Abstract

How does a housing crisis become a crisis? In answering this question, this paper turns to framing in public and political debate. The case is the Netherlands where in the decade following the Global Financial Crisis the debate on housing quickly developed. Drawing on a discursive analysis of parliamentary documents, newspaper items, and interviews, the paper reveals how a housing crisis frame became central in debate, through a sequence of incubation, development and escalation. These debates shown signs of politicization as they increasingly emphasize the structural causes and political roots of the current situation, while also framing housing as primarily a fundamental right rather than a market commodity. This politicization, however, is matched by depoliticizing tendencies as relatively much attention is directed to the housing issues of the middle classes and young adults. Findings help us understand how housing struggles are understood, and which policies are deemed acceptable and necessary.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

It is Sunday 12 September 2021 when around 15,000 people have gathered in front of a large stage in Amsterdam’s Westerpark. They are there for what national media coverage had already dubbed the largest housing protest in the Netherlands since the 1980s. Many people gathered in the park brought signs with texts like “housing is a human right” and “people over profit”. Leaders of local and national political parties are in attendance, supporting the cries for a different, more social housing politics in which housing is embraced as a crucial human right. A month later, in October 2021, almost 10,000 people attended a similar housing protest in Rotterdam, where the riot police eventually violently cracked down on some of the protesters in attendance. A string of smaller-scale protests would quickly follow in other cities across the country. A spark had been ignited.

The organizers of the protests very clearly and explicitly framed the current housing situation as a crisis situation. The first lines on their website (woonprotest.nl) read:

“There is a colossal housing crisis in our country. Housing is increasingly difficult to afford for more and more people and the crisis creates more victims every day. Hundred-thousands of people are on years-long waiting lists [for social-rental housing], house prices are skyrocketing and the number of homeless people has doubled in ten years.”

In this paper, I address the question how and why the housing crisis became a prominent fixture in Dutch political and public debate in the years following the global financial crisis. While actually worsening housing conditions for many certainly play a role in this dynamic, this paper zooms in on how the debate itself developed with different frames competing for primacy.

Conceptually, this paper seeks to advance understanding of how a housing crisis discursively comes into being. This is an important empirical and conceptual question because how an issue is framed, and by whom, influences which solutions are deemed necessary and realistic. This paper seeks to provide an answer by combining insights from the field of crisis management studies with those from the political economy of housing. Drawing on the former strand of crisis literature, the paper first traces how the Dutch housing debate evolved after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). It shows how this debate was mostly absent in the years directly after the economic crisis, in what may be called a period of incubation (see Boin et al., Citation2020). The debate subsequently developed and escalated into a more critical “housing crisis” debate with more attention to the structural and political roots of the housing crisis, with competing frames focusing on different causes and solutions. Building on political economy of housing literatures, I conceptualize this development as a politicization of the housing crisis. Nevertheless, in the framing of the housing crisis relatively much attention goes out to the housing struggles of middle-income residents and young adults, with the risk of glancing over the housing struggles of other, more disadvantaged groups which may lead to depoliticization.

Empirically, the present paper builds on, and contributes to, previous scholarly work on the framing of housing crises across countries (e.g. Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; Heslop & Ormerod, Citation2020; White & Nandedkar, Citation2021). These studies have typically highlighted how industry lobbyists, developers and governments have appropriated the term “housing crisis” to depoliticize it, undo it of its radical potential and instead push for a market-friendly agenda. The results from the present paper complicate these conclusions by revealing a dynamic debate marked by processes of both politicization and depoliticization. The Dutch case, with all its specificities, thus reveals interesting similarities as well as contrasts with other studies predominantly originating from Anglophone contexts.

2. Literature

2.1. The material housing crisis

The introduction above starts from the assumption that a housing crisis is indeed unfolding in many societies, including the Netherlands. It is important to further unpack the notion of a housing crisis, which has both material and discursive dimensions.

A series of patterns and trends indeed point to increasing housing-based inequalities and hardships across countries. No clear definition exists of what actually constitutes a housing crisis, but recent scholarship suggests at least some commonly used empirical underpinnings. Wetzstein (Citation2017, p. 3159) for example speaks of a global urban housing affordability crisis, which for him is “the accelerating trend of housing-related household expenses rising faster than salary and wage increases in many urban centers around the world.” Writing about London’s housing crisis, Watt and Minton (Citation2016, p. 205) implicitly give a somewhat broader definition. They argue that the housing crisis comes in “varying degrees of severity ranging from the mild (over-indebted ‘mortgage slaves’), through the moderate (young professionals and students experiencing multiple private sector rent hikes and evictions), to the severe (those living in damp, overcrowded flats or in temporary accommodation) and ending at life-threatening (the street homeless).” In a similar vein, Heslop and Ormerod (Citation2020, p. 145) state that the housing crisis is difficult to define as it “does not only involve those in housing precarity, such as people experiencing homelessness, overcrowding or insecure tenancies, but also middle-class millennials struggling to get on the housing ladder.” From these loose definitions and operationalizations, it becomes clear that the concept of a housing crisis implies a certain broadness, hurting different populations in different ways.

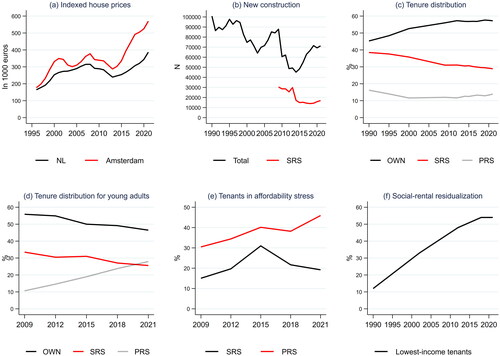

Various key indicators (summarized in ) underscore the variegated character of what may be considered the Dutch housing crisis. While being far from exhaustive, key aspects include the rapid increase in house prices, especially in cities such as Amsterdam () as well as some of the lowest rates of new constructions since WWII being recorded since 2010, with especially the construction of affordable social-housing in sharp decline (1b). Overall trends show stagnating homeownership rates and a gradual but continuous decline in affordable social-rental housing (1c). Among young adults (aged 25-34) tenure shifts are more pronounced with a notable decrease in homeownership as well as social rent, and an increasing dependence on private renting (1d). This latter trend has exposed populations to increasing precarity, as private tenants often depend on short-term leases while also finding themselves increasingly in housing affordability stress (1e). The Dutch social-rental sector still shields a sizeable share of the population from these adverse trends, but is subject to ongoing residualization (Boelhouwer & Priemus, Citation2014; Hoekstra, Citation2017; Van Gent & Hochstenbach, Citation2020). This is marked, among other things, by a decreasing size of the tenure (1c) following a slump in new constructions (1b) along with increasing social-housing sales post-GFC. Furthermore, government policies have increasingly restricted access to the social-rental sector to the lowest-income populations (1f) as the tenure is being remade from a broad service to a last resort tenure. As in other countries, the lack of affordable housing has contributed to a sharp increase in homelessness (Boesveldt & Loomans, Citation2023). While Statistics Netherlands registered 32,000 homeless working-age people in 2020 (compared to 18,000 in 2009), expert organizations employing a broader definition argue the actual number is much higher. Umbrella organization Valente for example speaks of 54,000 “clients” who experienced some form of homelessness in 2011, with this figure increasing to 100,000 in 2019.

Figure 1. Key indicators of the Dutch housing crisis: (a) house-price increases, (b) a slump in new constructions, (c) tenure shifts, (d) tenure shifts among young adults, (e) increasing housing affordability stress, and (f) social-housing residualization. Notes: (1) both axes differ per graph; (2) OWN = owner-occupation, SRS = social-rental sector, PRS = private-rental sector; (3) housing affordability stress is defined as spending more than 30% of gross income on basic rent (no utilities); (4) social-housing residualization is defined as the share of tenants belonging to the poorest 20% households. Sources: (a) own adaptation of CBS (Citation2023a); (b) own adaptation of CBS (Citation2023b) and Aedes data; (c) own adaptation of Musterd (Citation2014) and CBS (Citation2023c); (d) and (e) own calculations using the WoON survey; (f) own adaptation of SCP (Citation2017) and WoON survey calculations.

These general trends are not unique to the Netherlands but have similarly been identified in other European countries. Conceptually, they are part of a polarization of housing marked by a retreat in owner-occupation among some (McKee, Citation2012; Christophers, Citation2018; Ryan-Collins, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2022) and a re-concentration of property and housing wealth among others (Arundel, Citation2017; Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2018; Kadi et al., Citation2020; Adkins et al., Citation2021; Jacobs et al., Citation2022). They are part of processes of housing financialization (Aalbers, Citation2016) in which housing as an asset class is integrated in capital flows operating at various spatial scales, further accommodated by political agendas promoting housing liberalization, private ownership and accumulation as part of asset-based welfare strategies (Ronald, Citation2008; Crouch, Citation2009; Ronald et al., Citation2017) while also systemically eroding tenant protections and the provision of de-commodified housing alternatives more broadly (Byrne & Norris, Citation2022; Waldron, Citation2023; Howard et al., Citation2024).

2.2. The socially constructed housing crisis

The previous section has given a number of patterns and trends that can be considered emblematic of an unfolding housing crisis. However, crises are not natural or given phenomena, but are socially constructed. That is, a crisis only becomes a crisis when it is labelled and understood as such. Rosenthal et al. (Citation2001) define a crisis as a perceived threat to core values in society or life-sustaining systems that therefore requires urgent attention.

An increasing inability to acquire housing which subsequently frustrates progression along the life course may fit this definition of life-sustaining systems being undermined, while promises of independent housing and specifically private ownership may be considered of as core values in many (higher-income) societies. Defining a crisis typically allows for contesting interpretations of underlying causes, who is to blame, likely effects and necessary solutions. Indeed, the very act of diagnosing a (housing) crisis has an agenda-setting purpose (Boin et al. Citation2009, p.82), shaping which “remedies” are imaginable (Entman Citation1993).

The labelling of a housing crisis is thus an act of framing. Frames, Van Hulst and Yanow argue (2016, p.98) “are implicit theories of a situation: They model prior thought and ensuing action, rendering that action sensible in terms of pre-existing thinking”. They help making sense of and organizing the world (Goffman, Citation1974). Moving beyond static frames, Van Hulst and Yanow (Citation2016) propose a shift towards more dynamic and politically aware understandings of framing as interactive processes, organizing knowledge and values through sense-making (i.e. understanding what is going on), naming (i.e. categorizing and labelling) and storytelling (i.e. bringing together and connecting different features of the situation at hand). The intent of such framing, ultimately, is “to mobilize potential adherents and constituents, to garner bystander support, and to demobilize antagonists” (Benford & Snow, Citation2000, p.614).

Crises are typically conceived of as major, unforeseen shock events that subsequently trigger an immediate crisis response but have a longer-lasting impact on societal and political debates (e.g. Van Dooremalen & Uitermark, Citation2021). Think for instance of natural disasters or terrorist attacks. In contrast, a housing crisis is more akin towards what has been termed a creeping crisis, which also threatens societal values and systems but “evolves over time and space, is foreshadowed by precursor events, subject to varying degrees of political and/or societal attention, and impartially or insufficiently addressed by authorities” (Boin et al., Citation2020, p.122; also Drennan et al., Citation2014). A creeping crisis will, according to Boin and colleagues, typically incubate, develop and escalate – but only in this latter stage will it be recognized, or labelled, as a crisis. Escalation often involves a major focusing event which places the crisis situation which up to that point had been quietly building up in the spotlight (Boin et al., Citation2020).

Invoking a crisis triggers a response, as the crisis situation opens a window of opportunity for a change in policies or political constellations (Kingdon, Citation1993). Boin and colleagues (Citation2009, p.84) distinguish between frames denying, acknowledging and exploiting the crisis. Those representing the status quo may, at least initially, deny the crisis situation entirely with the aim of maintaining business-as-usual. In case this becomes untenable, these actors may instead acknowledge the crisis threat but seek to defend the system. They may propose incremental policy tweaks while exogenizing responsibility (i.e. the crisis is external to the current system, absolving it from blame). Conversely, critics may seek to exploit the crisis. They may invoke the frame that it is inherent, or endogenous, to the status-quo politics and that systemic change is a prerequisite to address the crisis. These different strategies involve different frames, each interpreting and constructing the crisis in different ways, with political officials, media, lobbyists and other key stakeholders playing a central role in determining which frames get selected and reproduced, i.e. the framing process (Heslop & Ormerod, Citation2020; also Jessop, Citation2013).

Various previous studies have focused on the framing of a housing crisis. Writing about England, Heslop and Ormerod (Citation2020) show how government, media and think tanks push a narrative in which the housing crisis is largely reduced to a lack of supply caused by overregulation (also Foye, Citation2022). Similarly, White and Nandedkar (Citation2021, p.205) note that political discourse in New Zealand favors a simplistic framing, identifying “poor land supply and an inefficient planning system” as root causes. This market-oriented frame may come with a degree of positivity (Brill & Durrant, Citation2021): while it acknowledges the existence of a housing crisis, it also emphasizes solutions already exist. These are typically fixes and tweaks, with developers keen to implement them if not for an overregulated planning system. These frames have been criticized for forwarding solutions that call for market-friendly solutions of deregulation and commodification (Wetzstein, Citation2017), foreclosing the scope for more fundamental politicization (Nethercote, Citation2022) or even stigmatizing de-commodified alternatives, such as social housing, as part of the problem rather than the solution (Slater, Citation2018).

Yet, vested interests certainly do not have a monopoly on interpreting, labelling and mobilizing the housing crisis to suit their own agenda. Actors challenging the status quo may do so as well (Card, Citation2022; Martínez & Gil, Citation2022). A key potential for social movements is that frames can put the spotlight on the unacceptable housing realities of those most in need (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016) and instead forward imaginaries of housing as an important site of care and solidarity, rather than exclusion and exploitation (Fields et al., Citation2023). In those cases, critics exploit the crisis by pointing to the systemic injustices that are considered endogenous to current politics, thus calling for fundamental political-ideological alternatives.

2.3. Class dynamics in framing the housing crisis

The above helps us understand how frames shape how we conceive of certain problems, their causes and the solutions deemed necessary. What it does not explain, however, is why the housing crisis emerged as a topic in public and political debate in the first place. For Madden and Marcuse (Citation2016, p. 10), the housing crisis is far from a new phenomenon but rather a permanent feature of capitalist society: “for the oppressed, housing is always in crisis.” They therefore ask the question whose crisis we are talking about here?

In answering this question it is first important to recognize that housing positions are not only crucially shaped by class position and economic inequalities, but are in turn also key in shaping and reproducing these, and increasingly so. Building on classic literatures discussing the relevance of “housing classes” (e.g. Rex & Moore, Citation1967; Dunleavy, Citation1979; Saunders, Citation1984), recent studies argue housing is increasingly central in facilitating accumulation and defining class position. Following Piketty (Citation2014), these studies identify that while incomes from labour for many stagnated, generating wealth through asset ownership has become increasingly important with – colloquially stated – many homes earning more than jobs (Ryan-Collins & Murray, Citation2021). The ownership of property, or even multiple properties, then becomes increasingly important in shaping economic position and drawing class lines (Forrest & Hirayama, Citation2018; Kadi et al., Citation2020; Adkins et al., Citation2021; Hochstenbach, Citation2022a).

These housing classes do not only have disparate economic positions but also disparate class interests (Harvey, Citation1974). As many countries are dominated by an electoral majority of homeowners, who typically find themselves in higher social positions than renters, this makes them a powerful class interest group able to exercise electoral power to prioritize pro-homeownership and anti-welfare policies, such as redistribution through de-commodified housing while supporting high house prices to facilitate wealth accumulation (Ansell, Citation2014; André & Dewilde, Citation2016; Ansell & Cansunar, Citation2021). The result is a reproduction of a forceful ideology of homeownership (Ronald, Citation2008), promising not only financial security through owner-occupancy but also status, control, autonomy and other merits. The electoral majority of homeowners, then, makes it politically unfeasible to pursue policies that reduce inequalities between property-owning insiders and outsiders struggling with rental unaffordability and precarity.

Research from the Netherlands (Schakel, Citation2021) and elsewhere (Giger et al., Citation2012; Gilens & Page, Citation2014) has shown politics to be much more responsive to the concerns and desires of a higher-income and highly-educated electorate – which are highly overrepresented among homeowning majorities. Conversely, government policies appear virtually unresponsive to the concerns of lower-income populations. Their concerns are often only taken up when they line up with those of more affluent groups. Schakel (Citation2021, p. 41) proposes three key causal mechanisms that may explain this unequal responsiveness: (1) political participation tends to be weaker among lower-income groups, (2) politicians tend to be disproportionally selected from more affluent backgrounds leaving low-income groups underrepresented, and (3) the interests of high-income groups may be more aligned with those of influential interest groups, lobby organizations and corporations. Already in the 1970s, it was furthermore noted that politics is more responsive to protest groups when these are more resourced. Protestors with more economic, social or cultural capital are more likely to get their demands met (Schumaker, Citation1975; Giugni, Citation1998). Policymakers, meanwhile, also tend to follow a problem-solving approach, often depoliticizing political debates to technical measures they deem effective, executable and politically feasible (Preece, Citation2009).

Recent studies on the US and European countries find similar class biases in media coverage, although these patterns are weaker and more variegated in European countries (Jacobs et al., Citation2021; Matthews et al., Citation2021). These studies find that economic news coverage is strongly skewed towards the interests of rich households. Here, the vested interests of media owners, the middle-class habitus of many journalists, the ideological preferences of their readership and the focus on overall economic growth are offered as causal explanations (Jacobs et al., Citation2021).

These classed dynamics in politics and media may result in disproportionate attention to the housing fortunes of the middle classes and their inability to buy a home, and center on questions how to reinstate the “ideal” of homeownership (Norris & Lawson, Citation2023) while disregarding the structurally different housing struggles of those lower on the economic ladder. These dynamics of unequal responsiveness, I hypothesize, will structure if, when and how housing problems are problematized and, indeed, framed as a “housing crisis”.

3. Data and methods

To study how the Dutch housing debate evolved and the frame of a housing crisis became established, this paper combines various data. First, it draws on a structured analysis of all parliamentary documents mentioning the term “housing crisis” (wooncrisis or woningcrisis) for the parliamentary years 2000–2001 to 2021–2022.Footnote1 These documents include transcripts of meetings and debates in Dutch parliament and senate, official questions asked by members of parliament, and answers provided by ministers. All 305 documents mentioning the housing crisis were read and analyzed for the causes, effects, solutions and key actors they mentioned, as well as the political partisanship of involved politicians. Direct quotes from these documents are referenced as either Eerste Kamer (i.e. the Senate) or Tweede Kamer (i.e. the House of Representatives, or parliament).

Second, additional analyses were conducted of parliamentary documents mentioning related terms such as “housing shortage” (both woningtekort and woningnood) and combined queries which can be found in Appendix A. Apart from quantitatively tracing the use of these terms, I read and analyzed selected documents for their contents. These additional analyses give important insight into how political framing evolves over time and differs between parties.

Third, I analyzed news coverage of the housing crisis. Articles published in selected national newspapers mentioning the term housing crisis (wooncrisis) and related terms (see Appendix B) were accessed through the Nexis-database.Footnote2 The five largest national newspapers were included (Telegraaf, AD, Volkskrant, NRC and Trouw) as well as Het Parool, a national newspaper with a particular focus on Amsterdam that dedicates relatively much attention to housing issues. These newspapers hold various positions, from populist right-wing (Telegraaf) to progressive liberal (NRC) and social democratic (Volkskrant). A total of 675 newspaper items published between 2010 and 2022 mentioning the specific term housing crisis were found (668 of which were published between 2019 and 2022).

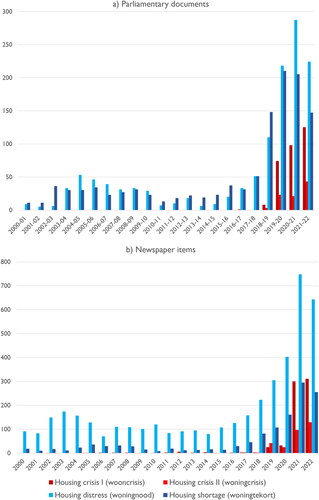

below gives a condensed overview of the annual use of the key queries housing crisis (wooncrisis/woningcrisis), housing shortage (woningtekort) and housing distress (woningnood) in both parliamentary notes and Dutch newspapers. These quantitative assessments have been used to structure subsequent analyses.

Figure 2. Number of parliamentary notes (panel a) and newspaper items (panel b) mentioning the terms housing crisis, housing shortage or housing distress per (parliamentary) year. Also see Appendices A and B for additional queries.

I subsequently manually selected items for close content analysis. In this process, I first discarded those items in which my own name was mentioned (see below for more on positionality) as well as items with less than 300 words (typically short factual updates, the threshold was decided to include most columns and op-eds). This left me with 605 items which I sorted by relevance (as determined by the Nexis-database). I then went through each item from top to bottom and discarded items that did not explicitly focus on housing but merely mentioned a housing crisis (e.g. in a list of “crises”, as a broad context, or occurring in other countries) until I had 100 items that met my criteria. The sampling is thus not random but based on my criteria and the computer-generated relevance hierarchy. I systematically analyzed these items, coding whether they focus on a specific tenure, specific populations, clearly locate a cause of the housing crisis and assess a solution.

Fourth, to gain a further understanding of the dynamics of these debates in public media, I interviewed the housing correspondents of three national newspapers. These journalists were sampled (a) because they were employed at one of the five major newspapers, and (b) because they had housing in their portfolio at the time of writing and/or during a substantial period under analysis. The semi-structured interviews focused on how they had seen public debate evolve, but also about how and why they choose to focus on certain topics (e.g. focusing on homeownership or renting, focusing on specific populations), as well as their choice for certain terms or concepts (such as “housing crisis” itself), and the response they got from their readership. Interviews were conducted online and recorded with informed consent and are anonymized.

In analyzing these data, I take cues from the crisis literature discussed in the literature section to interpret how housing crisis frames have evolved over time, and how this evolution triggers different strategies from different actors (Boin et al., Citation2009, Citation2020). Frames are crucial in shaping how individuals make sense of, organize and label the world (Goffman, Citation1974). They are imbued with meanings closely tied to ideology, preferences and interests, and linked to power and broader social processes (Fairclough, Citation1992). This requires paying attention to the political-ideological context in which frames are deployed as well as the political-ideological positions of those deploying them. By focusing on both parliamentary notes and newspaper items, this paper analyzes dynamic processes of framing, rather than static discourses as recorded in official policy documents (see Hastings, Citation2000).

A word on positionality is in order here. For the last couple of years, I have been active in public housing debates. I did so by writing essays for popular media, including a bi-weekly column for a news-website (2019–2021) and a popular-scientific book (Hochstenbach, Citation2022b). I also regularly commented on housing issues in various media and have given many public presentations. I have thus actively participated in the very debates I analyze in this paper. To account for this, I have made sure not to directly analyze, or draw on, news items I wrote, was cited in or contributed to in any other way. My involvement gave me access to key stakeholders shaping political and public debate. Indirectly, I build on various insights from dozens of informal and unstructured conversations with housing activists, members of parliament, local politicians and other relevant stakeholders. While these are not part of the formal analyses for this paper, they did help me understand the intricacies of Dutch housing debate.

The paper primarily focuses on the period following the GFC up until the end of 2022. This marks a period of constantly increasing house prices although by mid-2022 the war in Ukraine, soaring energy costs, spiking inflation and rising interest rates have ushered in a new period of uncertainty. The quantitative scan of key words described above serves as the basis for a rough periodization in which the narrative of a housing crisis incubated, developed and escalated. These do not represent discrete time periods but rather function as an analytical heuristic to understand how crisis narratives gradually unfolded. The focus is furthermore primarily at the national level, as more localized discourses and narratives may exhibit different patterns.

4. Results

4.1. Prelude: the housing-market crash (2008–2014)

During the 1990s and 2000s, access to mortgage credit was rapidly expanded with the Netherlands building up one of the highest levels of per capita mortgage debts in the world. New and ever more risky mortgage products were introduced such as interest-only mortgages, contributing to inflating house prices to unprecedented levels and also setting the scene for subsequent price drops (). During this period, public and political debates focused on a crisis on the housing market and mortgage market, as is evident from a spike in parliamentary documents and newspaper items mentioning such queries (see Appendices A and B, respectively). However, these debates were qualitatively different from the crisis frames that would emerge and escalate during the post-GFC period. Most importantly, this period was mostly about a cooling housing market – with declining prices leaving homeowners indebted – rather than an overheating one. This period of a housing-market downturn perhaps came to a symbolic closing in June 2014 when then housing minister Stef Blok (of the right-wing VVD party) spoke at the large annual Provada real-estate fair in Amsterdam. House prices slowly started to increase again and optimism was in the air. In a recorded interview, Blok sums up (in English) why now was the right time to invest in Dutch housing:

“What I heard here today was that there is very clearly a positive sentiment, because people see that we made the investment environment better by deregulating the rental sector, we created possibility to increase rents more, we bring back the social housing sector to their core business – social housing – thereby creating a level playing field for the commercial rental sector. We see that there is a lot of interest from Dutch households to find rental housing, we see that the population is still growing especially in the west of the country so I am convinced that there are good opportunities here in the Netherlands.”Footnote3

4.2. Incubation of the housing crisis debate (2014–2017)

From 2014 onwards, as house prices were steadily rising, decreasing numbers of owner-occupying households found themselves in net mortgage debt, leading to waning political and public attention to housing issues overall. This is quantitatively evident as the number of parliamentary documents or newspaper items (see Appendices A and B) discussing a housing-market or mortgage crisis showed a sharp drop after 2013. Simultaneously, these paid scant attention to other housing issues such as housing shortages (woningtekort) or housing distress (woningnood), while the notion of a housing crisis (wooncrisis/woningcrisis) was still completely absent.

This was thus a period of relative silence. In fact, through 2017 housing minister Blok pushed the frame that his market-oriented reforms had largely fixed the housing market which was now “running like a charm.” He believed market forces would be able to tackle future housing challenges and when, after national elections, the second center-right and market-liberal Rutte-cabinet made way for the third, the position of housing minister was completely scrapped. In a newspaper interview, Blok cheerfully stated: “I am the first VVD-member that has made a whole ministry disappear” (Cats, Citation2017).

Despite a dearth in political and media attention, the 2014–2017 period may be considered one of incubation for the housing crisis (cf. Boin et al., Citation2020). National house prices were steadily increasing, reaching levels last seen right before the outbreak of the GFC, housing production continued to lag behind demand, the number of renters struggling to pay their rent was increasing, as was also the case for the number of people experiencing homelessness. Preceding national debates, at the urban level, especially in Amsterdam, gentrification became increasingly politicized as it started to undermine the housing options for the middle classes (Boterman & Van Gent, Citation2023). A 2017 newspaper interview with urban scholar Richard Florida about his book The New Urban Crisis illustrates this well (Couzy, Citation2017; also see Florida, Citation2017). The interview draws parallels between Florida’s analysis of American cities and the Amsterdam situation, ultimately proposing solutions to specifically bring back the middle classes to the city. Gentrification thus evolved from a process that was deemed (in media and among policymakers) beneficial to the middle classes into one that posed a threat to them (see Tolfo & Doucet, Citation2021).

4.3. A developing national housing shortage (2017–2019)

As housing issues continued to deepen, the image that the Dutch housing market had recovered and was indeed “running like a charm” started to crack. Housing became a more prominent fixture in political and media debates over the 2017–2019 period, although it is important to recall here that the periodization presented here does not suggest discrete time periods but is an analytical heuristic to somewhat simplify a gradually evolving debate in which periods – and housing crisis narratives – bleed into one another.

Debate at this time, while developing, was very much a narrow and bracketed one. Focus was mostly on a lack of supply, not in the least because housing production had remained low during and post-GFC. This particular focus is quantitatively evident from a clear increase in the use of terms like woningtekort (housing shortage) and woningnood (housing distress) in parliamentary notes as well as newspaper items (see ). The latter term essentially also focuses on shortages, harking back to the years after the Second World War when the term was commonly used to describe urgent shortages.

Exemplary is a political exchange that followed in July 2017 after the Dutch realtor association published a press release warning about an increasingly dire housing shortage. This led Alexander Kops, a member of parliament for the radical-right PVV party, to ask the new Minister of the Interior Kajsa Ollongren (at that time responsible for housing):

“How many people or households are currently unable to buy a house because they are not available? How many people or households are currently unable to buy a house because these are too expensive or are unable to get the mortgage financed?” (Tweede Kamer, Citation2017).

The narrow focus suggests basic agreement among incumbent political parties, those in opposition as well as key stakeholders and lobby organizations. Acknowledging the problem at hand, incumbent political parties took to exogenizing blame for housing shortages, for example by pointing to policies by previous governments and lingering effects of the GFC. Mid-2018 minister Ollongren published a national housing agenda which started off as follows:

“Since the end of the crisis the difference between the demand for and supply of housing has massively increased. This is partly due to a combination of the rapidly improving economy, earlier measures on the housing market and catch-up demand from people who have waited out the crisis” (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Citation2018a, p.1).

Media discussions around these plans mostly revolved around questions how realistic these plans were, calling her plans to boost production “vague” (Van den Dool, Citation2018, p.2) or “an empty formality” (Bartels, Citation2018, p.25). While critics thus tried to responsibilize incumbent politics for deepening housing issues, they did so within the narrow frame of supply and demand.

The limited scope of these debates, focusing on shortages in supply and privileging homeownership, is largely in line with the market-oriented framing found in other studies (White & Nandedkar, Citation2021; Heslop & Ormerod, Citation2020; Wetzstein, Citation2017) in which the housing question is effected reduced to a technical question requiring a technical fix (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016).

4.4. An escalating national housing crisis (2019–2022)

Beginning in 2019 things started to change with a clear increase in the framing of a national housing crisis, i.e. making sense of housing problems as a crisis, naming it as such, and constructing a “story” around the roots of the situation (see Van Hulst & Yanow, Citation2016). Early that year, the term was first mentioned in parliament after which it rapidly gained traction (). The explicit labelling of a crisis situation contributed to politicization of housing debates in various ways: (1) it provoked broader debate about the structural causes and political roots of the housing crisis, giving rise to competing frames, (2) it illuminated the exclusions and inequalities engendered by the housing market, and (3) it popularized the notion of housing as a human right.

First, the notion of a housing crisis introduced a more complex and politicized understanding of contemporary housing problems. This gave rise to more explicitly competing frames over the various causes and solutions to the housing crisis. Initially, in parliament, this point was most vocally forwarded by socialist (SP) member of parliament Sandra Beckerman:

“I hope that everyone realizes that we are in the midst of a housing crisis, that the problems are complex and that political choices lie at its roots” (Tweede Kamer, Citation2019a).

“This housing crisis isn’t a natural disaster. This housing crisis is the result of failing politics. This housing crisis is the result of the wrong political choices” (Beckerman in Tweede Kamer, Citation2019b).

“Government is doing way too little to address this housing crisis. […] Minister Ollongren only talks but does far too little (Nijboer in Tweede Kamer, Citation2019b).

Also (radical) right-wing parties used crisis framing, but typically blaming climate and migration policies for, respectively, restricting supply due to overregulation while increasing demand due to excess migration. Here we see the construction of a competing frame that also makes use of a “crisis” situation, but does so by linking housing to other political domains.

By this time, incumbent politics was acknowledging the housing crisis but typically clung onto the logics of supply and demand. This position is best embodied by Daniel Koerhuis, member of parliament for the market-liberal VVD party (2017–2023), who kept repeating in traditional media, on social media and in parliament that the only solution is to “build, build, build” (e.g. see Muller & Timmer, Citation2021). In public media, this position was most often communicated by right-wing newspaper Telegraaf, often drawing on reports from influential think tanks and stakeholders like the Economic Institute for Construction or the Realtors’ Association (e.g. see De Jong, Citation2022 and Telegraaf, Citation2021, respectively).

Second, the housing crisis frame highlighted the stark and increasing housing inequalities between populations. The housing protests of late 2021 (mentioned in the introduction of this paper) play an interesting role here. On the one hand, they emphasize how the housing crisis is broadly experienced and impacts a large cross-section of the population. On the other hand, in all their communications, they prioritized the worst victims such as the increasing number of people made homeless, those barely able to pay the rent and those experiencing constant housing insecurity. This was a conscious decision, as Melissa Koutouzis – one of the lead organizers – explains:

“The housing crisis must be given much more faces. Not just the middle classes but particularly all other groups that are struggling much more need our attention” (quoted in Hochstenbach, Citation2022b, p.299).

“The moment you have a housing protest, afterwards as a journalist it is very nice that you can use these images of people being angry, holding signs with good slogans like “this isn’t a game of Monopoly”, that’s one I remember. I deliberately chose those for my articles because up to that point I simply used [stock images of] a house under construction or something […] That was really a turning point, the housing crisis was given a face” (interviewed housing journalist #1).

“What is clear, is that the housing crisis is bringing out a new division in society. I also heard this from many people who attended the protest. We see ‘insiders’, people who already have a home, and ‘outsiders’, people who are stuck and for whom it is increasingly complicated to get a decent and affordable roof over their heads at all” (Tweede Kamer, Citation2021a).

Third, and related to the human dimension, a key ingredient of the housing crisis framing focuses on housing being an essential human right – often pitched in direct opposition to housing as a market good (also see Pattillo, Citation2013). The housing protests played into this presumed dichotomy with slogans such as “housing for people, not for profit”, “people over market” and “housing is a right.”

Reference here is often made to the Dutch constitution, with article 22.2 stating that “it shall be the concern of the authorities to provide sufficient living accommodation” (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Citation2018b, p. 8). Nevertheless, it must be emphasized here that legal scholarship typically concludes that possibilities to enforce the right to housing via juridical means is limited (Vols, Citation2022). Instead, they conclude that housing as a right can be fruitful in politicizing the housing crisis. In other words, housing as a right is not primarily a legal claim but a political one (also Marcuse, Citation2009; Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016).

Indeed, already beginning before the 2021 housing protests, but subsequently accelerating, political parties would invoke the right to housing as a competing frame to put blame on incumbent politics and their market-oriented housing agenda, and their failure to uphold their constitutional obligations. Ironically, even incumbent political parties and politicians adopted this framing: when in January 2022 the fourth Rutte cabinet came into office and Hugo de Jonge – of the incumbent Christian Democrats (CDA) coalition partner – was installed as the new minister for housing, he adapted the housing-as-a-right frame to support stronger government intervention and suggest a symbolic break with previous governments, again an example of exogenizing blame to predecessors. In an interview with national newspaper Trouw he stated:

“For too long, we believed that the market would automatically ensure a balance between supply and demand. Housing is a fundamental right. We [national government] must regain control to fulfill that constitutional mandate” (cited in Obbink, Citation2022).

4.5. A middle-class housing crisis debate

Many media covering the housing protests, as suggested above an important focusing event, focused on the overrepresentation of young people – especially young, with and university-educated urbanites – in attendance, as well as on their specific housing problems such as their inability to buy a home or leave the parental home. The day after the Amsterdam housing protest, national newspaper NRC reported on the protests on its front page (Lievisse Adriaanse, Citation2021) with the article lead reading:

“The housing crisis affects everyone, but the housing protest in Amsterdam mainly attracted young people on Sunday. Especially they notice that good housing is almost unattainable.”

Moreover, rather than acknowledging that the experiences of young adults are highly divergent along the lines of class, they are typically treated as a singular group with a common experience. This was illustrated most extremely by an item in newspaper Het Parool just a few days before the Amsterdam protest, which claimed that even young adults who receive 100,000 euros in tax-free financial support from their parents were losing out on the overheated Amsterdam housing market (Smithuijsen, Citation2021, but see Van Gent et al., Citation2023 for an analysis of such transfers to support house purchases in Amsterdam).

This point has broader currency: a close analysis of the selected newspaper items reveals most attention is directed towards the housing woes of middle-income residents as well as young adults. These two groups are often mentioned in one breath, with the lines between the two blurring:

“Young adults and people with a middle income can’t find a house or have to put themselves into huge mortgage debts in order to buy something” (Telegraaf, Citation2021).

“We are not talking about poor people here, about renters at the bottom of society – they have to deal with a shameful lack of social housing. We are talking about educated people here, with a job and a decent income. Isn’t it insane that they can’t find anywhere to live? Young people can never start their adult lives this way” (Truijens, Citation2022).

The idea that housing problems of the young and middle classes play a central role in housing crisis narratives is also forwarded by all three interviewed journalists. In elaborating on their argument, they reflected on their own middle-class position and that of their colleagues and social networks:

“It started to hit the people from the higher classes, although of course in a very minimal way. […] Nowadays every month I will get a message in my [newspaper] mailbox from a colleague whose child is going to study in Amsterdam or has to leave their room, asking if anyone please has a tip [for a room]. That wasn’t the case six years ago. The pain that comes with this, is now much more felt” (interviewed housing journalist #2).

“Maybe it doesn’t mean much, but people my age generally live royally or comfortably. But what I increasingly notice over the last couple of years, is that they worry about their children. That their children will need decent housing too. If my observation stands for more, then that is perhaps the moment the housing crisis got through to ‘our kind of people’. I of course belong to the generation and social standing that has influence on public debate. People in their forties, fifties or sixties’” (interviewed housing journalist #3).

The middle-class bias allows different stakeholders with different interests to rally behind the frame, also in an effort to defend status-quo interests, essentially representing an attempt at (again) depoliticizing the crisis. One telling example is that market players such as developers, investors, lobby groups and interest organizations also expressed sympathy for the housing protests. In response to the Amsterdam housing protest, the Homeowner Association for example published a short video in which they commented (Vereniging Eigen Huis, Citation2021, author translation):

“The Netherlands has entered an unprecedented housing crisis. It is understandable that after so many years people are taking to the streets again for a good and affordable home. The Homeownership Association is strongly committed to providing more homes, for both young and old, so the housing market gets moving again and more people have a chance of finding a suitable home.”

Here we see that the housing crisis frame can be mobilized in such a way that it seeks to reinstate the “dream” of homeownership (also Norris & Lawson, Citation2023), as part of a long-dominant ideology of homeownership (Ronald, Citation2008). This move allows market actors with vested interests and incumbent politics to coopt housing crisis rhetoric in such a way that it supports market-friendly policy solutions that do not require constructing affordable social housing, abolishing tax breaks for affluent homeowners or, more broadly, reimagining the housing system. This move should be considered part of a broader frame forwarded by developers, investors, lobby organizations and market-liberal political parties in which they recognize the housing crisis and seek to put blame on regulations restricting market players from addressing the housing crisis, a narrative that seeks to return to previous frames centered on housing shortages due to a lack of supply.

5. Conclusion

This paper has traced and unraveled the emergence of a national housing crisis in Dutch public and political debate as housing struggles expanded to ever larger segments of the population. It shows how housing crisis narratives have expanded, in frequency as well as what it is deemed to encapsulate. Housing crisis frames have increasingly come to recognize a diversity in outcomes and experiences, while also underscoring the structural causes and political roots of the crisis – thus moving away from technocratic narratives that focus on tweaking the status quo. At the same time, and potentially counterbalancing the previous point, this paper identifies a strong representation of middle-class problems and interests, which may potentially translate into prioritizing middle-class solutions as well. By way of conclusion, I draw some broader points of discussion from the analyses that, I argue, also hold relevance to other contexts and further conceptual debates around how housing crisis frames are constructed, transformed, adapted and mobilized by different actors and over time.

First, the findings of this paper point to a politicization of the housing crisis in public and political debates. This stands in contrast to previous studies highlighting how state and market actors appropriate housing crisis frames to depoliticize housing struggles and forward technocratic, market-oriented reforms (Heslop & Ormerod, Citation2020; White & Nandedkar, Citation2021). While such tendencies are certainly also important in the Dutch case, politicization has been dominant.

In understanding these dynamics, this paper underscores the importance of temporal dynamics of politicization. As the housing crisis incubated, developed and escalated, debates also evolved (see Boin et al., Citation2020). Initially discussions and accompanying frames were rather narrow, largely bracketing the scope for debate to supply and demand issues, which also restricts the scope for imaginable solutions. But as the housing crisis further escalated – brought into focus by the housing protests – the crisis situation became broadly acknowledged. This gave rise to competing frames interpreting the crisis’ complex and political roots. These frames alternatively seek to politicize the housing crisis to spark systemic change, or depoliticize it to minimize change and protect status quo interests. Moving beyond the particularities of the Dutch case, these findings point to the relevance of crisis literature (e.g. Boin et al., Citation2009, Citation2020; Drennan et al., Citation2014) to understand the emergence of various competing frames in which different actors are responsibilized for the housing crisis, and different solutions are rendered imaginable, desirable or necessary. The analyses presented here certainly underscore the importance of homeowning majorities (Ansell, Citation2014; André & Dewilde, Citation2016) and powerful actors with vested interests that seek to reproduce the status quo (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; Nethercote, Citation2022), but also highlight the scope for competing frames.

Second, the paper has highlighted the position of class and age in framing the housing crisis. Relatively much attention was directed towards the housing concerns of young adults and middle-income groups, even if the housing crisis has graver implications for other, more disadvantaged groups. The focus on young adults and on the archetype of the “average” middle-income household suggests a common experience that eschews fundamental class inequalities (also Van Eijk, Citation2013). This is in line with previous studies which have noted that the framing of the housing crisis as a generational issue ultimately obscures the persistent class inequalities that belie them (McKee, Citation2012; Christophers, Citation2018; Howard et al., Citation2024).

This brings us to a tension: on the one hand public and political debates around the Dutch housing crisis have been subject to politicization. Emerging housing movements and other societal actors have been important in popularizing frames pertaining to the right to housing that is not being met and housing as a site for care and solidarity through non-market based social relations (Fields et al., Citation2023; Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; Pattillo, Citation2013). On the other hand, the strong focus on middle-class housing struggles in debates hints at depoliticization. The skewed focus can allow status-quo actors such as incumbent politics, think tanks and influential market players to forward incremental reforms which may alleviate (some) middle-class struggles but do little to help more disadvantaged populations. For example, a focus on the middle-class experience will likely reinforce the “ideal” of homeownership (Norris & Lawson, Citation2023), e.g. by fueling the owner-occupied market through tax breaks and mortgage credit while encouraging the further privatization, debasement and residualization of social housing (Musterd, Citation2014; Slater, Citation2018; Van Gent & Hochstenbach, Citation2020). The tension between politicization and depoliticization also points to the importance of taking a dynamic approach to understand how political and public understandings of housing problems evolve, rather than static interpretations.

Third, the findings hold relevance for the political economy of housing more broadly. Ample research in this field have studied how housing positions specifically tenure and (un)affordability, shape individuals’ voting preferences (Ansell, Citation2014; André & Dewilde, Citation2016; Ansell & Cansunar, Citation2021). Other studies take a more macro approach, to understand, for example, how middle-class ideologies centered around private ownership and capital accumulation permeate political ideologies and manifestos (Ronald, Citation2008; Kohl, Citation2020) and subsequently shape and maintain housing policies (Aalbers, Citation2016; Adkins et al., Citation2021; Stellinga, Citation2022). The present paper, additionally, points to the importance of considering the dynamics of ongoing public and political debates in shaping our understanding of housing crises from a political economy perspective. These debates can shift towards more politicized and fundamental understandings of housing, even without the support of electoral majorities or powerful vested interests.

This paper asked how the housing crisis actually became a housing crisis in public and political debates. Rather than only focusing on housing outcomes themselves, it is also imperative to study these debates themselves. This is crucial because questions such as how the housing crisis is framed, by whom, where and when are crucial in understanding which measures, or solutions, will be taken into consideration. Its findings are a plea to take into consideration framing processes alongside analyses of the actually-existing housing exclusions and injustices at the heart of contemporary housing crises across countries.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Wouter van Gent for his help as well as the REFCOM-research group at Leuven University where an early version of this paper was presented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cody Hochstenbach

Cody Hochstenbach is Assistant Professor in urban geography at the University of Amsterdam. His research focuses on the political economy of housing and socio-spatial inequalities, drawing on a range of quantitative and qualitative methods.

Notes

1 These documents can be accessed via the government website https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/uitgebreidzoeken/parlementair

2 The newspaper database can be accessed via Nexis Uni: https://www.lexisnexis.nl/research/nexis-uni.

3 At the time of writing, the video can be found on YouTube: Regulatory change creates opportunities in Dutch residential, Minister Stef Blok (Real Asset Live TV, June 2014).

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2016) The Financialization of Housing: A Political Economy Approach (Milton Park, Abingdon: Taylor & Francis).

- Aalbers, M. B., Hochstenbach, C., Bosma, J. & Fernandez, R. (2021) The death and life of private landlordism: How financialized homeownership gave birth to the buy-to-let market, Housing, Theory and Society, 38, pp. 541–563.

- Adkins, L., Cooper, M. & Konings, M. (2021) Class in the 21st century: Asset inflation and the new logic of inequality, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53, pp. 548–572.

- André, S. & Dewilde, C. (2016) Home ownership and support for government redistribution, Comparative European Politics, 14, pp. 319–348.

- Ansell, B. (2014) The political economy of ownership: Housing markets and the welfare state, American Political Science Review, 108, pp. 383–402.

- Ansell, B. & Cansunar, A. (2021) The political consequences of housing (un)affordability, Journal of European Social Policy, 31, pp. 597–613.

- Arundel, R. (2017) Equity inequity: Housing wealth inequality, inter and intra-generational divergences, and the rise of private landlordism, Housing, Theory and Society, 34, pp. 176–200.

- Bartels, V. (2018) Woonagenda blijkt na halfjaar wassen neus, Telegraaf, 12 October, pp. 25.

- Benford, R. D. & Snow, D. A. (2000) Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment, Annual Review of Sociology, 26, pp. 611–639.

- Boelhouwer, P. & Priemus, H. (2014) Demise of the Dutch social housing tradition: impact of budget cuts and political changes, Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 29, pp. 221–235.

- Boesveldt, N. F. & Loomans, D. (2023) Housing the homeless: Shifting sites of managing the poor in the Netherlands, Urban Studies, Online First. doi: 10.1177/00420980231208624

- Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P. & McConnell, A. (2009) Crisis exploitation: political and policy impacts of framing contests, Journal of European Public Policy, 16, pp. 81–106.

- Boin, A., Ekengren, M. & Rhinard, M. (2020) Hiding in plain sight: Conceptualizing the creeping crisis, Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 11, pp. 116–138.

- Boterman, W. & Van Gent, W. (2023) Making the Middle-class City. The Politics of Gentrifying Amsterdam (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Brill, F. & Durrant, D. (2021) The emergence of a build to rent model: the role of narratives and discourses, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 53, pp. 1140–1157.

- Byrne, M. & Norris, M. (2022) Housing market financialization, neoliberalism and everyday retrenchment of social housing, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54, pp. 182–198.

- Card, K. (2022) From the streets to the statehouse: how tenant movements affect housing policy in Los Angeles and Berlin, Housing Studies, pp. 1–27. Online First. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2124236

- Cats, R. (2017) Stef blok: ‘ik ben de eerste VVD’er die een heel ministerie heeft doen verdwijnen!, Het Financieele Dagblad, 6 October 2017.

- CBS (2023b) Voorraad woningen en niet-woningen; mutaties, gebruiksfunctie, regio (Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek).

- CBS (2023a) Bestaande koopwoningen; verkoopprijzen prijsindex 2015 = 100 (Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek).

- CBS (2023c) Voorraad woningen; eigendom, type verhuurder, bewoning, regio (Den Haag: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek).

- Christophers, B. (2018) Intergenerational inequality? Labour, capital, and housing through the ages, Antipode, 50, pp. 101–121.

- Couzy, M. (2017) De stad als probleem, de stad als oplossing, Het Parool, 7, pp. 2017.

- Crouch, C. (2009) Privatised keynesianism: an unacknowledged policy regime, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 11, pp. 382–399.

- De Jong, Y. (2022) Nieuwbouw daalt in woningcrisis; Opnieuw minder vergunningen afgegeven, Telegraaf, 18 augustus.

- Drennan, L. T., McConnell, A. & Stark, A. (2014) Risk and crisis management in the public sector (Milton Park: Routledge).

- Dunleavy, P. (1979) The urban basis of political alignment: Social class, domestic property ownership, and state intervention in consumption processes, British Journal of Political Science, 9, pp. 409–443.

- Entman, R. M. (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm, Journal of Communication, 43, pp. 51–58.

- Fairclough, N. (1992) Discourse and Social Change (Cambridge: Policy Press).

- Fields, D., Power, E. R. & Card, K. (2023) Housing movements and care: Rethinking the political imaginaries of housing, Antipode, 56, pp. 743–754.

- Florida, R. (2017) The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class-and What We Can Do About It (New York: Hachette UK).

- Forrest, R. & Hirayama, Y. (2018) Late home ownership and social re-stratification, Economy and Society, 47, pp. 257–279.

- Foye, C. (2022) Framing the housing crisis: How think-tanks frame politics and science to advance policy agendas, Geoforum, 134, pp. 71–81.

- Gargard, C. (2021) Pas nu de woningnood ook de gegoede burgerij raakt, is er protest. NRC, 22 September 2021.

- Giger, N., Rosset, J. & Bernauer, J. (2012) The poor political representation of the poor in a comparative perspective, Representation, 48, pp. 47–61.

- Gilens, M. & Page, B. I. (2014) Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens, Perspectives on Politics, 12, pp. 564–581.

- Giugni, M. G. (1998) Was it worth the effort? The outcomes and consequences of social movements, Annual Review of Sociology, 24, pp. 371–393.

- Goffman, E. (1974) Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (Harvard: Harvard University Press).

- Harvey, D. (1974) Class-monopoly rent, finance capital and the urban revolution, Regional Studies, 8, pp. 239–255.

- Hastings, A. (2000) Discourse analysis: what does it offer housing studies?, Housing, Theory and Society, 17, pp. 131–139.

- Herweijer, K. (2023) De wooncrisis speelde al lang, maar kwam in beeld toen de middenklasse geen huis vond, Algemeen Dagblad, 27 November 2023.

- Heslop, J. & Ormerod, E. (2020) The politics of crisis: Deconstructing the dominant narratives of the housing crisis, Antipode, 52, pp. 145–163.

- Hochstenbach, C. (2022a) Landlord elites on the Dutch housing market: Private landlordism, class, and social inequality, Economic Geography, 98, pp. 327–354.

- Hochstenbach, C. (2022b) Uitgewoond: Waarom het hoog tijd is voor een nieuwe woonpolitiek (Amsterdam: Das Mag).

- Hochstenbach, C. (2023) Balancing accumulation and affordability: How Dutch housing politics moved from private-rental liberalization to regulation, Housing, Theory and Society, 40, pp. 503–529.

- Hoekstra, J. (2017) Reregulation and residualization in Dutch social housing: a critical evaluation of new policies, Critical Housing Analysis, 4, pp. 31–39.

- Howard, A., Hochstenbach, C. & Ronald, R. (2024) Understanding generational housing inequalities beyond tenure, class and context, Economy and Society, 53, pp. 135–162.

- Jacobs, A. M., Matthews, J. S., Hicks, T. & Merkley, E. (2021) Whose news? Class-biased economic reporting in the United States, American Political Science Review, 115, pp. 1016–1033.

- Jacobs, K., Atkinson, R. & Warr, D. (2022) Political economy perspectives and their relevance for contemporary housing studies, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 962–979.

- Jessop, B. (2013) Recovered imaginaries, imagined recoveries: A cultural political economy of crisis construals and crisis-management in the North Atlantic financial crisis. In: Benner, M. (Ed). Before and Beyond the Global Economic Crisis: Economics, Politics, and Settlement, pp. 234–255 (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

- Kadi, J., Hochstenbach, C. & Lennartz, C. (2020) Multiple property ownership in times of late homeownership: a new conceptual vocabulary, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 6–24.

- Kingdon, J. W. (1993) How do issues get on public policy agendas, Sociology and the Public Agenda, 8, pp. 40–53.

- Kohl, S. (2020) The political economy of homeownership: a comparative analysis of homeownership ideology through party manifestos, Socio-Economic Review, 18, pp. 913–940.

- Lievisse Adriaanse, M. (2021) ‘Zelfs met een goede baan geen huis’; Voor veel jongeren is een woning onbereikbaar. NRC, 13 September 2021.

- Madden, D. & Marcuse, P. (2016) In Defense of Housing (London: Verso).

- Marcuse, P. (2009) From critical urban theory to the right to the city, City, 13, pp. 185–197.

- Martínez, M. A. & Gil, J. (2022) Grassroots struggles challenging housing financialization in Spain, Housing Studies, pp. 1–21. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2036328

- Matthews, J. S., Hicks, T. & Jacobs, A. M. (2021) The news media and the politics of inequality in advanced democracies, Draft Paper, Unequal Democracies Seminar.

- McKee, K. (2012) Young people, homeownership and future welfare, Housing Studies, 27, pp. 853–862.

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations (2018a) Nationale Woonagenda 2018-2021 (Den Haag: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations).

- Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations (2018b) The Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (Den Haag: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations).

- Muller, M. & Timmer, E. (2021) Markerwaard krijgt steun, Telegraaf, 24 August, pp. 6.

- Musterd, S. (2014) Public housing for whom? Experiences in an era of mature neo-liberalism: The Netherlands and Amsterdam, Housing Studies, 29, pp. 467–484.

- Nethercote, M. (2022) The post-politicization of rental housing financialization: News media, elite storytelling and Australia’s new build to rent market, Political Geography, 98, pp. 102654.

- Norris, M. & Lawson, J. (2023) Tools to tame the financialisation of housing, New Political Economy, 28(3) pp. 363–379.

- Obbink, H. (2022) De Jonge wil een omslag in het woonbeleid: minstens 30 procent sociale huur, Trouw, 11 May 2022.

- Pattillo, M. (2013) Housing: Commodity versus right, Annual Review of Sociology, 39, pp. 509–531.

- Piketty, T. (2014) Capital in the 21st Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

- Preece, D. V. (2009) Dismantling Social Europe: The Political Economy of Social Policy in the European Union (Boulder, CO: First Forum Press).

- Rex, J. & Moore, R. S. (1967) Race, Community and Conflict: A Study of Sparkbrook (London: Oxford University Press).

- Ronald, R. (2008) The Ideology of Home Ownership: Homeowner Societies and the Role of Housing (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

- Ronald, R., Lennartz, C. & Kadi, J. (2017) What ever happened to asset-based welfare? Shifting approaches to housing wealth and welfare security, Policy & Politics, 45, pp. 173–193.

- Rosenthal, U., Boin, R. A. & Comfort, L. K. (2001) The changing world of crisis and crisis management. In: Rosenthal, U., Boin, R.A. & Comfort, L.K. (Eds) Managing Crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities, pp. 5–27 (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas).

- Ryan-Collins, J. & Murray, C. (2021) When homes earn more than jobs: the rentierization of the Australian housing market, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 1888–1917.

- Ryan-Collins, J. (2018) Why Can’t You Afford a Home? (Cambridge: Polity Press).

- Saunders, P. (1984) Beyond housing classes: the sociological significance of private property rights in means of consumption, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 8, pp. 202–227.

- Schakel, W. (2021) Unequal policy responsiveness in The Netherlands, Socio-Economic Review, 19, pp. 37–57.

- Schumaker, P. D. (1975) Policy responsiveness to protest-group demands, The Journal of Politics, 37, pp. 488–521.

- SCP (2017) Sociale staat van Nederland 2017 (Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau).

- Slater, T. (2018) The invention of the ‘sink estate’: Consequentiategorizationion and the UK housing crisis, The Sociological Review, 66, pp. 877–897.

- Smith, S. J., Clark, W. A., Ong ViforJ, R., Wood, G. A., Lisowski, W. & Truong, N. K. (2022) Housing and economic inequality in the long run: the retreat of owner occupation, Economy and Society, 51, pp. 161–186.

- Smithuijsen, D. (2021) Ook met een jubelton op zak kun je het vergeten op de amsterdamse woningmarkt, Het Parool, 10 September 2021.

- Stellinga, B. (2022) Housing financialization as a self-sustaining process. Political obstacles to the de-financialization of the Dutch housing market, Housing Studies, 39, pp. 877–900.

- Telegraaf (2021) Woningnood, newspaper editorial, April 17.

- Tolfo, G. & Doucet, B. (2021) Gentrification in the media: the eviction of critical class perspective, Urban Geography, 42, pp. 1418–1439.

- Truijens, A. (2022) De modale werknemer kan nergens meer wonen, en dat is krankzinnig, Volkskrant, August 22.

- Tweede Kamer (2017) Vragen van het lid Kops (PVV) aan de Minister van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties over het bericht «dat het woningtekort nijpend wordt» (ingezonden 14 juli 2017) (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal).

- Tweede Kamer (2018) Integrale visie op de woningmarkt (13 maart 2018), 32847 nr. 332 (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal).

- Tweede Kamer (2019a) Maatregelen middenhuur (11 April 2019) (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal).

- Tweede Kamer (2019b) Vaststelling van de begrotingsstaten van het Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties (VII) voor het jaar 2020 (10 December 2019) (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal), 35300 VII.

- Tweede Kamer (2021a) Integrale visie op de woningmarkt. Verslag van een commissiedebat (7 October 2021) (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal), 32847–816.

- Tweede Kamer (2021b) Vragenuur: Vragen Beckerman (14 September 2021) (Den Haag: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal), h-tk-20202021-105-4.

- Van den Dool, P. (2018) ‘Reddingsplan’ voor huizenmarkt. NRC Handelsblad, 24 May 2018, p. 2.

- Van Dooremalen, T. & Uitermark, J. (2021) The framing of 9/11 in American, French, and Dutch national newspapers (2001–2015): An inductive approach to studying events, International Sociology, 36, pp. 464–488.

- Van Eijk, G. (2013) Hostile to hierarchy? Individuality, equality and moral boundaries in Dutch class talk, Sociology, 47, pp. 526–541.

- Van Gent, W. & Hochstenbach, C. (2020) The neo-liberal politics and socio-spatial implications of Dutch post-crisis social housing policies, International Journal of Housing Policy, 20, pp. 156–172.

- Van Gent, W., Damhuis, R. & Musterd, S. (2023) Gentrifying with family wealth: Parental gifts and neighbourhood sorting among young adult owner-occupants, Urban Studies, 60, pp. 3312–3335.

- Van Hulst, M. & Yanow, D. (2016) From policy “frames” to “framing”: theorizing a more dynamic, political approach, The American Review of Public Administration, 46, pp. 92–112.

- Vereniging Eigen Huis (2021) Reactie op het woonprotest, 8 September, Online: https://www.eigenhuis.nl/woningmarkt/woonprotest#/

- Vereniging Eigen Huis (2023) 10 maart: zet je tent op en scoor je LL23 ticket! Newsletter, 24 January. https://www.eigenhuis.nl/huis-kopen/starters/in-actie-voor-starters/manifestatie-starters#/

- Vols, M. (2022) Het recht op huisvesting en de Nederlandse Grondwet, Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor De Mensenrechten, NTM/NJCMbull, 2022/11.

- Waldron, R. (2023) Generation rent and housing precarity in ‘post crisis’ Ireland, Housing Studies, 38, pp. 181–205.

- Watt, P. & Minton, A. (2016) London’s housing crisis and its activisms: Introduction, City, 20, pp. 204–221.

- Wetzstein, S. (2017) The global urban housing affordability crisis, Urban Studies, 54, pp. 3159–3177.

- White, I. & Nandedkar, G. (2021) The housing crisis as an ideological artefact: Analysing how political discourse defines, diagnoses, and responds, Housing Studies, 36, pp. 213–234.