Abstract

Introduction: Unintended pregnancies are a worldwide health issue, faced each year by one in 16 people, and experienced in various ways. In this study we focus on unintended pregnancies that are, at some point, experienced as unwanted because they present the pregnant person with a decision to continue or terminate the pregnancy. The aim of this study is to learn more about the decision-making process, as there is a lack of insights into how people with an unintended pregnancy reach a decision. This is caused by 1) assumptions of rationality in reproductive autonomy and decision-making, 2) the focus on pregnancy outcomes, e.g. decision-certainty and reasons and, 3) the focus on abortion in existing research, excluding 40% of people with an unintended pregnancy who continue the pregnancy. Method: We conducted a narrative literature review to examine what is known about the decision-making process and aim to provide a deeper understanding of how persons with unintended pregnancy come to a decision.Results: Our analysis demonstrates that the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy consists of navigating entangled layers, rather than weighing separable elements or factors. The layers that are navigated are both internal and external to the person, in which a ‘sense of knowing’ is essential in the decision-making process. Conclusion: The layers involved and complexity of the decision-making regarding unintended pregnancy show that a rational decision-making frame is inadequate and a more holistic frame is needed to capture this dynamic and personal experience.

Introduction

Unintended pregnancies are a worldwide health issue, faced each year by one in every 16 people who can become pregnant [Citation1, Citation2]. They can have an impact on the mental health of pregnant persons as it can cause shock and stress when the pregnancy is discovered and psychosomatic complaints during the decision-making process and after the pregnancy [Citation1, Citation3, Citation4].

Unintended pregnancies are pregnancies that are mistimed, occurring too soon, or were not intended at any time [Citation5, Citation6]. They refer to pregnancies that were not planned or intended, focussing on the intentions and behavior of the person becoming pregnant and providing information about the situation in which the pregnancy occurs [Citation7]. Defining a pregnancy as unintended, does not provide information about how this pregnancy is experienced as wanted or unwanted, which is not a static experience but can change over time and across circumstances [Citation5, Citation8]. It can also include strong feelings of ambivalence toward the pregnancy. There are unintended pregnancies that are experienced as wanted at the point of discovery, making it a nice surprise and no decision-making is required. Feelings of unwantedness can occur at discovery but can also develop later in the unintended pregnancy. At whichever moment they start it means that the pregnant person has to work through these feelings and come to a decision about the pregnancy. Those persons with an unintended pregnancy that experience their pregnancy as unwanted at discovery, can immediately decide that they want to terminate the pregnancy [Citation9]. Even though this process is brief, it a decision-making process none the less.

In this study we focus on unintended pregnancies that are experienced as unwanted at some point during the pregnancy because we want to focus on persons with an unintended pregnancy that are faced with a decision to terminate the pregnancy or continue the pregnancy and raise the child or to relinquish the child for adoption. Most pregnant people (60%) live in a country where—as is the case in the Netherlands—they can choose to either terminate or carry out the pregnancy [Citation10]. Research shows that making a decision about an unintended pregnancy can be difficult, stressful and can have long-lasting impact [Citation3, Citation11]. Reaching a decision can be experienced as a relief, and it is important for a person with an unintended pregnancy to make their own decision; the more it is their own choice the better they can move forward and integrate it in their life story [Citation12, Citation13].

To be able to support people with an unintended pregnancy in reaching their own well-informed decision, we need to learn more about the decision-making process. With this study we want to contribute to creating more knowledge about this very personal process, as there is a lack of current insights into how people with an unintended pregnancy come to a decision. Firstly, this is because reproductive decision-making is framed within the context of reproductive autonomy. This means that people can freely decide about their bodies and reproductive matters, having individual rights, autonomous decision and rational choice at its core [Citation2, Citation14]. Persons are expected to map out their intentions, plan if and when they want to conceive and behave according their intentions and plan [Citation5]. This approach has narrowed the scope of research into these decision-making processes by putting the focus on rational choice and planned behavior [Citation6]. According to the model of rational decision-making, people are capable of reaching a rational decision by assessing all the information and choosing the best option for them [Citation15]. This frame does not fit decision-making regarding unintended pregnancy, since this is an important life choice that is not merely rational but in which emotions, social relations and one’s own life desires also come into play. Previous research about termination of pregnancy (abortion) shows that many non-rational factors play a meaningful role in the decision-making process [Citation9, Citation11, Citation16–18]. The decision-making process transcends creating a mere list of reasons for or against the available options. Secondly, previous studies on unintended pregnancy have predominantly had a retrospective scope in which the focus lies on the outcome of the decision-making process, the reasons for the decision and the decision certainty [Citation12, Citation19]. This provides information about how people reflect on the choice they made but provides little insight into how the decision was reached. Lastly, the lack of insight into the decision-making process for all people with unintended pregnancy is due to the fact that previous research focuses primarily on people who have had an abortion [Citation9, Citation11, Citation20]. By focusing on abortion, this research disregards the approximately 40% of people who faced an unintended pregnancy but chose parenting, foster care or adoption, since worldwide only 61% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion [Citation2].

The aim of this research is to expand knowledge about the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy. We do so by analyzing existing literature on unintended pregnancy and creating an overview of what is currently known about the decision-making process of all persons with an unintended pregnancy. We intend to provide a deeper understanding of how persons with unintended pregnancy come to a decision, by focusing on their experiences and the underlying feelings and sensations that shape their decision-making process.

Method

We conducted a narrative literature review [Citation21] to examine what is known about the decision-making process of people with an unintended pregnancy. This literature review focused on the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy rather than including all that is known about unintended pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes [Citation22].

Search strategy

PsychInfo, Web of Science, Pubmed, and Google Scholar were used in the search process. Since we wanted to include information about the decision-making process of all persons with an unintended pregnancy who experienced the pregnancy as unwanted at some point, including all outcomes, the search terms “unwanted pregnancy” OR “unintended pregnancy” OR “abortion” AND “decision” were used. Because our focus lies on unintended pregnancies that were experienced as unwanted, we included both terms in our search. We also included the search term “unplanned pregnancies” as a synonym because “unplanned” falls under the definition of unintended and both terms can and are in fact alternately used to describe the same situation in which a person is pregnant and did not plan or intend to be [Citation5, Citation23, Citation24]. The term “abortion” (with the synonym “termination of pregnancy”) was included so as not to miss specific studies about this outcome, in which “unwanted” or “unintended” pregnancy is not always mentioned. Research on the option of parenting, adoption or foster care after an unintended pregnancy is included in the terms “unintended pregnancy” and “unwanted pregnancy” (and used synonym), thus additional search terms were not needed. Lastly, we used the term “decision” together with the synonym “decision-making” to capture the elements of the decision-making process in our search. By using this term, we also aim to exclude studies that focus on unintended pregnancies that were experienced as wanted and no decision-making was needed. Because we want to focus on how a decision about an unintended pregnancy is reached, we intentionally do not use the terms “outcome,” “choice” or “reason.”

Inclusion criteria

Unintended pregnancies occur throughout the world, but care facilities and options differ among countries and regions. Abortion laws and legislation also impact the options available in case of an unintended pregnancy. In order to have a choice at all, multiple options must exist. Therefore, we focused on studies performed in countries like the Netherlands where persons with an unintended pregnancy can choose to terminate a pregnancy for non-medical reasons (social indication) [Citation10]. Since we wanted to create an overview, we set the time period for publication from 2002 to 2022. Articles were included when they were written in English or Dutch and concerned the topic of unintended pregnancy and decision-making. Qualitative, quantitative, reviews and mixed method studies were included. The primary sources are articles published in peer-reviewed journals. Non-empirical articles in peer-reviewed journals without a methods section were also included as a secondary source, if they focused on the decision-making process from the pregnant person’s point of view. Lastly, we included as tertiary sources reports from national research institutes that had an impact on legislation and policy concerning unintended pregnancies. All articles included are available in full text via open access or via license of the Radboud University Library.

The first author used Rayyan, an online tool for literature reviews, to remove duplicates and indicate which articles, and for what reason, were included and excluded. The second and third author triangulated the list of included and excluded articles. During this first reading we assessed the quality of the articles by looking at the study objectives, study design, data collection and analysis, results and limitations. These elements required to check the quality of the included studies are derived from existing quality checklists for qualitative, quantitative and mixed method research [Citation25–27].

Analysis of included articles

All included articles were read in full by the first author, who collected the main findings and notes per article. The main findings were transferred to Nvivo, a program for qualitative analysis, where a first thematic analysis of the included articles was made by the first author, listing all that was mentioned about the decision-making process concerning an unintended pregnancy. The first thematic analysis, consisting of 14 themes, was discussed by all authors and further categorized into 5 clusters of themes. This second analysis was shared and discussed with fellow researchers in the field of reproductive health and their feedback was used to further shape the results and the way in which they are presented.

Results

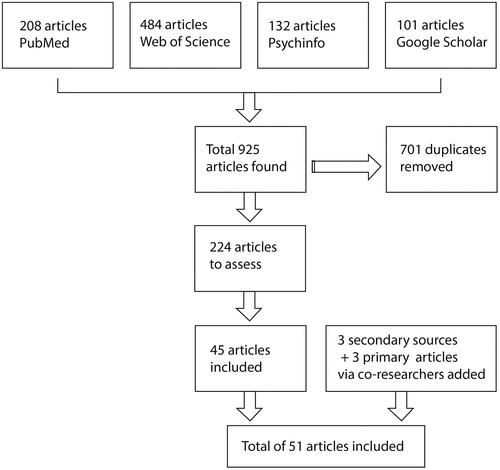

Based on the search terms used, 925 articles were found, which left 224 unique articles after duplicates were removed (see ). In total, 51 articles met the inclusion criteria and quality standards, of which 44 were a primary source, four a secondary source and three a tertiary source. The included studies were set in Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, China, England, Wales, Scotland, the United Kingdom, France, India, Iran, Mozambique, Nepal, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Spain, Sweden and the United States. All articles were identified with a number (see ).

Table 1. ID number, year of publication, authors, title, study design, location and type of source of included literature.

The majority of the included studies focus on decision-making and abortion (75%). The other included studies focus on decision-making and unintended or unwanted pregnancy, including birth and abortion as an outcome. Of the different terms “unintended” is used in 18% studies and “unwanted” in 6% of all the included studies. Despite the use of the two different terms, the meaning is the same in the included studies, both describing the situation in which a pregnant person is faced with a decision about a pregnancy that is not wanted or intended, overlapping also with the studies that focus on abortion. The term “unplanned” pregnancy is used only once in a study about termination of pregnancy. The studies have qualitative designs (37%), quantitative designs (35%), mixed method designs (14%) or a review design (14%). In only five studies (10%) the participants are still pregnant and thus in the midst of their decision-making during data collection. In all other studies information about the decision-making is collected retrospectively.

Of all studies, 12 out of 51 focus on the experience of people with decision-making about unintended (or unwanted) pregnancy and abortion. Ten studies provide insights into decision certainty and rightness. Six studies aim to specifically provide information about the decision-making process. One third (15) of the included studies look at factors that are of influence on the decision or reasons for the decision made. Eight studies focus on the context in which the decision is made or provide more theoretical insights into the decision-making process and counseling.

Even though 29% of the included studies focused on the outcome of the pregnancy, e.g. reasons or decision certainty, they also provided information about the decision-making process. By putting all the findings about the process and outcome from the literature together in our thematic analysis, and looking at them as a whole, we were able to create a dynamic view on decision-making concerning an unintended pregnancy, to which we now turn.

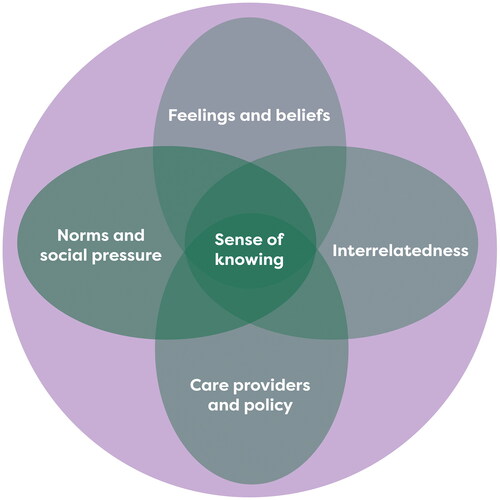

Our analysis of the included studies demonstrates that the elements involved in decision-making are strongly entangled, forming five layers and the decision-making process about an unintended pregnancy consists of navigating these entangled layers [Citation28], rather than weighing separable elements or factors (see ). The layers “sense of knowing” and “feelings and beliefs” are internal to the pregnant person and the layers “interrelatedness and context,” “care provider and policy” and “norms and social pressure” are external to the person deciding about an unintended pregnancy. In the following section, we discuss each layer separately, show how the layers impact each other and how they are navigated by the pregnant person. The numbers in parentheses in the text below refer to the study on which a finding is based. Some information about the studies is provided in the text and information about location, study design and population of all the studies can be found in .

Figure 2. Visualization of entangled layers in the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy.

Sense of knowing

Several large quantitative studies in Europe and Northern America and a global review study noted that participants knew what they wanted to do about the pregnancy, making up their minds before telling the partner or important others and before visiting a health provider (4, 6, 7, 41). These studies demonstrate how pregnant persons may be internally motivated to make a specific decision, meaning that they have an intrinsic sense of (what would be) the right decision, a sense of knowing what to do. Therefore, the innermost layer in the decision-making process is best described as a sense of knowing.

How people experience the pregnancy in their bodies is also important in the decision-making process (28) and the emerging sense of knowing what to do. Qualitative studies set in the Netherlands and Sweden show that some pregnant persons experience a strong change in their body, which can impact the way they view their pregnancy and can strengthen their sense of knowing—either about carrying out the pregnancy or terminating it (29). They may also not experience any bodily changes, and not feel pregnant, which may influence how they view the option of abortion (28). When this bodily experience contradicts the beliefs and wishes of the pregnant person, it can also cause friction between their feelings and thoughts concerning the pregnancy (29, 48)—for example, when a pregnant person has no desire to have a child right now, but has a strong bodily sense of a baby growing inside them (48). This is where sense of knowing is entangled with the feelings and beliefs of a pregnant person, the other inner layer of the decision-making process.

When looking at motives for decisions about unintended pregnancy, both qualitative and quantitative studies set in Europe, Mozambique, China and India indicate that the wish to have a child is important in the decision-making process (14, 15, 18, 21, 24, 29, 38, 43, 41, 42). A strong desire to have a child, or the lack thereof, can guide pregnant persons to their decision and add to their sense of knowing what to do. Sometimes a wish for a child, which was absent before, is discovered during the pregnancy. The pregnant person navigates through the inner layers of desires, feelings and beliefs. When desire (sense of knowing) and beliefs concerning parenthood and family contradict, it can make the decision-making process more difficult.

This sense of knowing what to do also seems to be influenced by important persons and the social context of the pregnant person, the outer layers in the decision-making process, yet is not defined by it. On the one hand, pregnant persons who have less knowledge and less (social) support feel less autonomy and certainty in reaching a decision about their pregnancy (20, 47). For example, a study in the United States where 25 young pregnant persons were interviewed shows that young persons with an unintended pregnancy generally depend more on others to decide about their pregnancy (47). They navigate toward the outer layers to come to a decision. On the other hand, a qualitative study in South Africa shows that pregnant persons who are in a repressed position due to gender inequality, who require permission from their husband or doctor, can still feel that it is their decision to make (17). Their sense of knowing what to do is strong and they can feel autonomous regardless of the context, their partner, social norms and care system (outer layers). They navigate toward their most inner layer to come to a decision.

Another example of how the sense of knowing can be impacted by important others and social norms (context) comes from another study set in South Africa. This study shows that unmarried pregnant persons experience no support for their pregnancy, which makes it very difficult to carry out the pregnancy (23). They do sense that they can make the decision autonomously and with certainty, but with limited options. Some studies describe that decision-making difficulty, or little sense of knowing what to do about an unintended pregnancy, are rooted in a general lack of autonomy, knowledge and self-efficacy. This can be related to the position of the pregnant person in society, access to reproductive health care and support from others (16, 20, 38, 39).

Feelings and beliefs

The other internal layer that a pregnant person navigates through in the decision-making progress is that of feelings and beliefs. A feeling of fear is mentioned in several studies that are set around the world to play a role in the decision-making process, causing doubt and ambivalence. There is the fear of being rejected because of the unintended pregnancy by people close to the pregnant person or in their social network (15, 21, 48). But there is also the fear of being rejected for the decision to end the pregnancy, to become a parent or to give the child up for adoption (19, 40). These fears are fed by social norms experienced by the person with the unintended pregnancy. This shows how this layer is entangled with the outer layer of social norms.

Different studies on abortion decision-making in the Netherland show there are specific fears concerning the abortion procedure but also the fear of regretting it and having mental or emotional distress afterwards (18, 29, 38). These fears cause inner conflict and can make it difficult to experience a sense of knowing. Other causes for inner conflict are also mentioned in a number of studies. Spiritual concerns and moral objections to abortion or unmarried parenting can also result in great inner conflict (19, 30) as mentioned in studies set in the United Kingdom and the United States. Pregnant persons indicate that they can feel depressed, ashamed, embarrassed and guilty for even considering terminating a pregnancy, adoption or parenting (20, 24, 27, 36). Inner conflict can also be caused by contradicting feelings regarding an unintended pregnancy (4, 9, 29, 47). These contradicting feelings toward the pregnancy, abortion and parenting, make navigating the layers of the decision-making process more difficult and may result in a person never experiencing a full sense of having made the right decision (9).

The way persons with an unintended pregnancy view their options for parenting, adoption or abortion is paramount in reaching a decision about the pregnancy. Their views are influenced by and interrelated with those of important others as well as social norms. Several interview and survey studies in Europe and Australia show that pregnant persons have strong views on what they consider to be good parenting (16, 19, 22, 26, 29). They may want to provide a child with a secure upbringing, within a loving family so that they can give the child a good life. They may want to be a good parent (for existing and future children), for which parenthood norms are influential (10, 11, 36, 41). Sometimes persons with an unintended pregnancy do not see themselves as suitable parent or partner, at this moment or ever. Wanting to be a good parent and do the right thing for the child is also influential in contemplating adoption. One mixed method study in the United States, on adoption after being denied an abortion, found that participants with an unintended pregnancy hardly considered adoption as an option because of strong views on good parenting. They did not think adoption was good for the child—they would have no knowledge of the child after the adoption and felt that they had to take responsibility (11).

Many interview and survey studies throughout the world, found that the way participants felt about abortion was of great importance when deciding about an unintended pregnancy. Pregnant persons who had a positive attitude toward abortion and saw it as a right could consider this option with a strong sense of knowing and without (inner) conflict (26). A negative attitude or view on abortion, on the other hand, did cause decision-making difficulty, navigating more toward the outer layers to come to a decision. In several studies participants indicated that they saw abortion as something shameful, the opposite of good parenting or accepted only in certain circumstances (12, 18, 19, 29, 30). One study shows that many pregnant persons contemplating ending the pregnancy felt that unintended pregnancy and abortion happen only to people who are young or careless, which made it difficult for them to consider abortion (19). One study mentioned that pregnant persons with a negative attitude toward abortion would distinguish themselves from those they deemed “careless” pregnant people in order to justify considering and/or having an abortion (18). This is another example of how feelings and beliefs about unintended pregnancy and the options available are very much influenced by partners of pregnant persons, important others and existing social norms.

Interrelatedness and context of pregnancy

The partner and important others play a crucial role in the decision-making process of persons with an unintended pregnancy. They form an important layer in the decision-making process. The relationship with the partner is mentioned both as a reason to experience the pregnancy as unintended and as a reason to contemplate terminating the pregnancy (1). Almost all included studies mention partners having a direct or indirect influence on the person deciding about their pregnancy. When a pregnant person feels supported by their partner, this is helpful in making their own decision and having a strong sense of knowing what to do with the pregnancy (47, 48, 51). Studies that looked at the decision-making process from both partners’ perspectives found that feelings of autonomy and decisiveness can be interconnected (13). When the pregnant person felt very decisive, the partner also felt more certain in the decision-making process. However, when the partner had more doubts, the pregnant person also felt less decisive and more conflicted.

The stability and safety of the relationship with the partner and potential co-parent of a child is also named in great number of qualitative studies in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia and North America as being of great importance (14, 17, 21, 24, 26, 29, 36–38, 43, 50). Pregnant persons with new, unstable or unsafe relationships were often reluctant to have a child come into this situation.

In addition to the lack of partner support, the lack of support from important others such as family and friends can also influence the pregnant person’s decision, as shown in a global review study and interview studies in Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States (4, 5, 14, 16, 19). This lack of support may stem from differing views on the pregnancy and desired outcome and can make it more difficult for the pregnant person to trust their sense of knowing and their ability make an autonomous decision (15, 22, 23). These strong external voices of important others can even create a sense of pressure to make a certain decision about the pregnancy (13, 29, 30, 38, 41). This puts a focus on the outer layers of the decision-making process and makes it more difficult for a pregnant person to really experience their sense of knowing, feelings and beliefs. Lack of support does not inhibit the pregnant person to come to a decision in the end, but it does make them feel more alone and more ashamed (17, 24, 32).

As described before, the layer of interrelatedness and context of the pregnancy is strongly entangled with the layer of feelings and beliefs in the decision-making process, as is shown in several of the included studies about abortion. Some pregnant persons want to grow before having children, both emotionally but also in their career and financial independence. In several qualitative studies participants indicated that they did not feel ready to have a child and did not consider themself suited to parent at this point in their life or ever (4, 9–11, 14, 15, 22, 26, 39, 41, 42, 48), sometimes because of (mental) health issues (15, 17, 22, 24, 43). These pregnant persons have another vision for their life, they feel the context is not (yet) right. This is where the layers are very much entangled and a pregnant persons can both feel the need for another path and indicate that they do not have the right setting (living conditions, work, school, finances) to have a (or another) child (3, 5, 9, 17, 20, 21, 24, 29, 37, 38, 43, 47). In all studies where this is mentioned, set throughout the world, it is stated as a mix of both feelings and practical reasons.

Care providers and policy

A number of both qualitative and quantitative studies mention the role and influence of the professional care provider in the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy. Even though they are part of the context, these providers form a distinct layer in the decision-making process, one, however, that is not always explicitly part of the process. Studies describe various ways in navigating this layer. First, there is a group of people who come to a decision without needing help from a care provider. The care provider plays no role in the decision-making process, other than providing a referral to a clinic when needed (10). The second situation is when a pregnant person does seek the help of a care provider for information about their options and counseling. The experiences in this situation are mixed: some pregnant persons indicate that it was helpful and adequate, while others would have wanted more support, information and care from their care provider (3, 7, 16, 27, 31, 33, 43). In this case, the influence of the care provider can be either positive or negative in helping to come to a decision about the pregnancy. In the last scenario, care providers have an overpowering influence on the decision-making process. For example, in an interview study on access and availability of abortion services in Mozambique, pregnant persons depended on their doctor as they had to approve the abortion and decide on the procedure to be followed (15).

In addition to care providers, the care system is also part of this layer in the decision-making process. Only two included studies, one a global review and the other a large survey in the United States, considered policies regarding abortion care in regard to decision-making (45, 46). These studies conclude that mandatory waiting time and counseling do not increase decision certainty when choosing abortion. In the other studies included in this review, policies concerning reproductive care and abortion care were hardly mentioned as either helpful or hindering in the decision-making process of persons with an unintended pregnancy.

Norms and social pressure

As mentioned in the description of the previous layers, the social norms are entangled with all the layers of the decision-making process. Social norms are mentioned in all of the included studies to be of influence on the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy. Pregnant persons experience outspoken ideas about unintended pregnancy and abortion in their social surroundings, from within themselves (normative beliefs), but also from important others and general attitudes that are present in their social context. These norms vary depending on the age of the pregnant person. For example, young pregnant persons, under 25 years old, interviewed in a Swedish study indicate that becoming a parent at a young age is seen as negative and receives little support. They perceived this negative attitude as pressure to end the pregnancy (5, 20). On the other hand, a small interview study in the United States shows that older pregnant persons (25–30 years and older) are faced with the attitude that they should take responsibility for their actions and should choose parenting (12). A large survey study on stigma and decision-making about unintended pregnancy found that persons with an unintended pregnancy who experienced more stigma had more difficulty reaching a decision (35). This indicates an entanglement of social norms with both the inner and outer layers of the decision-making process. In all cases, regardless of age, persons with an unintended pregnancy are blamed for becoming pregnant, which makes them feel ashamed (12, 24). They want to do what is seen as right by social norms, which is difficult as both parenting and abortion are judged. Gender norms are at the base of this, because they frame the way societies and pregnant persons themselves look at pregnancy and parenthood (36).

It can be difficult to break with social norms and make a decision that contradicts these. Even when pregnant persons have a strong sense of knowing what to decide, they may still feel the pressure of social norms and other people’s attitudes. For example, research in Great Britain shows that pregnant persons who visit an abortion clinic and are faced with abortion protestors find this intimidating, intrusive and even threatening (8). It does not make them change their mind about their decision, but it does make them feel like they are doing something that is perceived as wrong.

Discussion

Conclusion

Decision-making regarding an unintended pregnancy is a complex process in which internal and external layers are entangled [Citation28]. Even personal or inner layers, such as one’s sense of knowing, feelings and beliefs, cannot be detached from and are still impacted by the external layers of interrelatedness to others, the care setting and social norms. The layers involved and complexity of the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy show that a rational decision-making frame is inadequate to capture this process and a more holistic frame is needed to capture this dynamic and personal experience.

Interpretations

From our analysis we learn that a sense of knowing what to do is vital for people to be able to make their own decision about an unintended pregnancy. This sense comes from within the person and can work as a compass to guide them through the decision-making process. In the literature, this sense of knowing is also often described as (a sense of) autonomy. It is mentioned as important in the decision-making process, both as helpful when it is strong, and as a reason for decision difficulty when it is lacking. It seems that this sense of knowing or autonomy can be strong even when the pregnant person is in a restricted situation or dependent on others when deciding about the pregnancy. Autonomy can be conceptualized in different ways [Citation29], and it is unclear in the included studies how autonomy and thus a sense of knowing is defined. Further research is needed to gain more insight into this sense of knowing or autonomy as a concept and as a layer in the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy.

In addition to the sense of knowing, it is clear that the partner is of great importance to the pregnant person’s decision [Citation30, Citation31]. It is not a shared decision, as the pregnant person is presumably the final decision-maker, but the pregnant person often is very connected to the partner involved and their ideas and wishes regarding the pregnancy. The partner is vital in the layer of “interrelatedness,” which is entangled with the inner layers of “sense of knowing” and “feelings and beliefs” as well as the outer layers.

Most research included in our study focused on the outcome of the pregnancy, reasons for the decision and decision certainty from a retrospective perspective. Even in those studies in which the pregnant person was still deciding, the focus was on the reasons for either parenting or abortion, with less emphasis on the process of reaching a decision. These studies showed that invariably more than one reason was given for a decision about the pregnancy, and that even practical reasons stem from non-rational elements. For example, a lack of financial means, small housing, wanting to finish school, all come from a desire to be a good parent, a good partner and a stable and responsible person.

The decision regarding unintended pregnancy is clearly much more complex than making a list of pros and cons per option. It is a complex inner process that takes place within the pregnant person. It is valuable to discover more about this inner process, how the inner and external layers are entangled and what this inner process looks like. Since a rational frame is inadequate to capture this process, there is a need to explore other theories about decision-making. Anthropologists look at decision making from the perspective of the social context and focus on the important others and the social norms when making a decision [Citation32, Citation33]. The importance of others in the decision-making process is supported by care ethics [Citation34–36]. According to their theory of shared decision-making it is vital to actively include others in the decision-making process about care related issues. In both these theories the focus lay more on others and the context, which does not grasp the inner complex process of making a decision about an unintended pregnancy. A wider search for a framework on decision-making is therefore warranted. In a subsequent empirical inquiry into the layered and complex decision-making process about unintended pregnancy, we will use a Dialogical Self approach to shed more light on this inner process and to explore its adequacy [Citation37].

In this study we choose to focus on unintended pregnancies that were experienced as unwanted at some point and for which decision-making was needed. We use the term “unintended pregnancy” and included “unwanted pregnancy” in our search. The literature shows that, even though “unintended” was most often used, both “unintended” and “unwanted” are used to describe the situation in which a pregnant person is faced with a decision about a pregnancy that was not intended or planned. This confirms the focus on intention when defining a pregnancy and the difficulty to catch the fluid experience of the pregnancy in language. It would help to expand the research on how women describe their pregnancy so that the discourse fits their experience and to rethink the pregnancy intention and planning paradigm [Citation5, Citation6, Citation24].

Our last takeaway is the lack of inclusivity in the language used in research on unintended pregnancy. In almost all studies included, the respondents were referred to as “women” without it being clear if they identified as such. Terms like “a good mother” or “maternal feelings” were used frequently. This is language used by both the respondents and researchers involved, but it does make it clear that language concerning pregnancy is exclusive. It is a vital point to take with us as we conduct further research about the decision-making process concerning an unintended pregnancy.

Methodological reflection

In this literature study we focused on studies conducted in countries where abortion is legally possible. We can therefore not say whether the decision-making process about an unintended pregnancy is different when the option of abortion is not available. The study comparing narratives about decision-making in South Africa (where legal abortion is available) and Zimbabwe (where abortion is illegal) (36) indicates that these processes are very similar. However, more research is needed. Even though we focused on studies in countries where abortion for non-medical reasons was possible, the variety of legislation and practice can still differ. Looking at the Unites States alone gives an indication of the differences that occur in availability and access to abortion services, which can influence the decision-making process regarding unintended pregnancy. Our aim was to focus on the decision-making process and not on the outcome of the decision. We have therefore not compared the decision-making process per outcome, making it impossible to make statements on whether and how these processes might differ between pregnant persons who carried out the pregnancy and those who terminated the pregnancy. The literature search was conducted in August-October 2022, limiting the inclusion of articles to that date, with the possibility of missing more recent literature on the subject.

Authors’ contributions

Dalmijn: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization Visse: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision van Nistelrooij: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the “Concerning Maternity” research network, for providing their thoughts and feedback on the initial analysis, helping to shape the findings and results of the review.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interest to declare.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abajobir AA, Maravilla JC, Alati R, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression. J Affective Disord. 2016;192:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.008

- Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet. 2020;8:e1152–e61.

- Dijkstra CI, Dalmijn EW, Bolt SH, et al. Women with unwanted pregnancies, their psychosocial problems, and contraceptive use in primary care in Northern Netherlands: insights from a primary care registry database. Fam Pract. 2023;40(5–6):648–654. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmad036

- van Brouwershaven AC, Dijkstra CI, Bolt SH, et al. Discovering a pregnancy after 30 weeks: a qualitative study on explanations for unperceived pregnancy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2023;44(1):2197139. doi:10.1080/0167482X.2023.2197139

- Aiken ARA, Borrero S, Callegari LS, et al. Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspect Sexual Reprod Health. 2016;48:147. doi:10.1363/48e10316

- Auerbach SL, Coleman-Minahan K, Alspaugh A, et al. Critiquing the unintended pregnancy framework. J Midwif Women’s Health. 2023;68:170–178. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13457

- Sprenger M, Beumer WY, van Ditzhuijzen J, et al. 2023. Psychometric properties of the dutch london measure of unplanned pregnancy for pregnant people and their partners. medRxiv: 2023.11.13.23298453.

- Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield Timajchy K, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(2):94–101. doi:10.1363/3509403

- Brauer M, van Nijnatten C, Vollebergh WA. 2012. Besluitvorming rondom ongewenste zwangerschap. Een kwalitatief onderzoek onder vrouwen die tot een abortus hebben besloten en vrouwen die tot het uitdragen van hun zwangerschap hebben besloten. Utrecht: Universiteit van Utrecht.

- Centre for Reproductive Rights. 2023. ‘The World’s Abortion Laws’. https://reproductiverights.org/maps/worlds-abortion-laws/.

- Brauer M, van Ditzhuijzen J, Boeije H, et al. Understanding decision-making and decision difficulty in women With an unintended pregnancy in The Netherlands. Qual Health Res. 2019;29:1084–1095. doi:10.1177/1049732318810435

- Rowland BB, Rocca CH, Ralph LJ. Certainty and intention in pregnancy decision-making: an exploratory study. Contraception. 2021;103(2):80–85. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.11.003

- van der Heij A. Besluitvorming bij ongewenste zwangerschap en online hulp bij abortusverwerking. Twee bronnen voor nieuw perspectief op preventie van psychosociale klachten na abortus. Tijdschrift Voor Seksuologie. 2017;41:127–232.

- Van der Sijpt E. 2014. Complexities and contingencies conceptualised: towards a model of reproductive navigation. From Health Behaviours to Health Practices 120–31.

- Tiemeijer WL. 2011. Hoe mensen keuzes maken. De psychologie van het beslissen. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

- Fiom. 2020. “Factsheet online module ‘Zwanger, wat nu?’ 2015-2019.”

- Ueno Y, Mitsuko O, Kako M, et al. Shared desicion making for women facing an unplanned pregnancy: a qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22(4):1186–1196. doi:10.1111/nhs.12791

- Elizalde S, Mateo N. Young women: between the "green tide" and the decision to have an abortion]. Salud Colect. 2018;14(3):433–446. doi:10.18294/sc.2018.2026

- Jovel I, Cartwright A, Ralph L, et al. Understanding decision certainly AMONG women searching online FOR abortion care. Contraception. 2019;100:316–316.

- van Ditzhuijzen J, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, et al. The impact of psychiatric history on women’s pre- and postabortion experiences. Contraception. 2015;92(3):246–253. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.05.003

- Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writing. 2015;24(4):230–235. doi:10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

- Jordan Z, Lockwood C, Munn Z, et al. The updated joanne briggs institute model of Evidence-Based healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018;16(4):227–241. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000139

- Moreau C, Bohet A, Le Guen M, et al. Unplanned or unwanted? A randomized study of national estimates of pregnancy intentions. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(6):1663–1670. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.011

- Helfferich C, Hessling A, Klindworth H, et al. 2014. Unintended pregnancy in the life-course perspective. Adv Life Course Res 21:74–86. doi:10.1016/j.alcr.2014.04.002

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated critera for reporting qualitative research (COREQ); a 32-item checlist for interviews and focusgroups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting obersvational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(11):867–872. doi:10.2471/blt.07.045120

- Page M, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

- Luna F. Identifying and evaluating layers of vulnerability - a way forward. Dev World Bioeth. 2018;19(2):86–95. doi:10.1111/dewb.12206

- Ahlin Marceta J. A non-ideal authenticity-based conceptualization of personal autonomy. Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22:387–395. doi:10.1007/s11019-018-9879-1

- Chibber KS, Biggs MA, Roberts SC, et al. The role of intimate partners in women’s reasons for seeking abortion. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:e131-8. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.007

- Kirkman M, Rowe H, Hardiman A, et al. Reasons women give for abortion; a review of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12(6):365–378. doi:10.1007/s00737-009-0084-3

- Boholm Å, Henning A, Krzyworzeka A. Anthropology and decision making: an introduction. Focaal. 2013;2013(65):97–113. doi:10.3167/fcl.2013.650109

- Bruch. Decision-Making processes in social contexts. Annu Rev Sociol. 2017;43:207–227. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053622

- Olthuis G, Leget C, Grypdonck M. Shared decision making needs a care perspective. BMJ. 2012;345(v06 15):e7419–e7419. doi:10.1136/bmj.e7419

- van Nistelrooij I, Visse M, Spekkink A, et al. How shared is shared decision-making? A care-ethical view on the role of partner and family. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(9):637–644. doi:10.1136/medethics-2016-103791

- van Nistelrooij I, van der Waal R. Moederschap en geboorte: relationaliteit als alternatieve ethische benadering. Tijdschrift Voor Gezondheidszorg En Ethiek. 2019;29:53–57.

- Hermans HJM. Self as a society of I positions: a dialogical approach to counseling. J Hum Counsel. 2014;53(2):134–159. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2014.00054.x