcing over many decades (Fraser et al. Citation2022). Such long-term management planning and commitment is generally not consistent with current short-term funding processes. In addition, the quantum of funding, including from government, needs to be substantially increased in order to stave off further extinctions (Wintle et al. Citation2019).

One key foundational component required to attempt to reduce the likelihood of further loss is a commitment by governments, and an expectation by the community, that further extinctions will be prevented. Such a commitment (‘towards zero extinctions’) has been given recently by the Australian government (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2022), with an accompanying strategic approach to that objective.

Another component to reduce the risk of future extinctions of Australian birds is to identify those at most risk, and prioritise these for conservation investment. The degree of imperilment of Australian birds has been the subject of regular review (Garnett and Crowley Citation2000; Garnett et al. Citation2011), with a recent review providing a comprehensive assessment of risks of extinction for all Australian bird taxa (Garnett and Baker Citation2021). This vulnerability assessment has been further quantified through expert elicitation of the likelihood of extinction given existing management (Geyle et al. Citation2018; Garnett et al. Citation2022), and that evaluation provides the basis for prioritising conservation efforts to those taxa at most risk of extinction. The Australian government also included extinction risk as one of the criteria for prioritising species for conservation investment in its recent Threatened Species Action Plan (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2022).

Environmental legislation is also a necessary foundation for the prevention of extinction. Australia’s current legislation, the EPBC Act, has demonstrably failed to prevent extinctions (Woinarski et al. Citation2017) and has many shortcomings (Samuel Citation2020). One of the most notable is its failure to constrain land clearing, resulting in major losses of habitat for threatened species in recent decades (Ward et al. Citation2019). Collectively with states and territories, this failure needs to be remedied through legislative change, with such change currently being designed nationally (DCCEEW Citation2022). The EPBC Act is also deficient in its failure to deal with cumulative threats, to protect critical habitat for imperilled species (Fitzsimons Citation2020), and for not mandating funding and implementation of recovery actions for threatened species.

Islands are key sites for biodiversity conservation in Australia, and globally. Most Australian bird extinctions have been from islands, and many of the most imperilled birds occur only on islands. Accordingly, islands should be prioritised for conservation attention – and some have been so prioritised in the Australian government’s Threatened Species Action Plan (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2022). The recent eradications of introduced mammal pests from Macquarie, Lord Howe and Dirk Hartog Islands have resulted in major conservation gains and secured the future of many highly imperilled bird species. Comparable eradications from other islands supporting imperilled endemic birds (e.g. Christmas, Norfolk) would do much to safeguard those species. Islands with significant biodiversity assets also require better biosecurity, to prevent further introductions of pests and diseases.

Some conservation challenges remain daunting. The most pervasive of these is global climate change, which is likely to ratchet up the pressures and threats on many highly imperilled birds. One of the most susceptible groups is the set of birds associated with high elevation rainforest habitats in the Wet Tropics, whose range and abundance is now shrinking rapidly (Williams et al. Citation2021). Conservation options for such species are very limited, but the current population trajectory for these species is dire, and trial management actions (where possible including translocations) are justified and urgent. Of course, even more important than responding to the potential casualties of climate change is the need for governments and our society to take urgent and more effective measures to tackle the root causes of climate change.

Conservation successes: prevented bird extinctions

A package of conservation measures has been implemented over the last ca. 20–30 years to help prevent extinctions of Australian biodiversity. These measures include national environmental legislation, the development of an extensive conservation reserve system, targeted conservation management actions (notably including eradication of introduced pests from some islands), and research to identify threats and direct the actions that can mitigate those threats. Many threatened bird species have benefited from these actions (Garnett et al. Citation2018): in some cases, such as the Orange-bellied Parrot Neophema chrysogaster and Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix, these actions have led to population increase after many decades of decline, and have averted otherwise likely extinction (Bolam et al. Citation2021). Other Australian birds that would likely now be extinct were it not for sustained, targeted conservation management actions include Western Ground Parrot Pezoporus wallicus flaviventris, Norfolk Island Green Parrot Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae cookii and Norfolk Island Morepork Ninox novaeseelandiae undulata. However, in other cases, conservation actions have had far less success, leading instead to no more than stabilisation or minor reduction in the rates of decline, and improvements in status may take many decades of sustained intensive management (Fraser et al. Citation2022). In many cases, constraints on available funding for conservation management have meant that actions needed to prevent extinction have not been implemented, or implemented only partially (Wintle et al. Citation2019).

Recovering extinct birds

Extinctions are irreversible, but there is some scope and rationale for translocating closely related taxa to (parts of) the range of now extinct bird taxa. These surrogates may help replicate or re-establish any ecological function (‘re-wilding’) or cultural value formerly provided by the now extinct taxon. Such introductions are likely to succeed if and only if the factor(s) that led to the initial extinction are now effectively controlled; or, possibly, if related taxa are introduced from a source population that has adapted or evolved to the threat. One recent proposal has been for trial introductions of the mainland subspecies of Emu Dromaius novaehollandiae novaehollandiae to Tasmania to ‘replace’ the now extinct Tasmanian subspecies Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis (Derham et al. Citation2022), and such introductions are likely to succeed, given that the principal factor causing the initial extinction (hunting) is now controlled.

The eradication of introduced rodents from Lord Howe Island in 2021 (Lord Howe Island Rodent Eradication Project Citation2022) also offers prospects for the introduction of related taxa to act as ecological surrogates for extinct taxa, to help re-assemble the island’s original bird fauna (Hutton et al. Citation2007). Closely related subspecies are potentially available for introduction to replace the Lord Howe Metallic Pigeon Columba vitiensis godmanae and the Lord Howe Red-fronted Parakeet Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae subflavescens (both rendered extinct by mainly hunting, now controlled), the Lord Howe Fantail Rhipidura fuliginosa cervina and Lord Howe Thrush Turdus poliocephalus vinitinctus (both rendered extinct by rats) and the Lord Howe Morepork Ninox novaeseelandiae albaria (Hutton et al. Citation2007). For Lord Howe’s extinct bird species (rather than subspecies), options are more challenging: the Lord Howe Gerygone Gerygone insularis may be replaceable by a related species (feasibly Norfolk Island Gerygone Gerygone modesta), but there is no plausible surrogate for the White Gallinule.

Although there may be some prospects for resurrection of some extinct species through genetic reconstruction from specimens, this is unlikely to be plausible for extinct Australian birds in the foreseeable future, due to major technical challenges. There are also profound ethical concerns with de-extinction, including that its (yet unrealised) hope may lead to less community concern about extinction, and that the major investments required could more usefully be directed to saving imperilled species (Banks and Hochuli Citation2017; Waterhouse and Mitchell Citation2022).

Discussion

Concern about the fate of Australian birds is long-standing. Noting major declines for many bird species, and the ongoing spread of some threats, several observers in the early twentieth century predicted the imminent extinction of many bird species from continental Australia (North Citation1901; Campbell Citation1915; Ashby Citation1924a, Citation1924b). Happily, these predictions have not (yet) been realised. Indeed, the most striking feature of Australian bird extinctions is that only one species has been lost from mainland Australia notwithstanding the near pervasive extent of many threats and the broad-scale environmental transformation and degradation that has been the legacy of European colonisation of Australia. Given this array of changes and threats, the bird fauna of continental Australia has proven – so far – to be remarkably resilient, and especially so in comparison to the high rates of extinction experienced by Australian mammals (Woinarski et al. Citation2015, Citation2019). The anomaly may not be so much for birds, but rather be mostly in the exceptional rate of mammal loss, which is probably due to the extreme susceptibility of many Australian mammal species to two introduced predator species, the cat and fox (Legge et al. Citation2018; Radford et al. Citation2018). Australian bird species have proven to be less vulnerable to these introduced predators, although many have suffered major declines and are now threatened (e.g. Malleefowl Leipoa ocellata and Night Parrot Pezoporus occidentalis). Although we should be grateful for the limited loss of Australia’s mainland bird species, we should not be complacent about the risks of extinction: many mainland bird species are now Critically Endangered, continuing to decline and at high risk of extinction in the near future.

In contrast to the low rate of extinctions of birds on the Australian mainland, 38% of the bird species that were endemic to Australia’s islands (smaller than Tasmania) are now extinct. The susceptibility of island endemic species is a global characteristic, driven largely by their typically small population size, limited genetic diversity, low reproductive output, predator naivety, and – for some bird species – flightlessness. In some cases, the extinction of Australian island endemic birds happened remarkably quickly following the introduction of predators. For example, the Robust White-eye Zosterops strenuus was common on Lord Howe Island up to 1913, but became extinct by 1928, due to predation by Black Rats accidentally introduced in 1918 (McAllan et al. Citation2004). Such cases serve as a warning that extinctions can occur very quickly.

What do extinctions matter? The basis of this article is that extinctions are undesirable and we should strive to prevent further extinctions. Extinctions subvert inter-generational equity – the principle that we should pass on to our descendants a world that is as wonderful, diverse and healthy as that we have inherited. As ornithologists, and more generally, we deeply regret that we now have no opportunity to see the beautiful Paradise Parrot or the quirky White Gallinule. We should not rob our children of the opportunity to see what exists now. Extinctions also are indicators that we are not living sustainably, that we have distorted and degraded the ecosystems on which we too depend. Less selfishly, there is an argument that all species have a right to exist, and that it is improper for us to impinge on that right. For, in some form or other, all the extinctions documented here are due to what we have done, or not done, to this country. We can, and must, do better.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barry Baker, Rob Davis and two anonymous referees for valuable commentary on a previous draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data used in this paper are in the public domain in fully-cited documents.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashby, E. (1924a). Notes on extinct or rare Australian birds, with suggestions as to some of the causes of their disappearance. Part I. Emu - Austral Ornithology 23(3), 178–183. doi:10.1071/MU923178

- Ashby, E. (1924b). Notes on extinct or rare Australian birds, with suggestions as to some of the causes of their disappearance. Part II. Emu - Austral Ornithology 23(4), 294–298. doi:10.1071/MU923294

- Banks, P. B., and Hochuli, D. F. (2017). Extinction, de-extinction and conservation: A dangerous mix of ideas. The Australian Zoologist 38(3), 390–394. doi:10.7882/AZ.2016.012

- Bayraktarov, E., Ehmke, G., Tulloch, A. I. T., Chauvenet, A. L., Avery-Gomm, S., McRae, L., et al. (2021). A threatened species index for Australian birds. Conservation Science and Practice 3, e322. doi:10.1111/csp2.322

- Bennett, A. F., Haslem, A., Garnett, S. T., Loyn, R. H., Woinarski, J. C. Z., and Ehmke, G. (2024). Declining but not (yet) threatened: A challenge for avian conservation in Australia. Emu 124, 123–145. doi:10.1080/01584197.2023.2270568

- Bergstrom, D. M., Wienecke, B. C., van den Hoff, J., Hughes, L., Lindenmayer, D. B., Ainsworth, T. D., et al. (2021). Combating ecosystem collapse from the tropics to the Antarctic. Global Change Biology 27, 1692–1703. doi:10.1111/gcb.15539

- Black, A., Dolman, G., Wilson, C. A., Campbell, C. D., Pedler, L., and Joseph, L. (2020). A taxonomic revision of the striated Grasswren Amytornis striatus complex (Aves: Maluridae) after analysis of phylogenetic and phenotypic data. Emu-Austral Ornithology 120, 191–200. doi:10.1080/01584197.2020.1776622

- Black, A. B., Joseph, L., Pedler, L. P., and Anf Carpenter, G. A. (2010). A taxonomic framework for interpreting evolution within the Amytornis textilis-modestus complex of grasswrens. Emu-Austral Ornithology 110, 358–363. doi:10.1071/MU10045

- Boehm, M. M. A., and Cronk, Q. C. B. (2021). Dark extinction: The problem of unknown historical extinctions. Biology Letters 17, 20210007. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2021.0007

- Bolam, F. C., Mair, L., Angelico, M., Brooks, T. M., Burgman, M., Hermes, C., et al. (2021). How many bird and mammal extinctions has recent conservation action prevented? Conservation Letters 14, e12762. doi:10.1111/conl.12762

- Bowman, D., Williamson, G. J., Yebra, M., Lizundia-Lolola, J., Pettinari, M. L., Shah, S., et al. (2020). Wildfires: Australia needs a national monitoring agency. Nature 584, 188–191. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-02306-4

- Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2012). Little left to lose: Deforestation and forest degradation in Australia since European colonization. Journal of Plant Ecology 5(1), 109–120. doi:10.1093/jpe/rtr038

- Campbell, A. J. (1915). Missing birds. Emu - Austral Ornithology 14(3), 167–168. doi:10.1071/MU914167

- Carpenter, G. (2017). ‘The Spotted Quail-Thrush in the Mount Lofty Ranges, South Australia, with Results of a Survey in 2016.’ (Natural Resources Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges: Adelaide.)

- Ceballos, G., Ehrlich, P. R., Barnosky, A. D., García, A., Pringle, R. M., and Palmer, T. M. (2015). Accelerated modern human–induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Science Advances 1(5), e1400253. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400253

- Chapple, D. G., Tingley, R., Mitchell, N. J., Macdonald, S. L., Keogh, J. S., Shea, G. M., et al. (2019). ‘The Action Plan for Australian Lizards and Snakes 2017.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne.)

- Chisholm, A. H. (1922). The “lost” paradise parrot. Emu - Austral Ornithology 22(1), 4–17. doi:10.1071/MU922004

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2022). ‘2022-2032 Threatened Species Action Plan: Towards Zero Extinctions.’ (Department of Climate Change Energy the Environment and Water: Canberra.)

- DCCEEW. (2022). ‘Nature Positive Plan: Better for the Environment, Better for Business.’ (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water: Canberra.)

- Derham, T., Johnson, C., Martin, B., Ryeland, J., Ondei, S., Fielding, M., and Brook, B. W. (2022). Extinction of the Tasmanian Emu and opportunities for rewilding. Global Ecology and Conservation 41, e02358. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02358

- Doherty, T. S., Glen, A. S., Nimmo, D. G., Ritchie, E. G., and Dickman, C. R. (2016). Invasive predators and global biodiversity loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, 11261–11265. doi:10.1073/pnas.1602480113

- Emery, J.-P., Mitchell, N. J., Cogger, H., Agius, J., Andrew, P., Arnall, S., et al. (2021). The lost lizards of Christmas Island: A retrospective assessment of factors driving the collapse of a native reptile community. Conservation Science and Practice 3, e358. doi:10.1111/csp2.358

- Fitzsimons, J. A. (2020). Urgent need to use and reform critical habitat listing in Australian legislation in response to the extensive 2019–2020 bushfires. Environmental and Planning Law Journal 37, 143–152.

- Fraser, H., Legge, S. M., Garnett, S. T., Geyle, H., Silcock, J., Nou, T., et al. (2022). Application of expert elicitation to estimate population trajectories for species prioritized in Australia’s first threatened species strategy. Biological Conservation 274, 109731. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109731

- Garnett, S. T., and Baker, G. B. (Eds.). 2021. ‘Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne.)

- Garnett, S. T., Butchart, S. H. M., Baker, G. B., Bayraktarov, E., Buchanan, K., Burbidge, A. A., et al. (2018). Metrics of progress in the understanding and management of threats to Australian birds. Conservation Biology 33, 456–468. doi:10.1111/cobi.13220

- Garnett, S. T., and Crowley, G. M. (2000). ‘The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000.’ (Environment Australia: Canberra.)

- Garnett, S. T., Hayward-Brown, B. K., Kopf, R. K., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Cameron, K. A., Chapple, D. G. et al. (2022). Australia’s most imperilled vertebrates. Biological Conservation 270, 109561. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109561

- Garnett, S. T., Latch, P., Lindenmayer, D. B., and Woinarski, J. C. Z. (Eds.). 2018. ‘Recovering Australian Threatened Species: A Book of Hope.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Clayton.)

- Garnett, S. T., Szabo, J. K., and Dutson, G. (2011). ‘The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2010.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Collingwood.)

- Geyle, H. M., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Baker, G. B., Dickman, C. R., Dutson, G., Fisher, D. O., et al. (2018). Quantifying extinction risk and forecasting the number of impending Australian bird and mammal extinctions. Pacific Conservation Biology 24, 157–167. doi:10.1071/PC18006

- Holdaway, R. N., and Anderson, A. (2001). Avifauna from the Emily Bay settlement site, Norfolk Island: A preliminary account. Records of the Australian Museum 53, 85–100. doi:10.3853/j.0812-7387.27.2001.1343

- Humphreys, A. M., Govaerts, R., Ficinski, S. Z., Nic Lughadha, E., and Vorontsova, M. S. (2019). Global dataset shows geography and life form predict modern plant extinction and rediscovery. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3(7), 1043–1047. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0906-2

- Hutton, I., Parkes, J. P., and Sinclair, A. R. E. (2007). Reassembling island ecosystems: The case of Lord Howe Island. Animal Conservation 10(1), 22–29. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00077.x

- Keith, D. A., Butchart, S. H. M., Regan, H. M., Harrison, I., Akçakaya, H. R., Solow, A. R., and Burgman, M. A. (2017). Inferring extinctions I: A structured method using information on threats. Biological Conservation 214, 320–327. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.026

- Kingsford, R. T., Bino, G., and Porter, J. L. (2017). Continental impacts of water development on waterbirds, contrasting two Australian river basins: Global implications for sustainable water use. Global Change Biology 23(11), 4958–4969. doi:10.1111/gcb.13743

- Lees, A. C., Haskell, L., Allinson, T., Bezeng, S. B., Burfield, I. J., Renjifo, L. M., et al. (2022). State of the world’s birds. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 47, 231–260. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-112420-014642

- Legge, S., Murphy, B. P., McGregor, H., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Augusteyn, J., Ballard, G., et al. (2017). Enumerating a continental-scale threat: How many feral cats are in Australia? Biological Conservation 206, 293–303. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.032

- Legge, S. M., Rumpff, L., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Whiterod, N. S., Ward, M., Southwell, D. G., et al. (2022). The conservation impacts of ecological disturbance: Time-bound estimates of population loss and recovery for fauna affected by the 2019–2020 Australian megafires. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31, 2085–2104. doi:10.1111/geb.13473

- Legge, S. M., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Burbidge, A. A., Palmer, A., Ringma, J., Radford, J., et al. (2018). Havens for threatened Australian mammals: The contributions of fenced areas and offshore islands to protecting mammal species that are susceptible to introduced predators. Wildlife Research 45, 627–644. doi:10.1071/WR17172

- Lombal, A. J., Salis, A. T., Mitchell, K. J., Tennyson, A. J. D., Shepherd, L. D., Worthy, T. H., et al. (2020). Using ancient DNA to quantify losses of genetic and species diversity in seabirds: A case study of Pterodroma petrels from a Pacific island. Biodiversity and Conservation 29, 2361–2375. doi:10.1007/s10531-020-01978-8

- Lord Howe Island Rodent Eradication Project. (2022). https://lhirodenteradicationproject.org/ [Verified 10 June 2023].

- McAllan, I. A. W., Curtis, B. R., Hutton, I., and Cooper, R. M. (2004). The birds of the Lord Howe Island group: A review of records. Australian Field Ornithology 21, 1–82.

- Morton, S. R., Stafford Smith, D. M., Dickman, C. R., Dunkerley, D. L., Friedel, M. H., McAllister, R. R. J., et al. (2011). A fresh framework for the ecology of arid Australia. Journal of Arid Environments 75(4), 313–329. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.11.001

- Murray, P. F., and Vickers-Rich, P. (2004). ‘Magnificent Mihirungs: The Colossal Flightless Birds of the Australian Dreamtime.’ (Indiana University Press: Bloomington.)

- Nolan, R. H., Bowman, D. M. J. S., Clarke, H., Haynes, K., Ooi, M. K. J., Price, O. F., et al. (2021). What do the Australian Black summer fires signify for the global fire crisis? Fire 4, 97. doi:10.3390/fire4040097

- North, A. J. (1901). The destruction of native birds in New South Wales. Records of the Australian Museum 4(1), 17–21. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.4.1901.1078

- Olsen, P. (2007). ‘Glimpses of Paradise: The Quest for the Beautiful Parakeet.’ (National Library of Australia: Canberra.)

- Radford, J. Q., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Legge, S., Baseler, M., Bentley, J., Burbidge, A. A., et al. (2018). Degrees of population-level susceptibility of Australian mammal species to predation by the introduced red fox Vulpes vulpes and feral cat Felis catus. Wildlife Research 45, 645–657. doi:10.1071/WR18008

- Samuel, G. (2020). Final report of the independent review of the environment protection and biodiversity conservation act 1999. Australian Government, Canberra.

- Schodde, R., and Mason, I. J. (1999). ‘The Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne.)

- Szabo, J. K., Khwaja, N., Garnett, S. T., and Butchart, S. H. M. (2012). Global patterns and drivers of avian extinctions at the species and subspecies level. PLoS ONE 7, e47080. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047080

- Thompson, C. J., Koshkina, V., Burgman, M. A., Butchart, S. H. M., and Stone, L. (2017). Inferring extinctions II: A practical, iterative model based on records and surveys. Biological Conservation 214, 328–335. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.029

- van Grouw, H., and Hume, J. P. (2016). The history and morphology of Lord Howe Gallinule or Swamphen Porphyrio albus (Rallidae). Bulletin of the British Ornithological Club 136, 172–198.

- Ward, M. S., Simmonds, J. S., Reside, A. E., Watson, J. E. M., Rhodes, J. R., Possingham, H. P., et al. (2019). Lots of loss with little scrutiny: The attrition of habitat critical for threatened species in Australia. Conservation Science and Practice 1, e117. doi:10.1111/csp2.117

- Ward, M., Watson, J. E. M., Possingham, H. P., Garnett, S. T., Maron, M., Rhodes, J. R., et al. (2022). Creating past habitat maps to quantify local extirpation of Australian threatened birds. Environmental Research Letters 17, 024032. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac4f8b

- Waterhouse, J., and Mitchell, C. (2022). ‘Has anybody seen a Tasmanian Tiger lately?’: Ethical and ontological considerations of thylacine de-extinction. Green Letters 26(1), 14–27. doi:10.1080/14688417.2021.2006741

- Williams, S. E., de la Fuente, A., and Martínez-Yrízar, A. (2021). Long-term changes in populations of rainforest birds in the Australia wet tropics bioregion: A climate-driven biodiversity emergency. PLoS ONE 16(12), e0254307. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254307

- Wintle, B. A., Cadenhead, N. C. R., Morgain, R. A., Legge, S. M., Bekessy, S. A., Possingham, H. P., et al. (2019). Spending to save: What will it cost to halt Australia’s extinction crisis? Conservation Letters 12, e12682. doi:10.1111/conl.12682

- Woinarski, J. (2018). ‘A Bat’s End: The Christmas Island Pipistrelle and Extinction in Australia.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne.) doi:10.1071/9781486308644

- Woinarski, J. C. Z. (2019). Killing Peter to save Paul: An ethical and ecological basis for evaluating whether a native species should be culled for the conservation benefit of another native species. The Australian Zoologist 40(1), 49–62. doi:10.7882/AZ.2018.020

- Woinarski, J. C. Z., Braby, M. F., Burbidge, A. A., Coates, D., Garnett, S. T., Fensham, R. J., et al. (2019). Reading the black book: The number, timing, distribution and causes of listed extinctions in Australia. Biological Conservation 239, 108261. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108261

- Woinarski, J. C. Z., Burbidge, A. A., and Harrison, P. L. (2015). The ongoing unravelling of a continental fauna: Decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 4531–4540. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417301112

- Woinarski, J. C. Z., Garnett, S. T., Legge, S. M., and Lindenmayer, D. B. (2017). The contribution of policy, law, management, research, and advocacy failings to the recent extinctions of three Australian vertebrate species. Conservation Biology 31, 13–23. doi:10.1111/cobi.12852

- Worthy, T. H., and Nguyen, J. M. T. (2020). An annotated checklist of the fossil birds of Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 144, 66–108. doi:10.1080/03721426.2020.1756560