Abstract

Person-centred decision-making approaches in mental health care are crucial to safeguard the autonomy of the person. The use of these approaches, however, has not been fully explored beyond the clinical and policy aspects of shared and supported decision-making. The main goal is to identify and collate studies that have made an essential contribution to the understanding of shared, supported, and other decision-making approaches related to adult mental health care, and how person-centred decision-making approaches could be applied in clinical practice. A scoping review of peer-reviewed primary research was undertaken. A preliminary search and a main search were undertaken. For the main search, eight databases were explored in two rounds, between October and November 2022, and in September 2023, limited to primary research in English, Spanish or Portuguese published from October 2012 to August 2023. From a total of 12,285 studies retrieved, 21 studies were included. These research articles, which had mixed quality ratings, focused on therapeutic relationships and communication in decision-making (30%), patients’ involvement in treatment decision-making (40%), and interventions for improving patients’ decision-making engagement (30%). While there is promising evidence for shared decision-making in mental health care, it is important that healthcare providers use their communicational skills to enhance the therapeutic relationship and engage patients in the process. More high-quality research on supported decision-making strategies and their implementation in mental health services is also required.

Background

Decision-making is crucial in respecting the person’s right to make their own decisions while supporting their accountability in the process. According to the World Health Organization, (Citation2022), the ability to make decisions about one’s own life, including the choice of one’s own mental health care, is significant to a person’s autonomy and personhood (Tonelli & Sullivan, Citation2019). The most currently discussed person-centred approaches for decision-making in mental health care are shared decision-making and supported decision-making (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017).

Shared decision-making involves both the person and the mental health care provider. In shared decision-making, the person (often assisted by a member of their support network) brings expertise of their own personal values, goals, and preferences, while the health care provider contributes with their understanding of the health issue and available treatment options (Drake et al., Citation2009). Similarly, supported decision-making can help people make their own decisions about their mental health care while preserving their autonomy (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Supported decision-making ensures support for people whenever they require it, including accessibility to advocates and the provision of relevant information (World Health Organization, Citation2021). The main difference is that in supported decision-making, the decision-maker is always the person with a mental health issue (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Both concepts, shared decision-making and supported decision-making, have begun to arise in mental health research, policy, and practice when discussing person-centred decision-making in mental health care (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017). Although similar in meaning, the concepts have quite different origins (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017). Shared decision-making arises from health care services and is related to treatment decision-making (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017). Conversely, supported decision-making comes from the standpoint of human rights and disabilities, including persons with mental disorders (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017). Although incorporating decision-making strategies into mental health care is a promising strategy, comprehensive research and targeted treatments must be conducted to help enhance mental health care (Wills & Holmes-Rovner, Citation2006).

While the implementation of shared and supported decision-making in mental health services has been explored in the literature, the evidence-base remains limited (Davidson et al., Citation2015; Penzenstadler et al., Citation2020; Slade, Citation2017). The main areas related to supported decision-making implementation are in end-of-life care and intellectual and/or psychosocial disabilities (Davidson et al., Citation2015; Harding & Taşcıoğlu, Citation2018; Watson et al., Citation2017). Ethical and cultural challenges of decision-making implementation in mental health care have been identified, particularly about the tension between rights-based and duty-based frameworks related to patients and healthcare providers (Slade, Citation2017). The former framework refers mainly to respect of the patient’s human right to autonomy, whereas the latter framework is rooted in the ethical principle of beneficence, leading clinicians to apply a therapeutic regime when patients have impaired decisional capacity (Slade, Citation2017). A similar imbalance exists in institutional settings where healthcare providers ‘override’ the decisional process without patient involvement (Slade, Citation2017).

Two searches were undertaken in this review, a preliminary search to explore the existing literature in the topic, and the main research to find relevant studies. The topic for the preliminary search was the same of the main search, that is, adult decision-making in mental health care. The preliminary search was conducted before the actual review by using the search terms included in the search strategy below. The first or exploratory search of Medline, PROSPERO, the Joanna Briggs Institute of Evidence Synthesis, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews showed several published reviews of the literature in shared decision-making. These studies have been mostly focused on the clinical outcomes of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression, health service outcomes, and patient knowledge/involvement (Aoki et al., Citation2022; Marshall et al., Citation2021). A further focus of supported decision-making reviews was the development and implementation of this approach in mental health services (Davidson et al., Citation2015; Penzenstadler et al., Citation2020). Notwithstanding that, this exploratory or preliminary search revealed no review contained both terms plus a description of the decision process in psychiatry. For this reason, the objective of this scoping review is to identify and collate studies that have made an essential contribution to the understanding of shared, supported, and other decision-making approaches related to adult mental health care, and how person-centred decision-making approaches could be applied in clinical practice. For example, some people might consider family support and personal preferences when making decisions about their mental health care. A scoping review has been conducted because this tool is suitable for determining the breadth or depth of a body of literature on a particular subject by providing a clear picture of the amount of literature and studies that were accessible and an overview (wide or comprehensive) of their main points (Munn et al., Citation2018) The research questions posited were, what are the primary aspects of shared, supported, and other person-centred descriptions of decision-making in mental health care? And what are the most effective strategies to implement decision-making approaches in mental health practice?

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review—Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) checklist served as the basis for conducting and reporting this scoping review (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The key inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed literature of primary research published in English, Spanish or Portuguese relating to people aged 18 years and older, with mental illnesses and/or cognitive impairment, discussing two or more aspects of patient decision-making (e.g. pharmacologic treatment and family support), shared decision-making and/or supported decision-making in mental health care, aligned with patient-centred decision-making as stated by the author(s), and/or discussing at least one strategy of implementation of decision-making in mental health services.

Papers were excluded if they were literature reviews, letters to the editor, case studies and opinion letters. Research papers were also excluded if they were centred on caregiver decision-making on behalf of the individual, and/or other decision-making processes, such as clinical decision-making and surrogate decision-making, as both do not adhere to a person-centred decision-making approach.

Search strategy

The search method combined free text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) phrases. Databases searched for relevant and related literature were the Academic Search Complete, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was undertaken in two rounds, being the first conducted in November 2022 including only items published during the period of October 31, 2012, to October 31, 2022, limiting it to 10 years in consideration of changing evidence, policies, and legislation worldwide. The second search was conducted in September 2023 and encompassed the period between November 1, 2022, and August 31, 2023. The following search terms were applied: “decision-making” OR “decision making process” OR “shared decision making” OR “supported decision making” AND “mental health” OR “emotional health” OR “psychological health” AND adult* OR “middle aged” OR aged OR elderly AND implementation OR “implementation strategies” OR “implementation methods.”

The included citations were chosen for screening based on the title, abstract, and full text. Study records were managed in EndNoteTM 20 (The EndNote Team, Citation2013). Study selection and data extraction were undertaken with the Covidence systematic review application online (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2022). Data synthesis was conducted using thematic analysis, adopting an interpretative paradigm for interpreting the views of others through inductively organising study results into themes of related concepts (Braun, 2021). This scoping review did not require institutional ethical approval.

Separate title and abstract screening via Covidence were performed by two of the authors (author 1 and author 3), with author 2 mediating differences. After that, author 4 moderated the votes while author 1 and author 2 conducted full-text evaluations, after which the selected papers were extracted.

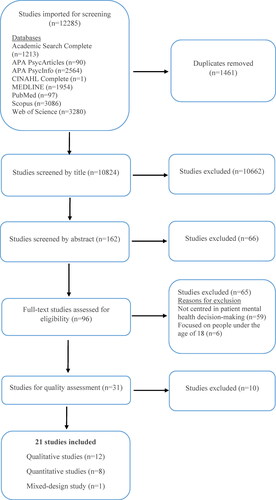

illustrates the process of article selection. Nine-thousand six hundred and ninety-five studies were initially eligible for inclusion, 8,301 of which were retained after removing 1,394 duplicates. After title and abstract screening, 8,213 records were excluded, leaving 88 studies for full-text screening. Upon exclusion of 62 studies, 26 were left for quality assessment.

Quality assessment

To ensure the quality of the studies, only scientific papers reported in peer-reviewed publications that had a pertinent sample for the phenomenon being examined and relevant study findings were retrieved. Before a decision was made regarding the inclusion of an article, two researchers read the whole text of each potential qualifying article. Discussions among the study team members were used to resolve disagreements. The selected papers were further assessed for quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 (Hong et al., Citation2018), and The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools—namely the Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies, Checklist for Cohort Studies, Checklist for Qualitative Research, Checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials, and Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2022). To apply the checklists, the researchers determined acceptable classifications as a team, namely “good,” “fair” and “poor.” Studies with no more than one item being not present or unclear were classified as of good quality, studies with up to three unclear or not present items received a “fair” classification, and those with more than three items which were unclear or not present were classified as of “poor” quality. Disagreements in the quality assessment were solved within the research team. Based on the methodology of the study, fifteen of the included studies were given a “good” quality rating whilst six received a “fair” rating (). The ten studies that received a “poor” quality rating were excluded, leaving 21 papers for inclusion in the final data synthesis ().

Table 2. Quality assessment of each article.

Data synthesis

provides a summary of the key findings of the included articles. For each of the areas of interest, data was condensed, organised, and compared on variables and sample characteristics in a matrix. Two methods of data comparison, data analysis and data display, were used to find patterns and themes in the data such as (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005).

Table 1. Summary of the characteristics of the selected studies.

Results

The 21 included studies addressed three main themes—therapeutic relationships and communication in decision-making, patient involvement in treatment decision-making, and interventions to improve patient decision-making engagement. Most studies (18) focused on shared decision-making and only one was focused on supported decision-making (Kokanović et al., Citation2018). The remaining four studies focused on informed decision-making and patient-centred decision-making (Hines et al., Citation2018), congruence in decision-making preferences regarding compulsory hospital admission (Morán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020), and treatment decision-making (Myers et al., Citation2019; Thomas et al., Citation2022). Seven studies were conducted in the USA, three studies in the United Kingdom, two studies each in Norway, Spain, and Germany, and one study each in Australia, Ethiopia, Japan, Sweden, and Switzerland. Twelve studies were qualitative, eight were quantitative and one was a mixed-design study.

Therapeutic relationship and communication in decision-making

Six of the included papers stressed the significance of dialogue and the therapeutic alliance for patient decision-making. Five papers were focused on shared decision-making and supported decision-making was the focus of only one study (Kokanović et al., Citation2018). A greater consumer-provided relationship, or the relationship between the patient and the healthcare professional, can be achieved by adopting a shared decision-making approach, with a higher level of patient involvement (Matthias et al., Citation2014). The length of the therapeutic relationship is important because longer relationships between the patient and healthcare provider lead patients to feel more comfortable in processes such as expressing disagreement (Matthias et al., Citation2014). The extent of patient involvement in shared decision-making discussions also depends on factors like the personal initiative of the patients to be engaged in the process, and the communication style of health care professionals (Gurtner et al., Citation2022). The best communication style to promote shared decision-making in a psychiatric inpatient setting is bidirectional, allowing the patient to express their concerns and questions while getting feedback from the professionals (Gurtner et al., Citation2022).

According to Haugom et al., (Citation2022), the main obstacles to shared decision-making were the reluctance of health professionals to offer patients their expected level of involvement and insufficient information about the course of their illness and treatment options. For psychiatric patients admitted into hospital involuntarily, communication issues between them and their physicians were found to be the main obstacles to shared decision-making, as well as the busy and noisy clinical ward environment where these interactions take place (Giacco et al., Citation2018). In this context, the ability of the healthcare provider is critical to foster a conversation characterised by trust, respect, clear guidance, and equality while involving family, partners, or friends, thus helping patients express their needs (Grim et al., Citation2016).

Similarly, there are further barriers and facilitators related to implementing supported decision-making (Kokanović et al., Citation2018). The main barriers were patient perceptions of impersonal interactions with mental health practitioners, impersonal care structures, long wait periods for appointments, stigma from professionals, and the erroneous assumption of patient incapacity in decision-making (Kokanović et al., Citation2018). Effective communication skills and empathic relationships with health care professionals were facilitators for implementing supported decision-making (Kokanović et al., Citation2018).

Patient involvement in treatment decision-making

The involvement of patients in treatment decision-making was the subject of nine of the included studies, seven of which are focused on shared decision-making, one explored informed decision-making and patient-centred decision-making (Hines et al., Citation2018) and one was focused on treatment decision-making (Myers et al., Citation2019). Engagement and active participation of the patient during the consultation with their psychiatrist is central for successful shared decision-making (Hamann et al., Citation2016). Additionally, respect and politeness, openness, and trust with their psychiatrist, gathering information and preparing for the consultation besides informing the psychiatrist and giving feedback are crucial (Hamann et al., Citation2016). Matthias et al., (Citation2012) present a typology to comprehend effective decision-making for people with mental illnesses and mental health professionals, and whether this process meets the criteria for shared decision-making. Their findings reveal that the process fails to meet these criteria because patient preferences were not considered in the final decisional outcome, even though both patients and health care providers often come to a resolution together when discussing an aspect of treatment (Matthias et al., Citation2012). Abate et al., (Citation2023) carried out an explanatory sequential mixed method study in a sample of 423 patients with mental illness, finding that nearly half of participants had low level of shared decision-making involvement during psychiatric treatment. Low shared decision-making was associated to several barriers such as poor social support, no community-based health insurance, and poor perceived compassionate care (Abate et al., Citation2023). Moreover, patients manifested concerns related to service quality, psychosocial factors like social support, and human resources (Abate et al., Citation2023). As a result of the low involvement, patients felt that in spite of having the knowledge to actively participate in shared decision-making, they were not always given the chance to do so, feeling that their opinions were neglected, and their autonomy invalidated (Sather et al., Citation2019). In this context, an individual care plan was seen as an important mechanism to alleviate and overcome the power imbalance between practitioners and patients (Sather et al., Citation2019).

Similar findings were described by Hines et al., (Citation2018), who conducted a cross-sectional study centred on informed decision-making and patient-centred decision-making, with a sample of 76 African-American participants. The authors found that only 9% of treatment choices for depression satisfied fundamental criteria for informed decision-making, meaning that the process was not person-centred (Hines et al., Citation2018). Risks and benefits were only presented in less than one of every six decisions, even though the nature of the decision was always discussed, and treatment alternatives were reviewed half of the time (Hines et al., Citation2018).

Different degrees of involvement in shared decision-making were preferred by patients (Mundal et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2014). Park et al., (Citation2014) assessed shared decision-making preferences in mental health treatment in a sample of 239 veterans diagnosed with a serious mental illness, finding that most patients preferred to be offered options and to be asked their opinions about treatment. More than half of patients preferred a passive role in decision-making by relying on their providers’ knowledge, letting their providers make final treatment decisions (Park et al., Citation2014). Greater preferences for participation have been found among African Americans, patients receiving an income for their work, with a college degree or higher education, with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia, and with a poorer therapeutic relationship with their prescribers (Park et al., Citation2014). Similarly, the preferences in decision-making varied according to gender, age group and educational level, with some groups of patients showing reluctance to accept pharmacological treatment whereas others remained unconcerned (Mundal et al., Citation2021). Young and middle-aged men tended to feel in control of their disease compared with older women who attributed the control of their disease to their psychiatrists (Mundal et al., Citation2021).

The involuntary use of mental health services in the context of patient involvement in shared decision-making has been explored by Morán-Sánchez et al., (Citation2020). The authors carried out a cross-sectional study, including 107 outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and a history of compulsory admission (Morán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020). They assessed congruence in decision-making experience and preferred style by using a control preference scale, finding that respecting the wishes of the person in decision-making is important in preventing compulsory admission (Morán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020).

Myers et al., (Citation2019) focused on factors that shaped treatment decision-making in young adults after an initial hospitalisation for psychosis, finding that a difficulty for patient involvement in decision-making was their multiple mental health-related concerns. Their main concerns were getting back to normal, insufficient mental health care on offer, police involvement in their pathway to care, feeling worse, and needing help with navigating strained relationships (Myers et al., Citation2019). Further concerns were independence in the future, paying for mental health care, distrusting mental health diagnoses, managing social pressure to use substances, and feeling disempowered by hospitalisation experiences (Myers et al., Citation2019).

Interventions for improving patient decision-making engagement

Interventions to enhance patient decision-making in mental health care were the focus of six of the included studies, with five focused on shared decision-making and one on treatment decision-making (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Aoki et al., (Citation2019) examined the experiences of 10 psychiatric outpatients of a three-stage shared decision-making intervention including first consultation, decision aid review at home, and second consultation. Patients described anticipatory anxiety to becoming involved in decision-making in the first consultation, shifting towards less decisional conflict and a more active involvement after the second consultation (Aoki et al., Citation2019). While at home, patients were able to access the information from the decision aids, giving them time to consider their options carefully and involving others (Aoki et al., Citation2019). Hamann et al., (Citation2020) conducted a cluster-randomised trial to examine if the approach called SDM-PLUS facilitated shared decision-making in acutely-ill psychiatric patients in inpatient settings. The results show that this approach led to higher perceived involvement in decision-making with a better therapeutic alliance and treatment satisfaction (Hamann et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the adoption of behavioural approaches like motivational interviewing for shared decision-making could be successful (Hamann et al., Citation2020). Conversely, the cluster randomised trial of Lovell et al., (Citation2018) showed that a shared decision-making intervention for community mental health services had no significant effects on patient perceptions of autonomy support, or other primary outcomes at six months of the intervention. The authors found significant effects on only one secondary outcome, and service satisfaction (Lovell et al., Citation2018).

Interventions should address the main barriers and facilitators for successful patient engagement in treatment decision-making (Thomas et al., Citation2022) and shared decision-making (Alegria et al., Citation2018; Farrelly et al., Citation2016). Adults in an early intervention psychosis program, for instance, may benefit from interventions designed to reduce decisional conflict, and decisions pertaining to treatment goals and life outcomes (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Interventions should address patient needs for a successful decision-making involvement, specifically facilitators and barriers (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Facilitators are obtaining information or knowledge, personal values being considered, time for decision-making and social support (Thomas et al., Citation2022). The main barriers were lack of internal resources, social factors, unappealing options, and insufficient information or knowledge about the available options (Thomas et al., Citation2022). For shared decision-making, further barriers were perceptions that shared decision-making was already done, ambivalence about care planning, limited availability of choices, and concerns of clinicians about the appropriateness of patient’s choices (Farrelly et al., Citation2016). In this context, an intervention of a joint crisis plan effectively addressed these barriers (Farrelly et al., Citation2016). Given that different cultural backgrounds between patients and clinicians can be a barrier for decision-making, a clinical intervention targeting a culturally diverse sample population can improve shared decision-making (Alegria et al., Citation2018). This shared decision-making intervention, focused on identifying resources, asking questions and communicating preferences, can be effective when the patient and clinician have different primary languages (Alegria et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify and collate studies that have made an essential contribution to the understanding of shared, supported, and other decision-making approaches related to adult mental health care, and how person-centred decision-making approaches could be applied in clinical practice. An in-depth analysis of 21 quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-design studies was conducted. The preliminary evidence suggests that person-centred decision-making in mental health care has the potential to improve patient experiences and health outcomes, compared to clinician-led decision-making. The general findings highlight the importance of the main facilitators, namely the therapeutic alliance and communication between the patient and health care professionals, as well as information sharing, patient agency, positive beliefs towards health services, support from others, and respect for patient wishes. The main barriers for decision-making participation are reluctance from professionals to involve patients in this process, communication issues, scarce information about treatments, perceptions of impersonal care and stigma. Nevertheless, the findings also show a large predominance of studies focused on shared decision-making, with little presence in the literature of other decision-making approaches, including supported decision-making. This review found implementation strategies for shared decision-making and one for treatment decision-making, but no for supported decision-making. The most effective strategies for embedding shared decision-making in mental health practice are focused on communication and the therapeutic alliance and should address barriers such as limited availability of choices, and concerns about patient decisional capacity. These strategies have been proven effective in both inpatient and outpatient settings, except for one strategy tested in a community mental health care setting. Similarly, interventions that aim to improve treatment decision-making must address the barriers while enhancing the decision-making facilitators, e.g. therapeutic alliance, information sharing, patient agency, and so forth.

The focus of the literature in shared decision-making is certainly important due to its multiple applications in different mental health care settings, given its relevance for the main emergent topics from this review, namely therapeutic relationship, patient involvement, and interventions for patient involvement in decision-making. The potential applications include patients in inpatient units (Giacco et al., Citation2018; Morán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020), participants with experiences in both inpatient and outpatient units (Hamann et al., Citation2016; Haugom et al., Citation2022), transition from the hospital to the community (Sather et al., Citation2019), recovery centres (Matthias et al., Citation2012), and outpatient clinics (Alegria et al., Citation2018; Aoki et al., Citation2019; Farrelly et al., Citation2016; Grim et al., Citation2016; Matthias et al., Citation2014; Mundal et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2014). As per the findings of this review, the main benefits of shared decision-making are a better patient-healthcare provider relationship (Matthias et al., Citation2014), patient engagement in the decision-making process (Hamann et al., Citation2016), lower anticipatory anxiety (Aoki et al., Citation2019), preventing compulsory hospital admission (Morán-Sánchez et al., Citation2020), and reduced decisional conflict (Thomas et al., Citation2022). Conversely, the main barriers for shared decision-making are reluctance to involve patients (Haugom et al., Citation2022), communication issues upon hospital admission (Giacco et al., Citation2018), and overlooking patient preferences (Matthias et al., Citation2012; Sather et al., Citation2019). One of the main reasons for these barriers in clinical practice could be the fact that patients with severe mental illness struggle to be seen as competent by healthcare providers, often feeling omitted from involvement in shared decision-making, with their needs and capabilities not being adequately recognised (Dahlqvist Jönsson et al., Citation2015). Having said that, acutely ill patients can be effectively engaged in shared decision-making due to the increased awareness of decisional ability that they maintain, while counteracting the negative impact of stigma (Scholl & Barr, Citation2017). This could help to counteract additional obstacles for shared decision-making such as self-stigma, perceived power imbalances, and a lack of confidence in their knowledge (Burns et al., Citation2021). Given that many decisions in mental health care are preference sensitive, respecting the patient’s wishes is the basis of a successful implementation of shared decision-making in mental health care settings, leading to favourable health outcomes (Simmons et al., Citation2010). Regarding research in shared decision-making, there is limited understanding of how to conduct studies where the healthcare professionals are directly involved in the delivery of shared decision-making in mental health care (Ramon et al., Citation2017). Addressing underexplored areas of shared decision-making implementation in mental health care could lead to more effective decision-making interventions and further inform the guidance of future policy, practice, and research (Ramon et al., Citation2017).

This review detected a significant gap in terms of the application and implementation of supported decision-making in mental health practice. Supported decision-making was the subject of only one study, with empathetic relationships being the main facilitators and highlighting the impersonal care and assumptions of patient decisional incapacity as the main barriers (Kokanović et al., Citation2018). Experiencing severe mental illness does not necessarily imply that patients cannot make decisions about their own health care, since they may be able to understand treatment alternatives and make decisions based on their genuine needs (Munjal, Citation2016). On the contrary, supported decision-making can be beneficial for people with severe intellectual disabilities through a very close relationship with the supporter to gain knowledge about the patient’s life history and preferences (Watson et al., Citation2017). This is due to one of the main benefits of supported decision-making, the consideration of patient’s human rights in areas like law, policy and clinical practice, reason why this approach should be inherently included in mental health care (Simmons & Gooding, Citation2017). Also, supported decision-making, alongside with antidepressants, can be beneficial for those with suicidal ideation via telehealth (O’Callaghan et al. Citation2022). However, one of the drawbacks is that supported decision-making is not always incorporated in health interventions due to obstacles like the insufficient clinical time from the healthcare professional to support the patient in making a decision, and a lack of resources, including human resources (Gordon et al., Citation2022). There is a critical need for exploration and use of supported decision-making in clinical practice to make it proactively inclusive, especially for those who experience discrimination and inequities (Gordon et al., Citation2022). The implementation is complex and requires time, resources, and attitude changes from care providers and patients, in processes like informed consent, decisional conflict, and prospective decision-making (Davidson et al., Citation2015). A literature review found that none of the studied implementation models for supported decision-making have followed the requirements from The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, adopted at the United Nations Assembly by many countries (Penzenstadler et al., Citation2020). This means that mental health practice differs, and implementation of supported decision-making remains unsatisfactory as a result (Penzenstadler et al., Citation2020). For these reasons, further research in the use and implementation of supported decision-making in mental health services is strongly required.

This review identified six studies where patient-centred decision-making interventions were explored, none of which was focused on supported decision-making. While most interventions centred in shared decision-making (Alegria et al., Citation2018; Aoki et al., Citation2019; Farrelly et al., Citation2016; Hamann et al., Citation2020) and one in treatment decision-making (Thomas et al., Citation2022) were proven to be effective, one intervention focused on shared decision-making did not yield the same results, meaning that greater investment of resources is required in community mental health care settings for a successful implementation (Lovell et al., Citation2018). These findings suggest that the evidence regarding the barriers for the implementation process of decision-making interventions is scarce, perpetuating the knowledge gap. The main barriers in decision-making preclude the operationalisation of person-centred care practices in mental health services, jeopardising the empowerment of patients in their decision-making (Smith et al., Citation2019). It is important to not only identify the main obstacles to decision-making but also the main causes of the maintenance and recurrence of these barriers in clinical mental health practice, optimising the strengths of all parties involved. For this reason, future research should explore practical solutions to overcome these barriers besides understanding how shared decision-making impacts adults with mental health and psychiatric disorders across all healthcare settings (Burns et al., Citation2021; Tambuyzer et al., Citation2014). Organisational, service, professional and operational policies, and guidelines should be reviewed to guarantee that they reflect the values and principles of a recovery approach, thus influencing mental health practice (Cusack et al., Citation2017). On this basis, a good leadership is the cornerstone of a successful implementation of person-centred decision-making, requiring the integration of a range of disciplines, such as behavioural science, psychology, communication, and economics (Scholl & Barr, Citation2017). Leaders must be facilitators by promoting, enabling, and supporting the process at all levels of the health system (Campos & Reich, Citation2019). For the healthcare team, this support encompasses the provision of resources, like training programs and adequate facilities to assist patients in mental health services provided in both inpatient and outpatient settings. A successful implementation of person-centred decision-making approaches in clinical practice could standardise the processes that comprise the therapeutic relationship.

The therapeutic relationship between the patient and the health care provider are based on therapeutic communication. The studies in this review support the idea that communication in decision-making can be both a challenge and a potential. The challenge comes with the communication barriers that arise in the therapeutic relationship, where clinicians may unilaterally decide the mental health treatments without consulting the patient through a process of shared decision-making (Younas et al., Citation2016). Similarly, the quality of the therapeutic relationship with mental health nurses is an issue of great concern for patients, the reason being mainly the limited time that nurses spend with them (Moyo et al., Citation2022). The rise of health care system demands challenge the therapeutic relationship in nursing, potentially delivering suboptimal mental health care to patients with complex comorbidities and life situations (Harris & Panozzo, Citation2019). Consequently, patients perceive disenchantment, uncertainty and not being engaged in treatment and medication decision-making as the main barriers to decision-making (O'Driscoll et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, effective communication in the therapeutic relationship has the potential to ensure patient participation in decision-making, which is the cornerstone of this relationship (O'Driscoll et al., Citation2014). This demonstrates the need for training health care providers in communication skills to establish a therapeutic alliance that promotes patient decision-making (Ashoorian & Davidson, Citation2021). Developing communication skills to meet the challenges that come with the therapeutic relationship between the health care provider and the patient should therefore be mandatory for those helping mental health patients be autonomous, providing them with opportunities to engage in mental health care decision-making. Addressing the needs of patients in the therapeutic relationship is fundamental for delivering individualised care, thus enhancing patient decision-making and the quality of nursing care in mental health care settings.

Limitations

This review has important limitations. Primarily, although most of the included studies met the inclusion criteria, when interpreting the findings, it should be done with caution as seven studies of just fair methodological quality were included. Having said that, these studies were included as they were relevant in understanding patient decision-making in mental health care. Lastly, papers published in languages other than English, Spanish and Portuguese were not considered for the review, potentially excluding studies that could have helped to better understand decision-making in mental health care.

Conclusions

The evidence from this scoping review of the peer-reviewed literature underscores the importance of supported person-centred decision-making approaches, which may positively impact outcomes like patient involvement in decision-making and satisfaction with care. There is substantial research in shared decision-making and other treatment-related decision-making approaches in mental health care, whereas supported decision-making requires further attention. The critical aspects for shared, supported and other decision-making approaches are communication, information provision, social and professional support, patient perceptions of care, misconceptions about patient decisional capacity, and the willingness of health care providers to involve patients in decision-making. The most successful strategies for shared decision-making and other patient decisional approaches have incorporated all these areas in the tested interventions, leading to better outcomes. On the contrary, the main barriers and facilitators involved in supported decision-making as well as the implementation of this approach in mental health services remain unexplored.

Given the potential of supported decision-making in embedding human rights in mental health care, especially for those with severe mental illness, supported decision-making interventions should be the focus of future inquiry. Likewise, for all person-centred decisional approaches, there is potential for these strategies to be explored, specifically around implementation in mental health services in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Therefore, a recommendation for nursing practice is conducting further high-quality research with the purpose of exploring innovative decision-making approaches to make this process more integrative, comprehensive, and pertinent to the needs of the individual. A further focus of future research should be the complex implementation challenges of person-centred decision-making in mental health practice, which outcomes could lead to improvements in the quality of nursing care.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abate, A. W., Desalegn, W., Teshome, A. A., Chekol, A. T., & Aschale, M. (2023). Level of shared decision making and associated factors among patients with mental illness in Northwest Ethiopia: Explanatory sequential mixed method study. PLoS One, 18(4), e0283994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283994

- Alegria, M., Nakash, O., Johnson, K., Ault-Brutus, A., Carson, N., Fillbrunn, M., Wang, Y., Cheng, A., Harris, T., Polo, A., Lincoln, A., Freeman, E., Bostdorf, B., Rosenbaum, M., Epelbaum, C., LaRoche, M., Okpokwasili-Johnson, E., Carrasco, M., & Shrout, P. E. (2018). Effectiveness of the DECIDE interventions on shared decision making and perceived quality of care in behavioral health with multicultural patients a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4585

- Aoki, Y., Furuno, T., Watanabe, K., & Kayama, M. (2019). Psychiatric outpatients’ experiences with shared decision-making: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 12(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2019.1612212

- Aoki, Y., Yaju, Y., Utsumi, T., Sanyaolu, L., Storm, M., Takaesu, Y., Watanabe, K., Watanabe, N., Duncan, E., & Edwards, A. G. (2022). Shared decision-making interventions for people with mental health conditions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11(11), CD007297. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007297.pub3

- Ashoorian, D. M., & Davidson, R. M. (2021). Shared decision making for psychiatric medication management: A summary of its uptake, barriers and facilitators. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 43(3), 759–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01240-3

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage Publications.

- Burns, L., da Silva, A. L., & John, A. (2021). Shared decision-making preferences in mental health: Does age matter? A systematic review. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 30(5), 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1793124

- Campos, P. A., & Reich, M. R. (2019). Political analysis for health policy implementation. Health Systems and Reform, 5(3), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2019.1625251

- Cusack, E., Killoury, F., & Nugent, L. E. (2017). The professional psychiatric/mental health nurse: Skills, competencies and supports required to adopt recovery-orientated policy in practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(2-3), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12347

- Dahlqvist Jönsson, P., Schön, U. K., Rosenberg, D., Sandlund, M., & Svedberg, P. (2015). Service users’ experiences of participation in decision making in mental health services. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(9), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12246

- Davidson, G., Kelly, B., Macdonald, G., Rizzo, M., Lombard, L., Abogunrin, O., Clift-Matthews, V., & Martin, A. (2015). Supported decision making: A review of the international literature. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 38, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2015.01.008

- Drake, R. E., Cimpean, D., & Torrey, W. C. (2009). Shared decision making in mental health: Prospects for personalized medicine. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(4), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.4/redrake

- Farrelly, S., Lester, H., Rose, D., Birchwood, M., Marshall, M., Waheed, W., Henderson, R. C., Szmukler, G., & Thornicroft, G. (2016). Barriers to shared decision making in mental health care: Qualitative study of the joint crisis plan for psychosis. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 19(2), 448–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12368

- Giacco, D., Mavromara, L., Gamblen, J., Conneely, M., & Priebe, S. (2018). Shared decision-making with involuntary hospital patients: A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. BJ Psych Open, 4(3), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.6

- Gordon, S., Gardiner, T., Gledhill, K., Tamatea, A., & Newton-Howes, G. (2022). From substitute to supported decision making: Practitioner, community and service-user perspectives on privileging will and preferences in mental health care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106002

- Grim, K., Rosenberg, D., Svedberg, P., & Schön, U. K. (2016). Shared decision-making in mental health care-a user perspective on decisional needs in community-based services. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30563. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.30563

- Gurtner, C., Lohrmann, C., Schols, J. M. G. A., & Hahn, S. (2022). Shared decision making in the psychiatric inpatient setting: An ethnographic study about interprofessional psychiatric consultations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3644. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/6/3644 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063644

- Hamann, J., Holzhüter, F., Blakaj, S., Becher, S., Haller, B., Landgrebe, M., Schmauß, M., & Heres, S. (2020). Implementing shared decision-making on acute psychiatric wards: A cluster-randomized trial with inpatients suffering from schizophrenia (SDM-PLUS). Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e137, Article e137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000505

- Hamann, J., Kohl, S., McCabe, R., Bühner, M., Mendel, R., Albus, M., & Bernd, J. (2016). What can patients do to facilitate shared decision making? A qualitative study of patients with depression or schizophrenia and psychiatrists. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(4), 617–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1089-z

- Harding, R., & Taşcıoğlu, E. (2018). Supported decision-making from theory to practice: Implementing the right to enjoy legal capacity. Societies, 8(2), 25. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/8/2/25 https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8020025

- Harris, B. A., & Panozzo, G. (2019). Therapeutic alliance, relationship building, and communication strategies-for the schizophrenia population: An integrative review. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.08.003

- Haugom, E. W., Stensrud, B., Beston, G., Ruud, T., & Landheim, A. S. (2022). Experiences of shared decision making among patients with psychotic disorders in Norway: A qualitative study [Article]. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1):192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03849-8

- Hines, A. L., Roter, D., Ghods Dinoso, B. K., Carson, K. A., Daumit, G. L., & Cooper, L. A. (2018). Informed and patient-centered decision-making in the primary care visits of African Americans with depression. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.07.027

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., & Nicolau, B. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright, 1148552(10)

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2022). Critical appraisal tools. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

- Kokanović, R., Brophy, L., McSherry, B., Flore, J., Moeller-Saxone, K., & Herrman, H. (2018). Supported decision-making from the perspectives of mental health service users, family members supporting them and mental health practitioners. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(9), 826–833. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418784177

- Lovell, K., Bee, P., Brooks, H., Cahoon, P., Callaghan, P., Carter, L.-A., Cree, L., Davies, L., Drake, R., Fraser, C., Gibbons, C., Grundy, A., Hinsliff-Smith, K., Meade, O., Roberts, C., Rogers, A., Rushton, K., Sanders, C., Shields, G., Walker, L., & Bower, P. (2018). Embedding shared decision-making in the care of patients with severe and enduring mental health problems: The EQUIP pragmatic cluster randomised trial. PLoS One, 13(8), e0201533. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201533

- Marshall, T., Stellick, C., Abba-Aji, A., Lewanczuk, R., Li, X. M., Olson, K., & Vohra, S. (2021). The impact of shared decision-making on the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders: Systematic review [Review]. BJPsych Open, 7(6), e189. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1028

- Matthias, M. S., Fukui, S., Kukla, M., Eliacin, J., Bonfils, K. A., Firmin, R. L., Oles, S. K., Adams, E. L., Collins, L. A., & Salyers, M. P. (2014). Consumer and relationship factors associated with shared decision making in mental health consultations. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(12), 1488–1491. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300563

- Matthias, M. S., Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., & Frankel, R. M. (2012). Decision making in recovery-oriented mental health care [Article. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35(4), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.2975/35.4.2012.305.314

- Morán-Sánchez, I., Bernal-López, M. A., & Pérez-Cárceles, M. D. (2020). Compulsory admissions and preferences in decision-making in patients with psychotic and bipolar disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(5), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01809-4

- Moyo, N., Jones, M., Kushemererwa, D., Arefadib, N., Jones, A., Pantha, S., & Gray, R. (2022). Service user and carer views and expectations of mental health nurses: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11001. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711001

- Mundal, I., Lara-Cabrera, M. L., Betancort, M., & De las Cuevas, C. (2021). Exploring patterns in psychiatric outpatients’ preferences for involvement in decision-making: A latent class analysis approach. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03137-x

- Munjal, S. (2016). Don’t assume that psychiatric patients lack capacity to make decisions about care. Current Psychiatry, 15(4), e4–e6. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84971574744&partnerID=40&md5=b7c2957b0f69c2f767044e93fae7eda4

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Myers, N., Sood, A., Fox, K. E., Wright, G., & Compton, M. T. (2019). Decision making about pathways through care for racially and ethnically diverse young adults with early psychosis. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 70(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700459

- O’Callaghan, E., Mahrer, N., Belanger, H. G., Sullivan, S., Lee, C., Gupta, C. T., & Winsberg, M. (2022). Telehealth-Supported decision-making psychiatric care for suicidal ideation: Longitudinal observational study. JMIR Formative Research, 6(9), e37746. https://doi.org/10.2196/37746

- O'Driscoll, W., Livingston, G., Lanceley, A., A’ Bháird, C. N., Xanthopoulou, P., Wallace, I., Manoharan, M., & Raine, R. (2014). Patient experience of MDT care and decision-making. Mental Health Review Journal, 19(4), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-07-2014-0024

- Park, S. G., Derman, M., Dixon, L. B., Brown, C. H., Klingaman, E. A., Fang, L. J., Medoff, D. R., & Kreyenbuhl, J. (2014). Factors associated with shared decision–making preferences among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(12), 1409–1413. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400131

- Penzenstadler, L., Molodynski, A., & Khazaal, Y. (2020). Supported decision making for people with mental health disorders in clinical practice: A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 24(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2019.1676452

- Ramon, S., Brooks, H., Rae, S., & O’Sullivan, M.-J. (2017). Key issues in the process of implementing shared decision making (DM) in mental health practice. Mental Health Review Journal, 22(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-01-2017-0006

- Sather, E. W., Iversen, V. C., Svindseth, M. F., Crawford, P., & Vasset, F. (2019). Patients’ perspectives on care pathways and informed shared decision making in the transition between psychiatric hospitalization and the community. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(6), 1131–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13206

- Scholl, I., & Barr, P. J. (2017). Incorporating shared decision making in mental health care requires translating knowledge from implementation science. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(2), 160–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20418

- Simmons, M. B., & Gooding, P. M. (2017). Spot the difference: Shared decision-making and supported decision-making in mental health. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 34(4), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2017.59

- Simmons, M., Hetrick, S., & Jorm, A. (2010). Shared decision-making: Benefits, barriers and current opportunities for application. Australasian Psychiatry: Bulletin of Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, 18(5), 394–397. https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2010.499944

- Slade, M. (2017). Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 16(2), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20412

- Smith, C. A., Chang, E., Gallego, G., Khan, A., Armour, M., & Balneaves, L. G. (2019). An education intervention to improve decision making and health literacy among older Australians: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1143-x

- Tambuyzer, E., Pieters, G., & Van Audenhove, C. (2014). Patient involvement in mental health care: One size does not fit all. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 17(1), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00743.x

- The EndNote Team. (2013). EndNote. In (Version EndNote 20) [64-bit]. Clarivate.

- Thomas, E. C., Suarez, J., Lucksted, A., Siminoff, L., Hurford, I., Dixon, L., O'Connell, M., & Salzer, M. (2022). Treatment decision-making needs among emerging adults with early psychosis [Article. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 16(1), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.13134

- Tonelli, M. R., & Sullivan, M. D. (2019). Person-centred shared decision making. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(6), 1057–1062. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13260

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2022). Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation. www.covidence.org

- Watson, J., Wilson, E., & Hagiliassis, N. (2017). Supporting end of life decision making: Case studies of relational closeness in supported decision making for people with severe or profound intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 30(6), 1022–1034. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12393

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Wills, C. E., & Holmes-Rovner, M. (2006). Integrating decision making and mental health interventions research: research directions. Clinical Psychology: A Publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 13(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00002.x

- World Health Organization. (2021). Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030. WHO.

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. WHO.

- Younas, M., Bradley, E., Holmes, N., Sud, D., & Maidment, I. D. (2016). Mental health pharmacists views on shared decision-making for antipsychotics in serious mental illness. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(5), 1191–1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0352-z