Abstract

We interviewed 20 adolescents who were coercively placed in residential or psychiatric care. The aim was to explore their views on the way staff relate and perform their duties, favorable characteristics in staff, consequences of different treatment from staff and their safety experiences. Thematic analysis identified the following themes: Situational triggers of frustration; Care-based; rule-based; or passive-avoidant interaction styles toward adolescents and their responses; Adolescents’ reflections about staff’s interaction styles; and the Consequences on the unit atmosphere depending on different interaction styles toward the adolescents. Adolescents preferred staff who showed them respect and a clear wish to make life easier.

Introduction

In Sweden, which has 10 million inhabitants, around 1,500 adolescents per year are involuntarily admitted to residential care institutions organized by The Swedish National Board of Institutional Care (SiS) or to psychiatric inpatient wards organized by the public health care system (SiS, Citation2019; SKL, Citation2019).

Adolescents who are coercively admitted to care constitute a particularly vulnerable population, since there is a risk that institutional care will be ineffective or, that there are better alternatives, or that the intervention may even be harmful to a child’s mental health (Barter, Citation2003; Ståhlberg et al., Citation2017).

The principal ethical question is whether the effects of the intervention are advantageous enough to justify being taken into custody. It is therefore problematic that the scientific knowledge about the effects of coercive care is so scarce (De Swart et al., Citation2012; Ståhlberg et al., Citation2017).

The decision to involuntarily place children or adolescents in an institution is connected with a great societal responsibility which by extension means defending the best interests of the child and protecting them from harmful environments. It is essential that the institutional environments do not cause further harm (Attar-Schwartz & Khoury-Kassabri, Citation2015; UNICEF, Citation1989).

Another important ethical issue concerns the child’s right to participate “in all matters affecting the child” (UNICEF, Citation1989). In coercive care, the patient’s input is even more specified by law, whereby a treatment plan should be made with the patient as soon as possible after admittance. This is based on the ethical principle that involvement in treatment is especially important during coercive care when the patient is not free to leave the hospital.

Violence in its many different forms is common in institutions for coercive care (Attar-Schwartz & Khoury-Kassabri, Citation2015; Davidson-Arad & Golan, Citation2007), where many adolescents have problems with aggression, criminality, and drug use (Hage et al., Citation2009; Winstanley & Hales, Citation2008). The occurrence of violence between peers (Khoury-Kassabri & Attar-Schwartz, Citation2014), and violence from adolescents toward staff is a common occurrence. This gives rise to high rates of workplace-related sickness and traumatic experiences (Berg et al., Citation2013; Ryan et al., Citation2008). There have also been reports of violence from staff toward adolescents (Barter, Citation2003), which raises specific ethical concerns.

Previous research on violence in institutions for children and adolescents has primarily focused on frequencies of different forms of violence and on individual and social risk factors for violence, but less on institutional risk factors (Hage et al., Citation2009). Results from an early meta-analysis (Shirk & Karver, Citation2003), suggest that the quality of the staff-adolescent relationship is an important factor associated with the treatment outcome, but only a few studies have investigated the staff–adolescent relationship from the adolescents’ perspective (Henriksen et al., Citation2008; Ungar & Ikeda, Citation2017). There is also a paucity of studies concerning desirable characteristics or virtues in staff. The research area is dominated by reports in which the adolescents’ experiences of staff are quite negative, but some exceptions can be found, where some studies have provided more positive reports of staff.

An example of a critical perception of staff is given in a report by Sekol (Citation2013), where adolescents often expressed that staff ignored their problems, commonly made humiliating or intimidating comments, and sometimes even used violence to control or punish. Some adolescents held the view that both staff and adolescents were frustrated to a level at which violence was easily triggered.

Conversely, Gibbs and Sinclair (Citation2000) interviewed 233 adolescents in residential children’s homes about bullying and sexual harassment, which was found to be quite common among peers. However, their view of staff was generally positive, and they described good overall relationships. In another study (Ungar & Ikeda, Citation2017), adolescents in residential care were asked about their relationships with staff. The authors identified three different kinds of staff roles. The first group was labeled “informal supporters,” which was characterized by a nonhierarchical structure, clear human aspects of their professional role, few rules, and an emphasis on empathy. The second group was labeled “the administrators,” which included staff who based their work on rules that were “in the best interest of the child,” equality, fairness, and based on a low level of emotional involvement. The third group was labeled “the caregivers”, which included staff who had realistic expectations, emphasized upholding distinct structures at the institution, and showed a high level of flexibility in negotiations with the adolescents when rules had been broken. The “informal supporters” were most appreciated by the adolescents.

In a Swedish study, 46 girls and boys were asked how they perceived the personal commitment of their key staff during their placement in residential treatment centers. The qualitative analysis resulted in the following three categories: “negative personal involvement,” “instrumental personal involvement,” and “positive personal involvement.” According to these adolescents, the obstacles that hindered a positive relationship with staff were a lack of trust, the use of collective punishment, and a lack of staff continuity (Henriksen et al., Citation2008). To our knowledge, these are the only studies that specifically investigated desirable characteristics and virtues in staff. There is thus an obvious lack of studies with a more ethical perspective. This is an issue given that institutional care of children and adolescents is accompanied by many ethical responsibilities and obligations from society, which should aim to help people grow in an important phase of life.

An ethical perspective on this issue needs to be based on the fact that the relation between the adolescent and staff is asymmetrical power. This type of power has been called dispositional power since both parties are aware of it, whether executed or not (Scott, Citation2008). This asymmetric relationship alone is a valid reason to demand high ethical awareness in institutional staff, especially when it comes to situations where violence is about to occur or has just occurred. All staff members therefore have a responsibility regarding how relationships with adolescents are formed, which greatly influences the adolescent’s perception of whether s/he perceives him/herself as a subject in an inter-subjective meeting (Engström, Citation2008; Pelto-Piri et al., Citation2014), or as an object in routine-based care.

The ethical values that staff explicitly or implicitly show adolescents can be viewed on three levels. The first level focuses on the action or deed itself, where the central question is which alternative for the action staff choose and for what reasons. It is also a question of what constitutes a just or unjust behavior. The second level focuses on the moral agent as it is expressed by the way staff relates to the adolescent. This level focuses on the characteristics and virtues that adolescents generally prefer in the institution, and more specifically in potentially violent situations. The third level focuses on the interpersonal relationship between staff and adolescents.

The aim of this study was to explore how adolescents coercively placed in residential or psychiatric care view the way members of staff relate and perform their duties. We were particularly interested in which staff characteristics that they feel are most favorable and how they experienced the consequences of different treatment from staff. The adolescents’ experiences of safety in potentially violent environments were also explored.

Materials and methods

The present study is part of the research program Prevention of Violence in Inpatient Care: Aspects of Ethics and Safety in Encounters with Patients. The program includes studies of violence and aggression in general; forensic, addictive, and child and adolescent psychiatric services; and residential institutions for youth in Sweden (Hylen et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Pelto-Piri et al., Citation2019).

Design

We used a qualitative approach because it enables an inside perspective and promotes a deeper understanding of the meaning of the experiences of adolescents living in the coercive ward milieu. The qualitative analysis was guided by principles for using thematic analysis in psychology (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). We used a theoretical approach, which means that our specific research interests (i.e., the adolescents’ view of communication and social interaction patterns with staff, and experiences regarding the ward milieu) guided the coding of the interview text. Furthermore, we decided to use the realist method to report the reality as it was experienced by the adolescents, and to search for a deeper meaning of that reality from their perspective by identifying recurrent patterns of meaning in the interviews (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Ethical considerations

According to the Swedish Ethical Review Act (Swedish Statute Book [SFS], Citation2003, p. 460), this research project was examined by the Regional Ethical Committee in Uppsala, Sweden (2014/112). Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary, and that they could withdraw at any time without giving any reason. If participants were younger than 15 years, their guardians were informed about the study and given the opportunity to refuse the participation of their child. To assure secrecy in this report, no name, sex, or age is stated in quotes from the interviews.

Recruitment of participants

Eligible participants were adolescents taken into coercive care and placed in two Swedish state-run residential homes (one for girls and one for boys) or in one child and adolescent psychiatry unit (for both sexes). Participants were selected by purposive sampling (Tong et al., Citation2007) to provide rich and varied data that included a variety of cases (i.e., both sexes, a variety of ages, and those placed in coercive care under different acts). Residential care for young persons with psychosocial problems, substance abuse, or criminal behavior is given under the terms of the Care of Young Persons Act or the Secure Youth Care Act; coercive care in child and adolescent psychiatry is given under the terms of the Involuntary Psychiatric Care Act.

The inclusion criteria for this study were (a) girls and boys between 13 and 19 years of age, (b) had been receiving coercive care for at least 2 weeks prior to the research interview, (c) were able to speak and understand Swedish, and (d) were willing to take part in a ∼30-minute interview on one occasion about their experiences of being in coercive care.

The director of each chosen facility was informed about the study. S/he informed the adolescents in his/her facility about the aim of the study, gave them oral and written information, and asked for their participation in a research interview. A total of 21 adolescents from three facilities gave their written consent to participate in the study. One girl withdrew her consent, leaving a final total of 20 adolescents (13 girls and 7 boys) with a median age of 17 years (13–19 years). They had at least 3 weeks’ experience of coercive care before the interview.

Interviews

The interviews covered the adolescents’ perceptions of the following key topics: experiences of being placed in coercive care, adolescent–staff and adolescent–adolescent communication and interactions, values experienced in the ward, staff characteristics and virtues, and safety experiences in threatening or violent situations. Two of the authors (K.E. and T.S.) conducted all the interviews (ten interviews each). Only the participant and one of the interviewers (K.E. or T.S.) were present during the interviews, which were conducted in a secluded room at the treatment centers. The interviews lasted for about half an hour (20–90 minutes) and were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant.

Data analysis

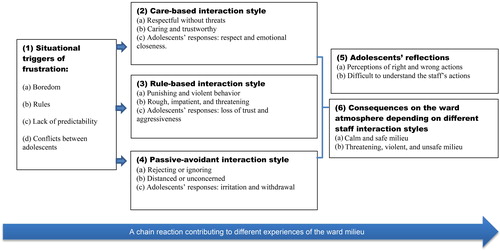

The thematic analysis involved six steps, as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The steps were: becoming acquainted with the material by reading through the text, initial coding, looking for themes by clustering related codes together, revising themes, describing and naming themes, and finally, developing a text. The term “theme” is used as a way to identify important elements from the interviews in relation to the overall research questions that together capture the adolescents’ experiences in the coercive ward milieu. This does not necessarily mean the most common statements across the dataset. To reach a consensus in the analysis, the two interviewing authors independently listened to all the recorded interviews and compared the transcripts with the audiotaped interviews to check correctness. The texts were then read several times to acquire an overall impression of the material. All text related to the aim were marked individually by the two authors (K.E. and T.S., i.e., these were the interviewers). The next steps included rereading and coding, and identifying patterns and nuances clustered together in subthemes. The two authors (K.E. and T.S.) then assessed the participants’ statements in relation to the themes to ensure confirmability of the results (i.e., neutrality with findings based on participants reports) (Shenton, Citation2004). All authors discussed the results of the analysis until agreement was reached, and then sorted the subthemes and chosen statements into themes. At a descriptive semantic level, the analysis resulted in four themes (see ). By using interpretative analysis, the authors developed two latent themes (themes five and six; see ); in an attempt to interpret the adolescents’ underlying ideas about the staff’s ethical values and the consequences of the staff’s actions.

Results

The adolescents’ stories revealed both positive and negative daily life experiences. The analysis revealed how different events were linked in a chain of events, which started when the adolescents were deprived of their freedom. This stressful event triggered an emotional reaction, which staff responded to in different ways. Depending on how staff chose to respond to the adolescents, positive or negative behavioral patterns were initiated that affected the consequent interaction patterns and thereby gave rise to the adolescents’ experiences.

The thematic analysis revealed six themes. The themes contained pathways that all contributed to the adolescents’ experiences of the ward milieu and were as follows: (1) Situational triggers of frustration, (2) Care-based interaction style (3) Rule-based interaction style, (4) Passive-avoidant interaction style (5) Adolescents’ reflections, and (6) Consequences on the ward atmosphere depending on different staff interaction styles. The themes in relation to the chain of events are illustrated in .

Situational triggers of frustration

The first theme concern triggers of frustration in the situation or milieu. The participants described the negative feelings generated when being locked up in coercive care. These included feelings of losing everything outside the ward and even losing a part of their own personality. These early experiences were reported to lead to death wishes, aggression, and protests. Nuances identified within this theme were as follows: (a) Boredom, (b) Rules, (c) Lack of predictability, and (d) Conflicts between adolescents.

Boredom

After arriving at the ward, some adolescents soon felt bored with concurrent experiences of excessive energy levels. Central contributing factors were being forced to stay indoors most of the time and a lack of physical activity. These situational triggers generated an irritable or bad mood, and the adolescents expressed a need for the company of an adult or for other adolescents that could lighten their mood. The following is a quote from one participant who described the feelings experienced when arriving at the coercive care unit:

So, at the start, my whole life was turned upside down. It was, like, I felt so bad. I just wanted to die then. It was brutal. It was really tough. But it took like a week and then it was like the other people who live here too—you become pals with them. You get to know the other people who are in the same situation as yourself, so it gets, you know,—they make the situation better …//… I had a hell of a lot of energy and thought it was quite fun, mucking about with everyone. I didn’t know, I, I don’t know what to do. You have … you get … you gather a lot of energy, you know, when you’re not doing anything. We don’t move around much in here.

In the following two quotes, the participant describes feelings of irritation, aggression, and discomfort at being placed in a locked unit, and their resulting reactions to these feelings:

It’s like you get easily irritated because you know it’s locked; you can’t get out. So, everything you do is indoors apart from sport. Absolutely everything else is indoors. So, no, you can be sitting with a member of staff and he doesn’t say anything, you know? He sits there, really bored and doesn’t do anything. Stuff like that, you know. Doesn’t talk with you, doesn’t joke with you. And everything you say to him, he speaks bluntly and so on. Then you don’t feel so good. It’s easy to get angry too. You get irritated with that person. If there’s a member of staff that can joke with you, that understands you, and stuff like that, then you’re more likely to feel better.

It’s because people are new at the most locked unit and, most of the time, they haven’t got used to it. In a way you’re here … but you don’t accept it. You need to accept you’re here. You can make changes. It’s like … I don’t believe it, then it’s like, what the hell am I doing here? I’m really angry, hitting out at anyone. I don’t care. But after a while, I got used to it.

Many adolescents expressed the need to align emotionally with staff members, who were often emotionally unavailable to them. However, after some time at the ward, clear signs of resignation were expressed, whereby adolescents felt a necessity to accept the situation.

Rules

When adolescents arrived at the unit, they were informed about the institutional rules about smoking, phones, time-schedules, and behavior toward staff and other adolescents. Adolescents felt that there was an excessive number of rules that were illogical or unfair, which generated high levels of frustration and aggression. In some of the units, one such rule was no smoking, while smoking was permitted in other adjacent units within the same institution. This rule meant an abrupt smoking cessation for some adolescents. This abstinence, together with stress related to the initiation of coercive care, generated a lot of agitation and aggression. The adolescents emphasized the calming effect of smoking on their aggression levels, and how the irregular distribution of substitute nicotine pills also triggered frustration.

Smoking bans. I don’t think they’re necessary. I think it’s just here and one other place that’s got a smoking ban. I mean especially when you’re over 18 or have got permission from your parents—so I think four cigarettes a day should be taken as a given. You can be really highly strung when everything’s really new. So especially at the start, it would be really good (to be able to smoke).

Another rule that was hard for the adolescents to understand was that activities such as baking were not permitted, which would have increased their enjoyment and well-being at the unit.

Yepp, it’s like they don’t want you to have fun here. It’s like it should be really boring, eh? It really is. Umm, it’s like, they, as well as you yourself, say that you shouldn’t want to be here. So they try to make it so that you want to get away from here as fast as possible so that nobody likes it or wants to stay. But it’s really hard for those who have a compulsory order and really don’t want to be here, it’s a really boring environment so you want to get away from here even more than you didn’t want to be here in the very beginning.

Lack of predictability

Adolescents described a lack of understanding about the purpose of their involuntary institutional placement and lacked insight regarding what was expected of them to be discharged from care. Many informants worried about what the upcoming decision might mean for their future and felt sadness or anger about having little opportunity to influence these decisions. They reported that their stay felt like a long and uncertain wait, whereby they suffered from a lack of predictability.

You never know. You don’t get the schedule telling you you’ll be moved or anything. But you’ve got to sleep and you’ve got to get up. Some days are good but it’s boring when you’re waiting. It’s the days when you’re waiting. You don’t know when it will end and you can get out.

I have a meeting with my social worker today and she’s really vague about why I’m here. I get angry and sad about it, because I want a clear explanation about why I’m here; because I’ve no reason to be here. I’m just waiting it out, so it’s like sitting in prison waiting for your punishment to end. I don’t know what I’ve done. Like, there’s no reason for me being here … I get confused when I don’t get to know things, when I don’t know what’s happening. Yeah.

Conflicts between adolescents

The grouping of adolescents placed together in one unit, seemed to be an important milieu factor. If a group was chaotic, all adolescents were affected in some way, even if they tried to stay out of trouble. Some reported feeling insecure since they were afraid of some of their peers, who had sometimes committed violent crimes. Others got involved in fights due to provocation or mutual bad behavior that escalated to the level of aggression. Some tried to gain respect by frightening their peers, which can occur as a result of a lack of self-confidence, while others tried to keep away from conflicts.

It comes and goes in sort of circles with people being replaced all the time. Sometimes a rowdy group comes and then it’s a group like this one now. So now it’s really nice and I’m moving on Friday, so I’m ending with a lovely group, and that’s nice, instead of me maybe coming in, not wanting to quarrel or anything and coming into a rowdy group where it’s just chaos all the time and maybe affecting me too.

Yesterday was hellish for me. Someone who’s living here came up and said: “Your ex has got it together with my pal.” Yes, but don’t tell me that. It has an effect on me. I don’t want to have anything to do with that person—but it still affects me.

If I’m honest, it was maybe insecurity. I was insecure and felt I needed to prove myself to avoid people messing with me. You understand? My insecurity came from me not wanting folks to mess with me.

Another challenge in the everyday life of the adolescents was relating to and interacting with staff and their diverse working styles. In the following themes (two to five) the participants describe their experiences of the ward, including staff characteristics and actions in their encounters with adolescents, as well as the adolescents’ responses to the staff’s various interaction styles.

Care-based interaction style

In the second theme, the adolescents described staff that basically care for the adolescents in coercive care, thereby showed signs that they wanted to make life easier for the adolescents under troubled circumstances. They also described preferable characteristics in staff concerning how staff relate to the adolescents or take a caring interaction style even in threatening or violent situations. This theme also covers how the adolescents responded to this style. To describe the theme in more detail, we sub-grouped it into (a) respectful without threats, (b) caring and trustworthy, and (c) adolescents’ responses: respect and emotional closeness.

Respectful without threats

This group of staff met the adolescents in a respectful and sensitive manner. They gave attention to those who were sad and comforted them with emotional closeness. They adjusted the rules according to the individual and the situation, for example, by having confidence in a well-behaving adolescent. These care-based staffs were active and could handle the situational frustrations generated upon the arrival of an adolescent. They also prevented aggressive or violent situations in a caring way. In brief, they focused on creating a good relationship with the adolescent.

They show more that they care. They seem to like their job and they fit in here. They kind of know. They’re calm and patient. They pep you up. But the others are more like … umm … they just sort of work. That’s what they do … My favorite people talk to me; the others just stare at me when I’m eating.

He’s respectful. It’s like, if I’m not feeling good, he comes and comforts me.

If the adolescents were agitated or unwilling to follow the rules, these staff could shift focus away from a troubled situation by talking kindly to them, setting limits without threats of punishments, or just take a walk with the adolescent instead of confronting them. This kind of staff member was appreciated by the adolescents. The following quote describes an example of how a staff member shifted focus from a conflict to a solution without using any threats:

It’s better to go away and talk … So … me and one of the staff quarreled and I shoved the staff member. Then a female staff member wanted me to go away with her to talk so we got to go out for a spell, to a filling station, and bought something to drink and stuff and had a ciggie. So we walked and talked. So when we went in, we’d resolved it. It was, like, over and done with. By instead … or, for example, going out and sitting down to chat or walking and talking. Just in general, instead of threatening us with something.

Caring staff also gave the adolescents an opportunity to influence decisions, as shown in the following quote:

Yes, we get to be involved, have our say, and make suggestions, and then the staff will come to an agreement on how it can be resolved. So they try to do everything to ensure we get to do what we want to do.

Caring and trustworthy

The adolescents described several positive characteristics in care-based staff, such as being kind, thoughtful, and caring. Staff with their own experience of a troublesome childhood was especially valued because adolescents felt that they had a unique ability to truly understand them. Care-oriented staff was also perceived as authentic, which meant that they could be spontaneous, relaxed, and playful, which is a characteristic that was much appreciated.

They’re happy and play FIFA with us and chill out and play ping-pong and all that. It is important! When we get together, they’re like friends … not staff who work here … so they become friends with us…

They’re not so rigid, you know? They’re not so severe and things like that—so you can joke with them, we can have fun, we can chat; know what I mean? They can be serious and not so serious.

Adolescents’ responses: Respect and emotional closeness

In these relationships, the adolescents expressed how they chose to be loyal and respectful toward care-oriented staff, as well as keeping calm and avoiding fights. Even if they were planning an escape, they avoided implementing the plan during the shifts of the care-oriented staff to protect them from criticism. The adolescents showed emotional closeness to staff who gave them emotional closeness.

She’s more like … how would I put it … a mother figure—and we learn a lot from her. She understands. Instead of threatening us with things, she talks, discusses, and mulls things over and stuff like that, you know? So then we reach a solution. It’s cool … instead of just saying no. I’ve always had respect for her, but I always clash with Stephan.

Had it been a certain member of staff working that night, we probably wouldn’t have escaped—because we wouldn’t want to get them into trouble or anything like that.

To summarize, this second theme illustrates a mutual respect and understanding between adolescents and care-based staff. These staff had a flexible approach toward rules and strived to create opportunities for adolescents to be involved. A care-based interaction style was perceived by the adolescents as desirable, since they felt totally dependent on the staff and without anyone else to turn to.

Rule-based interaction style

This interaction style was described by the adolescents as staff having a “guard-like style”, with a focus on obeying the rules. Staff with this style was described as emotionally distant and were reported to use verbal threats of punishments as well as physical compulsion or violence. They acted immediately and roughly, and were ready to punish adolescents before explaining why. These kinds of staff members required respect from the adolescents before showing respect back. We sub-grouped this theme into (a) punishing and violent behavior, (b) rough, impatient, and threatening, and (c) adolescents’ responses: loss of trust and aggressiveness.

Punishing and violent behavior

In situations where adolescents did not obey the rules, this group of staff was ready to punish. They demanded and forced obedience, and acted violently toward the adolescents. If the adolescents behaved in the same violent way, they ended up in isolation. Some adolescents told stories of how staff sometimes misunderstood a request and interpreted it as a threat, and this even resulted in an adolescent being wrestled to the floor.

Well, one time I didn’t want to go into my room. And then, I don’t know … there was something that happened in any case. Then four of the staff pulled me down to the floor and crossed my legs like this. I was lying on my stomach and they crossed my legs over and pulled them up toward my back. And my arms, just like this. I lay like that down on the ground and then they took me into isolation.

There were several similar examples of staff behaviors that the adolescents considered excessively violent.

The thing is, they grip you so hard that it’s sore. They, like, twist your arm behind you like a police grip so the whole of your arm feels it’ll be twisted out of joint. And I say: “Take it easy!” I scream to them. It’s painful. They don’t listen.

One adolescent also wondered why staff did not adjust their interventions and take the previous trauma of the adolescent into account, as in the following example of a young girl who had previously been gang raped by men:

So, they just pulled her and tried to get her out of my room even though she refused … I screamed: “Just let her go! She’s only 12. She can’t deal with this.” Because I know she’s also been sexually abused. And, … then they went into her—just guys—and she just couldn’t handle that at all. She screamed and cried. There were four or five male members of staff on her and she’d, like, already been sexually abused by a gang. And the staff knew that.

For all stories of violence from these staff, adolescents reported that there was silence afterwards; there was no reflection about what happened and no consideration about why or how they felt afterwards.

Rough, impatient, and threatening

This group of staff were described as rough and impatient, and tried to stop all unwanted behavior. This also happened in situations of adolescents’ playful teasing, nagging, or unwillingness to directly obey. These staffs were felt to be threatening if obedience to the rules was not immediately shown. This was often experienced by the adolescents as an overreaction or a lack of respect.

There wasn’t a fight. It was mostly bickering, yeah. One youth who had been home bickered with another who was acting up a little at the table, the kitchen table. And one of them says: “Shut your mouth!”—or something cocky like that—and the other says exactly the same thing. One of the staff comes and says: “Be quiet at once! The first to continue will go into isolation!” Then it was like exactly how it gets—you get extra angry when you hear that kind of thing.

There are lots of rules here you’ve got to stick to and they don’t understand us and they don’t even try to understand us. They don’t show us any respect and they complain that we don’t show them any respect. And they like … don’t care.

Adolescents’ responses: Loss of trust and aggressiveness

If adolescents experience rule-based staff, their respect for staff may disappear, and the level of anger or hate may increase. Some adolescents reported that their experience with rule-based staff meant that they lost their trust in people with positions of power, and that this is something they believe will continue to affect them when they return to society. The adolescents described situations in which staff clearly had the opportunity to choose a respectful behavior, but instead chose to ensure obedience through violence. The adolescents were surprised that this type of staff believed that their violent methods would lead to respectful and calm behavior in adolescents.

… it was a unit manager … I’m alcohol dependent, umm … so I’d got hold of a bottle of hand sanitizer and was going to drink it, so she took it off me and I went totally crazy and started throwing chairs over the table. She grabbed me and just twisted my whole arm so there was a big bruise all over it. It’s like they just grab us and we get injured. I understand they’re scared when we run away and do something stupid and obviously they’re trying to help us in some way, but it doesn’t help to calm us by doing this. We panic even more and get more aggressive and fight them even more if they grab us. That’s what doesn’t really add up.

… I usually say to them that it’s obvious which ones have been security guards and which ones haven’t. That’s what I usually say. Those who are security guards—who work as security guards or work here, they’re always going around like this—on show … and asserting themselves. And it becomes a bit hard because most of us don’t like guards here. And they try to act tough, so then there will be conflict between the young people and them.

A summary of this third theme is that the adolescents perceived some staff to be rule-based, to use threats and punishments, and sometimes to even be violent. The adolescents had no opportunity to discuss a solution when the staff acted quickly and decisively in a way that was perceived as provocative, which also led to the escalation of a conflict. The adolescents were thus easily drawn into aggressive behaviors and lost respect for the adults who behaved in this way.

Passive-avoidant interaction style

In this theme, participants described how some of the staff used a passive or sometimes avoidant interaction style toward the adolescents. This was evident in all kind of situations, from everyday activities to suddenly threatening situations due to violence or deterioration of a psychiatric condition. We sub-grouped this theme into (a) rejecting or ignoring, (b) distanced or unconcerned, and (c) adolescents’ responses: irritation and withdrawal.

Rejecting or ignoring

In situations where adolescents suffered from severe anxiety, self-harm, or suicide attempts, staff with a passive-avoidant interaction style trivialized or ignored the severity of the condition, pretended not to see, and left them alone. The following quote illustrates a lack of support during severe anxiety:

Some of them don’t care. It’s like one evening when the night staff were working, I sat in my room having an anxiety attack and crying a hell of a lot. Then one of the staff comes in and says: “I’ll close your door so that you don’t disturb the other patients.” Then she shut the door and I sat there crying all by myself.

The adolescents reported that this kind of staff often said no without explaining why. In sudden violent situations, they did not intervene or protect the adolescents, but waited for other staff to solve the situation and protected themselves. The following quote describes another example of this passive style:

Their safety is more important than ours. It’s like, umm … some of the young people get to have their own walks for half an hour around four times a week where they get to walk in the forest area by themselves for half an hour—but if another of the young ones, who doesn’t get to do this, asks to go for a walk in the same forest area with one of the staff they say: “No, we don’t know what might happen and we wouldn’t dare go there.” But still they let many of the young ones go out on their own. Just recently, there’s been a gang of guys and a man on his own who usually hang around here chatting with the young people and yeah … behaving badly. They don’t care about us; they just care about themselves.

Several other examples showed how staff were passive in threatening situations; for example, they hid in an office behind locked doors or left arguing adolescents to solve the threatening situation by themselves.

When one of the staff … he’d been sitting with us … went away from there, someone went for me. They didn’t start hitting me but said lots of nasty stuff and stuck their arms out like this as if they were going to attack me or something like that. I stood there. So, I was scared inside but I still stood there.

Distanced or unconcerned

The staff with this interaction style behaved as if they did not care about the adolescents, and this was felt to be callous. During everyday activities, these staff showed silence, inactiveness, or disapproval. This disinterest in the adolescents and their problems was experienced as a complete lack of caring for them.

and then there are the others who’re very different from the other ones. Detached and just doing their job, you know? Just doing what they have to do, going home, sleeping, and not giving a shit about us, coming back and doing what they have to do, you know?

Adolescents’ responses: Irritation and withdrawal

This passive or avoidant interaction style triggered irritation, and adolescents responded by withdrawn behavior that was dominated by spending a lot of time alone in their room. Others reacted negatively and lost respect toward staff that ignored serious symptoms or the adolescents’ needs. These staff left the adolescents with a sense of abandonment and the feeling that they were insignificant or alone in their struggle.

I’ve completely lost respect for all the staff because they tell me that when I cut myself, it’s just silly. When I feel bad and have panic anxiety attacks, it’s just silly too. It’s just something I make up. It’s just something I do because I want to go to YPU.Footnote1 I hate YPU! YPU is the worst place, the last place I would go to if I was going somewhere. And they don’t get it. They think I’m like playing some bloody role-play with them!

A summary of this fourth theme is that some staff were described as uninvolved and distanced. In emotionally difficult situations, the adolescents felt abandoned by the adults, who did not seem to respond to their needs and instead withdrew. The adolescents easily lost respect for these kinds of staff members, which led to either increased aggression or withdrawal.

Adolescents’ reflections

In the fifth theme, the adolescents reflected on the staff’s different interaction styles, which they understood as by staff freely chosen ways of acting to fulfill their duties at work. The adolescents tended to judge the actions of staff as either right or wrong, depending on whether the result of their actions generated a desirable mood or not. They also discussed reasons behind the different interaction styles used by staff. The theme is described in two subthemes that capture (a) perceptions of right and wrong actions and (b) difficult to understand the staff’s actions.

Perceptions of right and wrong actions

This sub-theme captures a range of experiences, from respectful interactions to openly offensive behavior. The respectful behavior is judged to be right if it involves “give-and-take”. The staff needed to win the adolescent’s trust before they could expect any respect back. This was described by adolescents as being listened to, believed in, and taken seriously.

So almost all the staff I met in this unit are like… cozy, and they open up. They are not so stiff, so. And I think it’s good. So, not that they are so boring because then we may not think it is as fun. We hang out with the staff very much and the manager too, she is great.

If reciprocity was missing, contradictions arose. Some adolescents reflected on what rights the staff actually had, and how they themselves might have acted in a similar situation.

I get angry because I don’t think you should … I think you can be involved the whole time. I think that’s what you should do. I don’t think you can hop in and do your own thing just when it, like, suits you. I think that’s wrong—so I get angry.

The adolescents could admit that rules and some compulsion are needed in specific situations, but they questioned why some staff used these so often and even to the point of painful violence. They also stressed how some staff humiliated the adolescents by using violence, even if the situation did not require it. These kinds of situations are judged as an abuse of power. In conclusion, if an action by the staff caused pain or was offensive, adolescents judged it as wrong.

Difficult to understand the staff’s actions

Some of the staff were considered to be highly suitable for their job, and the adolescents saw that they wanted to make things better for them. These staffs were described as those who made efforts to create a respectful and understanding interpersonal relationship with the adolescents.

No, she’s understanding. For example, when I was staying in solitary about a week ago, she was there and could sit there all day, sitting and chatting and we discussed things, we had a bit of fun even though I was in solitary. And it’s not so often you feel good in there.

Those who exhibited abusive behavior seemed to regard their job as simply a way to get an income. The latter group was judged by the adolescents as unsuitable for a job dealing with other people, as described in the following quote:

They shouldn’t be there because they don’t care about the young people, just about getting a wage.

Some ways staff was interacting with the adolescents were found to be impossible for them to understand at all. A clear example of this is that some adolescents were left by themselves after showing self-mutilating behaviors; adolescents considered this to be highly inappropriate. Another situation in which the adolescents could not understand the staff’s actions was when the staff chose to close the door on an adolescent who had just tried to end his/her life. According to the adolescents, the staff members should have stayed to give comfort and consolation. To conclude, in this theme, the adolescents reflected upon right and wrong actions by the staff. They also reflected on what qualities or virtues they preferred to see in staff.

Consequences on the ward atmosphere depending on different staff interaction styles

The adolescents considered the staff’s different interaction styles to have positive or negative influences on the ward milieu. The consequences of staff interaction styles are described in two subthemes that capture a (a) calm and safe milieu and (b) threatening, violent, and unsafe milieu.

Calm and safe milieu

In general, the adolescents most appreciated staff who were care-based, since they calmly solved problematic situations through conversations rather that threats, and thereby kept the atmosphere calm. The adolescents reported that creating a relaxed atmosphere meant that staff and adolescents could enjoy spending time together doing different activities or just relaxing together.

The care-based interaction style was found to result in a milieu that was perceived as both calm and safe. The styles and methods used by staff lightened the mood and created a good atmosphere, in which the adolescents could find pleasant “time-killers” in a friendly milieu. Some described this kind of milieu as if they were a family caring for each other. Others understood and appreciated the ambitions of the staff to make the milieu calm and for it to feel like a home, but stated that a coercive care unit can never become as safe or cozy as a home.

Yes, you can joke with them a bit more, so it’s becoming more fun in the unit. It makes it a nicer stay on the unit for everyone if all the staff are nice and are, like, in a good mood when they come here every morning.

Instead, you become like a big family … yeah, we’ve been together with each other. And we have a really nice time with the staff. Sitting and snuggling on the couch. So it’s lovely, massage times, stuff like that. Everybody pleating each other’s hair and stuff.

Threatening, violent, and unsafe milieu

The adolescents reported that interaction styles that could be described as rule-based, negatively affected the atmosphere of the units. As a result of threats or violence from the staff, the level of aggression increased among the adolescents, and they even reported feeling hatred after feeling disrespected or insulted. In these cases, the adolescents sometimes hit back to defend themselves, since the staff had supposedly started the violent acts in the first place. The stories of the adolescents revealed that, when the staff acted like guards, this enhanced conflicts between adolescents and staff and created a barrier to forming relationships with emotional depth. Some adolescents chose to step back and avoid conflicts with staff.

A passive-avoidant interaction style shown by staff clearly increased levels of stress, irritation, and distress. This style created a milieu that was characterized by feelings of fear and general insecurity, when the adolescents were left alone to solve threatening situations or were mistrusted and left by themselves when experiencing high levels of anxiety or severe suicidal behavior.

So, um, I tried to hang myself from a door handle one time … they came in and checked on me and then went away. Um … it sounds really weird. Other times, since then, they, like, said to me: “Knock it off or else we’ll press the alarm.”/…/They just went away/…/It feels, it feels good for me but I think it’s weird. I wouldn’t have done that./I probably would have watched over that person.

In this theme, the adolescent perceived the environment and atmosphere in the unit as a direct consequence of the staff’s interaction styles. The adolescents were surprised at how staff did not seem to understand how their styles of interaction had an impact on the experiences of either a safe, or a violent and threatening milieu.

Discussion

One of the main goals of this study was to explore adolescents–staff relationship factors in coercive youth care from the perspectives of the adolescents. Learning from the adolescents’ experiences can help create a safe and calm ward milieu.

The adolescents’ statements about appreciated or disliked staff characteristics and interaction styles suggest that the staff responded to the adolescents in one of three identified interaction styles. The first style, most appreciated by the adolescents, was when staff used the “care-based interaction style,” which was characterized as respectful, trustworthy, and caring. The second style, strongly criticized by the adolescents, was the “rule-based interaction style,” whereby staff concentrated on orderliness and demanded immediate obedience by using threats, punishments, or violence. The third style was the “passive-avoidant interaction style,” whereby the adolescents felt that the staff distanced themselves through a passive response or simply by ignoring them. The two latter styles increased the adolescents’ level of aggression and feelings of distrust toward adults.

Some aspects of our findings are similar to those of Ungar and Ikeda (Citation2017). They identified three different styles of staff response patterns toward adolescents as follows: “Informal supporters,” with empathy and few rules; “formal administrators,” who emphasize rules but do so with low emotional engagement; and “workers as a caregiver substitute” with realistic expectations and a flexible attitude toward rule breaking adolescents. The adolescents in our study, as well as those in the one by Ungar and Ikeda (Citation2017), most appreciated staff members who acted more like friends and who placed a focus on personal relationships and intimacy rather than on punitive consequences. Our findings are also in line with Hill (Citation2005), who described a pretended alliance between staff and adolescents when staff focused on obeying the rules. The findings of distrust toward staff have also been described by Henriksen et al. (Citation2008), who found that a negative client–staff relationship was characterized by lacking mutual exchange and an absence of positive emotional depth. These relationships created a lack of trust and a negative attitude toward staff, which left adolescents with the sense that staff were distant. Staff with a passive-avoidant interaction style, as reported by the adolescents in our study, can also be found in other studies. For example, Peterson-Badali and Koegl (Citation2002) described passive staff as “turning a blind eye”; when staff chose to look the other way so as not to be involved in a conflict. Sekol (Citation2013) describes this as “ignorance,” and it can be interpreted as a lack of commitment, which is common, according to Berg et al. (Citation2011).

Coercive care involves various situations that can create frustration. The adolescents in our study described how a lack of activities, rules that were difficult to understand, and uncertainty about the present and future trigged escalating levels of frustration. The adolescents’ emphasized a need to be met by staff in a caring, friendly, and guiding manner to avoid further frustration. The adolescents reported that if feelings of frustration were not addressed pedagogically by staff with a discussion of solutions, the frustrations often escalated to threats or violence. This was especially the case, if staff acted decisively or ignorantly toward the adolescents. These results are in line with those of Berg and coauthors (Berg et al., Citation2011), who emphasized the importance of staff staying calm and talking to adolescents in a supportive way to prevent aggressive situations. The adolescents in our study thus understood the mechanisms behind a safe or violent care milieu, as a logical result of a chain of events that affect the care milieu in a positive or negative way. In the opinion of these adolescents, the chain of events that led to a violent milieu was activated by staff who were focused on obedience rather than on the needs of the adolescent, or by staff who used an ignoring style when responding to the adolescents’ varying moods and frustrations. On the other hand, a calm and safe milieu was the result of a chain of events that was created by the care-based staff when they responded to the adolescents’ mood fluctuations in a kind, thoughtful, and playful way.

The adolescents’ appreciation of the staff’s different interaction styles can be understood at the three ethical levels, focusing on (1) the action itself, (2) the characteristics or virtues of the person acting, and (3) the fundamental view of humanity revealed by the action. At the first ethical level, the adolescents expressed a basic human need, which they expected to be met by the staff in coercive care. That is, to be seen, understood, and treated with respect, without elements of threat or violence. At the second ethical level, adolescents valued staff who could interpret their behavior, which has been emphasized also by others (Berg et al., Citation2011; Sekol, Citation2013). Adolescents also appreciated a willingness to negotiate and co-create solutions. At the third ethical level, our results indicate that adolescents need and value an interaction style that creates supportive relationships with staff that are based on reciprocity and emotional bonding. This need has also been emphasized in other studies, which have suggested that the relationship between staff and adolescents might be the most important predictor of care outcome (Harder et al., Citation2013; ten Brummelaar et al., Citation2018).

Limitations

We have used a qualitative design and thematic analysis with an exploratory nature to describe and interpret the meaning and significance of the adolescents’ experiences in coercive care. However, we only interviewed the adolescents once. This might have given a more critical view of the staff, since earlier interview-studies with repeated interviews found the second interview to give a more positive view of the staff (Henriksen et al., Citation2008). Future work could benefit from using repeated interviews or adopt ethnographic designs to further increase adolescents’ feelings of safety in sharing their experiences on a deeper level during interviews.

Conclusions

Our findings emphasize that the interaction styles adopted by staff in day-to-day communications with adolescents greatly influence the quality of adolescent–staff relationships. A care-based interaction style provides an opportunity to create a safe and calm ward milieu, without threats and violence.

Our research highlights two major lessons that should be learned from the experiences of adolescents in coercive care. Firstly, some staff members act in such a way as to increase adolescents’ aggression levels, which can result in threats and violent behavior from both adolescents and staff. According to the adolescents, seclusion is sometimes used by staff as punishment, which is highly problematic from an ethical point of view. Secondly, staff that are care-based in their interactions try to build relationships based on understanding and mutual respect. These staff members also strive for a participatory way of working within coercive care.

The central ethical issue is how to ensure that coercive treatment of children and adolescents does not give rise to harmful events. In that sense, treatment methods in coercive circumstances should be centered on care-based relationships with staff.

To conclude, this study found that staff interact with adolescents in considerably different ways, and that this has a profound influence on how adolescents perceive the care that is given. Increasing our awareness of these issues could help to improve the quality of care in residential and psychiatric institutions for adolescents.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

No dataset is available.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 1. YPU: Young People’s Units, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

References

- Attar-Schwartz, S., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2015). Indirect and verbal victimization by peers among at-risk youth in residential care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.007

- Barter, C. (2003). Young people in residential care talk about peer violence. Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care, 2(2), 39–50.

- Berg, J., Kaltiala-Heino, R., Löyttyniemi, V., & Välimäki, M. (2013). Staff’s perception of adolescent aggressive behaviour in four European forensic units: A qualitative interview study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 67(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2012.697190

- Berg, J., Kaltiala-Heino, R., & Välimäki, M. (2011). Management of aggressive behaviour among adolescents in forensic units: A four-country perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(9), 776–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01726.x

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Davidson-Arad, B., & Golan, M. (2007). Victimization of juveniles in out-of-home placement: Juvenile corrections facilities. British Journal of Social Work, 37(6), 1007–1025. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcl056

- De Swart, J. J. W., Van den Broek, H., Stams, G. J. J. M., Asscher, J. J., Van der Laan, P. H., Holsbrink-Engels, G. A., & Van der Helm, G. H. P. (2012). The effectiveness of institutional youth care over the past three decades: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(9), 1818–1824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.015

- Engström, K. (2008). Delaktighet under tvång. Om ungdomars erfarenhet i barn- och ungdomspsykiatrisk slutenvård [Participation under coercion. On young people’s experiences in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatient care] [Doctoral dissertation, Örebro universitet, Örebro]. Diva-portal.org

- Gibbs, I., & Sinclair, I. (2000). Bullying, sexual harassment and happiness in residential children’s homes. Child Abuse Review, 9(4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0852(200007/08)9:4<247::AID-CAR619>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Hage, S., Van Meijel, B., Fluttert, F., & Berden, G. F. (2009). Aggressive behaviour in adolescent psychiatric settings: What are risk factors, possible interventions and implications for nursing practice? A literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(7), 661–669. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01454.x

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, E. (2013). A secure base? The adolescent-staff relationship in secure residential youth care. Child & Family Social Work, 18(3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00846.x

- Henriksen, A., Degner, J., & Oscarsson, L. (2008). Youths in coercive residential care: Attitudes towards key staff members’ personal involvement, from a therapeutic alliance perspective. European Journal of Social Work, 11(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450701531976

- Hill, T. (2005). Allians under tvång. Behandlingssamarbete mellan elever och personal på särskilda ungdomshem [Sham alliance: Treatment collaboration between delinquent youth and staff in correctional institutions] [Doctoral dissertation, Linköping, Sweden]. Diva-portal.org

- Hylén, U., Engström, I., Engström, K., Pelto-Piri, V., & Anderzen-Carlsson, A. (2019). Providing good care in the shadow of violence—An interview study with nursing staff and ward managers in psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1496207

- Hylén, U., Kjellin, L., Pelto-Piri, V., & Warg, L. E. (2018). Psychosocial work environment within psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden: Violence, stress, and value incongruence among nursing staff. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(3), 1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12421

- Khoury-Kassabri, M., & Attar-Schwartz, S. (2014). Adolescents’ reports of physical violence by peers in residential care settings: An ecological examination. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(4), 659–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513505208

- Pelto-Piri, V., Engström, K., & Engström, I. (2014). Staffs’ perceptions of the ethical landscape in psychiatric inpatient care: A qualitative content analysis of ethical diaries. Clinical Ethics, 9(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477750914524069

- Pelto-Piri, V., Wallsten, T., Hylén, U., Nikban, I., & Kjellin, L. (2019). Feeling safe or unsafe in psychiatric inpatient care, a hospital-based qualitative interview study with inpatients in Sweden. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0282-y

- Peterson-Badali, M., & Koegl, C. (2002). Juveniles’ experiences of incarceration. The role of correctional staff in peer violence. Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(01)00121-0

- Ryan, E. P., Aaron, J., Burnette, M. L., Warren, J., Burket, R., & Aaron, T. (2008). Emotional responses of staff to assault in a pediatric state hospital. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 36(3), 360–368.

- Scott, J. (2008). Power (Key concepts). Polity Press.

- Sekol, I. (2013). Peer violence in adolescent residential care: A qualitative examination of contextual and peer factors. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(12), 1901–1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.006

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Shirk, S. R., & Karver, M. (2003). Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.452

- SiS. (2019). SiS Årsredovisning 2018 [SiS annual report]. Retrieved December 18, 2019 from https://www.stat-inst.se/globalassets/arsredovisningar/arsredovisning-2018.pdf

- SKL. (2019). Psykiatrin i siffror. Barn- och ungdomspsykiatri – Kartläggning 2018. [Psychiatry in figures 2018. Child and adolescent psychiatry]. Retrieved December 18, 2019 from https://www.uppdragpsykiskhalsa.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/BUP_2019_190701.pdf

- Ståhlberg, O., Boman, S., Robertsson, C., Kerekes, N., Anckarsäter, H., & Nilsson, T. (2017). A 3-year follow-up study of Swedish youths committed to juvenile institutions: Frequent occurrence of criminality and health care use regardless of drug abuse. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 50(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.09.004

- Swedish Statute Book. (2003). The Act concerning the ethical review of research involving humans (2003, p. 460), Sveriges Riksdag.

- ten Brummelaar, M. D. C., Harder, A. T., Kalverboer, M. E., Post, W. J., & Knorth, E. J. (2018). Participation of youth in decision-making procedures during residential care: A narrative review. Child & Family Social Work, 23(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12381

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Ungar, M., & Ikeda, J. (2017). Rules or no rules? Three strategies for engagement with young people in mandated services. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(3), 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0456-2

- UNICEF. (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child; UN General Assembly, Resolution 44/25. Retrieved May 31, 2019 from https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

- Winstanley, S., & Hales, L. (2008). Prevalence of aggression towards residential social workers: Do qualifications and experience make a difference? Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-008-9051-9