Abstract

Aim

The purpose was to describe nurses’ experiences of suicide prevention work in primary health care (PHC).

Background

Suicide is the tenth most common cause of death among adults. PHC has an important role in suicide prevention work, as patients often had contact with PHC before their suicide rather than with specialist psychiatric care. Nurses often have the first contact with the patient and are responsible for triage and assessment, making them important in suicide prevention work. Previous studies shed light on suicide prevention in a primary care context, but the nurses’ voices are missing.

Methods

Fifteen qualitative interviews were conducted with nurses in primary health care. Data was analyzed according to conventional content analysis techniques.

Findings

Nurses may avoid asking questions about suicidality for fear of what to do with the answer. To support the nurses’ ability in suicide prevention work, both educational and practical experience are fundamental. There was a lack of clarity about who is carrying responsibility for the patient, and it turned out to be difficult to help the patient move further to the next care institution. There was a need for guidelines as well as routines for collaboration with other care actors in suicide prevention work.

Conclusion

The PHC organization does not support nurses in suicide prevention, therefore they need the right conditions for their work. Suicide prevention needs to be given greater focus and space within education as well as training in the ongoing clinical work, which can be performed with less extensive efforts.

Introduction

Suicide is defined as an intentional, self-inflicted act that results in death (National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2020). Globally, approximately 700,000 people die by suicide yearly (WHO, Citation2021a). In Sweden, the number of insured suicides is estimated to be around 1,100 annually (Swedish Public Health Agency, Citation2021). Suicide is the tenth most common cause of death among adults and the second most common among young adults aged 15–29 (Cross et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2014). In total, more men than women die of suicide, although it varies in different parts of the world (WHO, Citation2014). In industrialized countries, suicide is three times more common in men than women, while in developing countries, it is one and a half times more common. A clear link between mental illness and suicide has been identified in developing countries (WHO, Citation2021b). Of those who died of suicide, 80 percent had a primary health care (PHC) contact in the past year and 40 percent in the month before the suicide, while a third had contact with a specialist psychiatric clinic (Cross et al., Citation2019; Hauge et al., Citation2018; National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2016). The WHO (Citation2021a) is striving to reduce the number of suicides by a third by year 2030. Suicide prevention needs to be performed in the entire health care system, and especially in PHC, where the greatest diversity of people with mental illness (WHO, Citation2021a) and those who later died by suicide, sought care (Cross et al., Citation2019; Wittink et al., Citation2020). PHC refers to health and medical care activities where outpatient care is provided without delimitation in terms of diseases, age or patient groups (SFS 2017:30, 2017:30, Citation2017). PHC is responsible for the basic medical assessment, treatment, nursing, preventive work and rehabilitation that does not require special medical or technical resources or any other special skills. PHC emanates a holistic view of health and well-being with a focus on the patient’s individual needs (Mughal et al., Citation2021). In Sweden PHC is the first way into health care (Anell et al., Citation2012; Burström et al., Citation2017) and contributes in an important way to improve the health of the entire population. PHC is team-based where doctors, nurses and other professions are represented (Anell et al., Citation2012). In Sweden the majority of PHC (?) visits in recent years have been to nurses and not physicians (National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2021), even though the physician has been seen as the dominant occupational group in healthcare (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). As nurses are the first contact of the patients in PHC, they have an important role and responsibility for triaging the need for care and to refer the patient to appropriate care contacts (Anell et al., Citation2012; Björkman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the nurse meets patients who have physical as well as mental disorders, which makes their profession complex (Janlöv et al., Citation2018). During the 1990s, significant changes, including that most care should be offered within PHC, were implemented in the health care system (Anell et al., Citation2012). This shift meant that more patients with mental illness should primarily turn to PHC for care and not to specialist psychiatry (Sobczak, Citation2009). Although this has increased the burden on PHC, it also opens up opportunities to work on suicide prevention through early identification (Mughal et al., Citation2021). Today, more patients with mental illness are treated in primary care, and nurses meet them on a daily basis (Agyapong et al., Citation2011; Björkman et al., Citation2018; Flaskerud, Citation2012; Mughal et al., Citation2021). Mental illness, when treated together with physical illnesses, tends to receive less attention and many patients somatize mental symptoms and seek treatment for physical ailments (Karlsson et al., Citation2021; McAndrew et al., Citation2019). Depression and concomitant somatic disease also increase the risk that depressive symptoms are misinterpreted as symptoms of the somatic disease and therefore are not noticed (National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2016). When patients seek help for physical symptoms, and mental symptoms are prominent during the visit, it leads to challenges for the nurses (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Karlsson et al., Citation2021). Obstacles to the assessment and treatment of mental disorders in PHC may be due to a lack of interaction with specialist psychiatric clinics and lack of knowledge about psychiatric illnesses among health care staff (Agyapong et al., Citation2011; McAndrew et al., Citation2019). Studies have shown that there is a lack of knowledge and a need for additional competence in PHC to meet the increased number of patients with mental illness (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Flaskerud, Citation2012). The human-to-human model emphasizes the importance of the nurse using herself therapeutically by being aware of her own understanding and interpreting both her own and others’ behavior and paying attention to the dynamics of human behavior (Smith, Citation2020; Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015). In addition to this, the nurse needs to be able to integrate this and evidence-based knowledge in order to achieve high-quality care that can promote the patient’s trust and confidence in the interaction with the nurse. Communication is a central and necessary part of good nursing (Shelton, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2020), and a professional relationship can only be created when both the patient and the nurse see each other as a unique person (Shelton, Citation2016; Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015).

Although knowledge about suicide prevention has increased over the past 10 years, only 38 countries had ratified national suicide prevention programs in 2018 (WHO, Citation2021a). Previous studies have mainly focused on educating physicians in PHC about suicide prevention (Saini et al., Citation2014; Secker et al., Citation1999), which has been shown to have positive effects in suicide prevention (Mughal et al., Citation2021). However, still many physicians state that they do not have the time and lack confidence to manage patients at risk of suicide (Dixon et al., Citation2021). An intervention carried out in collaboration between Portugal, Ireland, Hungary and Germany among nurses, social workers and teachers, showed that education increased confidence and knowledge and the ability to detect and respond to suicidal behavior at an early stage (Coppens et al., Citation2014). In Iran, a suicide prevention program helped to detect depressed patients to a greater extent and at the same time reduced the number of suicides (Malakouti et al., Citation2015). In specialist psychiatry, suicide risk assessment and management of suicidal patients is a key component in care, while in PHC it is an unexplored area (Mughal et al., Citation2021; Saini et al., Citation2014). Nurses play an important role as they talk to the patients to a greater extent more informally about their living conditions and stressors that may be outside the patient’s immediate medical concerns (Wittink et al., Citation2020). The nurses are an important part of suicide prevention as they are the ones who primarily meet the patients in PHC (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Bolster et al., Citation2015). Although previous studies of suicide preventive interventions in PHC show promising results, these need to be adapted to the health care staff and patients within the countries where they are performed. Thus, to gain insights into how suicide prevention works in PHC in Sweden, the aim of this study was to describe nurses’ experiences of suicide prevention work in primary health care.

Methods

Study design and sample

A descriptive qualitative method was chosen because it gives participants a chance to shed light on their experiences of a phenomenon, in this study, nurses’ experiences of suicide prevention in primary healthcare (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). Content analysis focuses on the context or contextual meaning of the text and is a useful method when the aim is to describe a phenomenon in an area where existing research is limited (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005).

Participants and setting

In order to collect in-depth information from the right respondents, a convenience sample was used (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). The heads of the various PHC centers gave permission to carry out the study and passed on the names of presumptive nurses who met the inclusion criteria to the research team. The participants were contacted by telephone. The inclusion criteria were: registered nurse and working in PHC for at least 1 year. A total of 15 nurses working in PHC participated in the study, aged between 30 and 66 years. Eight of the nurses were registered nurses and seven were district nurses. Their working experiences in PHC care ranged from 2 to 41 years. All had experiences of suicide intervention in a PHC setting. The nurses were included from two different regions in Sweden and worked at nine different PHC centers within these regions. Written informed consent was obtained from all nurses who participated in the study after they received written information about the study (Patton, Citation2015). The researchers guaranteed that the participants’ confidentiality would be preserved when the results were presented, and participation in the study was voluntary.

The nurses chose where the interviews would be conducted in order to create a calm and relaxed interview situation (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). Ten of the interviews took place physically at the various health care centers in secluded rooms, with minimal risk of being interrupted. Five of the interviews were conducted via Zoom, partly due to the Covid-19 pandemic and in some case for scheduling reasons, when the interview took place outside working hours.

Interviews

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with the support of an interview guide that was designed based on the purpose of the study. The interview guide was developed jointly by the researchers who were involved in the study. Semi-structured interviews are used when researchers have questions about a specific topic but want the informants to talk freely in their own words (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). All nurses received the same questions based on the interview guide. The questions were: Can you describe your experiences of suicide prevention in PHC? Can you describe in which situations suicide risk assessments are made and by whom? Can you describe how you act when you meet a patient who express suicidal thoughts? Follow-up questions—can you describe a situation? can you develop it further? how did you experience the situation?—were asked to deepen their answers or to clarify their statements. The interviews took place individually with each informant and lasted between 18 to 49 minutes, with a median time of 32 minutes. The nurses were interviewed by RW, IK and ML, all of who have knowledge about suicide prevention. The interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were conducted during the autumn of 2021, between October and December.

Data analysis

The data was analyzed according to conventional content analysis. Conventional content analysis is a recognized research method for analyzing text data and is used in a study design whose purpose is to describe a phenomenon in areas where present research is limited (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). After transcription, all the data was read repeatedly by each author, to gain a sense and understanding of the whole. To capture important concepts and thoughts related to the purpose of the study, an ongoing discussion between the authors was held. Important parts that corresponded to the purpose were highlighted and extracted from the text, and then resulted in codes. The codes were labeled, sorted and organized into ten different clusters, which were then sorted into two categories with a total of six subcategories based on their similarities and differences. The process was non-linear and the authors had an ongoing dialogue about how the content was coded and categorized in the best way. This was done in order to find as close descriptions of the text as possible, although some interpretation may be needed (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Quotes have been identified and presented to increase the credibility of the different categories and subcategories in the results (Patton, Citation2015).

Ethical considerations

The ethical standards of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (2013) were followed. The study was conducted in line with the principles from General Data Protection Regulation (Troeth & Kucharczyj, Citation2018). The research process and how the method and results were structured followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines “COREQ” (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Results

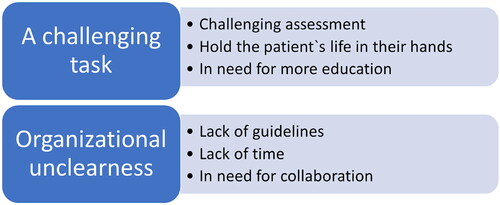

The analysis revealed two categories that shed light on the nurses’ experiences of suicide prevention in PHC: A challenging task and Organizational unclearness (). The categories with their subcategories are presented below.

A challenging task

In this category, challenges emerge that the nurses face in suicide prevention. In order to feel confident in how to work with suicide prevention, the importance of experience emerged. It was especially challenging to make assessments by telephone and to meet people with mental illness. Furthermore, the importance of receiving support from colleagues, and feeling safe in knowing where to refer the patient further and that someone else takes over the responsibility, emerged.

Challenging assessments

Nurses with less working experience expressed more uncertainty about suicide prevention and making suicide risk assessments than those with several years of experience. Suicide prevention was perceived as more challenging in telephone contact with patients. It became a more difficult assessment as they could not read body language and facial expressions, and they only had the patients’ verbal communication and voices to act on. The nurses also described a helplessness when the patients were on the phone, and they did not know whether the patient would seek further help or try to die of suicide.

If they are not in place, you cannot take them by the hand and make sure that they come to the next instance; if it is the case that they need emergency help, you only have the phone as a tool… it is a huge challenge. (p. 7)

However, some of the nurses described that they found it easier to work with suicide prevention and ask questions about suicide over the phone than at a physical meeting, since they felt protected behind the phone. When the patient was in the room, some found it more challenging because they did not have access to rating scales and support questions in the same way as by the phone, which led to them feeling insecure about asking questions about suicide.

Meeting patients with mental illness appeared to be more complex, as many of them presented with somatic symptoms even though the nurses understood that it was about mental illness. This made the nurses afraid of losing the patient’s confidence if they talked too much about their somatic symptoms, while in fact it was about the patient not feeling well mentally. In these meetings, a challenge emerged in not putting in too many personal values based on previous experiences of people with mental illness. They found it difficult to trust these patients and there was some suspicion about whether the patient was telling the truth about having suicidal thoughts or intentions. On the other hand, there was also a fear among the nurses of not being able to respond to psychiatric problems in the right way without aggravating or triggering psychiatric symptoms or suicidal intentions in the patients.

If patients feel that they are not listening to, they may do something when the conversation is over. You do not know that… it is your biggest fear. (p. 5)

Hold the patient’s life in their hands

The nurses felt that their role in suicide prevention was to pass the patient on to someone else for help. If the conversation revealed that the patient was unwell, the nurses had a hard time letting go of the conversation and asking them to wait until someone else called them. They felt that the patient’s life lay in their hands until someone else took over. The nurses felt more confident and safe in situations where the patient had been handed over to someone with more knowledge. If there was no one else who could take over the case, or when the patients were referred on without in-depth assessment, a frustration was created among the nurses. They brought this with them home after working hours. It therefore appeared important to find out who they could refer the patient on to and to follow the patient until he or she had ended up right.

Help! Do I have responsibility for another person’s life here now? It becomes quite obvious. (p. 14)

When the nurses suspected a patient’s risk of suicide, they saw it as their responsibility to get a physician’s appointment for further assessment. This was challenging, as they were almost never available. The nurses could also face resistance from other professions if they had assessed that a patient needed to see a physician. Discussions could then arise as to whether it was PHC that was responsible for the patient. Suicide prevention work was perceived as heavy. The visits could be strenuous and the nurses felt that their own mood was negatively affected by the tough conversations. Although the nurses considered it human to be affected, they raised the need to ventilate after the patient had been referred.

It may be about one’s own anxiety, I do not know, but I have a very hard time. You want to hold them in your hand until the next person takes over. (p. 10)

In need of more education

Suicide prevention was described as challenging and there was a need for training in how to deal with patients with mental illness. The nurses lacked training at the same time as they are the ones who meet the patients and ask questions about suicide. It also emerged that the nurses lacked lectures from their employer on how to work in a good way to prevent suicide, and they requested both internal and external education to feel more secure in the assessments they are facing. They felt that they did not have sufficient knowledge to help patients who express suicidal thoughts. Furthermore, it emerged that there is a lack of education about mental illness and suicide prevention in both the basic education for becoming a nurse and the district nurse education. The nurses who felt that they had no education in the subject described, to a lesser extent, that the responsibility for suicide prevention lay on them as they did not have the right knowledge.

Suicide risk assessments are a very difficult chapter and we probably need education that applies to the nurses in telephone counselling; strengthen that you have the faith to ask, manage, and then that you know what to do. (p. 13)

The nurses who had received training on risk factors for suicide and had access to guidance on how to treat suicidal patients, and what measures could be taken, had a higher understanding of, and emphasized the importance of, working with suicide prevention. With increased knowledge, it became more natural for nurses to ask questions about suicide. After the training, they felt less anxious about asking the wrong questions, which contributed to them more often daring to ask patients about thoughts of wanting to take their lives.

The training has been good, so now I think that we nurses feel safer in asking. (p. 6)

Organizational unclearness

In this category, it appears that the nurses experience that there is uncertainty and ambiguity in suicide prevention in PHC, which became most prominent among those who did not have experience. Guidelines are lacking and visits are limited in time, which creates poor conditions for suicide prevention. There was also an ambiguity regarding collaboration with external care actors.

Lack of guidelines

The nurses expressed that there are no guidelines on how to work with suicide prevention in PHC. Suicide prevention was often linked to suicide risk assessments. It was only when the nurses suspected that the patient was suffering from mental illness that they asked questions about their mental state and whether they had any plans to die of suicide. The nurses felt that it was their responsibility to determine whether a patient was suicidal, and in the less experienced nurses this created a great deal of uncertainty. The uncertainty concerned both what they would do to reach the patient in the conversations and what questions to ask in order to catch suicidal thoughts. The uncertainty was also about how they would handle the situation in a purely practical way if suicidal thoughts was detected. As there were no guidelines for suicide prevention, the nurses focused a lot on their gut feeling, both in the assessment and the measures it led to.

I know that we have clear guidelines in other areas… but not in this area, at least not what I have seen and heard. (p. 8)

Although there were no guidelines, some of the nurses used a suicide assessment instrument. The assessments were then perceived to be more standardized and not so subjective, which made it easier, especially for new nurses. Although it was easier, the nurses saw risks in following rating scales too strictly, as the subjective part and the gut feeling were not allowed to take place in the assessment. Assessments of patients’ possible suicidality were described as a fingertip feeling where the subjective assessments also needed to be accommodated. However, it became clear that rating scales reduced the uncertainty in the assessment of those with less experience.

Yes… guidelines… we have a suicide assessment instrument to use. (p. 10)

It emerged that there was also a lack of clarity about how suicide prevention work should be documented. This meant that the nurses were very careful to document both the patients’ mental illness and that they had asked questions about suicide, so that they would have their “backs free” if something were to happen to the patient.

Lack of time

The nurses experienced the lack of time for suicide prevention work as a stressful moment. In the work in PHC, conversations with patients were limited to a few minutes. At the same time, the nurses described that it takes time to get the patient to tell if they have thoughts about suicide. If the nurses do not take the time to listen properly to the patient, they felt that it was easy to make a wrong assessment. It was also stressful that the limited time would include documentation. The tight schedule could affect the assessments and lead to the nurses not going deeper into the conversations for fear of what would come up, as there was no time to deal with suicidal thoughts.

There is a risk that you do not ask because you feel that you do not have time to take care of the answer. It becomes an ethical stress. (p. 15)

Despite this, the nurses tried to prioritize patients with mental illness and give them longer visiting hours when possible. A key factor in the suicide prevention work was to give patients with mental illness time, which the nurses raised wishes for.

To just give them one minute extra, just letting them finish telling. If you are too stressed in the beginning, you will have to work much longer later to get the patient with you… neither you nor the patient wins time on that. (p. 7)

Some nurses described that several years of experience have made them more confident in the assessments and in dealing with the time pressure that exists as nurses in PHC with short conversations and meetings. The nurses with more experience showed that time was set aside for these conversations, even though it stressed them out and they knew that they would fall behind in the planning for the next working day. They therefore experienced that they exposed both themselves and their colleagues to stress, as statistics are kept of how many calls the nurses manage during their work shift.

In need of collaboration

Several of the nurses experienced good collegial support in PHC; however, they missed support from other health care providers around suicidal patients. It was difficult to refer them on and the nurses expressed frustration at not being able to help the patients enough. At the same time, they felt that they had a responsibility to refer the patient on to the right health care provider. The experience of the nurses made it easier to collaborate with other health care providers. If the nurses had worked for several years, personal contacts could be of advantage to easily get in touch with other health care providers. The nurses felt a need for collaboration to avoid the patients being handed back and forth between different actors. Some of the nurses felt that the patients had no choice but to turn to PHC, as specialist psychiatry was so difficult to access.

This is where they come because they come nowhere else… you cannot call psychiatry in general… they will only refer to primary health care, everyone refers to primary health care. (p. 13)

A strength in PHC was considered by the nurses to be that they are more accessible to patients and not as distanced as specialist psychiatry. In PHC, the nurses felt that they had a good personal knowledge of the patients, which could facilitate the assessments. It was experienced positively that the patients turned to PHC primarily in the event of mental illness.

I think we should be the first stage of healthcare. It should be a little reassuring that you should be able to turn to your primary health care center if you do not feel well, no matter what it is. (p. 15)

Discussion

In the results of the study, the nurses’ experience emerged as the most important characteristic in the suicide prevention work. In the absence of guidelines and routines, the nurses’ experiences became even more important, as the nurses often acted on intuition. There was a lack of clarity within the organization about who was responsible for the patient, and the nurses described it as difficult to help the patient further to the next care institution. The suicide prevention work was also described as a challenging task with difficult assessments, lack of education in the area, lack of time and a great deal of personal responsibility.

The study showed that many of the nurses found it challenging to work on suicide prevention when they were new to the profession and highlighted experience as a fundamental prerequisite. Experience increased the nurses’ self-confidence and courage to take on patients who showed suicidality. To be able to provide optimal suicide prevention, a competent and confident healthcare staff is required (Hogan & Grumet, Citation2016; Mughal et al., Citation2021). Challenges in suicide prevention work are something that emerge not only in PHC but also in emergency care (Shin et al., Citation2021) as well as in other professions, such as with physicians (Solin et al., Citation2021). Nursing students also experience that they do not gain enough knowledge and techniques during their education to feel safe in suicide prevention work (Ferguson et al., Citation2020). This is problematic because the results of this study show that nurses must take a great deal of responsibility in suicide prevention work, regardless of level of experience. Here, an effort needs to be made, as the WHO emphasizes the importance of increasing the competence of healthcare professionals when it comes to suicide prevention (WHO, Citation2014). Through training in suicide prevention, healthcare professionals can be strengthened in their work, at the same time as training has shown positive changes in their attitudes and confidence to be able to work within suicide prevention (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Bolster et al., Citation2015; Dueweke & Bridges, Citation2018; Giacchero Vedana et al., Citation2017). Among the nurses in this study, it emerged that those who received education about mental illness and suicidality felt that suicide prevention work became more important and prioritized. Even less extensive training in suicide prevention consisting of a shorter lecture and discussions of health-care staffs experiences and watching a video by an expert of lived experience of suicidality, has been shown to give good results (Solin et al., Citation2021). Nurses who were allowed to participate in a 3-hour suicide prevention training showed an increased confidence in daring to raise their concerns and ask questions in the care of suicidal patients (Solin et al., Citation2021). The training for staff should be adapted to the profession and all healthcare professionals who meet patients should have knowledge of signs of suicidality, and the follow-up measures, if such need to be taken (Bolster et al., Citation2015; Hogan & Grumet, Citation2016). This together indicates that suicide prevention work needs to be given greater focus and space within the education as well as in the ongoing clinical work, and that less extensive efforts can make a big difference.

Our results showed that nurses felt more secure in asking questions about suicide as their experiences increased. It is also a well-established truth in all Swedish care, both somatic and psychiatric care, that questions about possible suicidality cannot evoke anything within the patient. Therefore, one should rather ask once too much than not at all. However, always asking about detailed descriptions, or suggesting methods of suicide could be problematized. These type of questions can create mental images and contribute to a causation when the event is imagined for a person’s inner self repeatedly (Ng et al., Citation2016). This is called “flash forward” and has received relatively little attention in previous research. Mental imagery of suicide has been a neglected but potentially critical feature of suicidal ideation (Hales et al., Citation2011).

In the care of patients with mental illness, the nurses experienced challenges in not including their own values based on previous experiences. Negative attitudes to mental illness are already evident in nursing students (Hastings et al., Citation2017; Ihalainen-Tamlander et al., Citation2016). If students carry these negative attitudes into clinical work, there is a risk that they will have a reduced interest in working with patients with mental illness after completing their education (Hastings et al., Citation2017). Some studies have shown that healthcare professionals tend to treat people with mental illness less thoroughly and effectively (Thornicroft, Citation2011). Despite medical needs, it happens that they are not referred to further care (Sebastian & Beer, Citation2007). Less experienced nurses tend to have an increased social discrimination against and fear of patients with mental illness (Ihalainen-Tamlander et al., Citation2016). To create a nurse/patient relationship, the nurse needs to use a disciplined and intellectual approach to mental health problems (Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015). Lack of sympathy in the nursing interaction can be negative for patients and affect whether they accept or reject their illness. If the nurse sees the patient as a unique individual and not as a stereotype, the conditions for a relationship are created, which helps the patient to take responsibility for their own care (Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015).

The nurses in this study said that the patients often sought care for somatic symptoms, when the real reason was about them not feeling mentally well. Because patients with mental illness feel stigmatized, it may be easier for them to report somatic symptoms. This can make nurses experience the patients as more unpredictable and demanding (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Karlsson et al., Citation2021). Our study also showed that the nurses expressed difficulties in trusting whether patients with mental illness were telling the truth. It is important to be aware that patients who feel stigmatized may have more difficulties in daring to express suicidal thoughts (Leavey et al., Citation2017). Education has been seen to reduce these stigmatizing values and prejudices, which is a prerequisite for creating interest among students and nurses in wanting to work with people with mental illness (Ihalainen-Tamlander et al., Citation2016). Both formal competence in the form of education, and real competence obtained through experience, have been shown to increase the confidence of district nurses to meet people with mental illness (Janlöv et al., Citation2018). The positive changes that education leads to can benefit patients who seek PHC help for mental illness so that they can feel stigmatized to a lesser extent, and experience less obstacles if the nurses who meet the patients have the right skills (Björkman et al., Citation2018). Due to the changes that have taken place in healthcare, with more focus on PHC, more nurses will meet patients with mental illness who have an increased risk of suicide (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Mughal et al., Citation2021). According to the human-to-human relationship model, it is not enough to care for the patient; to achieve good care, an integration of broad knowledge is required in parallel with a therapeutic approach (Shelton, Citation2016; Smith, Citation2020; Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015). Through this, the nurse can alleviate suffering and give hope (Shelton, Citation2016).

The study revealed that the nurses felt that lack of time was an obstacle in suicide prevention work. It was only when the nurses gave time for conversations that it became clear whether the patient was suicidal or not. Lack of time makes it difficult for the patient to build trust and can be an obstacle to communicating about the mental illness and the possible risk of suicide (Leavey et al., Citation2017; Poghosyan et al., Citation2019). In the relationship between the patient and the nurse, it is the nurse who is responsible for the relationship being developed and maintained (Shelton, Citation2016; Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015). Healthcare professionals state that suicidal patients can be emotionally isolated, which makes it difficult for them to talk about thoughts about suicide (Björkman et al., Citation2018; Vandewalle et al., Citation2019a). A caring relationship needs to be established for the patient to have the conditions to express their mental illness (Grundberg et al., Citation2016). By giving the nurse time for the conversation, the relationship can be strengthened and further developed. It also emerged from the results of this study that some nurses stated that they avoided asking in-depth questions when the patient showed symptoms of mental illness because they did not feel they had time to help the patient. This is confirmed in previous studies that have shown that nurses in PHC experience the lack of time so stressfully that they ignored the patient’s mental symptoms because those conversations tend to take longer (Janlöv et al., Citation2018; Maxwell et al., Citation2013; Obando Medina et al., Citation2014). The combination of time pressure and stigma indicates that more time needs to be set aside for conversations about mental illness in PHC to capture suicidal thoughts in patients.

The results of the study show that there is an organizational ambiguity and lack of routines and guidelines on how to handle patients who are assessed to be suicidal. Several of the nurses used rating scales in the assessments of suicide risk to increase their security. The instruments can serve as pedagogical support for less experienced healthcare professionals and can act as a security and create an alliance if they are used correctly. However, the scientific evidence, whether the instruments can contribute to the clinical assessment in the individual case, has been questioned. (Swedish Agency for Medical & Social Evaluation, Citation2015). Although different instruments can have accurate sensitivity and specificity, the instruments are supported by too few studies to allow for evaluations of accuracy (Runeson et al., Citation2017).

The nurses in this study describe difficulties in the collaboration with other health care actors and in helping the patient further to the next care institution. A lack of collaboration between somatic and psychiatric care can have serious consequences for the patient and contribute to increased stress in relatives (Björk Brämberg et al., Citation2018). The nurses in the result experienced a great deal of personal responsibility in suicide prevention work and stated a fear of being responsible if a patient die of suicide. Previous studies show that these shortcomings in collaboration make the whole process more time consuming and lead to stress for the nurse around patients dying of suicide when they are under their’ responsibility (Janlöv et al., Citation2018; Vandewalle et al., Citation2019b). Perhaps a closer collaboration with relatives would contribute to the suicide prevention work? Previous research has shown that the family often possesses important knowledge about the suicidal patient, but that they feel barred from having a role in the care (Hultsjö et al., Citation2022). Healthy family relationships and open communication are crucial in being able to prevent suicide. Involving relatives and recognizing the role of relatives in care can be challenging, but healthcare professionals can be the one who links relatives and the patient together, which is crucial for ensuring a safe environment around a suicidal patient (Edwards et al., Citation2021). Thus, relatives’ knowledge and experiences of the patient can be valuable and therefore need to be taken into account in a PHC context.

It became clear that nurses in this study lack routines and guidelines for the management of suicidal patients, and whether the guidelines exist or not, they are not sufficiently known by the study informants. In attempts to help the patient on to the next care institution, the nurses encounter obstacles and may end up in ethical dilemmas about who bears the actual responsibility for the patients. In an international perspective, primary care, in low- and middle-income countries, is identified as a suitable care institution for offering care in the event of mental illness (Esponda et al., Citation2020). However, previous studies have described how PHC caregivers do not feel they have the resources to deal with the increased pressure of patients experiencing mental illness and identified deficiencies within the organization (Janlöv et al., Citation2018; Leavey et al., Citation2017; Poghosyan et al., Citation2019). The leadership of an organization that works with patients with mental illness should work for a culture that is characterized by a commitment to safety and ensure that there is support for the staff who perform the suicide prevention work and meet the suicidal patients (Hogan & Grumet, Citation2016). Despite the stated goal of lowering the suicide rate and prioritizing suicide prevention, our results show that there is still a great deal of uncertainty in the area among nurses in PHC. In order to achieve nursing created through human-to-human nursing theory, it is not only necessary to overcome stereotypes and focus on patient care, it is also necessary to pay attention to the needs of nurses (Staskova & Tothova, Citation2015).

Methodological considerations

The study included nurses working in PHC, regardless of working experience and further education, which was a conscious choice to capture experiences of suicide prevention among nurses with less and more experience. The sample includes a large variation in terms of working experiences, age and education, and they worked in several different PHC centers within two different regions. Thus, their experiences can be considered to holds key elements that mirror a larger population of nurses in PHC (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). All the informants were women. This can be seen as a limitation to not capture men’s perspective on suicide prevention in PHC, as some study has shown that women tend to be more positive in their attitudes toward patients with mental illness compared to men (Ihalainen-Tamlander et al., Citation2016). This may be due to the fact that 90% of all registered nurses in Sweden are female (National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2021). According to Polit and Beck (Citation2021), it is recommended that the interviews are conducted in a neutral environment where the interview does not risk being interrupted. Ten of the interviews were performed in secluded rooms at the nurses’ workplaces and, due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, five were performed digitally via Zoom. The fact that some of the interviews were conducted via Zoom gave the interviewer the opportunity to assess the nurses’ facial expressions and body language and opened up interviews for small talk and follow-up questions, in the same way as face to face interviews (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). Interviewing can be intense and challenging and requires concentration and energy on the part of the interviewer (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). To ensure the quality of the interviews, the interviewers discussed among themselves throughout the data collection how the interviews went on. During the last interviews, nothing new emerged in the data, which may indicate that the data was saturated (Polit & Beck, Citation2021). The study was conducted in a PHC context in Sweden, which may limit its transferability. To enable the reader to establish the degree of similarity between our studied case and the case to which the findings might be transferred sufficiently, a clear description of the context and demographic backgrounds of the participants are given (Patton, Citation2015).

Conclusion

The primary care organization does not support the nurses in suicide prevention work, which highlights the need for guidelines as well as routines for collaboration with other care actors. PHC, as it is designed today, poses a risk of missing suicidal patients, as nurses may refrain from asking about suicidal thoughts due to fear of getting affirmative answers and not having the knowledge and time to take care of this. Suicide prevention work requires both formal competence in the form of education and real competence obtained through experience. Therefore, suicide prevention work needs to be given greater focus both in education as well as in the ongoing clinical work. Nurses need the right skills to meet suicidal patients, as it has been shown to reduce stigma in patients and make nurses pay more attention to and prioritize suicide prevention work to a greater extent. As patients may have difficulties communicating suicidal thoughts, nurses need to be given time and competence for this work. Relatives today do not have an obvious role in PHC. As they possess important information and know how the patient is in their habitual state, they could play a significant role in suicide prevention work.

Disclosure

The authors have confirmed that all authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship credit (www.icmje.org) as follows: (1) substantial contributions to the conception and design of or acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agyapong, V. I., Conway, C., & Guerandel, A. (2011). Shared care between specialized psychiatric services and primary care: The experiences and expectations of consultant psychiatrists in Ireland. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 42(3), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.42.3.e

- Anell, A., Glenngård, A. H., & Merkur, S. (2012). Sweden health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 14(5), 1–159. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/164096/e96455.pdf

- Björk Brämberg, E., Torgerson, J., Norman Kjellström, A., Welin, P., & Rusner, M. (2018). Access to primary and specialized somatic health care for persons with severe mental illness: A qualitative study of perceived barriers and facilitators in Swedish health care. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0687-0

- Björkman, A., Andersson, K., Bergström, J., & Salzmann-Erikson, M. (2018). Increased mental illness and the challenges this brings for district nurses in primary care settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(12), 1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1522399

- Bolster, C., Holliday, C., Oneal, G., & Shaw, M. (2015). Suicide assessment and nurses: What does the evidence show? Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20(1), 2.

- Burström, B., Burström, K., Nilsson, G., Tomson, G., Whitehead, M., & Winblad, U. (2017). Equity aspects of the primary health care choice reform in Sweden – A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0524-z

- Coppens, E., Van Audenhove, C., Iddi, S., Arensman, E., Gottlebe, K., Koburger, N., Coffey, C., Gusmão, R., Quintão, S., Costa, S., Székely, A., & Hegerl, U. (2014). Effectiveness of community facilitator training in improving knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in relation to depression and suicidal behavior: Results of the OSPI-Europe intervention in four European countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.052

- Cross, W. F., West, J. C., Pisani, A. R., Crean, H. F., Nielsen, J. L., Kay, A. H., & Caine, E. D. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of suicide prevention training for primary care providers: A study protocol. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1482-5

- Dixon, M. A., Hyer, S. M., & Snowden, D. L. (2021). Suicide in primary care: How to screen and intervene. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 56(5), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/00912174211042435

- Dueweke, A. R., & Bridges, A. J. (2018). Suicide interventions in primary care: A selective review of the evidence. Families, Systems & Health, 36(3), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000349

- Edwards, T. M., Patterson, J. E., & Griffith, J. L. (2021). Suicide prevention: The role of families and carers. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 13(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12453

- Esponda, G. M., Hartman, S., Qureshi, O., Sadler, E., Cohen, A., & Kakuma, R. (2020). Barriers and facilitators of mental health programmes in primary care in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(1), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30125-7

- Ferguson, M., Reis, J., Rabbetts, L., McCracken, T., Loughhead, M., Rhodes, K., Wepa, D., & Procter, N. (2020). The impact of suicide prevention education programmes for nursing students: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(5), 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12753

- Flaskerud, J. H. (2012). DSM-5: Implications for mental health nursing education. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(9), 568–576. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.704132

- Giacchero Vedana, K. G., Magrini, D. F., Zanetti, A., Miasso, A. I., Borges, T. L., & Dos Santos, M. A. (2017). Attitudes towards suicidal behaviour and associated factors among nursing professionals: A quantitative study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(9-10), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12413

- Grundberg, Å., Hansson, A., Hillerås, P., & Religa, D. (2016). District nurses’ perspectives on detecting mental health problems and promoting mental health among community-dwelling seniors with multimorbidity. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(17–18), 2590–2599. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13302

- Hales, S. A., Deeprose, C., Goodwin, G. M., & Holmes, E. A. (2011). Cognitions in bipolar affective disorder and unipolar depression: Imagining suicide. Bipolar Disorders, 13(7–8), 651–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00954.x

- Hastings, T., Kroposki, M., & Williams, G. (2017). Can completing a mental health nursing course change students’ attitudes? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(5), 449–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1278810

- Hauge, L. J., Stene-Larsen, K., Grimholt, T. K., Øien-Ødegaard, C., & Reneflot, A. (2018). Use of primary health care services prior to suicide in the Norwegian population 2006–2015. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 619. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3419-9

- Hogan, M. F., & Grumet, J. G. (2016). Suicide prevention: An emerging priority for health care. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(6), 1084–1090. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1672

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hultsjö, S., Ovox, S. M., Olofsson, C., Bazzi, M., & Wärdig, R. (2022). Forced to move on: An interview study with survivors who have lost a relative to suicide. Perspective in Psychiatric Care. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.13049

- Ihalainen-Tamlander, N., Vähäniemi, A., Löyttyniemi, E., Suominen, T., & Välimäki, M. (2016). Stigmatizing attitudes in nurses towards people with mental illness: A cross-sectional study in primary settings in Finland. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(6–7), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12319

- Janlöv, A. C., Johansson, L., & Clausson, E. K. (2018). Mental ill-health among adult patients at healthcare centres in Sweden: District nurses experiences. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 32(2), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12540

- Karlsson, J., Hammar, L. M., & Kerstis, B. (2021). Capturing the unsaid: Nurses’ experiences of identifying mental ill-health in older men in primary care-a qualitative study of narratives. Nursing Reports (Pavia, Italy), 11(1), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11010015

- Leavey, G., Mallon, S., Rondon-Sulbaran, J., Galway, K., Rosato, M., & Hughes, L. (2017). The failure of suicide prevention in primary care: Family and GP perspectives - A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 369. 10.1186/s12888-017-1508-7

- Malakouti, S. K., Nojomi, M., Poshtmashadi, M., Hakim Shooshtari, M., Mansouri Moghadam, F., Rahimi-Movaghar, A., Afghah, S., Bolhari, J., & Bazargan-Hejazi, S. (2015). Integrating a suicide prevention program into the primary health care network: A field trial study in Iran. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/193729

- Maxwell, M., Harris, F., Hibberd, C., Donaghy, E., Pratt, R., Williams, C., Morrison, J., Gibb, J., Watson, P., & Burton, C. (2013). A qualitative study of primary care professionals’ views of case finding for depression in patients with diabetes or coronary heart disease in the UK. BMC Family Practice, 14, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-46

- McAndrew, L. M., Friedlander, M. L., Litke, D., Phillips, L. A., Kimber, J., & Helmer, D. A. (2019). Medically unexplained physical symptoms: What they are and why counseling psychologists should care about them. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(5), 741–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019888874

- Mughal, F., Gorton, H. C., Michail, M., Robinson, J., & Saini, P. (2021). Suicide prevention in primary care. Crisis, 42(4), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000817

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2016). The mission of primary care A survey of how the county councils’ assignments to primary care are formulated. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2016-3-2.pdf

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2020). Suicide. https://patientsakerhet.socialstyrelsen.se/risker-ochvardskador/vardskador/suicid/

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2021). Follow-up of primary care and the transition to closer care. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2020-6-6826.pdf

- Ng, R., Di Simplicio, M., McManus, F., Kennerley, H., & Holmes, E. A. (2016). ‘Flash-forwards’ and suicidal ideation: A prospective investigation of mental imagery, entrapment and defeat in a cohort from the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey. Psychiatry Research, 246, 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.018

- Obando Medina, C., Kullgren, G., & Dahlblom, K. (2014). A qualitative study on primary health care professionals’ perceptions of mental health, suicidal problems and help-seeking among young people in Nicaragua. BMC Family Practice, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-129

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage.

- Poghosyan, L., Norful, A. A., Ghaffari, A., George, M., Chhabra, S., & Olfson, M. (2019). Mental health delivery in primary care: The perspectives of primary care providers. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(5), 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.08.001

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2021). Nursing Research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (11th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Runeson, B., Odeberg, J., Pettersson, A., Edbom, T., Jildevik Adamsson, I., & Waern, M. (2017). Instruments for the assessment of suicide risk: A systematic review evaluating the certainty of the evidence. PLoS One, 12(7), e0180292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180292

- Saini, P., While, D., Chantler, K., Windfuhr, K., & Kapur, N. (2014). Assessment and management of suicide risk in primary care. Crisis, 35(6), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000277

- Sebastian, C., & Beer, M. D. (2007). Physical health problems in schizophrenia and other serious mental illnesses. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 3(02), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646407001148

- Secker, J., Pidd, F., & Parham, A. (1999). Mental health training needs of primary health care nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 8(6), 643–652. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00308.x

- SFS 2017:30. (2017). Health care law. Ministry of Social Affairs. Hälso- och sjukvårdslag (2017:30) Svensk författningssamling 2017:2017:30 t.o.m. SFS 2021:648 – Riksdagen.

- Shelton, G. (2016). Appraising Travelbee’s human-to-human relationship model. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, 7(6), 657–661.

- Shin, H. D., Cassidy, C., Weeks, L. E., Campbell, L. A., Drake, E. K., Wong, H., Donnelly, L., Dorey, R., Kang, H., & Curran, J. A. (2021). Interventions to change clinicians’ behavior related to suicide prevention care in the emergency department: A scoping review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(3), 788–846. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-21-00149

- Smith, M. (2020). Nursing theories and nursing practice chapter 6 (5th ed.). FA Davis.

- Sobczak, J. A. (2009). Managing high-acuity-depressed adults in primary care. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 21(7), 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00422.x

- Solin, P., Tamminen, N., & Partonen, T. (2021). Suicide prevention training: Self-perceived competence among primary healthcare professionals. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 39(3), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2021.1958462

- Staskova, V., & Tothova, V. (2015). Conception of the human-to-human relationship in nursing. Science Direct, 17(4), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kontakt.2015.09.002

- Swedish Agency for Medical and Social Evaluation. (2015). Instrument for assessment of suicide risk. https://www.sbu.se/sv/publikationer/SBU-utvarderar/instrument-for-bedomning-av-suicidrisk/

- Swedish Public Health Agency. (2021). Suicide. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/folkhalsorapportering-statistik/tolkad-rapportering/folkhalsans-utveckling/resultat/halsa/suicid-sjalvmord/

- Thornicroft, G. (2011). Physical health disparities and mental illness: The scandal of premature mortality. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 441–442. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092718

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Troeth, S., Kucharczyj, E. (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and user research. https://medium.com/design-research-matters/general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr-and-user-research-e00a5b29338e

- Vandewalle, J., Beeckman, D., Van Hecke, A., Debyser, B., Deproost, E., & Verhaeghe, S. (2019a). Contact and communication with patients experiencing suicidal ideation: A qualitative study of nurses’ perspectives. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(11), 2867–2877. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14113

- Vandewalle, J., Beeckman, D., Van Hecke, A., Debyser, B., Deproost, E., & Verhaeghe, S. (2019b). ‘Promoting and preserving safety and a life-oriented perspective’: A qualitative study of nurses’ interactions with patients experiencing suicidal ideation. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(5), 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12623

- WHO. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- WHO. (2021a). Suicide. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

- WHO. (2021b). LIVE LIFE: An implementation guide for suicide prevention in countries. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341726/9789240026629-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Wittink, M. N., Levandowski, B. A., Funderburk, J. S., Chelenza, M., Wood, J. R., & Pigeon, W. R. (2020). Team-based suicide prevention: Lessons learned from early adopters of collaborative care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1697213