Abstract

Stigmatised attitudes are known to be associated with negative outcomes in schizophrenia, yet there is little focus on the role of stigma in the recovery process. Attempts to develop interventions to reduce self-stigma in schizophrenia have not been found effective. This paper presents a theoretical integration based on a narrative review of the literature. PsycINFO, Medline and Embase databases were searched up to the 11th December 2023. Studies were included if they were: i) empirical studies using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies investigating mental health stigma; ii) included participants based in the United Kingdom, fluent in English, between the ages of 16 and 70, meeting criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. Fourteen studies were included. In Part 1, we propose a novel theoretical model derived from a synthesis of service-user perspectives on the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia. Stigmatised attitudes were commonly perceived to be caused by a lack of education and further exacerbated by disinformation primarily through the media and cultural communities. Stigma led to negative self-perceptions, negative emotional responses, social isolation and increased symptom severity, ultimately acting as a barrier to recovery. In Part 2, we identify several factors that ameliorate the impact of stigma and promote clinical and subjective recovery among service-users: education, empowerment, self-efficacy, self-acceptance, hope and social support. We argue that the notion of stigma resistance may be helpful in developing new interventions aimed at promoting recovery in individuals with schizophrenia. Wider implications are discussed and recommendations for future research and practice are explored.

Introduction

Stigma has been identified by researchers as one of the greatest barriers to recovery in serious mental illness (Yanos et al., Citation2020) due to its significant adverse effects across psychosocial, functional and clinical domains (Sarraf et al., Citation2022). Despite this, there is little emphasis on the role of stigma in recovery among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. This is particularly true within the United Kingdom (UK) where there are few studies investigating this phenomenon and therefore, there is little understanding to guide interventions. To date, there are no standardised educational materials for service users or service providers regarding the impact stigma has on severe mental illness or ways in which its effects can be reduced. The present theoretical review will be presented in two parts; Part 1 will propose a novel conceptualisation of the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia developed utilising UK service-user perspectives. Part 2 will conceptualise a framework of recovery through the components of stigma resistance. Our aim in this paper is to consider the role of stigma as an important, and potentially modifiable, factor related to recovery in schizophrenia. As described below, stigma has been identified as a salient factor in schizophrenia across a broad range of studies.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental illness that affects the individual’s thoughts, feelings and behaviours, ultimately impairing their perception of reality (World Health Organization, Citation2019). The psychiatric disorder is characterised by an array of symptoms which are mainly categorised as positive, negative and cognitive (McCutcheon et al., Citation2020). Positive symptoms encapsulate the presence of symptoms which alter how the individual thinks, acts and experiences the world; these include hallucinations, delusions, thought disorder and movement disorder (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Negative symptoms refer to the absence or diminution of healthy mental functioning, including a lack of interest and pleasure, a lack of motivation, low energy, social withdrawal and flattened affect (Mäkinen et al., Citation2008). Cognitive symptoms include poor executive functioning, poor concentration, difficulties focusing and an impeded working memory; cognitive symptoms affect approximately 80% of individuals with the diagnosis whereas negative symptoms affect nearly 40% (Carbon & Correll, Citation2014). Positive symptoms, on the other hand, must be evident for a diagnosis. It must be accompanied by one other symptom: another positive symptom, a negative symptom, grossly disorganised behaviour or catatonic behaviour. The disturbances must have been evident for at least one month, impeding the individuals’ level of functioning (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2019).

Schizophrenia affects approximately 1 in 300 people worldwide (Global Health Data Exchange, Citation2019). The typical age of onset, like many other neuropsychiatric diseases, is late adolescence or early twenties in males and slightly later in females (Radua et al., Citation2018). The aetiology of schizophrenia is multifactorial (Stilo & Murray, Citation2019) and reflects an interaction between genetic vulnerability and environmental factors (McCutcheon et al., Citation2019). For example, trauma, social isolation and migration were identified as environmental factors that may influence an individual’s likelihood of developing the disorder (Stilo & Murray, Citation2019). Moreover, findings indicate an increased incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia among groups consisting of migrants, ethnic minorities and refugees (Hollander et al., Citation2016; van der Ven & Selten, Citation2018) and those with lower socioeconomic status (Luo et al., Citation2019). This is particularly relevant for UK service users due to the high prevalence of migrants and ethnic minorities presenting to UK mental health services (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, Citation2021).

Stigma in schizophrenia

Despite the recent drift towards greater mental health literacy (Wood et al., Citation2014) and the national shift in perception regarding psychiatric illness (Henderson et al., Citation2019), individuals diagnosed with psychiatric disorders continue to be misrepresented and misunderstood by the general public, often becoming the targets of stigma (Thornicroft et al., Citation2019). Stigma encapsulates the negative actions and behaviours aimed at individuals who are deemed to be of low social status; such behaviours include discrimination, stereotyping and social distancing (Hoftman, Citation2017; Link & Phelan, Citation2001). In England, as indicated by a range of health, social, and economic indices, stigma and discrimination against people with mental illnesses have a significant public health impact: reduced access to healthcare (Memon et al., Citation2016), higher mortality rates (Mansour et al., Citation2020), reduced life expectancy (Chang et al., Citation2011; Chesney et al., Citation2014), exclusion from employment (Silver, Citation2017), greater risk of targeted violence (Clement et al., Citation2011), poverty (Boardman et al., Citation2015) and homelessness (Bramley & Fitzpatrick, Citation2017). The high prevalence of mental health stigma evidenced today prompted the Lancet Commission’s report on ending stigma and discrimination in mental health (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022), which recognised stigma as a serious impediment to social inclusion and citizenship, resulting in an infringement of fundamental human rights. This is particularly true for schizophrenia, which is recognised as one of the most misunderstood and stigmatised psychiatric diagnoses, resulting in an increased prevalence of self-stigma among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (Pescosolido et al., Citation2019; Valery & Prouteau, Citation2022).

Although trends seem to indicate a decline in stigma at a societal level towards mental illness (Henderson et al., Citation2019), the rate of decline in negative attitudes towards schizophrenia does not match that of other psychiatric conditions such as depression and anxiety; schizophrenia continues to be associated with the most negative stereotypes (Wood et al., Citation2014), such as the potential for violence, which has increased since the 1990s (Pescosolido et al., Citation2019). Research has demonstrated that stigmatised attitudes, presumably caused by a lack of education and misinformation (Shrivastava et al., Citation2012), can impact the trajectory of the illness (Mueser et al., Citation2020). Stigma is therefore perceived as a barrier to recovery in schizophrenia (Lysaker et al., Citation2012). For example, perceived discrimination was positively associated with the prevalence of delusional ideation (Janssen et al., Citation2003) and the frequency of psychotic experiences (Stickley et al., Citation2019). Research has also indicated that perceived stigma is associated with lower subjective wellbeing, diminished psychosocial functioning and less perceived recovery among individuals with psychosis (Mueser et al., Citation2020), with comparable conclusions drawn from studies conducted specifically among people with schizophrenia (Landeen et al., Citation2007; Lysaker et al., Citation2006; Magallares et al., Citation2016). These findings illustrate the potentially damaging consequences of stigma for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Public-stigma & self-stigma

As a consequence of public stigma—which refers to stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination from the general population (Corrigan & Watson, Citation2002), individuals diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder may develop self-stigma; their identity may be devalued due to an internalisation of the negative stereotypes, ultimately agreeing with the stigmatised attitudes (Corrigan & Rao, Citation2012). The term internalised stigma is used interchangeably with self-stigma throughout the literature (Mittal et al., Citation2012); for consistency, we will use the latter term in this paper. Evidence consistently demonstrates the negative role self-stigma plays in the course of the illness leading to poorer clinical and functional outcomes (Dubreucq et al., Citation2021). In schizophrenia, this includes increased severity of symptoms (Maharjan & Panthee, Citation2019), poorer treatment adherence (Yılmaz & Okanlı, Citation2015), social isolation (Karidi et al., Citation2015), impaired community functioning (Schwarzbold et al., Citation2021), decreased quality of life (Lien et al., Citation2017; Picco et al., Citation2016) and increased risk of suicide (Vrbova et al., Citation2017). A recently published review determined that individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia experience high levels of self-stigma globally, ranging from 32.6% to 44.2% (Dubreucq et al., Citation2021).

The most significant variation in rates of self-stigma appears to be across cultures (Yu et al., Citation2021). Research has consistently demonstrated higher levels of public stigma towards individuals with schizophrenia in eastern countries compared to western countries, irrespective of the countries’ level of development (Dubreucq et al., Citation2021; Krendl & Pescosolido, Citation2020). These variations across cultures seem to reflect collectivist societal norms; individuals from these cultures are more likely to attribute mental illness to moral or supernatural influences, which was, therefore, likely to impact the families’ social and economic status (Girma et al., Citation2013; Ibrahim et al., Citation2016; Krendl & Pescosolido, Citation2020); eliciting shame for not meeting social expectations (Koschorke et al., Citation2014; Yang et al., Citation2014). Despite the cultural disparities in prevalence, the clinical and psychosocial outcomes of self-stigma appear to be consistent across countries (Sarraf et al., Citation2022). As the UK is a multicultural society, a great variety of ethnicities present to UK mental health services (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities, Citation2021). Therefore, in order to provide an insight into the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia as perceived by service users, the multi-cultural discrepancies within the data must be considered.

Stigma resistance

Despite the high prevalence, many individuals are able to mitigate the effects of stigma through stigma resistance, which refers to one’s capacity to challenge, counteract or resist stigmatising beliefs (Ritsher et al., Citation2003). According to researchers, individuals are able to challenge stigma by adopting a meaningful social identity separate from the illness (Firmin et al., Citation2016; Marcussen et al., Citation2021; Thoits, Citation2011). Stigma resistance was linked to lower overall symptoms of schizophrenia, including positive, negative and mood symptoms; greater illness insight, hope, self-efficacy, quality of life and recovery (Firmin et al., Citation2016). Stigma resistance was also positively associated with self-esteem and social functioning—two factors conducive to a positive prognosis, increased subjective well-being and reduced recovery time (O'Connor et al., Citation2018).

Self-stigma interventions

Existing self-stigma interventions for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia mainly include psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness-based therapies and assertiveness training (Luo et al., Citation2022). However, the few studies that researched the effectiveness of these interventions lacked consistency in their findings and were contradictory (Fung et al., Citation2011; Morrison et al., Citation2016; Wood et al., Citation2016; Yanos et al., Citation2010). Subsequently, a recent meta-analysis concluded that the existing interventions had no significant effect on self-stigma (Luo et al., Citation2022); as a result, the effectiveness of self-stigma interventions for individuals with schizophrenia remains unclear. Although research into the relationship between stigma and mental illness has recently gained more precedence (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022), there are very few studies exploring the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia through the lens of recovery and even fewer within a UK context. Therefore, we aimed to critically review UK service user experiences of stigma, outline the impact it has on the course of the illness and identify the key features conducive to recovery.

Defining recovery

Scholars consistently characterise recovery from mental illness as a multidimensional process (Jacob et al., Citation2017). Clinical recovery is a term used by scholars and clinicians to refer to symptomatic remission, whereby the individual returns to earlier levels of functioning—evident across individual, social and occupational domains (Van Eck et al., Citation2017). By contrast, the definition of subjective recovery evolved through service user and family member input to emphasise living a meaningful and optimistic life despite constraints created by mental illness (Chan et al., Citation2017). Subjective recovery is used synonymously with the term personal recovery throughout the literature (Galliot et al., Citation2022). It led to the development of the CHIME conceptual framework of recovery, which encapsulates “connectedness, hope and optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life, and empowerment” (Leamy et al., Citation2011, p. 449).

Part 1: A conceptual model for understanding the impact of stigma on individuals with schizophrenia

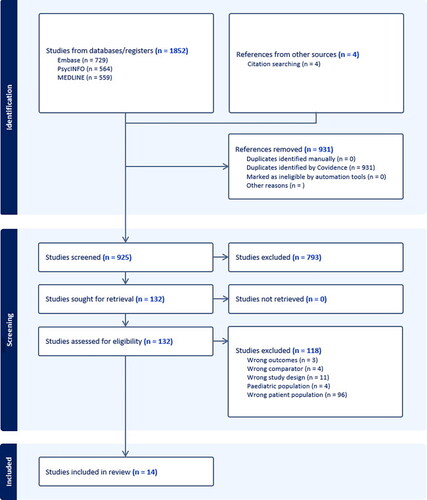

In Part 1, we present a theoretical model derived from a synthesis of evidence of service-user perspectives drawn from both qualitative and quantitative sources, based on a narrative review of the literature on stigma and schizophrenia in the UK. To identify relevant literature, searches were conducted across PsycINFO, Medline and Embase databases up to December 2023. Criteria were i) empirical studies using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies investigating mental health stigma; ii) study includes participants based in the United Kingdom, fluent in English, between the ages of 16 and 70, meeting criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. Studies were excluded if participants were exclusively under the age of 18. Fourteen studies met the inclusion criteria. A PRISMA flowchart is available in Appendix A. Details of included studies are presented in Appendix B.

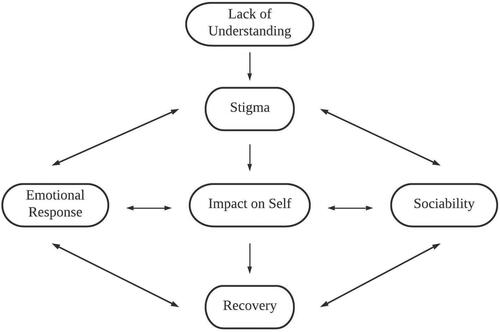

Our aim was to conceptualise the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia. In summary, service-users highlighted a lack of understanding as the predominant cause of stigma in schizophrenia (e.g. Ahmed et al., Citation2020). Subsequently, stigma led to negative emotional responses such as shame and hopelessness, and decreased sociability. It also impacted individuals’ sense of self; causing service-users to identify with the negatively perceived diagnosis which often resulted in poor self-esteem. This appeared to exacerbate the negative emotional responses and further strengthen the desire to distance themselves from others—further increasing their level of self-stigma. Emotional responses and sociability appeared to have bi-directional relationships with both subjective and clinical recovery. Negative emotions and social marginalisation associated with stigma impeded recovery, whereas positive emotions and social inclusion were conducive to recovery, promoting stigma resistance. Our conceptual diagram is presented in . Below, we expand on each of the concepts in the diagram.

Service-user insights

Stigma: A multifaceted construct

To date, UK service users who have participated in research investigating the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia, all reported experiencing stigma as a consequence of their mental health diagnosis (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Berry & Greenwood, Citation2018; Burke et al., Citation2016; Farrelly et al., Citation2014; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Thornicroft et al., Citation2009; Vass et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2017, Citation2022; Wood & Irons, Citation2017). Moreover, they all identified stigma as a factor that impacted the course of the illness. However, the ways in which they arrived at this conclusion differed. The majority of the studies examined the effects of experienced stigma, two studies compared the effects of experienced stigma to anticipated stigma, and two investigated the impact of self-stigma. Subsequently, stigma appears to be a multi-faceted construct that is made up of multiple components which ultimately affected the individual’s experience of severe mental illness. Firstly, both experiments investigating the relationship between experienced stigma and anticipated stigma reported a positive association between the two (Farrelly et al., Citation2014; Thornicroft et al., Citation2009). The degree of experienced stigma and anticipated stigma correlated across all domains apart from employment (Farrelly et al., Citation2014; Thornicroft et al., Citation2009), education (Farrelly et al., Citation2014) and close personal relationships (Thornicroft et al., Citation2009). In these domains, the level of anticipated stigma was significantly higher than the level of experienced stigma. Moreover, in a global context, participants in the UK were more likely to report greater levels of anticipated stigma (Thornicroft et al., Citation2009). Although there were no significant differences of experienced stigma relating to age or sex (Farrelly et al., Citation2014; Thornicroft et al., Citation2009), older service users and female service users reported greater levels of anticipated stigma (Farrelly et al., Citation2014). Increased levels of experienced stigma were associated with a higher level of education and mixed ethnicity (Farrelly et al., Citation2014).

Lack of understanding

Another factor that impacted the level of experienced stigma was culture; participants from western cultures experienced lower levels of discrimination (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Thornicroft et al., Citation2009; Wood et al., Citation2022). People of South Asian heritage living in the UK perceived individuals with psychosis as more angry and more dangerous than those without a mental illness. They were more willing than the White British respondents to participate in avoidance behaviours, withhold help and disclosed greater support for segregation between people with psychosis and the general public (Ahmed et al., Citation2020). Similarly, ethnic minority respondents presenting to UK services all highlighted their experience with psychosis as being highly stigmatised, mostly ascribing the stigma they experienced to cultural beliefs which were embedded within their family network. For example, one service user explained that mental health concerns were considered a sign of weakness in his culture. Another said there was no term for psychiatric hospital in his language; the closest word was rehabilitation, which literally translated to “crazy house” (Wood et al., Citation2022, p. 14). The researchers identified family support as one of the most important protective factors against stigma; service users who were able to talk openly with their families about their experiences and were provided with support, were better able to manage their experience of psychosis and the stigma attached to it (Wood et al., Citation2022).

A lack of understanding regarding schizophrenia appeared to be a major contributing factor in stigma which seemed to be exacerbated by the portrayal of psychosis in the media (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). Across these five qualitative studies, most participants raised concerns regarding negative media content and the media’s propagation of stereotypes, often describing the media as a weapon for reinforcing violent imagery. Multiple service users recalled newspaper articles related to schizophrenia—all of which reported murders or violent crimes. Moreover, many participants highlighted the over-emphasis of negative content, drawing attention to the lack of media content related to positive outcomes. Most service users voiced their frustrations regarding the media’s coverage of schizophrenia and acknowledged the impact it had on the general public’s stigmatised perceptions of psychosis. Findings drawn from another qualitative study identified misconceptions associated with schizophrenia, including the belief that psychosis and psychopathy were synonymous and that schizophrenia was often confused with dissociative identity disorder (Burke et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, a few service users explicitly mentioned the lack of educational materials that are available; a lack of information at the point of diagnosis seemed to result in a more negative experience of psychosis, negatively impacting the trajectory of the illness (Pitt et al., Citation2009). Conversely, those who had a greater understanding of schizophrenia had a more optimistic outlook and demonstrated traits of self-efficacy (Burke et al., Citation2016; Pitt et al., Citation2009).

Impact on the self

Receiving a diagnosis was described by several service users as a relief; the diagnosis validated their distress and allowed them to receive greater support and understanding from family and friends. This allowed individuals to externalise their difficulties through the diagnosis instead of taking personal responsibility for them (Burke et al., Citation2016; Pitt et al., Citation2009). Some service users believed that viewing their upsetting experiences as the product of an illness distinct from themselves was beneficial (Pitt et al., Citation2009). However, some also saw the diagnosis as a label, casting them into a negatively viewed group (Burke et al., Citation2016; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013). For example, one service user described a painful sensation of difference and abnormality after experiencing psychosis and being labelled "mentally ill", another said she now felt "different" from others, "like a fish out of water" which impeded her ability to interact with others (Burke et al., Citation2016, p. 136). This sometimes led to the development of a new identity as a "schizophrenic" (Pitt et al., Citation2009, p. 421) which alluded to the idea that persons suffering from psychosis were seen as “second-class citizen[s]” (Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013, p. 199). Multiple service users described feeling powerless as a result of their diagnoses (Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013), with some interpretating it as a "prognosis of doom" due to the lack of information provided at the point of diagnosis (Pitt et al., Citation2009, p. 422).

Self-esteem was another measure of self-image that was negatively impacted (Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Vass et al., Citation2015, Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2017, Citation2022). Many service users discussed their reduced levels of self-esteem as a consequence of stigma (Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Wood et al., Citation2022). This was supported through correlational analyses which demonstrated a negative relationship between stigma and self-esteem (Vass et al., Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2017). Moreover, further analyses indicated that self-esteem mediated the association between stigma and recovery (Vass et al., Citation2015; Wood et al., Citation2017), depression and hopelessness (Wood et al., Citation2017). Stigma associated with schizophrenia also led to feelings of worthlessness, lowered expectations (Burke et al., Citation2016; Wood et al., Citation2022) and a loss of confidence (Burke et al., Citation2016; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Wood et al., Citation2022). On the other hand, service users identified self-acceptance as a protective factor; some reported developing an understanding for themselves and others in similar situations as a result of their lived experiences with psychosis and the stigma associated with it. Offering assistance and understanding to others was stated to boost self-acceptance and self-esteem (Burke et al., Citation2016).

Emotional response

As a result of stigma, many service users expressed feelings of shame associated with their mental illness (Burke et al., Citation2016; Wood et al., Citation2022). Correlational experiments concluded that stigma had a positive association with shame (Wood et al., Citation2017; Wood & Irons, Citation2017). Moreover, further analyses indicated that shame mediated the relationship between stigma and depression (Wood et al., Citation2017; Wood & Irons, Citation2017) and hopelessness and recovery (Wood et al., Citation2017). Hopelessness was another emotional consequence linked to stigma (Berry & Greenwood, Citation2018; Burke et al., Citation2016; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Vass et al., Citation2015; Wood et al., Citation2017). Stigma predicted hopelessness (Wood et al., Citation2017) and mediated the relationship between self-stigma, vocational activity, social inclusion (Berry & Greenwood, Citation2018) and recovery (Vass et al., Citation2015). Other emotional responses discussed by participants in relation to stigma included guilt and self-blame, preoccupation and worry (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Vass et al., Citation2015; Wood et al., Citation2022), fear and vulnerability (Burke et al., Citation2016; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Wood et al., Citation2022), anger and frustration (Burke et al., Citation2016; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Vass et al., Citation2015; Wood et al., Citation2022).

Sociability

The most common issue emerging from qualitative research of service users’ perspectives on discrimination was social exclusion; this theme was evident in all qualitative studies that examined the relationship between stigma and schizophrenia among UK service users (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). Words synonymous with “excluded” (Rose et al., Citation2011, p. 197) and “rejected” (Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013, p. 201) were the most frequently mentioned. Respondents indicated that they began to actively withdraw from society, choosing to engage in avoidance behaviour to prevent experiencing stigma and its negative consequences—social withdrawal was another key theme evident in the qualitative studies. Social avoidance was predicted by internalised stigma at a 6-month follow up (Vass et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, the positive relationship between the two variables appeared stronger as people aged (Berry & Greenwood, Citation2018). Similarly, many service users actively avoided forming new relationships due to risks of rejection (Burke et al., Citation2016; Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). Peer support was identified as a protective factor against stigma; for example, one individual explained how meeting other people with psychosis helped her feel less ashamed and more hopeful (Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013). Peer support encouraged the willingness of service users to talk openly about their diagnoses and helped to change the preconceptions of those they met. Despite the stigma and discrimination, individuals with peer support went on to hold valuable positions in both volunteer work and paid employment (Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013).

Recovery

Many service users explained that stigma and their psychotic experiences were connected and had negative consequences for one another; one individual referred to it as “a vicious cycle” (Wood et al., Citation2022, p. 17), another specified how it fuelled feelings of paranoia and another described how it triggered an increase of intensity and frequency of auditory hallucinations (Burke et al., Citation2016). These findings were supported by data drawn from experimental designs which demonstrated that positive symptoms of schizophrenia were correlated with experienced and internalised stigma (Vass et al., Citation2017; Wood & Irons, Citation2017). Mediation analyses indicated that internalised stigma predicted positive symptoms (Vass et al., Citation2015). Moreover, both experienced and internalised stigma predicted patient recovery (Wood et al., Citation2017; Wood & Irons, Citation2017). Mediators between stigma and personal recovery were identified as social rank (Wood & Irons, Citation2017), self-esteem and emotional distress (Wood et al., Citation2017). These findings were further supported by the service-user led group Recovery in the Bin, who highlighted discrimination as one of their core principles in the Unrecovery Star, citing it as a societal issue that hinders recovery and sustains psychological distress (Recovery in the Bin, Citation2016).

Part 2: Targets for stigma resistance

In Part 2, we present the key features conducive to clinical and subjective recovery, identified from the synthesis of evidence of service-user perspectives in Part 1. Our aim is to conceptualise a framework for recovery through the components of stigma resistance. This is depicted in . The components that comprise the diagram are explained below.

Figure 2. Diagram depicting the conceptual framework of recovery through the components of stigma resistance.

Empowerment & self-efficacy

UK service users expressed feeling disempowered due to their internalised illness identity which led to feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness, ultimately acting as a barrier to recovery (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). Therefore, we believe that empowering individuals with schizophrenia may encourage them to engage in behaviours that are conducive to recovery. This idea was conveyed by WHO (Citation2010) and Thornicroft et al. (Citation2022), highlighting the importance of empowerment for recovery among individuals with a psychiatric illness. According to service-users, services that encouraged information-sharing and decision-making empowered them, allowing them to reclaim their lives and feel hopeful about their futures (WHO, Citation2010). This is particularly relevant as empowerment and self-efficacy were both identified as factors that mediate the relationship between schizophrenia and self-stigma (Vauth et al., Citation2007).

To optimise an individual’s degree of empowerment, self-efficacy should be promoted (Rawlett, Citation2014). Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to complete a task or achieve a goal (Bandura, Citation1997). Through self-efficacy, service users are able to develop a competent sense of self, further facilitating the process of recovery (Mancini, Citation2007). According to Wood and Bandura (Citation1989, p. 365), self-efficacy can be improved with “realistic encouragement”—service providers should incorporate this into daily practice. For example, mental health professionals could inspire confidence among service users by encouraging their capability for autonomy and decision-making during therapeutic engagement.

Self-acceptance

As a person’s sense of self-efficacy grows, they begin to feel more confident and capable, leading to an improved self-image and increased perception of control; the internalised negative illness identity may then begin to shift - the individual may dismiss the term totally or reframe it to express good attributes (Chamberlin, Citation1997). Among individuals with psychosis, self-acceptance appeared to result in empowered action, ultimately promoting recovery (Waite et al., Citation2015). This idea was conceptualised by Gumley et al., (Citation2010) who introduced the compassion focused model of recovery after psychosis; they suggested that compassionate responding in the form of self-acceptance lessens the impact of self-criticism and promotes recovery. We therefore argue that this shift in attitude should be encouraged by service providers. For example, providing information regarding their diagnosis and emotional support was evidenced to improve the self-esteem of service users with severe mental illness (Ebrahimi et al., Citation2014). By increasing an individual’s self-esteem, an individual’s level of self-acceptance also increases, thereby improving psychological wellbeing (Macinnes, Citation2006) and promoting recovery (Frank & Davidson, Citation2014).

Hope

Service users often cited hope as the catalyst that aided their recovery and provided a psychological buffer in the face of stigma. Similar trends between hope, stigma and recovery from psychosis have been observed across cultures (Avdibegović & Hasanović, Citation2017; Sari et al., Citation2021). As hopefulness is conducive to recovery (Acharya & Agius, Citation2017), steps should be taken to promote hope for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Evidence has indicated that positivity is indicative of hope (Duggal et al., Citation2016), this would imply that increasing positivity among service users will also enhance their likelihood of experiencing hopefulness (Stewart, Citation2020). Positive framing is a communication device that has been evidenced to elicit hope among individuals recovering from illness; by wording information in a specific way, the information is more likely to be perceived in a positive light (Kothari, Citation2007). For example, stating that 60% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia continued to report symptomatic remission after 1 year of treatment, would be a more positive way of stating that 4 out of 10 patients continue to experience psychotic symptoms 1 year after treatment (Li et al., Citation2022). Further evidence suggests that having a more positive perspective on psychotic experiences can help protect individuals against the effects of stigma (Brett et al., Citation2013). Involving individuals with lived experience of schizophrenia in developing recovery-focussed psychoeducation materials, with information worded in a positive manner, could help service-users to feel more hopeful, particularly soon after diagnosis as service-users described this as a time when they felt hopeless (e.g. Pitt et al., Citation2009). This is an important and straightforward target for intervention which could have profound impacts, since hope is positively associated with quality of life (Vrbova et al., Citation2017).

Social support

All of the UK service users who participated in qualitative studies investigating the relationship between schizophrenia and self-esteem had experienced social exclusion from family, friends or the workplace, eventually resulting in social withdrawal (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). This is despite discrimination against schizophrenia being considered unlawful under the Equality Act 2010. Although no studies measuring the relationship between social isolation and symptom severity have been conducted among UK service users, a longitudinal study demonstrated that social isolation was associated with increased symptom severity for positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Vogel et al., Citation2021). This would suggest that preventing isolation and increasing social interaction is beneficial for long-term wellbeing and symptomatic improvement in schizophrenia. Many UK service users identified the role of social support in their perceptions of stigma. Peer support appeared to be vital in normalising the diagnosis and provided individuals with a psychological buffer against stigma. Meeting people who had similar diagnoses appeared to be extremely beneficial in terms of exchanging experiences and generating hope for the future (Forrester-Jones & Barnes, Citation2008; Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022). The effectiveness of promoting social engagement was evidenced in a recent umbrella review of 216 systematic reviews, which identified social contact as the most effective intervention for the reduction of stigmatisation among individuals diagnosed with a mental illness (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022).

Education

Service-users who were not provided with sufficient educational material at the point of diagnosis were more vulnerable to stigma and experienced an increased severity of symptoms throughout the course of their illness (Pitt et al., Citation2009). As individuals who search for information themselves are likely to be overwhelmed by the information available on the internet and may not understand it due to its literary content (Skierkowski et al., Citation2019), we believe that service-users should be provided with information regarding schizophrenia, stigma and stigma resistance, in an accessible and service-user-friendly format. As ethnic minorities presenting to UK services often attribute schizophrenia to supernatural or moral causes (Pitt et al., Citation2009; Pyle & Morrison, Citation2013; Rose et al., Citation2011; Wood et al., Citation2022), the biological underpinnings of mental illness should be emphasised in an attempt to reduce stigma within these communities. Moreover, as findings indicate that the negative consequences of stigma worsen with age (Berry & Greenwood, Citation2018), we believe that information will be most beneficial at the point of diagnosis.

According to a recent report, mental health expenditure costs the UK economy at least £177.9 billion annually (McDaid et al., Citation2022). It is widely understood that the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) impacts clinical and functional outcomes (Lysaker et al., Citation2012; Mueser et al., Citation2020) which in turn, may cost the NHS more money (Tsiachristas et al., Citation2016). A large body of evidence has demonstrated a positive association between stigma and DUP (Mueser et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we argue that information regarding schizophrenia, stigma and stigma resistance should be circulated to wider groups such as early intervention services in a further attempt to increase knowledge and possibly shorten the DUP. We believe this could be taken a step further by circulating psycho-educational materials to secondary school students as severe mental illnesses are not covered within the mental health section of the Personal, Social, Health and Economic [PSHE] education association curriculum (PSHE Association, Citation2023). These materials should be co-designed with young people, alongside people with lived experience of psychosis, clinicians and academics to raise awareness and reduce stigma.

Recommendations for future research and clinical practice

At the time of writing, we could not identify any UK based educational materials which specifically addressed the relationship between schizophrenia, stigma and recovery. In line with the Lancet Commission Recommendation 5 (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022, p. 34), we believe that healthcare professions should be provided with stigma reduction education. However, we also believe this could be extended to students, service users, their caregivers and their families. We suggest that this could be done in service-user-friendly and accessible formats that could be provided at the point of diagnosis.

The Medical Research Council framework proposes that complex interventions require research evidence and theory to guide their development (Skivington et al., Citation2021). We suggest that our theoretical integration of stigma resistance and subjective recovery could form a basis for future endeavours to develop new recovery-oriented interventions for schizophrenia, through the treatment target of increased stigma resistance. To be successful, such endeavours should involve collaboration with people with lived experience of schizophrenia. Initial steps could include qualitative research to better understand the potential relationships between stigma and recovery. Quantitative research utilising prospective designs is also required to investigate the impact of stigma on recovery over time. Patient and public engagement with service users, carers and clinicians is required to inform the potential clinical utility of interventions based around stigma resistance.

Conclusion

Schizophrenia continues to be one of the most highly stigmatised psychiatric diagnoses (Reneses et al., Citation2020), resulting in poorer clinical and functional outcomes (Dubreucq et al., Citation2021). Among UK service users, stigmatised attitudes are commonly perceived to be caused by a lack of education and further exacerbated by disinformation primarily through the media and cultural communities. Stigma can lead to negative self-perceptions, negative emotional responses, social isolation and increased symptom severity, ultimately acting as a barrier to recovery. We identified several factors that ameliorated the impact of stigma and promoted recovery among UK service users: education, hope, self-acceptance, empowerment, self-efficacy and social support. We theorise that providing the appropriate information at the point of diagnosis may aid newly diagnosed service-users in their recovery journey. As the effectiveness of current self-stigma interventions is in question, we suggest promoting education, hope, self-acceptance, empowerment, self-efficacy and social support in daily clinical practice, with the aim of improving stigma resistance. For example, mental health professionals could frame their interactions with patients based on the conclusions drawn in the present article to minimise self-stigma and promote recovery.

The protective factors we have identified mirror the five components of the CHIME framework for personal recovery in mental health as proposed by Leamy and colleagues (Citation2011)—further supporting our conceptualisation of schizophrenia, stigma and recovery. Although evidence indicates that the core components of recovery-orientated interventions are conducive to stigma resistance, their implementation is uncommon among self-stigma interventions (Thornicroft et al., Citation2022) Therefore, we argue that recovery-orientated interventions should be encouraged within clinical practice due to their emphasis on empowerment and hope, alongside clinical, functional and social domains (Winsper et al., Citation2020), to facilitate stigma resistance and to promote recovery.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acharya, T., & Agius, M. (2017). The importance of hope against other factors in the recovery of mental illness. Psychiatria Danubina, 29(3), 619–622.

- Ahmed, S., Birtel, M. D., Pyle, M., & Morrison, A. P. (2020). Stigma towards psychosis: Cross‐cultural differences in prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination in white British and South Asians. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 30(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2437

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Avdibegović, E., & Hasanović, M. (2017). The stigma of mental illness and recovery. Psychiatria Danubina, 29(5), 900–905.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

- Berry, C., & Greenwood, K. (2018). Direct and indirect associations between dysfunctional attitudes, self-stigma, hopefulness and social inclusion in young people experiencing psychosis. Schizophrenia Research, 193, 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.037

- Boardman, J., Dogra, N., & Hindley, P. (2015). Mental health and poverty in the UK – Time for change? BJPsych International, 12(2), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.1192/s2056474000000210

- Bramley, G., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2017). Homelessness in the UK: Who is most at risk? Housing Studies, 33(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344957

- Brett, C., Heriot-Maitland, C., McGuire, P., & Peters, E. (2013). Predictors of distress associated with psychotic-like anomalous experiences in clinical and non-clinical populations. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12036

- Burke, E., Wood, L., Zabel, E., Clark, A., & Morrison, A. P. (2016). Experiences of stigma in psychosis: A qualitative analysis of service users’ perspectives. Psychosis, 8(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2015.1115541

- Carbon, M., & Correll, C. (2014). Thinking and acting beyond the positive: The role of the cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. CNS Spectrums, 19(S1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852914000601

- Chamberlin, J. (1997). A working definition of empowerment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 20(4), 43–46.

- Chan, R. C., Mak, W. W., Chio, F. H., & Tong, A. C. (2017). Flourishing with psychosis: A prospective examination on the interactions between clinical, functional, and personal recovery processes on well-being among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(4), 778–786. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx120

- Chang, C.-K., Hayes, R. D., Perera, G., Broadbent, M. T., Fernandes, A. C., Lee, W. E., Hotopf, M., & Stewart, R. (2011). Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PloS One, 6(5), e19590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019590

- Chesney, E., Goodwin, G., & Fazel, S. (2014). Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: A meta-review. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20128

- Clement, S., Brohan, E., Sayce, L., Pool, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2011). Disability hate crime and targeted violence and hostility: A mental health and discrimination perspective. Journal of Mental Health, 20(3), 219–225. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.579645

- Corrigan, P., & Rao, D. (2012). On the self-stigma of mental illness: stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 57(8), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700804

- Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2002). Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1(1), 16–20.

- Dubreucq, J., Plasse, J., & Franck, N. (2021). Self-stigma in serious mental illness: A systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(5), 1261–1287. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa181

- Duggal, D., Sacks-Zimmerman, A., & Liberta, T. (2016). The impact of hope and resilience on multiple factors in neurosurgical patients. Cureus, 8(10), e849. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.849

- Ebrahimi, H., Navidian, A., & Keykha, R. (2014). Effect of supportive nursing care on self esteem of patients receiving electroconvulsive therapy: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Caring Sciences, 3(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.5681/jcs.2014.016

- Farrelly, S., Clement, S., Gabbidon, J., Jeffery, D., Dockery, L., Lassman, F., Brohan, E., Henderson, R. C., Williams, P., Howard, L. M., & Thornicroft, G, MIRIAD study group. (2014). Anticipated and experienced discrimination amongst people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-157

- Firmin, R. L., Luther, L., Lysaker, P. H., Minor, K. S., & Salyers, M. P. (2016). Stigma resistance is positively associated with psychiatric and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 175(1-3), 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.03.008

- Forrester-Jones, R., & Barnes, A. (2008). On being a girlfriend not a patient: The quest for an acceptable identity amongst people diagnosed with a severe mental illness. Journal of Mental Health, 17(2), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701498341

- Frank, D. M., & Davidson, L. (2014). The central role of self-esteem for persons with psychosis. The Humanistic Psychologist, 42(1), 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2013.771531

- Fung, K. M. T., Tsang, H. W. H., & Cheung, W. (2011). Randomized controlled trial of the self-stigma reduction program among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 189(2), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.02.013

- Galliot, G., Sanchez-Rodriguez, R., Belloc, A., Phulpin, H., Icher, A., Birmes, P., Faure, K., & Gozé, T. (2022). Is clinical insight a determinant factor of subjective recovery in persons living with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders? Psychiatry Research, 316, 114726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114726

- Girma, E., Tesfaye, M., Froeschl, G., Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., Dehning, S., & Müller, N. (2013). Facility based cross-sectional study of self stigma among people with mental illness: Towards patient empowerment approach. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 7(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-7-21

- Global Health Data Exchange. (2019). Institute for health metrics and evaluation. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/?params=gbd-api-2019

- Gumley, A., Braehler, C., Laithwaite, H., MacBeth, A., & Gilbert, P. (2010). A compassion focused model of recovery after psychosis. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.186

- Henderson, C., Potts, L., & Robinson, E. (2019). Mental illness stigma after a decade of Time to Change England: Inequalities as targets for further improvement. European Journal of Public Health, 30(3), 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa013

- Hoftman, G. (2017). The burden of mental illness beyond clinical symptoms: Impact of stigma on the onset and course of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal, 11(4), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2016.110404

- Hollander, A.-C., Dal, H., Lewis, G., Magnusson, C., Kirkbride, J. B., & Dalman, C. (2016). Refugee migration and risk of schizophrenia and other non-affective psychoses: Cohort study of 1.3 million people in Sweden. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 352, i1030. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1030

- Ibrahim, A., Hor, S., Bahar, O. S., Dwomoh, D., McKay, M. M., Esena, R. K., & Agyepong, I. A. (2016). Pathways to psychiatric care for mental disorders: A retrospective study of patients seeking mental health services at a public psychiatric facility in Ghana. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0095-1

- Jacob, S., Munro, I., Taylor, B. J., & Griffiths, D. (2017). Mental health recovery: A review of the peer-reviewed published literature. Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia), 24(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2015.08.001

- Janssen, I., Hanssen, M., Bak, M., Bijl, R. V., de Graaf, R., Vollebergh, W., McKenzie, K., & van Os, J. (2003). Discrimination and delusional ideation. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 182(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.1.71

- Karidi, M., Vassilopoulou, D., Savvidou, E., Vitoratou, S., Maillis, A., Rabavilas, A., & Stefanis, C. (2015). Bipolar disorder and self-stigma: A comparison with schizophrenia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.038

- Koschorke, M., Padmavati, R., Kumar, S., Cohen, A., Weiss, H. A., Chatterjee, S., Pereira, J., Naik, S., John, S., Dabholkar, H., Balaji, M., Chavan, A., Varghese, M., Thara, R., Thornicroft, G., & Patel, V. (2014). Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 123, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035

- Kothari, S. (2007). Prognosis and outcome. In Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice (pp. 186). Demos Medical Publishing.

- Krendl, A., & Pescosolido, B. (2020). Countries and cultural differences in the stigma of mental illness: The East–West divide. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 51(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022119901297

- Landeen, J., Seeman, M., Goering, P., & Streiner, D. (2007). Schizophrenia: Effect of perceived stigma on two dimensions of recovery. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 1(1), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.3371/CSRP.1.1.5

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Boutillier, C. L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 199(6), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Li, L., Rami, F. Z., Lee, B. M., Kim, W.-S., Kim, S.-W., Lee, B. J., Yu, J.-C., Lee, K. Y., Won, S.-H., Lee, S.-H., Kim, S.-H., Kang, S. H., Kim, E., & Chung, Y.-C. (2022). Three-year outcomes and predictors for full recovery in patients with early-stage psychosis. Schizophrenia, 8(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-022-00301-4

- Lien, Y.-J., Chang, H.-A., Kao, Y.-C., Tzeng, N.-S., Lu, C.-W., & Loh, C.-H. (2017). The impact of cognitive insight, self-stigma, and medication compliance on the quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 268(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-017-0829-3

- Link, B., & Phelan, J. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Luo, H., Li, Y., Yang, B. X., Chen, J., & Zhao, P. (2022). Psychological interventions for personal stigma of patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 148, 348–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.02.010

- Luo, Y., Zhang, L., He, P., Pang, L., Guo, C., & Zheng, X. (2019). Individual-level and area-level socioeconomic status (SES) and schizophrenia: Cross-sectional analyses using the evidence from 1.9 million Chinese adults. BMJ Open, 9(9), e026532. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026532

- Lysaker, P., Roe, D., & Yanos, P. (2006). Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(1), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbl016

- Lysaker, P., Roe, D., Ringer, J., Gilmore, E., & Yanos, P. (2012). Change in self-stigma among persons with schizophrenia enrolled in rehabilitation: Associations with self-esteem and positive and emotional discomfort symptoms. Psychological Services, 9(3), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027740

- Macinnes, D. L. (2006). Self-esteem and self-acceptance: An examination into their relationship and their effect on Psychological Health. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 13(5), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00959.x

- Magallares, A., Perez-Garin, D., & Molero, F. (2016). Social stigma and well-being in a sample of schizophrenia patients. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 10(1), 51–57. https://doi.org/10.3371/csrp.mape.043013

- Maharjan, S., & Panthee, B. (2019). Prevalence of self-stigma and its association with self- esteem among psychiatric patients in a Nepalese teaching hospital: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 347. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2344-8

- Mäkinen, J., Miettunen, J., Isohanni, M., & Koponen, H. (2008). Negative symptoms in schizophrenia—A review. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 62(5), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480801959307

- Mancini, M. A. (2007). The role of self–efficacy in recovery from serious psychiatric disabilities: A qualitative study with fifteen psychiatric survivors. Qualitative Social Work, 6(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325007074166

- Mansour, H., Mueller, C., Davis, K. A., Burton, A., Shetty, H., Hotopf, M., Osborn, D., Stewart, R., & Sommerlad, A. (2020). Severe mental illness diagnosis in English general hospitals 2006-2017: A registry linkage study. PLoS Medicine, 17(9), e1003306. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003306

- Marcussen, K., Gallagher, M., & Ritter, C. (2021). Stigma resistance and well-being in the context of the mental illness identity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 62(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146520976624

- McCutcheon, R. A., Abi-Dargham, A., & Howes, O. D. (2019). Schizophrenia, dopamine and the striatum: From biology to symptoms. Trends in Neurosciences, 42(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2018.12.004

- McCutcheon, R. A., Reis Marques, T., & Howes, O. D. (2020). Schizophrenia—An overview. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3360

- McDaid, D., Park, A.-L., Davidson, G., John, A., Knifton, L., McDaid, S., Morton, A., Thorpe, L., & Wilson, N. (2022). The economic case for investing in the prevention of mental health conditions in the UK. Mental Health Foundation.

- Memon, A., Taylor, K., Mohebati, L., Sundin, J., Cooper, M., Scanlon, T., & de Visser, R. (2016). Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: A qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open, 6(11), e012337. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

- Mittal, D., Sullivan, G., Chekuri, L., Allee, E., & Corrigan, P. W. (2012). Empirical studies of self-stigma reduction strategies: A critical review of the literature. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 63(10), 974–981. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100459

- Morrison, A. P., Burke, E., Murphy, E., Pyle, M., Bowe, S., Varese, F., Dunn, G., Chapman, N., Hutton, P., Welford, M., & Wood, L. J. (2016). Cognitive therapy for internalised stigma in people experiencing psychosis: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 240, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.024

- Mueser, K. T., DeTore, N. R., Kredlow, M. A., Bourgeois, M. L., Penn, D. L., & Hintz, K. (2020). Clinical and demographic correlates of stigma in first‐episode psychosis: The impact of duration of untreated psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13102

- O'Connor, L., Yanos, P., & Firmin, R. (2018). Correlates and moderators of stigma resistance among people with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 270, 198–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.09.040

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. (2021). Ethnicity spotlight. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-spotlights/ethnicity-covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. (2021). Ethnicity spotlight. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-spotlights/ethnicity-covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-s urveillance-report

- Pescosolido, B., Manago, B., & Monahan, J. (2019). Evolving public views on the likelihood of violence from people with mental illness: Stigma and its consequences. Health Affairs, 38(10), 1735–1743. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00702

- Picco, L., Pang, S., Lau, Y. W., Jeyagurunathan, A., Satghare, P., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J. A., Lim, S., Poh, C. L., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2016). Internalized stigma among psychiatric outpatients: Associations with quality of life, functioning, hope and self-esteem. Psychiatry Research, 246, 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.041

- Pitt, L., Kilbride, M., Welford, M., Nothard, S., & Morrison, A. P. (2009). Impact of a diagnosis of psychosis: User-led qualitative study. Psychiatric Bulletin, 33(11), 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.108.022863

- PSHE Association. (2023). Mental health. PSHE Association. https://pshe-association.org.uk/topics/mental-health

- Pyle, M., & Morrison, A. P. (2013). “It’s just a very taboo and secretive kind of thing”: Making sense of living with stigma and discrimination from accounts of people with psychosis. Psychosis, 6(3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2013.834458

- Radua, J., Ramella-Cravaro, V., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Reichenberg, A., Phiphopthatsanee, N., Amir, T., Yenn Thoo, H., Oliver, D., Davies, C., Morgan, C., McGuire, P., Murray, R. M., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2018). What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of risk and protective factors. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 17(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20490

- Rawlett, K. (2014). Journey from self-efficacy to empowerment. Health Care, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.12966/hc.02.01.2014

- Recovery in the Bin. (2016). Unrecovery star. Recovery in the Bin. https://recoveryinthebin.org/unrecovery-star-2/

- Reneses, B., Sevilla Llewellyn-Jones, J., Vila-Badia, R., Palomo, T., Lopez-Micó, C., Pereira, M., José Regatero, M., Ochoa., & S., Retrieved. (2020). The relationships between sociodemographic, psychosocial and clinical variables with personal-stigma in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Actas Espanolas de Psiquiatria, 48(3), 116–125. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32905604/

- Ritsher, J., Otilingam, P. G., & Grajales, M. (2003). Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research, 121(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008

- Rose, D., Willis, R., Brohan, E., Sartorius, N., Villares, C., Wahlbeck, K., & Thornicroft, G, INDIGO Study Group. (2011). Reported stigma and discrimination by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 20(2), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796011000254

- Sari, S. P., Agustin, M., Wijayanti, D. Y., Sarjana, W., Afrikhah, U., & Choe, K. (2021). Mediating effect of hope on the relationship between depression and recovery in persons with schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 627588. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.627588

- Sarraf, L., Lepage, M., & Sauvé, G. (2022). The clinical and psychosocial correlates of self-stigma among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders across cultures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 248, 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2022.08.001

- Schwarzbold, M., Kern, R., Novacek, D., McGovern, J., Catalano, L., & Green, M. (2021). Self-stigma in psychotic disorders: Clinical, cognitive, and functional correlates in a diverse sample. Schizophrenia Research, 228, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.12.003

- Shrivastava, A., Bureau, Y., & Johnston, M. (2012). Stigma of mental illness-1: Clinical reflections. Mens Sana Monographs, 10(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.90181

- Silver, K. (2017). ‘Depression lost me my job’: How mental health costs up to 300,000 jobs a year. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-41740666

- Skierkowski, D. D., Florin, P., Harlow, L. L., Machan, J., & Ye, Y. (2019). A readability analysis of online mental health resources. The American Psychologist, 74(4), 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000324

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of medical research council guidance. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Stewart, H. (2020). Optimism, hope and the power of positive thinking. https://www.hospiscare.co.uk/optimism-hope-and-the-power-of-positive-thinking/

- Stickley, A., Oh, H., Sumiyoshi, T., Narita, Z., DeVylder, J. E., Jacob, L., Waldman, K., & Koyanagi, A. (2019). Perceived discrimination and psychotic experiences in the English general population. European Psychiatry, 62, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.08.004

- Stilo, S. A., & Murray, R. M. (2019). Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(10), 100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3

- Thoits, P. (2011). Resisting the stigma of mental illness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74(1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272511398019

- Thornicroft, G., Bakolis, I., Evans‐Lacko, S., Gronholm, P. C., Henderson, C., Kohrt, B. A., Koschorke, M., Milenova, M., Semrau, M., Votruba, N., & Sartorius, N. (2019). Key lessons learned from the Indigo Global Network on Mental Health Related Stigma and discrimination. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(2), 229–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20628

- Thornicroft, G., Brohan, E., Rose, D., Sartorius, N., & Leese, M, INDIGO Study Group. (2009). Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet, 373(9661), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61817-6

- Thornicroft, G., Sunkel, C., Alikhon Aliev, A., Baker, S., Brohan, E., el Chammay, R., Davies, K., Demissie, M., Duncan, J., Fekadu, W., Gronholm, P. C., Guerrero, Z., Gurung, D., Habtamu, K., Hanlon, C., Heim, E., Henderson, C., Hijazi, Z., Hoffman, C., … Winkler, P. (2022). The Lancet Commission on ending stigma and discrimination in Mental Health. The Lancet, 400(10361), 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01470-2

- Tsiachristas, A., Thomas, T., Leal, J., & Lennox, B. R. (2016). Economic impact of early intervention in psychosis services: Results from a longitudinal retrospective controlled study in England. BMJ Open, 6(10), e012611. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012611

- Valery, K.-M., & Prouteau, A. (2022). Schizophrenia stigma in mental health professionals and associated factors: A systematic review. European Psychiatry, 65(S1), S617–S617. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1580

- van der Ven, E., & Selten, J.-P. (2018). Migrant and ethnic minority status as risk indicators for schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(3), 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000405

- Van Eck, R. M., Burger, T. J., Vellinga, A., Schirmbeck, F., & de Haan, L. (2017). The relationship between clinical and personal recovery in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(3), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx088

- Vass, V., Morrison, A. P., Law, H., Dudley, J., Taylor, P., Bennett, K. M., & Bentall, R. P. (2015). How stigma impacts on people with psychosis: The mediating effect of self-esteem and hopelessness on subjective recovery and psychotic experiences. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.042

- Vass, V., Sitko, K., West, S., & Bentall, R. P. (2017). How stigma gets under the skin: The role of stigma, self-stigma and self-esteem in subjective recovery from psychosis. Psychosis, 9(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2017.1300184

- Vauth, R., Kleim, B., Wirtz, M., & Corrigan, P. W. (2007). Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 150(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005

- Vogel, J. S., Bruins, J., de Jong, S., Knegtering, H., Bartels-Velthuis, A. A., Bruggeman, R., Jörg, F., Pijnenborg, M. G. H. M., Veling, W., Visser, E., van der Gaag, M., … & Castelein, S, PHAMOUS Investigators. (2021). Satisfaction with social connectedness as a predictor for positive and negative symptoms of psychosis: A PHAMOUS study. Schizophrenia Research, 238, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2021.10.004

- Vrbova, K., Prasko, J., Ociskova, M., Kamaradova, D., Marackova, M., Holubova, M., Grambal, A., Slepecky, M., & Latalova, K. (2017). Quality of life, self-stigma, and hope in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 567–576. volume https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s122483

- Waite, F., Knight, M. T., & Lee, D. (2015). Self-compassion and self-criticism in recovery in psychosis: An interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(12), 1201–1217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22211

- Winsper, C., Crawford-Docherty, A., Weich, S., Fenton, S.-J., & Singh, S. P. (2020). How do recovery-oriented interventions contribute to personal mental health recovery? A systematic review and Logic Model. Clinical Psychology Review, 76, 101815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101815

- Wood, L., & Irons, C. (2017). Experienced stigma and its impacts in psychosis: The role of social rank and external shame. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 90(3), 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12127

- Wood, L., Birtel, M., Alsawy, S., Pyle, M., & Morrison, A. (2014). Public perceptions of stigma towards people with schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 604–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.012

- Wood, L., Byrne, R., Burke, E., Enache, G., & Morrison, A. P. (2017). The impact of stigma on emotional distress and recovery from psychosis: The mediatory role of internalised shame and self-esteem. Psychiatry Research, 255, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.016

- Wood, L., Byrne, R., Enache, G., Lewis, S., Fernández Díaz, M., & Morrison, A. P. (2022). Understanding the stigma of psychosis in ethnic minority groups: A qualitative exploration. Stigma and Health, 7(1), 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000353

- Wood, L., Byrne, R., Varese, F., & Morrison, A. P. (2016). Psychosocial interventions for internalised stigma in people with a schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis: A systematic narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research, 176(2-3), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.001

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. The Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.2307/258173

- World Health Organization. (2010). User empowerment in mental health: A statement by the WHO Regional Office for Europe - Empowerment is not a destination, but a journey. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107275

- World Health Organization. (2019). 6A20 schizophrenia. In ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th ed.). World Health Organization. https://icd.who.int/1683919430

- Yang, L. H., Chen, F.-P., Sia, K. J., Lam, J., Lam, K., Ngo, H., Lee, S., Kleinman, A., & Good, B. (2014). “What matters most:” A cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 103, 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.009

- Yanos, P. T., DeLuca, J. S., Roe, D., & Lysaker, P. H. (2020). The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112950

- Yanos, P., Roe, D., & Lysaker, P. (2010). The impact of illness identity on recovery from severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 13(2), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487761003756860

- Yılmaz, E., & Okanlı, A. (2015). The effect of internalized stigma on the adherence to treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(5), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2015.05.006

- Yu, B. C. L., Chio, F. H. N., Mak, W. W. S., Corrigan, P. W., & Chan, K. K. Y. (2021). Internalization process of stigma of people with mental illness across cultures: A meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102029

Appendix A

Appendix B

Table B1. Study characteristics.