Abstract

The main task of mental health care services is to provide good quality of care. Despite this, users are sometimes treated badly by staff. The purpose of this study was to investigate violations and infringements towards users in mental health care services, from the perspectives of both staff and users. Data were gathered through an anonymous online questionnaire sent to staff and users in Norway. Staff were recruited in collaboration with professional organisations and users in collaboration with user-organisations.

Altogether, 1,160 staff and 320 users answered the questionnaires. Over 90% off the staff respondents that had answered the questionnaire had experienced some kind of violation and infringements towards users. Of these, 21% of the staff said they had treated users with disrespect, and 16% reported having behaved condescendingly towards users. Further, 46% of the staff answered positive to the question about having rejected users. Accordingly, 67% of the users in this sample had experienced being treated with disrespect, 63% had experienced being treated with condescension and 59% had experienced rejection while receiving mental health treatment. Violations and infringements seem to be common in mental health treatment, also according to the staff. This study found that mental health care staff also report and acknowledge that some users experience violations and infringements during mental health care. As a consequence, this is to the best of our knowledge, the first study that confirms users’ experiences of inadequate mental health care also from a staff perspective. It is of outmost importance to further assess occurrence of violations and infringement in mental health treatment, both through research and as part of quality assurance programmes.

Background

Health care is based on the four ethical principles: beneficence, do no harm, justice and respect for autonomy (Beauchamp & Childress, Citation2009). Despite this, users frequently report being treated badly by mental health care staff (Staniszewska et al., Citation2019, Whitelock, Citation2009, Galpin & Parker, Citation2007). According to the Norwegian User Safety Committee, users safety is an under-prioritised area in mental health care (UKOM, Citation2020). It is thought-provoking that these reports keep coming, without being taken seriously. This study found that mental health care staff also report and acknowledge that some users experience violations and infringements during mental health care. As a consequence, this is to the best of our knowledge, the first study that confirms users’ experiences of inadequate mental health care also from a staff perspective. It is important for this group of vulnerable users that this issue be further examined through future research into how to safeguard users against violations and infringements.

Descriptions of bad experiences stretch from being treated with disrespect to verbal abuse and physical violence. In 2007, Swedish radio journalists investigated 1.900 mental health care staff and revealed that they had witnessed a great number of humiliations towards users (Bodin & Velasco, Citation2007). Inspired by this investigation, we decided to examine both staff and users’ experience of such phenomena in Norwegian mental health care. Among other factors, power imbalances make users in institutional settings vulnerable and places them at risk for violations and infringements, abuse and neglect. Relational, cognitive and behavioural challenges may also be risk factors for being exposed to violations and infringements.

While questions of abuse and neglect have been investigated in relation to children’s services, services for people with learning disabilities and services for older people (Williams & Keating, Citation2000), there is limited research on these topics in the context of mental health. The most relevant research to date focussed on services for the older people in nursing homes, investigating the three key concepts of violations, abuse and neglect (Malmedal et al., Citation2009b). Fulmer and O’Malley (Citation1987) made no distinction between violations, abuse and neglect, claiming that care of older persons may be judged as either adequate or inadequate (Fulmer & O’Malley, Citation1987). As they see it, abuse and neglect are subsets of violations: “All cases of abuse and neglect can be thought of as violation, defined as the presence of unmet needs for personal care” (p. 21). This definition includes unmet needs for care and supportive relationships, as well as freedom from harassment, threats and violence. This research topic is relatively new, and terminology is not quite developed yet. In some circumstances, the term ‘inadequate care’ refers in a broader sense to ‘treatment failure’. In this study, we have chosen to use the terms ‘violation and infringement’. More specifically the behaviours or experiences we asked about in the questionnaire was if the informants had experienced, performed, witnessed or heard about users being exposed to: rejection, disrespect, lack of privacy, condescending behaviour, neglect, threats, physically rough treatment, verbal harassment, physical violence or ‘shoving, spitting, throwing things’.

Previous studies

There has been some research about patients’ experiences of coercion in Norwegian mental health care (Olofsson & Norberg, Citation2001, Nyttingnes et al., Citation2016, Hem et al., Citation2018a). Other studies have shown that users’ who are voluntarily admitted may experience different kind of humiliations in care, and that not all negative experiences are related to coercion (Husum et al., Citation2019). A search in MEDLINE, using the search words ‘violation’, ‘infringement’ in mental health care; found no articles from mental health care. However, violations and infringements of other vulnerable user groups in institutions, like users with learning disabilities, children and youth, older people and from the field of gynaecology has been documented (Malmedal et al., Citation2009a, Stanley et al., Citation1999). These studies had only data from staff, and non from users. We found however a study about protecting mental health client’s dignity. The study analysed 335 written narratives from 335 clients in mental health care. Of these, 105 persons had experiences humiliation or punishment and 104 persons had experiences rejection during care (Kogstad, Citation2009).

Two related studies in mental health care settings have also been identified. Frueh et al. (Citation2005) examined persons who had been admitted to day-hospital programs in the US and their perceptions of traumatic and harmful incidents during treatment in mental health institutions. Many respondents perceived potentially traumatic incidents during their admission, and had experienced physical violence, sexual humiliations and violations. The study concluded that humiliating, traumatic and potentially harmful incidents occur in the psychiatric setting, and research efforts and clinical work need to devote more attention to these issues (Frueh et al., Citation2005). Svindseth et al. (Citation2007) investigated patients’ feeling of humiliation during the admission process in mental health acute care. In this study, 102 users were interviewed about their experiences 48 hours after admission. The researchers found that both voluntarily and involuntarily admitted users reported having felt humiliated to some degree during the admission process. About half had experienced degrees of humiliation. They talked about being exposed to both verbal and physical force, in addition to feeling that the admission was not right.

Further, a Norwegian national health survey of satisfaction among 1,831 mental health care users, showed that around one third had experienced humiliation to some degree (Bjerkan et al., Citation2009). Around 180 users had felt personally humiliated during their hospitalisations, and 130 users experienced humiliation to the utmost degree. Involuntarily admitted users felt most humiliated, but users who were voluntarily admitted also reported feeling that way, a finding in line with those of previous studies. The study did not elaborate on what kind of experiences may be perceived as humiliating. In another national survey of user experiences in mental health care services about 30% of users reported a feeling of being treated with too little respect or being humiliated during care (Kjøllesdal et al., Citation2017). This is a high percentage, and the topic needs to be further investigated. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to investigate staff and users’ experiences of the mental health care setting. Inspired by the Swedish journalistic investigation (Bodin & Velasco, Citation2007), we asked about what kind of violations and infringements towards users; staff and users had witnessed and experienced during their work or during treatment in the Norwegian mental health care system.

Research questions

What kind of violations and infringements towards users had staff heard about, witnessed or performed during their work in mental health care?

What kind of violations and infringements towards users had users heard about, witnessed or experienced during mental health care?

Methods

Data collection

This study was part of a larger study about ethics, humiliation and use of coercion in mental health care at the Centre for Medical Ethics at the University of Oslo (Aasland et al., Citation2018, Husum et al., Citation2020). The study was a comprehensive study performed in the period of 2011–2016 and involved several data-collections, both qualitative and quantitative. Data presented in this article has not been presented before. Data for this part of the study was collected through an anonymous electronic survey among professionals and treatment staff from all parts of the Norwegian psychiatric and addiction treatment system. In addition, data was collected from persons with experience from treatment in mental health care through collaboration with Norwegian user-organisations. Data collections was conducted in the last part of 2014 and in the beginning of 2015. The questionnaires aimed at health care professionals and people with experiences with treatment was constructed in the same way, to be able to compare data from the two questionnaires.

The staff questionnaire

The online questionnaire aimed at mental health care staff was distributed through the five most relevant professional organisations who invited members who worked in mental health and addiction care to participate using the Questback© platform. These were the Norwegian Medical Association, the Norwegian Psychological Association, the Norwegian Nurses Organisation, the Norwegian Union of Social Workers and the Norwegian Union of Municipal and General Employees that organises nursing assistants. Each organisation sent emails with a link to the electronic questionnaire to those members who, according to their membership registers, worked in relevant mental health settings—a total of 15,576 professionals. Since all answers were anonymous, it was not possible to send individual reminders. The mix of professionals in the sample is fairly representative of the national distribution of multiprofessional staff groups in mental health care in Norway. There was a modest overrepresentation of psychiatrists and social workers and a modest underrepresentation of the other professional groups.

The user questionnaire

An online questionnaire, to be answered anonymously, was disseminated to 2,573 members of the major users’ organisation in mental health in Norway (Mental Health) thru the Questback© platform.

Variables

The questions about experiences of violations and infringements addressed three different kinds of incidents: ones staff/users had heard about, witnessed or experienced themselves. The terms (behaviours) that were specifically used in the questionnaire were if staff/users had experienced rejection, disrespect, lack of privacy, condescending behaviour, neglect, threats, physically rough treatment, verbal harassment, physical violence and ‘shoving, spitting, throwing things’. The questionnaire asked if the staff/users had experienced the mentioned behaviour ‘in the last 14 days’, ‘often’, ‘rarely’ or ‘not’ during the last year. Few staff/users reported having experienced the behaviours during ‘the last 14 days’, and in the analysis, we found this division was not meaningful. The categories were therefore combined, and the question became whether the respondent had experienced the particular behaviour during the last year. The questionnaire contained open answer fields. Quotes from the respondents will be presented together with the findings.

Response rate

Of the 15,576 professionals who received an invitation from their organisations, 1,160 responded, which gives a response rate of 7.5%. Similarly, 320 of the 2,573 users who were invited to participate responded, which gives a response rate of 12.5%.

Ethics

Approval of the study was sought from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (NSD), but the project was considered not to need approval from NSD, because the survey only contained anonymous data. The relevant register numbers are 36361 and 39244. To secure informants’ anonymity personal information was held to a minimum.

Results

Altogether, 1,160 staff and 320 users answered the questionnaire. The staff and users who answered the questionnaire worked in all four regional health authorities and lived in all regions and trusts in Norway. All professional groups in mental health were represented in the sample. The sample consisted of 66% women and 34% men. Of these, 25% were social workers (n = 286), 22% psychologists (n = 258), 20% nurses (n = 233), 18% psychiatrists or psychiatrists in training (n = 211) and 15% assistant nurses or other (n = 172). In the sample of users, 70% were women and 30% men. Further, all users had experience with outpatient mental health care, 57% had experience with acute psychiatric care and 40% had experience with ‘closed wards’. Additional information about the sample is presented in previous articles from the study (Aasland et al., Citation2018; Husum et al., Citation2017). Both staff and users reported experiences with a wide variety of forms of violations and infringements during work or treatment in mental health care. Insufficient support for emotional issues and negligence were the forms of violations and infringements reported most often.

Staff respondents

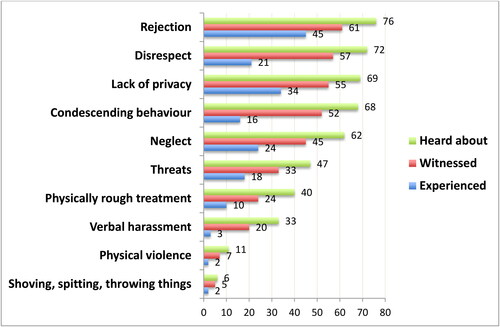

The staff respondents reported numerous experiences of violations and infringements of patients. Over 90% off the staff respondents that had answered the questionnaire had experienced some kind of violations and infringements towards users. Altogether, 21% of the staff said they had treated users with disrespect themselves, and 16% reported having behaved condescendingly towards users. Further, 46% of the staff gave positive answers to the item about having rejected users. Ten percent admitted having been physically rough while providing treatment, and 2% admitted to using physical violence. The staff also reported having witnessed other staff providing violations and infringements. Results are presented in .

Figure 1. Amount of staff experiences with violations and infringements towards users during work in mental health care in percent.

Quotes from the staff in open answer fields are also presented as examples in textbox 1:

Textbox 1:

When working with drug addiction patients, I have experienced this kind of behaviour many times.

As a nurse it is hard to assess my own behaviour, especially when I am under stress. Have answered as honestly as I can.

I am shocked over the bad quality of care on my last workplace! And things never change!

Lack of resources, lack of activity, bad work environment, staff without education and poor economy are the biggest threat[s] and cause bad morale.

I have witnessed nagging, scolding, lack of understanding, lack of patience and resignation.

It is a thin line between threatening and informing users about consequences.

I have witnessed intended provoking acting out, which is then sanctioned.

Have observed terrible staff attitudes toward patients.

Have witnessed intended humiliation toward users by staff.

Have rejected users because of lack of time.

The user attacked, and it was necessary to be physical to prevent damage.

Often physically rough treatment in conjunction with use of mechanical restraints.

Hard to define rejection, neglect and lack of respect. You learn that when you sit and watch a user in seclusion one shall not interact with her or him. The user may feel rejected, neglected and treated with lack of respect, but [are they]?

This is a challenging topic. To view oneself and one’s behaviour is hard. We all make mistakes, and by going through mistakes, we learn.

I have probably done wrong, could have been better, but am learning.

The institution itself humiliates the users who lose self-respect, being afraid to be thrown into hell of madness. They sit in small rooms and hear screams from tortured souls. I have heard it been called the human garbage dump.

Staff have too good protection! I have unfortunately seen too many offences toward patients.

User respondents

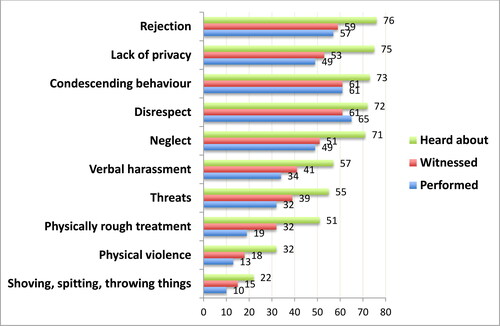

As many as 67% of users had experienced being treated with disrespect, 63% had experienced being treated with condescension and 59% had experienced rejection. Of the more serious kinds of abuse, 18% of users reported physically rough treatment and 13% reported physical violence. All results are presented in .

Figure 2. Amount of user experiences with violations and infringements towards users during treatment in mental health care in percent.

Example on quotes from users are presented in textbox 2:

Textbox 2:

Lack of empathy and lack of respect for [the] user’s family.

Lack of being treated like a human being.

Was put down by [a] male staff [member] who strangled me for about a minute. After that, he kicked me hard in the back.

What is interesting is that it is a few of the staff who are responsible for most of the bad treatment.

I have witnessed condescending behaviour from staff toward very frightened patients.

User groups considered weak are often treated badly. I have witnessed a lot of bad behaviour toward drug addiction patients.

Staff should not be provoked and respond back when users are frustrated and reject [them] because of mental illness.

I have experienced many traumas during mental health care. It has changed me so that I don’t dare to say anything when I am treated badly today.

When I woke up on the acute ward after a suicide attempt, I was scolded like a child for misbehaving.

I was laid on the ground by male caretakers who blocked my respiration for nearly a minute. When he finally released me, he drove his heel hard into my back while I was still lying down. I could not breathe.

Discussion

This study shows that a high number of users had experienced violations and infringements during their time in the mental health system. The informants had heard about and witnessed more violations and infringements of users than they had experienced themselves. A high amount or users had however also experienced violations and infringements themselves. Staff respondents verified these findings by answering that they had also heard about, witnessed and provided violations and infringements. Staff had also heard about and witnessed more violations and infringements than they had provided. A high amount also admitted having performed these kinds of behaviours themselves. Most negative experiences with treatment are relational and involve hurt feelings. Ten percent of staff had provided serious violations and infringements, such as physically rough treatment of users. As we know this is the first study that shows that also mental health care staff have experienced violations and infringements towards users during treatment.

This study implies that violations and infringements is part of daily life in the Norwegian mental health care system. This is in line with previous Norwegian surveys that showed that as many as 30% of users had experienced humiliations during mental health treatment, 10% to the utmost degree (Bjerkan et al., Citation2009, Kjøllesdal et al., Citation2017). The numbers are also in line with findings about residents for older people in nursing homes (Cohen et al., Citation2010, Malmedal et al., Citation2009b). Inadequate emotional care and negligence were most often reported, which are in accordance with studies from nursing homes (Malmedal et al., Citation2009b). In general, users reported higher frequencies of these behaviours than staff. This difference between staff and users experience is also found in other studies (Norvoll & Husum, Citation2011, Henderson, Citation2002). From an ethics of care perspective violations and infringements violate the ethical principles of ‘no harm’ and ‘beneficence’. Many of the actions described also compromise respect for users’ autonomy (Beauchamp & Childress, Citation2009). By collecting data about this topic from both staff and users, and by asking about what they had witnessed and what they had experienced themselves, we confirm that violations and infringements is not just a subjective experience on the users’ side.

This can indicate a culture with embedded epistemic injustice. The taken for granted and everyday instances of reported violations and infringements points to some sense of accepted legitimacy for certain practices (Crichton et al., Citation2017). The institutional setting is a risk factor for violations and infringements and abuse of users (Bowers et al., Citation2004). Institutional factors are power imbalance between users and staff, poor education and high workload among staff (Fagin et al., Citation1996). Kogstad (Citation2009) concludes in the article about protecting mental health clients’ dignity; that clients experiences of infringements cannot be explained without reference to their status as clients in a system which legitimate the right to ignore clients voice as well as their fundamental human rights.

Further, weak leadership is associated with low morale and unprofessionalism (Bowers et al., Citation2009). Leadership on wards may also influence values expressed in care, as well as lack of awareness of ethics in care (Regan et al., Citation2016). Studies from the nursing home sector found that the location and size of the nursing home also was one of the factors predicting violations and infringements of residents (Malmedal et al., Citation2014). Other risk factors for violations and infringements found in research on nursing homes are geographical isolation of the ward, low staffing levels, lack of staff training, lack of nursing leadership and lack of clinical governance (Castle & Engberg, Citation2007).

Another set of risk factors concerns the individual staff member. Another part of this study about staff perception of ethical challenges in relation to working with use of coercive interventions, found that staff thought that some individual staff members tend to escalate aggression, use coercion too quickly or in general treat users in a condescending way. The staff respondents thought also in general that work with coercive practices gave rise to many ethical challenges (Husum et al., Citation2017; Citation2019).

A previous study associated staff’s own ability to regulate their emotions with escalation of conflict and aggression between staff and users in institutional settings. The assumption in this literature review is that when staff have challenges with their own self-regulation, they may lose self-control and behave in ways they normally would consider unethical (Haugvaldstad & Husum, Citation2016). Another factor in relation to the individual staff member is differences in development of empathy. A nursing home study found that staff empathy was negatively correlated with staff burnout syndrome (Aström et al., Citation1991). It is thought-provoking that so many of the staff informants had witnessed fellow staff performing violations and infringements. This suggests that at least some of the behaviour may not be perceived as violations and infringements, and therefore not disguised. Other staff related factors found to lead to violations and infringements are age of the staff, education level and job satisfaction (Malmedal et al., Citation2014). Malmedals et al. finding also suggests that staff do not often ‘blow the whistle’ on fellow staff for performing violations and infringements.

Some user groups are probably especially vulnerable and at risk of violations and infringements. In services for people with drug addiction, for example, negative staff attitudes may be a challenge (Chu & Galang, Citation2013). A ‘vulnerable adult’ may be a person who has a mental disorder, including dementia; has a personality disorder; has a physical or sensory disability; is elderly or frail; has a learning disability; has a severe physical illness; is a substance misuser; is living on social welfare’ or is homeless (Griffith & Tengnah, Citation2009) Many of these characteristics are relevant for users in mental health care (Nieuwenhuis et al., Citation2021). A contributing reason for feeling humiliated or offended maybe one’s mental illness, which may give relational, emotional or cognitive challenges. However, the present study shows that the staff respondents also recognise that violations and infringements towards users occurs. This confirms users’ experiences. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study which confirms users’ experiences of violations and infringements in mental health care.

Another characteristic of the users which may predispose them to being victims of violations and infringements is aggression. Studies on violations and infringements in nursing homes have shown that staff’s negative attitudes towards residents and a high level of conflict and aggression may predispose them to provide violations and infringements (McLafferty & Morrison, Citation2004). In line with this is a tendency, highlighted in research on abuse in nursing homes, to attribute the reasons for violations and infringements to the user’s behaviour or subjective perceptions (Malmedal et al., Citation2014).

An important question concerning users’ safety, ethics and quality of care is how to safeguard users against violations and infringements. The first and most important step is to recognise that users in mental health care are a vulnerable group and prioritise work with ethics in care (Galpin & Parker, Citation2007, Griffith & Tengnah, Citation2009). Voskes et al. claim that ethical quality of care and quality of care are intertwined (Voskes et al., Citation2021a). Use of ethical reflection groups may therefore contribute to heightening the quality of care in general (Hem et al., Citation2018b). Further, multidimensional interventions have been shown to predict violations and infringements in nursing homes (Malmedal et al., Citation2014) and these findings may also be valid for institutional care in mental health. Safeguards for vulnerable adults should ideally be multidimensional (Whitelock, Citation2009). Concrete suggestions aimed to improve ethical quality of care in nursing homes are: to implement person-centred care and a family-friendly environment and thereby decrease isolation, resident aggression, and inadequate care; breed a culture where staff feel nurtured, appreciated and valued, give time for reflection upon own and others’ practice, implement training and education programmes that aim to increase the staffs’ skill to, identify, document, and report inadequate care, abuse and neglect, implement training and education programmes that aim specifically to increase the staffs’ skills in reducing residents’ aggression and behaviour problems. Further develop national laws, guidelines and procedures for detecting and handling inadequate care, abuse and neglect in nursing homes and raise public awareness on the problem (Malmedal, Citation2013). Many of these suggestions are probably relevant in mental health care as well.

Other treatment initiatives that may improve ethical quality of care is ‘rights-based’ approaches (Whitelock, Citation2009) and approaches based on care ethics as ‘High and Intensive Care (Voskes et al., Citation2021a).

Since lack of appropriate education of staff is found to predispose violations and infringements, leaders and health authorities should ensure that staff have appropriate education and ethical training while working with vulnerable patients. Institutions need to develop and implement mechanisms for understanding and evaluating acts of violations and infringements, and staff should be encouraged to speak out on behalf of users (Malmedal et al., Citation2009a, Citation2009b). In a systematic review of studies of patients’ experiences from 16 countries, it was found that the four following dimensions were important to the experience of in-patients mental health services: high-quality relationship; averting negative experiences of coercion; a healthy, safe and enabling physical and social environment; and authentic experiences of patient-centred care. Important elements for users were values like trust, respect, safe wards, information and explanation about clinical decision, therapeutic activities, and family inclusion in care (Staniszewska et al., Citation2019).

Limitation and strengths of the study

The low response rate is a limitation of this study. However, the sample is of a considerable size. Low response rates are also found in other online studies, and response rates for online questionnaire in general are lower than for mailed questionnaires (Crouch et al., Citation2011). Studies also show that in spite of considerable nonresponse rates, results may be of scientific value (Hellevik, Citation2016). Further, there may be self-selection bias on the part of both staff and users, in that the staff and users who answered the questionnaire had the most negative experiences. The research topic may be challenging and difficult to talk about, and the anonymity of the online questionnaire is therefore considered to be a strength of the study. Both staff and users may have felt safe and free to express difficult and under-recognised experiences that may otherwise be shameful to reveal.

Conclusion

A high number of staff and users report having experienced users being exposed to violations and infringements during mental health treatment. This study found that mental health care staff also report and acknowledge that some users experience violations and infringements during mental health care. As a consequence, this is to the best of our knowledge, the first study that confirms users’ experiences of inadequate mental health care also from a staff perspective. It is therefore of considerable value and important for this group of vulnerable users that this issue be further examined.

Relevance for clinical practice

The topic of users’ experiences of violations and infringements is undervalued and should be taken seriously. Effort should be made to map occurrence of violations and infringements, as to prevent this practice. This could be done with regular screening of users’ experiences, and routine work with ethics and user-safety in care. This could improve quality of care and users’ satisfaction, as well as mental health care staff’s ethical awareness of and empathy towards users’ needs and feelings.

Funding

The project has received funding from Ekstrastiftelsen (NGO founding) Nr: 2014/FOM5645.

References

- Aasland, O. G., Husum, T. L., Førde, R., & Pedersen, R. (2018). Between authoritarian and dialogical approaches: Attitudes and opinions on coercion among professionals in mental health and addiction care in Norway. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 57, 106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.02.005

- Aström, S., Nilsson, M., Norberg, A., Sandman, P. O., & Winblad, B. (1991). Staff burnout in dementia care–relations to empathy and attitudes. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 28(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7489(91)90051-4

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2009). Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford University Press.

- Bjerkan, A. M., Pedersen, P. B., & Lillleng, S. (2009). Brukerundersøkelse blant døgnpasienter i psykisk helsevern for voksne 2003 og 2007 (Investigation of users view on mental health care for adults 2003 and 2007). SINTEF Research.

- Bodin, B. G., & Velasco, D. (2007). Krenkelser er vanlig innom psykiatrien (Humiliatons are common in psychiatry). Sveriges Radio. https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=83&artikel=1448337

- Bowers, L., Alexander, J., Simpson, A., Ryan, C., & Carr-Walker, P. (2004). Cultures of psychiatry and the professional socialization process: The case of containment methods for disturbed patients. Nurse Education Today, 24(6), 435–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2004.04.008

- Bowers, L., Allan, T., Simpson, A., Jones, J., & Whittington, R. (2009). Morale is high in acute inpatient psychiatry. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 44(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0396-z

- Castle, N. G., & Engberg, J. (2007). The influence of staffing characteristics on quality of care in nursing homes. Health Services Research, 42(5), 1822–1847. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00704.x

- Chu, C., & Galang, A. (2013). Hospital nurses’ attitudes toward patients with a history of illicit drug use. The Canadian Nurse, 109(6), 29–33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23862324/23862324

- Cohen, M. I. R. I., Halevy-Levin, S., Gagin, R. O. N. I., Priltuzky, D. A. N. A., & Friedman, G. (2010). Elder abuse in long-term care residences and the risk indicators. Ageing and Society, 30(6), 1027–1040. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X10000188

- Crichton, P., Carel, H., & Kidd, I. (2017). Epistemic injustice in psychiatry. BJPsych Bulletin, 41(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.115.050682

- Crouch, S., Robinson, P., & Pitts, M. (2011). A comparison of general practitioner response rates to electronic and postal surveys in the setting of the National STI Prevention Program. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 35(2), 187–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00687.x

- Fagin, L., Carson, J., Leary, J., De Villiers, N., Bartlett, H., O’Malley, P., West, M., Mc Elfatrick, S., & Brown, D. (1996). Stress, coping and burnout in mental health nurses: Findings from three research studies. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 42(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409604200204

- Frueh, B. C., Knapp, R. G., Cusack, K. J., Grubaugh, A. L., Sauvageot, J. A., Cousins, V. C., Yim, E., Robins, C. S., Monnier, J., & Hiers, T. G. (2005). Patients’ reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 56(9), 1123–1133. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.9.1123

- Fulmer, T. T., & O’Malley, T. A. (1987). Inadequate care of the older people: A health care perspective on abuse and neglect. Springer Pub. Co. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327655jchn0601_10

- Galpin, D., & Parker, J. (2007). Adult protection in mental health and inpatient settings: An analysis of the recognition of adult abuse and use of adult protection procedures in working with vulnerable adults. The Journal of Adult Protection, 9(2), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668203200700009

- Griffith, R., & Tengnah, C. (2009). The protection of vulnerable adults. British Journal of Community Nursing, 14(6), 262–266. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2009.14.6.42596

- Haugvaldstad, M. J., & Husum, T. L. (2016). Influence of staff’s emotional reactions on the escalation of patient aggression in mental health care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 49(Pt A), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.09.001

- Hellevik, O. (2016). Extreme nonresponse and response bias. Quality & Quantity, 50(5), 1969–1991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0246-5

- Hem, M. H., Gjerberg, E., Husum, T. L., & Pedersen, R. (2018a). Ethical challenges when using coercion in mental healthcare: A systematic literature review. Nursing Ethics, 25(1), 92–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016629770

- Hem, M. H., Molewijk, B., Gjerberg, E., Lillemoen, L., & Pedersen, R. (2018b). The significance of ethics reflection groups in mental health care: A focus group study among health care professionals. BMC Medical Ethics, 19(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0297-y

- Henderson, J. (2002). Experiences of ‘care’ in mental health. The Journal of Adult Protection, 4(3), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668203200200020

- Husum, T. L., Hem, M. H., & Pedersen, R. (2017). A survey of mental healthcare staff’s perception of ethical challenges related to the use of coercion in care. Beneficial coercion in psychiatry? Mentis.

- Husum, T. L., Legernes, E., & Pedersen, R. (2019). "A plea for recognition" Users’ experience of humiliation during mental health care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 62, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2018.11.004

- Husum, T. L., Thorvarsdottir, V., Aasland, O., & Pedersen, R. (2020). ‘It comes with the territory’ – Staff experience with violation and humiliation in mental health care – A mixed method study. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71, 101610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101610

- Kjøllesdal, J., Iversen, H., Danielsen, K., Haugum, M., & Holmboe, O. (2017). Pasienters erfaringer med døgnopphold innen psykisk helsevern i 2016. [Inpatients’ experiences with specialist mental health care in 2016]. Rapport nr.2017: 317 Folkehelseinstituttet (Institute for National Public Health).

- Kogstad, R. (2009). Protecting mental health clients’ dignity - The importance of legal control. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 32(6), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.09.008

- Malmedal, W., Hammervold, R., & Saveman, B.-I. (2009a). To report or not report? Attitudes held by Norwegian nursing home staff on reporting inadequate care carried out by colleagues. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 37(7), 744–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809340485

- Malmedal, W., Hammervold, R., & Saveman, B.-I. (2014). The dark side of Norwegian nursing homes: Factors influencing inadequate care. The Journal of Adult Protection, 16(3), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAP-02-2013-0004

- Malmedal, W., Ingebrigtsen, O., & Saveman, B. I. (2009b). Inadequate care in Norwegian nursing homes–As reported by nursing staff. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 23(2), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00611.x

- Malmedal, W. (2013). Inadequate care, abuse and neglect in Norwegian nursing homes. [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology]. NTNU Open. https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/267983

- McLafferty, I., & Morrison, F. (2004). Attitudes towards hospitalized older adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(4), 446–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03122.x

- Nieuwenhuis, J. G., Lepping, P., Mulder, N. L., Nijman, H. L. I., Veereschild, M., & Noorthoorn, E. O. (2021). Increased prevalence of intellectual disabilities in higher-intensity mental healthcare settings. BJPsych Open, 7(3), e83. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.28

- Norvoll, R., & Husum, T. L. (2011). Som natt og dag? – Om forskjeller i forståelse mellom misfornøyde brukere og ansatte om bruk av tvang. (As night and day - Difference in perception about use of coercion between users and staff in mental health care). Arbeidsforskningsinstituttet.

- Nyttingnes, O., Ruud, T., & Rugkåsa, J. (2016). ‘It’s unbelievably humiliating’-Patients’ expressions of negative effects of coercion in mental health care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 49(Pt A), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.08.009

- Olofsson, B., & Norberg, A. (2001). Experiences of coercion in psychiatric care as narrated by patients, nurses and physicians. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01641.x

- Regan, S., Laschinger, H. K., & Wong, C. A. (2016). The influence of empowerment, authentic leadership, and professional practice environments on nurses’ perceived interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(1), E54–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12288

- Staniszewska, S., Mockford, C., Chadburn, G., Fenton, S.-J., Bhui, K., Larkin, M., Newton, E., Crepaz-Keay, D., Griffiths, F., & Weich, S. (2019). Experiences of in-patient mental health services: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 214(6), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.22

- Stanley, N., Manthorpe, J., & Penhale, B. (1999). Institutional abuse: Perspectives across the life course. Psychology Press.

- Svindseth, M. F., Dahl, A. A., & Hatling, T. (2007). Patients’ experience of humiliation in the admission process to acute psychiatric wards. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480601129382

- UKOM (2020). Statens undersøkelseskommisjon for helse- og omsorgstjenesten (The State Commsions for Inquiry into the Health and Care Services). Dødsfall på en akuttpsykiatrisk sengepost (Death on an acute psychiatric ward). Norway.

- Voskes, Y., van Melle, A. L., Widdershoven, G. A. M., van Mierlo, A. F. M. M., Bovenberg, F. J. M., & Mulder, C. L. (2021a). High and intensive care in psychiatry: A new model for acute inpatient care. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 72(4), 475–477. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800440

- Whitelock, A. (2009). Safeguarding in mental health: Towards a rights‐based approach. The Journal of Adult Protection, 11(4), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800440

- Williams, J., & Keating, F. (2000). Abuse in mental health services: Some theoretical considerations. The Journal of Adult Protection, 2(3), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/14668203200000021