Abstract

Communication in healthcare extends beyond patient care, impacting the work environment and job satisfaction. Interprofessional communication is essential for fostering collaboration, but challenges arise from differences in training, roles, and hierarchies. The study aimed to explore psychiatric outpatient clinicians’ experiences of interprofessional communication and their perceptions of how the communication intersects the organizational and social work environment of healthcare. Qualitative research involved focus group interviews with clinicians from five psychiatric outpatient units in Central Sweden, representing diverse professions. The authors analyzed semi-structured interview data thematically to uncover clinicians’ perspectives on interprofessional communication. An overarching theme, “Adjustment of communication,” with subthemes “Synchronized communication” and “Dislocated communication,” emerged. Clinicians adapted communication strategies based on situations and needs, with synchronized communication promoting collaboration and dislocated communication hindering it. Communicating with each other was highly valued, as it contributed to a positive work environment. The study underscores the importance of an open, supportive environment that fosters trust, and respect among healthcare clinicians. Consistent with prior research, collaboration gaps underscore the urgent need to improve interprofessional communication.

Introduction

The exploration of effective communication within the healthcare sector is a well-established area of research (Barnard et al., Citation2020; Bok et al., Citation2020; Foronda et al., Citation2016). Interprofessional communication is the linchpin of successful collaboration among diverse healthcare team members. The transfer of information through verbal and nonverbal channels, coupled with the dynamic interplay of contextual elements, such as the physical environment (Paxino et al., Citation2022), constitutes the intricate landscape of healthcare communication. Healthcare professionals endeavor to foster a culture of caring within interprofessional teams, promoting shared understanding and facilitating effective communication across diverse roles and specialities (Wei et al., Citation2020). Given the multifaceted nature of patient needs, collaboration among healthcare providers becomes indispensable across all healthcare settings. The healthcare literature defines interprofessional collaboration as an active and continuous partnership that brings together professionals from varying backgrounds, each characterized by unique professional cultures (Morgan et al., Citation2015).

Undoubtedly, communication plays a pivotal role in ensuring patient safety and optimizing healthcare outcomes (Daheshi et al., Citation2023; Umberfield et al., Citation2019), contributing not only to patient care but also to a positive work environment and job satisfaction (Boev et al., Citation2022; Ma et al., Citation2018). Within this framework, effective teamwork, marked by continuous feedback and shared role and goal comprehension among all team members, is crucial for positive patient outcomes (Boev et al., Citation2022). However, variations in education, training, roles, and hierarchies across healthcare professions present significant obstacles to effective communication (Nguyen et al., Citation2019; Paxino et al., Citation2022). The dominant position of physicians within the healthcare hierarchy can impede the integration of nurses and other professionals as well as how they are understood, leading to conflicts (Etherington et al., Citation2019; Foronda et al., Citation2016; Gleeson et al., Citation2023; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Despite progress in understanding communication dynamics, organizational initiatives that promote trust, respect, and collaboration remain relatively unexplored.

Extensive research indicates that improved work environments are linked to reduced odds of adverse outcomes for both patients and clinicians, from patient mortality to job dissatisfaction (Lake et al., Citation2019). In this context, the nursing environment, as defined by Lake (Citation2002), pertains to the organizational characteristics within a work environment that either facilitate or hinder professional nursing practice. Professional practice environments, as described by Friese et al. (Citation2008), play a critical role in enabling clinicians to operate at the highest level of clinical practice, fostering effective collaboration within multidisciplinary teams and expeditious resource mobilization, ultimately enhancing the quality of care. A link has been established between the professional practice environment and various nursing outcomes, including unmet patient care needs, job satisfaction, burnout, intent to leave, and missed nursing care (Zeleníková et al., Citation2020). These findings underscore the vital relationship between the work environment, the practice environment, and the overall well-being of clinicians and their patients, providing valuable insights for clinicians and policymakers alike.

To address this research gap, the present study will explore psychiatric outpatient clinicians’ experiences of interprofessional communication and their perceptions of its intersections with the organizational and social working environment (AFS2015:4, Citation2016). The study will contribute to an improved and deeper understanding of interprofessional communication in line with the principles of modern healthcare workplaces and their holistic approach to employee well-being.

Aim

The present study aimed to explore psychiatric outpatient clinicians’ experiences of interprofessional communication and their perceptions of how the communication intersects the organizational and social work environment of healthcare.

Methods

Design

A qualitative research approach with an explorative design using focus group interviews was chosen. We conducted a thematic analysis of the collected empirical material. A qualitative approach was considered suitable for exploring human experiences and interpreting written text from interviews.

Setting and participants

A purposive sample of multi-professional clinicians from five psychiatric outpatient units in central Sweden was established. Selection of the psychiatric outpatient units was based on expediency and geography. The inclusion criterion stipulated that the outpatient unit should involve diverse clinicians thus, clinicians participating in the focus group held varying occupational roles. Information on professional titles and how long the clinicians had worked at the current workplace was requested; the duration of employment at the current outpatient unit ranged from 5 wk to 19 years, with the average length and median being around 5.5 years. depicts the diversity of clinician participants by number and profession.

Initial contact with unit managers at the selected psychiatric outpatient unit was made via email by the first author, inquiring about interest in participating in the focus group. Afterward, written information was sent to all clinicians at the unit. The first author then sent a follow-up via e-mail within a few weeks to confirm interest in participating and to set a date for the focus group. Before the focus group began, the clinicians received verbal information and signed the consent form.

Data collection

For the present study, we conducted five semi-structured focus groups each comprising 2-4 clinicians working in psychiatric outpatient units. A focus group is an informal gathering in which chosen participants collectively discuss topics presented as a set of researcher-selected questions (Rabiee, Citation2004). These participants can be preexisting groups or individuals specifically assembled for research, with an emphasis on homogeneity in factors such as occupation and age. This approach encourages a natural and interactive conversation (Wilkinson, Citation1998). Following Wilkinson’s approach (1998), we employed focus groups as a methodology to investigate research questions from the clinicians’ perspectives, thus gathering their insights, views, and opinions. This approach enabled an in-depth exploration of individual perspectives through group interactions, resulting in valuable data (Morgan & Bottorff, Citation2010).

In conducting our focus groups, we used a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) developed collaboratively with all authors. It featured leading and follow-up questions to elicit comprehensive participant responses, covering communication characteristics and perceptions within professional groups based on previous research. The authors pre-arranged the question sequence before the focus groups to maximize discussion opportunities and uphold consistency. In addition, the dynamics of collaboration were also discussed, and the clinicians were able to share their experiences of how collaboration between different professional groups was experienced. Data collection was conducted between February and June 2023. The interviews lasted approximately 60–70 min (mean 66 min) each and were held at the various units in conference rooms or in a clinician’s room.

Before the focus groups, the researchers were aware of the influence of group dynamics. Author 1, with support from either Author 2 or 4, demonstrated readiness and implemented a strategic plan to conduct the focus groups. This strategy included confirming and following up on responses and facilitating equal opportunities for all group members to contribute. Various notes were taken during the sessions, with details such as the progression of the interview questions and non-verbal reactions. However, these notes were not considered to contribute to the material analysis.

In the current study, Author 1, leveraging prior research experience in qualitative interviews, assumed the role of the main moderator. The data were recorded via audio recording files, and in the context of focus groups, either Authors 2 and 4, leveraging significant expertise in various research methods, including focus groups, assumed the role of assistants to keep track of time and ask additional questions. In one case, the first author led the group alone; this group included clinicians from a professional category not represented at previous sessions.

Data analysis

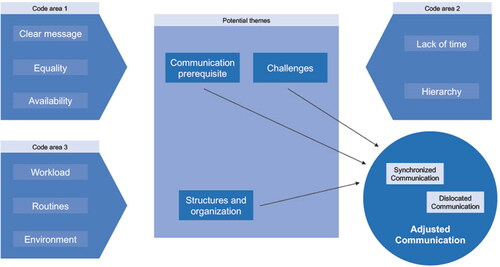

The present data analysis followed the thematic analysis approach proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Thematic analysis is valuable when the researcher wants a relatively straightforward approach to interpreting qualitative data (Vaismoradi et al., Citation2013). The first author initially transcribed the audio recordings verbatim, and then carefully removed all identifying information to ensure complete anonymity. Subsequently, the first author read the transcribed data in-depth to become thoroughly acquainted with the transcript’s content. During this process, specific text segments related to the study’s objectives were methodically identified and coded for further analysis, see examples in .

Following this familiarization process, the codes were systematically grouped into potential themes, with all pertinent data organized accordingly. This step aimed to discern overarching patterns within the dataset; see examples in . In thematic analysis, the significance of a theme does not necessarily rely on quantifiable metrics but rather on whether it captures something substantial about the overarching research question (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Following this, Author 1 and Author 4 reviewed the themes to ensure they were in accordance with the previously coded extracts and the dataset as a whole. As part of the process, Author 1 found that the theme contained sub-themes. Subthemes essentially function as themes within a broader thematic category; they structure and clarify complex themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2023). In the next step, Author 1, in consultation with Author 4, assigned clear and descriptive names to each theme. Finally, in line with Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2023) methodology, all authors engaged in discussion and carefully chose vivid and compelling excerpts that served as illustrative examples of each subtheme and overarching theme.

Code area 1: A clear message is a prerequisite for good communication, as it increases the probability of getting an answer to what was requested. Equality is a prerequisite for good interprofessional communication and it helps individuals to dare to ask questions and consult despite differences in the professions. Accessibility, proximity, and open doors invite both formal and informal conversations and discussions between the professions.

Code area 2: Lack of time sometimes leads to communication being shorter and worse or not happening at all. Hierarchy can create challenges in team situations when individuals do not dare to express themselves or to ask questions based on hierarchical situations.

Code area 3: Depending on the workload (e.g., many patients), communication can be promoted or hindered. Local guidelines and routines regarding unit work, team conferences, and collaboration impact communication. The work environment significantly influences both work and communication, manifesting in interprofessional interactions.

Rigor

Reflexivity

The first author, a Ph.D. student and registered nurse specializing in psychiatric nursing and education, addressed personal biases and preconceptions throughout the study and incorporated these considerations into analyses and discussions with coauthors. During data collection, deliberate efforts were made to allow participants ample opportunity to express their experiences.

Trustworthiness

Ensuring credibility, transferability, trustworthiness, confirmability, verifiability, and reflexivity (Nowell et al., Citation2017) guaranteed the research’s reliability. Detailed record-keeping for recordings, transcripts, and coding, along with clear documentation of decisions, increased the study’s reliability and auditability.

To address transferability and authenticity (Connelly, Citation2016), quotes from the focus groups can be found. Although qualitative research cannot be fully transferred, the results can resonate with the readers’ experiences, given the extensive presentation of the participants’ statements in the form of quotes.

The use of an interview guide for consistent questioning across focus groups enhances study credibility. Accurate reporting, well-documented decisions, and auditability were ensured in this study, reinforcing its trustworthiness.

Ethical considerations

The present study received ethical approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Approval no. 2022-00023-01). All participants were given written and verbal information to ensure their understanding of the study’s objectives and the researcher’s role, as outlined by Draper (Citation2015). Moreover, the clinicians were informed of the professional backgrounds of the moderator and assistant, their underlying reasons for exploring the subject matter, and the explicit intention to analyze and subsequently publish the focus group data in a reputable scientific journal. The participant information encompassed aspects such as the voluntary nature of participation, the option to withdraw at any point without the need to provide a reason, and the guarantee that confidentiality would be strictly maintained. All participating clinicians gave their informed consent. Only members of the research team had access to the original audio files and transcripts. Given the limited size of each professional group, consisting of only a few clinicians, and to safeguard confidentiality, the quotes presented in the results section are not attributed to specific individuals.

Results

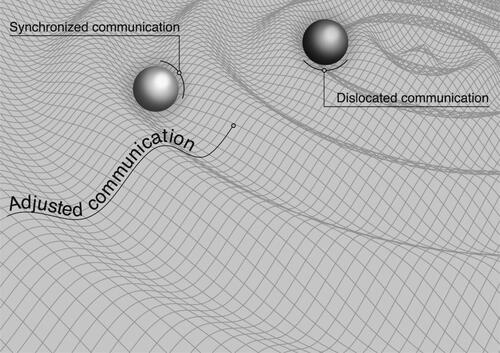

One overarching theme was found, “Adjusted Communication,” containing two subthemes: “Synchronized Communication” and “Dislocated Communication”; see .

Our results showed how clinicians in psychiatric outpatient units experienced interprofessional communication and how it intersected with their work environment. The theme “Adjusted Communication” served as the basis of all communication, elucidating how clinicians in open psychiatric units adjusted their communication strategies to optimize outcomes. This adjustability was essential to understanding the dynamics of communication within this specific context.

We clarify the complex theme of "Adjusted communication" by presenting two subthemes: "Synchronized Communication" and "Dislocated Communication," where each subtheme entails adjustment to achieve good interprofessional communication. Synchronized Communication focuses on situations when communication flows smoothly and efficiently, while Dislocated Communication focuses on situations when communication is broken, unclear, or ineffective due to various elements and obstacles. The results offer a detailed understanding of how clinicians in psychiatric outpatient units adjusted their communication approaches.

Adjusted communication

The clinicians reported that they adjusted their communication strategies to address distinct situations, contextual nuances, and individual requirements. Within the realm of interprofessional communication, it became conspicuously clear that adjustability served as the bedrock for fostering efficacious interpersonal and interprofessional exchanges.

To explore interprofessional communication in psychiatric outpatient care, it was important to consider the perspective shared by psychiatric outpatient clinicians, as well as the importance of clear and effective communication. One nurse in a focus group expressed this very aptly: “It’s an art to communicate so that you understand each other.” The clinicians said that good communication is a key element in creating successful care teams and improving the quality of care.

However, to enable good communication, several important elements were identified. Formulating the message is the initial step, followed by obtaining feedback to confirm understanding. Various communication methods were used, including conversations, team meetings, and conferences, as well as digital platforms such as journal entries.

They described adjusting their communication depending on the recipient. Taking a closer look, a particularly notable aspect was the necessity to consolidate and refine onés messages, especially in communication with physicians. Communication with physicians tended to be more structured and focused. In these interactions, the other clinicians tried to be as clear as possible and avoid unnecessary details, such as extensive background information or non-essential medical history, the goal being to save time and streamline the dialogue as one clinician put it:

If you want to communicate with a physician, you have to be sure of what you want to bring up, the purpose, how should I express this… if I want to bring up this time now with this physician, then I really have to know what I want or maybe you write a report instead of running into the physician’s room.

Because otherwise, it doesn’t flow for me, it’s not a burden but it’s rather that I just sweep a little in front of me and the patient… If I prompt the psychiatrist to check a brief note, it prevents misunderstandings, avoiding the patient coming back to me for clarification over multiple calls and weeks ahead.

In line with the study’s aim, it was worth noting evident inconsistencies in communication styles observed across distinct professional groups. Of particular significance was that the physicians emerged as a group exhibiting a communication style that deviated from the norm. Other clinicians suggested that this deviation could be attributed to their unique educational background and professional culture. As a physicians put it:

"The physician’s role, encompassing medical management and navigating hierarchies, results in communication gaps and hidden agendas. The risk of being perceived as authoritarian poses challenges. Anecdotes about junior doctors facing strong hierarchies, with senior doctors wielding almost papal authority, underscore the need for a fair working environment." This is corroborated by a psychologist who notes: "There’s a saying not to knock on physicians’ doors; you can get scolded. In our guidelines, it says to avoid disturbing physicians with corridor matters and the like."

In contrast, the other professional groups were more inclined to explore alternative perspectives and approaches. Other clinicians preferred a culture that promoted mutual collaboration and dialogue with different professional categories and emphasized solutions.

Synchronized communication

Synchronized communication alluded to a communication approach characterized by coordination and optimal efficiency, ensuring that all clinicians were in alignment with one another. This mode of communication promoted mutual comprehension among team members, emphasizing its crucial significance within professional domains where precise and coordinated interactions were vital to attaining favorable results.

Clinicians consistently emphasized the value of opportunities for communication with their colleagues. Such interactions were highly regarded as they not only contributed to a pleasant working environment but also played a central role in enhancing the overall effectiveness of the care delivery process. Work community was expressed as a central and significant aspect of interprofessional communication. The clinicians expressed being acknowledged, which created a sense of mutual trust and openness to asking questions, sharing insights, and offering support.

Within this work culture, clinicians found an environment that promoted open and welcoming interaction, with open doors facilitating conversation and dialogue. They actively participated in synchronized discussions and engaged in informal communication with their colleagues, preferring a less formal structured dialogue over formal structures like SBARS (Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation). Notably, synchronized communication within the same professional category tended to be more detailed and descriptive. As one nurse put it:

We nurses socialize differently, in other contexts and meet each other much more, it’s, therefore, easier to just run in and say something… nurses can communicate with each other more with words, and then you have the same basic understanding in the same professional categories, that you have somewhat the same game plan so that you have the same mindset.

Another important element of promoting effective communication involved emphasizing the sense of community and shared responsibility for patient-centered care and reinforcing the fact that no one was alone and that working around the patient was a collective task: “We help each other around the patient and share with each other, so it’s not yours or mine, it’s our patient.” In this context, everyonés communication was considered equally important, and the clinicians considered each other as equals, all with the patient’s best interests in focus. This emphasized the need for synchronized and effective communication across professional boundaries and enabled a holistic view of patients’ problems and care planning.

Physical proximity in the workplace was also expressed to contribute to effective and open communication. When clinicians shared the same floor and there was an open-door culture, the environment was more inviting for spontaneous conversations and discussions. On the other hand, those who did not have the same physical proximity or experienced that the doors were often closed, described a challenge in seeking out their colleagues for communication: “It’s not possible to run around looking for people.”

Communicating with colleagues was highly valued, as it contributed to a pleasant work environment and freedom under responsibility, creating a positive work environment where employees expressed independency and responsibility.

Dislocated communication

The features of dislocated communication were broken, unclear, or ineffective communication, and a situation in which some chose not to express themselves due to various elements and obstacles such as lack of time, physical distance, reprimands, and fear of being questioned, which affected cooperation between healthcare clinicians within open psychiatric care.

There was consensus regarding a significant lack of communication, and a lack of mutual understanding between different care activities emerged. One rehab coordinator conveyed their thoughts as follows: “It’s a frustration in my professional role to see how patients are, quite frankly, bowled over because of territorial thinking, hierarchically thinking, so it’s a difference between primary care and specialist care.” This was a shared opinion among clinicians from diverse professional backgrounds who had dealt with similar experiences. The clinicians emphasized the obstacles that arose in the collaboration between specialist psychiatry and primary care or inpatient care. A nursing assistant pointed out: “Communication between, after all, it is the same actor, no, it doesn’t work, it’s not good. There isn’t really an understanding of what the other is doing….”

Although most participating clinicians expressed that hierarchy was less evident in psychiatric care, there was still an experience of power and dominance techniques, particularly related to professional roles and professions. Regarding dislocated communication, certain clinicians related their perception that their expertise and years of experience were sometimes undervalued, particularly in their interactions with primary care physicians.

There is a lot of collaboration between primary care and rehab coordinators and in collaboration meetings where physicians from primary care are involved, you get flattened…me in my professional role without the clinical part… there it’s a completely different, completely different treatment, you aren’t at all interested in what I know and can do.

However, this lack of understanding of other clinicians’ professional roles was not only observed among the physicians. One occupational therapist also expressed the following: “Generally, we may not have the best knowledge of each other’s work areas and then it may not be the best communication or understanding, and that makes cooperation difficult.”

The problem also extended to difficulties and dislocated communication from ward physicians to outpatient clinicians, where a lack of understanding of each other’s work areas and roles prevented effective collaboration. One clinician put it in this way: “Cooperation between inpatient and primary care generally doesn’t work very well. We miss each other in this completely absurd way, where we just glide by each other on the most obvious things where we should be collaborating.”

Furthermore, the clinicians reported that communication between physicians was also deficient and was sometimes completely absent. It was common for physicians not to communicate with each other, even if inpatient and outpatient care were in the same building, only one floor apart. As one clinician emphasized: “Communication between physicians, is extremely lacking, extremely, yes, it’s zero. Usually, they don’t talk to each other, especially between floors.”

Some clinicians noted a connection between power dynamics and education levels, where higher-educated individuals received more respect, notably in treatment conferences. When clinicians perceived that their voices went unnoticed or disrespected, they often disengaged from discussions and opted to share their perspectives with interested parties post-conference. Some clinicians emphasized that ignorance was sometimes an issue that affected experiences of hierarchy and dislocated communication.

Sometimes I can be taken seriously, sometimes not, in terms of education I don’t know, but in terms of experience, I feel that maybe people don’t trust me, it probably goes back to this issue of ignorance, I believe, regarding what I do and the knowledge I possess…. in terms of experience that you don’t always take what I say into account, then I back off, I do.

Although, according to the clinicians, open and effective communication was a prominent part of the work culture, a high workload and time pressure negatively affected communication. In high-workload situations, communication may suffer, and clinicians may feel more isolated despite an increased need for collaboration. One clinician said: “The communication might at least be a little shorter… sometimes you don’t have time to communicate what you should,” while another one pointed out that when there was more to do, the need to communicate with others also increased, but lack of time could make it difficult to maintain communication.

Discussion

The present study set out to explore the experiences of psychiatric outpatient clinicians concerning interprofessional communication and its profound intersections with the complex organizational and social work environment. This discussion provides an overview of our exploration of the complex landscape of interprofessional communication within psychiatric outpatient units, paving the way for a more in-depth analysis of its multifaceted aspects and their significant impact on the broader healthcare landscape.

Furthermore, our study does not only explore the intricacies of interprofessional communication, but also aims to uncover how professionalism and power dynamics intertwine with communication, ultimately influencing the work environment and patient care. Communication can be hindered by various elements, including differences in communication approaches and a lack of comprehensive interdisciplinary strategies. Recognizing the value of teamwork among all clinicians involved in patient care is crucial (Boev et al., Citation2022). As mentioned earlier, professional practice environments, characterized by seamless interdisciplinary collaboration, significantly enhance resource mobilization and care quality, ultimately improving patient outcomes (Friese et al., Citation2008). These environments are influenced by factors like relationships and professionals’ positions within the organizational hierarchy (Lake, Citation2002).

Our findings unveiled an overarching theme "adjusted communication,”—that was intricately woven into the fabric of this unique setting. This encompassing concept gave rise to two distinct subthemes: “synchronized communication” and “dislocated communication.” The dynamics of these subthemes were intricately dependent on various elements, including the manner of communication, its content, and timing.

Our research underscores the pivotal role of synchronized communication in fostering a collaborative and harmonious work environment within the realm of healthcare, a point further highlighted and confirmed in a dissertation on synchronous communication by Rochester (Citation2017) who highlights its impact on both in-person and digital interactions. Synchronized communication in professional settings fosters better collaboration through effective communication and focus, leading to reduced errors, enhanced care quality, increased job satisfaction, and retention while promoting real-time interactions and encouraging positive outcomes (Rochester, Citation2017).

In contrast, dislocated communication was identified as a contributing factor to a less favorable work environment, necessitating further adaptations to enhance overall effectiveness.

Within the realm of open psychiatric outpatient units, interprofessional communication can be envisioned as a dynamic spacetime construct. Adjusted communication forms the foundational bedrock of all interactions, while synchronized communication and dislocated communication represent variable elements that generate distinct waves, thus exerting discernible impacts on the organizational and social work environment, as elucidated in .

Furthermore, it is essential to acknowledge pervasive instances of dislocated communication, which create disruptive waves, as supported by our data. This dislocated communication contributes to a workplace culture marked by a reluctance to seek assistance, inhibited self-expression, and potential misunderstandings, all of which may detrimentally impact both the work environment and patient care. In contrast, synchronized communication, generating smoother waves, fosters a collaborative atmosphere characterized by open dialogue, camaraderie, and professional pride. This, in turn, promotes mutual support among clinicians, ultimately enhancing the overall working environment for clinicians.

The figure can be compared to the principles behind the theory of relativity, where time and space are not constant but are affected by different factors. Similarly, the figure illustrates how interprofessional communication within psychiatric outpatient units can be seen as an ever-changing process. Adjusted communication forms the basis of this, like an underlying structure that shapes the work environment. Synchronized and dislocated communication act as dynamic elements that generate waves in the work environment and influence the interaction between professions. This comparison highlights the importance of understanding and navigating different forms of communication to promote an efficient and harmonious work environment.

Prior studies have noted the importance of communication and collaboration between healthcare clinicians (Boev et al., Citation2022; Daheshi et al., Citation2023; Ma et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). In psychiatric care, effective communication is of paramount importance. It ensures patient safety and offers a stronger support system for patients and clinicians (Friedman, Citation2021; Kanerva et al., Citation2015). Research underscores the critical role of communication in psychiatric care, enhancing treatment effectiveness, promoting patient safety, and increasing job satisfaction among interdisciplinary teams (Friedman, Citation2021).

Research on psychiatric inpatient care (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2014) shows that nursing assistants communicated interprofessionally, though mainly with nurses and only sometimes directly with physicians. However, our results showed a different dynamic in outpatient units. In this setting, clinicians had equal opportunities to communicate with each other and clinicians from different professions, but notably, all other clinicians displayed an equally adjusted mode of communication when interacting with physicians.

In the results, one clinician was quoted saying that communication is an art. It is noteworthy that verbal communication and art employ similar mechanisms for constructing significance, emphasizing the common foundation of seeking mutual understanding, which is the essence of meaning-making (Dolese et al., Citation2014). Healthcare communication mirrors art’s nuances, offering profound insights into interprofessional communication intricacies. Similar to art, communication is not just what is said but how, when, and to whom it is said that shapes interpretation (Moudatsou et al., Citation2020). Just like art, interprofessional communication thrives on the interplay of technology, emotion, and context (Vega & Hayes, Citation2019). Interprofessional communication goes beyond transactions, catalyzing transformation and enriching healthcare professionals. This complexity intensifies in interprofessional care, demanding understanding and respect for diverse roles and perspectives. Healthcare professionals employ varied communication strategies, akin to artists using techniques and colors, ultimately mastering this “art” for clinical excellence (Morgan et al., Citation2015; Sun et al., Citation2023).

Noyes’s (Citation2022) research underscores the pivotal role of communication as a fundamental process through which groups create and perpetuate power relationships that significantly influence collaboration. Despite the appearance of stability in hierarchies, they are shaped by routine and, everyday communication, rendering them adaptable to change. A recent study on interprofessional collaboration (Recto et al., Citation2023) emphasizes power differentials in healthcare teams, affecting both team dynamics and communication. The study highlights the importance of cultivating a collaborative and inclusive work environment. For this reason, organizations seeking to enhance collaboration should prioritize addressing power dynamics, alongside other essential considerations such as collaborative skills and processes.

Our study revealed clinicians’ proactive adaptation of communication methods to suit specific contexts and recipients, with a particular emphasis on the importance of feedback solicitation and message clarity. There are several possible explanations for this result. Physicians often adopted an authoritative approach, while other clinicians displayed a greater inclination to consider diverse perspectives (Daheshi et al., Citation2023; Sabone et al., Citation2020; Umberfield et al., Citation2019).

In the realm of psychiatric care, power dynamics and the prevalence of professional hierarchies exert a significant influence on interprofessional communication within the healthcare landscape. Various forms of power, including positional and personal power, yield varying outcomes depending on how they are perceived (Yukl, Citation2008). These power dynamics play a crucial role in interprofessional collaboration, significantly affecting the healthcare environment.

Physicians, despite relying on others for information, maintain decision-making authority due to their formal status, exemplifying what Yukl (Citation2008) refers to as “legitimate power.” These power dynamics can lead to variation in the quality and effectiveness of communication. For instance, physicians, given their distinct roles in the healthcare system, may be perceived as adopting a more authoritative approach (Etherington et al., Citation2019; Gleeson et al., Citation2023).

These hierarchies shape their interactions with other clinicians and their working methodologies. While hierarchies have been extensively studied for their impact on patient safety (Daheshi et al., Citation2023; Gleeson et al., Citation2023; Umberfield et al., Citation2019), it is equally important to recognize their influence on the broader working environment (Karlsson et al., Citation2019).

In our study, we found that the perception that physicians are distinct individuals in the medical field is not solely a consequence of their professional standing; instead, it is a complex issue perpetuated by the beliefs and behaviors of other clinicians. This phenomenon can be viewed as a manifestation of self-stigma within the medical community, where clinicians may have internalized negative stereotypes or biases about their profession and the roles of their peers. As a result, this perceived differentiation helps to reinforce the existing hierarchy within the medical profession.

While efficiency is sometimes cited as a rationale for favoring physicians, even if it results in more work for other team members, challenging power dynamics becomes feasible when interdisciplinary teams prioritize valuing all perspectives and fostering an open and informal environment that encourages free communication (Noyes, Citation2022).

To address this issue and promote a more collaborative practice environment, active engagement from all healthcare professionals, whether they are in medical or non-medical roles, is crucial. This engagement necessitates a process of critical self-reflection and introspection, where individuals recognize and challenge any preconceptions, biases, or stereotypes they may hold about different care roles. Moreover, it requires a commitment to fostering inclusion, open dialogue, and mutual respect among all members of the care team.

Communication, power dynamics, and professionalism collectively underscore the intricate nature of interprofessional communication in psychiatric care and its profound influence on both the quality of patient care and the well-being of clinicians. A nuanced understanding of these elements is paramount to nurturing a supportive and effective healthcare environment.

Professionalism in healthcare involves societal and individual dimensions. Societally, it is a dynamic social contract that considers power dynamics and adaptability. Individually, it comprises self-awareness, effective communication, and ethical decision-making (Aylott et al., Citation2019). This multifaceted understanding of professionalism is crucial in the context of interprofessional communication, as it forms the foundation for effective collaboration and patient-centered care in healthcare settings.

Collaborating within an interprofessional team promotes improvements in patient care, treatment quality, and clinicians’ professional growth and job satisfaction, which also emphasizes how working in interprofessional teams positively contributes to professional development (Anselmann & Disque, Citation2022). Building on our research, we explored interprofessional communication nuances among clinicians, echoing Zheng et al.’s (Citation2017) emphasis on cohesive team interactions and their impact on job satisfaction and patient care. Additionally, our results underscored the significance of clear and concise communication when dealing with physicians, in line with the findings of Vatn and Dahl (Citation2022).

Physical proximity, often an unexpected but vital factor, promotes synchronized communication among care teams. Clinicians in our study acknowledged its role in fostering open discussions, mutual support, and effective patient care. Conversely, spatial barriers, such as having clinicians’ offices on different floors, hinder seamless interaction, restricting informal discussions and the exchange of valuable insights among team members.

Co-locating professionals in a shared workspace fosters increased interaction, elevating the standard of decision-making. Having specialized resources in proximity to one another is essential for positive interprofessional collaboration, as previous research has shown (Bonciani et al., Citation2018; Paxino et al., Citation2022; Rousseau et al., Citation2017; Wener et al., Citation2022).

In the future, healthcare institutions can strategically reconfigure their physical spaces by situating interdisciplinary teams in proximity to one another. At an organizational level, it has been emphasized that teams should be provided with both time and space for intercommunication (Anselmann & Disque, Citation2022). This approach would encourage spontaneous knowledge sharing and facilitate collaborative decision-making within healthcare-focused work environments.

Such architectural modifications could serve as tangible manifestations of an organization’s commitment to fostering interprofessional collaboration, ultimately contributing to potential improvements in clinicians’ satisfaction. Our study highlights the vital need for a supportive work environment that cultivates synchronized communication, trust, and respect among healthcare teams, ultimately improving patient satisfaction (Paxino et al., Citation2022). We also identified a significant deficiency in collaboration and communication among different healthcare entities, in line with the findings of Vähätalo et al. (Citation2022), thus underscoring the complexity of interprofessional communication within psychiatric outpatient units and emphasizing the ongoing need for effective collaboration.

Moreover, the evidence stresses the critical role of a positive practice environment, including nurse-physician relationships (Park et al., Citation2018; Sabone et al., Citation2020; Zeleníková et al., Citation2020). Conversely, poor practice environments are linked to a higher likelihood of missing essential care activities. Enhancing interprofessional interactions and fostering effective communication with physicians emerge as pivotal components in reducing missed care and significantly improving clinicians’ job satisfaction (Manojlovich, Citation2005). These findings underscore the central role of the work environment and interprofessional communication in ensuring high-quality care and clinicians’ job satisfaction, reinforcing the importance of cultivating supportive healthcare environments.

This study on interprofessional communication underscores the nuanced and multifaceted nature of communication in healthcare. The pivotal importance of tailoring messages to specific situations and recipients is evident, serving as a linchpin for optimal outcomes. Likewise, fostering collaborative efforts within a harmonious work environment is essential for successful interprofessional collaboration.

Overcoming communication challenges, adjusting, and emphasizing clear communication with physicians are essential components of this intricate collaborative tapestry. Recognizing the influence of power dynamics, addressing biases, and championing inclusivity contribute to a refined communication continuum, necessitating critical reflection for continuous improvement in professional interactions.

Our study underscores the vital role of cultivating a positive work environment for promoting a healthy working life. Cultivating relationships and fostering effective collaboration within psychiatric outpatient units contribute to a positive atmosphere.

These insights guide the refinement of communication practices in healthcare, setting the stage for ongoing improvement in clinical settings. Exploring interprofessional communication steers us toward increased awareness and improved teamwork in healthcare.

Limitations

Our focus groups, involving a small number of clinicians, may have limited the depth of discussion compared to larger groups. According to Morgan’s recommendations, the ideal number of participants for a focus group is 7–10 (Morgan, Citation1998). For practical reasons, our participants in each focus group came from the same outpatient unit, meaning that homogeneity in factors such as occupation and age (Wilkinson, Citation1998) was not met due to the limited number of participants available. The consequences of having heterogeneous groups are that it provides different perspectives, promotes creativity, and deepens the understanding of the subject. Yet it can also present challenges related to communication and power dynamics. These challenges can mean difficulties in reaching consensus and in turn prevent clear conclusions from being drawn from the focus group (Morgan, Citation1997). Due to scheduling conflicts, no assistant was present during the final session. However, considering the importance of obtaining additional data, we considered it necessary to include this focus group session in our analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study underscores the central role of interprofessional communication in the workplace in ensuring high-quality care and job satisfaction among clinicians, emphasizing the importance of fostering supportive work environments. This research highlights the significance of synchronized communication and physical proximity in psychiatric outpatient units, stressing the complexities of interprofessional communication, and the ongoing need for effective collaboration. The concept of “Adjusted Communication” and the challenges faced by clinicians have broader implications for healthcare. Recognition of the pivotal role played by interprofessional communication in psychiatric care suggests the need for targeted interventions and strategies to enhance communication, ultimately benefiting patients and increasing job satisfaction among clinicians. The study underlines the importance of fostering work environments that prioritize collaboration and open communication to enhance the overall quality of care and promote the professional satisfaction of clinicians within the broader practice work environment.

Authors contributions

The study design involved the participation of all authors. Data collection was performed by IR, who is also the main author of the manuscript as well as by AO and MSE. Data analysis was performed by IR with the final themes and findings formulated by IR, AO, CT, and MSE. All authors have contributed to the manuscript editing and have reviewed and approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for each clinician who took the time to participate in the study. We also thank Lars Nylander for his invaluable help in creating .

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analyzed for the current study are not publicly available, making them available would jeopardize the participating clinicians’ confidentiality. The researchers have no ethical permission to share them. The corresponding author can be contacted if someone wishes to request the study data.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AFS2015:4, 2015:4. (2016). https://www.av.se/globalassets/filer/publikationer/foreskrifter/engelska/organisational-and-social-work-environment-afs2015-4.pdf

- Anselmann, V., & Disque, H. (2022). Nurses’ perspective on team learning in interprofessional teams. Nursing Open, 10(4), 2142–2149. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1461

- Aylott, L. M. E., Tiffin, P. A., Saad, M., Llewellyn, A. R., & Finn, G. M. (2019). Defining professionalism for mental health services: A rapid systematic review. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 28(5), 546–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1521933

- Barnard, R., Jones, J., & Cruice, M. (2020). Communication between therapists and nurses working in inpatient interprofessional teams: Systematic review and meta-ethnography. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(10), 1339–1349. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1526335

- Boev, C., Tydings, D., & Critchlow, C. (2022). A qualitative exploration of nurse-physician collaboration in intensive care units. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 70, 103218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2022.103218

- Bok, C., Ng, C., Koh, J., Ong, Z., Ghazali, H., Tan, L., Ong, Y., Cheong, C., Chin, A., Mason, S., & Krishna, L. (2020). Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02296-x

- Bonciani, M., Schäfer, W., Barsanti, S., Heinemann, S., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2018). The benefits of co-location in primary care practices: The perspectives of general practitioners and patients in 34 countries. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2913-4

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Is thematic analysis used well in health psychology? A critical review of published research, with recommendations for quality practice and reporting. Health Psychology Review, 17(4), 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2022.2161594

- Connelly, L. M. (2016). Trustworthiness in qualitative research. MedSurg Nursing, 25(6), 435–437.

- Daheshi, N., Alkubati, S. A., Villagracia, H., Pasay-An, E., Alharbi, G., Alshammari, F., Madkhali, N., & Alshammari, B. (2023). Nurses’ perception regarding the quality of communication between nurses and physicians in emergency departments in Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional study. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 11(5), 645. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11050645

- Dolese, M. J., Kozbelt, A., & Hardin, C. (2014). Art as communication: Employing Gricean principles of communication as a model for art appreciation. The International Journal of the Image, 4(3), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v04i03/44133

- Draper, J. (2015). Ethnography: Principles, practice and potential. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 29(36), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.36.36.e8937

- Etherington, C., Wu, M., Cheng-Boivin, O., Larrigan, S., & Boet, S. (2019). Interprofessional communication in the operating room: A narrative review to advance research and practice. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia = Journal Canadien D’anesthesie, 66(10), 1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01413-9

- Foronda, C., MacWilliams, B., & McArthur, E. (2016). Interprofessional communication in healthcare: An integrative review. Nurse Education in Practice, 19, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.04.005

- Friedman, O. R. (2021). Exploring communication between staff and clinicians on an inpatient adolescent psychiatric unit.

- Friese, C. R., Lake, E. T., Aiken, L. H., Silber, J. H., & Sochalski, J. (2008). Hospital nurse practice environments and outcomes for surgical oncology patients. Health Services Research, 43(4), 1145–1163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00825.x

- Gabrielsson, S., Looi, G. E., Zingmark, K., & Sävenstedt, S. (2014). Knowledge of the patient as decision‐making power: Staff members’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration in challenging situations in psychiatric inpatient care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(4), 784–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12111

- Gleeson, L., O’Brien, G. L., O’Mahony, D., & Byrne, S. (2023). Interprofessional communication in the hospital setting: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 37(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2022.2028746

- Kanerva, A., Kivinen, T., & Lammintakanen, J. (2015). Communication elements supporting patient safety in psychiatric inpatient care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(5), 298–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12187

- Karlsson, A.-C., Gunningberg, L., Bäckström, J., & Pöder, U. (2019). Registered nurses’ perspectives of work satisfaction, patient safety and intention to stay: A double-edged sword. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(7), 1359–1365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12816

- Lake, E. T. (2002). Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Research in Nursing & Health, 25(3), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10032

- Lake, E. T., Sanders, J., Duan, R., Riman, K. A., Schoenauer, K. M., & Chen, Y. (2019). A meta-analysis of the associations between the nurse work environment in hospitals and 4 sets of outcomes. Medical Care, 57(5), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000001109

- Ma, C., Park, S. H., & Shang, J. (2018). Inter- and intra-disciplinary collaboration and patient safety outcomes in U.S. acute care hospital units: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 85, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.05.001

- Manojlovich, M. (2005). Linking the practice environment to nurses’ job satisfaction through nurse-physician communication. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 37(4), 367–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00063.x

- Morgan, D. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984287

- Morgan, D. (1998). Planning focus groups. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328171

- Morgan, D. L., & Bottorff, J. L. (2010). Advancing our craft: Focus group methods and practice. Qualitative Health Research, 20(5), 579–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310364625

- Morgan, S., Pullon, S., & McKinlay, E. (2015). Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(7), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008

- Moudatsou, M., Stavropoulou, A., Philalithis, A., & Koukouli, S. (2020). The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 8(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010026

- Nguyen, J., Smith, L., Hunter, J., & Harnett, J. (2019). Conventional and complementary medicine health care practitioners’ perspectives on interprofessional communication: A qualitative rapid review. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 55(10) https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55100650

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Noyes, A. L. (2022). Navigating the hierarchy: Communicating power relationships in collaborative health care groups. Management Communication Quarterly, 36(1), 62–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/08933189211025737

- Park, S. H., Hanchett, M., & Ma, C. (2018). Practice environment characteristics associated with missed nursing care. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 50(6), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12434

- Paxino, J., Denniston, C., Woodward-Kron, R., & Molloy, E. (2022). Communication in interprofessional rehabilitation teams: A scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(13), 3253–3269. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1836271

- Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63(4), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399

- Recto, P., Lesser, J., Zapata, J., Paleo, J., Gray, A. H., Zavala Idar, A., Castilla, M., & Gandara, E. (2023). Teaching person-centered care and interprofessional collaboration through a virtual mental health world café: A mixed methods IPE pilot project. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 44(8), 702–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2023.2212780

- Rochester, M. R. (2017). Synchronous communication and its effects on the collaboration of professional workplace employees engaged in a problem activity.

- Rousseau, C., Pontbriand, A., Nadeau, L., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2017). Perception of interprofessional collaboration and co-location of specialists and primary care teams in youth mental health. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal De L’Academie Canadienne De Psychiatrie De L’enfant Et De L’adolescent, 26(3), 198–204.

- Sabone, M., Mazonde, P., Cainelli, F., Maitshoko, M., Joseph, R., Shayo, J., Morris, B., Muecke, M., Wall, B. M., Hoke, L., Peng, L., Mooney-Doyle, K., & Ulrich, C. M. (2020). Everyday ethical challenges of nurse-physician collaboration. Nursing Ethics, 27(1), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019840753

- Sun, A. Y., Wright, S. M., & Miller, L. (2023). Clinical excellence in child and adolescent psychiatry: Examples from the published literature. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 27(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2022.2144748

- Umberfield, E., Ghaferi, A. A., Krein, S. L., & Manojlovich, M. (2019). Using incident reports to assess communication failures and patient outcomes. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 45(6), 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.02.006

- Vähätalo, L., Siukola, A., Atkins, S., Reho, T., Sumanen, M., Viljamaa, M., & Sauni, R. (2022). Cooperation between public primary health care and occupational health care professionals in work ability-related health issues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911916

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study: Qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

- Vatn, L., & Dahl, B. M. (2022). Interprofessional collaboration between nurses and doctors for treating patients in surgical wards. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1890703

- Vega, H., & Hayes, K. (2019). Blending the art and science of nursing. Nursing, 49(9), 62–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000577752.54139.4e

- Wei, H., Corbett, R. W., Ray, J., & Wei, T. L. (2020). A culture of caring: The essence of healthcare interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1641476

- Wener, P., Leclair, L., Fricke, M., & Brown, C. (2022). Interprofessional collaborative relationship-building model in action in primary care: A secondary analysis. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3, 890001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.890001

- Wilkinson, S. (1998). Focus group methodology: A review. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1(3), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.1998.10846874

- Yukl, G. (2008). How leaders influence organizational effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(6), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.09.008

- Zeleníková, R., Jarošová, D., Plevová, I., & Janíková, E. (2020). Nurses’ perceptions of professional practice environment and its relation to missed nursing care and nurse satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113805

- Zheng, Z., Gangaram, P., Xie, H., Chua, S., Ong, S. B. C., & Koh, S. E. (2017). Job satisfaction and resilience in psychiatric nurses: A study at the Institute of Mental Health, Singapore. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26(6), 612–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12286

Appendix 1:

Semi-structured interview guide—focus group interviews

Communication:

Characteristics of good and bad communication.

Communication methods of different professions.

The collaboration:

Experience of collaboration between professional groups.

Change/improvement proposal.

Leadership:

The role of leadership in interprofessional communication.

Impact on collaboration within the workgroup.

Responsibility:

Experiences of responsibility and workload.

Hierarchies/Power relationships:

Identification and experience of hierarchies/power structures.

Description and personal experiences.

Working environment:

Experiences of factors affecting work environment and job satisfaction.

Table 1. Description of participant distribution by profession.

Table 2. Steps in the analysis process—example.