Abstract

Problem, research strategy, and findings

Digital platforms have transformed housing practices and enabled new markets to emerge. Here we report on a study in which we examined these practices and their implications for planning, focusing particularly on low-cost and informal rental accommodation. With reference to Australia’s three largest cities (Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane), we investigated the range and scale of accommodation types advertised on major commercial and peer-to-peer platforms Realestate.com.au, Flatmates.com.au, Gumtree.com.au, and Airbnb.com, identifying an informal housing typology comprising secondary dwelling units, share homes or rooms, and Airbnb-style holiday accommodation, much of which violates local regulation. We found that secondary dwellings and other irregular types of accommodation comprised more than 3% of Sydney’s rental vacancies and more than 10% of enumerated rental vacancies in Brisbane during the study period of August 2021. Informal tenures such as rooms in share homes or negotiated arrangements offered by property owners extended rental supply in Sydney and Melbourne by the equivalent of more than 16% over the same period, rising to almost 34% in Brisbane. These findings show that platforms have enabled property owners to market illegal rentals and unauthorized dwellings but also have helped lower-income earners access lower-cost accommodations. Planners must determine which practices support affordability without generating unacceptable risks for residents and neighborhoods.

Takeaway for practice

Platforms have enabled landlords to market informal and illegal rental accommodation while evading regulatory oversight. Using data exposed on these platforms, our study shows the important role played by this sector in serving lower-income renters but also the risks for tenants occupying substandard units or precarious tenures. Planners must address these risks in supporting diverse rental supply.

The rise of online platforms offering residential real estate and services has transformed how housing is marketed, accessed, and used (Boeing & Waddell, Citation2017; Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2022; Fields & Rogers, Citation2021). Yet despite the wave of attention that platforms such as Airbnb have attracted (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2018; Wachsmuth & Weisler, Citation2018), planners have been slower to consider broader implications for local housing markets and neighborhoods arising from online platforms and the practices they enable. We investigated this theme by looking at different types of rental accommodation listings being marketed online and focusing particularly on lower-cost and/or informal housing. In this context, informal housing includes residential tenures (such as negotiated agreements between tenants and landlords or between residents sharing a rental property together) and/or accommodation types (such as secondary units, unauthorized dwellings, boarding houses) that avoid or fail standard regulatory requirements (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017; Harris, Citation2018). With reference to a novel data set comprising more than 60,000 rental listings advertised in Australia’s dominant metropolitan housing markets, we constructed a typology of low-cost and informal dwelling and tenure types to examine intersections with local planning frameworks and housing markets. In so doing, we sought to inform wider research on the implications of digital platforms for housing practices, planning, and urban governance (Porter et al., Citation2019). Our findings show how digital platforms both enabled and revealed a range of informal rental practices that collectively amounted to the equivalent of a significant 20% to 40% of the rental vacancy rate across Australia’s three largest cities. However, although we found that rents were typically below the formal market, they were not necessarily sustainable for low-income households, who must also accept lower levels of tenure security and or privacy or amenity. Overall, our findings highlight the complex and changing intersections between digital platforms and housing markets, which raise new challenges for planners seeking to encourage and preserve affordable rental accommodation.

First, we give an overview of the literature on platformization and the range of informal practices now facilitated and exposed by digital platforms within a wider setting of housing financialization and unmet housing need. Although informal housing practices have long been examined by researchers in the so-called Global South, our study joins the small but growing literature on platform-enabled informality in advantaged so-called Global North regions such as Australia (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2021; Shrestha et al., Citation2021). We then introduce the Australian case study cities and outline our research methods and data sources. Third, we present key findings across the different housing platforms and cities, constructing a typology of informal dwellings and tenures. In doing so, we highlight the intersections of these informal housing typologies with planning policies and rules designed to manage risks or support informal dwelling typologies. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for understanding and planning for digitally mediated informal rental practices.

Online Platforms and the Housing System

Online platforms have increasingly come to dominate interactions across the housing market as with many other aspects of our lives. Their pervasiveness reflects the extraordinary advances in information and communications technologies that have contributed to global financialization and the rise of platform capitalism, whereby oligarchical firms profit by connecting people and the data on which these networks depend and produce (Srnicek, Citation2017). Most searches for homes to rent or buy are now performed online, bringing powerful geospatial technology to connect sellers and buyers in rapid and efficient ways (Rae, Citation2015). In the analog era, obtaining accurate information about the housing market—the availability, characteristics, and price of potential homes—was limited by the logistics of searching within a particular geographical area and obtaining reliable data about comparable options. Contemporary platforms for buying and renting real estate make these searches almost frictionless (Boeing et al., Citation2021). They form part of the wider platform real estate ecosystem for digitally marketing, managing, and investing in property also known as Prop Tech (property technology; Fields & Rogers, Citation2021).

By increasing access to market-relevant information about the range of potential choices, online real estate platforms and the data they provide should in theory make residential searches fairer for those seeking to purchase or rent, while promoting more efficient use of the housing stock and opening new, real-time insights for policymakers (Rae, Citation2015). However, over time it has become apparent that online platforms tend to reproduce and even reinforce traditional power imbalances and information asymmetries in the housing market (Boeing et al., Citation2021). These imbalances reflect real-world sociospatial differences and sorting. For instance, an analysis of Craigslist advertisements in the United States found differences in the quantity and type of information relating to census tract communities that were “whiter, wealthier, and better-educated” than those applying to “less-white” or lower-income areas (Boeing et al., Citation2021, p. 122). Platforms also enable landlords to use big data algorithms to screen out potential tenants based on unstated criteria and/or to offer differential rental terms (Wainwright, Citation2022). Similarly, those advertising residential real estate can provide misleading information to attract potential buyers or tenants (Harten et al., Citation2021). Separated from the services they enable, platforms avoid accountability for the quality of information they disseminate, leaving those with limited knowledge of the housing market vulnerable to exploitation (Nasreen & Ruming, Citation2022). Such risks are amplified within informal and marginal sectors of the housing market, where providers can use platforms to reach a broader market of low-income tenants while bypassing rental regulations or building rules. Termed “digital informalisation” by scholars Ferreri and Sanyal (Citation2022), the range of accommodation enabled and marketed by short- and long-term rental platforms sits beyond the “formal regulations of the state” to “create forms of digital informality hitherto unstudied within the so called global north context” (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2022, p. 1036).

Digital Informality, Unmet Housing Need, and Planning

Consistent with the definition established by Harris (Citation2018) in his global survey of informal urban development, we defined informal housing as dwellings or rental tenures that contravene the laws of the state or deny occupants full protection under these rules. This may include a range of housing practices, from offering rooms in shared houses to irregular or substandard rental dwellings or unauthorized short-term accommodation. No longer considered solely a Global South phenomenon, these practices are occurring worldwide, facilitated and enabled by Prop Tech platforms offering residential real estate as well as specialized websites advertising share housing or Airbnb-style tourist accommodation.

Informal housing practices are not simply online marketing of residential real estate, nor are they simple expressions of rental precarity. Many renters in the Global North remain within the formal housing sector, despite high costs and the risk of eviction. However, the wider pressures associated with the financialization of housing and retrenchment of the welfare state (Rolnik, Citation2013) help explain why a market for alternative tenures and substandard rental accommodation may arise (Maalsen et al., Citation2022; Parkinson et al., Citation2018; Ronald et al., Citation2023). Further, those engaging in informal housing practices are not always economically disadvantaged (Chiodelli et al., Citation2021). For example, landlords may seek to maximize returns via the short-term rental market by marketing their properties to tourists via Airbnb-style platforms or by adding a secondary dwelling, capitalizing on the unmet demand for affordable rental accommodation.

Thus, informality is a global phenomenon that manifests differently in different contexts (Chiodelli et al., Citation2021), with close intersections between formal and informal sectors (Roy, Citation2005). The state establishes formal systems of authority and law, thereby defining the range of informal activities that occur within and beyond the formal sector (Devlin, Citation2018; Harris, Citation2018). State actions to enforce these rules or to tolerate infractions—for instance, by turning a blind eye to irregular residential construction, unlawful dwellings, or illegal rental practices—establish the settings in which informal housing practices emerge (Gurran et al., Citation2021). The rise of global platforms such as Airbnb has further complicated state enforcement efforts because of the online virtual transactions they enable (Gurran & Sadowski, Citation2019).

States have sought to formalize irregular housing typologies by reducing regulatory requirements through zoning or code reforms. These approaches involve the state tolerating or even explicitly enabling informal models instead of directly providing affordable housing (Harris, Citation2018). More widely they reflect a political preference for encouraging market-based responses to housing need (Wetzstein, Citation2022). Examples include initiatives to encourage secondary dwellings such as basement suites and laneway houses in Vancouver (Mendez, Citation2017; Mendez & Quastel, Citation2015) or accessory units in the United States (Anacker & Niedt, Citation2023; Wegmann & Chapple, Citation2014). Similarly, new single-room occupancy boarding houses or so-called co-housing projects featuring shared kitchens and/or recreation areas are emerging in parts of Europe (Ronald et al., Citation2023) and Australia (Gurran et al., Citation2021), targeting students or lower-income renters. Unlike more longstanding types of co-housing that are self-organized by residents who choose to live together in an intentional community (Chiodelli & Baglione, Citation2014), these new developments are produced by speculative private developers. Overall, policymakers may welcome these initiatives as an important contribution to lower-priced rental supply. Planners may seek to encourage new developments of this type or address health and safety risks associated with unregulated and unlawful accommodation by ensuring that zoning laws explicitly permit smaller and diverse units within existing residential properties and neighborhoods (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017).

In summary, informal housing markets may respond to wider conditions of rental precarity but should be understood as a distinct set of activities. They may be the outcomes of deliberate state efforts to liberalize and enable alternative dwelling types and tenancy arrangements or to selectively ignore infractions. Digital platforms in turn support informal rental practices by connecting landlords and share households with potential tenants and by providing cover for informal economic activities via virtual transactions able to occur beyond regulatory oversight. These same platforms also offer a window into hidden sectors of the rental market that have hitherto been poorly understood. Thus, platforms raise both opportunities and challenges for local planners and enforcement officers concerned about the quality and safety of rental accommodation and new housing construction.

Platforms and Informal Housing in Australia: Context and Study Design

To investigate the range of informal housing practices being marketed via online platforms in Australia, we focused on rental listings advertised on real estate platforms across Australia’s three largest and most unaffordable cities: Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane. Sydney and Melbourne, both with populations of around 5 million residents, have traditionally attracted Australia’s highest rates of population growth, which is primarily driven by international migration. Brisbane, Australia’s third largest city and the capital of the northeastern state of Queensland, has grown steadily due to internal migration that increased notably over the pandemic period, resulting in a very low rental vacancy rate of 1.5% (SQM Research, Citation2021).Footnote1 Housing stress has been chronic in all three cities but most acute in Sydney, where more than 90% of very-low-income earners spend more than 30% of their income on rent (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021).

Nationally, around a quarter of Australians live in the private rental sector; this has risen steadily over two decades in response to affordability pressures and barriers to first-home ownership (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022). The rental sector has been dominated by individual landlords with small portfolios, often consisting of single houses or apartments (Pawson & Martin, Citation2021). Professional real estate agents typically manage rental properties on behalf of landlords, administering residential tenancy leases in line with state regulations. Only around 3% of households live in social housing, and government investment in this sector has been falling since the mid-1990s. The lack of purpose-built rental accommodation has meant that rental leases typically run for a 6- to 12-month period, with tenants vulnerable to rental increases and sudden eviction without cause.

Housing Assistance and Urban Planning in Australia

Under Australia’s federal system of government, the commonwealth provides social welfare support in the form of unemployment benefit, the aged pension, and disability payments. A modest Commonwealth Rental Assistance is provided to 1.3 million very-low-income households, although it remains insufficient to relieve affordability pressures, with more than 44% of recipients continuing to spend more than 30% of their income in rent in 2022 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2023). The commonwealth and states jointly fund social housing and related housing assistance programs, including Aboriginal housing and crisis accommodation services.

The states retain responsibility for urban planning, and each jurisdiction has adopted different regulatory frameworks that bind local government zoning regimes. These differences play out in land use controls applying to traditional forms of low-cost rental and marginal accommodation such as boarding houses (offering single-room accommodations) and secondary dwellings (a detached or attached unit usually constructed to the rear of a primary residence). All three state jurisdictions in our study and their capital cities—New South Wales (Sydney), Victoria (Melbourne), and Queensland (Brisbane)—have sought to enable new boarding houses as a source of lower-cost accommodation for very-low-income earners and to help offset the loss of traditional single-room occupancy accommodation that is under redevelopment pressure.

The state of New South Wales has also sought to enable other diverse housing typologies produced by the market to expand the rental housing stock. Under its State Environmental Planning Policy–Affordable Rental Housing, introduced in 2009, secondary dwellings meeting code requirements for allotment size, boundary setbacks, and building design are permitted in most residential areas regardless of local controls to the contrary. In Brisbane the rules on secondary dwellings have been shifting but remained restrictive at the time this study was carried out. Secondary dwellings are tightly controlled in most of Victoria, subject to different local council rules as well as rental restrictions that limit occupants to those who have a relationship with residents of the primary dwelling.

Methods and Data

Our listings data were collected from four separate platforms that collectively encompass the real estate, share, and short-term rental housing markets in Australia. summarizes these platforms and the types of residential accommodation they offer.

Table 1 Australian online housing platforms and rental market segments.

The platform Realestate.com.au dominates advertisements for residential property in Australia, with listings placed by professional real estate agents. As shown in , the accommodation listed on this platform ranged from whole houses and apartments through to secondary dwellings, boarding houses, and room rentals targeting renters across the income continuum. The peer-to-peer platform Gumtree.com.au advertises a variety of goods and services, but our focus in this study was on the rental accommodation listings placed by owner-landlords. Much of this accommodation was self-contained and thus targeted low-income households seeking private space. Flatmates.com.au was designed solely for the share housing sector and targets those offering or seeking forms of share accommodation. Listings are often placed by existing share households or people seeking room in an established share home. We also included the short-term rental platform Airbnb.com in our analysis, which remains the largest platform for residential tourist accommodation in our three case study cities.

Differences across the range of listings and information contained on these platforms meant it was necessary to use different methods of data collection and analysis for each. Airbnb and Flatmates.com.au data were able to be scraped for automated aggregation, whereas the free-text descriptions and visual images on the Realestate.com.au and Gumtree.com.au platforms needed to be manually scraped, downloaded, and classified.

Classifying Informal Dwellings and Tenures

As a platform designed for share housing advertisements, listings on Flatmates.com.au were able to be web-scraped and sorted into set categories relating to location, asking rent, type of share arrangement (private or shared room), leasehold period, and household size. We coded full free-text descriptions of advertisements to identify key themes relating to the characteristics and preferences of people seeking and offering share accommodation, assisting us in validating and interpreting our quantitative data.

We commissioned the independent nonprofit InsideAirbnb.com to supply data on Airbnb listings for each city. InsideAirbnb.com data have been used in numerous studies of the short-term rental sector and are considered reliable in the absence of information supplied by the Airbnb platform itself (Ferreri & Sanyal, Citation2018). Available data categories include the location of listings; whether listings are for whole homes, rooms, or shared rooms; how often properties are available for booking (frequently available and booked properties indicate dwellings that are not used as permanent residences); and rental costs. Our intention in this study was to understand the extent of informal tourism occurring within residential housing, whether by owners or renters offering their own homes or landlords offering their property to tourists rather than residents (indicated by dwellings available for 90 or more nights per year).

Many different types of rental accommodation are advertised on the platform Gumtree.com.au. To avoid potential duplication with Realestate.com.au listings, we focused the Gumtree analysis only on advertisements by owner, whereby tenants rent directly from their landlord, who may even reside on the property. As noted, this is not a standard arrangement in Australia and indicates an agreement negotiated directly between landlord and tenant rather than formal leasing handled by a professional real estate agent operating according to state residential tenancy law. Such leases cover the duration of tenancy (with minimum periods of 6 months or longer), potential grounds for eviction, protocols for property inspection, and so on.

We developed a detailed protocol for identifying informal dwellings listed on Realestate.com.au. First, total rental listings on Realestate.com.au for each city were initially reviewed to determine a price threshold for screening advertisements likely to meet informality criteria, which previous research has shown tends toward lower rental costs (Zhang & Gurran, Citation2021). We found that in each city AU$325 per week (around the maximum amount affordable to a low-income earner) represented a meaningful boundary between formal rental units (typically one-bedroom or studio apartments) and informal accommodation arrangements (e.g., room rentals) or dwelling types (e.g., secondary units or boarding houses). This initial sorting approach allowed the research assistants to concentrate their detailed manual analysis on a manageable sample of accommodation listings.

A combination of listings text and accompanying photographs was then used to classify these lower-cost offerings advertised on Realestate.com.au: from a standard house or apartment (excluded from analysis), to a room or shared room, secondary dwellings meeting/not meeting regulatory standards, and a formal or informal boarding house. This subset of advertisements meeting informal criteria was then subject to more detailed analysis, followed up by field visits to view a sample of advertised vacancies in Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne. We were informed by our review of the relevant planning and building regulations applying to each jurisdiction in classifying accommodation according to these categories.

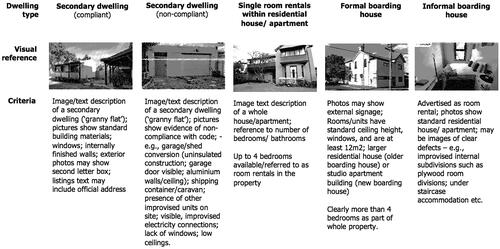

As shown in , several visual and text-based indicators were used to classify informal dwelling types on Realestate.com.au. Obvious building defects apparent in visual images, such as plywood room dividers, uninsulated constructions, improvised power sources, low ceiling heights, and so on, provided evidence of noncompliance with planning or building rules. Similarly, nonstandard forms of dwellings, such as caravans or shipping containers, were classified as noncompliant secondary dwellings.

Study Period

We extracted data from each platform for the period August 2021, selected to coincide with the nation’s 5-year population census. This allowed us to benchmark platform-harvested data with standard population-wide information on households and housing tenure. However, the period was somewhat atypical, with Australia’s international borders still closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Rental demand for central city locations was thus weaker than typical in previous years, largely due to the lack of international students and government work-from-home directives that allowed people to relocate to suburban or regional destinations (Buckle et al., Citation2020). Demand for short-term rental accommodation in these three largest cities was considered largely dormant during the period as well due to the lack of international tourists (Buckle et al., Citation2020). At the same time, Australia’s housing affordability pressures remained, with house prices rising to historic highs due to government grants for home purchases and residential construction and very low mortgage interest rates.

Statistical Analysis

Recognizing the limitations in using platform-generated information to understand housing markets (Boeing et al., Citation2021), we compared our data against available real estate industry indicators and Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census data. Note that although the ABS seeks to identify all of Australia’s households and dwellings, it relies on registered address data for quality assurance. Therefore, it may miss some informal dwellings that do not have a registered address, as is often the case when secondary units have been created without permission. To examine the extent to which our sample of informal listings contributed to rental supply, we referred to publicly available vacancy rate data published by SQM Research, an industry data provider. This analysis, discussed below and summarized in , showed first that share housing listings captured via our data represented a consistent and meaningful proportion of known group households (more than 3% in each city) and, second, that our sample extends the overall rental vacancy rate by a measurable degree (between 0.6% and 0.9%). We also tested the correlation between the spatial distribution of our informal housing data set and ABS-enumerated rental dwellings and group (share) households at the finer-grained scale (suburb level), finding consistent patterns (). This benchmarking and triangulation helped validate our data on informal rental supply, but we do not claim to capture all the other digital and real-life social networks that also offer access to informal rental accommodation across the three cities.

Table 2 Overview of informal housing listings on Realestate.com.au., Gumtree.com.au, Flatmates.com.au, and Airbnb.com, August 2021.

Table 3 Pearson correlation coefficients of informal housing listings versus rented dwellings and group households in three cities.

Findings: A Typology of Informal Rental Housing

Our data show that a variety of informal dwellings and tenures form a distinct sector of Australia’s housing system. Excluding properties listed on Airbnb (which depleted rather than added to the rental housing stock), a total of the 11,122 dwellings advertised via the selected three platforms in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane met the criteria for informal accommodation. These informal housing listings amounted to 57% of the total 19,410 collected listings on these three platforms. When considered against wider market data on the rental vacancy rate and median rents and population characteristics (the total number of rental households and group households) in each city, the scale and significance of informal rental listings relative to the wider housing market were apparent (). As noted, however, the period of analysis was somewhat anomalous due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw international border closures and domestic migration from Melbourne and Sydney to Brisbane and other parts of regional Australia. As a result, Sydney and Melbourne recorded much higher vacancy rates in the formal rental sector (3% and 4%, respectively) over the study period, whereas Brisbane recorded a tight vacancy rate of only 1.5% ().

The quantity and nature of informal rental listings were consistent across each city, although Melbourne recorded the highest number of informal listings (4,942). In Brisbane, the number of informal rental listings represented a higher proportion of the formal rental vacancy rate (44.6%), reflecting the tight rental conditions in that city during August 2021 and its smaller overall population size. The finding further suggests that Brisbane’s informal sector may have expanded in response to shortages in formal rental supply.

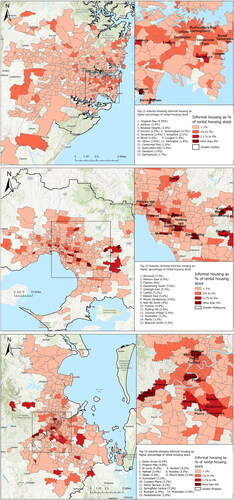

It is striking that the spatial distribution of informal listings appeared to follow similar patterns across all three cities. As shown in the suburb-level analysis of listings, these patterns concentrated around the main business districts and employment centers. This finding suggests consistency in this sector of the rental market, implying data reliability (). However, some differences in the geography of informal listings by platform appeared in this suburb-level analysis, with properties listed by owners on Gumtree.com.au tending toward middle- and outer-ring areas of lower housing density. By contrast, Airbnb listings tended to focus on inner-city, airport, and waterside localities, consistent with locations of high visitor appeal.

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of total informal housing listings as percentage of rental housing stock in three cities. Source: Derived from Realestate.com.au, Citation2021; Gumtree.com.au, Citation2021; Flatmates.com.au, Citation2021; ABS, Citation2022.

Composition of Informal Housing Supply

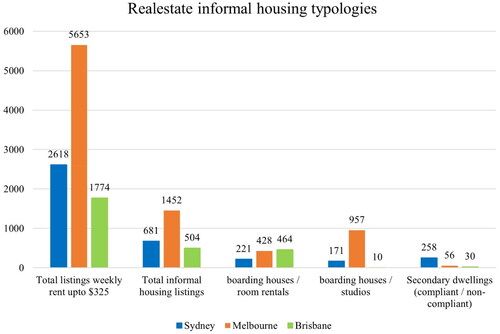

The composition of informal offerings differed in each city, perhaps reflecting different geographic and market conditions as well as planning and regulatory frameworks. Looking closely at advertisements on the platform Realestate.com.au, patterns emerged that were largely consistent with known data about dwelling typologies in each city. Room rentals—typically a semi-furnished bedroom within a detached suburban house—dominated the informal rental stock in Brisbane (464 listings). The number of room rentals advertised by real estate agents via this platform (rather than owner or renter households seeking a lodger or flatmate, as occurs via Flatmates.com.au), indicated a new single-room occupancy typology distinct from traditional boarding house accommodation. A similar number of room rentals was also recorded in Melbourne (n = 428), but these were outnumbered by self-contained boarding house studios (n = 957; ).

Figure 3. Composition of informal housing supply on real estate, August 2021. Source: Derived from Realestate.com.au, Citation2021; Gumtree.com.au, Citation2021; Flatmates.com.au, Citation2021.

The shift to agent-organized room rentals (rather than more organic, resident-organized share homes) was not necessarily enabled by platform technology; real estate agents have always offered rental housing in Australia. But real estate agents have not typically issued leases for these arrangements that were organized directly by share households or boarding house providers. The new practice of marketing properties by the room or bed rather than as a single unit may offer a higher overall yield for landlords than offering a whole dwelling to a single household and suggests a commercialization of traditional self-organized share accommodation.

There was more even distribution across the different informal housing categories in Sydney, with secondary dwellings amounting to more than a third of listings advertised on Realestate.com.au (), reflecting the long-established New South Wales planning policy for enabling construction of this housing typology as a strategy for low-cost rental supply. Notably, noncompliant secondary dwellings amounted to about 13% of the informal housing listings we captured within the rental threshold of up to $325 per week (94 listings). This suggests that despite a formal, codified pathway for constructing secondary dwellings that comply with planning rules, providers have continued to offer informal and unauthorized units in Sydney.

Cost of Platform-Enabled Informal Housing Supply

As noted above, not all informal housing is necessarily low cost or affordable to people with low incomes. Putting aside Airbnb listings that target tourists and other short-term visitors, less than half of the Gumtree advertisements we analyzed were advertised for rents of less than $325 per week (33%, 30%, and 43% for Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane, respectively; ). Most of the Melbourne and Brisbane share housing listings on Flatmates fell beneath the $325 benchmark. In Sydney, 82% of Flatmates listings met this criterion, highlighting high housing costs even in the share sector. By contrast, of the total listings advertised on Realestate.com under $325, fewer than half were for informal typologies such as boarding houses or secondary units ().

Intersections With the Formal Housing System

As outlined above, the literature has emphasized close interrelationships between informal and formal systems (Harris, Citation2018; Roy, Citation2005). These are reflected in our findings, which highlight complex market intersections between formal and informal rental sectors. First, there were strong spatial relationships between the geography of formal and informal rental markets. To test and measure this relationship between informal housing listings and rental housing stock as well as group households in the three cities, we performed Pearson correlation at a finer-grained scale, using the suburb level as the unit of analysis (). This analysis confirmed that spatial distribution mirrored the geography of enumerated rental households and group households, and scatterplots demonstrated positive linear relationships between informal housing listings and rental housing stock in all three cities.

In Sydney, informal housing listings showed a very high correlation (p < .001) with rental dwellings (.825) and group households (.881).Footnote2 A similar association was found for Melbourne (p < .001), which showed very high correlation between informal housing listings and rental housing stock (.679) as well as group households (.781). In Brisbane, the correlation value between informal housing listings and rental housing stock was slightly lower (.495) than the threshold .5 value, yet still indicated a positive linear relationship with p < .001.

The second key intersection with the formal housing system related to market feedbacks. As outlined above, informal listings identified in our study made a significant contribution to supply, amounting to between 20% and 45% of vacancy rates in Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane (). However, dwellings advertised on the informal short-term rental platform Airbnb had the opposite effect, amounting to 72% of rental vacancies in the case of Brisbane.

These relationships are likely dynamic. To the extent that unmet need for lower-cost rental housing may drive demand for informal alternatives, rising rents and low vacancy rates in the formal sector may increase the likelihood of people advertising for flatmates or offering a room in their home via platforms such as Airbnb. Similarly, some landlords may seek to exploit tight rental housing conditions by constructing a secondary dwelling and/or renting their property by the room, maximizing rental yields. This appeared to be occurring more in Brisbane, where we found many room rentals in new detached homes on the suburban fringe.

Intersections With Planning

Consistent with the wider literature outlined above, the informal rental practices we identified intersect with the planning system in complex ways. Whereas many practices violated planning rules, others have been legitimized by formal planning systems, and all raised particular risks for residents and implications for planners. We summarize these intersections in , identifying risks and potential planning responses in relation to our typology of informal rental accommodation.

Table 4 Informal rental accommodation and potential planning responses.

As shown in , informal tenures such as share homes and apartments, as well as room rental arrangements, represented significant risks associated with potential for social conflict between residents, insecure tenure, and overcrowding, as well as compromises in relation to privacy and interpersonal relationships. Some of these risks may be minimized through design solutions addressing issues such as the interface between private and shared spaces, storage options, and noise. Similar considerations arose in relation to secondary dwellings and boarding houses. Where secondary dwellings and boarding houses failed to comply with local planning rules, residents faced significant risks to health and safety in addition to the wider implications for neighboring properties and local infrastructure and services.

Notably, it is not clear from our data that reforms to promote new and code-compliant secondary dwellings and boarding houses would necessarily reduce illegal and noncompliant units. For instance, the very high number of secondary dwellings in Sydney relative to the other cities was almost matched by high numbers of informal units as well.

In these instances, planning responses may include education of property owners, pathways to formalize noncompliant units and buildings, and enforcement action where there are serious dangers to occupants or surrounding residents. However, in the absence of alternative housing options for low-income residents, it is not clear that a punitive response to enforce code requirements would always be the most appropriate course of action (Wegmann & Mawhorter, Citation2017).

In sum, the rise of informal housing practices across the private rental market might help alleviate entrenched housing pressures, even in the short term, for those with few other options. However, though informal sector rents were generally below those in the formal market, they were not necessarily affordable for lower-income earners and were associated with significant compromises on tenure security and/or domestic amenities and privacy. This suggests that planning policies designed to increase lower-cost rental supply by enabling informal and diverse housing typologies may need to be matched by rules ensuring that rents are indeed more affordable and that rental tenancy protections for vulnerable tenants are in place.

Further, our data set provided a limited window into the informal substrata of the housing market, demonstrating the potential to inform local planning efforts. Such data can provide useful and time-sensitive indicators of shifts in housing demand and the level of unmet housing need, identifying cohorts who may be at increased risk of homelessness.

Yet in responding to this unmet need, cities need strategies to address the underlying drivers of unmet housing needs as well as the emergence of illegal and risky rental accommodation. Strategies will need to be tailored to the local situation but may involve educating vulnerable renters about their tenancy rights, informing those offering residential accommodation about their regulatory obligations, preventing the conversion of rental units to short-term rental accommodation, and establishing pathways for legalized construction or conversion of secondary dwellings and other forms of low-cost rental supply.

Conclusions: Planning for New Housing Practices

Overall, our study has shown that beyond the conventional housing units offered for sale and rent within the parameters established by planning and property regulation, online platforms have enabled and exposed a vast substrata of informal housing practices ranging from forms of self-organized share households and informal rental leases to illegally constructed units, subdivided apartments, and room rentals on one hand, to residential tourist accommodations on the other. These complex typologies of informally provided rental housing practices serve an important role in Australia’s housing system but are barely recognized by policymakers or captured by official data sources. With inadequate provision of social housing or rental subsidy for those on lower incomes, dependence on such marginal, insecure, and inadequate housing is likely to increase.

Our study also reflected more microlevel failures to enact and enforce appropriate land use planning and construction rules for housing development. The challenge for planners is to determine which regulatory strategies best support affordability and enable flexible and appropriate responses to different housing circumstances without generating unacceptable risks for residents and neighborhoods. Similarly, our data have demonstrated the extent to which short-term rentals have penetrated Australia’s high-demand rental markets, reflecting a regulatory failure to preserve residential homes or protect the rights of local renters.

These findings have varying implications for platform users and wider urban systems. They raise dilemmas for planners and local officials seeking to enforce residential amenities and standards, including the basic health and safety provisions critical to protect vulnerable and low-income renters, in the absence of wider housing system reform.

Finally, our study contributes to the emerging body of literature on the increasing role of platforms in transforming housing practices and in enabling and exposing informal market sectors. It is likely that many of the informal rental dwellings and tenures we have identified have long operated within Australia’s housing system but have been variously hidden or ignored and tolerated. The advent of online digital platforms has enabled a wider market and exposed them to researchers and policymakers, highlighting irregular, substandard, and illegal rental dwellings and potentially exploitative rental arrangements. Recognizing the critical role now served by the informal rental sector in accommodating lower-income earners with few alternatives, a regulatory enforcement response may not always be the best course of action. Informed by data on demand and supply in the informal rental sector, policymakers and regulators may instead opt to progress broader strategies for reducing unmet housing need; for instance, by supporting affordable construction, expanding income support, and protecting tenants from unfair eviction.

Technical Appendix

Download PDF (177 KB)Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2024.2326554

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicole Gurran

NICOLE GURRAN ([email protected]) is a professor of urban & regional planning in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney, Australia.

Zahra Nasreen

ZAHRA NASREEN ([email protected]) is a postdoctoral research associate in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney, Australia.

Pranita Shrestha

PRANITA SHRESTHA ([email protected]) is a postdoctoral research associate in the School of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney, Australia.

Notes

1 A 3% rental vacancy rate indicates a balanced market in Australia.

2 A correlation value of more than 0.5 indicates high correlation between variables (Boslaugh, Citation2012).

References

- Anacker, K. B., & Niedt, C. (2023). Classifying regulatory approaches of jurisdictions for accessory dwelling units: The case of Long Island. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 43(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19856068

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). 2021 Australian census. ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Housing assistance in Australia. AIHW.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2023). Housing assistance in Australia. AIHW.

- Boeing, G., Besbris, M., Schachter, A., & Kuk, J. (2021). Housing search in the age of big data: Smarter cities or the same old blind spots? Housing Policy Debate, 31(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1684336

- Boeing, G., & Waddell, P. (2017). New insights into rental housing markets across the United States: Web scraping and analyzing Craigslist rental listings. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 37(4), 457–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16664789

- Boslaugh, S. (2012). Statistics in a nutshell (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Buckle, C., Gurran, N., Phibbs, P., Harris, P., Lea, T., & Shrivastava, R. (2020). Marginal housing during COVID-19 (Report No. 348). AHURI Final Report. https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri7325501

- Chiodelli, F., & Baglione, V. (2014). Living together privately: For a cautious reading of cohousing. Urban Research & Practice, 7(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2013.827905

- Chiodelli, F., Coppola, A., Belotti, E., Berruti, G., Marinaro, I. C., Curci, F., & Zanfi, F. (2021). The production of informal space: A critical atlas of housing informalities in Italy between public institutions and political strategies. Progress in Planning, 149, 100495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2020.100495

- Devlin, R. T. (2018). Asking ‘Third World questions’ of First World informality: Using Southern theory to parse needs from desires in an analysis of informal urbanism of the global North. Planning Theory, 17(4), 568–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095217737347

- Durst, N. J., & Wegmann, J. (2017). Informal housing in the United States. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 282–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12444

- Ferreri, M., & Sanyal, R. (2018). Platform economies and urban planning: Airbnb and regulated deregulation in London. Urban Studies, 55(15), 3353–3368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017751982

- Ferreri, M., & Sanyal, R. (2022). Digital informalisation: Rental housing, platforms, and the management of risk. Housing Studies, 37(6), 1035–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.2009779

- Fields, D., & Rogers, D. (2021). Towards a critical housing studies research agenda on platform real estate. Housing, Theory and Society, 38(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2019.1670724

- Flatmates.com.au. (2021). Website. REA Group.

- Gumtree.com.au. (2021). Website. Gumtree.

- Gurran, N., Pill, M., & Maalsen, S. (2021). Hidden homes? Uncovering Sydney’s informal housing market. Urban Studies, 58(8), 1712–1731. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020915822

- Gurran, N., & Sadowski, J. (2019). Regulatory combat? How the “sharing economy” is disrupting planning practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 20(2), 274–279.

- Harris, R. (2018). Modes of informal urban development: A global phenomenon. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412217737340

- Harten, J. G., Kim, A. M., & Brazier, J. C. (2021). Real and fake data in Shanghai’s informal rental housing market: Groundtruthing data scraped from the internet. Urban Studies, 58(9), 1831–1845. https://doi.org/10.1177/doi:10.1177/0042098020918196

- Maalsen, S., Shrestha, P., & Gurran, N. (2022). Informal housing practices in the global north: Digital technologies, methods, and ethics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2026889

- Mendez, P. (2017). Linkages between the formal and informal sectors in a Canadian housing market: Vancouver and its secondary suite rentals. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 61(4), 550–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12410

- Mendez, P., & Quastel, N. (2015). Subterranean commodification: Informal housing and the legalization of basement suites in Vancouver from 1928 to 2009. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1155–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12337

- Nasreen, Z., & Ruming, K. J. (2021). Informality, the marginalised and regulatory inadequacies: A case study of tenants’ experiences of shared room housing in Sydney, Australia. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(2), 220–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1803531

- Nasreen, Z., & Ruming, K. (2022). Struggles and opportunities at the platform interface: Tenants’ experiences of navigating shared room housing using digital platforms in Sydney. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 37(3), 1537–1554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09909-x

- Parkinson, S., James, A., & Liu, E. (2018). Navigating a changing private rental sector: Opportunities and challenges for low-income renters. AHURI.

- Pawson, H., & Martin, C. (2021). Rental property investment in disadvantaged areas: The means and motivations of Western Sydney’s new landlords. Housing Studies, 36(5), 621–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1709806

- Porter, L., Fields, D., Landau-Ward, A., Rogers, D., Sadowski, J., Maalsen, S., Kitchin, R., Dawkins, O., Young, G., & Bates, L. K. (2019). Planning, land and housing in the digital data revolution/the politics of digital transformations of housing/digital innovations, PropTech and housing—the view from Melbourne/digital housing and renters: Disrupting the Australian rental bond system and tenant advocacy/prospects for an intelligent planning system/what are the prospects for a politically intelligent planning system? Planning Theory & Practice, 20(4), 575–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1651997

- Rae, A. (2015). Online housing search and the geography of submarkets. Housing Studies, 30(3), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2014.974142

- Realestate.com.au. (2021). Website. REA Group.

- Rolnik, R. (2013). Late neoliberalism: The financialization of homeownership and housing rights. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(3), 1058–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12062

- Ronald, R., Schijf, P., & Donovan, K. (2023). The institutionalization of shared rental housing and commercial co-living. Housing Studies, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2023.2176830

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- Shrestha, P., Gurran, N., & Maalsen, S. (2021). Informal housing practices. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1893982

- SQM Research. (2021). Residential vacancy rates; Region brisbane CBD. https://sqmresearch.com.au/graph_vacancy.php?sfx=®ion=qld%3A%3ASouthern+Brisbane&t=1

- Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wachsmuth, D., & Weisler, A. (2018). Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(6), 1147–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18778038

- Wainwright, T. (2022). Rental proptech platforms: Changing landlord and tenant power relations in the UK private rental sector? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 55(2), 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221126522

- Wegmann, J., & Chapple, K. (2014). Hidden density in single-family neighborhoods: Backyard cottages as an equitable smart growth strategy. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 7(3), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2013.879453

- Wegmann, J., & Mawhorter, S. (2017). Measuring informal housing production in California cities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1288162

- Wetzstein, S. (2022). Toward affordable cities? Critically exploring the market-based housing supply policy proposition. Housing Policy Debate, 32(3), 506–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2021.1871932

- Zhang, Y., & Gurran, N. (2021). Understanding the share housing sector: A geography of group housing supply in metropolitan sydney. Urban Policy and Research, 39(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2020.1847067