ABSTRACT

The label “crack user” is profoundly stigmatizing. Such labels are foundational to an individual’s identity, affecting how others view them, their self-perceptions, and subsequent behavior. Individuals can also resist labels such as “crack user,” creating distinctions for the same behavior. To elucidate characteristics associated with self-application of stigmatizing labels, we use data from individuals (N = 50,721) serviced for smoking cocaine in French drug treatment centers (N = 263) from 2010–2020 to assess who self-labels their behavior “crack use” or does not in favor of “smoked cocaine,” which are identical behaviors. Multilevel models reveal higher odds of using the less stigmatizing “smoked cocaine” in earlier years, among those with less risky cocaine use profiles, and among those not using other stimulants. Importantly, this less stigmatizing label is more common among those of high SES and outside the Paris region. An interaction demonstrates that even within Paris, those of high SES have higher odds of using this label than their lower SES Parisian counterparts. Those in privileged positions may use this alternative label to avoid stigmatization of the “crack user” label. Such distinctions potentially perpetuate inequalities associated with the more stigmatized label. We suggest that treatment centers can act as sites to combat these differences.

Introduction

The use of crack cocaine, the combination of hydrochloride (powder) cocaine with water and sodium bicarbonate or ammonia (baking soda), is a highly stigmatized behavior (Reinarman and Levine Citation2004). Some of this stigmatization follows from the risk associated with its use, as it is known to be related to serious health comorbidities. Negative physical outcomes include lung and respiratory damage and consequent infection (Restrepo et al. Citation2007; Story, Bothamley, and Hayward Citation2008), the transmission of hepatitis C and other blood-borne diseases, and facilitation of the transmission of HIV through risky sexual behaviors (Prangnell et al. Citation2017). The chronic use of crack cocaine is associated with serious cognitive disfunctions such as deficient verbal memory and attention deficits (De Oliveira et al. Citation2009). Negative psychosocial outcomes include depression, posttraumatic stress disorder and antisocial personality disorder (Falck et al. Citation2004), disruption to vital bodily functions, poor social functioning, and poor overall mental health (Falck et al. Citation2000). Similar to other illicit substances, these negative outcomes are magnified by the adverse conditions in which many people who use crack cocaine live (Escobar et al. Citation2018). However, many other effects have been considerably exaggerated (Reinarman and Levine Citation2004). Regardless of the truth behind particular claims about the substance, this stigmatization of the behavior resulted in a fear of being labeled a crack user, which subsequently may have been associated with some of the declines in crack use experienced after the 1980s and 1990s (Furst et al. Citation1999).

However, evidence suggests that the availability of crack cocaine has recently increased in several Western European countries (EMCDDA Citation2019). Crack cocaine has been noted in treatment centers in major cities in the Netherlands (Pérez et al. Citation2013), and has shown significantly increasing prevalence rates in England (Hay et al. Citation2019) and France (Janssen et al. Citation2021). The question arises as to how such a stigmatized activity could make a resurgence. In this article, we use data from France to consider the role of stigma and labels regarding crack cocaine use, how such use could be redefined as less stigmatizing through alternative labeling, and which individuals take advantage of alternative labeling and what that could imply for inequality.

The importance of labels

The importance and consequences of labels is foundational to social psychology. Individuals’ sense of self is a product of repeated social interactions, constructed from comparisons between oneself and others, the reflected appraisals of others, and one’s self-appraisals (Blumer Citation1969; Mead Citation1934). This process has been particularly applied among studies of deviance within the labeling theory tradition (Becker Citation1963; Lemert Citation1951). In short, through others’ continual enforcement of a deviant label, such as drug user, individuals come to view themselves as such a deviant and the associated stereotypes as true of themselves, incorporating it into their self-conception (Heimer and Matsueda Citation1994; Matsueda Citation1992). As a result, they become more deeply enmeshed within the activities associated with that label. Notably, stigmatized individuals can learn to combat the label, even attempting to redefine it less negatively (Kitsuse Citation1980; Thoits Citation2011). The move toward person-first language in addiction research and beyond is partially intended to reduce stigma (Kelly and Westerhoff Citation2010; McGinty and Barry Citation2020). In what follows, we note that we use terms such as “drug user” and “crack user” when required to emphasize their stigmatizing nature as a label, but use person-first language otherwise.

Research shows that the term “crack user” (or “crackhead” in English-speaking countries or “cracker” in France) is a very stigmatizing label. Stigmatized labels are typically subject to stereotyping that results in internalization of the associated stigmatized identity; the crack user label comes with a host of such stereotypes such as addictive personality, tendency for crime and violence, being a poor parent, and poor hygiene (Reinarman and Levine Citation2004). Negative labels among people who use drugs, including those such as crackhead, junkie, dope fiend, pothead, or tweaker, are known as a site of identity work (Boeri Citation2004; Copes Citation2016; Copes, Hochstetler, and Patrick Williams Citation2008; Draus, Roddy, and Greenwald Citation2010; Rødner Citation2005; Sandberg Citation2012). People who use drugs may actively resist these labels and the associated identity, drawing distinctions among their own use and that of others to avoid these labels. The social psychological mechanism for making these distinctions is a process known as defensive othering (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000; Snow and Anderson Citation1987). For those who smoke cocaine, a desire for a label that does not imply “crack user” or “crackhead” is one such example. This identity work extends beyond people who use drugs; the shame of being labeled a crackhead was so stigmatizing in neighborhoods with high use that young people took pride in not using cocaine, potentially protecting cohorts coming of age after the rise in crack cocaine use (Furst et al. Citation1999).

Importantly, these labels are not applied evenly by socioeconomic and demographic categories in society. In countries such as the U.S., media depictions specifically of the crack form of cocaine described the drug in hyperbolic negative terms that emphasized the need for a strong criminal justice response and explicitly linked such depictions to Black Americans (Reinarman and Levine Citation2004), a stark difference from the later opioid crisis that focused on a health response and White Americans (Lindsay and Vuolo Citation2021). These depictions and demographic associations drove policies that enshrined massive disproportionalities in sentencing relative to powder cocaine that was typically used by middle- and upper-class White Americans (Alexander Citation2012; Beckett Citation1997). These racialized and class-based negative perceptions of crack cocaine persist to the present (Lindsay and Vuolo Citation2021).

While race is likely a salient factor in France, the legal prohibition on collecting data regarding race (a point to which we return in the discussion) results in proxy terminology to make demographic distinctions (Goulian et al. Citation2022). As Goulian et al. describe, “As a consequence of a color-blindness discourse, the French framing of people who use crack cocaine is primarily viewed through a social class lens” (Goulian et al. Citation2022: 3). Through this lens, use of crack cocaine has long been associated with those living in extremely adverse conditions, and mostly within Paris (Gérome et al. Citation2018). However, in recent years precisely as changes in labeling began to occur, ethnographic studies have underscored the increasing visibility of people who use drugs who are more integrated into social institutions, describing employment and stable housing, away from the traditional Parisian market and reflecting a geographic diffusion (Gérome et al. Citation2018), conclusions supported by quantitative findings as well (Janssen et al. Citation2021). In France then, class and geography are potentially salient factors for understanding labeling. Thus, consideration of distinctions in who applies what labels to themselves is important for understanding not only labeling, but issues of inequality.

What to call the act of smoking cocaine

Prior studies have highlighted the concurrent use of a number of alternative labels for crack cocaine use, such as “freebase,” “based cocaine,” or “smoking cocaine” – the former of which has fallen out of use, whereas the latter two labels have persisted (Janssen et al. Citation2021). This distinction has made its way into professional settings in France, as some individuals who use the drug did not recognize smoking cocaine as crack cocaine use. To reflect this labeling difference, health professionals have increasingly adopted both labels when interviewing clients in treatment or attending to people who use drugs in harm reduction facilities. However, this distinction is merely a label for the same activity. To smoke cocaine, powder cocaine (or cocaine hydrochloride) must be converted to base form, which is crack cocaine. Whether an individual purchases powder and converts it on their own or purchases already converted crack cocaine, the substance is the same (Hatsukami and Fischman Citation1996). From the perspective of the person using cocaine, however, “crack” and “smoking cocaine” can refer to completely different substances and practices.

As with the resurgence of crack cocaine in Europe noted above, other substances have exhibited similar increases when labels, form of the substance, and route of administration evolve. Despite MDMA and ecstasy being the same substance, the former is now considered to have better effects, be safer, and as more in fashion (Edland-Gryt, Sandberg, and Pedersen Citation2017; Girard and Bosher Citation2010). Edland-Gryt et al. (Citation2017) propose that use of MDMA/ecstasy reemerged due to shifts in both route of administration from pill to powder form, as well as a label shift from ecstasy to MDMA. Similarly, the first wave of substantial increases in opioid use in the U.S. during the 21st century has largely been attributed to pharmaceutical opioids (Ciccarone Citation2021), which were viewed among some who used this substance as a less risky and stigmatized form of the substance given its medical origin (Daniulaityte, Falck, and Carlson Citation2012). Even as the opioid crisis shifted to heroin (Ciccarone Citation2021), characterizations of people who use opioids continued to stress destigmatization of addiction and preventing application of the “addict” label, a stark contrast from the wave of heroin use in the 1980s (Lindsay and Vuolo Citation2021). Finally, historic lows in nicotine use in the form of tobacco cigarettes have been achieved in many countries using stigmatization of “smokers” as a public health tool (Bayer and Stuber Citation2006; Bell et al. Citation2010; Stuber, Galea, and Link Citation2008). The advent of electronic cigarettes as a perceived less risky and stigmatized form of use, however, has led to such a resurgence in nicotine use as to be labeled an “epidemic” among youth by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Glantz and Bareham Citation2018).

While these examples are informative, similar differences do not exist for crack cocaine versus smoking cocaine, however, as they are indeed the same. One hypothesis states that the use of alternative labels may be a way to overcome the stigma associated with the term “crack” (Janssen et al. Citation2020). Thus, the consequences of these distinctions are unlikely to be only semantic, as labels matter for individuals.

Current study

To our knowledge, prior studies have only considered crack cocaine use writ large, merging “crack cocaine users” and self-defined “cocaine smokers” as a whole. This approach is understandable given that they are the same activity. However, which labels individuals apply to themselves may be consequential. But to date, very little is known about labeling practices among varying sub-populations and what this might imply for social inequality. The question that arises is: are we truly dealing with the same people who use this substance, or is it that the label “crack cocaine users” encompasses a more heterogenous population than once thought (Janssen et al. Citation2020)? To answer this question, we use multilevel models of inpatients across treatment centers in France who indicated they used crack cocaine. We examine who is more likely to use the label “crack” relative to eschewing that terminology in favor of the label “smoking cocaine.” In doing so, we not only underscore the differing profiles of those who use each label, but also uncover how those in particular positions of privilege are more likely to use the latter.

Methods

Data

The data come from a yearly updated compendium on addictions and treatments (Recueil commun sur les addictions et les prises en charge - RECAP), carried out at the national level in France (Palle Citation2021). Following the European protocol for registering treatment demand, one of the key indicators of the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), all treatment centers are requested to provide data on clients welcomed into their premises during a full calendar year. Treatment centers in France are publicly funded, medically-focused entities located within each of the sub-regional administrative areas. They provide free, anonymous access to all individuals seeking treatment for addiction, both to licit and illicit substances, regardless of their demographic and socioeconomic background, and aim for complete cessation of substance use. Treatment centers provide outpatient (including in-prison) and inpatient services. Both medication-assisted treatments, such as methadone maintenance and buprenorphine prescription, and psychosocial treatment are provided. Due to its annual frequency, the number of individuals included in RECAP is fairly high (more than 205,000 clients in 2020) and provides the ability to analyze certain sub-groups of clients, in this case people who use crack cocaine.

The face-to-face, standardized questionnaire includes information on individual substance use, health, and sociodemographic characteristics. Questions on substances refer to past 30-day use and include name of the substance(s), frequency of use, and route of administration, as well as a clinical assessment of the severity of use. In order to provide an accurate description of these individuals, the standardized questionnaire accounts for several questions on sociodemographics, including gender, age, schooling, housing, job status, main financial resources, type of occupation, and socioeconomic status (SES). The survey was approved by the Scientific Committee of the French Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (Observatoire français des drogues et des tendances addictives, OFDT) and the National Data Protection Authority (CNIL).

Dependent variable

The dependent variable consists of the labels used by people who use crack cocaine to self-define their use during the past 30 days. There are three possibilities. First, among the choices for which substances they used, respondents may check “crack cocaine,” which we classify as the label “used crack.” Second, for the same question, they may check “powder cocaine.” However, in a follow-up question for each substance used concerning route of administration, some respondents who indicate powder cocaine use then go on to check that “smoked” was the route of administration. We classify such respondents as labeling themselves as “smoked cocaine.” Finally, individuals can check both, which we maintain as a separate category. As emphasized above, the labels “used crack” and “smoked cocaine” as constructed quantitatively are used regularly within treatment settings based on the label preference of patients who use cocaine.

Independent variables

At the individual level, the models account for year of survey, gender (male as reference), age (15–24 as reference, 25–34, and 35–64), and SES based on the occupation reported by the clients and coded applying the typology of the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies. The original variable was recoded in a 3-category variable: low SES (inactive, unemployed); intermediate SES (farmers; self-employed, intermediate occupations, technicians; white collar workers); high SES (managers, professors, liberal or intellectual professions). Substance-related questions include age at onset (prior to age 20 vs 20 or older as reference), the severity of use assessed by a health professional on a 3-level scale (low as reference, medium, high), last month use of opioids, last month use of stimulants and last month use of hallucinogens, last month injecting drugs (no as reference in all cases). At the treatment center level, the model also accounts for the type of center (ambulatory as reference as reference vs other type of facility) and the geographic location of the facilities (Paris metropolitan region as reference vs other regions). The population study was restricted to individuals aged 15 to 64 years old.

Statistical analysis

Given the hierarchical structure of the data, in which patients are nested in treatment centers, we conducted multilevel multinomial logistic regression (Hedeker Citation2003) using Stata® 16.1’s gsem command with robust standard errors. In our models, there are 50,721 patients and 263 treatment centers. We first display a model with main effects only. Then, given our hypothesized importance of class and geography, we show a second model with an interaction between these two measures. To aid interpretation, we show predicted probabilities for these two measures, obtained via the margins command in Stata.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The characteristics of the sample are shown in . For the labeling of their cocaine smoking behavior, 43.6% said “used crack,” 53.9% said “smoked cocaine,” and 2.4% said both. The low percentage who stated both likely indicates that most patients who use cocaine in this manner have a clear preference for a label. Regarding the overall temporal trend, there is a considerable increase in the number of inpatients using crack cocaine and treatment centers reporting attendance of such individuals in France over the past decade, more than doubling from 2010 to 2020. We note that the Covid-induced lockdowns in 2020 (April-May and October-November) did not affect attendance: treatment centers managed to maintain contact with their patients, in particular through online consulting and hotlines. Overall, people serviced in treatment centers who use crack cocaine are mostly males (78.4%), aged 35 or older (66.3%), and have low SES (69.9%). They partake in polysubstance use, with a predilection for other stimulants. Their severity of use is most often assessed as high. They are more commonly serviced in ambulatory facilities (76.6%). While most are located in provinces at 69.1%, this number is disproportionate to the 80.0% of the population that lives in the provinces relative to the Paris region. That is, the Paris region is overrepresented among crack cocaine treatment patients relative to its proportion of the population of France.

Table 1. Characteristics of people who use crack cocaine serviced in treatment centers, France, 2010–2020 (N and row percentages).

We now consider the use of the labels by these characteristics. Across years, using both labels decreased over time; the proportion was 4.3% in 2010 and 1.9% in 2020. Use of the label “crack cocaine” increased from 2010 (41.6%) to 2012 (47.1%) before decreasing through 2016 (38.9%), only to consistently increase through 2020 (45.9%); the use of “smoked cocaine” of course is a near mirror image. While the labels used by males and females are strikingly similar, there are notable differences across most other individual-level variables. The “used crack” label was more common among those aged 25–64 (50.2%), of low SES (45.8%), who used other stimulants (66.8%), who injected drugs (57.6%), who had earlier age of onset (52.3%), and with a high severity profile (51.1%). On the other hand, the “smoked cocaine” label was more common among those aged 15–24 (64.9%) and 25–34 (63.8%), those of intermediate (58.7%) and high (59.1%) SES, who used opioids (58.0%), who used hallucinogens (61.4%), with older age of onset (67.8%), and with low (61.6%) and medium (61.1%) severity profiles. Regarding treatment center measures, the “smoked cocaine” label is more common in ambulatory facilities (60.6%), but the percentages in the other types of facilities is close to the marginal percentages. The label is highly region-dependent: “using crack” is most commonly referred to among those in the Paris metropolitan region (77.6%), whereas “smoked cocaine” is more often referred to in the provinces (71.1%).

Multilevel Models

The results of the multivariate analysis are shown in . Model 1 includes the main effects only. Controlling for the other variables, the label is unrelated to gender, nor is it associated with the type of treatment center. The use of the “smoking cocaine” label has been mostly decreasing over the years (relative to 2020: OR = 1.74, p < .001 in 2010; OR = 1.65, p < .001 in 2015; OR = 1.15, p < .01 in 2019), confirming the descriptive results. A similar trend persists regarding the use of both labels (OR = 2.86, p < .001; OR = 1.43; p < .05, OR = 1.25, p > .05, respectively). Compared to labeling “use crack,” the coefficients for age show that, relative to those aged 15–24, the associated odds of labeling “smoked cocaine” are 17% higher for those aged 25–34 and the odds of using both labels are 48% higher for those aged 35–64. The label is strongly related to SES (LR test = 174.14, p < 0.0001): the higher the SES, the higher the tendency to refer to “smoking cocaine” instead of “using crack,” with odds 31% higher for intermediate SES (p < .001) and nearly 3 times higher for those of high SES (p < .001) relative to low SES. Compared to low SES, only those of the highest SES are more likely to use both labels (OR = 2.08, p < .05), a notable result given the reduced number of people in these categories. Self-labeling “smoking cocaine” is more common among those who use opioids (OR = 1.17, p < .001) and hallucinogens (OR = 1.33, p < .001) – that is, they more likely to partake in polysubstance use – and less common among those using other stimulants (OR = 0.20, p < .001) or who inject drugs (OR = 0.66, p < .001). Younger age at onset is associated with 85% higher odds of using the label “smoking cocaine” (p < .001). Lastly among the patient-level factors, the associated odds of the smoking cocaine label are lower for measures of the severity of use, with 18% lower odds for medium severity (p < .001) and 53% lower odds for high severity (p < .001) relative to low severity. A reversed trend shows for the use of both labels (OR = 1.97, p < .001 and OR = 2.60, p < .001, respectively).

Table 2. Factors associated with the use of a specific label to acknowledge past month crack cocaine use among those serviced in treatment centers, France, 2010–2020.

The geographic effect is also significant, unequivocally improving the fit of the model (LR test = 173.53, p < .0001). Relative to “use crack,” the odds of people located in the Paris region to state they smoked cocaine are 90% lower than other parts of France, a considerably large negative effect (p < .001). Stated reversely, the odds of using the label “use crack” are 10 times higher in Paris compared to saying “smoked cocaine.” A supplementary analysis splitting the provinces into more detailed regions showed no significant contrasts, illustrating an overall opposition between the Paris metropolitan region and the other regions. Part of this geographic effect is pictured by the median odds-ratio (MOR), that “translates the higher-level variance in the odds ratio scale” (Merlo et al. Citation2006: 292) to show the extent to which the individual probability varies across clusters. In all cases, the MOR is greater than 2.0 with 95% Confidence Limits that exclude the value 1, denoting significant between-cluster variance. The random effect reflects significantly different averages in labeling across treatment centers and concomitantly high within-cluster homogeneity.

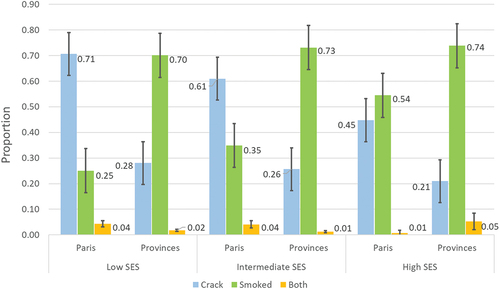

In order to better assess the influence of SES and region, we ran a second model including an interaction, with results that show the importance of labeling (LR test = 109.58, p < .0001). For ease of interpretation, we show the interaction effect as predicted probabilities in , with other variables held constant at their respective means. The overwhelming preference to use the label “smoked cocaine” in the provinces appears to be relatively consistent across SES. Across SES from low to high, the proportion who used “smoked cocaine” ranges from 0.70 to 0.74, while the percentage who referred to “used crack” ranges from 0.28 to 0.21. While there is increasing tendency to use “smoke cocaine” and decreasing tendency to use “used crack,” these differences are slight and not statistically significant, as shown by the confidence intervals. However, the interaction effect becomes apparent when examining labels among those in the Paris region. The differences across SES are larger and, in most cases, statistically significant. The proportion reporting “use crack” decreases from 0.71 for low SES Paris region residents to 0.61 for intermediate SES to 0.45 for high SES. Conversely, the proportion reporting “smoked cocaine” increases from 0.25 for low SES to 0.35 for intermediate SES to 0.54 for high SES. For high SES Paris region residents, the proportion reporting either label is no longer statistically significant. This interaction effect demonstrates that even in Paris where the crack label is more common, high SES individuals are disproportionately unlikely to use this label relative to their lower SES Parisian counterparts.

Discussion

Classic and contemporary theorizing within social psychology and studies of deviance emphasize the importance of labels for how individuals view one another, how they view themselves, and how they subsequently behave (Becker Citation1963; Blumer Citation1969; Heimer and Matsueda Citation1994; Lemert Citation1951; Matsueda Citation1992; Mead Citation1934). However, within-group labeling distinctions are also important because they separate individuals conducting the same behavior into different groups. When those groups are patterned by particular social characteristics, they have the potential to create, perpetuate, or exacerbate inequality by associating those in lower socioeconomic positions with more stigmatizing labels. In this article, we considered the self-application of the highly stigmatized label of being a “crack cocaine user” (Reinarman and Levine Citation2004) and contrasted it with those who smoked cocaine without labeling it “crack cocaine use.” To assess these differences, we took advantage of a nationwide, standardized, annual survey among treatment centers in France to assess the use of different labels to refer to past 30-day crack cocaine use over the last decade. Using multilevel regressions to account for the hierarchical structure of the data (patients nested into treatment centers), we uncovered important distinctions in who self-identifies using each label, including results that illuminate how certain characteristics are associated with the particularly stigmatizing crack label. Here, we discuss the implications of these findings.

In our models, we found many distinguishing factors in terms of who self-applies the labels “crack use” versus “smoked cocaine.” Somewhat surprisingly, very few individuals used both labels, such that a near dichotomy exists in terms of labeling and with a roughly even split in the two labels among treatment patients. As described, these differences can result from individuals attempting to make distinctions between themselves and the “bad” people who use the same drug (Boeri Citation2004; Copes Citation2016; Cope et al. Citation2008; Draus et al. Citation2010; Rødner Citation2005; Sandberg Citation2012) in a process known as defensive othering (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000; Snow and Anderson Citation1987). This process of identity work is important to maintaining an image of oneself that does not incorporate the negative aspects of the stigmatized identity. If others do not see a person as possessing a particular stigmatized identity, the individual will not either, thus protecting both how others see them and how they see themselves.

While this process can be used to combat the label effectively and potentially redefine it (Kitsuse Citation1980; Thoits Citation2011), it could also create boundaries around the use of the label by specific groups of people. For example, those with higher risk profiles (as assessed by treatment center health professionals) were less likely to self-label as a “crack user,” which could be a conscious or unconscious attempt to make a distinction between their less risky crack use and “true” crack use. Similarly, those who use opioids and hallucinogens were less likely to use the crack label, possibly seeing themselves as someone who uses another drug class and unwilling to commit to the more stigmatizing crack label, unlike those who use other stimulants than cocaine who were more likely to use the crack label. Notably, gender was not a defining characteristic in terms of labeling.

Where inequality became most apparent in the self-labeling process was in the particularly strong effects of SES and geographic location. Regarding the main effects of the latter, there was a clear opposition between people who use crack cocaine attending treatment in the Paris province compared to those in other regions, with living in Paris associated with 10 times higher odds of using the label “crack user.” This effect shows a strong tendency for non-Parisians to choose a label that they may associate with the drug scene in the country’s largest and most diverse urban area. This finding is an important distinction within France given the diffusion of crack cocaine, first located in Paris during the 1980s among the most under-privileged before spreading at the end of the 2000s toward new markets. Moreover, the increasing heterogeneity of people who use crack cocaine in France is not only a mere effect of the diffusion across the territory. It also reflects in-depth changes in the substance supply and dealers’ adaptative behaviors, mimicking efficient prior strategies to expand toward new markets, such as micro-networks and home delivery as observed in heroin retail sales (Lahaie, Janssen, and Cadet-Taïrou Citation2015).

The odds of using the less stigmatizing “smoked cocaine” were higher among those of higher SES. On its own, this result demonstrates how those with higher status are less willing to apply the stigmatized crack label to themselves. Such distinctions act to perpetuate the association of “crack” with those who are underprivileged even when committing the exact same act. The effect of SES becomes more apparent through the inclusion of an interaction with region. Outside the Paris region, SES is of less consequence because the odds of using the “smoked cocaine” label are consistently high regardless of SES. However, the gap between self-application of “crack user” versus “smoked cocaine” narrows across SES within the Paris region. This result suggests that the most advantaged people who use crack cocaine located in the Paris region refer to “smoking cocaine” as a way to differentiate themselves from the ill-perceived “crack users.” The inclusion of an interaction term enlightens a polarized perception of crack in the Paris metropolitan region, which has been placed under intense and potentially biased media scrutiny (Pialoux Citation2021).

While reasonable to attribute the use of “smoking cocaine” by those of high SES and outside Paris to the desire to differentiate themselves, an accompanying corollary question is why those of low SES and in the Paris region continue to self-apply the more stigmatizing label of using crack. While we cannot adjudicate between them based on our analysis, we offer two possible explanations. The first possibility is that the term “crack user” is not as stigmatizing among low-SES Parisians who use crack cocaine. As noted above, Furst et al. (Citation1999) demonstrated that the “crackhead” label became highly stigmatized in U.S. urban areas in the 1980s and 1990s, resulting in young people avoiding crack cocaine and contributing to decreases in its use. However, they end their article by cautioning that as crack cocaine use decreases, the label could lose some of its stigmatizing qualities. In our results then, the fact that this label is more common among those of low SES and in the Paris region could be construed as evidence that some of the stigma of “crack user” has been lost among such individuals. However, given that crack cocaine use is very rare in the general population in France (for example, last year use was 0.2% in 2017 and 0.1% in 2014; Spilka et al. Citation2018), there is no particular reason that the loss of stigma of “crack user” would be confined to such individuals.

Another explanation is that low-SES Parisians who use crack cocaine have reduced access to the “smoking cocaine” label. Within medical sociology, the Theory of Fundamental Causes posits that as medical practices change, those of the highest SES will benefit most from it, as they have the knowledge, power, and financial resources to take advantage of such changes and avoid certain health risks (Link and Phelan Citation1995, Citation1996; Phelan, Link, and Tehranifar Citation2010). As such individuals seek treatment or other services, they are likely to frequent medical settings where “smoking cocaine” is more common than “using crack” and to interact with health professionals who use the former more often in their daily work. Health professionals may inadvertently provide high SES individuals with the benefit of the doubt concerning their behavior and apply the less stigmatizing label, while spreading knowledge of the less stigmatizing labels disproportionately to such patients who then go on to diffuse this knowledge within their similarly positioned social networks. For those of low SES and in the Paris region, the use of the more stigmatizing “crack user” label may result from reduced access to spaces in which the “smoking cocaine” label is used, and resultant social networks that then do not use this label.

Thus, labeling and self-defining are no trivial issues in our particular case. According to recent health professionals’ feedback, some people deny using “crack” but agree to “smoking cocaine,” creating a notable confusion amid this clientele. For instance, economically advantaged people who use cocaine hydrochloride may frequent private treatment where they are exposed to less stigmatizing labels or may not label their use as problematic. Further, individuals who use highly stigmatized drugs may avoid treatment altogether or disengage with it under the assumption that treatment will be the cause of attachment of the label to them (Paquette, Syvertsen, and Pollini Citation2018; Radcliffe and Stevens Citation2008). Thus, the confusion is somewhat noteworthy as it is likely to interfere with clinical treatment procedures and, from an epidemiological perspective, produce downward biased results in estimating prevalence (Janssen et al. Citation2021). In an effort to address this emerging labeling distinction, treatment centers have begun to use the differing labels in the treatment process, which is important in order to accurately recognize and treat substance use issues, as well as to allow people who use drugs agency in how they view themselves.

But if this self-identification is unequal by important clientele characteristics, then embedding the labeling distinction within health settings can serve to indirectly perpetuate inequalities. Further, the random effect in our models unveiled heterogeneity in treatment center labeling, which could reflect how the substance has been queried in recent years across treatment centers, alongside in-depth changes in a more heterogenous population of people who use crack cocaine. Thus, we need to remain cognizant of how labels become embedded at the local level. However, treatment centers can also be used as a site to lessen the stigma associated with certain labels if all individuals have equal access and treatment who present with the same substance even if labeled differently. Additionally, the move toward person-first language in addiction settings and research is another avenue for reducing stigmatizing labels (Kelly and Westerhoff Citation2010; McGinty and Barry Citation2020).

Our study also highlights how labeling practices may be related to resurgences in substances. In order to overcome the barrier of the stigmatized label “crack,” crack cocaine may gain new adherents through renaming, propagating the idea that these are different substances. This reconception is similar to another current trend in substance use: a notable proportion of people who use the substance tend to differentiate MDMA from ecstasy, regarded as separate substances with specific psychoactive (side) effects. Some people who use this substance genuinely believe that both labels refer to separate substances, despite sharing the same active component. In both France and Norway, research shows that so-labeled “MDMA” is more in fashion and with better effects, with older people who use the substance less capable of handling the intensity of the effects associated with MDMA (Edland-Gryt et al. Citation2017; Girard and Bosher Citation2010) in a context of increasing availability of high purity products (EMCDDA Citation2016). For MDMA versus ecstasy, the labeling distinction appears to be largely generational, a way of drawing boundaries between young and old social circles. By contrast, our results suggest that the distinction of crack use versus smoking cocaine was influenced jointly by geographic location and socioeconomic status. While age distinctions in the MDMA research are an important finding, the crack labeling distinctions have implications for inequality and potentially treatment.

We note some limitations of our study. First, the study used treatment center data, an advantageous approach for accessing this particularly hard-to-reach population. However, this data source is not representative of the entire population people who use crack cocaine in France. Treatment centers are likely to underrepresent people whose use is casual recreational or heavy who have not sought treatment or are in harm reduction facilities. Second, the study considered two labels, discarding the more recent term of “based cocaine” of increasing use among those who use recreationally or on the streets. Much less is known about this term as a self-label, such that future research is necessary. Relatedly, the practice of injecting crack cocaine has been noted in the literature (Cadet-Taïrou et al. Citation2021; Harris et al. Citation2019). As injection generally is highly stigmatized among routes of administration (Rivera et al. Citation2014), individuals may have used the label “smoked cocaine” to make this distinction. As injection of crack cocaine even among those using the “used crack” label in this treatment-center-based sample is rare (1.1%), this association may only be perceptual, but nonetheless could be a consideration in self-labeling. Third, while this quantitative study is able to examine associations between certain factors and self-labeling, it cannot uncover what these labels mean for identity and why people use them. For example, are these processes subconscious distinctions or explicit identity boundary work conducted for the purpose of making such distinctions? Qualitative studies, however, have noted the importance of labeling distinctions among people who use drugs (Boeri Citation2004; Copes Citation2016; Copes et al. Citation2008; Draus et al. Citation2010; Rødner Citation2005; Sandberg Citation2012). We view our study as a quantitative companion to this research, but nonetheless encourage qualitative studies on the specific distinction of the label of crack use versus smoking cocaine.

Finally, by law the data make no reference whatsoever to ethnicity. We recognize the importance of race and ethnicity, especially given the historical and lasting association of crack cocaine use with Black people in the U.S. (Alexander Citation2012; Lindsay and Vuolo Citation2021; Reinarman and Levine Citation2004). In the French context, there is likely a similar association given that crack cocaine was introduced in mainland France by migrants from outer sea territories (Caribbean), with supply first taken over by communities from Western Africa. Indeed, the identification of such migrants could be considered a proxy for discussions of race and crack cocaine (Goulian et al. Citation2022). Without information on race in France, crack cocaine has been historically viewed through a social class lens as a result (Goulian et al. Citation2022), and minorities are known to be overrepresented among low SES individuals. Thus, we would venture that ethnicity is likely a salient distinguishing factor in self-application of labels in France, in which non-minority individuals might use “smoked cocaine” as a way to distance themselves from a behavior disproportionately associated with minorities. We note that we are using terms such as “minority” and “non-minority” because identification for race/ethnicity used in other national contexts (e.g., White, Black) do not formally exist in France by both law and cultural tradition for the expressed purpose of preventing discrimination through categorization.

Conclusions

Labels do matter for personal self-appraisals, which is key to individual identity. However, some labels, such as that of a “crack user,” are highly stigmatizing. As we show, roughly half of treatment center patients in France elect to use the alternative “smoked cocaine” label, which can be viewed as a potentially less stigmatizing label for the exact same activity. The findings of the study have implications for the formulation of efficient interventions and guidance of health professionals. Keeping up with drug names and practices is a challenge worthy of being taken on, as it facilitates identification of those who use particular substances and associated practices. In France, tighter cooperation with harm-reduction facilities’ professionals (a separate entity to treatment centers) could further help to understand street-level labeling trends. However, we also show the potential danger of taking the labels at face value without considering the background profiles of individuals who use a substance with multiple labels. When less stigmatized labels are also used by those of relatively higher status, labeling can create boundaries that allow the less privileged to remain stigmatized. However, through awareness of this labeling, health professionals can aim to lessen such stigmatization through treating the labels equally, which could have indirect effects on how the labels are viewed at large.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Disclosure statement

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mike Vuolo

Mike Vuolo is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at The Ohio State University and current editor of Sociological Methodology. His research interests include crime, law, and deviance; health; employment; substance use; the life course; and statistics and methodology.

Eric Janssen

Eric Janssen has been working for the past 15 years at the French Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction. His research interests include substance use among youth, social and economic inequalities in substance use, hard-to-reach populations, and statistical methods.

Ivette Flores Laffont

Ivette Flores Laffont is Professor-Researcher in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophical, Methodological and Instrumental Disciplines at Centro Universitario de Tonalá of the University of Guadalajara. Her main research interests are migration and ethnicity, indigenous education in urban contexts, and urban socio-cultural processes.

References

- Alexander, Michelle. 2012. New Jim Crow - Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

- Bayer, R. and J. Stuber. 2006. ”Tobacco Control, Stigma, and Public Health: Rethinking the Relations.” American Journal of Public Health 96(1):47–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2005.071886.

- Becker, Howard. 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

- Beckett, Katherine. 1997. Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, K., A. Salmon, M. Bowers, J. Bell, and L. McCullough. 2010. ”Smoking, Stigma and Tobacco ‘Denormalization’: Further Reflections on the Use of Stigma as a Public Health Tool. A Commentary on Social Science & Medicine’s Stigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and Health Special Issue (67: 3).” Social Science & Medicine 70(6):795–99. ( discussion 800-1). doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.060.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism; Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

- Boeri, Miriam Williams. 2004. ”’Hell, I’m an Addict, but I Ain’t No Junkie’: An Ethnographic Analysis of Aging Heroin Users.” Human Organization 63:236–45. doi:10.17730/humo.63.2.p36eqah3w46pn8t2.

- Cadet-Taïrou, Agnès, Marie Jauffret-Roustide, Michel Gandhilon, Sayon Dembelé, and Candy Jangal. 2021. “Main Results of the Crack Study in the Ile-de-France Region - Overview.” OFDT, INSERM, Survey Results Note 2021-03, Paris. (http://en.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/eisaac2b1.pdf).

- Ciccarone, D. 2021. ”The Rise of Illicit Fentanyls, Stimulants and the Fourth Wave of the Opioid Overdose Crisis.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 34(4):344–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000717.

- Copes, Heith. 2016. ”A Narrative Approach to Studying Symbolic Boundaries Among Drug Users: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis.” Crime, Media, Culture 12(2):193–213. doi:10.1177/1741659016641720.

- Copes, Heith, Andy Hochstetler, and J Patrick Williams. 2008. ”’We Weren’t Like No Regular Dope Fiends’: Negotiating Hustler and Crackhead Identities.” Social Problems 55:254–70. doi:10.1525/sp.2008.55.2.254.

- Daniulaityte, R., R. Falck, and R. G. Carlson. 2012. ”’I’m Not Afraid of Those Ones Just ‘Cause They’Ve Been Prescribed’: Perceptions of Risk Among Illicit Users of Pharmaceutical Opioids.” International Journal of Drug Policy 23:374–84. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.01.012.

- De Oliveira, Lúcio Garcia, Lúcia Pereira Barroso, Camila Magalhães Silveira, Zila Van Der Meer Sanchez, Julio De Carvalho Ponce, Leonardo José Vaz, and Solange Aparecida Nappo. 2009. ”Neuropsychological Assessment of Current and Past Crack Cocaine Users.” Substance Use & Misuse 44(13):1941–57. doi:10.3109/10826080902848897.

- Draus, Paul J., Juliette Roddy, and Mark Greenwald. 2010. ”’I Always Kept a Job’: Income Generation, Heroin Use and Economic Uncertainty in 21st Century Detroit.” Journal of Drug Issues 40:841–69. doi:10.1177/002204261004000405.

- Edland-Gryt, M., S. Sandberg, and W. Pedersen. 2017. ”From Ecstasy to MDMA: Recreational Drug Use, Symbolic Boundaries, and Drug Trends.” International Journal of Drug Policy 50:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.030.

- EMCDDA. 2016. “Recent changes in Europe’s MDMA/ecstasy market. Results from an EMCDDA trendspotter study.” Lisbon: EMCDDA . https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/2473/TD0116348ENN.pdf

- EMCDDA. 2019. “European Drug Report 2018: Trends and Developments.” Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11364/20191724_TDAT19001ENN_PDF.pdf

- Escobar, M., J. N. Scherer, C. M. Soares, L. S. P. Guimarães, M. E. Hagen, L. von Diemen, and F. Pechansky. 2018. ”Active Brazilian Crack Cocaine Users: Nutritional, Anthropometric, and Drug Use Profiles.” Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 40(4):354–60. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2409.

- Falck, Russel S., Jichuan Wang, Robert G. Carlson, and Harvey A. Siegal. 2000. ”Crack-Cocaine Use and Health Status as Defined by the SF-36.” Addictive Behaviors 25(4):579–84. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(99)00040-4.

- Falck, Russel S., Jichuan Wang, Harvey A. Siegal, and Robert G. Carlson. 2004. ”The Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder Among a Community Sample of Crack Cocaine Users: An Exploratory Study with Practical Implications.” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192(7):503–07. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000131913.94916.d5.

- Furst, R. Terry, D. Johnson Bruce, Eloise Dunlap, and Richard Curtis. 1999. ”The Stigmatized Image of the ’‘Crack Head’’: A Sociocultural Exploration of a Barrier to Cocaine Smoking Among a Cohort of Youth in New York City.” Deviant Behavior 20(2):153–81. doi:10.1080/016396299266542.

- Gérome, C., A. Cadet-Taïrou, M. Gandilhon, M. Milhet, M. Martinez, and T. Néfau. 2018. ”Psychoactive Substances, Users and Markets: Recent Trends (2017-2018) [Substances Psychoactives, Usagers Et Marchés: Les Tendances Récentes (2017-2018)].”Tendances 129:1–8. https://en.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/eftacgyc.pdf.

- Girard, Guillaume and Gwenäelle Bosher. 2010. ”Ecstasy, from Infatuation to Has-Been [L’Ecstasy, de L’Engouement À la « Ringardisation ».” in Pp. 96–105 in Les Usages de Drogues Illicites En France Depuis 1999 Vus Au Travers du Dispositif TREND, edited by J. M. Costes. Paris: OFDT,

- Glantz, S. A. and D. W. Bareham. 2018. ”E-Cigarettes: Use, Effects on Smoking, Risks, and Policy Implications.” Annual Review of Public Health 39(1):215–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013757.

- Goulian, A., M. Jauffret-Roustide, S. Dambélé, R. Singh, and R. E. Fullilove 3rd. 2022. ”A Cultural and Political Difference: Comparing the Racial and Social Framing of Population Crack Cocaine Use Between the United States and France.” Harm Reduction Journal 19(1):44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00625-5.

- Harris, Magdalena, Jenny Scott, Talen Wright, Rachel Brathwaite, Daniel Ciccarone, and Vivian Hope. 2019. ”Injecting-Related Health Harms and Overuse of Acidifiers Among People Who Inject Heroin and Crack Cocaine in London: A Mixed-Methods Study.” Harm Reduction Journal 16(1):60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0330-6.

- Hatsukami, D. K. and M. W. Fischman. 1996. ”Crack Cocaine and Cocaine Hydrochloride. Are the Differences Myth or Reality?” Jama 276:1580–88. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540190052029.

- Hay, G., A. Rael dos Santos, H. Reed, and V. Hope. 2019. “Estimates of the Prevalence of Opiate Use And/or Crack Cocaine Use, 2016/17: Sweep 13 Report.” Liverpool: Public Health England, John Moores University. https://phi.ljmu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Estimates-of-the-Prevalence-of-Opiate-Use-and-or-Crack-Cocaine-Use-2016-17-Sweep-13-report.pdf

- Hedeker, D. 2003. ”A Mixed-Effects Multinomial Logistic Regression Model.” Statistics in Medicine 22(9):1433–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1522.

- Heimer, Karen and Ross L. Matsueda. 1994. ”Role-Taking, Role Commitment, and Delinquency: A Theory of Differential Social Control.” American Sociological Review 59(3):365–90. doi:10.2307/2095939.

- Janssen, Eric, Agnès Cadet-Taïrou, Clément Gérome, and Michael Vuolo. 2020. ”Estimating the Size of Crack Cocaine Users in France: Methods for an Elusive Population with High Heterogeneity.” International Journal of Drug Policy 76:e102637. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102637.

- Janssen, Eric, Mike Vuolo, Clément Gérome, and Agnès Cadet-Taïrou. 2021. ”Mixed Methods to Assess the Use of Rare Illicit Psychoactive Substances: A Case Study.” Epidemiologic Methods 10. doi: 10.1515/em-2020-0031.

- Kelly, J. F. and C. M. Westerhoff. 2010. ”Does It Matter How We Refer to Individuals with Substance-Related Conditions? a Randomized Study of Two Commonly Used Terms.” International Journal of Drug Policy 21:202–07. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.010.

- Kitsuse, John I. 1980. ”Coming Out All Over: Deviants and the Politics of Social Problems.” Social Problems 28(1):1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/800377.

- Lahaie, E., E. Janssen, and A. Cadet-Taïrou. 2015. ”Determinants of Heroin Retail Prices in Metropolitan France: Discounts, Purity and Local Markets.” Drug and Alcohol Review 35(5):597–604. doi:10.1111/dar.12355.

- Lemert, Edwin M. 1951. Social Pathology: A Systematic Approach to the Theory of Sociopathic Behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lindsay, Sadé L., and Mike Vuolo. 2021. ”Criminalized or Medicalized? Examining the Role of Race in Responses to Drug Use.” Social Problems 68:942–63. doi:10.1093/socpro/spab027.

- Link, B. G. and J. Phelan. 1995. ”Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35:80–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2626958.

- Link, B. G. and J. C. Phelan. 1996. ”Understanding Sociodemographic Differences in Health--The Role of Fundamental Social Causes.” American Journal of Public Health 86(4):471–73. doi:10.2105/ajph.86.4.471.

- Matsueda, Ross L. 1992. ”Reflected Appraisals, Parental Labeling, and Delinquency: Specifying a Symbolic Interactionist Theory.” The American Journal of Sociology 97(6):1577–611. doi:10.1086/229940.

- McGinty, E. E. and C. L. Barry. 2020. ”Stigma Reduction to Combat the Addiction Crisis — Developing an Evidence Base.” The New England Journal of Medicine 382(14):1291–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2000227.

- Mead, George Herbert. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society from the Standpoint of a Social Behavorist edited by C. W. Morris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Merlo, J., B. Chaix, H. Ohlsson, A. Beckman, K. Johnell, P. Hjerpe, L. Råstam, and K. Larsen. 2006. ”A Brief Conceptual Tutorial of Multilevel Analysis in Social Epidemiology: Using Measures of Clustering in Multilevel Logistic Regression to Investigate Contextual Phenomena.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60(4):290–97. doi:10.1136/jech.2004.029454.

- Palle, C. 2021. ”Clients Serviced in Treatment Centres - Situation in 2019 and Changes Since 2015 [Les Personnes Accueillies Dans Les CSAPA - Situation En 2019 Et Évolution 2015-2019.” Tendances 146. (https://www.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/eftxcp2b8.pdf).

- Paquette, C. E., J. L. Syvertsen, and R. A. Pollini. 2018. ”Stigma at Every Turn: Health Services Experiences Among People Who Inject Drugs.” International Journal of Drug Policy 57:104–10. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.004.

- Pérez, Alberto Oteo, Maarten J. L. F. Cruyff, Annemieke Benschop, and Dirk J. Korf. 2013. ”Estimating the Prevalence of Crack Dependence Using Capture-Recapture with Institutional and Field Data: A Three-City Study in the Netherlands.” Substance Use & Misuse 48(1–2):173–80. doi:10.3109/10826084.2012.748073.

- Phelan, J. C., B. G. Link, and P. Tehranifar. 2010. “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health Inequalities: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51:S28–40. 10.1177/0022146510383498.

- Pialoux, Gilles. 2021. ”Le Drame du Crack Au Risque des Médias.”Swaps 100:6–8. https://vih.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/SWAPS100.pdf.

- Prangnell, Amy, Huiru Dong, Patricia Daly, M. J. Milloy, Thomas Kerr, and Kanna Hayashi. 2017. ”Declining Rates of Health Problems Associated with Crack Smoking During the Expansion of Crack Pipe Distribution in Vancouver, Canada.” BMC Public Health 17(1):163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4099-9.

- Radcliffe, P. and A. Stevens. 2008. ”Are Drug Treatment Services Only for ‘Thieving Junkie Scumbags’? Drug Users and the Management of Stigmatised Identities.” Social Science & Medicine 67:1065–73. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.004.

- Reinarman, Craig and Harry G. Levine. 2004. ”Crack in the Rearview Mirror: Deconstructing Drug War Mythology.” Social Justice 31:182–99. doi:10.2307/29768248.

- Restrepo, Carlos S., Jorge A. Carrillo, Santiago Martínez, Paulina Ojeda, Aura L. Rivera, and Ami Hatta. 2007. ”Pulmonary Complications from Cocaine and Cocaine-Based Substances: Imaging Manifestations.” RadioGraphics 27(4):941–56. doi:10.1148/rg.274065144.

- Rivera, A. V., J. DeCuir, N. D. Crawford, S. Amesty, and C. F. Lewis. 2014. ”Internalized Stigma and Sterile Syringe Use Among People Who Inject Drugs in New York City, 2010-2012.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 144:259–64. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.778.

- Rødner, Sharon. 2005. ”“I Am Not a Drug Abuser, I Am a Drug User”: A Discourse Analysis of 44 Drug Users’ Construction of Identity.” Addiction Research & Theory 13:333–46. doi:10.1080/16066350500136276.

- Sandberg, Sveinung. 2012. ”Is Cannabis Use Normalized, Celebrated or Neutralized? Analysing Talk as Action.” Addiction Research & Theory 20:372–81. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.638147.

- Schwalbe, Michael, Sandra Godwin, Daphne Holden, Douglas Schrock, Shealy Thompson, and Michele Wolkomir. 2000. ”Generic Processes in the Reproduction of Inequality: An Interactionist Analysis.” Social Forces 79(2):419–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2675505.

- Snow, David A. and Leon Anderson. 1987. ”Identity Work Among the Homeless: The Verbal Construction and Avowal of Personal Identities.” The American Journal of Sociology 92(6):1336–71. doi:10.1086/228668.

- Spilka, S., J. B. Richard, O. Le Nézet, E. Janssen, A. Brissot, A. Philippon, Jalpa Shah, S. Chyderiotis, R. Andler, and C. Cogordan. 2018. ”Levels of Illicit Drug Use in France in 2017.”Tendances 128:1–6. https://en.ofdt.fr/BDD/publications/docs/eftassyb.pdf.

- Story, A., G. Bothamley, and A. Hayward. 2008. ”Crack Cocaine and Infectious Tuberculosis.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 14(9):1466–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1409.070654.

- Stuber, J., S. Galea, and B. G. Link. 2008. ”Smoking and the Emergence of a Stigmatized Social Status.” Social Science & Medicine 67(3):420–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.010.

- Thoits, Peggy A. 2011. ”Resisting the Stigma of Mental Illness.” Social Psychology Quarterly 74(1):6–28. doi:10.1177/0190272511398019.