Abstract

This integrative literature review describes nurses’s and patients’ perceptions of care in psychiatric intensive care units (PICU). The database search was conducted in April 2020. PRISMA checklist and Mixed Method Appraisal Tool guided the identification and evaluation of the studies (n = 21). Data was analyzed with qualitative content analysis. Nurses perceived PICU as a challenging work environment where their primary task was to ensure the unit’s safety. Patients views on their treatment varied from positive to negative. Patients wished to have more privacy and supportive interaction. Findings can be used as a basis in developing care practices and staff’s further education in PICUs.

Introduction

Psychiatric patients may perform challenging behavior such as aggression and violence (e.g., Chukwujekwu & Stanley, Citation2011; Grassi et al., Citation2001); thus, nurses in psychiatric units are frequently exposed to aggression and violence (Moylan & Cullinan, Citation2011). Patients with an increased risk of violence are often treated in psychiatric intensive care units (PICU, Napicu Citation2014), thereby making patient aggression and violence particularly common in PICUs (Wynaden et al., Citation2001).

PICUs are psychiatric wards with a small number of beds and higher level of staff compared to general wards and a design that is easy to observe and term PICU is mostly used in UK since 1970s (Cullen et al., Citation2018). There are different types of PICUs and several other terms used to refer to PICU in literature e.g. extra care wards, high dependency, special care, locked wards and low secure units. Patients in PICUs are typically male, relatively young, diagnosed with schizophrenia or mania (Bowers et al., Citation2008) and often have various problems, such as substance abuse (Pereira et al., Citation2005). Moreover, in the High and Intensive Care (HIC) model, all patients are admitted to the general High Care section (HC) and severely agitated patients are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) attached to HC and treated one-on-one with a nurse. In addition, term HIC is mostly used in Netherlands (Van Melle et al., Citation2019). In addition, the term close-observation area is used to describe units similar to PICU in Australia. They are usually small, locked units that are placed within an acute psychiatric facility and designed for close observation, safety, and frequent nursing interventions (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). The term PICU is used more in UK and Europe than in the USA, and forensic units are not included in the term PICU.

Patients are referred to PICU units’ various way’s e.g. pre-set admission criteria as a guiding to assess patients suitability for the unit or using acute psychiatric wards normal admissions routine to coercive practices (Crowhurst & Bowers, Citation2002; Cullen et al., Citation2018; Van Melle et al., Citation2019). Patients transfer to PICU and seclusion are often implemented on a compulsory basis (Cullen et al., Citation2018). During PICU care reporting and documentation is highlighted in the HIC model (Van Melle et al., Citation2019).

Even though segregating patients to PICUs has managed to decrease threatening and violent incidents (Vaaler et al., Citation2006, Citation2011) and the use of coercive measures (Georgieva et al., Citation2010), it remains a challenging and complex work environment for the staff (Dawson et al., Citation2005; Zarea et al., Citation2013). Managing and communicating with patients in the PICU requires expertise and confidence from nurses (Wynaden et al., Citation2001) as they must balance between safety concerns and control while simultaneously providing psychological and emotional support for patients (Zarea et al., Citation2013). In addition, administration of sedative medication and restraints (Winkler et al., Citation2011) as well de-escalation techniques (Price et al., Citation2018) are often used.

Similarly to nurses, PICU treatment can be stressful for patients as well (Lamothe et al., Citation2019). Rules and limitations might be experienced as frustrating, and patients may feel threatened by other patients, though some patients have also experienced their stay in a PICU safe and beneficial (NHS, Citation2010). Moreover, patients have reported lack of adequate surroundings and activities (NHS, Citation2010) to trigger aggressive behavior (Meehan et al., Citation2006).

Patients and nurses may experience psychiatric care and interaction differently (Shattell et al., Citation2008), and sometimes they have conflicting interests and views regarding the care (Tyson et al., Citation2002). The perceptions of nurses and patients, however, have merely been studied in general and acute psychiatric wards, thus psychiatric intensive care has received less attention. It is pivotal to clarify both nurses’ and patients’ perceptions regarding PICU care due to its distinct nature and complexity.

Aims

This integrative literature review describes patients’ and nurses’ perceptions of care in psychiatric intensive care units. The research questions are: What is known about nurses’ perceptions on working in psychiatric intensive care unit? What is known about patients’ perceptions about care in psychiatric intensive care?

Materials and methods

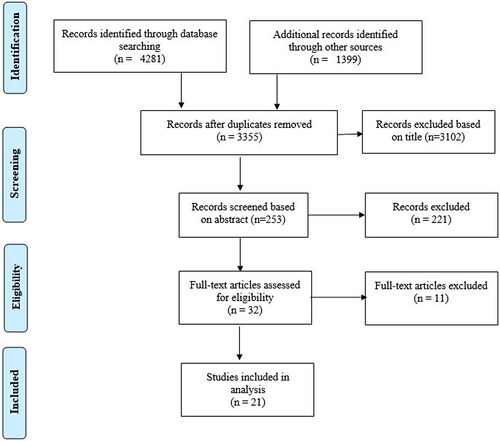

An integrative literature review was applied because it allows the inclusion of diverse methodologies to gain comprehensive understanding. The five-stage approach by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) was used. The PRISMA checklist (Moher et al., Citation2009, Appendix A) and the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 (Hong et al., Citation2018) guided the reporting of the study.

Stage 1: Problem identification

For this review, a psychiatric intensive care unit was defined as a specialized unit treating violent psychiatric patients who could not be treated safely in a less secure environment. Forensic psychiatric units were excluded as they differ from PICUs and usually treat patients for a longer time.

Stage 2: Literature search

A systematic search using five electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrane, PsycINFO and Web of Science) was conducted in April 2020. The search terms were chosen based on the PI(C)O framework (Stone, Citation2002) with the population being psychiatric patients and nurses, the interest being treatment in psychiatric intensive care and the outcome being the experiences. Search phrases were formed in collaboration with an information specialist and contained also suitable MeSH terms that followed the guidelines for each database (). A manual search was conducted from the reference lists of the included articles and by scanning through the first 50 pages of Google Scholar with the term ‘psychiatric intensive care unit’.

Table 1. Search phrases used.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1. Examined adult patients’ or nurses’ perceptions of the psychiatric intensive care (including studies, in which only partial data was about nurses’ or patients’ perceptions of the psychiatric intensive care. In cases where data was provided also from other sources, results had to be reported in a way which enabled separating nurses’ and patients’ perceptions.); 2. Peer-reviewed empirical articles published in English in scientific journals. Studies conducted in child or adolescent psychiatric intensive care or forensic units were excluded as well as theoretical articles, case reports, conference abstracts, book chapters, trial registers, internet resources and unpublished records.

In total, 4,281 articles were identified through the database search. Articles were screened by title and afterwards by abstract. Full text articles were finally read among those that were selected based on the abstract. 16 studies were included in the analysis based on a systematic database search and five studies by manual search. Full-text articles (n = 11) were excluded with reasons (). In total, 21 articles were included in the literature review (). All the selected articles are presented in .

Table 2. Full-text articles excluded (n = 11) with reasons.

Table 3. Articles (n = 21) included in literature review.

Stage 3: Data evaluation

The Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018, was used for quality assessment of the included studies (Hong et al., Citation2018) and scored between 0–7. Three authors carried out the evaluation independently and differences in evaluations were solved by discussion. Overall, the quality of studies was generally good. Detailed appraisals are presented in Appendix A.

Stages 4 and 5: Data analysis and presentation

The data analysis was two-phased. It began with data reduction (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005), where data was extracted from the included studies, including author, year, country, study aim, methodology, sample, main findings, reliability and suggestions for further research. At the latter phase, a content analysis was applied to analyze the data as it is designed to classify text into categories by finding repeated patterns from the data (Grove et al., Citation2012). In the content analysis, all the articles were read again carefully. In the results sections, nurses’ and patients’ perceptions from psychiatric intensive care were marked. These were then compiled into two different tables, one related to nurses’ perceptions and one to patients’ perceptions. Then, these were condensed and coded according to similarities and differences. Afterwards, the codes were classified into categories and finally main themes were identified from the data. An example of the analysis is presented in and all the categories are presented in .

Table 4. Example of the analysis on nurses’ experience.

Table 5. Main themes and categories based on content analysis.

Results

General description of the studies

The included studies (n = 21) were published between 1993–2018 in the UK (n = 9), Sweden (n = 5), Australia (n = 3), Norway (n = 2), the USA (n = 1) and the Netherlands (n = 1). The study settings included psychiatric intensive care units (n = 16), psychiatric seclusion areas (n = 2), closed observation areas (n = 1), psychiatric observation and intensive in-patient care (n = 1) and a secure unit of a specialist psychiatric hospital (n = 1).

Eight studies were quantitative and included a descriptive cross-sectional design (n = 6) and descriptive explorative design (n = 2). Eight studies were qualitative, using a descriptive qualitative design (n = 6), grounded theory design (n = 1) and qualitative critical incident technique (n = 1). Five studies used a mixed-methods design, including descriptive cross-sectional design combining quantitative and qualitative data (n = 4) and pre-posttest combined with qualitative interviews (n = 1). Data from the included quantitative studies was mostly collected using questionnaires (n = 9) with addition to one quantitative observation. Qualitative data was collected with interviews (n = 7), observation (n = 2) and focus group (n = 1).

Participants

The participants were patients in eight studies, staff in nine studies and both in four studies. The participating staff included registered nurses, assistant nurses, doctors, and psychologists (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017; O’Brien et al., Citation2014) and with both genders in different studies. The reported age range was 23–65 years (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008; Stevenson, Citation2013). Participants had work experience from <1 to 33 years (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Evans & Petter, Citation2012; McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008; Stevenson, Citation2013). Five studies did not report any specific characteristics of the participating nurses (Gentle, Citation1996; Loubser et al., Citation2009; Mackay et al., Citation2005; Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018; Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015).

The participating patients’ mean age was 34–38 (Ash et al., Citation2015; Hyde et al., Citation1998; Iversen et al., Citation2011; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993), ranging from 18–82 (Ash et al., Citation2015; Hyde et al., Citation1998; Iversen et al., Citation2011; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017; Schröder & Björk, Citation2013; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). Gender deviation of patients varied among selected studies (Ash et al., Citation2015; Bos et al., Citation2012; Hyde et al., Citation1998; Iversen et al., Citation2011; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017; Schröder & Björk, Citation2013; Vaaler et al., Citation2005; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). Patients’ diagnoses included schizophrenia, psychosis, drug psychosis bipolar disorder, severe depression, substance misuse, organic psycho-syndrome, personality disorders (Ash et al., Citation2015; Bos et al., Citation2012; Hyde et al., Citation1998; Iversen et al., Citation2011; McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017; Schröder & Björk, Citation2013; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). The length of stay in psychiatric intensive care varied from under 1 day to 13 months (Ash et al., Citation2015; Bos et al., Citation2012; Hyde et al., Citation1998; Iversen et al., Citation2011).

Main findings

Nurses’ perceptions of working in a psychiatric intensive care unit

Three main themes were identified from nurses’ perceptions within psychiatric intensive care: (1) Balancing between different care practices, (2) PICU as a challenging work environment and (3) Nursing interventions in PICU.

Balancing between different care practices

Safety rules and control

Safety was a high priority in PICUs (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Gentle, Citation1996), as nurses had to protect patients from displaying aggressive behavior toward others or themselves (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). This was done by maintaining order and structure, setting limits and rules (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008), observing patients (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004) and providing protective care (Gentle, Citation1996; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). Nurses informed patients about the rules (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010). Sometimes safety was maintained by restricting patients physically (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018). Ensuring safety justified the use of coercive actions and was believed to be in the patients’ best interest (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010). However, despite violent incidents, nurses reported feeling quite safe in the PICUs (Evans & Petter, Citation2012; O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

Therapeutic and empowering engagement

Trustworthy and therapeutic relationships with patients were essential in reducing the risk of violence and aggression in PICU (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). To create a therapeutic relationship, nurses used their personality, showed compassion and sensitivity and had a humble attitude (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). Moreover, nurses made themselves available to patients to create a sense of safety, trust, and closeness (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010), and empowered patients by involving them in decision-making (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015). Sometimes caring was linked to secure patients’ basic human needs, like giving food (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). Understanding patients’ situation, lowering the barriers between nurses and patients (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010) and personal interaction (McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017) enabled supportive encounters (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008) which benefited the patient.

PICU as a challenging work environment

Physical features

The physical features of PICU were experienced challenging. The PICU physical layout is usually open and planned to ensure safety and easy observation (Gentle, Citation1996; O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008), resulting in a lack of privacy for the patients (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). To resolve this, nurses suggested separate patients’ rooms in the PICU to protect patients’ integrity and to be used as a sanctuary (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008). Nurses stated also that limited space in the PICU may compromise the care (Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015), for example nurses not being able to directly access the medication room (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). Moreover, nurses reported insufficient bathrooms and toilets, no doors on some bedrooms, and no curtains on windows decreasing the positive atmosphere in PICUs. Insufficient recreational spaces and activities often resulted in patient boredom (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004).

Emotional oppression

Working in a PICU can be unpredictable (Björkdahl et al., Citation2010) as well as mentally and physically exhausting (Evans & Petter, Citation2012) due to the diverse mix of patients (Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015) often disputing with staff (Salzmann-Erikson et al., Citation2008) and high patient turnover (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018). Nurses sometimes had to witness injustices toward patients (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). In addition, PICU nurses did not have enough treatment options for seclusion and restraints (Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015) and the use of physical restrictions caused ethical concerns (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018).

Interpersonal co-operation

PICU nurses valued support from their colleagues. Talking and debriefing were recognized to help nurses’ possible fears regarding violence (Evans & Petter, Citation2012). However, co-operation with colleagues could be problematic: sometimes other teams did not offer help with dangerous situations (Evans & Petter, Citation2012), or nurses felt that colleagues had unrealistic expectations of their expertise in patient management (Salzmann-Erikson, Citation2018). In addition, nurses reported lack of management support and uninformed changes in policy (Evans & Petter, Citation2012).

Nursing interventions in PICU

Interaction with patients and patient assessment

Interaction between nurses and patients included listening, nurse and patient actively doing something together, implementing different interventions to help patients relax in PICU, de-escalating and negotiating with patient and psychoeducation (Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015). While interacting with patients, nurses simultaneously assessed both physical and mental wellbeing of the patient, including distress and vital signs (Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015). In addition, nurses evaluated possible signs of aggression to prevent violent incidents (Mackay et al., Citation2005; Ward & Gwinner, Citation2015).

Patients’ perceptions of care in a psychiatric intensive care unit

Two main themes were identified from patients’ perceptions of care within psychiatric intensive care unit: (1) Issues connected with high satisfaction with nursing. (2) Issues connected with low satisfaction with nursing.

Issues connected with high satisfaction with nursing

Collaboration with staff

Interacting with nurses was highly appreciated by patients (Bos et al., Citation2012; McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). Patients who received supportive talk during their stay, rated significantly higher quality of care (Schröder & Björk, Citation2013). Patients stated the PICU staff being mainly approachable and helpful (Ash et al., Citation2015; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993) and they felt that they received support, a sense of respectful treatment (Iversen et al., Citation2011) and empathy from staff (Schröder & Björk, Citation2013). In addition, patients liked doing things with nurses, such as playing cards and doing puzzles (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). Moreover, patients made comments about staff helping them relax and making them feel homely (Hyde et al., Citation1998).

Issues connected with a low satisfaction with nursing care

Inappropriate facilities and environment

The PICU environment was described as contributing to care in a negative way (Ash et al., Citation2015) and patients were not satisfied with the environment (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017). Patients stated that the physical environment could be improved and suggested improvements such as exercise facilities, better toilets, a spa and particularly more personal space (Ash et al., Citation2015). Patients reported not having enough activities during the PICU treatment (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993) which contributed to lower satisfaction as well (Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). Patients’ satisfaction with recreational facilities was significantly associated with less violent incidents (Hyde et al., Citation1998).

Feelings of abandonment

Interaction with staff was not always sufficient according to patients, as it was sometimes restricted (Bos et al., Citation2012; O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017), leading to negative feelings (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017), like not being treated at all (Bos et al., Citation2012; O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). Patients felt that their negative feelings were not addressed (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004) or complaints taken seriously (Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993) by staff. Patients also reported that staff was not available when needed (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017) and patients were left on their own, causing fear (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017). Moreover, patients wanted to be included in their own treatment (Ash et al., Citation2015; McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993) but participation was quite low (Lemmey et al., Citation2013; Schröder & Björk, Citation2013) which evoked feelings of unhappiness amongst patients (Ash et al., Citation2015).

Lack of information about care

While being admitted to a PICU, patients wished to gain adequate information from nurses (McAllister & McCrae, Citation2017). However, patients did not always receive enough information regarding their treatment (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017; Schröder & Björk, Citation2013). Unmet information needs included for example the side effects of medication (Iversen et al., Citation2011), possible aggression of other patients (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017), discharge planning (Hyde et al., Citation1998), legal status and rights or decisions made about their care afterward rounds (Lemmey et al., Citation2013).

Sense of insecurity

Safety was a high priority in PICUs (Bos et al., Citation2012). However, patients reported being physically assaulted (Loubser et al., Citation2009) and being involved in aggressive incidents (Bos et al., Citation2012) while being admitted. Despite this, PICU patients reported feeling generally safe (Bos et al., Citation2012; Iversen et al., Citation2011). According to patients, restrictions, interaction with other patients, smoking, illness, staff provocation and lack of privacy were causes of violence in PICUs (Loubser et al., Citation2009). In addition, dissatisfaction with overall care possibly contributed to violent incidents (Hyde et al., Citation1998).

Criticism of safety precautions

Due to safety policies, patients were closely monitored (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017), and rules in the PICU were often strict (Bos et al., Citation2012, Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017) which created a lack of privacy and personal space (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004; Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017) contributing to lower satisfaction in the PICU (Schröder & Björk, Citation2013; Wykes & Carroll, Citation1993). Due to these restrictions, patients felt all their rights were withdrawn (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017) and they criticized the strict rules (Bos et al., Citation2012) and the frequent presence of security staff (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004). In addition, a restricted environment was described to be as counterproductive (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017), leading patients to feel insecure, confined (Salzmann-Erikson & Söderqvist, Citation2017) and like being in prison (O’Brien & Cole, Citation2004).

Discussion

The studies included in this review examined health care staff’s and patients’ perceptions related to psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs). To our knowledge, there is little research conducted on nurses’ and patients’ perceptions of care in PICUs. Based on this review, both nurses and patients perceive PICUs as challenging environment due to various issues.

Nurses described PICUs as a challenging working environment because they must acknowledge different types of care practices. On the other hand, nurses must ensure safety in the unit by following and maintaining strict restrictions and safety regulations, and on the other hand, they have to offer supportive and therapeutic discussions to the patients. This two-fold working approach may overstress nurses and poses an ethical dilemma as well: how to care for patients safely without using too much restrictive methods, to respect their self-determination and to offer enough opportunities for supportive interaction. Similar ethical challenges are reported in studies by Kontio et al. (Citation2012) and Haugom et al. (Citation2019). To reduce occupational stress and decrease challenging ethical situations in the PICU environment, there must be a clear nursing framework and opportunities for nurses to discuss it. This benefits patients and supports their recovery.

Patients were not satisfied with their treatment in PICUs. They deemed the restrictions negative and as diminishing self-determination, and this increased dissatisfaction during the PICU care. In addition, patients wished more interaction with nurses. These findings concur with earlier studies (Kontio et al., Citation2012; Keski-Valkama et al., Citation2010). Due to safety issues, PICU consists mainly of open spaces which help nurses to observe and maintain safety. Conversely, patients perceived this as problematic: the lack of personal private spaces often created tension in PICUs, and patients wished more privacy. Similar findings can be found in other studies (Meehan et al., Citation2006; NHS, Citation2010), where patients highlighted the importance of adequate surroundings in the PICU environment.

Therapeutic relationship and communication, being essential nursing interventions in PICUs, were according to patients’ most significant issues during PICU care. Respectful treatment, receiving support and empathy from staff were perceived as contributing to high patient satisfaction with care and high quality of care. Indeed, creating supportive relationships, balancing between control and tolerance (Bowen & Mason, Citation2012), treating patients respectfully and being empathetic are pivotal professional skills that nurses should have when treating patients in challenging situations (Delaney & Johnson, Citation2006; Mason et al., Citation2008).

There are some limitations to our study that must be acknowledged. The included articles were only in the English language meaning that relevant articles in other languages might be excluded and valuable information lost. However, the systematic search using various suitable databases resulted in 21 articles which enabled data analysis and synthesis, resulting to relevant findings, can be mentioned as strengths of the study. In addition, the included articles’ quality was critically evaluated by three researchers using the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., Citation2018).

Relevance for clinical practice

This study benefits clinical practice in several ways. The three main findings were (1) Balancing between different care practices, (2) PICU as a challenging work environment, (3) Nursing interventions in PICU. These study results support the clinical practice by giving new ideas how to develop the PICU practices, designing new PICU areas and implementing new nursing interventions to PICU.

Based on the results, we need to further develop safety guidelines in clinical practice to ensure nurses’ and patients’ safety. In addition, to build the care into a more communicative direction may contribute to better quality of care in PICU units. In future, we can also develop PICUs’ physical features to ensure that patients have the needed privacy, but safety standards are taken care of. Benefits for clinical practice can be seen also in the educational approach: as we know that working in PICU units is demanding, we can create more up-to-date professional continuing education for nursing staff related to safety and nursing interventions. This study also benefits patients by increasing knowledge on therapeutic communication and collaboration with staff.

Further on, the results of this study lead us to pay more attention to human resourcing in PICUs, including staffing patterns, skill mix and staff -patient ratio. Special PICU guidelines to ensure occupational safety and patient safety are warranted as well as guidelines for the staff resources in PICU. Also, this review leads us to develop new psychiatric hospitals and design new units, considering PICU units to be more patient-friendly, by integrating exercise areas and spaces offering more privacy.

Based on the results, we need to further research on PICU’s use and effectiveness on larger scale studies. As there is trend to start modernizing psychiatric hospitals we need evidence based knowledge on PICU’s effects on safety to patients and staff. As well as, research on patients and staff’s perceptions on PICU’s.

Conclusion

PICU units seem to be challenging as a care and working environment for patients and nurses. However, the safety of PICUs is pivotal in ensuring high quality care for patients and occupational safety for nurses. PICU units should be developed in a way that patients’ autonomy, privacy and need for therapeutic communication are respected. Keeping strict rules and practices versus treating patients individually and using less coercive methods creates an ethical dilemma for nurses which should not be underrated.

Disclosure of interest

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ash, D., Suetani, S., Nair, J., & Halpin, M. (2015). Recover-based services in a psychiatric intensive care unit-the consumer perspective. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(5), 524–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215593397

- Bierbooms, J. J. P. A., Lorenz-Artz, C. A. G., Pols, E., & Bongers, I. M. B. (2017). Drie jaar high en intensive care: Evaluatie van ervaringen van cliënten en medewerkers en de effecten op gebruik van drang en dwang. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 59(7), 427–432.

- Björkdahl, A., Palmstierna, T., & Hansebo, G. (2010). The bulldozer and the ballet dancer: Aspects of nurses’ caring approaches in acute psychiatric intensive care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(6), 510–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01548.x

- Bos, M., Kool-Goudzwaard, N., Gamel, C. J., Koekkoek, B., & Van Meijel, B. (2012). The treatment of ‘difficult’ patients in a secure unit of a specialized psychiatric hospital: The patients’ perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(6), 528–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01827.x

- Bowen, M., & Mason, T. (2012). Forensic and non-forensic psychiatric nursing skills and competencies for psychopathic and personality disordered patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(23–24), 3556–3564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03970.x

- Bowers, L., Jeffery, D., Bilgin, H., Jarrett, M., Simpson, A., & Jones, J. (2008). Psychiatric intensive care units: A literature review. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 54(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764007082482

- Braham, L., Jones, D., & Hollin, C. R. (2008). The Violent Offender Treatment Program (VOTP): Development of a treatment program for violent patients in a high security psychiatric hospital. The International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 7(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2008.9914412

- Chukwujekwu, D. C., & Stanley, P. C. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of aggression among psychiatric in-patients at Jos University Teaching Hospital. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 14(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.84007

- Corsini, G., Trabucco, A., Respino, M., Magagnoli, M., Spiridigliozzi, D., Escelsior, A., & Amore, M. (2018). La gestione del tabagismo nei Servizi Psichiatrici di Diagnosi e Cura [Tabagism and its management in Italian Psychiatric Intensive Care General Hospital Units]. Rivista di Psichiatria, 53(6), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1708/3084.30764. PMID: 30667397.

- Crowhurst, N., & Bowers, L. (2002). Philosophy, care and treatment on the psychiatric intensive care unit: Themes, trends and future practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 9(6), 689–695. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00524.x

- Cullen, A. E., Bowers, L., Khondoker, M., Pettit, S., Achilla, E., Koeser, L., Moylan, L., Baker, J., Quirk, A., Sethi, F., Stewart, D., McCrone, P., & Tulloch, A. D. (2018). Factors associated with use of psychiatric intensive care and seclusion in adult inpatient mental health services. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000731

- Dawson, P., Kingsley, M., & Pereira, S. (2005). Violent patients within Psychiatric Intensive Care Units: Treatment approaches, resistance and the impact upon staff. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 1(01), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646405000087

- Delaney, K. R., & Johnson, M. E. (2006). Keeping the unit safe: Mapping psychiatric nursing skills. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 12(4), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390306294462

- Evans, R. E., & Petter, S. (2012). Identifying mitigating and challenging beliefs in dealing with threatening patients: An analysis of experiences of clinicians working in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 8(02), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646411000318

- Evatt, M., Scanlan, J. N., Benson, H., Pace, C., & Mouawad, A. (2016). Exploring consumer functioning in High Dependency Units and Psychiatric Intensive Care Units: Implications for mental health occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 63(05), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12290.

- Gentle, J. (1996). Mental health intensive care: The nurses’ experience and perceptions of a new unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24(6), 1194–1200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb01025.x

- Georgieva, I., De Haan, G., Smith, W., & Mulder, C. (2010). Successful reduction of seclusion in a newly development psychiatric intensive care unit. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 6(01), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646409990082

- Grassi, L., Peron, L., Marangoni, C., Zanchi, P., & Vanni, A. (2001). Characteristics of violent behaviour in acute psychiatric in-patients: A 5-year Italian study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 104(4), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00292.x

- Grove, S. K., Burns, N., & Gray, J. R. (2012). The practice of nursing research. In Appraisal, synthesis, and generating of evidence (7th ed.). Elsevier.

- Haugom, E. W., Ruud, T., & Hynnekleiv, T. (2019). Ethical challenges of seclusion in psychiatric inpatient wards: A qualitative study of the experiences of Norwegian mental health professionals. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4727-4

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boerdman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, G., Nivolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). User guide. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Hyde, C. E., Harrower-Wilson, C., & Morris, J. (1998). Violence, dissatisfaction and rapid tranquillisation in psychiatric intensive care. Psychiatric Bulletin, 22(8), 477–480. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.22.8.477

- Isaak, V., Vashdi, D., Bar-Noy, D., Kostisky, H., Hirschmann, S., & Grinshpoon, A. (2016). Enhancing the safety climate and reducing violence against staff in closed hospital wards. Workplace Health & Safety, 65(9), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916672478

- Iversen, V. C., Sallaup, T., Vaaler, A. E., Helvik, A.-S., Morken, G., & Linaker, O. (2011). Patients’ perceptions of their stay in a psychiatric seclusion area. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 7(01), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646410000075

- Keski-Valkama, A., Sailas, E., Eronen, M., Koivisto, A. M., Lönnqvist, J., & Kaltiala-Heino, R. K. (2010). The reasons for using restraint and seclusion in psychiatric inpatient care: A nationwide 15-year study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 136–144. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039480903274449

- Kontio, R., Joffe, G., Putkonen, H., Kuosmanen, L., Hane, K., Holi, M., & Välimäki, M. (2012). Seclusion and restraint in psychiatry: Patiets’ experiences and practical suggestions how to improve practices and use alternatives. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00301.x

- Lamothe, H., Lebain, P., Morello, R., & Brazo, P. (2019). Coercive stress in psychiatric intensive care unit: What link with insight? L’Encephale, 45(6), 488–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2019.05.010

- Lemmey, S. J., Glover, N., & Chaplin, R. (2013). Comparison of the quality of care in psychiatric intensive care units and acute psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 9(01), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646412000209

- Loubser, I., Chaplin, R., & Quirk, A. (2009). Violence, alcohol and drugs: The views of nurses and patients on psychiatric intensive care units, acute wards and forensic wards. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 5(01), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646408001386

- Mackay, I., Paterson, B., & Cassells, C. (2005). Constant or special observation of inpatients presenting a risk of aggression or violence: Nurses’ perceptions of the rules of engagement. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 12(4), 464–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00867.x

- Mason, T., Lovell, A., & Coyle, D. (2008). Forensic psychiatric nursing: Skills and competencies: I role dimensions. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15(2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01191.x

- McAllister, S., & McCrae, N. (2017). The therapeutic role of mental health nurses in psychiatric intensive care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(7), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12389

- Meehan, T., McIntosh, W., & Bergen, H. (2006). Aggressive behaviour in the high-secure forensic setting: The perceptions of patients. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00906.x

- Milan, S. (2011). Personal experiences and perspectives of psychiatric intensive care and recovery. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 7(2), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646410000191

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moylan, L. B., & Cullinan, M. (2011). Frequency of assault and severity of injury of psychiatric nurses in relation to the nurses’ decision to restrain. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(6), 526–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01699.x

- National Association of Psychiatric Intensive & Low Secure Units (NAPICU). (2014). National minimum standards for psychiatric intensive care in general adult services. Glasgow: NAPICU Administrative Office. https://napicu.org.uk/publications/national-minimum-standards/

- NHS. (2010). Intensive psychiatric care units. Overview report-June 2010. NHS.

- O’Brien, L., & Cole, R. (2004). Mental health nursing practice in acute psychiatric close-observation areas. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 13(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2004.00324.x

- O’Brien, A., Cramer, B., Rutherford, M., & Attard, D. (2013). A retrospective cohort study describing admissions to a London Trust’s PICU beds over one year: Do men and women use PICU differently? Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 9(1), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646412000167

- O’Brien, A., Tariq, S., Ashraph, M., & Howe, A. (2014). A staff self-reported retrospective survey of assaults on a psychiatric intensive care ward and attitudes towards assaults. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 10(02), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646413000241

- Pereira, S. M., Sarsam, M., Bhui, K., & Paton, C. (2005). The London Survey of Psychiatric Intensive Care Units: Psychiatric intensive care; patient characteristics and pathways for admission and discharge. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 1(01), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174264640500004X

- Price, O., Baker, J., Bee, P., & Lovell, K. (2018). The support-control continuum: An investigation of staff perspectives on factors influencing the success or failure of de-escalation techniques for the management of violence and aggression in mental health settings. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 77, 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.002

- Rooney, C. (2009). The meaning of mental health nurses experience of providing one-to-one observations: a phenomenological study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16, (1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01334.x

- Salzmann-Erikson, M. (2013). Limiting patients as a nursing practice in Psychiatric Intensive Care Units to ensure safety and gain control. Perspectives of Psychiatric Care, 51(4), 241–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12083

- Salzmann-Erikson, M. (2018). Moral mindfulness: The ethical concerns of healthcare professionals working in a psychiatric intensive care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(6), 1851–1860. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12494

- Salzmann-Erikson, M., Salzmann-Krikson, M., Lützén, K., Ivarsson, A.-B., & Eriksson, H. (2008). The core characteristics and nursing care activities in psychiatric intensive care units in Sweden. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 17(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2008.00517.x

- Salzmann-Erikson, M., & Söderqvist, C. (2017). Being subject to restrictions, limitations, and disciplining: A thematic analysis of individuals’ experiences in psychiatric intensive care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(7), 540–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1299265

- Schröder, A., & Björk, T. (2013). Patients’ judgements of quality of care in psychiatric observation and intensive in-patient care. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 9(02), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646412000313

- Shattell, M. M., Andes, M., & Thomas, S. P. (2008). How patients and nurses experience the acute care psychiatric environment. Nursing Inquiry, 15(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2008.00397.x

- Stevenson, G. S. (2013). A comparison of psychiatric nursing staff experience of, and attitudes towards, the psychiatric intensive care services in a Scottish health region. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 9(01), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742646412000222

- Stone, P. W. (2002). Popping the (PICO) question in research and evidence-based practice. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 15(3), 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1053/apnr.2002.34181

- Tyson, G. A., Lambert, G., & Beattie, L. (2002). The impact of ward design on the behaviour, occupational satisfaction and well-being of psychiatric nurses. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 11(2), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2002.00232.x

- Vaaler, A. E., Morken, G., & Linaker, O. M. (2005). Effects of different interior decorations in the seclusion area of a psychiatric acute ward. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 59(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480510018887

- Vaaler, A. E., Morken, G., Fløvig, J. C., Iversen, V. C., & Linaker, O. M. (2006). Effects of a psychiatric intensive care unit in an acute psychiatric department. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 60(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480600583472

- Vaaler, A. E., Iversen, V. C., Morken, G., Fløvig, J. C., Palmstierna, T., & Linaker, O. M. (2011). Short-term prediction of threatening and violent behaviour in an Acute Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit based on patient and environment characteristics. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-44

- Van Melle, A. L., Voskes, Y., de Vet, H. C. W., Van Der Meijs, J., Mulder, C. L., & Widdershoven, G. A. M. (2019). High and intensive care in psychiatry: Validating the HIC monitor as a tool for assessing the quality of psychiatric intensive care units. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 46(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0890-x

- Walsh-Harrington, S., Corrigall, F., & Elsegood, K. (2020). Is it worthwhile to offer a daily ‘bitesized’ recovery skills group to women on a psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU)?. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 16(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.20299/jpi.2019.017

- Ward, L., & Gwinner, K. (2015). Have you got what it takes? Nursing in a Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 10(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-08-2014-0021

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Winkler, D., Naderi-Heiden, A., Strnad, A., Pjrek, E., Scharfetter, J., Kasper, S., & Frey, R. (2011). Intensive care in psychiatry. European Psychiatry, 26(4), 260–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.10.008

- Wykes, T., & Carroll, S. (1993). Patient satisfaction with intensive care psychiatric services: Can it be assessed? Journal of Mental Health, 2(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638239309016969

- Wynaden, D., McGowan, S., Chapman, R., Castle, D., Lau, P., Headford, C., & Finn, M. (2001). Types of patients in a psychiatric intensive care unit. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(6), 841–845. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00953.x

- Zarea, K., Nikbakht-Nasrabadi, A., Abbaszadeh, A., & Mohammadpour, A. (2013). Psychiatric nursing as ‘different’ care: Experience of Iranian mental health nurses in inpatient psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01891.x