Abstract

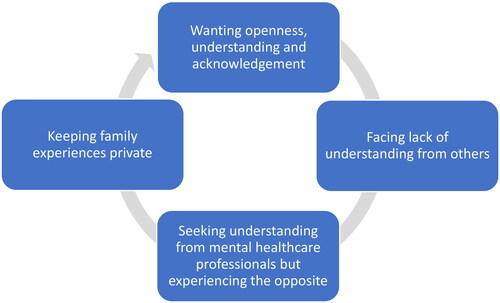

Not only people suffering from severe mental illness (SMI) but also their family members experience stigma. Relatives are met with negative attitudes from healthcare professionals, which adds to the problem. This Swedish study employed a qualitative inductive explorative design in the analysis of written free-text responses from 65 persons who completed a questionnaire for relatives of persons with SMI. The overarching theme, “A vicious circle of hope and despair”, was elaborated by four categories which formed a vicious circle: “Wanting openness, understanding and acknowledgement”; “Facing a lack of understanding from others”; “Seeking understanding from mental healthcare professionals but experiencing the opposite”; and “Keeping family experiences private.” If this vicious circle of family stigma is to be broken, measures are needed for both relatives and health care professionals.

Background

People with severe mental illness (SMI) are probably the most stigmatized by society today (Johnstone, Citation2001). Stigma has been defined as the mark that distinguishes someone as discredited on the basis of e.g. ethnicity, physical characteristics, or mental illness (Goffman, Citation1963). A US-based review highlighted common public beliefs about people with mental illness that included incompetence, and violent and criminal behaviors (Parcesepe & Cabassa, Citation2013). Half of the relatives of people diagnosed with schizophrenia in a Swedish study reported that their ill next-of-kin had been stigmatized (Allerby et al., Citation2015). A review of the literature from Latin America and the Caribbean (Mascayano et al., Citation2016), showed similar findings, and also highlighted the feeling of social exclusion experienced by people with mental illness. A review on healthcare professionals’ attitudes showed that clinical decisions were favorable to people with mental illness in only 21% of the findings (Crapanzano et al., Citation2023).

Several reviews demonstrate that negative attitudes toward individuals with mental illness contribute to feelings of being stigmatized in close relatives (Reupert et al., Citation2021; Shi et al., Citation2019; Yin et al., Citation2020). This phenomenon has been termed stigma by association, courtesy stigma (Bos et al., Citation2013; Goffman, Citation1963; Pryor et al., Citation2012; van der Sanden et al., Citation2014), or affiliate stigma (Shi et al., Citation2019). Larson and Corrigan (Larson & Corrigan, Citation2008) introduced the concept of family stigma, which can be defined as the prejudice and discrimination experienced by relatives’ associations with their next of kin with mental illness. This term will be applied for the purpose of the current article. As we live intertwined lives (Weimand, Citation2012), family stigma is closely connected with the stigma directed at the person in the family who has a mental illness. Stuart et al. (Heather Stuart et al., Citation2008; H. Stuart et al., Citation2008) showed that people with mental illness as well as their family members experience that stigma impacts negatively on quality of life, family relations, social contacts, and self-esteem. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis (Shi et al., Citation2019) identified psychosocial correlates of affiliate stigma in family caregivers of people with mental illness family including burden, depression, stress, and distress.

In recent years, the complex meaning of stigma among relatives of people with SMI has been investigated in two qualitative reviews (Yin et al., Citation2020) with 20 studies included, and (Manesh et al., Citation2023) with 16 studies included. Both reviews showed that relatives had experiences of stigmatization related to society’s negative view of mental illness, based on a lack of information and knowledge from, among other things, the media. Further, relatives’ social networks could also contribute to stigmatization, resulting in feelings of being labeled and excluded. Feeling stigmatized by social networks could lead to fewer social contacts and smaller networks, and isolation. Stigma brought on psychological reactions including shame, guilt, powerlessness, and emotional burden. The reviewed studies emanated from all parts of the world, primarily from Europe and Asia, but none originated from the Nordic region. There are, however, several quantitative studies from Sweden and Norway that explore family stigma. Results are mixed regarding the prevalence of family stigma. Relatives of persons diagnosed with schizophrenia took part in a Swedish questionnaire study about family stigma and only a fifth reported that they had been stigmatized and avoided situations that might elicit stigma (Allerby et al., Citation2015). In a more recent Swedish study, approximately one-third of the participants reported that stigma had negatively affected their quality of life (Sjöström et al., Citation2021). A partial explanation for the disparity could be that the former study was based in outpatient care and involved relatives of persons on oral antipsychotics. The other Swedish study recruited family members of people with SMI, regardless of care setting and treatment type. While results of both studies should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small number of participants and possible recruitment bias., prevalence figures for family stigma were rather low compared to reports from other parts of the world (Ebrahim et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2020). One reason for this might be that family members in Sweden tend to spend less time in a caregiver role compared to many other countries where health care services for persons with SMI may be less readily available. Another unexpected finding of the study of Sjöström and colleagues (Sjöström et al., Citation2021) was that almost three quarters of the participants reported that they did share their situation with relatives and friends. This finding contrasts somewhat with those of an earlier qualitative study set in Sweden (Graneheim & Åström, Citation2016) in which relatives told that they kept their situation a secret from friends.

In addition to relatives’ experiences of stigma in relation to their social networks, numerous Nordic studies (Ewertzon et al., Citation2011; Ewertzon et al., Citation2010; Johansson et al., Citation2019; Johansson et al., Citation2015) have captured relatives’ experiences of being approached by care professionals in a disrespectful manner; family members expressed feelings of alienation when in contact with mental health care professionals. However, there are also some studies that relate positive experiences of encounters with mental health services. One of these, set in Norway, investigated this phenomenon in the context of Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), in which a multidisciplinary professional team that includes the patient and their social network cooperate to develop a treatment plan based on individual needs (Weimand et al., Citation2018). The other study (Sjöström et al., Citation2021) included relatives who had taken part in Resource Groups Assertive Community Treatment (RACT), which is ACT with the addition of a Resource Group.

Given the relatively high availability of health care for persons with SMI in the Nordic countries, taken together with ongoing developments in the care and treatment of SMI in the region, it would be of interest to qualitatively investigate relative’s experiences of stigma, by both social networks and society, including health services in a Swedish context. Such a study can be of value to mental health professionals as well as those positioned to develop and implement new health care strategies for people with SMI. Hence, the aim of this study was to investigate how relatives with a next of kin treated for SMI experience family stigma and how they strive to handle stigmatization in a Swedish context.

Materials and methods

Design

A qualitative inductive explorative study was performed.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Research Committee in Gothenburg, No. T112-18, ad 151-17.

Recruitment procedures, sample, and data collection

The present study is part of a larger survey with the aim of investigating relatives’ encounters with mental health services, family burden and family stigma (Sjöström et al., Citation2021). A total of 139 relatives participated in the survey, and of those, 65 (48%) were included in the present study. Recruitment was carried via 1) mental care health care providers (Sahlgrenska University Hospital’s nine psychosis outpatient units and Skaraborg Hospital’s four outpatient units and one psychosis inpatient unit and 2) two NGOs: the Swedish Schizophrenia Fellowship and the Association for Psychiatric Co-operation in Skaraborg.

Inclusion criteria were adult (>18 years old) relatives of adult next of kin who were in contact with mental healthcare services due to SMI. Relatives were defined as persons within the immediate family, other close relatives, or other important persons, such as friends or neighbors. SMI was defined as a psychiatric disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially influences or limits in daily life. Participants must have sufficient Swedish language capability to understand the study information and questionnaires. The study population included relatives from 13 psychosis outpatient units, one psychosis inpatient unit and two non-governmental organizations (NGOs): the Swedish Schizophrenia Fellowship and the Association for Psychiatric Cooperation in the Western Götaland Region of Sweden. Participants’ demographics varied ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n = 65).

Data collection took place from October 1, 2017, to December 31, 2018. Information about the study was provided by case managers and by posters at the participating units and carer organizations. Interested relatives gave their email address and phone number to the case manager, who sent the contact information to the research assistant. The research assistant sent a self-report postal questionnaire and an informed consent form to those who had agreed to take part in the study. Those who did not return the questionnaire received one postal reminder.

In the present study the open-ended questions with spaces for free text responses from the structured questionnaire Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences (ISE, family version) was used (Heather Stuart et al., Citation2008). Participants were asked to describe their experiences of family stigma, and how they dealt with family stigma. In total, the 65 participants provided 46 pages with written responses.

Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis, inspired by Graneheim and Lundman (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004), was used to describe the relatives’ experiences of family stigma and how they strive to handle, or to prevent stigmatization. The numerous lines of free text regarding the two research questions were considered the unit of analysis. Participants’ comments were transcribed verbatim, and the text was read repeatedly by the research team to obtain an overview and general impression. The analysis was performed by identifying meaning units, each of which were labeled with a code. Patterns were continuously sought within the codes. In the next step we compared the codes and an initial grouping based on similarities and differences was performed. Up to this stage, the QRS NVivo 12 was utilized as a data analysis tool. After going back and forth between codes, grouping and the written responses, groups with similar content were sorted into the presented categories. As the final step in the analysis process, the underlying meaning of the text was closely scrutinized to identify an overall theme (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). During the entire analysis process, the research team discussed each step carefully, and whenever doubts aroused, the data was reviewed until mutual understanding was reached.

Results

A vicious circle of hope and despair

This overall theme revolves around being thrown back and forth between hope and despair regarding experiencing, and striving to decrease, family stigma, which was central to the participants’ narratives of their situation as a relative to a next of kin suffering from SMI. The overall theme comprised four categories: “Wanting openness, understanding and acknowledgement”; “Facing a lack of understanding from others”; “Seeking understanding from mental healthcare professionals but experiencing the opposite”; “Keeping family experiences private.” visualizes how these categories contribute to a vicious circle when the relative’s struggle to overcome family stigma fails. Included in the categories are descriptions of how they consistently strive to handle the family stigma, and how these attempts ultimately end up where they started—with an unmet need for openness, understanding and acknowledgement from those nearby as well as from society at large.

Figure 1. “A vicious circle of hope and despair.” Next of kin’s experiences and handling of family stigma related to severe mental illness in a family member.

Wanting openness, understanding and acknowledgement

In this category, the participants clearly describe that they first and foremost want to be able to be open about the situation they experience with a next of kin who has an SMI. The participants also stressed that they valued the principle of talking openly about the situation and sharing their knowledge, which they hoped might inform the general public as well as decision-makers. Following this principle was an emphasis on the importance of standing up for fellow human beings with mental illness, to speak out for the equal and unique value of all people. This would include to normalize and to break the existing taboos around mental illness and to not be ashamed of having a next of kin with mental illness. One of the participants expressed that “…the more that’s written [about mental illnesses], the more normalization. The more normalization, the less stigmatization.” Participants stressed the importance of spending time together with their ill next of kin in various social settings. Some made a point out of what they considered to be essential; the value of the next of kin being clean and well-dressed in such occasions, in order to counter stigma. Furthermore, the participants clearly expressed that the family must adapt to the new family situation when a family member struggles with mental illness.

… the shock and chaos which everyone with a psychosis may experience… structure, frameworks, peace and quiet, and faith in the future are needed. This can be created through education, participation, warmth, a pleasant approach, patience, respect, and support.

Some described that they tried to maintain family life as similar as possible to the way it was before their next of kin became ill. Albeit some friends remained close, the participants commonly expressed how they had to be persistent about explaining their situation to their friends, "family ties are strengthened, therefore we all fight against these prejudices.” Those who were NGO members emphasized the importance of receiving support, as well as the opportunity to provide support for others in the same situation. Several expressed the wish to contribute to reduce societal ignorance and prejudice regarding mental illness: "Once I get the opportunity, I speak and act for the rights of my loved ones.” While the participants described how they felt the responsibility to act against stigma, they also found it pivotal that research within the theme of family stigma should be carried out. Furthermore, they emphasized education about mental illness as a right step in removing the taboo that still prevails. The relatives’ suggestions for reducing family stigma are summed up in spreading knowledge, providing support and showing respect, both for the ill person and their family members.

Facing a lack of understanding from others

Attempts to be open about their family situation did not always lead to the desired result, and this can be summarized in the category “Facing lack of understanding from others,” including from society at large. The lack of understanding concerned both the situation of the next of kin with SMI, as well as the relative’s own situation.

Trying to share their experiences about the next of kin’s mental illness could give rise to comments that were directly negative from some, and more subtle responses with stigmatic connotations from others. Ignorance, as well as content experienced as being unsympathetic or unempathetic, were frequently described, such as "you just have to pull yourself together," "it’s stupid to give support" and questions like "are you ashamed?.” One participant expressed that such statements could lead to social isolation:

The courage to go out together with our son often fails us because of people’s misunderstandings. When I tell people that he has got a psychosis, their attitude completely changes. As if I mentioned a plague!

There were several descriptions of how friends had withdrawn or disappeared. The participants described that in their opinion, their friends’ ignorance about mental illness probably meant that they felt uncomfortable and frightened, and that they did not want to visit if their next of kin with SMI was present. Sometimes, people outside of the close family could treat the affected person and other family members differentially, which was hurtful both on their own behalf and on behalf of the person concerned. For example, in social contexts, the affected person could be “forgotten” or ignored, or not spoken to.

Seeking understanding from mental healthcare professionals but experiencing the opposite

The relatives’ need for collaboration with mental health professionals in connection with the treatment of their next of kin with SMI was great, especially considering their feelings of the lack of understanding from other family members, friends, and society as a whole. In addition to the fact that they need support for their own part, they described how they also want to be met with respect and interest considering the competence and knowledge they possess of how the mental illness affects their next of kin. Several participants lived around the clock with their ill next of kin and believed that they could positively influence the situation, if only the mental health professionals would listen to them. In particular, they described the importance of meeting acknowledgement from the professionals regarding their beliefs that people can recover—“come back”—from an SMI. Despite this, relatives experienced exclusion from the professional care, and in fact having to fight hard to be listened to and understood at all. One participant expressed that this made the recovery of their mentally ill next of kin more difficult.

It’s not my intention to question the staff’s competence, but no one knows my partner as well as I—and I know what works. When you’re not listened to and doctors and other staff (are) running their own race—I become so desperate, since my partner’s condition deteriorates, and the recovery becomes unnecessarily long and challenging. Our situation is already difficult enough and being constantly run over only makes it worse.

Several expressed that it had been energy-consuming to monitor that "the health care professionals do what they are supposed to" and to get them to see the picture of the illness that the family has seen for years. Several felt alone and left without support or understanding of "what it’s like as a relative to live in the middle of that.”

From the participants’ descriptions we found that not being taken seriously and not having the opportunity to collaborate with the professionals regarding their family member’s situation negatively affected their trust in the mental health professionals. Feelings of exclusion led to negative thoughts about health professionals’ assessment of them as relatives. Such thoughts about stigmatizing behavior from healthcare professionals were further explained by the participants as doubts about whether they could trust that these professionals took their input, views, and concerns seriously and handled them professionally. One mother put it this way:

Instead of getting relief and support, they [the staff] tell him not to contact me… it created even more despair and sadness in me. I want to be a mother, support, etc…. (be) able to spend the little time there is with my son

The professional who was supposed to write a medical certificate, said to me when he was told that I was the only one not having mental health problems (yet) of everyone in our family: "oh… and you don’t have any symptoms?" then he looked at me like it was just as well to admit me (to the hospital), too!

Keeping family experiences private

This category captures how relatives’ attempts at openness, when met with stigmatizing attitudes, resulted in a decision to keep things private. This included not only actual stigma but also fear of stigma. The fact that their openness and explanations often were met with prejudice, ignorance and/or a feeling of people even not wanting to understand, reinforced the participants’ perception that they should keep quiet.

One way of avoiding prejudice and stigma, was to choose activities and environments only according to what their next of kin was up to without drawing negative attention. They carefully chose social circles in order not to have to explain and/or defend why they associated with and supported their affected family member. In particular, this was the case when the ill offspring still shared the household with the parent(s). Several relatives described how they would avoid going to restaurants, large gatherings or taking trips since this would make them unable to relax when people stared and whispered. Someone described the social limitation as "not hanging out with people who don’t treat the (adult) children with respect.” Relatives thus protected themselves against other people’s prejudices and incorrect images of what mental illness is about by limiting their social contacts and arenas. A participant described why the family chose to keep the situation private:

We have tried to be honest with others about our adult son’s illness, but now we have stopped telling because we can’t stand all the stupid comments and advice. We pretend that everything is ok, to avoid having to carry this extra burden.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate, in a Swedish context, how relatives with a next of kin treated for SMI experience family stigma and how they strive to handle stigmatization. The four categories shown in the result section implicitly describe that these areas are interwoven and thus add to the experience of being trapped in the experience of family stigma, despite attempts to handle the situation: for their own part, they needed to openly share their experiences and concerns about their mentally ill next of kin and their own situation, with family, friends, and colleagues- with a hope of receiving understanding and acknowledgement. However, repeated experiences had proven that doing so could worsen the situation. This is in line with the results that appeared in the qualitative reviews by Yin et al. (Yin et al., Citation2020) and Manesh et al. (Manesh et al., Citation2023), who found that stigmatization was related to the negative attitudes of society and the social network, which lead to psychological consequences, and shortcomings in psychiatric care where relatives experienced negative attitudes from healthcare professionals. This indicates that these aspects are of international interest to minimize the incidence of stigmatization of relatives of people with mental illness. In the review by Manesh et al. (Manesh et al., Citation2023), additional aspects that were not identified in the present study also emerged, such as that stigma can be related to cultural norms, to social structure, and to laws. These aspects may be relevant in Sweden, although not being found in the present study. The fact that relatives initially try to share their experiences and knowledge with others, but in many cases end up keeping it a secret and choosing social isolating is also pointed out by Yin et al. (Yin et al., Citation2020) and Manesh et al. (Manesh et al., Citation2023). In line with this, Karnieli-Miller et al. (Karnieli-Miller et al., Citation2013) found that hurt, disappointment and shame could stem from family member’s experiences of blame, rejection and avoidance from other people. This sheds extra light to our finding that relatives may find it necessary to choose social isolation in order to avoid such negative experiences. In the present study, we found that despite the relatives’ desire for openness about mental illness in the family, they felt compelled to keep this secret in order to avoid stigma from those around them.

Our results show that the relatives often would avoid situations where stigma might be elicited, which aligns with the quantitative findings of Allerby et al. (Allerby et al., Citation2015). This should be a warning signal, as social support is an important source of support for relatives (Thara et al., Citation1998). However, our result also showed examples of strengthened family ties and a willingness on the part of relatives to speak up and fight against prejudices, which should be noted as an important resource that should be supported by healthcare personnel.

In the larger study from which the sample for the current study was drawn, almost three quarters of the participants reported that they did share their situation with relatives and friends (Sjöström et al., Citation2021). Our study expands on these results, by elucidating possible costs of such openness.

The present study’s participants described that their meetings with mental healthcare professionals were characterized by a lack of acknowledgement of their own situation. This is in line with results described in both quantitative (Ewertzon et al., Citation2011), qualitative (Ewertzon et al., Citation2012; Martinsen et al., Citation2020), and mixed methods (Maybery et al., Citation2021) studies, which taken together highlight relatives’ feelings of alienation from the patient´s treatment and decision-making processes. Being met with a lack of understanding and even offensive statements and accusations while in a vulnerable situation meant they would meet mental healthcare professionals with a hope of being recognized and understood. The participants’ descriptions regarding this can be seen as an experience of having a lost opportunity to be met based on one’s own needs. These needs revolve around being able to be completely open, both about the mentally ill next of kin’s and their own situation, and to be acknowledged and listened to regarding the knowledge they possess.

The rejections experienced lead to relatives "giving up" and that they ultimately chose to keep their family’s experiences private - both to avoid offense for themselves, and to protect their mentally ill family member. Family stigma has been shown to negatively affect relatives’ quality of life and burden (Allerby et al., Citation2015; Sjöström et al., Citation2021; H. Stuart et al., Citation2008; van der Sanden et al., Citation2016) and negative experiences with family relations, social contacts, and self-esteem (Heather Stuart et al., Citation2008; H. Stuart et al., Citation2008). Our findings are also in line with Graneheim & Åström (Graneheim & Åström, Citation2016), that in addition to becoming socially isolated and lonely, these relatives kept their situation a family secret, and had difficulties in sharing their experiences with friends out of fear of being judged (Clarke & Winsor, Citation2010). This should be understood by the fact that familial and social support can act as buffers against stressful life situations (Dollete et al., Citation2004; Magliano et al., Citation2002; Mohammed & Ghaith, Citation2018; Raj et al., Citation2016; Ruud et al., Citation2015).

Our findings show that relatives’ handling of family stigma, is complex and somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, the relatives want openness because doing so can reduce stigma, but on the other hand, openness can lead to violation and alienation, which is almost impossible for relatives to overcome on their own. The role of mental health professionals in decreasing the impact of family stigma is thus central.

As early as in 2008, Larson and Corrigan (Larson & Corrigan, Citation2008) described ways to incorporate strategies into treatment plans for family members to deal with stigma. These included increased awareness of stigma, participation in anti-stigma programs, learning coping techniques, and being provided with opportunities to practice coping. Despite this long-standing awareness of family stigma on the part of researchers, and their valuable suggestions of what might be done about it, our results clearly show that there remains a substantial need for measures that can break the vicious circle of family stigma and isolation. Mental health professionals can alleviate this by acknowledging relatives’ experiences and providing them with information and support. Care models such as ACT (Weimand et al., Citation2018) and RACT (Sjöström et al., Citation2021) as well as EASE (Foster et al., Citation2019) and the Family Model (Falkov et al., Citation2020) may facilitate involvement of relatives. For example, participants in the two former studies experienced a positive approach from the healthcare professionals to a large extent; relatively few felt alienated from their next of kin’s mental health care. This indicates that the attitudes of care professionals, as well as the models employed in care delivery have an impact also on how relatives are being met. Beyond the health care sphere, peer groups can be helpful, as described by the participants in our study and in other settings by Yin et al. (Yin et al., Citation2020).

To break the vicious circle of family stigma related to SMI, measures are needed both for relatives and for health care professionals: relatives need acknowledgement, awareness, knowledge and support in order to handle family stigma. This means that health care professionals need increased and specific expertise about family stigma, in order to be able to give relatives the necessary support. It is also a question of attitude, moving away from patriarchal care, toward care that values shared decision-making with involvement of both patients and their families. Implementation studies on models with a family focus, and studies measuring the effect of various measures to prevent family stigma related to SMI should be performed.

Methodological considerations and limitations

To ensure trustworthiness, we based our analysis on Guba’s four criteria: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Guba, Citation1981). The use of open-ended questions supported credibility, since this gave the participants the opportunity to freely express their opinions. The interviewers were familiar with the research field and had a preunderstanding of the situation of next of kin of persons with SMI. To avoid biases and to ensure credibility of the theme and underlying categories, all authors participated in the analysis and sought to challenge their preunderstandings. Furthermore, we continuously discussed our understanding, went back to the transcripts to ensure we were able to grasp the participants’ meaning, and included nuances or deviant statements to cover all aspects of the content. Unfortunately, we were not able to perform member checking, which could have increased trustworthiness by confirmation of our findings. By openly describing the process from recruitment to data collection, participants, and analysis process, we sought to ensure transferability. The study was performed in Western Sweden, and caution should be made regarding transferability of the results. It is however a strength that as many as 65 participants from 16 different mental healthcare units, gave written free-text responses to the same open question about family stigma, which confirmed dependability. However, the material stemmed from a written questionnaire, which meant that the researchers had no opportunity to pose follow-up questions. Finally, we sought confirmability by supporting the content of each category with quotations from the participants and discussing our results considering other relevant studies.

Conclusion

Our study is in line with previous research that has shown that relatives do experience family stigma. Additionally, our study clearly shows that also mental healthcare personnel may add to relatives’ experience of family stigma. Mental healthcare personnel must change their practices so that they do not become an actual additional burden for relatives. Instead, they must update their competences and skills and include measures of support for these relatives. By meeting them openly, relatives’ hope for understanding and support may be realized, and the vicious circle of hope and despair can be broken.

Authors’ contributions

All listed authors are entitled to authorship, meet the criteria for authorship and have approved the final article.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Research Committee in Gothenburg, No. T112-18, ad 151-17.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants who willingly shared their experiences.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allerby, K., Sameby, B., Brain, C., Joas, E., Quinlan, P., Sjöström, N., Burns, T., & Waern, M. (2015). Stigma and burden among relatives of persons with schizophrenia: Results from the Swedish COAST study. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(10), 1020–1026. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400405

- Bos, A. E., Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2013). Stigma: Advances in theory and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746147

- Clarke, D., & Winsor, J. (2010). Perceptions and needs of parents during a young adult’s first psychiatric hospitalization:“We’re all on this little island and we’re going to drown real soon”. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(4), 242–247. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903383992

- Crapanzano, K. A., Deweese, S., Pham, D., Le, T., & Hammarlund, R. (2023). The role of bias in clinical decision-making of people with serious mental illness and medical co-morbidities: A scoping review. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 50(2), 236–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-022-09829-w

- Dollete, M., Steese, S., Phillips, W., & Matthews, G. (2004). Understanding girls’ circle as an intervention on perceived social support, body image, self-efficacy, locus of control and self-esteem. The Journal of Psychology, 90(2), 204–215.

- Ebrahim, O. S., Al-Attar, G. S., Gabra, R. H., & Osman, D. M. (2020). Stigma and burden of mental illness and their correlates among family caregivers of mentally ill patients. Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association, 95(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-020-00059-6

- Ewertzon, M., Andershed, B., Svensson, E., & Lützén, K. (2011). Family member’s expectation of the psychiatric healthcare professionals’ approach towards them. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 18(2), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01647.x

- Ewertzon, M., Cronqvist, A., Lützén, K., & Andershed, B. (2012). A lonely life journey bordered with struggle: Being a sibling of an individual with psychosis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.633735

- Ewertzon, M., Lützén, K., Svensson, E., & Andershed, B. (2010). Family members’ involvement in psychiatric care: Experiences of the healthcare professionals’ approach and feeling of alienation. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(5), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01539.x

- Falkov, A., Grant, A., Hoadley, B., Donaghy, M., & Weimand, B. (2020). The family model: A brief intervention for clinicians in adult mental health services working with parents experiencing mental health problems [Vitenskapelig artikkel]. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54(5), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420913614

- Foster, K., Goodyear, M., Grant, A., Weimand, B., & Nicholson, J. (2019). Family‐focused practice with EASE: A practice framework for strengthening recovery when mental health consumers are parents. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12535

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled information. Harmondswor Penguin.

- Graneheim, U., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Graneheim, U. H., & Åström, S. (2016). Until death do us part: Adult relatives’ experiences of everyday life close to persons with mental ill-health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(8), 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1192707

- Guba, E. G. (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ, 29(2), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766777

- Johansson, A., Anderzén-Carlsson, A., & Ewertzon, M. (2019). Parents of adult children with long-term mental disorder: Their experiences of the mental health professionals’ approach and feelings of alienation–A cross sectional study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(6), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.10.002

- Johansson, A., Ewertzon, M., Andershed, B., Anderzen-Carlsson, A., Nasic, S., & Ahlin, A. (2015). Health-related quality of life—From the perspective of mothers and fathers of adult children suffering from long-term mental disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.02.002

- Johnstone, M. J. (2001). Stigma, social justice and the rights of the mentally ill: Challenging the status quo. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 10(4), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2001.00212.x

- Karnieli-Miller, O., Perlick, D. A., Nelson, A., Mattias, K., Corrigan, P., & Roe, D. (2013). Family members’ of persons living with a serious mental illness: Experiences and efforts to cope with stigma. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 22(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2013.779368

- Larson, J. E., & Corrigan, P. (2008). The stigma of families with mental illness. Academic Psychiatry: The Journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry, 32(2), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.87

- Magliano, L., Marasco, C., Fiorillo, A., Malangone, C., Guarneri, M., & Maj, M. (2002). The impact of professional and social network support on the burden of families of patients with schizophrenia in Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(4), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02223.x

- Manesh, A. E., Dalvandi, A., & Zoladl, M. (2023). The experience of stigma in family caregivers of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A meta-synthesis study. Heliyon, 9(3), e14333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14333

- Martinsen, E. H., Weimand, B., & Norvoll, R. (2020). Does coercion matter? Supporting young next-of-kin in mental health care. Nursing Ethics, 27(5), 1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019871681

- Mascayano, F., Tapia, T., Schilling, S., Alvarado, R., Tapia, E., Lips, W., & Yang, L. H. (2016). Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean: A systematic review. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999), 38(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1652

- Maybery, D., Jaffe, I. C., Cuff, R., Duncan, Z., Grant, A., Kennelly, M., Ruud, T., Skogoy, B. E., Weimand, B., & Reupert, A. (2021). Mental health service engagement with family and carers: What practices are fundamental? BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1073. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07104-w

- Mohammed, S. F. M., & Ghaith, R. F. A. H. (2018). Relationship between burden, psychological well-being, and social support among caregivers of mentally ill patients. Egyptian Nursing Journal, 15(3), 268.

- Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: A systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 40(5), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0430-z

- Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., & Monroe, A. E. (2012). The infection of bad company: Stigma by association. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026270

- Raj, E. A., Shiri, S., & Jangam, K. V. (2016). Subjective burden, psychological distress, and perceived social support among caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 32(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-9962.176767

- Reupert, A., Gladstone, B., Helena Hine, R., Yates, S., McGaw, V., Charles, G., Drost, L., & Foster, K. (2021). Stigma in relation to families living with parental mental illness: An integrative review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12820

- Ruud, T., Birkeland, B., Faugli, A., Hagen, K., Hellman, A., Hilsen, M., & Weimand, B. (2015). Barn som pårørende-Resultater fra en multisenterstudie (Children as next of kin-Results from a multicenter study). IS-05022. Akershus universitetssykehus HF.

- Shi, Y., Shao, Y., Li, H., Wang, S., Ying, J., Zhang, M., Li, Y., Xing, Z., & Sun, J. (2019). Correlates of affiliate stigma among family caregivers of people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26(1-2), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12505

- Sjöström, N., Waern, M., Johansson, A., Weimand, B., Johansson, O., & Ewertzon, M. (2021). Relatives’ experiences of mental health care, family burden and family stigma: Does participation in patient-appointed resource group assertive community treatment (RACT) make a difference? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 42(11), 1010–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2021.1924322

- Stuart, H., Koller, M., & Milev, R. (2008). Appendix inventories to measure the scope and impact of stigma experiences from the perspective of those who are stigmatized–Consumer and family versions. Understanding the stigma of mental illness: Theory and interventions., 193–204.

- Stuart, H., Koller, M., Milev, R., Arboleda-Florez, J., & Sartorius, N. (2008). Understanding the stigma of mental illness: Theory and interventions.

- Thara, R., Padmavati, R., Kumar, S., & Srinivasan, L. (1998). Instrument to assess burden on caregivers of chronic mentally ill. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 40(1), 21.

- van der Sanden, R. L., Pryor, J. B., Stutterheim, S. E., Kok, G., & Bos, A. E. (2016). Stigma by association and family burden among family members of people with mental illness: The mediating role of coping. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(9), 1233–1245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1256-x

- van der Sanden, R. L., Stutterheim, S. E., Pryor, J. B., Kok, G., & Bos, A. E. (2014). Coping with stigma by association and family burden among family members of people with mental illness. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(10), 710–717. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000189

- Weimand, B., Israel, P., & Ewertzon, M. (2018). Families in assertive community treatment (ACT) teams in Norway: A cross-sectional study on relatives’ experiences of involvement and alienation. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(5), 686–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0207-7

- Weimand, B. M. (2012). Experiences and nursing support of relatives of persons with severe mental illness.

- Yin, M., Li, Z., & Zhou, C. (2020). Experience of stigma among family members of people with severe mental illness: A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 141–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12668

- Zhang, Z., Sun, K., Jatchavala, C., Koh, J., Chia, Y., Bose, J., Li, Z., Tan, W., Wang, S., Chu, W., Wang, J., Tran, B., & Ho, R. (2020). Overview of stigma against psychiatric illnesses and advancements of anti-stigma activities in six Asian societies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(1), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010280