ABSTRACT

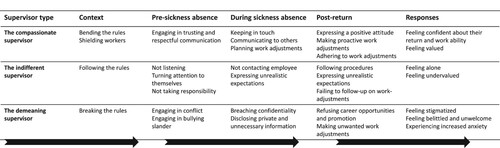

Supervisors play an important role in supporting employees to return to work following sickness absence due to common mental disorders; stress, anxiety and depression, however, employees may not always feel supported. We examined employees’ perceptions of their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours pre, during and following sickness absence due to common mental disorders, placing a particular focus on post-return. In a qualitative study, using purposeful sampling, we recruited and interviewed 39 returned employees up to four times. We identified three types of supervisor behaviours: the compassionate, the indifferent and the demeaning. Compassionate supervisors possessed empathy and communication skills, worked collaboratively to identify appropriate work adjustments and provided ongoing support and adjustment. Indifferent supervisors lacked the skills and motivation to support returning employees. They did what was required according to organisational policies. Demeaning supervisors lacked understanding and displayed stigmatising behaviour. The results extend our understanding of how supervisors may support returned employees in two ways: First, our results identified three distinct sets of supervisor behaviours. Second, the results indicate that it is important to understand return to work as lasting years where employees are best supported by supervisors making adjustments that fit the needs of returned employees on an ongoing basis.

The prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs), such as stress, anxiety, and depression, is high. In the OECD countries, it is estimated that approximately 15% of employees suffer from CMDs (OECD, Citation2014). For approximately half of this group, long-term sickness absence is the consequence (OECD, Citation2014). Mental health in the workplace is costly. A recent report revealed that in the UK, mental health issues cost UK employers £34.9 billion; the breakdown of these costs were: £10.6 billion due to sickness absence, £21.2 billion due to presenteeism (working while ill) and £3.1 billion were due to employees leaving employment due to mental health issues (Parsonage & Saini, Citation2017). CMDs are more prevalent and more easily adjustable for in the workplace than more severe illnesses, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (OECD, Citation2014). Previous research has found that supervisors play an important role in supporting employees with mental health problems return to work as they are the main point of contact during sick leave and play a key role in agreeing work adjustments at the point of re-entry to work (Aas et al., Citation2008; Joosen et al., Citation2021; Munir et al., Citation2012). A recent survey revealed that 84% of supervisors are aware of their impact on their employees’ mental health (BITC, Citation2019).

Most return to work (RTW) research has focused on how to return to work; less attention has been paid to understanding what happens once the employee has returned (Nielsen et al., Citation2018), nor has there been much focus on adverse supervisor behaviours. Hees et al. (Citation2012) found that supervisors, occupational physicians and employees agreed that sustainability is key to a successful RTW. There is therefore a need to understand the factors that help employees stay and thrive at work post-return. In this paper, we present the results of a qualitative interview study of employees who have returned after long-term sickness absence due to a CMD. We explore returned employees’ experiences of their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours pre, during and following sickness absence, but with a particular focus on the period post-return.

The present study adds to the current knowledge on employees’ experiences of how supervisor attitudes and behaviours may facilitate or hinder the RTW journey for employees returning after long-term sickness absence due to common mental disorders in two ways. First, we focus on the post-RTW journey of employees who return after sick leave due to CMDs. Tjulin et al. (Citation2010) divided the RTW journey into three phases. The first phase, pre-return refers to the period where employees are off due to their condition. The second phase, re-entry, refers to the phase where plans are made to support the employees’ return to work and work adjustments are agreed, e.g. phased return. In the third phase, sustainable phase, the employees have returned and strive to stay in work; during this phase they may continue to work reduced hours.

In a review of stakeholders’ role and actions in the RTW journey, Corbière et al. (Citation2020) identified 131 references to managers in relation to RTW for workers with CMDs, however, many of these were not empirical studies, and few of the empirical studies focused directly on the supervisor and even fewer on the behaviours of supervisors in the sustainable phase. Corbière et al. (Citation2020) concluded that supervisors in the sustainable phase should arrange regular follow-up meetings with employees to ensure work accommodations remain fit for purpose and to communicate any changes to colleagues. These conclusions seemed to be drawn based on best policy recommendations rather than empirical research. There is therefore a need to take a step back to understand how returned employees experience their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours in the sustainable phase.

A growing body of the literature shows that relapse is high among returned employees. One study found that almost one in five returned employees experienced relapse due to CMDs over a seven-year period (Koopmans et al., Citation2011), mostly within three years of initial return. Norder et al. (Citation2015) found that more than three quarters of returned employees relapsed over a period of ten years. Exploring the long-term consequences of sickness absence due to CMDs, Norder et al. (Citation2017) found that nearly one in four employees left employment post-return, of whom a quarter resigned, just under a third were laid off, another 31% retired early, and 6% were granted disability pension. In the literature, sustainable return to work has been operationalised as a relatively short period, i.e. three months after return, with little consideration for what happens after the individual returns (Etuknwa et al., Citation2019). There is therefore good reason to develop our understanding of what happens once employees have returned as they readjust to work.

Second, the existing literature primarily focuses on the positive role and actions of managers and supervisors (Corbière et al., Citation2020), however, in the wider occupational health psychology literature, reviews have concluded that both passive and active forms of supervisors’ negative behaviours can have a detrimental impact on follower wellbeing (Fosse et al., Citation2019; Schyns & Schilling, Citation2013). We, therefore, applied an open approach to the attitudes and behaviours of supervisors to understand how employees who have returned to work experienced their supervisors and their reactions to such attitudes and behaviours.

As there has been little focus on SRTW and the broader range of supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours, not just supportive behaviours, we conducted a descriptive study using semi-structured interviews with returned employees to gain insights into returned employees’ reality, including both positive and negative experiences of their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours in relation to the management of the RTW journey. Qualitative methods enable us to explore employees’ own accounts of how their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours have hindered or facilitated their SRTW journey.

Supervisors’ support for initial return to work for employees with CMDs

As highlighted above, only few qualitative studies have focused explicitly on supervisors’ support for the employee during the sickness absence period. Studies have found that employees and supervisors have reported that effective communication, ability to manage privacy and disclose reasons for sickness absence to colleagues, ability to establish trust, being understanding and approachable, knowledge of organisational policies, and ability to develop work adjustments were important in the sickness absence and re-entry phases of RTW (Johnston et al., Citation2015; Joosen et al., Citation2021; Munir et al., Citation2012; Negrini et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, Aas et al. (Citation2008) identified 78 supervisor qualities and seven supervisor types that supported employees’ return, which were classified as protectors, encouragers, problem-solvers, contact-makers, trust creators, recognisers, and responsibility makers (offensive and direct supervisors).

Common symptoms of CMDs include lack of concentration, poor memory, anxiety in social contexts and problems making decisions (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and reduced work functioning is prevalent, even after remission (Norder et al., Citation2017). Therefore, understanding how employees experience supervisors as either supporting or hindering their ability to stay and thrive at work, manage symptoms, and navigate the post-return journey with reduced work functioning in the longer term is important. Corbière et al. (Citation2021) explored the strategies needed to support employees with CMDs during sick leave, re-entry and the sustainable phases. Key stakeholders, including three supervisors, were interviewed. These supervisors reported that a good relationship was key to monitoring returned employees’ recovery and work functioning. Lemieux et al. (Citation2011) found that in the sustainable phase, supervisors reported managing workloads ensuring that employees were stimulated, but not overwhelmed. Other studies have found that employees generally reported little support from supervisors post-return (Noordik et al., Citation2011; Ståhl & Stiwne, Citation2014) with few exceptions such as continuous meetings and allowing the employee to set their own pace (Ståhl & Stiwne, Citation2014). Neither of the studies on the sustainable phase focused explicitly on the supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours and the knowledge is therefore limited.

There has been limited focus on the negative attitudes and behaviours of supervisors. Ladegaard et al. (Citation2019) found that supervisors’ attitudes towards employees on sick leave was that stress equated to being busy and being busy does not make you ill. Supervisors also attributed sick leave to individual characteristics rather than because of work. Although supervisors were interviewed 12 months later, there was little focus on the post-return period (Ladegaard et al., Citation2019). Munir et al. (Citation2012) identified a few negative behaviours which prevented RTW, such as supervisors losing patience with employees, making them feel like a nuisance, engaging in aggressive actions, questioning the behaviours of employees, and going against work adjustments. Importantly, Munir et al. (Citation2012) found supervisors lacked knowledge and skills to determine which work accommodations could be implemented. Together these studies provide valuable insights into the behaviours that help employees return, however, post-return different behaviours are needed as supervisors need to manage returned employees considering their work functioning on a day-to-day basis.

A common characteristic of these studies is the limited attention paid to the sustainable phase and the limited focus on detrimental supervisor behaviours. In the UK Health and Safety Executive guidelines for managing RTW, the focus is on the absence and re-entry phases (https://www.hse.gov.uk/sicknessabsence/) stating that organisations should develop policies for RTW, keep in contact with their employees on sick leave and considering work adjustments upon return. No mention is made of the role of the supervisor, and organisations are not required to develop policies for the sustainable phase.

In the present study, we employ an open approach to exploring how employees who have returned to work after long-term sickness absence due to stress, anxiety and/or depression have experienced the attitudes and behaviours of their supervisor(s) either supporting or hindering their RTW. We focus primarily on the sustainable phase of RTW.

Method

Participants

Using purposeful sampling (Palinkas et al., Citation2015), we recruited 39 participants. The inclusion criteria were employees who had been off for at least three weeks, who had been diagnosed with either stress, anxiety and/or depression and were off sick for this reason. All participants were based in the UK. Returned employees had been back between one month and 96 months with an average of 12 months (SD = 21.79). Returned employees were employed in administration (26%), managerial roles (26%), education and research (15%), police (15%), information technology (8%), health (5%), consultancy (3%) and manual labour (3%). The mean age of the sample was 46 (SD 8.47, range 29–62), 21 (54%) were female and 18 (46%) were male.

Procedure

We recruited returned employees through social media; LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter, a large public sector organisation and through charities and occupational health services supporting employees with CMDs, advertising for employees who had returned to work after sickness absence due to CMDs. As is common in the UK we focused on stress, anxiety and depression (https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/mental-health.htm). We recruited broadly to ensure a diversity of experiences. We conducted one-to-one semi-structured interviews with supervisors. We continued recruiting participants until data saturation was reached (Clarke & Braun, Citation2014). Five interviews were conducted face to face, the remainder were telephone interviews enabling us to recruit all over the UK. We based our pre-constructed interview guide on a review of the RTW literature, employing an open-ended approach to identify supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours. Interviews were conducted by five trained occupational psychologists with extensive experience conducting semi-structured interviews and researching RTW, participants were interviewed by the same occupational psychologist throughout each time point to ensure consistency. A training session took place to ensure consistent probing and interviewing among interviewers. Interviewers made notes of their reflections of each interview, and these were discussed in the team and considered in analyses. No interviewers had prior relationships with the returned employees.

To get an in-depth understanding of how employees’ perceptions of supervisors’ consistency of behaviours, we interviewed employees up to four times, at various time points, once a month. We originally planned four interviews with each employee, however, some employees did not respond to subsequent emails to set up further interviews or indicated that they did not feel they had more to add after the first interview. All 39 employees who approached us met the inclusion criteria and were interviewed at least once. Twenty-one returned employees were interviewed four times, two completed three interviews, five were interviewed twice and 11 were interviewed once. We interviewed employees over the phone or face-to-face all over the UK. The study was approved by the University of the Lead Author’s Ethics Committee. The participants received information about the study together with their rights and signed a written consent form that outlined their rights and emphasised confidentiality. Each participant was allocated a code including a random participant number and which month they were interviewed (e.g. P4-M4).

Returned employees reported having had up to three different supervisors during their RTW journey; 30% reported having had the same supervisor, 61% reported having two supervisors (two of these were shared line management), and 9% had had three supervisors. In these cases, we coded which supervisor the experience related to, e.g. 1st supervisor. In semi-structured interviews, we asked returned employees about their RTW journey and their experiences with their immediate line managers which are the supervisors we focus on in this study. In the first interview, we asked about the situation before sickness absence, the absence and re-entry phases. We then asked employees to describe their experiences of post-return. In subsequent interviews, we asked about their experiences in the past month. In each interview, we asked specifically about the supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours.

Time 1 interviews lasted between 20 and 97 min, average = 54 min, SD = 17.53. At time 2, interviews lasted between 8 and 62 min with an average of 28 min (SD = 13.96). Time 3 interviews lasted between 13 and 66 min, with an average of 31 min (SD = 14.27). Finally, time 4 interviews lasted between 13 and 67 min, with an average of 34 min (SD = 15.11). All interviews bar two were recorded, in these cases, the participants did not consent to the interview being recorded but agreed to comprehensive notes being taken during the interview. Data were transcribed verbatim and coded in NVivo to facilitate analysis.

Analytic strategy

We conducted thematic analysis in six steps (King, Citation2004). In the first step, we familiarised ourselves with the data; reading and rereading the transcripts and taking initial notes. In the second step, we coded the data according to attitudes and behaviours. We applied an inductive approach. We identified 205 “thought units,” phrases or sentences, relating to supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours. In the third step, we discussed the coded thought units and identified themes. In addition to the attitudes and behaviours of supervisors, employees also mentioned that supervisors operated within a context and we added this as a separate theme. In total, we identified 14 subthemes. We then classified subthemes into three overarching categories (themes): positive experiences with the supervisor, the experiences of lack of support from the supervisor and the negative experiences with the supervisor. Finally, we mapped the onto the RTW journey to elucidate differences between the types of supervisor attitudes and behaviours at the pre-return, re-entry and sustainable phases, however, we did not find any differences over time. In the fourth step, the first author revisited the data to ensure that our themes were representative of the experiences of returned employees. In the fifth step, we defined and named the overall themes. We discussed the themes in terms of labels and allocation of thought units to codes and through discussion reached agreements of what the labels would be. We termed our overall themes compassionate, indifferent and demeaning supervisory behaviours. For each of the subthemes, we mapped these onto a cluster across the three types of supervisory behaviour. In the final step, we wrote up the analyses in three parts; a descriptive text summarising the codes and themes, a table summarising the themes and subthemes, and tables with representative codes. Full information of tables can be found in FigShare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1.

Results

We identified three overarching themes of supervisor behaviours, which we have termed compassionate, indifferent, and demeaning. In many cases, our returned employees had experienced a change of supervisor and thus they may appear in different categories depending on the supervisor they refer to. provides a summary of the clusters of supervisor behaviours and the subthemes outlining the attitudes and behaviours of these three types of supervisors. For each subtheme, we have listed the matching attitude and behaviours for each subtheme in a cluster. Six subthemes of the compassionate supervisor were identified, however, for two subthemes, continued focus for mental health and ongoing negotiations about flexible work adjustments, no equivalent subthemes were identified for the indifferent and the demeaning supervisor. For an overview of themes including selected representative quotes, see . For a full overview of tables, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1.

Table 1. Short overview of representative quotes.

Compassionate supervisors

We found a cluster of supervisor attitudes and behaviours described by returned employees in positive terms; supervisors were perceived to have provided invaluable support pre, during and post return and in many cases helped them stay in the job and regain their confidence on their return. For detailed qualitative analyses, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1.

Pre-return supportive behaviours

A key characteristic of the compassionate supervisor was a description of a respectful, trusting relationship with their supervisor prior to sick leave. In some cases, the supervisor had detected something was amiss and reached out to the employee. During the sick leave period, employees reported three key elements of the supervisor’s support to be crucial to return. First, returned employees appreciated that supervisors respected their privacy and agreed with them what would be communicated to colleagues and other managers. Second, returning employees reported they felt supported when supervisors listened to their account of their illness without prejudice. Third, returned employees emphasised the importance of good two-way conversation about the return, where supervisors kept an open mind about the work adjustments employees needed.

Positive attitudes towards employees

Returned employees who reported their supervisor was compassionate emphasised the importance of the attitudes towards the returning employee and an understanding of mental health issues post return. Underlying the understanding of mental health issues was that compassionate supervisors often had lived experience, either having suffered from CMDs themselves or had relatives with CMDs. Returned employees felt such supervisors had a deeper level of understanding, and supervisors sharing personal experiences helped build trust. Behaviours relating to building the confidence and feeling of belongingness were also found to be important. Employees reported that compassionate supervisors reinforced that they were seen as valuable employees and a part of the team. A clear demonstration of returned employees’ value to the organisation was to invest in them by sending them on, for example, leadership training or supporting their career progression. Finally, demonstrating trust that the returned employee could complete work to the required standard was also perceived to be important by many.

Proactive support for work adjustments

Employees reported that all important to compassionate supervisors was the RTW conversation, where returned employees discussed and agreed work adjustments with their supervisor. Work adjustments mentioned by employees related to a phased return, i.e. reduced working hours, and a reduction in responsibilities and work tasks. As some employees had been off for a while and new systems and procedures had been introduced, work adjustments could also mean on-the-job refresher training. Many employees said that they had returned to overflowing inboxes. Supervisors who acknowledged that getting started could seem an unsurmountable task and subsequently helped employees to prioritise and redistribute work facilitated employees in regaining their confidence in doing the job and helped them feel valued.

Employees reported that ongoing adjustments were crucial to thriving at work and tasks should only be taken on at a pace employees were comfortable with. For example, the tasks of one employee involved driving, however, prior to sickness absence, driving had been associated with suicidal thoughts and intentionally crashing the car. The employee agreed with the supervisor that driving would not be included as part of their responsibilities until they were ready. Returned employees reported that adherence to agreed work adjustments could be problematic. It was easy to fall into old working patterns and check emails from home or stay late. Compassionate supervisors played a key role in ensuring employees adhered to agreed adjustments by checking up on returned employees and reminding them to adhere to agreed work adjustments.

Continued focus on mental health

Returned employees felt valued when supervisors went above and beyond and were available to listen when employees were struggling, even if this was outside working hours. It was not just about the formal arrangement and work adjustments, other behaviours included checking in regularly and providing informal support and reassurance to employees that they could do the job. Equally important for returned employees was for supervisors to incorporate talking about mental health as part of daily business, encouraging returned employees to be open about issues and offer support if necessary. Employees also reported it was important that supervisors checked up on them after employees had completed a task that they were anxious about or organising for colleagues to support employees with tasks they found challenging.

Returned employees reported, in several cases, that the continued focus on mental health was vital to building their confidence. Many employees described problems concentrating and would panic when having to attend meetings. The acceptance of supervisors of their difficulties and the encouragement and permission to slowly get back into the job was found to be crucial in the sustainable phase.

Ongoing negotiations about flexible working

A common subtheme among employees was the need for flexible working arrangements. The flexible working arrangements meant that compassionate supervisors and employees engaged in ongoing negotiations enabling employees to come in later, leave early, work from home, or work in quieter locations in the workplace on days they were struggling. Supervisors approving employees to take holiday at short notice was also perceived to be important in managing mental health. Other examples of supervisors’ support included postponing processes if returned employees felt overwhelmed, for example performance appraisals.

Bending the rules

Returned employees described the supervisor acting as a buffer against an often-challenging wider context. Employees reported that compassionate supervisors did not operate in a vacuum. They provided examples of how supervisors would go above and beyond and protect their employees in a context that was less supportive of SRTW. Compassionate supervisors would try to shield employees from negative policies or poor leadership from elsewhere in the organisation that threatened their SRTW. For example, where performance pressure was high, employees reported that compassionate supervisors would buffer the pressure despite the pressures supervisors themselves experienced from senior management layers. Consistently, returned employees described how supervisors shielded them from pressures arising from punitive absence regulations. In many organisations, performance procedures were automatically triggered by a certain number of sickness absence days within a limited period, regardless of the reasons for absence. In some cases, holding up the umbrella to shield employees involved making flexible adjustments even when they went against company policy, in other cases finding ways to work around the absence reporting system.

The indifferent supervisors

The second theme of supervisor attitudes and behaviours was described by returned employees as not being intentionally harmful, but lacking understanding and motivation to learn about mental health issues or what was required to support returned employees. These supervisors were absent, provided little support and did only the minimum required. For a detailed analysis, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1.

Pre-return evasion of responsibility

Prior to absence, returned employees reported that indifferent supervisors had shown little understanding of their situation. In many cases, employees had raised issues, but the calls for help had not been acknowledged. In some cases, supervisors had tried to evade responsibility by suggesting the employees sought the support of colleagues. In other cases, indifferent supervisors made a joke of the situation to deflect dealing with the issues. Typical indifferent supervisor behaviours included trying to relate in an unfortunate way and turning the conversation to be about them rather than listening to the challenges faced by the employees. The lack of understanding also characterised the actions of the supervisors during the period where the employees were on sick leave. Supervisors were reported to have been passive during the period the employees were off sick and only made minimal contact to follow organisational procedures and supervisors had avoided discussing personal issues.

Neutral attitudes towards the employees

Supervisors who fell in the indifferent supervisor category were described as having little understanding of what CMDs are and showed little interest in finding out more. The returned employees explained that supervisors made no attempts to understand their situation and translate attitudes into supportive actions and employees as a result felt undervalued.

Basic provision for adjustments

Returned employees perceived that indifferent supervisors made few attempts to make work adjustments. Employees felt that supervisors went through the motions and followed procedures, but did not try understand their needs. Although a phased return was often planned, returned employees found that supervisors had unrealistic expectations of the work they could achieve in the reduced working hours. A related challenge was that in some cases, although a phased return was planned, it was not followed through. Further, employees described that supervisors did not support the prioritisation of what tasks should be completed and therefore returned employees felt alone in navigating the RTW journey.

Following the rules

Returned employees felt indifferent supervisors towed the company line with little consideration for the individual. Some returned employees took this as a sign that supervisors were afraid of not following policies and getting into trouble; others described that the supervisor did not seem to see that supporting the employee’s return was part of their role. In terms of the context, indifferent supervisors would do what was required of them as per company policies but did little to provide real support to their employees.

Demeaning supervisor behaviours

The accounts of what we have chosen to call demeaning supervisors are characterised not only by a lack of compassion, but with bullying, conflicts and not following companies’ return to work policies. Returned employees felt stigmatised and seen as the mental illness rather than as a person. For details of the analysis, see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1.

Pre-return lack of support and bullying

Returned employees reported they had experienced a problematic relationship with their supervisor in the period before sick leave. Relationships had been characterised by conflicts, bullying and slander. Run-ins with, and persistent experiences of being singled out by, the supervisor created anxiety and in some cases were described as the direct cause of the employee’s absence. Employees reported supervisors had spread rumours about them, had excluded them from meetings and had been two-faced, saying one thing but doing another, leaving employees to second guess supervisors’ intentions. An equally difficult relationship was reported during sick leave. Supervisors had openly shared information about the employees’ sick leave and the reasons for sick leave with colleagues and other managers without agreeing with the employee what and how to communicate matters relating to the sick leave; often disclosing sensitive and unnecessary information, sometimes breaching confidentiality.

Unaccommodating attitudes towards employees

Returned employees reported negative attitudes and a lack of compassion. In some cases, where demeaning supervisors had lived experience, these supervisors assumed that what worked for them would work the returned employee and therefore they knew what the returned employee needed. Some supervisors expressed disdain for the additional management load required to support the returned employees, making employees feel belittled and unwelcome. Supervisors demonstrated negative attitudes towards returned employees explaining work practices and procedures in a patronising way or questioning whether employees were even working. Unlike the compassionate supervisors, demeaning supervisors refused to support the returned employee for promotion and competence development, signalling returned employees were not seen as worth investing in.

Implementing counterproductive work adjustments

Returned employees felt that demeaning supervisors made work adjustments without discussion or consent of the returned employee. For example, a police officer was moved to an administrative desk job without consultation, against their explicit wishes. Another reported that a new supervisor they did not know telephoned them just before their return to tell them that they had been replaced with someone who could do a good job, signalling that the returned employee was seen as “damaged goods.” Others reported having been seconded to other parts of the organisation, also without consultation. Those who returned to their original job, reported they were not invited to team meetings and many work tasks were taken from them despite them feeling capable of doing them – and telling their supervisor so. In other cases, work adjustments were refused altogether. Demeaning supervisors did not review work adjustments.

Breaking the rules

Returned employees reported that these supervisors in many cases ignored the advice of occupational health service reviews and did not follow company RTW policy; demeaning supervisors would disregard the rules and norms.

Supervisor’s behaviours and attitudes across the RTW journey

Compassionate, indifferent, and demeaning types of attitudes and behaviours were consistent throughout the RTW journey. Employees describing compassionate supervisors spoke of their trusting working relationship with their supervisor pre-sickness absence, while those employees managed by demeaning supervisors spoke of conflict and bullying. Specific behaviours and actions were evident throughout the absence period and return, leading to employees feeling different about their RTW journey. In some situations, compassionate supervisors navigated absence management systems by bending the rules to shield employees; while in other situations demeaning supervisors disregarded any due process without fear of challenge. summarises the patterns of behaviour in the sustainable phase for the three sets of supervisor attitudes and behaviours.

Discussion

In the present paper, we report the results of the qualitative study exploring how employees who have returned to work after a period of long-term sickness absence due to CMDs experience the attitudes and behaviours of their supervisors. Previous research has identified that supervisors play a key role in supporting employees’ RTW, especially in terms of providing support and ensuring appropriate work adjustments (Aas et al., Citation2008; Munir et al., Citation2012). In our qualitative study, we identified three types of supervisor attitudes and behaviours, each had a very different impact on the returned employees’ experiences of the post-RTW journey. We term these compassionate, indifferent and demeaning supervisors.

Compassionate supervisors go beyond company policy and bend the rules to support returned employees. Returned employees reported that compassionate supervisors built their confidence and helped them feel valued. Indifferent supervisors made employees feel undervalued and alone while demeaning supervisors stripped employees of their dignity and made them feel belittled and unwelcome. Demeaning supervisors made returned employees feel stigmatised and ostracised and, in some cases, exacerbated mental health symptoms as employees ruminated about how to interpret the signals and behaviours of their demeaning supervisor. Our results paint a diverse picture of supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours towards the returned employee with CMDs, from one extreme the supervisor being the reason employees return to work and not only stay at work but also thrive and develop, to the other extreme where the supervisor was the main reason for the employee’s absence and upon return aggravating the anxiety of the returned employee.

We identified supervisory attitudes and behaviours that returned employees felt impacted their mental health and SRTW journey. Despite interviewing employees up to four times, we did not find any longitudinal evidence that employees changed their view of their supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours during the RTW journey. It could be argued that returned employees would either portray their supervisor as the compassionate or demeaning based on their mental state. Almost three quarters of returned employees in our study had changed supervisor during their RTW journey, meaning that many employees had experiences with more than one supervisor, however, employees often rated new supervisors differently.

The RTW journey may be particularly difficult in the early phases, where supervisors in some cases evaded responsibility. It could be said that the more positive views over time could result in better mental health (EMP13, EMP10), but employees described concrete different behaviours so it may either be that new supervisors were better or that it was simply easier to manage employees who had been back for a while. For EMP7 it was the opposite experience: the first manager was compassionate, but the manager that took over later as perceived as indifferent. Together, these reflections on the patterns within the data suggest that there are observable and meaningful differences in the behaviours displayed by compassionate, indifferent and demeaning supervisors.

Overall, our results emphasise the importance of developing a longer-term perspective, understanding the RTW journey as lasting years, not just three months as is often the time span studied in the literature (Etuknwa et al., Citation2019). Our results demonstrate the need for developing our understanding of the impact of supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours on employees’ experience of return to work and the diversity of supervisors’ management of the long-term RTW journey. Thomas and Linstead (Citation2002) argued that it is misleading to paint supervisors as a homogenous entity. Our findings suggest a more nuanced approach is needed and examination of the impact of the three types of supervisory behaviour may help us to better understand the disparity among returners’ work and mental health outcomes. In the following, we discuss our findings in relation to the RTW literature and the literature on leadership.

The RTW journey

Our study contributes to the knowledge on the RTW journey of employees with CMDs in multiple ways. Our results extend the sparse research on supervisors’ negative behaviours during employees’ RTW journey. Aas et al. (Citation2008) reported only the responsibility maker displayed some negative qualities such as being offensive and potentially setting limits and Munir et al. (Citation2012) identified more negative behaviours such as losing patience with employees, making them feel like a nuisance, engaging in aggressive behaviours and not committing to work adjustments. Our results paint a more nuanced picture in that we identified two types of negative supervisory attitudes and behaviours: the indifferent and the demeaning. Our results on the period leading up to sick leave and the off sick and re-entry phases are consistent with the findings of Joosen et al. (Citation2017) who reported that employees reported bullying and poor relationships with supervisors being part of the reasons behind sick leave. In line with Joosen et al. (Citation2017), we also found a nuanced picture of supervisor attitudes and behaviours in during the sick leave and re-entry phases. Supervisors were perceived both to be barriers or facilitators to return depending on whether they were seen to be supportive, accepting and sympathetic or unsupportive, bullying and uncommunicative.

Negrini et al. (Citation2018) found that supervisors who reported a good relationship with their employees during sick leave also reported a good relationship prior to them going on sick leave and maintained frequent contact with employees during sick leave, including making plans for work accommodations. We found the same for employees. Returned employees who reported they had had a good relationship with their supervisor prior to, and during, their sick leave, also reported a good relationship in the sustainable phase. In their interview study, Aas et al. (Citation2008) reported similar qualities to those we found in the compassionate supervisors while employees were on sick leave: empathy, acceptance, listening skills, being appreciative and encouraging. In their interview study of a RTW intervention, Andersen et al. (Citation2014) found that it was crucial to a good process that employees were seen as individuals with unique needs, not just a number or common mental disorder by agents supporting their return. We found similar results in the sustainable phase of the RTW journey.

We extend the Aas et al. (Citation2008) and Munir et al. (Citation2012) studies by exploring the sustainable phase of RTW. It is not only important to agree on work accommodations but also follow up on these and make adjustments to fit the needs of the returned employee as their confidence builds. Supervisors play an important role in confidence building, not only through support and reassurance, but through empowering employees and through the provision of regular feedback. A third theme concerned the flexibility and autonomy afforded to the supervisors themselves; supervisors need decision latitude to allow employees to leave early or come in later, or even taking holiday as short notice. The results extend Joosen et al. (Citation2017) who found supervisory flexibility and autonomy to be important in the earlier phases of the RTW journey. All these factors may enable returned employees to manage their own mental health, but may also reduce additional pressures derived from rigid absence management procedures.

Unlike the findings of Ladegaard et al. (Citation2019), our returned employees did not feel their supervisors saw sick leave as caused by individual characteristics and mental health being a question of being busy, possibly because our broader inclusion of employees with not only stress but also anxiety and depression and the focus on the sustainable phase where employees reported supervisors’ attitudes revolved around their performance.

Our findings emphasise the role of organisational context and the extent to which supervisors can navigate the organisational systems. Employees described very different experiences with the supervisors’ understanding of, and adherence to, their organisations’ absence management policy. Our results align with Ladegaard et al. (Citation2019) who found that those responsible for managing the RTW process feel torn between demands for care and performance and a lack of support from the wider organisation. Our findings suggest that this situation is far from a discrete incident but an ongoing and pervasive experience. Further research would benefit from understanding the impact of ongoing need to navigate rigid systems post return from the perspective of supervisors themselves.

Consideration of the wider leadership literature

In occupational health psychology, it is widely acknowledged that leadership styles, different types of supervisory behaviours, impact employees (Nielsen & Taris, Citation2019). The types of supervisory attitudes and behaviours identified in our study share some resemblances with existing leadership concepts.

Gjerde and Alvesson (Citation2020) found university department heads used the metaphor “umbrella carrier” to describe themselves. Supervisors tried to protect academic staff from the performance pressures and changes from above. They hold up an umbrella and engage in discussions and filtering. In many ways, the compassionate supervisors were described in a similar way. They fought against hostile sickness absence policies and engaged in day-to-day behaviours to build employees’ confidence and help them re-adjust to work. Alvesson and Sveningsson (Citation2003) found that leaders often engaged in informal chats to emphasise they are on equal footing with their employees and to signal that they were available if employees needed to talk to them. We identified similar behaviours in the compassionate supervisors; they regularly talk to their returned employees, dropping by to check whether everything was ok, having informal chats about how the employees were settling in and signalling that they were available to talk if the employee needed them.

In their meta-analysis, DeRue et al. (Citation2011) identified a classification of leadership styles they termed relational leadership behaviours, such as empowering, participative and democratic leadership, and the individualised consideration dimension of transformational leadership. Leaders enacting these relational behaviours are characterised as being friendly and approachable, open to input, showing consideration and care, and treating followers equally. DeRue et al. (Citation2011) found relational leadership behaviours to be related to wellbeing outcomes. Relational behaviours are similar to the behaviours enacted by our compassionate supervisors, and we identified concrete examples of what such behaviours look like in relation to returned employees with particular needs. Returned employees felt that supervisors who understood their specific needs and how these needs change over time helped employees stay and thrive at work. Adjusting work tasks gradually also helped build returned employees’ confidence in themselves and helped them to feel valued.

DeRue et al. (Citation2011) identified what they termed passive leadership, including the management-by-exception dimension of transactional leadership and laissez-faire leadership (Bass & Avolio, Citation1994). These leaders are characterised by being absent and not taking responsibility unless it is absolutely required. Passive leadership is negatively associated with employee wellbeing (DeRue et al., Citation2011; Harms et al., Citation2017). We found our indifferent supervisors fall in this category; they ignored employees’ signs of emerging poor mental health pre-sickness absence and when employees returned, they did little to support them. The indifferent supervisors lack understanding of CMDs symptoms, how these symptoms may influence work functioning and what work adjustments can be made. Laissez-faire leaders are often absent and difficult to get hold of and take no particular interest in their employees (Bass & Avolio, Citation1994). Indifferent supervisors showed little interest in supporting their employees; they were mostly passive and did what organisational policy required of them, but little more. Our research on the indifferent supervisor echoes a concern raised in previous research that supervisors may be ill-equipped and poorly motivated to manage the complexities of return to work for employees returning with CMDs (Munir et al., Citation2012).

Fosse et al. (Citation2019) distinguished between two types of destructive leadership, the passive type also identified by DeRue et al. (Citation2011), and exemplified in our sample by the indifferent supervisor, and active destructive leadership. Einarsen et al. (Citation2007) described the destructive leaders as leaders who violate the legitimate interests of the organisation and engage in hostile and verbal behaviours (Tepper, Citation2000) and use their power oppressively (Ashforth, Citation1994). The demeaning supervisors in our study fit this description, they made patronising and derogatory comments and used their power to make work adjustments without the consent of returned employees. Although demeaning supervisors may not express their attitudes explicitly, actions speak louder than words when they side-lined returned employees without consultation and consent and refused returned employees career opportunities. There are also clear indications of the presence of stigma in reports of the demeaning supervisors. Link and Phelan (Citation2001) describe among other features that stigma exists where individuals distinguish and label differences between people; link these differences to negative stereotypes; and where a power difference exists between the stigmatiser and the stigmatised. Employees were treated by supervisors “as the mental illness, not the person” and described as “damaged goods” demonstrating the unacceptable stigmatisation by demeaning supervisors. This emphasises the importance of addressing mental health stigma in the workplace as one part of the RTW jigsaw.

Dominant leadership styles such as transformational leadership have been criticised for lacking a clear theoretical definition and operationalisation (Antonakis et al., Citation2016; van Knippenberg & Sitkin, Citation2013). Siangchokyoo et al. (Citation2020) suggested that transformational leadership leapt prematurely from the nascent to the mature stages of theory development. We see the present study as the nascent stage of theory development to develop a framework for supervisor attitudes and behaviours, which may influence how returned employees with CMDs experience their RTW journey.

Implications for practice

Our results provide a nuanced picture of the interventions that may be needed to optimise the supervisor support to returned employees. The indifferent supervisors were described as lacking the skills and the motivation to support returning employees. In the study by Alvesson and Sveningsson (Citation2003), leaders reported they had to develop skills to listen suggesting that indifferent supervisors can learn to become compassionate managers. Interventions appropriate for the indifferent supervisors would be creating awareness of mental health issues to increase understanding and skill development to equip them to sensitively and successfully engage in the difficult conversations about work and health, particularly with regard to the RTW interview and the ongoing provision of work adjustments. Previous research has confirmed the effectiveness of mental health awareness training (Dimoff & Kelloway, Citation2019).

The demeaning supervisors were described as not only lacking understanding but treating returned employees like pariahs and as the illness rather than a person. In the case of the demeaning supervisors, stigmatisation training and education about mental health issues may be the first step. The primary focus on these supervisors would be to change attitudes before moving on to developing their skills. In circumstances where an employee returns under the supervision of a demeaning supervisor, it could be of great benefit for them to receive additional support from others in the organisation. Without someone to turn to when they are experiencing difficulties, in the hands of a demeaning supervisor the organisation is likely to be at risk of exposing the returned employee to foreseeable harm. Clear signposting to support (for example, from another manager within the department) is of vital importance.

Interventions to optimise the compassionate supervisors’ support may not focus on changing supervisors themselves but changing the context they operate in to allow them to offer appropriate support. Our results point to the importance of flexible RTW policies that enable supervisors to make suitable work adjustments and subsequent support to readjust these as time goes on. It is also important that supervisors are allocated discretion to overrule punitive sickness absence policies to accommodate the fluctuations in mental health states of returned employees. Clear boundaries are required between senior and line management to avoid senior management interfering negatively in the support offered by supervisors. Previous research has found that supervisors who demonstrate a greater commitment to supporting employees’ return had an impact on the departments’ performance (Nielsen et al., Citation2018). Transferring this finding to our study, it suggests that supervisors should be given performance targets that incorporate support for returned employees and that returned employees should at least for a while after return not be included in departmental targets until their work functioning increases to pre-sickness levels. Finally, systems must also be in place to ensure supervisors implement and follow up on work adjustments.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of our study is the large sample size, way beyond the recommended 12–15 for thematic analysis (Clarke & Braun, Citation2014) and the comprehensive steps we took to ensure trustworthiness (for further information see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21298398.v1). Our study is not without limitations. One potential limitation is that the supervisor behaviours may be specific to the UK context. The HSE guidelines do not specify policies nor guidance for supervisors in the sustainable phase whereas in other countries such as Germany guidance is in place (https://www.baua.de/EN/Topics/Work-and-health/Workplace-health-management/Operational-integration-management/Operational-integration-management_node.html) or the Netherlands where organisations carry the economic burden of workers on sick leave for two years (https://hrmnetherlands.com/sick-leave/) and thus supervisors may be more motivated to prevent relapse. It is possible that our findings cannot easily be transferred to these settings, however, as our findings are somewhat like more universal leadership behaviours, we propose that the behaviours may be universal.

Another potential limitation of our study is that we do not triangulate data by including supervisors and other key stakeholders. We did interview supervisors but did not include them in these analyses because the main focus is on the perceptions of employees on how supervisory attitudes and behaviours of supervisors facilitated or hindered them staying and thriving at work and because the supervisors we interviewed all portrayed themselves in a positive light, either because they were unaware of their impact on followers (Lee & Carpenter, Citation2018) or because we only managed to recruit compassionate supervisors. It could be assumed that indifferent and demeaning supervisors would take no interest in participating in such as study as this. The lack of inclusion of supervisors is that we have limited insights into the barriers and facilitators to providing support supervisors may have experienced.

Conclusion

The contributions of our research study are threefold. First, we contribute to the literature on supervisors in the RTW journey, focusing on the sustainable phase. We identified three types of supervisor attitudes and behaviours; the compassionate, the indifferent, and the demeaning. Our results contribute to the scarce literature on negative supervisory attitudes and behaviours of which we found two types; the indifferent supervisors lack commitment and interest and the demeaning supervisors display stigmatising behaviour. Second, we contribute to the existing literature, which has failed to consider the stability of supervisors’ support throughout the RTW journey. We found that returned employees perceived that supervisors’ attitudes and behaviours remained stable over time, for example, compassionate supervisors were perceived as compassionate before, during and after return. Third, focusing on the sustainable RTW phase, post return, our study contributes to the field of research focused on the support that returned employees may need in the years post-return. We found that employees who have a history of sickness absence due to CMDs continued to need support years after return. Flexibility and ongoing adjustments are needed to accommodate the needs of returned employees, and that this flexibility seems most forthcoming when compassionate supervisors were afforded the decision latitude to act in the interests of their returning employees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aas, R. W., Ellingsen, K. L., Lindøe, P., & Möller, A. (2008). Leadership qualities in the return to work process: A content analysis. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 18(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9147-y

- Alvesson, M., & Sveningsson, S. (2003). Managers doing leadership: The extra-ordinarization of the mundane. Human Relations, 56(12), 1435–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035612001

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publications.

- Andersen, M. F., Nielsen, K., & Brinkmann, S. (2014). How do workers with common mental disorders experience a multidisciplinary return-to-work intervention? A qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(4), 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9498-5

- Antonakis, J., Bastardoz, N., Jacquart, P., & Shamir, B. (2016). Charisma: An ill-defined and ill-measured gift. Annual Review of Organizatioanl Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062305

- Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty tyranny in organizations. Human Relations, 47(7), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700701

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (Eds.). (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Sage.

- BITC. (2019). Mental health at work report 2019: Time to take ownership. Business in the Community.

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2014). Thematic analysis. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 6626–6628). Springer.

- Corbière, M., Mazaniello-Chézol, M., Bastien, M. F., Wathieu, E., Bouchard, R., Panaccio, A., Guay, S., & Lecomte, T. (2020). Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on sick-leave due to common mental disorders: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 30(3), 381–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09861-2

- Corbière, M., Mazaniello-Chézol, M., Lecomte, T., Guay, S., & Panaccio, A. (2021). Developing a collaborative and sustainable return to work program for employees with common mental disorders: A participatory research with public and private organizations. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1931481

- DeRue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E. D., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x

- Dimoff, J. K., & Kelloway, E. K. (2019). With a little help from my boss: The impact of workplace mental health training on leader behaviors and employee resource utilization. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000126

- Einarsen, S., Aasland, M. S., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behavior: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

- Etuknwa, A., Daniels, K., & Eib, C. (2019). Sustainable return to work: A systematic review focusing on personal and social factors. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 29(4), 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09832-7

- Fosse, T. H., Skogstad, A., Einarsen, S. V., & Martinussen, M. (2019). Active and passive forms of destructive leadership in a military context: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(5), 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1634550

- Gjerde, S., & Alvesson, M. (2020). Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Human Relations, 73(1), 124–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823243

- Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(1), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.10.006

- Hees, H. L., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Koeter, M. W., Bültmann, U., & Schene, A. H. (2012). Towards a new definition of return-to-work outcomes in common mental disorders from a multi-stakeholder perspective. PLoS One, 7(6), e39947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039947

- Johnston, V., Way, K., Long, M. H., Wyatt, M., Gibson, L., & Shaw, W. S. (2015). Supervisor competencies for supporting return to work: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 25(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9511-z

- Joosen, M. C., Lugtenberg, M., Arends, I., van Gestel, H. J., Schaapveld, B., Terluin, B., Van Weeghel, J., Van Der Klink, J. J., & Brouwers, E. P. (2021). Barriers and facilitators for return to work from the perspective of workers with common mental disorders with short, medium and long-term sickness absence: A longitudinal qualitative study. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 272–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-10004-9

- Joosen, M. W. C., Arends, I., Lugtenberg, M., Timmermans, J. A. W. M., Bruijs-Schaapveld, B. C. T. M., Terluin, B., van Weeghe, J., & Brouwers, E. P. M. (2017). Barriers to and facilitators of return to work after sick leave in workers with common mental disorders: Perspectives of workers, mental health professionals, occupational health professionals, general physicians and managers. IOSH.

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of texts. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 256–270). Sage.

- Koopmans, P. C., Bültmann, U., Roelen, C. A., Hoedeman, R., van der Klink, J. J., & Groothoff, J. W. (2011). Recurrence of sickness absence due to common mental disorders. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 84(2), 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-010-0540-4

- Ladegaard, Y., Skakon, J., Elrond, A. F., & Netterstrøm, B. (2019). How do line managers experience and handle the return to work of employees on sick leave due to work-related stress? A one-year follow-up study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(1), 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1370733

- Lee, A., & Carpenter, N. C. (2018). Seeing eye to eye: A meta-analysis of self-other agreement of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.06.002

- Lemieux, P., Durand, M. J., & Hong, Q. N. (2011). Supervisors’ perception of the factors influencing the return to work of workers with common mental disorders. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21(3), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9316-2

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Munir, F., Yarker, J., Hicks, B., & Donaldson-Feilder, E. (2012). Returning employees back to work: Developing a measure for supervisors to support return to work (SSRW). Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 22(2), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9331-3

- Negrini, A., Corbière, M., Lecomte, T., Coutu, M. F., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., St-Arnaud, L., Durand, M. J., Gragnano, A., & Berbiche, D. (2018). How can supervisors contribute to the return to work of employees who have experienced depression? Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 28(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9715-0

- Nielsen, K., & Taris, T. W. (2019). Leading well: Challenges to researching leadership in occupational health psychology – and some ways forward. Work & Stress, 33(2), 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1592263

- Nielsen, K., Yarker, J., Munir, F., & Bültmann, U. (2018). IGLOO: An integrated framework for sustainable return to work in workers with common mental disorders. Work & Stress, 32(4), 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1438536

- Noordik, E., Nieuwenhuijsen, K., Varekamp, I., van der Klink, J. J., & van Dijk, F. J. (2011). Exploring the return-to-work process for workers partially returned to work and partially on long-term sick leave due to common mental disorders: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 33(17–18), 1625–1635. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.541547

- Norder, G., Bültmann, U., Hoedeman, R., Bruin, J. D., van der Klink, J. J., & Roelen, C. A. (2015). Recovery and recurrence of mental sickness absence among production and office workers in the industrial sector. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(3), 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku202

- Norder, G., van der Ben, C. A., Roelen, C. A., Heymans, M. W., van der Klink, J. J., & Bültmann, U. (2017). Beyond return to work from sickness absence due to mental disorders: 5-year longitudinal study of employment status among production workers. European Journal of Public Health, 27(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw178

- OECD. (2014). Making mental health count: The social and economic costs of neglecting mental health care. OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing.

- Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- Parsonage, M., & Saini, G. (2017). Mental health at work. Center for Mental Health.

- Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

- Siangchokyoo, N., Klinger, R. L., & Campion, E. D. (2020). Follower transformation as the linchpin of transformational leadership theory: A systematic review and future research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(1), Article 101341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101341

- Ståhl, C., & Stiwne, E. E. (2014). Narratives of sick leave, return to work and job mobility for people with common mental disorders in Sweden. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24(3), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-013-9480-7

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

- Thomas, R., & Linstead, A. (2002). Losing the plot? Middle managers and identity. Organization, 9(1), 71–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840291004

- Tjulin, Å, MacEachen, E., & Ekberg, K. (2010). Exploring workplace actors’ experiences of the social organization of return-to-work. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 20(3), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9209-9

- van Knippenberg, D., & Sitkin, S. B. (2013). A critical assessment of charismatic-transformational leadership research: Back to the drawing board? The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 1–60. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.759433