ABSTRACT

Emotional intelligence training intervention was used to reduce tobacco smoking consumption among school-going adolescents in state of Edo, Nigeria. The pre-test post-test experimental design was observed. While the 90 participants were purposively selected from the schools that were randomly assigned to EIT (45) and control groups (45). Analysis of covariance and independent t-tests were used for data analysis. The emotional intelligence training intervention significantly improved tobacco smoking cessation of school-going adolescents with pre-test and post-test mean scores of 33.12 (33.12%) and 21.25 (21.25%), respectively. The participants exposed to EIT (Mean = 21.25; SD = 2.68) gained more those in the control group (Mean = 42.79; SD = 14.21). The interaction effect of the treatment and sex was also significant. Conclusively, the emotional intelligence training intervention was effective in tobacco smoking cessation among school-going adolescents, though cessation response could be sex-dependent.

Introduction

It is a well-known fact that tobacco smoking is one of the avoidable causes of ill-health, disabilities and premature death worldwide. Despite its deadly tendencies, associated health hazards and an annual global death rate of over seven million (Action on Smoking and Health; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2017), tobacco smoking has continued to gain more popularity among young adults, especially with the advent of e-cigarettes (Alexander et al., Citation2001; West, Citation2017). Even though most smokers acknowledge the negative consequences of smoking, they regrettably continue to smoke, a behaviour that defies rational explanation (West, Citation2017). However, West and Shiffman (Citation2016), averred that strong urges to smoke can be traced to the nicotine contained in tobacco, which often makes smokers ignore its negative consequences. In addition to the nicotine component in tobacco, it also contains a large number of toxic substances, with about 7357 chemical compounds with addictive chemicals (Tun et al., Citation2017). According to Action on Smoking and Health (2016b), lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and coronary heart disease are smoking-related causes of death, while the US Department of Health and Human Services (Citation2004) pointed that tobacco smoking is the main risk factor for back pain, deafness, blindness, osteoporosis and peripheral vascular disease – causing amputation and strokes.

In spite of the increased risk factor associated with mental health problems, including depression and psychiatric disorders, tobacco smoking remains a major public health concern (Jamal et al., Citation2017; McKelvey & Ramo, Citation2018; Singh et al., Citation2016) because the majority of smokers begin in adolescence (Bhaskar et al., Citation2016; Lim et al., Citation2010; World Health Organization, Citation2008). Adolescence is a critical period of transition from childhood to adulthood and it is characterized by rapid physical, cognitive emotional and social development (Alsubaie, Citation2018). Given the unique biological, psychological/emotional, and social features of adolescents with the desire for autonomy, exploration/experimentation is most prominent at this stage, thus leading to involvement in many risky or unhealthy behaviours including tobacco smoking, risky sex and illicit drug use as well as alcoholism (Alsubaie, Citation2018; Meader et al., Citation2016). Evidence abounds that tobacco consumption among adolescents is influenced by several factors, such as individual, economic, environmental, psychological and social. At this stage, the individual adolescent is preoccupied with acceptance by peers and society, therefore increased rates of tobacco consumption are eminent (Gordon & Flanagan, Citation2016; Islam et al., Citation2016).

Many countries around the world have made concerted efforts by enforcing and implementing tobacco product regulation Acts, which prohibit public advertisement of the product on any national media platforms in reducing smoking prevalence, and have recorded significant progress (Gowing et al., Citation2015; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Nevertheless, WHO (Citation2011) estimated that over eight million tobacco-related deaths are likely to be recorded per year by 2030. The prevalence of tobacco consumption among adolescents in developing countries is of great concern, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Hussain & Satar, Citation2013), like Nigeria (Itanyi et al., Citation2018). According to a report by the American Cancer Society (Citation2018), p. 25,000 children and adolescents between the ages of 10- and 14-years smoke cigarettes each day. Similarly, an earlier report by the Global Youth Tobacco Survey of Nigeria established that one-in-five in school adolescents aged 13–15 years had ever attempted tobacco smoking, and about one-in-ten are currently smoking (Aniwada et al., Citation2018; Ekanem et al., Citation2010). More recently, the African Tobacco Control Alliance (Citation2020) lamented the increased risk of tobacco smoking among school-going adolescents in Nigeria, which includes cancers of almost all organs of the body, central nervous system, heart and respiratory system (Itanyi et al., Citation2020).

Itanyi et al. (Citation2020) attributed the high prevalence of tobacco consumption among adolescents in Nigeria to relaxed regulations on the control of the tobacco products by the Nigerian government. For instance, despite the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Acts, Article 16 of which Nigeria is a signatory, tobacco is still being sold in single sticks which makes it affordable for the majority of adolescents. Previous studies have had advanced strategies to reduce tobacco smoking among school-going adolescents, such as school-based programmes that involved peer-led social influence and social competence training (Georgie et al., Citation2016), educational programmes (Thomas et al., Citation2013), mass media campaigns (Brinn et al., Citation2012), and increasing the financial cost of smoking (Van Hasselt et al., Citation2015). Notwithstanding these preventative measures, tobacco smoking rates among adolescents remain relatively high (Hammond, Citation2005; Hill & Maggi, Citation2011), possibly due to psycho-cognitive interventions, such as cognitive behaviour, rational emotive behaviour, psycho-education, contingency management, self-control, cognitive-behavioural interventions and emotional intelligence therapies (Stead & Lancaster, Citation2005) among others have not been used in reducing tobacco smoking among school-going adolescents. This study therefore desired to examine if emotional intelligence therapy has any impact in reducing tobacco smoking consumption among selected in-school adolescents.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence (EI) gained recognition among researchers over a decade ago, giving its variety of positive effects on human functioning and potential to improve and maintain positive health (Dev et al., Citation2018; Roxana Dev et al., Citation2014). Being a protective construct, emotional intelligence was described by Salovey and Mayer (Citation1990) as the ability to discriminate, monitor and use information about one’s emotions to guide one’s thought processes and behaviours. Emotional intelligence involves mainly an individual’s achievement, adaptability, emotional self-awareness, empathy, mood-regulation/self-control, self-assessment, self-evaluation, cognitive competence, conceptual thinking, problem-solving, and stress management (Bar-On, Citation2001; Hill & Maggi, Citation2011; Goleman, Citation2002). Li et al. (Citation2009) opined that EI is a psychological mechanism capable of enhancing positive behavioural changes. Similarly, the protective potential of EI encompasses both intrapersonal and interpersonal measures against the initiation of smoking (Bar-On, 2006). Thus, EI is the ability to cope with negative emotions and discourage the dependence on self-medication with substances, such as alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco for emotional regulation (Hill & Maggi, Citation2011; Kun & Demetrovics, Citation2010; Trinidad et al., Citation2004). In this study, emotional intelligence was adopted as a psycho-emotional intervention to demotivate tobacco use among school-going adolescents. Furthermore, the justification for the choice of EI as an intervention in this study is premised on its possibility to identify and appropriately manage undesirable adolescents’ peer pressure to smoke (Trinidad et al., Citation2004).

What does literature say about emotional intelligence and smoking behaviour?

It has been established that emotional intelligence plays a significant role in tobacco use. For instance, Trinidad and Johnson (Citation2002) found a negative relationship between emotional intelligence and self-reported tobacco use among students; in that students with low EI had tendencies of greater tobacco smoking frequency (i.e. daily, weekly smoking, and number of cigarettes in the past 30 days). In a similar study by Trinidad et al. (Citation2004), early adolescents with high EI are more likely to have greater confidence to refuse a cigarette and a lower chance of continued smoking. An investigation on the perceived EI and tobacco use among university students in Spain was conducted by Limonero et al. (Citation2006), it was found that emotional regulation plays a preventative role against tobacco use. In an interventional study by Fletcher et al. (Citation2009), EI training was also found to effectively and significantly improve the communication skills of 36 randomly selected third year medical students in the United Kingdom. Other previous studies have also shown similar findings of higher EI being associated with lower smoking frequency, an earlier initial smoking age (Kun & Demetrovics, Citation2010), an increased awareness of the negative consequences of smoking and the increased likelihood of refusing cigarette offerings from peers (Perea-Baena et al., Citation2011)

Furthermore, Ciarrochi et al. (Citation2011) affirmed that emotional intelligence training has an impact on psychological health; emotional intelligence can effectively facilitate the adequate adjustment of individuals in situations. Karimzadeh et al. (Citation2012) examined the effectiveness of EI on general health in a training programme, which lasted 10 weeks and 10 sessions. Findings indicated that participants in the EI training group had a better chance of good general health than those in the control group. Louie et al. (Citation2006) established the effectiveness of emotional components, which includes self-control and self-awareness in reducing destructive behaviour among adolescents. Hill et al. (Citation2011) assessed the association of the five components of emotional intelligence and smoking among adolescents. The five dimensions include adaptability, general mood, intrapersonal, interpersonal and stress management competencies. They used self-reported smoking to classify participants’ smoking into three categories, being daily, occasional or non-smokers. The outcome of the study revealed that emotional intelligence was effective in reducing smoking frequency from daily to occasional. The study concludes that emotional intelligence should be considered in smoking prevention programmes.

In Nigeria, Bisji, et al. (Citation2019) investigated the impact of emotional intelligence training on secondary school adolescents’ mental health in the Jos South LGA of Plateau State. Forty-eight adolescents voluntarily participated in the study and were grouped into experimental and control groups. The treatment lasted six sessions of training involving intensive emotional-social intelligence skills acquisition for 1 month. Findings showed that participants in the experimental group had scored higher on emotional intelligence than those in the control group. The study suggests that adolescents with higher emotional intelligence have the potential to refuse and eschew mental health. More recently, Megías-Robles et al. (Citation2020) studied the preventative role of EI in smoking relapse after a year of cessation. The study participants comprise of 173 volunteer established smokers. Findings established that individuals with lower emotional repair abilities were associated with a higher likelihood of relapse. Furthermore, emotional clarity and repair abilities moderated the indirect effect of nicotine dependence on smoking relapse through the influence of stress reactivity. Consequently, West (Citation2017) suggested the need for psychological interventions as methods to combat the prevalence of tobacco-related harm and to reduce it. Despite the rate of tobacco use and its health-related risks and consequences to the adolescents who are the future of any nation, few studies have paid attention to the intervention tendencies of emotional intelligence in reducing tobacco smoking among secondary school-going adolescents in Nigeria hence justification for this study.

Aim

The main concern of this present study was to examine the effectiveness of emotional intelligence training (EIT) in reducing tobacco smoking consumption among school-going adolescents in selected secondary schools in Edo State, Nigeria.

Research questions

The study addressed the following;

Was there any significant effect of emotional intelligence training on tobacco smoking consumption in school-going adolescents?

Was the interaction effect of treatment based on sex significant on tobacco smoking consumption among school-going adolescents?

Method

Design and participants

The study design was a quasi-experimental which compared two groups, an intervention group and a control group, while data was collected using the quantitative method. Two secondary schools were randomly selected from the public senior secondary schools in the Oredo Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. Adopting a randomization procedure, to screen the participants, the Kim’s Smoking Cessation Motivation Scale (KSCMS) by Park, et al. (Citation2009) was used. A total of 90 school-going adolescents which score above 31 on the KSCMS (where scores from 1–15 = low motivation to smoke, 16–30 = moderate motivation to smoke and 31–50 = high motivation to smoke). There were 45 participants in the intervention group (18 males and 27 females) with a mean aged of 13.5 (12 and 15 years). Eighteen were without fathers, thirteen had both parents, nine were without mothers and five were without both parents. With regards to religion, 32 were Christian while 13 were Muslim.

There were also 45 participants in the control group (20 males and 25 females), their average age (mean = 13.5) (12 and 15 years). Twelve of which were without fathers, sixteen had both parents, twelve were without mothers and seven were orphans. With regards to religion, 36 were Christian, while 9 were Muslim. Overall, 90 school-going adolescents participated in the study.

Procedure

The researchers obtained permission from the state ministry of education in Edo State and were introduced to the principals of the two selected schools, the principal investigators were also counselling therapists with PhDs in counselling and developmental psychology. The research lasted six sessions for those who were exposed to Emotional Intelligence Training. The interest of the participants was sustained throughout the training period by providing light refreshments. However, the same pre-test and post-test instruments were administered to the two groups.

Participation criteria

Participation was voluntary and the following criterion were met:

School-going adolescents who smoke or have smoked in the last one week

School-going adolescents who signed the consent form.

Adolescents who enrolled in a public secondary school in the selected local government.

School-going adolescents whose age ranged 12 and 15 years of age (Teipel, Citation2013).

Instrument

Adolescents’ tobacco smoking was measured using the Global Youths Tobacco Survey (GYTS) Core Questionnaire version 1.2 developed by the World Health Organization (Citation2020). It is a 43 itemed standardized self-report survey developed for youths consisting of four sections including socio-demographic characteristics, use of smoked and smokeless tobacco, and susceptibility to smoking initiation. Also, the Kim’s Smoking Cessation Motivation Scale (KSCMS) by Park, et al. (Citation2009) was used as a screening tool. The scale consisted of 10 items that focus on pre-contemplation, contemplation and preparation designed in a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 5 (Strongly Disagree). To avoid the effects of random responses, items seven, eight and ten were scored in reverse order.

Intervention group: EIT

The aim of the training: The aim of emotional intelligence training is to assist school-going adolescents cope with negative emotions, improve and maintain positive health by decreasing dependence on self-medication with substances, such as tobacco, while group counselling approach was used in each session lasting 45 min.

Session 1: Orientation, familiarization and pre-test scores data collection.

Session 2: Explanation of tobacco use, the associated health risks and the consequences for adolescents.

Session 3: Discussion of coping with negative emotions/feelings and self-assessment or self-evaluation.

Session 4: Discussion of emotional self-awareness and mood-regulation/self-control.

Session 5: Training on cognitive competence, conceptual thinking, problem-solving, and stress management.

Session 6: The previous sessions revised, post-test data collection and conclusion.

Control group

Participants in this group were not exposed to any intervention but were observed for the same period of 6 weeks during their normal classroom activities. The pre-test data was equally collected and at the end of the session post-test data was also gathered.

Analysis of data

Data gathered was analysed using an independent t-test analysis (t-test) and an analysis of variance (ANCOVA), at a level of 0.05 significance to determine the effectiveness of the training on the dependent variable (tobacco smoking). The degrees of the mean scores of the participants in the intervention and control groups were ascertained by Fishers’ LSD post-hoc analysis.

Ethical statements

Ethical protocols were duly observed since it is the morality of the research. Based on the international ethics of research, the authors assured the participants that the confidentiality of the information gathered is guaranteed. They were also informed that their participation is voluntary, which means that they were free to opt out at will. The authors also assured the participants that the information gathered would be used for research purposes only.

Results

The first research question’s intention was to discover if emotional intelligence training was effective on the tobacco smoking consumption of school-going adolescents. The finding in showed the significant main effect of intervention on tobacco smoking. The independent t-test of sample pre-tests and post-tests as indicated in has shown that the mean score for smoking was 33.12 (33.12%), after intervention it was only 21.25 (21.25%). By implication there was a significant decrease in tobacco smoking consumption in the intervention group. Thus, emotional intelligence training is effective in reducing tobacco smoking consumption among school-going adolescents. Furthermore, the result in has shown the mean and standard deviation in tobacco smoking consumption scores of school-going adolescents exposed to EIT and those in the control group. The participants in the EIT (Mean = 21.25; SD = 2.68) achieved well than those in the control group (Mean = 42.79; SD = 14.21) who were not trained. This implies that participants in the EIT programme benefited more than their foils who were engaged in their normal daily school activities, which is proved by the low mean score gotten from the participants in the control group.

Table 1. Summary T-test of paired sample pre-test and post-test tobacco smoking scores in managing tobacco smoking of participants exposed to EIT

Table 2. Summary of mean and standard deviation in tobacco smoking scores of school-going adolescents exposed to EIT and those in the control group at post-test

Research question two anticipated the significant interaction effect of treatment according to sex on tobacco smoking among school-going adolescents.

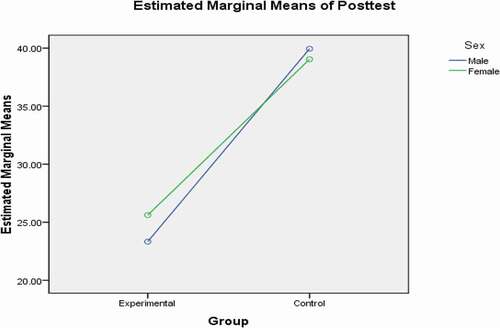

As seen in , the interaction effect between the treatment and sex was somewhat significant on tobacco smoking (F1, 88 = 3.995, p < 0.05; p = 0.047). This means that there was a significant interaction between sex and treatment impacting the tobacco smoking scores when comparing the results pertaining to each sex. Additionally, below provides a graphical illustration of the interaction effect between males and females in their response to the treatment. It is evident that the male participants in the experimental group benefited more than their female counterparts in the same experimental group. This implies that the treatment is more effective for males than it is for females.

Table 3. Summary of ANCOVA of Post-test score on the tobacco smoking of the participants

Discussion of the findings

The concern of this study was to investigate the effect of emotional intelligence training on tobacco smoking consumption among school-going adolescents. The result of the study attested to the fact that the desire to use tobacco could be discouraged with the effective use of emotional intelligence training, just like other therapeutic interventions, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, rational emotive behaviour therapy, narrative therapy, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), desensitization and reprocessing, psychoeducation, and supportive therapy. Therefore, adolescents’ motivation to use tobacco stems from peer influence, low self-esteem, stress, school factors, risky behaviours, parental socio-economic status, parental smoking and weight control (Du et al., Citation2010; Pénzes et al., Citation2012) which could be managed with emotional intelligence training. Moreover, emotional intelligence training is among intervention-based approaches that could be used to promote the cessation of tobacco usage or smoking among school-going adolescents. This finding therefore upholds previous studies (Ciarrochi et al., Citation2006; Hill et al. 2018; Kun & Demetrovics, Citation2010; Louie et al., Citation2018; Megías-Robles et al., Citation2020; Perea-Baena et al., 2011). In particular, Megías-Robles et al. (Citation2020) found that EI training is capable of reducing nicotine dependence and can ultimately lead to the cessation of tobacco use, even when stressed. As defined earlier, emotional intelligence involves an individual’s ability to control and regulate his/her emotions/moods/feelings, thought process and be aware of other peoples’ emotions (Salovey & Mayer, Citation1990). A person with a high level of emotional intelligence has a capacity for conceptual thinking, cognitive competence, self-evaluation, problem-solving and stress management (Bar-On, 2001, 2006; Hill & Maggi, Citation2011; Goleman, Citation2002).

The outcome of the current study further revealed that the interaction effect of emotional intelligence and sex was somewhat significant. This means that the effectiveness of emotional intelligence training could, to some extent, vary by sex. This was further confirmed in , which showed that the male participants performed better than the female in their response to the treatment. This outcome is no surprise, as in a modern society, such as this, everyone seems attracted to and celebrates individuals with thin bodies, and it is widely believed that smoking is an effective weight control strategy since cigarettes contain anorectics (Pénzes et al., Citation2012). Individuals, females in particular, are particular about their bodily changes, especially during adolescence, and are preoccupied with acceptance by their peers and society (Gordon & Flanagan, Citation2016; Islam et al., Citation2016). Thus, studies have shown that adolescent girls are motivated to consume tobacco because of the socio-cultural pressures to be thin (Currie et al., Citation2001; Du et al., Citation2010), as female adolescents perceive themselves as being overweight and are dissatisfied with their body image. Therefore, they often result to tobacco consumption as a strategy for weight control to achieve their desired body shape (Pénzes et al., Citation2012). The motivation to quit smoking through EIT can therefore be more effective in male adolescents compared to female adolescents, as shown in this current study.

Conclusion

The concern of this study was to explore the effectiveness of emotional intelligence training in tobacco smoking consumption cessation among school-going adolescents. This concern is premised on the public health efforts to ensure tobacco smoking consumption cessation among adolescents (Sarna et al., Citation2013; Struik et al., Citation2014). Being a factorial quasi-experimental design, a pre-test and post-test control group was adopted to purposively group 90 school-going adolescents who volunteered to participate in a six-week treatment programme, with the exception of the control group who received no treatment. This study concluded that emotional intelligence training intervention was effective in tobacco smoking cessation among school-going adolescents. Furthermore, the motivation to quit tobacco smoking was found to be, to some extent, sex dependent. Therefore, emotional intelligence training is among few interventions that have targeted adolescents’ tobacco smoking consumption cessation and if effectively applied may ultimately increase tobacco smoking cessation success rates among youths. The treatment and sex were also found to be significant, which implies that tobacco smoking cessation intervention such as emotional intelligence training among adolescents could be sex dependent.

Limitations

The primary concern of this study was on school-going adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15 years. Therefore, adolescents who have not enrolled in any secondary school, either public or private, were not recruited even though they also may smoke or use tobacco. Given the nature of this study, which only permitted two secondary schools of the Oredo Local Government Area in Edo State, the generalization of the study was limited. This study was limited to emotional intelligence training alone, whereas the combination of two interventions could possibly be better, and a comparison could be drawn.

Recommendations and suggestion for further studies

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are imperative as public health could adopt emotional intelligence training in enhancing adolescents’ ability to quit tobacco smoking and it could improve healthy behaviours for better living and economic development. This cessation interventional approach is germane to impacting the school-going adolescents to consciously reconstruct their thinking pattern, promote social participation, develop a positive self-image, boost their self-esteem, increase academic performance and develop emotional functioning. Counsellors and social psychologists could employ emotional intelligence training individually or jointly to help clients at risk of tobacco health hazards. Considerations should also be given to the sex differences when tobacco smoking cessation intervention is being employed.

It is suggested that the replication of this study elsewhere should be welcomed. This may validate and further establish the findings of this research. The researchers suggest a further extension of the scope to include larger samples and additional interventions. It is suggested that the study also be carried out in other states in Nigeria to broaden the generalizations of this study. Finally, it is suggested that future studies could consider parental and adult smoking in order to ensure continuity and reinvigoration of training in public health efforts to achieve tobacco smoking cessation.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contribution of all adolescents who volunteered to participants in this study by patiently undergone the six session training programme and responding to the questionnaire distributed to them and returned.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declare no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this work is not available publicly but could be provided by the author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kehinde Clement Lawrence

Dr Kehinde Clement Lawrence obtained his Doctoral degree in Counselling and Developmental Psychology in 2019 from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He is currently a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Educational Psychology and Special Education at the Faculty of Education, University of Zululand. His research bias is educational, counselling and developmental antecedents and behavioural consequences of children/adolescents and late adulthood, their psychosocial development as well as general well-being, and he has published several articles and book-chapters in peer-reviewed Scopus and World of Science journals. He is co-supervising masters and Ph.D research projects in area of educational psychology.

Elizabeth Osita Egbule

Dr Egbule Elizabeth Osita is a Senior lecturer in the Department of Guidance and Counseling, Delta state University Abraka. Nigeria, where she also obtained her Doctoral degree in 2017. She has published several articles and book chapters in accredited peer - reviewed journals in different areas of Educational, Counseling and Socio personal counseling. Within and outside Nigeria. She is co- supervising masters and PhD research projects in areas of Guidance and Counseling .

References

- African Tobacco Control Alliance. The sale of single sticks of cigarettes in Africa. https://atca-africa.org/en/the-saleof-single-sticks-of-cigarettes-in-africa. Accessed January 20, 2020.

- Alexander, C., Piazza, M., Mekos, D., & Valente, T. (2001). Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00210-5

- Alsubaie, A. S. R. (2018). Prevalence and determinants of smoking behavior among male school adolescents in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 32(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0180

- American Cancer Society. Vital Strategies. The Tobacco Atlas: [Nigeria Fact Sheet]. https://files.tobaccoatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/nigeria-country-facts-en.pdf Accessed November 2, 2018

- Aniwada, E. C., Uleanya, N. D., Ossai, E. N., Nwobi, E. A., & Anibueze, M. (2018). Tobacco use: Prevalence, pattern, and predictors, among those aged 15-49 years in Nigeria, a secondary data analysis. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 16, 07. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18332/tid/82926

- Bar-On, R. (2001). Emotional intelligence and self-actualization. In J. Ciarrochi, J. P. Forgas, & J. D. Mayer (Eds.), Emotional intelligence in everyday life: A scientific inquiry (pp. 82–97). Psychology Press.

- Bhaskar, R. K., Sah, M. N., Gaurav, K., Bhaskar, S. C., Singh, R., Yadav, M. K., & Ojha, S. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use among adolescents in the schools of Kalaiya, Nepal: A cross-sectional questionnaire based study. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 14(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12971-016-0075-x

- Bisji, J. S., Ogbole, A. J., & Umar, S. J. (2019). Emotional intelligence among Nigerian adolescents: the role of training. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry,10(5), 191–195. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aboh-Ogbole/publication/348230802_Emotional_intelligence_among_Nigerian_adolescents_the_role_of_training/links/5ff41bbd299bf14088703411/Emotional-intelligence-among-Nigerian-adolescents-the-role-of-training.pdf

- Brinn, M. P., Carson, K. V., Esterman, A. J., Chang, A. B., & Smith, B. J. (2012). Cochrane review: Mass media interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Evidence-based child health. A Cochrane Review Journal, 7, 86–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1808

- Ciarrochi, J., Kashdan, T. B., Leeson, P., Heaven, P., & Jordan, C. (2011). On being aware and accepting: A one-year longitudinal study into adolescent well-being. Journal of adolescence, 34(4), 695-703. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.09.003

- Ciarrochi, J. E., Forgas, J., & Mayer, J. D. (2006). Emotional intelligence in everyday life. Psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

- Currie, C., Roberts, C., Morgan, A., Smith, R., Settertobulte, W., Samdal, O., & Rasmussen, V. B. (2001). Young people’s health in context: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. International Report from the, 2002.

- Du, H., van der, A., . D. L., Boshuizen, H. C., Forouhi, N. G., Wareham, N. J., Halkjær, J., Tjønneland, A., Overvad, K., Jakobsen, M. U., Boeing, H., Buijsse, B., Masala, G., Palli, D., Sørensen, T. I., Saris, W. H., & Feskens, E. J. (2010). Dietary fiber and subsequent changes in body weight and waist circumference in European men and women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91(2), 329–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28191

- Ekanem, I. A., Asuzu, M. C., Anunobi, C. C., Malami, S. A., Jibrin, P. G., Ekanem, A. D., … Anibueze, M. (2010). Prevalence of tobacco use among youths in five centres in Nigeria: A global youth tobacco survey (GYTS) approach. Journal of Community Medicine and Primary Health Care, 22, 1–2.

- Fletcher, I., Leadbetter, P., Curran, A., & O'Sullivan, H. (2009). A pilot study assessing emotional intelligence training and communication skills with 3rd year medical students. Patient education and counseling,76(3), 376–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.019

- Georgie, J. M., Sean, H., Deborah, M. C., Matthew, H., & Rona, C. (2016). Peer-led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11-21 years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 111(3), 391–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13224

- Goleman (2002). Emotional intelligence, social intelligence, ecological intelligence. New york: Bantam books.

- Gordon, P., & Flanagan, P. (2016). Smoking: A risk factor for vascular disease. Journal of Vascular Nursing, 34(3), 79–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvn.2016.04.001

- Gowing, L. R., Ali, R. L., Allsop, S., Marsden, J., Turf, E. E., West, R., & Witton, J. (2015). Global statistics on addictive behaviours: 2014 status report. Addiction, 110(6), 904–919. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12899

- Hammond, D. (2005). Smoking behaviour among young adults: beyond youth prevention. Tobacco control,14(3), 181–185. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2004.009621.

- Hill, E. M., & Maggi, S. (2011). Emotional intelligence and smoking: Protective and risk factors among Canadian young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(1), 45-50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.008

- Hussain, H. Y., & Satar, B. A. A. (2013). Prevalence and determinants of tobacco use among Iraqi adolescents: Iraq GYTS 2012. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 11(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1617-9625-11-14

- Islam, S. M. S., Mainuddin, A. K. M., Bhuiyan, F. A., & Chowdhury, K. N. (2016). Prevalence of tobacco use and its contributing factors among adolescents in Bangladesh: Results from a population-based study. South Asian Journal of Cancer, 5(4), 186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/2278-330X.195339

- Itanyi, I. U., Onwasigwe, C. N., McIntosh, S., Bruno, T., Ossip, D., Nwobi, E. A., Onoka, C. A., & Ezeanolue, E. E. (2018). Disparities in tobacco use by adolescents in southeast, Nigeria using Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) approach. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5231-1

- Itanyi, I. U., Onwasigwe, C. N., Ossip, D., Uzochukwu, B. S., McIntosh, S., Aguwa, E. N., … Ezeanolue, E. E. (2020). Predictors of current tobacco smoking by adolescents in Nigeria: Interaction between school location and socioeconomic status. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5231-1

- Jamal, A., Gentzke, A., Hu, S. S., Cullen, K. A., Apelberg, B. J., Homa, D. M., & King, B. A. (2017). Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(23), 597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6623a1

- Karimzadeh, M., Goodarzi, A., & Rezaei, S. (2012). The effect of social emotional skills training to enhance general health& Emotional Intelligence in the primary teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 57-64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.068

- Kun, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2010). Emotional intelligence and addictions: a systematic review. Substance use & misuse, 45(7-8), 1131-1160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903567855

- Lancaster, T., & Stead, L. F. (2005). Self‐help interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane database of systematic reviews, (3). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001118.pub2

- Lawrence Dev, R. D. O., Kamalden, T. F. T., Geok, S. K., Abdullah, M. C., Ayub, A. F. M., & Ismail, I. A. (2018). Emotional Intelligence, Spiritual Intelligence, SelfEfficacy and Health Behaviors: Implications for Quality Health. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences,8(7), 794–809. doi:https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i7/4420.

- Li, G. S. F., Lu, F. J., & Wang, A. H. H. (2009). Exploring the relationships of physical activity, emotional intelligence and health in Taiwan college students. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness,7(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1728-869X(09)60008-3

- Lim, K. H., Sumarni, M. G., Kee, C. C., Christopher, V. M., Noruiza Hana, M., Lim, K. K., & Amal, N. M. (2010). Prevalence and factors associated with smoking among form four students in Petaling District, Selangor, Malaysia. Tropical Biomedicine, 27(3), 394–403. https://msptm.org/files/394_-_403_Lim_KH.pdf

- Limonero, J. T., Tomás-Sábado, J., & Fernández-Castro, J. (2006). Perceived emotional intelligence and its relation to tobacco and cannabis use among university students. Psicothema, 18, 95–100. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72709514.pdf

- Louie, A.K., Coverdale, J. & Roberts, L.W. Emotional Intelligence and Psychiatric Training. Acad Psychiatry 30, 1–3 (2006). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.30.1.1

- Louie, A.K., Coverdale, J.H., Balon, R. et al. Enhancing Empathy: a Role for Virtual Reality?. Acad Psychiatry 42, 747–752 (2018). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-018-0995–2

- McKelvey, K., & Ramo, D. (2018). Conversation within a Facebook smoking cessation intervention trial for young adults (Tobacco status project): Qualitative analysis. JMIR Formative Research, 2(2), e11138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/11138

- Meader, N., King, K., Moe-Byrne, T., Wright, K., Graham, H., Petticrew, M., Power, C., White, M., & Sowden, A. J. (2016). A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3373-6

- Megías-Robles, A., Perea-Baena, J. M., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2020). The protective role of emotional intelligence in smoking relapse during a 12-month follow-up smoking cessation intervention. PloS one, 15(6), e0234301. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234301

- Park, J. W., Chai, S., Lee, J. Y., Joe, K. H., Jung, J. E., & Kim, D. J. (2009). Validation study of Kim's smoking cessation motivation scale and its predictive implications for smoking cessation. Psychiatry investigation, 6(4), 272. doi:https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2009.6.4.272.

- Pénzes, M., Czeglédi, E., Balázs, P., & Foley, K. L. (2012). Factors associated with tobacco smoking and the belief about weight control effect of smoking among Hungarian adolescents. Central European Journal of Public Health, 20(1), 11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a3726

- Perea-Baena, J. M., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Oña-Compan, S. (2011). Depressive mood and tobacco use: Moderating effects of gender and emotional attention. Drug and alcohol dependence, 119(3), e46-e50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.029

- Preventing Tobacco use among young people: A report of the surgeon general (Executive summary), MMWR 43(RR-4);1-10; Centers for disease control and prevention. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/prevguid/m0030927/M0030927.asp [ Last accessed on 2017 June 13].

- Roxana Dev, O. D., Ismi Arif, I., Maria Chong, A., & Soh Kim, G. (2014). Emotional intelligence as an underlying psychological mechanism on physical activity among Malaysian adolescents. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 19, 166–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i7/4420.

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

- Sarna, L., Bialous, S. A., Chan, S. S. C., Hollin, P., & O’Connell, K. A. (2013). Making a difference: Nursing scholarship and leadership in tobacco control. Nursing Outlook, 61(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2012.05.007

- Singh, T., Arrazola, R. A., Corey, C. G., Husten, C. G., Neff, L. J., Homa, D. M., & King, B. A. (2016). Tobacco use among middle and high school Students — United States, 2011–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65(14), 361–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1

- Struik, L. L., O’Loughlin, E. K., Dugas, E. N., Bottorff, J. L., & O’Loughlin, J. L. (2014). Gender differences in reasons to quit smoking among adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing, 30(4), 303–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840513497800

- Teipel, K. (2013). Understanding adolescence. Seeing through a developmental lens. A synthesis of adolescent development research conducted at University of Minnesota. Association of Maternal Camp.

- Thomas, R. E., McLellan, J., & Perera, R. (2013). School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Evidence-based Child Health. A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(5), 1616–2040. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1937

- Trinidad, D. R., & Johnson, C. A. (2002). The association between emotional intelligence and early adolescent tobacco and alcohol use. Personality and individual differences,32(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00008-3

- Trinidad, D. R., Unger, J. B., Chou, C. P., & Johnson, C. A. (2004). The protective association of emotional intelligence with psychosocial smoking risk factors for adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences,36(4), 945–954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00163-6

- Tun, N. A., Chittin, T., Agarwal, N., New, M. L., Thaung, Y., & Phyo, P. P. (2017). Tobacco use among young adolescents in Myanmar: Findings from global youth tobacco survey. Indian Journal of Public Health, 61(5), 54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_236_17

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (2004). The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General.

- van Hasselt, M., Kruger, J., Han, B., Caraballo, R. S., Penne, M. A., Loomis, B., & Gfroerer, J. C. (2015). The relation between tobacco taxes and youth and young adult smoking: What happened following the 2009 U.S. federal tax increase on cigarettes? Addictive Behaviors, 50(1), 253-272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.023

- West, R. (2017). Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & Health, 32(8), 1018–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1325890

- West, R., & Shiffman, S. (2016). Fast facts:smoking cessation. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers.

- World Health Organization. (2008). MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic.

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011: Warning about the dangers of tobacco. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44616/1/9789240687813_eng.pdf. Accessed on October 12, 2017.

- World Health Organization. 2013. Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training: World Health Organization guidelines 2013. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/93635/9789241506502_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization. Media Centre. Fact sheet, 2017. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/ Accessed on October 12, 2017

- World Health Organization. 2020. Summary results of the global youth tobacco survey in selected countries of the WHO European Region (No. WHO/EURO: 2020-1513-41263-56157). World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.