Abstract

Background

After a mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI,) a significant number of patients may experience persistent symptoms and disabilities for months to years. Early identification and timely management of persistent symptoms may help to reduce the long-term impacts of mild TBIs. There is currently no formalised method for identifying patients with persistent symptoms after mild TBI once they are discharged from emergency department.

Objective

Assess the feasibility of a remote monitoring tool for early identification of persistent symptoms after mild TBI in the outpatient setting using digital tools.

Methods

Electronic surveys were sent to patients with mild TBI who presented to the emergency department at a Major Trauma Centre in England. The surveys were completed at three different timepoints (within days of injury (S1), 1 month (S2), and 3 months (S3) after injury). The indicators used to assess feasibility were engagement, number of eligible patients for follow-up evidence of need for the intervention, and consistency with the literature. Feedback was sought from participants.

Results

Of the 200 people invited to participate, 134 (67.0%) completed S1, 115 (57.5%) completed S2, and 95 (47.5%) completed S3. The rates of persistent symptoms ranged from 17.9%–62.6% depending on the criteria used, and we found a significant proportion of the participants experienced morbidity 1 and 3 months after injury. The electronic follow-up tool was deemed an acceptable and user-friendly method for service delivery by participants.

Conclusion

Using digital tools to monitor and screen mild TBI patients for persistent symptoms is feasible. This could be a scalable, cost-effective, and convenient solution which could improve access to healthcare and reduce healthcare inequalities. This could enable early identification of patients with further medical needs and facilitate timely intervention to improve the clinical workflows, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes for people with persistent morbidities after mild TBIs.

Introduction

According to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, more than a million people present to Emergency Departments (ED) in England and Wales with a head injury and approximately 90% of these are mild.Citation1 These are caused by an external force to the head, most commonly in road traffic accidents, falls, and sports, leading to a cascade of ionic, metabolic, and physiological events that disturb cerebral function.Citation2 Patients may experience acute clinical events such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, vomiting, and a range of symptoms after injury.

Recovery after a mild traumatic brain injury (mild TBI; also known as concussion) varies between individuals with no established method to predict the patient’s trajectory. While most patients who sustain a mild TBI recover spontaneously within days to a couple of weeks, a significant number of patients experience symptoms for months to years after injury.Citation3 This impacts the patient’s daily functioning and, in turn, their relationships, ability to return to work, finances, quality of life, and life satisfaction.Citation4 These patients require further medical attention beyond the initial review during the acute phase to recover appropriately. However, there is no formalised method for monitoring and screening patients with mild TBI in order to identify those with persistent difficulties and provide them with the appropriate care they need to recover.

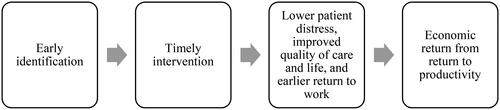

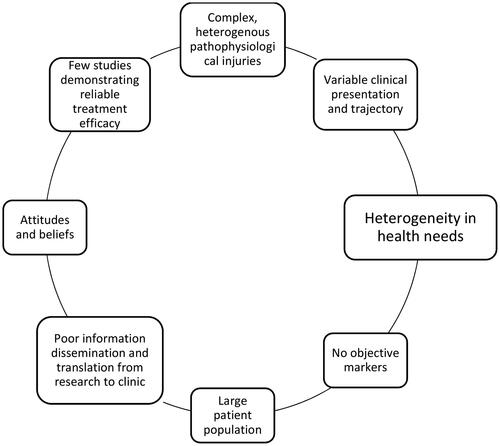

In such a heterogenous patient population, healthcare needs differ between patients and care must be tailored to meet their individual needs. Current clinical practice often assumes patients with a mild TBI will recover with little or no intervention thus neglecting patients with prolonged recovery. Early identification and timely management of persistent symptoms may help to limit the damaging effects these injuries can have on patients’ lives (). However, without structured follow-up, timely intervention is challenging and, in turn, prolong may, or in some cases potentially prevent, patient recovery. The absence of a pathway to follow-up services can be attributed to a multitude of challenges that have historically plagued the mild TBI field, including a lack of evidence on effective therapeutic approaches (). However, growing research in recent years has provided evidence for management strategies that could improve recovery and patient outcomes.Citation5–13 Clinical services need to expand in order to identify patients needing follow-up and deliver best-practice management in outpatient clinics without overburdening healthcare services and wasting resources on patients who recover spontaneously. Thus, a cost-effective monitoring and screening solution is needed to accomplish this.

Digital health interventions (DHIs) provide a solution for overcoming many challenges in healthcare, including a cost-effective and scalable solution for remote monitoring and screening.Citation14,Citation15 According to the Department of Health and Social Care, the adoption of digital technologies is a priority for the NHS.Citation16 The use and acceptability of these technologies in healthcare has accelerated since the COVID-19 pandemic, and the NHS is seeking to ensure the transition continues into long-term and sustainable changes.Citation17 Among its many benefits, DHIs are convenient, widen access, scalable, cost-effective, and provide patients with more autonomy in their own care.Citation18 In a recent policy paper, the plan for the transformation to a digitally-enabled healthcare system was outlined to achieve personalised healthcare, reduce healthcare disparities, improve hospital performance and efficiency, and improve patient experience, satisfaction, and outcomes.Citation19

DHI tools are particularly beneficial for the mild TBI population given the large population size and heterogenous nature of these injuries. Using DHI tools, the population could be monitored and screened remotely to identify individuals with persistent difficulties and create a digitally-enabled pathway from ED to outpatient clinics by providing an efficient, cost-effective solution for an automated mass screening system which could direct and refer patients towards the appropriate clinical pathway. Therefore we performed a local feasibility study to evaluate implementation an electronic follow-up survey to screen and identify mild TBI patients with persistent symptoms to triage to outpatient clinic.

Methods

This was a feasibility study assessing the feasibility of using a DHI tool for follow-up after mild TBI in the UK. This feasibility study was performed at a Major Trauma Centre between March 2022 and September 2022. The study was approved by the local governance team at Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) NHS Foundation Trust. As this study was part of a service evaluation, no further ethical approvals were required.

Participants

All patients aged 16 and above presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) at CUH and discharged directly from the ED with a GCS 15 were screened for eligibility by a member of the outpatient neurotrauma team. Patients were eligible if they had sustained a head injury with one or more of the following (1) met criteria for a CT scan according to NICE guidance, (2) loss of consciousness for <30 min, (3) post-traumatic amnesia for <24 hours, or (4) experienced at least one of the following symptoms in ED: headache, dizziness, vomiting, or vision disturbance.Citation20 Patients were excluded if they (1) did not speak English, (2) had known cognitive deficits, (3) had surgical management of a cranial injury, (4) had no access to email, or (5) did not have capacity to consent. We aimed to include 200 participants as this was determined to be an adequate number to evaluate study feasibility. While feasibility studies typically have a lower number of participants, a higher number was required for this study given that only a proportion of mild TBI patients experience persistent symptoms.

Study design

Patients meeting the inclusion criteria above were contacted by email within 3 days of being discharged from ED. Online surveys were sent to patients at three timepoints; Survey 1 (S1) was sent within days after ED discharge as the first point of digital contact, Survey 2 was sent 1 month after injury, and Survey 3 (S3) was sent 3 months after injury (). S2 and S3 were sent 1 and 3 months after injury, respectively, regardless of when the patient presented to ED as not all patients present to ED on the day of injury. Following the initial survey invitation, up to five reminder emails were sent to participants who had not completed the survey. All patients consent by agreeing to participate on the introductory page where consenting was required before proceeding to the survey page. A feedback survey was sent to participants who completed the final survey (S3).

Demographics and injury-related events were collected from clinical notes in electronic medical records, including date and cause of injury, date of presentation to ED, evidence of PTA or loss of consciousness, and eligibility for CT head. Of note, CT head results were not evaluated against outcome as that was determined to be outside the scope of this feasibility study.

The feasibility study was designed to make the study process similar to a potential future clinical process for the patients. The results in this feasibility study did not influence patient care and clinical practice.

Survey composition

The surveys were web-based using a secure GDPR compliant software (Online Surveys, https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk) provided by the Cambridge University Hospital NHS Trust. The surveys sent via email with individualised links for each participant generated by the survey software.

All three surveys included the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptom Questionnaire (RPQ),Citation21 a global rating of change (GRC) scale,Citation22 a global perceived effect (GPE) scaleCitation23 and a return-to-work question (). Additionally, S1 contained demographics questions, including history of previous head injuries, psychological difficulties, or neurological difficulties. S2 and S3 included a healthcare utility question. S3 also included the EQ-5D-5L and feedback questions on the acceptability and usability of the service. Please see supplementary material for further details. All items and questionnaires were included due to their validity and reliability or their recognised utility in the mild TBI population.

Table 1. Survey composition.

The RPQ is a validated 16-item self-reported symptom scale for measuring symptoms after a mild TBI.Citation21 The questionnaire contains the most reported symptoms where the patients are asked to rate the presence and severity of individual symptoms over the last 24 hours compared to before injury. Patients can also add and rate two additional symptoms they may be experiencing that are not included in the questionnaire. This is to ensure that less common symptoms are also captured by the questionnaire. All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not experienced at all) to 4 (severe). Of note, 1 represents symptoms that the patient previously experienced but are no longer a problem, 2 represents a mild problem, 3 represents a moderate problem, and 4 represents a severe problem. Thus, higher values indicate greater symptom severity.

The GRC and GPE are both single-item patient-reported scales and are used in clinical research due to their ease of use and efficiency.Citation22,Citation23 The GRC measures the patients perceived change in health using a seven-point Likert scale indicating the degree and direction of change. The GPE measures the patient’s perception of the degree to which their injury effects their life on a seven-point Likert scale. Both scales add value to the survey by measuring the patient’s perception of their injury and can guide healthcare professional’s approach during consultations.

The EQ-5D-5L is a valid and reliable questionnaire widely used for measuring health-related quality of life.Citation24 As the name suggests, it assesses five dimensions through five items each with 5-point Likert scales. The ED-5D-5L was chosen due to it pragmatic length and its use for health economic analyses.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for this feasibility study were related to the feasibility of an eFollow-up service determined using feasibility indicators.Citation25

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Evaluation defines a feasibility study as ‘pieces of research done before a main study in order to answer the question ‘Can this study be done?’…. [and are] used to estimate important parameters that are needed to design the main study’.Citation26 This includes number of eligible patients, follow-up rates, response rates on questionnaires, and adherence/compliance rates.Citation27 The purpose of feasibility studies is not to evaluate the outcome of interest (utility of a DHI tool for monitoring and screening symptoms after a mild TBI) as this is the purpose of the main study.

Evaluation of feasibility in this study was based on methods described in the literature ().Citation25

Table 2. Indicators used for assessment of feasibility.

Engagement was assessed through completion rates for each survey. The number of eligible patients for follow-up and evidence of need for the intervention were both primarily assessed by calculating the number of patients meeting the criteria for persistent symptoms. There is no consensus on the definition of persistent symptoms after mild TBI and so we used common existing definitions in the literature.Citation28 The frequencies for symptom burden were calculated with four different operational definitions for persistent symptoms after mild TBI. The four definitions were; (a) endorsing 1 or more symptoms of any severity (rated 2 or greater of RPQ), (b) endorsing 3 or more symptoms of any severity (rated 2 or greater of RPQ), (c) endorsing 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms (rated 3 or greater of RPQ), and (d) endorsing 3 or more moderate-severe symptoms (rated 3 or greater of RPQ). The symptom burden frequencies for all four definitions were calculated for 1 month and 3 months after injury.

Feedback was collected through a separate feedback survey sent to participants who had completed S3 and agreed be contacted for further feedback.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using RStudio 2022.07.2. Descriptive statistics were used to report demographic characteristics, symptom rates, return to work rates, and feedback.

Results

Two hundred patients presenting to the local ED were invited to participate in the clinical process. Demographics information is given in . The most common causes of injury were falls (37%), road traffic accidents (20.5%), and sports (15.5%). 41.5% had a CT scan of which 6 people had positive CT findings.

Table 3. Demographics.

Engagement

Of the 200 people invited to participate, 134 (67.0%) completed S1, 115 (57.5%) completed S2, and 95 (47.5%) completed S3.

Number of eligible patients for follow-up

Of the people who completed S2, 62.6% endorsed 1 or more symptoms and 49.6% endorsed 3 or more symptoms at any severity. 37.4% endorsed 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms and 20.9% endorsed 3 or more moderate-severe symptoms. Of the people who completed S3, 55.8% endorsed 1 or more symptoms and 43.2% endorsed 3 or more symptoms at any severity. 29.5% endorsed 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms and 17.9% endorsed 3 or more moderate-severe symptoms. Thus, the proportion of eligible people for follow-up based on symptom burden in our cohort ranges from 17.9%–62.6% depending on the criteria used ().

Table 4. Number of eligible patients for follow-up.

76.9% patients who had 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms at S1 completed S2 and 79.1% of patients who had 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms at S2 completed S3

Evidence of need for the intervention and consistency with literature

Of the 115 participants who completed S2, at least 20.8% endorsed moderate-severe symptoms (). 42.6% reported they felt their head injury affected their life ranging from ‘a little’ to ‘an extremely large amount’ and 11.3% reported they feel their health has ‘not changed’ or is ‘worse/much worse’ 1 month after injury. Within 1 month, 27.8% had sought follow-up of some form; in their GP surgery (n = 21, 18.3%), returned to ED (n = 6, 5.2%), or ‘other specialists’ (n = 6, 5.2%), including maxillofacial, osteopathy, neurosurgeon, and cardiologist. 20.9% had not returned to work and 7.8% had returned to work but not to their pre-injury capacity within 1 month of injury.

Table 5. Evidence of need for the intervention. Symptom burden in this cohort which may indicate a potential need for follow-up.

The rate of moderate-severe symptom endorsement at 3 months was 17.9% for the 95 participants who completed S3. 29.5% reported they felt their head injury still affected their lives ranging from ‘a little’ to ‘an extremely large amount’ and 15.8% reported they felt their health has ‘not changed’ or is ‘worse/much worse’ 3 months after injury. 24.2% of respondents reported they had sought follow-up from their GP (n = 13, 13.7%), returned to ED (n = 5, 5.3%), or ‘other specialists’ (n = 6, 6.3%). ‘Other specialists’ included neurologists, neurosurgeons, ENT, memory clinic, and college nurse. By 3 months, 18.9% had not returned to work and 4.2% had returned to work but not to their pre-injury capacity.

Feedback

The delivery method was found to be acceptable by 99% of participants, 99% found it to be user-friendly, and 98% were happy with the electronic format of the survey. No participant said they did not find the process acceptable.

The feedback survey sent separately after S3 had 50 responses (supplementary material). 54% of these respondents reported having recovered within 4 weeks of injury and 26% reported having experienced symptoms or other head injury effects for longer than 12 weeks. Most participants reported they were satisfied with the care they received and it had met their health needs related to the head injury (‘Strongly agree’/‘Agree’=78%, ‘Strongly agree’/‘Agree’=71%), while 10% and 12% disagreed and neither agreed or disagreed with the statements, respectively. When asked about follow-up, 56% felt head injury-related services were accessible to them, about a quarter neither agreed or disagreed and 16% did not feel such services were accessible. Similarly, about half of the participants said they would know how to access follow-up if needed, while 33% reported they would not know who to contact or where to go for follow-up. In addition, 60% of participants felt they personally would have benefitted from follow-up after their head injury. When asked about whether everyone who has had a mild TBI/head injury should be offered follow-up, 80% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement and 4% disagreed. Regarding digital services, 80% reported they would use an electronic follow-up questionnaire for monitoring after a head injury. 88% said they would use an electronic questionnaire service after a head injury if they were experiencing persistent symptoms and 71% said they would use such a service if they had fully recovered after their head injury. Email was reported as the preferred delivery format for electronic follow-up services (reported by 74%) compared with phone call (25%), SMS (20%), and mobile app (14%).

Discussion

Applying DHI in mild TBI may help to improve care and broaden services beyond traditional methods to meet the variety of healthcare needs in the patient population which has significant unmet needs. These tools could help create a patient pathway from acute settings to follow-up in specialist outpatient clinics in a convenient, scalable and cost-effective manner. In this study, we demonstrated that an electronic follow-up service is feasible to set-up and can help identify patients with persistent symptoms with little resources needed for the service.

Engagement

Engagement with the service was satisfactory, but as expected, response rates dropped with each survey round. This could be improved by providing sufficient information at discharge about the service and adjusting expectations about recovery. While most will recovery spontaneously within a month, improving awareness about the risks of prolonged recovery could help all patients be mindful about their health after injury and prevent causing distress to patients who ‘unexpectedly’ suffer head injury-related problems for longer than the expected timeline. Additionally, providing follow-up with a healthcare professional, either via telemedicine or in-person, after survey completion would encourage completing the surveys as patients will see the direct benefits of engaging with the service. However, evaluating the feasibility of using DHIs in mild TBI care is essential prior to changing clinical practice. This needs to be assessed in the next phase of the study.

While it is preferred for most, if not all, patients to complete the eFollow-up surveys, the purpose of such a service is to ensure all patients are offered follow-up following a mild TBI. Most people will recover without further medical review but there is currently no robust way to predict recovery trajectories and so follow-up services would need to be offered to all patients presenting with a mild TBI to capture patients with persisting problems. Thus, given the high number of patients, it is even more critical to have a scalable, cost-effective solution for this population, such as DHIs. Nonetheless, we hypothesise that while some patients may not complete the surveys, the patients experiencing prolonged recovery and needing follow-up would utilise the service.

Number of eligible patients for follow-up

As there is no consensus on the definition of prolonged recovery or persistent symptoms following a mild TBI, this needs to be defined prior to doing a larger trial of this study. Here we used a variety of definitions used in the literature to estimate the proportion of patients requiring follow-up from a healthcare professional and it ranged from 17.9%–62.6%.Citation29,Citation30 This depends on the timeline, the severity of a symptom, and the type and number of symptoms the patient is experiencing after injury. Additional factors to consider would be whether the symptom would have to be new after injury or whether exacerbation of pre-injury symptoms would also be considered.

The broadest criteria (1 or more symptoms at any severity) showed that 63% of patients would qualify for follow-up a month after injury and 56% would qualify 3 months after injury. Adjusting for response rates (assuming all people who did not complete the surveys fully recovered, this would be 36.0% (72/200) and 26.5% (53/200) 1 and 3 months after injury, respectively. On the other hand, the strictest criteria (3 or more moderate-severe symptoms) showed 20.9% and 18.9% would qualify for follow-up 1 and 3 months after injury, respectively. Again, adjusting for response rates, this would be 12.0% and 9.0% at 1 and 3 months after injury, respectively. Regardless, these numbers demonstrate that a significant number of patients require follow-up only based on symptom-burden and services must be designed accordingly with the resources to accommodate these patient numbers.

When determining the criteria for follow-up in future studies, it may be symptom-based, such as what we have assessed here, or it may be more appropriate to assess based on return-to-work, functional levels, patient-reported health status, or other relevant factors. Given there are no objective measures for prolonged recovery, this needs to be determined based on the available literature, expert-opinion, patient and carer input, and clinical feasibility.

We have no data on the patients who were lost to follow-up, however 76.9% patients who had 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms at S1 completed S2 and 79.1% of patients who had 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms at S2 completed S3. This suggests that symptomatic patients are more likely to complete the survey while those who have recovered are not motivated to continue with the surveys. From a utilitarian perspective, designed to capture those patients with ongoing problems requiring dedicated specialist follow-up, loss to follow-up of patients who have recovered is less problematic.

Evidence of need for the intervention and consistency with literature

In addition to the above, other measures could be evaluated that demonstrate the need for a follow-up service in the mild TBI population. Based on self-reporting of health status, a significant number of patients reported feeling mild TBI related symptom burdens 3 months after injury. These levels were similar to experiencing 1 or more moderate-severe symptoms both at 1 month and 3 months after injury.

A month after injury, 20.9%, or 12.0% when adjusting for response rates assuming all non-responders fully recovered, had not returned to work and this number was still high 3 months after injury at 18.9%, or 9.0% adjusted for response rates. This has a financial toll on patients and their families and the productivity loss has implications for society, which are more evident when considering that more than 1million people in the UK present to EDs with a head injury every year of which 90% are mild.Citation31 Additionally, the potential costs associated with inefficient healthcare utility add to the economic costs of mild TBIs. While assessing the patient pathway was beyond the scope of this study, the survey contained a question about whether the patient sought out follow-up after being discharged from an ED. The results showed more than a tenth of patients had (when adjusting for response rates) and there was no consistency in the clinic or specialties involved. Instead, patients seemed to have sought out follow-up clinicians or other healthcare professionals based on availability and access.

The degree of injury burden was consistent with the literature and thus demonstrating these results are representative for the wider mild TBI population.Citation30,Citation32,Citation33

Feedback

According to the WHO guidelines, development of DHIs should be focussed on the user experience.Citation34 Therefore, evaluating the acceptability and usability of the tool and a digital follow-up service are an important measure of feasibility. Overall, the eFollow-up service was very well received and deemed acceptable and user-friendly by participants.

Most participants were satisfied with the care they received, but at least 10% were dissatisfied and felt it had not met their head injury-related health needs. Future follow-up services after mild TBI should primarily be aimed at this minority group which still make up a significant number of people. Furthermore, while more than half felt head injury-related services were accessible to them, about a third of responders said they did not know how to seek out further care. These results are expected and consistent with the current service structure. There is no patient pathway following the initial acute phase, leaving the burden of seeking out further care on the patient. This often means patients are not presenting to suitable clinical services which results in wasteful practices and delays care. Standardising the patient pathway with structured follow-up available to patients who need it, and providing sufficient information and awareness, would provide a more efficient and effective healthcare system with improved health outcomes, patient satisfaction, and reduced costs. The vast majority felt everyone who has experienced a mild TBI should be offered follow-up. Interestingly, 60% reported they felt their health needs had been met, yet 71% said they personally felt they would have benefitted from follow-up. These results suggest the need for follow-up services is felt by patients regardless of health status.

Most said they would use an electronic follow-up service, regardless of whether they had fully recovered or experiencing symptoms, with email being the preferred method of delivery. While this could have been biased by the responders have had received the service through email, this delivery method is a convenient and accessible format suitable for a trauma-based patient population.

Future direction

The next stage of this work is to develop a clinically validated eFollow-up tool to implement into clinical practice. To ensure benefits in health outcomes, costs, and efficiency, as well as clinical uptake, the study design needs to ensure all factors are considered using a mixed-methods approach. This includes developing and designing the service structure and the eFollow-up tool that is clinically valid and appropriately evaluates recovery, assess the facilitators and barriers for the clinical workflow, and evaluate the efficacy, costs, and benefits to all stakeholders in a local trial prior to national implementation. Additionally, clinical practice in outpatient clinics should be restructured to provide standardised best-practice healthcare in order to improve quality of care and health outcomes after a mild TBI. The eFollow-up tool provides a solution to facilitate the delivery of best-practice management in these clinics.

Limitations

Access to email and digital literacy may be limitations of the service format. However, in terms of email access, only one patient approached for our feasibility study did not have an email address. We anticipate these factors to be less of an issue with time, particularly in the post-pandemic era where DHIs are increasingly adopted into clinical practice.

The study was limited to the English-speaking population. While this was deemed appropriate for the feasibility study due to its scale and scope, future studies should include and facilitate for the non-English speaking population as well. This can be aided with translation tools for accurate and reliable results. This is critical for validation of the digital survey and service, and to ensure inclusion and equitable accessibility across the wider UK population.

While the surveys were composed of existing validated questionnaires, all widely used in clinical research, the full survey itself was not validated for assessing recovery after mild TBI. However, developing a validated method for assessing recovery was beyond the scope of this study. This is a critical step prior to implementation of such a service and must be addressed in future work.

The results from the feedback survey may be influenced by the sub-population completing these sections experiencing higher disease burdens than the overall population. A quarter of the patients experienced symptoms and head injury-related effects for longer than 12 weeks. However, we believe this to not have made a significant difference to the results and the message of the study.

Lastly, the feasibility and validity of a DHI is typically assessed through comparison against the gold-standard. However, there is no gold-standard assessment of recovery after a mild TBI, and so evaluating the validity of the DHI was not possible in this study and should be carefully considered in future work.

Conclusions

There is no structured follow-up after suffering a mild TBI in England despite there being a significant number of patients needing further care after the acute phase. DHIs provide a scalable, cost-effective, and convenient solution for remote monitoring and screening health needs which could improve access to healthcare and reduce healthcare inequalities. We have trailed a simple solution using an eFollow-up tool has a satisfactory level of engagement with potential for further improvements with modest changes, there is a need and demand for a service to enable follow-up, and the eFollow-up tool is feasible to implement and deemed an acceptable method for service delivery by mild TBI patients. Future work should evaluate the wider implications of developing and implementing such a service into clinical practice, and demonstrate the benefits to patients, providers, and healthcare systems.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (226.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the people who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- NICE guideline. 2023. Head injury: assessment and early management.

- Giza CC, Hovda DA. The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion. Neurosurgery 2014;75 Suppl 4:S24–S33.

- Varner C, Thompson C, de Wit K, Borgundvaag B, Houston R, McLeod S. Predictors of persistent concussion symptoms in adults with acute mild traumatic brain injury presenting to the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med 2021;23:365–73.

- Voormolen DC, Polinder S, von Steinbuechel N, Vos PE, Cnossen MC, Haagsma JA. The association between post-concussion symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Injury 2019;50:1068–74.

- Gravel J, D'Angelo A, Carrière B, et al. Interventions provided in the acute phase for mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Syst Rev 2013;2:63.,

- Heslot C, Azouvi P, Perdrieau V, Granger A, Lefèvre-Dognin C, Cogné M. A systematic review of treatments of post-concussion symptoms. J Clin Med 2022;11:6224.

- Kane AW, Diaz DS, Moore C. Physical therapy management of adults with mild traumatic brain injury. Semin Speech Lang 2019;40:36–47.

- Kinne BL, Bott JL, Cron NM, Iaquaniello RL. Effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation on concussion-induced vertigo: a systematic review. Phys Ther Rev 2018;23:338–47.

- Nagib S, Linens SW. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy improves perceived disability associated with dizziness postconcussion. J Sport Rehabil n.d;28:764–8.

- Nygren-de Boussard C, Holm LW, Cancelliere C, et al. Nonsurgical interventions after mild traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil n.d;95:S257–S64.

- Park K, Ksiazek T, Olson B. Effectiveness of vestibular rehabilitation therapy for treatment of concussed adolescents with persistent symptoms of dizziness and imbalance. J Sport Rehabil 2018;27:485–90.

- Quatman-Yates CC, Hunter-Giordano A, Shimamura KK, et al. Physical therapy evaluation and treatment after concussion/mild traumatic brain injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2020;50:CPG1–CPG73.,

- Schneider KJ, Leddy JJ, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Rest and treatment/rehabilitation following sport-related concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:930–4.

- McKinsey and Company. 2022. Digital health: An opportunity to advance health equity.

- Rushton, S., JC, B., AA, L., AM, G., JP, S., E, V.V., JD, W., AA, T., Adam, S., Fulton, J., AS, K., MG, V.N., JW, W., KM, G., and JM, G., 2019. Effectiveness of remote triage: A systematic review. VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports.

- Department of Health and Social Care. 2018. The future of healthcare: our vision for digital, data and technology in health and care.

- Sheikh A, Anderson M, Albala S, et al. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit Health 2021;3:e383–e396.

- National Institute for Health and Care Research, 2022. What is digital health technology and what can it do for me?. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/collection/what-is-digital-health-technology/

- Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England. 2022. A plan for digital health and social care.

- Ruff RM, Iverson GL, Barth JT, Bush SS, Broshek DK, NAN Policy and Planning Committee. Recommendations for diagnosing a mild traumatic brain injury: a national academy of neuropsychology education paper. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2009;24:3–10.

- King NS, Crawford S, Wenden FJ, Moss NEG, Wade DT. The Rivermead Post Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire: a measure of symptoms commonly experienced after head injury and its reliability. J Neurol 1995;242:587–92.

- Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther 2009;17:163–70.

- Kamper SJ, Ostelo RWJG, Knol DL, Maher CG, de Vet HCW, Hancock MJ. Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:760–6.e1.

- EuroQol Research Foundation. 2019. EQ-5D-5L User Guide.

- Orsmond GI, Cohn ES. The distinctive features of a feasibility study. OTJR (Thorofare N J) 2015;35:169–77.

- Tickle-Degnen L. Nuts and Bolts of Conducting Feasibility Studies. Am J Occup Ther 2013;67:171–6.

- Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, Lancaster GA. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:67.

- Iverson GL, Karr JE, Maxwell B, Zafonte R, Berkner PD, Cook NE. Examining criteria for defining persistent post-concussion symptoms in children and adolescents. Front Neurol 2021;12:614648.

- Polinder S, Cnossen MC, Real RGL, et al. A multidimensional approach to post-concussion symptoms in mild traumatic brain injury. Front Neurol 2018;9:1113.

- Voormolen DC, Cnossen MC, Polinder S, von Steinbuechel N, Vos PE, Haagsma JA. Divergent classification methods of post-concussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury: prevalence rates, risk factors, and functional outcome. J Neurotrauma 2018;35:1233–41.

- Bloom BM, Newcombe V, Roberts I. What’s in a number? Problems with counting traumatic brain injuries. Emerg Med J 2022;39:233–4.

- Fordal L, Stenberg J, Iverson GL, et al. Trajectories of persistent postconcussion symptoms and factors associated with symptom reporting after mild traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;103:313–22.

- Losoi H, Silverberg ND, Wäljas M, et al. Recovery from Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Previously Healthy Adults. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:766–76.,

- WHO Team. 2019. Recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening.