Abstract

Objectives

Determine whether the Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) is a useful screening instrument for Fear of Childbirth (FoC) and examine the potential added value of screening by analyzing how often pregnant women discuss their FoC during consultation.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey study included nulliparous pregnant women of all gestational ages, recruited via the internet, hospital and midwifery practices. The online questionnaires included the FOBS and Wijma Delivery Expectations Questionnaire version A (W-DEQ A). The latter was used as golden standard for assessing FoC (cutoff: ≥85).

Results

Of the 364 included women, 67 (18.4%) had FoC according to the W-DEQ A. Using the FOBS with a cutoff score of ≥49, the sensitivity was 82.1% and the specificity 81.1%, with 111 (30.5%) women identified as having FoC. Positive predictive value was 49.5% and negative predictive value 95.3%. Of the women with FoC (FOBS ≥49), 68 (61.3%) did not discuss FoC with their caregiver.

Conclusion

The FOBS is a useful screening instrument for FoC. A positive score must be followed by further assessment, either by discussing it during consultation or additional evaluation with the W-DEQ A. The majority of pregnant women with FoC do not discuss their fears, underscoring the need for screening.

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are major events. The level of apprehension pregnant women experience about giving birth varies on a continuum, from nonexistent through severe [Citation1]. Low levels of apprehension are reported by almost half of pregnant women and are considered normal [Citation2], but fear of childbirth (FoC), defined as fear and anxiety when facing birth [Citation3], can be severe and interfere with functioning.

Different prevalence rates for FoC are found in different countries, ranging from 8% to 23%, and have increased in recent years [Citation4]. A recent systematic review on FoC found an average prevalence rate of 11% for FoC as measured by the Wijma Delivery Expectations Questionnaire version A (W-DEQ A) using a cutoff of ≥85 [Citation5]. Higher levels of fear are seen more often in women who are nulliparous [Citation6], younger [Citation7] and those who have poor psychological health and little social support [Citation8].

FoC may lead to negative psychological and physical consequences and outcomes [Citation6,Citation9–12]. Women with FoC, report more physical symptoms, visit their obstetric caregiver more often and have more sick-days during their pregnancy than women without FOC [Citation9]. Duration of labor is significantly longer in women with FoC [Citation10] and severe FoC is found to be an important risk factors for postpartum PTSD [Citation11,Citation12]. The preferred mode of delivery is significantly associated with FoC, with women who preferred a cesarean section reporting stronger fear [Citation6]. In this way, FoC can lead to unnecessary medical interventions.

Since FoC is common and has negative consequences, it is important to identify FoC in pregnancy. The W-DEQ A is the most widely used questionnaire for measuring FoC in research [Citation13] and is well validated [Citation14,Citation15]. However screening for FoC in clinical practice is not common. The W-DEQ A is often too long to use as a standard screening instrument in clinical practice [Citation16], can be difficult to understand for women who have to fill it out [Citation17] and needs considerable time to score before it can be discussed during consultation, which makes it impractical. A short and easy to score screening instrument would be more useful and could increase the likelihood to integrate screening for FoC in the clinical routine of gynecologists and midwifes.

The Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) is a two-item visual analogue scale which is quick and easy to use and could be an alternative to assess FoC. The FOBS has already been validated for use in Swedish and Australian populations [Citation16,Citation18], but it has not been validated in a Dutch sample yet.

Moreover, little research has been conducted on how often pregnant women discuss FoC with their midwife or gynecologist during their checkups. In one study [Citation19], 32% of gynecologists reported to always ask about FoC and 55% only asked about it in specific situations, e.g. when there were signs of FoC which could be observed during interactions with the patient at checkups. In cases of obvious signs of FoC, 82% of the gynecologists would make a referral to a mental health worker. These findings suggest that pregnant women without obvious signs of FoC may go unidentified as fearful by their obstetric caregiver. The importance of timely screening for FoC lies in being able to reduce the anxiety as early as possible, potentially avoiding unnecessary medical interventions and help with preparation for childbirth [Citation6].

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to determine whether the Dutch version of the two-item FOBS is a suitable screening instrument for FoC, using the W-DEQ A as golden standard. The second aim was to determine how many pregnant women, discussed FoC with their midwife or gynecologist during consultation. In this way, we wanted to examine whether screening would have added value in the identification of pregnant women with FoC in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Participants and research design

The data for this cross-sectional survey study were originally collected for the HEAR-study (Prevalence and course of fear of childbirth during pregnancy and need for help in nulliparous women: A cohort study). The main objective of the HEAR- study was to obtain insight in the course of FoC according to gestational age in nulliparous women and to assess the need for help for FoC.

Nulliparous pregnant women of all gestational ages were eligible for participation in the current study. Inclusion criteria were being pregnant, aged ≥18 years, never having given birth before (no pregnancy ≥16 weeks) and being able to read Dutch.

Procedure

Via Internet (social media, website Capture group and general hospital OLVG), flyers at an urban hospital (OLVG) and several community midwifery practices in Amsterdam and east of the Netherlands (Ede), women were informed about the study. Through a link on internet, potential participants could get further information about the study. When they agreed to participate and filled out an informed consent, they provided their e-mail address. After their e-mail address was checked to be unique, they received an e-mail with a personalized link to the online survey. In case a participant did not fill out both the W-DEQ A and the FOBS, they were excluded from the analyses in the current study. Data were collected between February 2019 and January 2020. Ethical approval was granted by the Medical Research Ethic Committees united (MEC-U) In Nieuwegein, the Netherlands on the 13 November 2018 (reference number: W 18-188).

Measures

The online survey, using CASTOR EDC software [Citation20], included questions regarding demographic, psycho-social, obstetrical, and pregnancy-related information.

The Wijma Delivery Expectations Questionnaire version A (W-DEQ A) was used as a golden standard for assessing FoC. The W-DEQ-A is a 33-item self-report rating scale. Items are scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from ‘not at all’ (=0) to ‘extremely’ (=5). Total scores vary from 0 to 165, with higher scores indicating a higher level of FoC. The W-DEQ A has good psychometric properties with a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha= 0.87) [Citation14]. The W-DEQ A has a validated cutoff score of ≥85 for clinically relevant FoC [Citation14]. In a recent study [Citation15], a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 93.8% was found with this cutoff score using the SCID-5 as golden standard for assessing FoC.

The Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) is a two-item self-report Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [Citation16]. The FOBS consists of one question: ‘How do you feel right now about the approaching birth?’ Respondents answer by placing a mark on each of two 100-mm lines with anchors defined as (a) ‘calm’ and ‘worried’ and (b) ‘no fear’ and ‘strong fear’. The scores on the two lines are measured and averaged to get a total score ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicating higher levels of FoC. For this study, the FOBS was translated into Dutch. Its back translation was approved by the authors of the FOBS (Dr Haines and Dr Hildingsson). Previous research has shown a high internal consistency with a Cronbach Alpha of 0.91 [Citation16] and 0.92 [Citation21] and inter-item consistency of 0.85 [Citation21].

Furthermore, women were asked whether they had discussed FoC with their gynecologist or midwife (yes or no), how satisfied they were about this conversation measured (five-point Likert scale, ranging from very dissatisfied to very satisfied), and if they felt free to discuss concerns about the approaching delivery (totally disagree to totally agree).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline characteristics, W-DEQ A and FOBS scores in absolute numbers and percentages. To investigate the strength of the association between scores on the W-DEQ A and FOBS, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated. Internal consistency of the FOBS was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha.

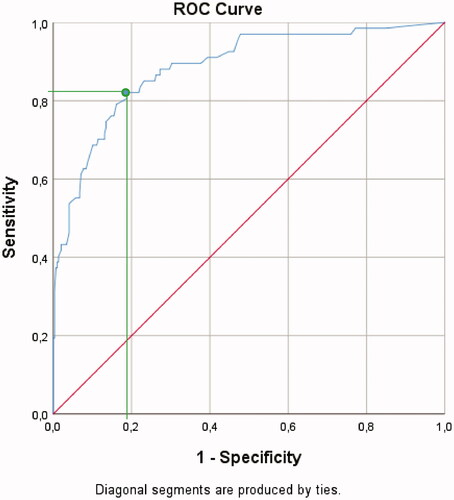

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was computed to investigate the optimal cutoff point for the FOBS. In defining the cutoff point, our aim was to both maximize the classification rate of women with FOC and minimize the misclassification rate. Therefore, the cutoff was determined by the value for which both the sensitivity and 1-specificity are at the maximal point. The area under the curve (AUC) was used to investigate the overall test accuracy of the FOBS in correctly detecting pregnant women with FoC.

Based on the W-DEQ A as golden standard measure, FOBS scores were defined as true positive (TP; correctly identified as case of FoC), true negative (TN; correctly identified as non-case of FoC), false positive (FP; incorrectly identified as case of FoC), and false negative (FN; incorrectly identified as non-case of FoC). The true positive rate/sensitivity is the probability that the FOBS was positive when FoC was present according to the W-DEQ A (TP/[TP + FN]). The probability that the FOBS was negative when clinically relevant FoC was absent according to the W-DEQ A is the true negative rate/specificity (TN/[TN + FP]). The positive predictive value is the probability that a pregnant woman had a positive score on the W-DEQ A when the FOBS was positive (TP/[TP + FP]) and the probability that a pregnant woman had a negative score on the W-DEQ A when the FOBS was negative is known as the negative predictive value (TN/[TN + FN]). For the group of pregnant women with and without FoC according to the FOBS, we calculated the proportion of women who discussed FoC, the portion that was satisfied about discussing FoC and the proportion of women who felt they could discuss their concerns with their caregiver.

Bivariate logistic regression analyses were used to investigate which demographic, obstetric and psychosocial variables assessed at baseline were associated with FoC (FOBS score 0 if below and 1 if above the cutoff). Variables associated with FoC with p-values <0.2 were subsequently entered in a multivariate logistic regression model to assess their independent association with FoC using the score on the FOBS (above or under the cutoff score) as dependent measure. Results of regression analyses are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Means and standard deviations are given as M (SD). Median and inter-quartile range were presented if data were skewed. All statistical analyses were preformed using SPSS for Windows version 24.0 [Citation22].

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 566 women agreed to participate of whom 378 (66.8%) completed the questionnaire. Fourteen women were excluded because they did not report gestational age (n = 12) or were multiparous (n = 2). These participants were excluded from all analyses. shows characteristics of the study population (N = 364). The mean age was 30.7 years (SD= 4.3), which is comparable with the mean age of Dutch nulliparous women having their first child (mean age 2019 = 30.0) [Citation23]. The average number of weeks pregnancy was 25.6 (SD= 9.9). In our study population of nulliparous pregnant women of all gestational ages, 72.5% was in primary care. These rates are comparable to the Dutch population in which 86.9% of nulliparous women are in primary care at the start of their pregnancy and 50.6% remain so until their delivery [Citation24]. Compared to Dutch women in the age of 25–35 years, of whom 51.8% is highly educated [Citation25], highly educated women were overrepresented (71.7%) in our sample. In the study sample with young women 47.8% reported a history of psychological treatment, somewhat higher than the lifetime prevalence of psychological problems in the Dutch population 42.7% [Citation26].

Table 1. participant characteristics.

Screening for fear of childbirth with the FOBS

The scores on the W-DEQ A were normally distributed and the mean score was 65.8 (SD = 23.0), with scores ranging from 1 to 146. In our sample, 67 women (18.4%) had clinically relevant FoC according to the W-DEQ A (score ≥85). The internal consistency of the W-DEQ A was .94 (Cronbach’s alfa).

The scores on the FOBS were positively skewed with a median of 26.5 (IQR 11–52.5) and scores ranging from 0 to 100. The Spearman’s Rho correlation between the W-DEQ A and FOBS was .72 (p < 0.001).

The internal consistency of the FOBS was .91 (Cronbach’s alfa). The overall accuracy (AUC) of the FOBS to detect FoC was 88.5% (p < 0.001), with a confidence interval (95%) of 83.9–93.2%.

The optimal cutoff score on the FOBS was selected using the ROC-curve by determining the value for which both the sensitivity and specificity were at the maximal point (nearest to 1 in the upper left corner). In this way, the cutoff had the best tradeoff between a high proportion of true positives and a small portion of false positives (1-specificity) ().

At the optimal cutoff score of FOBS ≥49, 111/364 women (30.5%) were identified as a case. Fifty-five women (15.1%) were fearful according to both the W-DEQ A and FOBS. The results of the sensitivity analysis and the positive and negative predictability are shown in . The probability that the FOBS is positive when FoC is present according to the W-DEQ A (sensitivity) was 82.1% (55 of the 67 women who scored ≥85 on the W-DEQ A). The probability that the FOBS was <49 when there is no FoC according to the W-DEQ A (specificity) was 81.1% (241 of the 297 women who scored <85 on the W-DEQ A). The probability that a woman was selected as a case according to the W-DEQ A when the FOBS was positive (positive predictive value) was 49.5% (55/111 women). The probability that a woman had no FoC according to the W-DEQ A when the FOBS was negative (negative predictive value) was 95.3% (241/253 women).

Table 2. Detecting FoC with the FOBS at a cutoff score ≥49.

A multiple logistic regression analysis (method backward) showed that, compared to women without FoC, women with FoC according to the FOBS significantly more often had a previous history of psychological treatment (65/111, 58.6% versus 109/253, 43.1%) with an OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.19–2.98, p = 0.006 and more often had an unplanned pregnancy (21/111, 18.9% versus 28/253, 11.1%) with an OR ratio 1.92; 95% CI 1.03–3.58, p = 0.041.

Incidence and satisfaction of discussing FoC during consultation

Of all women, 307/364 (84.3%) had the feeling they could talk about concerns about the approaching delivery. Women with FoC significantly less often reported having the feeling they could discuss their concerns about the approaching delivery compared to women without FoC. Of the women with FoC, 43/111 (38.7%) discussed FoC with their caregiver which is significantly more than women without FoC, of which 47/253 (18.6%) discussed FOC. Regarding satisfaction with these conversations, women with FoC were significantly more often dissatisfied or very dissatisfied as compared to women without FoC (see ).

Table 3. Incidence and satisfaction of discussing FoC.

Discussion

The first objective of this study was to determine whether the Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) can be used as screening instrument for FoC. It can be concluded that the Dutch version of the FOBS can help identify pregnant women with clinically relevant FoC. It is easy to fill out, has a high internal consistency, good overall accuracy and a high negative predictive value. The high negative predictive value is an advantage for clinical practice because it can give a high certainty-rate for filtering out women who are not fearful for delivery. The tendency of the FOBS to over-identify women as fearful for delivery, which leads to a relative low positive predictive value, was not only found in our study but also in previous studies [Citation4]. Therefore, a score above the cutoff on the FOBS must be followed by further assessment, either by discussing FoC during consultation or by additional evaluation with the W-DEQ A. This way, women with clinically relevant FoC can be differentiated from women without clinically relevant FoC, who still score above the cutoff score on the FOBS.

In a previous study [Citation16], a cutoff score of ≥54 on the FOBS was advised, with a sensitivity of 89%, a specificity of 79%, a positive predictive value of 85%, and a negative predictive value of 79%. This study was conducted among Australian nulliparous and multiparous women in their second trimester of pregnancy. In our study, with a Dutch sample of nulliparous women of all gestational ages, a cutoff score of ≥49 was found with a sensitivity of 82.7% and a specificity of 79.4%. The lower cutoff score, as used in the present study, leads to a lower positive predictive value, but a higher negative predictive value. In combination with additional assessment, using a lower cutoff score will lead to the identification of more women with clinical relevant FoC according to the golden standard. As found in our study, four out of five women without FOC rated discussing concerns about the approaching birth as positive. This suggest that there is no negative effect of further assessment during consultation, in case of a false-positive score on the FOBS.

In our study, about half of the sample reported a history of psychological treatment. These women were significantly more often classified as fearful on the FOBS. The etiology of FoC is likely to be multifactorial and may be related to more general anxiety proneness, as well as to specific birth related fears [Citation27]. It is therefore possible that high scores on the FOBS or W-DEQ A are not only caused by specific FoC but also by general anxiety proneness or trait anxiety. In two studies a positive association between FoC and trait anxiety was indeed found [Citation28,Citation29]. When women score above the cutoff score on the FOBS, discussing FoC during consultation can give insight into the type of fear and what is needed to reduce or manage it better. It is important that gynecologists, midwives, and their supporting staff have the competence to identify and deal with women who have FoC or other mental health problems and that there is a good system for mental support available.

Although several questionnaires exist to identify FoC, these are more time consuming and more difficult to fill out and score than the FOBS. According to a recent review [Citation30], the FOBS is most suitable for use in clinical practice. It was rated most easy to read and understand [Citation31]. Filling in the FOBS made pregnant women think about their fear of childbirth and the specific content of their fear [Citation32]. These findings support the use of the FOBS in clinical settings as a starting point for assessment of FoC.

The second objective of this study was to examine whether screening has potential added value in identifying women above clinical consultation. As expected, women with FoC were more inclined to discuss FoC. Nevertheless, although a large portion of pregnant women indicated they had the feeling they could discuss concerns about the approaching birth, still the majority of the fearful women did not discuss FoC during consultation. This discrepancy shows that FoC can easily stay undetected. A qualitative study found that some pregnant women coped with the fear by avoiding or distancing themselves from situations that were associated with, or might heighten their fear [Citation3]. Discussing FoC can also be avoided by women because they are afraid to be seen as weak or inferior for having FoC or are afraid of not being taken seriously [Citation3,Citation33]. Detecting FoC is relevant, as it can be effectively treated with interventions like cognitive therapy and group psycho-education combined with relaxation [Citation34], leading to more confidence in the delivery, increased wellbeing during pregnancy, more positive birthing experiences and fewer postnatal depressive symptoms [Citation34–39]. Thus, it is important that the caregivers standardly initiate the subject of FoC.

We found that women with FoC were more likely to experience the discussion of FoC as neutral or dissatisfying than women without FoC. As seen in other studies, this can be caused by an intensification of fear during conversation, because it can trigger self-doubt, feelings of inferiority, uncertainty and fear of being neglected or dismissed in their feelings [Citation3,Citation33]. In previous qualitative research, women mentioned that an interested, understanding and judgment free caregiver makes it easier to express and discuss FoC [Citation3]. Although talking about the subject can be hard at first, it can be the starting point for reducing fear and managing it better. For screening it would be beneficial to have a more uniform way of defining FoC.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the use of the W-DEQ A as a golden standard for assessing FoC as it is well validated and broadly used. Furthermore, we asked participants if they talked about FoC with their caregiver, which gave insight into the added value of using a screening instrument. The sample also consisted of a large group of nulliparous women.

This study also has some limitations. The way participants were recruited could have influenced the selection of the sample, by excluding women without internet and potentially selecting more highly educated women. The sample indeed consisted of relatively highly educated women, not representative for the educational level of the general Dutch female population. However, in our study, no significant correlation was found between educational level and FOC assessed with the FOBS. In our study, we did not register how women were recruited and therefore could not determine if the prevalence rates of FOC differed.

Conclusion

This study contributed to validation of the Dutch FOBS and underlines the need for screening and discussing FoC in clinical practice.

Disclosure statement

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Bewley S, Cockburn J. Responding to fear of childbirth. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2128–2129.

- Demšar K, Svetina M, Verdenik I, et al. Tokophobia (fear of childbirth): prevalence and risk factors. J Perinat Med. 2018;46(2):151–154.

- Eriksson C, Jansson L, Hamberg K. Women's experiences of intense fear related to childbirth investigated in a Swedish qualitative study. Midwifery. 2006;22(3):240–248.

- O'Connell MA, Leahy-Warren P, Khashan AS, et al. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(8):907–920.

- Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, et al. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):28.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Halmesmäki E, et al. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG. 2009;116(1):67–73.

- Deklava L, Lubina K, Circenis K, et al. Causes of anxiety during pregnancy. Proc – Soc Behav Sci. 2015;205:623–626. ISSN 1877-0428,.

- Dencker A, Nilsson C, Begley C, et al. Causes and outcomes in studies of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2019;32(2):99–111.

- Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, et al. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: a risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20(3):189–209.

- Adams SS, Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A. Fear of childbirth and duration of labour: a study of 2206 women with intended vaginal delivery. BJOG. 2012;119(10):1238–1246.

- Zaers S, Waschke M, Ehlert U. Depressive symptoms and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29(1):61–71.

- Shlomi Polachek I, Dulitzky M, Margolis-Dorfman L, et al. A simple model for prediction postpartum PTSD in high-risk pregnancies. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(3):483–490.

- O'Connell MA, Leahy-Warren P, Kenny LC, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with severe fear of childbirth. J Psychosom Res. 2019;120:105–109.

- Wijma K, Wijma B, Zar M. Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19(2):84–97.

- Calderani E, Giardinelli L, Scannerini S, et al. Tocophobia in the DSM-5 era: outcomes of a new cut-off analysis of the Wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire based on clinical presentation. J Psychosom Res. 2019;116:37–43.

- Haines HM, Pallant JF, Fenwick J, et al. Identifying women who are afraid of giving birth: a comparison of the fear of birth scale with the W-DEQ a in a large Australian cohort. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(4):204–210.

- Roosevelt L, Low LK. Exploring fear of childbirth in the United States through a qualitative assessment of the Wijma delivery expectancy questionnaire. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45(1):28–38.

- Haines H, Pallant JF, Karlström A, et al. Cross-cultural comparison of levels of childbirth-related fear in an Australian and Swedish sample. Midwifery. 2011;27(4):560–567.

- van Dinter-Douma EE, de Vries NE, Aarts-Greven M, et al. Screening for trauma and anxiety recognition: knowledge, management and attitudes amongst gynecologists regarding women with fear of childbirth and postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33(16):2759–2767.

- Castor EDC. Castor Electronic Data Capture. 2019.

- Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Karlström A, et al. Exploring the fear of birth scale in a mixed population of women of childbearing age – a Swedish pilot study. Women Birth. 2018;31(5):407–413.

- IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 24.0. Armonk (NY): IBM Corp.; 2016.

- https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/levensloop/kinderen-krijgen.

- https://assets.perined.nl/docs/aeb10614-08b4-4a1c-9045-8af8a2df5c16.pdf.

- https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2019/10/evenveel-vrouwen-als-mannen-met-hbo-of-wo-diploma.

- https://www.trimbos.nl/docs/71379d1f-7622-4925-8550-b9e9c7e483d8.pdf.

- Klabbers G, Heuvel MMA, Bakel H, et al. Severe fear of childbirth: its features, assessment, prevalence, determinants, consequences and possible treatments. Psychol Top. 2016;25:107–127.

- Jokić-Begić N, Zigić L, Nakić Radoš S. Anxiety and anxiety sensitivity as predictors of fear of childbirth: different patterns for nulliparous and parous women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;35(1):22–28.

- Alipour Z, Lamyian M, Hajizadeh E, et al. The association between antenatal anxiety and fear of childbirth in nulliparous women: a prospective study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011;16(2):169–173.

- Richens Y, Smith DM, Lavender DT. Fear of birth in clinical practice: a structured review of current measurement tools. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018;16:98–112.

- Slade P, Balling K, Sheen K, et al. Identifying fear of childbirth in a UK population: qualitative examination of the clarity and acceptability of existing measurement tools in a small UK sample. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):553.

- Ternström E, Hildingsson I, Haines H, et al. Pregnant women's thoughts when assessing fear of birth on the Fear of Birth Scale. Women Birth. 2016;29(3):e44–e49.

- Nilsson C, Lundgren I. Women's lived experience of fear of childbirth. Midwifery. 2009;25(2):e1–e9.

- Striebich S, Mattern E, Ayerle GM. Support for pregnant women identified with fear of childbirth (FOC)/tokophobia – a systematic review of approaches and interventions. Midwifery. 2018;61:97–115.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, et al. Obstetric outcome after intervention for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women – randomised trial. BJOG. 2013;120(1):75–84.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, et al. Group psychoeducation with relaxation for severe fear of childbirth improves maternal adjustment and childbirth experience – a randomised controlled trial. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;36(1):1–9.

- Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, et al. Life satisfaction, general well-being and costs of treatment for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women by psychoeducative group or conventional care attendance. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(5):527–533.

- Toohill J, Fenwick J, Gamble J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a psycho-education intervention by midwives in reducing childbirth fear in pregnant women. Birth. 2014;41(4):384–394.

- Nieminen K, Berg I, Frankenstein K, et al. Internet-provided cognitive behaviour therapy of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth – a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2016;45(4):287–306.