ABSTRACT

Objective

In Australia, over 6,000 adults younger than 65 have been inappropriately placed in nursing homes designed to accommodate older adults. The primary aim of this review was to map the literature on the experiences and outcomes of young people with disability who are placed in aged care.

Methods

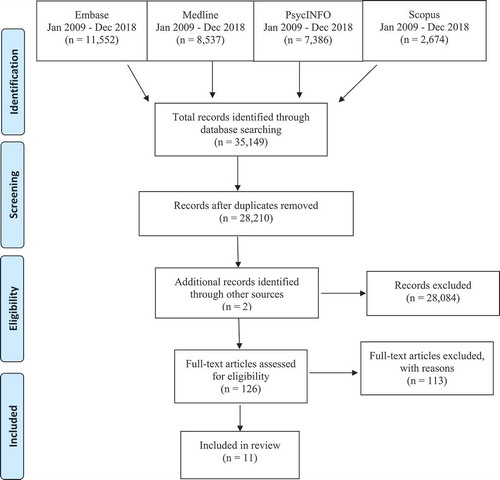

A scoping review of the published literature from 2009–2018 was conducted using Embase, Medline, PsycINFO and Scopus.

Results

Eleven articles were identified (7 qualitative, 3 mixed methods, 1 quantitative). Results demonstrated the inability of aged care facilities to meet the basic human needs of young people (e.g., privacy, physical, sexual, social, nutritional, emotional need) and highlighted the lack of choice young people with disability have in regards to rehabilitation and housing. There was limited data relating to the trajectory and support needs of young people placed in aged care facilities.

Conclusions

This review highlights the negative outcomes young people experience while living in aged care. Future research should investigate the trajectory and support needs of young people in aged care facilities. Systemic changes are required to meet the needs of young people with complex needs at risk of admission to aged care including timely rehabilitation and housing and support options.

Locating appropriate community housing for young adults with disabilities (such as acquired neurological disorders, developmental, intellectual, physical or sensory) is currently an international challenge for the disability, health and aged care sectors. Young adults with long-term high support needs have limited viable housing options following serious injury or illness (Citation1–Citation3). Sadly, residential aged care designed for older adults is the first and final option for many young adults with disability. In Australia, there are over 6,000 adults younger than 65 who have been inappropriately placed in nursing homes designed to accommodate older adults (Citation4). In the USA, it is estimated that over 200,000 young people are placed in nursing homes (Citation5), while in the UK, one in five people with spinal cord injury are discharged to a residential aged care facility (Citation3). This situation is increasingly unacceptable given the growing evidence highlighting the negative impact of being placed in aged care on the health and wellbeing of younger people (Citation6,Citation7).

There is international consensus that health is affected by where people live (or are cared for) (Citation8,Citation9). Previous research has demonstrated the effects of housing circumstances on physical and mental health for people with various complex disabilities, including acquired brain injury (Citation10,Citation11), intellectual disability (Citation12), mental illness (Citation13 Citation13 Citation14–Citation15), and individuals with other health conditions requiring 24-hour care support (Citation16,Citation17). Considering the significant amount of research demonstrating the reciprocal relationship between place and people, it is not surprising that living in aged care has been found to have a negative impact on the health and wellbeing of younger people (Citation6,Citation7,Citation18). Younger residents have substantially different needs from elderly residents and aged care facilities do not have the resources, expertise or culture to support younger people (Citation19,Citation20). For young people with disability, being placed in an ill-equipped environment often means a number of their basic human needs go unmet (e.g., social interaction, community participation, autonomy and privacy) and they can also be at risk of physical, mental and social harm (Citation2,Citation6,Citation21 Citation23–Citation25). Furthermore, most young people living in aged care are provided with little or no choice in regard to their living arrangements and are required to navigate multiple complex systems in order to move to more suitable accommodation (Citation1). Young people who are placed in aged care inappropriately, and without choice, are thus vulnerable to a variety of detrimental physical and mental health outcomes.

Allowing people with disability choice in regards to their living arrangements is a human rights issue. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (Citation18) clearly states the right for people with disability to choose where and with whom they live, and not be obliged to any particular living arrangement. The obligation to the UNCRPD has been reflected in the recent implementation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) by the Australian Government, which intends to provide more appropriate housing opportunities and support options for young people who are at risk of, or currently, living in aged care (Citation26). While the NDIS has the potential to provide the resources to solve the issue of young people in aged care in Australia, it is not a silver bullet. Despite introduction of the NDIS and international obligations to human rights, over 665 people under 55 were admitted to aged care in 2017–18 in Australia (Citation4). The recent Younger People in Residential Aged Care Action Plan recognizes that complex strategy beyond what currently exists is required to ensure that this marginalized cohort gain access to the NDIS, quality disability support and primary health services and housing (Citation27). The Action Plan is a commitment from the Australian Government to take concrete action to reduce the number of younger people aged under 65 years entering and living in aged care, and acknowledges that in order to develop viable solutions, a greater understanding of the young people who live in aged care is required.

Despite international consensus that young people with disability residing in aged care is inappropriate, there is currently an absence of a systematic account of experiences and outcomes of young people living in aged care facilities. Consequently, there is no clear evidence base to guide essential reforms. It is therefore important to review the evidence available to build a clear picture of lived experience to inform the development of effective and sensitive policy initiatives. The objective of this review was to consolidate the literature of the past 10 years, in order to: (i) understand the experience of younger people with disability when they are in aged care; (ii) understand the outcomes of younger people living in aged care; and (iii) identify any potential solutions and systemic changes that exist, or are in development, that address the issue of young people living in aged care. The current review focussed on the population of young people with disability (18–65 years) who were either currently living, or had previously lived in, an aged care facility, and their caregivers. While acquired brain injury is often the most common disability type of younger people in aged care, other disability types include degenerative neurological conditions, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability and spinal cord injury (Citation1–Citation3,Citation7,Citation19,Citation22,Citation24). Additionally, some younger people in aged care have more than one disability type (Citation19). Despite the diverse functional impairments of these cohorts, the placement of young people in residential aged care remains an issue due to the substantially different needs from elderly residents (Citation19,Citation20). The current review therefore included people with range of disabilities in order to comprehensively capture the experiences and outcomes of young people living in aged care facilities.

Method

The scoping review protocol outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation28) was followed for this review. A scoping review method was considered most appropriate as it is particularly useful in bringing together literature in disciplines where there is limited or emerging evidence. The research question that guided the review was “what are the experiences and outcomes of young people (18–65 years) with a disability who have been placed in residential aged care?” Two broad concepts informed the development of the key words that were used in the final search. The first concept described the population (i.e., persons with any form or level of physical, sensory, intellectual or developmental disability; persons with complex needs including acquired neurological disorders; and any form of mental health problem, disorder or illness), while the second concept reflected the setting of interest (i.e., care facilities designed for the elderly that are residential properties).

A search strategy based on these concepts was developed and adapted for each database with consultation from a research librarian (see Appendix for detailed search strategy). As the current review aimed to capture the literature over the past 10 years, a date limitation of 2009– 2018 was applied to searches. Although only articles written in English were included in the review, no language restrictions were applied to the searches. The databases searched were Embase, Medline, PsycINFO and Scopus. Forwards citation searches, citation searches of authors and hand searching of all papers retained for full text were conducted to identify any relevant papers not captured in the initial search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed with the aim to only include studies that would add to the understanding of the issues experienced by, and the outcomes of, young people with disability who are inappropriately placed in aged care facilities. To be included in the current literature review, studies needed to meet the following eligibility criteria. First, studies had to include a sample of young adults (i.e., aged 18–65 years) with complex needs, including with an acquired neurological disorder. Second, as some studies included participants from a range of living environments, it was required that 30% or more of participants included in the study sample had to either be currently living, or had previously lived, in an aged care facility (i.e., studies were excluded if less than 3 in 10 participants in their sample were not living in, or had not previously lived in, an aged care facility). Studies were excluded from the review if the primary focus was on individuals with an existing health condition who did not have a disability, or if the focus of the study was on individuals in palliative care facilities. For the purposes of this review, it was decided to exclude literature focusing exclusively on specific degenerative neurological conditions. The samples in these studies tended to include both people under and over 65 years living in a range of environments, including but not limited to aged care facilities. Finally, studies had to be published in peer reviewed journals and have extractable data (e.g., not a literature review, commentary or editorial) but were not excluded based on study quality (e.g., case studies through to randomized control trials were included). Only articles in English were included in the review.

The search had sensitivity in identifying the relevant population and the correct setting. To avoid relevant articles being excluded in the initial search phase, no age-related limitations were applied to the database searches. This lack of an age-related limitation may have contributed to the low search specificity for studies within the predefined age range (18–65 years). At title and abstract screening stages, 10% of titles and abstracts were independently screened by three authors (EGK, HJ and SO). Inter-rater agreement was acceptable between reviewers (93%) and any discrepancies about the inclusion or exclusion of articles were resolved through discussion and consensus with other authors.

The reporting of study selection was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Citation29) (see ). After all titles and abstracts were reviewed, 124 articles remained to be reviewed in full. Upon full text screening, 113 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 28 articles were excluded based on the age of participants (i.e., the mean age of the population was aged over 65 years, the age of participants was not specified, elderly and young participants were categorized together); 31 articles because the population did not reside in what the current review defined as residential aged care; 29 articles due to publication type (i.e., commentary, unpublished thesis, systematic review, written in a language other than English); 7 articles due to population (i.e., did not have a disability, focus was on degenerative neurological conditions living in a range of settings, population wasn’t adequately described); 12 articles because the study design did not separate the outcomes or experiences of young people with complex needs living in aged care from a different population (i.e., from those living in a different residential context or elderly participants); and 6 articles were unable to be accessed. Two additional articles were identified through forwards and backwards citation searches of the 124 articles that were full-text screened. Data was extracted from the remaining 11 articles (). Any disagreements and uncertainties regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles were discussed by the primary screening reviewers (EGK, HJ and SO), with the input of 2 independent review authors (JD and DW). Articles that were identified as meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria after full text screening were assessed by the review team (EGK, HJ, SO, JD and DW) for a final quality check.

Data was extracted from the studies across the following categories: (i) study characteristics (sample size, methodology, measures); (ii) participant characteristics (age, disability, gender, role); (iii) participant experiences; (iv) participant outcomes; and (v) recommendations for policy and practice. Experiences and outcomes were reported by participant, close others and/or staff members.

Results

Study characteristics

Of the studies included, 6 were from Australia, 2 were from Canada, 1 was from the USA, 1 was from Ireland and 1 was from the UK. Most of the studies included qualitative data. Specifically, 7 studies used a qualitative methodology, 3 used a mixed methods design and 1 study was quantitative. An overview of the characteristics of all studies included in the review is provided in . Qualitative methodology was appropriate in all cases and the research design was justified.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

In order to identify the quantitatively assessed outcomes, the measures utilized in the mixed methods and quantitative studies were mapped on to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Citation38). As can be seen in , the most commonly used outcome measures focussed on the person’s environmental context (i.e., care and support needs), activities and participation (i.e., resident choice) and multidimensional factors (i.e., level of awareness). The disparity of outcomes assessed and the variation in outcome measures used between studies is evident from this process. Of note, two studies reported on the administrative data available from the government on aged care facilities.

Table 2. Quantitatively assessed outcome measures mapped onto the international classification of functioning, disability and health.

Participant characteristics

A summary of the participant characteristics can be seen in . As per the exclusion criteria, all studies reported on participants between 18 and 65 years. Further, the participant samples in all the included studies were comprised solely of participants who were living, or had previously lived, in an aged care facility. The number of participants in the included studies ranged from 3 to 154 people. The perspective of the young person with a disability was reported in 8 of the 11 studies, and 9 studies reported on the perspective of both the young person and staff members or close others (i.e., next of kin or family members). All studies provided information about participants’ type of disability, with acquired brain injuries being the most common impairment. Three studies reported participants’ level of disability, while two studies measured participants’ support needs.

Table 3. Participant characteristics.

Experiences of residential aged care

The first aim of the review was to identify the experiences of young people with disability who are placed in aged care. For the purpose of this review, experiences were considered to be an individual’s “felt life”, including one’s emotional, physical and social encounters within residential aged care facilities.

Quantitative findings

Experiences of young people living in aged care identified by the quantitative studies included in the review were: a lack of community participation and social interaction (Citation7,Citation35), a lack of choice regarding meal time and meal content (Citation7,Citation36), age inappropriate activities (Citation7,Citation35) and living in an age inappropriate physical environment (Citation7,Citation36). A summary of the quantitative results are presented in .

Table 4. Quantitative research results.

Qualitative findings

Similar experiences of young people living in residential aged care were also identified in the reviewed qualitative literature (see for a summary of qualitative themes). Specifically, a lack of community participation and social interaction (Citation3,Citation33,Citation34,Citation37), age inappropriate activities (Citation3,Citation34,Citation37) and living in an age inappropriate physical environment (Citation3,Citation34) were identified as common experiences in qualitative studies. Additional experiences identified in the qualitative literature were issues surrounding mental health such as loneliness (Citation3,Citation33,Citation37), damage to psychological wellbeing (Citation1,Citation3,Citation33,Citation37) and experiencing an unsuitable care environment (i.e., level of care, staff expertise, resources and equipment) (Citation32). Additionally, one study found safety and treatment from other residents and staff members in aged care facilities was more positive when the young person’s disability was appropriately diagnosed, understood, and considered (Citation30).

Table 5. Author identified themes from qualitative studies.

The reviewed literature also commonly described a number of basic human needs that residential aged care facilities failed to provide for young people with disability. Specifically, the unmet needs identified were: privacy (Citation3,Citation34), physical (Citation3,Citation32,Citation34,Citation37), sexual (Citation34,Citation35), social (Citation3,Citation7,Citation33–Citation35,Citation37), nutritional (Citation34,Citation36), psychological (Citation3,Citation35,Citation37) and emotional support (Citation1,Citation3,Citation33,Citation35).

Outcomes of residential aged care

The second aim of this review was to identify the outcomes of young people with disability who are placed in aged care. For the purpose of this review, outcomes were considered to be consequences of living in residential aged care facilities.

Quantitative findings

Quantitative results demonstrated a number of undesirable outcomes associated with being placed in aged care, including limited independence or self-determination (Citation7,Citation36), institutionalization (Citation35) and the loss of valued life roles (Citation7). Unsurprisingly, the majority of young people placed in aged care reported a preference for alternative support and housing options (Citation7). In one study, nurses reported that, after residing in residential aged care, young people had little potential for discharge from aged care facilities (Citation35). However, more recent research suggests that young people are able to live more independently when provided the opportunity (Citation36) (see for a summary of quantitative results).

Qualitative findings

A number of negative outcomes were reported in the qualitative studies included in the review. Specifically, a lack of choice in regard to housing and meals (Citation1,Citation33,Citation34), limited independence or self-determination (Citation3,Citation33,Citation34,Citation37), preventable deaths (Citation32) and financial stress (Citation3,Citation30) were all identified outcomes for young people placed in aged care. See .

Implications for policy, practice and research

The final aim of the current review was to collate recommendations for policy, practice and research that address the issue of young people living in aged care. Ten out of the 11 articles included recommendations for policy and practice and 10 out of the 11 articles made recommendations for research. Despite the literature originating from a variety of countries, recommendations for policy and practice were comparable, further highlighting the international issue of young people living in residential aged care. A summary of policy, practice and research recommendations is presented in .

Table 6. Policy, practice and research recommendations.

Policy and practice suggestions were centred around improved access to information and services. Specifically, independent advocacy (Citation1) and supported decision making (Citation36) were proposed to assist individuals and their families to understand and navigate complex service systems and allow them to make informed decisions regarding housing options. In order to provide appropriate support for young people with disability, recommendations regarding systemic changes to rehabilitation (Citation33) and support services (Citation3,Citation34) were made. Recommendations for practice included increasing reassessment and rehabilitation opportunities (Citation1,Citation31,Citation33), increased care and support (Citation32,Citation34,Citation35) and the recognition and consideration of individual needs and choice within aged care facilities (Citation3,Citation30,Citation34–Citation36). Recommendations for increased expertise and training for nursing home staff were also common in the reviewed literature (Citation3,Citation7,Citation30,Citation33–Citation35). Furthermore, many studies recommended the development of age-appropriate accommodation for people with high and complex needs (Citation1,Citation31,Citation36,Citation37). Some studies made recommendations to adjust aged-care facilities to more adequately meet the needs of younger residents, such as the development of separate wings (Citation34,Citation35) or private rooms (Citation34). Other suggestions included environmental modifications to assist with independent movement, reduce disorientation and maximize choice making (Citation3,Citation7,Citation35,Citation36).

It is clear from the reviewed literature that further research is required to provide a stronger evidence base to inform policy and practice. General recommendations for future research included the use of replication studies (Citation33) and longitudinal research (Citation36). Whereas more specific recommendations included the investigation of barriers and facilitators to choice and service pathways (Citation30,Citation36), current discharge criteria (Citation1), perspectives of those who have avoided residential aged care (Citation1), preventable deaths (Citation37) and specific needs of young people who reside in residential aged care (Citation34,Citation35). It was recognized by the reviewed literature that more structured measures are required to gain more complete information on resident characteristics, experiences and outcomes of living in aged care (Citation35,Citation37). Finally, authors of the reviewed research recommended the implementation of outcome studies to evaluate the efficacy of services, and to document changes in health and wellbeing of young people placed in aged care facilities (Citation7,Citation37).

Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to explore the experiences and outcomes of younger people living in aged care. The reviewed literature highlights a clear convergence in regards to the negative experiences and outcomes of young people who live in residential aged care. Common experiences of living in aged care included a lack of community participation and social interaction, limited choice for everyday activities, as well as issues surrounding mental health (Citation1,Citation3,Citation33–Citation36). Further, it is critical to highlight that the results demonstrate the inability for residential aged care facilities to meet basic human needs that most people take for granted, such as privacy, physical, sexual, social, nutritional and emotional needs (Citation1,Citation3,Citation33,Citation34,Citation36). A number of undesirable outcomes, including a lack of independence and self-determination, financial stress and a lack of housing choice were commonly identified for young people placed in aged care (Citation1,Citation7,Citation33–Citation36). These findings align with previous research that has highlighted the vulnerability of young people who live in residential aged care (Citation22). Issues around self-determination, meaningful activity, social interaction, unmet needs and psychological wellbeing have been key concerns in previous research (Citation2,Citation21,Citation24). Findings from this review contribute to the emerging body of research which demonstrates the negative experiences and outcomes young people with disability encounter when they are inappropriately placed in residential aged care.

An important issue that emerged from the review was that young people with disability have a severe lack of choice in regard to their living arrangements (Citation1,Citation7,Citation33–Citation35). In line with previous research (Citation21,Citation22,Citation39), studies commonly reported that participants had no viable housing options other than residential aged care, available or offered to them (Citation1,Citation33,Citation34). This lack of options was often the case despite the presence of supportive families and was seen to be a result of housing not being affordable or adaptable (Citation1,Citation33,Citation34). The rights of people with disability have had a positive shift in relation to housing choice with the UNCRPD specifically stating that people with disability should be able to choose their place of residence and should not be obliged to live in a particular living arrangement (Citation18). However, the consistent finding that young people with disability are forced to live in residential aged care because there are no other viable options indicates that many young people with disability do not have equal housing opportunities, and ultimately reflects a violation of human rights for this population.

This review demonstrates that there is limited research into the specific characteristics of people with disability who are placed in residential aged care. Although all studies included in the review present information regarding type of disorder, only two studies specified the level of support required by young people living in residential aged care (Citation7,Citation36), and only two provided information regarding level of disability (Citation33,Citation34). The information available on the characteristics of young people with disability who live in aged care indicates that their support needs are similar to young people with disability who live in shared supported accommodation, suggesting that many young people placed in residential aged care could live more independently, if given the opportunity (Citation36). These findings further highlight the inappropriate placement of young people with disability in aged care considering their required level of support. Additionally, the literature in the current review provided only limited information regarding prior hospital admissions (Citation1,Citation36) and secondary health conditions (Citation7,Citation32); only one study discussed co-morbidities (Citation30). The research that reported secondary health conditions showed that young people in residential aged care are susceptible to secondary health conditions that can make them critically ill or result in death (Citation7,Citation32). Indeed, as demonstrated by this review, residential aged care can be damaging to young people’s health due to the unsuitable physical, social and care environment (Citation32,Citation35,Citation36). Furthermore, Carling-Jenkins et al. (Citation30) found that treatment from other residents and staff members in aged care facilities was more positive when a young person’s co-morbidity of Alzheimer’s disease was appropriately diagnosed and understood, signifying the importance of considering co-morbidities in a care environment. It is therefore important for future research to investigate and report specific disability characteristics including the support needs, secondary health conditions and comorbidities of young people in residential aged care in order to develop appropriate support services for this population.

The current review further highlights a clear gap in the literature surrounding the trajectory of young people with disability who are placed in aged care facilities. While the reviewed literature plainly demonstrates that living in residential aged care has a substantial negative effect on quality of life and physical health (Citation3,Citation33,Citation34), no studies were identified that investigated the long-term outcomes of young people placed in residential aged care. Previous research has identified residential aged care as contributing to young people becoming dependent or “institutionalized” due to the limited opportunities for rehabilitation (Citation21,Citation22). Additionally, Persson and Ostwald (Citation35) highlight the unknown psychological and social implications of being subject to the repetitive grief that young people in aged care experience due to the passing of other residents. Thus, the length of stay in aged care is likely to have ongoing and changing effects on health and wellbeing. Future research should endeavour to investigate how the experiences, outcomes and needs of this population change over time. This information would be valuable for the development of effective and sensitive policy initiatives that aim to support and transition young people to more independent living.

A range of study designs and assessment tools were used to investigate the outcomes and experiences of young people in aged care. The majority of studies identified in this review utilized a qualitative research design. Studies that rely on qualitative findings can be subject to biases because the findings are not tested to discover whether they are statistically significant, or due to chance. On the other hand, larger scale, quantitative findings, can be extended to wider populations with more certainty however can overlook complex experiences. Mixed methods research, where quantitative and qualitative methods are combined, is a valuable research design able to utilize the strengths of each method. It is therefore recommended that mixed methods research which is able to capture complexity of human experience, as well as evidence for generalizability, is utilized in future research (Citation40). Additionally, between studies included in the review, there were a range of outcome measures used to assess a variety of participant characteristics and outcomes. Interestingly, despite this heterogeneity, the studies had similar conclusions. This consistency of findings across varied designs and measures likely strengthens the evidence that aged care is an unsuitable environment for young people with disability to live. However, future research should aim to standardize outcome measures and replicate previous mixed methods study designs so that findings can be more easily validated, accumulated and compared.

Findings from the current review demonstrate a pressing need for policy and practice changes so that young people with disability have access to timely rehabilitation, housing and support. In order to support their right to independent living, young people with disability should be discharged from rehabilitation into an adapted property that meets their housing needs (Citation1,Citation7,Citation36). For this to be possible, a variety of housing alternatives must be made available to young people with disability (Citation1,Citation3). Emerging local and international social housing models indicate this reform is possible with significant financial investment (Citation27,Citation41). Immediate support is also required for young people currently residing within aged care facilities (Citation3,Citation7,Citation26,Citation34,Citation36). It is critical that rehabilitation services are accessible within residential aged care to support young people’s mental, social and physical health. Further, it has been shown that early and ongoing participation in rehabilitation plays a critical role in avoiding entry to aged care (Citation42–Citation44). Currently, international evidence suggests that there is limited funding allocated to extended rehabilitation services (Citation43). The NDIS, implemented by the Australian Government, is providing funding for young people to access support services, capacity building and housing options. With the introduction of the NDIS, younger people in aged care, or at risk of admission, are eligible for funding for the disability supports and equipment they need to live in the community. However, in order to avoid aged care or to move out of aged care, this cohort requires timely access to rehabilitation, skilled support coordination and accessible housing. Finally, the suggestion of a separate wing for young residents in residential aged care (Citation34,Citation35) does not resolve the issue that aged care facilities are not adequately set up or resourced to meet the needs of young people with disability. Indeed, there are currently a number of examples of co-locating young people with disability in aged care facilities and anecdotal evidence is that quality of life outcomes are still poor.

The current review highlights the need for a review process that follows up with young people placed in residential aged care to reassess and respond to their needs and potential for rehabilitation and community living. Multiple studies highlighted that young people with disability ended up in residential aged care because they had no choice (Citation1,Citation33,Citation34), and that they felt “stuck” with no way out of aged care (Citation3,Citation33). An effective review process would ensure that young people placed in aged care receive the ongoing rehabilitation and support required to transition to an independent living environment. Allied health professionals with specialist knowledge relevant to the needs of this cohort are needed to support an effective review process. Indeed, in a recent review of the literature, Knox and Douglas (Citation43) concluded that participation in ongoing rehabilitation programs can maximize independence and allow adults with severe acquired brain injuries to live in more home-like environments. In order to develop an effective review strategy, future research is required to investigate and report the characteristics (i.e., functioning, support needs, comorbidities and psychological health) of young people in residential aged care. This information would provide critical knowledge to develop resources to build the capacity of workers and families supporting young people in aged care, and the development of effective and sensitive policy initiatives.

A rigorous scoping review methodology using established methods was conducted to provide a systematic account of experiences and outcomes of young people living in aged care facilities. In order to be comprehensive, the current review included people with a range of disabilities (e.g., acquired neurological disorders, developmental, intellectual, physical or sensory disorders). Therefore, given the findings reflect a range of functional impairments and support needs across varied disabilities, limitations with respect to specific application to a single disability group need to be considered.

This review was conducted to provide a systematic summary and contribute to a greater understanding of the experience and outcomes of younger people with disability who are inappropriately placed in aged care. Findings demonstrate an overwhelmingly negative shared experience of living in an aged care facility. Young people’s emotional, social and physical health all suffer as a result of the inadequate support aged care facilities provide for young people with disability. There is a need for future research to investigate and report the disability level, support needs, secondary health conditions and comorbidities of young people in aged care facilities in order to develop alternative housing and support options. In order to form a strong evidence base, future research should endeavour to use consistent outcome measures and, where possible, utilize mixed methods designs. We further aimed to collate and discuss possible systemic changes that address the issue of young people living in aged care. It is clear from the current review that policy and practice changes are required to appropriately support young people with disability. The priority of these changes should be focussed on providing timely rehabilitation and more housing and support options that truly meet the needs of young people with disability.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Dr Liz Harris, the Senior Research Advisor at La Trobe University, for assisting us with the development of the search strategy utilized in the review.

References

- Barry S, Knox L, Douglas JM. 2018. “Time’s Up”: the experience of entering residential aged care for young people with acquired neurological disorders and their families. Brain Impair. 20(1):1–12. doi:10.1017/brimp.2018.13

- Cameron G, Pirozzo S, Tooth L. 2018. Long‐term care of people below age 65 with severe acquired brain injury: appropriateness of aged care facilities. Aust N Z J Public Health. 25(3):261–64. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00574.x

- Smith B, Caddick N. 2015. The impact of living in a care home on the health and wellbeing of spinal cord injured people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 12(4):4185–202. doi:10.3390/ijerph120404185

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Aged Care Data Clearinghouse request: younger people in RAC 2018. Canberra (Australia): Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: data from the national study of long-term care providers 2013-2014. Hyattsville (MD): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_038.pdf

- Winkler D, Farnworth L, Sloan S. 2006. People under 60 living in aged care facilities in Victoria. Aust Health Rev. 30(1):100–08. doi:10.1071/ah060100

- Winkler D, Sloan S, Callaway L. 2010. People under 50 with acquired brain injury living in residential aged care. Brain Impair. 11(3):299–312. doi:10.1375/brim.11.3.299

- Friesinger JG, Topor A, Bøe TD, Larsen IB. Studies regarding supported housing and the built environment for people with mental health problems: a mixed-methods literature review. Health Place. 2019;57:44–53. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.03.006.

- Schinasi LH, Auchincloss AH, Forrest CB, Roux AVD. 2018. Using electronic health record data for environmental and place based population health research: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 28(7):493–502. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.03.008

- Muenchberger H, Sunderland N, Kendall E, Quinn H. 2018. A long way to Tipperary? Young people with complex health conditions living in residential aged care: a metaphorical map for understanding the call for change. Disabil Rehabil. 33(13–14):1190–202. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.524275

- Sloan S, Callaway L, Winkler D, McKinley K, Ziino C. 2012. Accommodation outcomes and transitions following community-based intervention for individuals with acquired brain injury. Brain Impair. 13(1):24–43. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2012.5

- Mansell J, Beadle-Brown J. 2009. Dispersed or clustered housing for adults with intellectual disability: a systematic review. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 34(4):313–23. doi:10.3109/13668250903310701

- Evans GW, Wells NM, Moch A. 2003. Housing and mental health: a review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. J Soc Issues. 59(3):475e500. doi:10.1111/1540-4560.00074

- Kyle T, Dunn JR. 2008. Effects of housing circumstances on health, quality of life and healthcare use for people with severe mental illness: a review. Health Soc Care Community. 16(1):1–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00723.x

- Wong YII, Solomon PL. 2002. Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: a conceptual model and methodological considerations. Ment Health Serv Res. 4(1):13e28. doi:10.1023/A:1014093008857

- Cooper L, Verity F, Masters M. Housing people with complex needs: toolkit.. Adelaide (Australia): Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI); 2005.

- Kane RA. 1995. Expanding the home care concept: blurring distinctions among home care, institutional care, and other long-term care services. Milbank Q. 73(2):161e186. doi:10.2307/3350255

- UN General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: resolution/adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106; 2007 Jan 24. [accessed 2019 August 15]. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.html.

- Fries BE, Wodchis WP, Blaum C, Buttar A, Drabek J, Morris JN. 2005. A national study showed that diagnoses varied by age group in nursing home residents under age 65. J Clin Epidemiol. 58(2):198–205. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.07.001

- Tierney J. Submission to senate inquiry into aged care. Victoria (Australia); 2005.

- Duggan C, Lysack C, Dijkers M, Jeji T. 2002. Daily life in a nursing home: impact on quality of life after a spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 7(3):112–31. doi:10.1310/dl3p-pktj-pvff-8tqy

- Levack W, Thornton K. 2017. Opportunities for a meaningful life for working-aged adults with neurological conditions living in residential aged care facilities: a review of qualitative research. Br J Occup Ther. 80(10):608–19. doi:10.1177/0308022617722736

- McMillan TM, Laurie M. 2004. Young adults with acquired brain injury in nursing homes in Glasgow. Clin Rehabil. 18(2):132–38. doi:10.1191/0269215504cr712oa

- Riazi A, Bradshaw SA, Playford ED. Quality of life in the care home: a qualitative study of the perspectives of residents with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(24):2095–102. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.672539.

- Smith M. 2004. Under the circumstances: the experiences of younger people living in residential aged care facilities. Contemp Nurse. 16(3):188–98. doi:10.5172/conu.16.3.187

- National Disability Insurance Agency. COAG Disability Reform Council quarterly report. Canberra (Australia): National Disability Insurance Agency; 2019. https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/publications/quarterly-reports

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. Younger people in residential aged care - action plan. Canberra, Australia: commonwealth of Australia; 2019. https://www.dss.gov.au/disability-and-carers/programmes-services/for-people-with-disability/younger-people-with-disability-in-residential-aged-care-initiative

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. 2005. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 8(1):19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, DG A; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1093/ptj/89.9.873.

- Carling-Jenkins R, Torr J, Iacono T, Bigby C. 2012. Experiences of supporting people with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease in aged care and family environments. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 37(1):54–60. doi:10.3109/13668250.2011.645473

- Colantonio A, Howse D, Patel J. 2010. Young adults with traumatic brain injury in long-term care homes: a population-based study. Brain Impair. 11(1):31–36. doi:10.1375/brim.11.1.31

- Dearn L.“Permanent discharge”: deaths of people under 50 years of age in residential aged care in Victoria. J Law Med. 2011;19(1):53–68.

- Dwyer A, Heary C, Ward M, MacNeela P. 2017. Adding insult to brain injury: young adults’ experiences of residing in nursing homes following acquired brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 41(1):33–43. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1370732

- Hay K, Chaudhury H. 2015. Exploring the quality of life of younger residents living in long-term care facilities. J Appl Gerontol. 34(6):675–90. doi:10.1177/0733464813483209

- Persson DI, Ostwald SK. 2009. Younger residents in nursing homes. J Gerontol Nurs. 35(10):22–31. doi:10.3928/00989134-20090903-02

- Winkler D, Callaway L, Sloan S, Holgate N. 2015. Everyday choice making: outcomes of young people with acquired brain injury after moving from residential aged care to community-based supported accommodation. Brain Impair. 16(3):221–35. doi:10.1017/brimp.2015.32

- Winkler D, Farnworth L, Sloan S, Brown T. 2011. Moving from aged care facilities to community-based accommodation: outcomes and environmental factors. Brain Inj. 25(2):153–68. doi:10.3109/02699052.2010.541403

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2001.

- Strettles B, Bush M, Simpson G, Gillet L. Accommodation in NSW for adults with high care needs after traumatic brain injury. Sydney (Australia): Motor Accident Authority; 2005.

- Johnson R, Onquegbuzie AJ. 2004. Mixed methods research: a paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 33(7):14–26. doi:10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Wright CJ, Zeeman H, Kendall E, Whitty JA. What housing features should inform the development of housing solutions for adults with neurological disability?: a systematic review of the literature. Health Place. 2017;46:234–48. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.06.001.

- Groote M, Bickenbach J, Gutenbrunner C. 2011. The world report on disability: implications, perspectives and opportunities for physical and rehabilitation medicine. J Rehabil Med. 43(10):869–75. doi:10.2340/16501977-0872

- Knox L, Douglas JM. 2018. A scoping review of the nature and outcomes of extended rehabilitation programmes after very severe brain injury. Brain Inj. 32(8):1000–10. doi:10.1080/02699052

- Leung G, Katz PR, Karuza J, Arling GW, Chan A, Berall A, Fallah S, Binns MA, Naglie G. 2016. Slow stream rehabilitation: a new model of post-acute care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 17(3):238–43. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.10.016

Appendix. Medline Search Strategy

#Searches

1(aged adj3 care).mp.

2aged care facilities.mp.

3aged care facility.mp.

4aged care home.mp.

5aged care homes.mp.

6assisted living facilities.mp.

7assisted living facility.mp.

8((board adj3 care homes) and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

9((care adj3 home) and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

10((care adj3 homes) and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

11continuing care retirement center.mp.

12continuing care retirement community.mp.

13Convalescence home.mp.

14Convalescence homes.mp.

15Convalescent home.mp.

16Convalescent homes.mp.

17(consumer directed care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

18(custodial care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

19(elderly adj3 facilities).mp.

20(elderly adj3 facility).mp.

21(elderly adj3 home).mp.

22(elderly adj3 institution).mp.

23(elderly adj3 institutions).mp.

24(elderly care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

25(elderly care center and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

26extended care* facilities.mp.

27extended care* facility.mp.

28(geriatric adj3 facilities).mp.

29(geriatric adj3 facility).mp.

30(geriatric adj3 home).mp.

31(geriatric adj3 homes).mp.

32(geriatric adj3 institution).mp.

33(geriatric adj3 institutions).mp.

34(geriatric hospital and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

35high level residential care.mp.

36(homes adj3 aged).mp.

37((home adj3 care) and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

38((home adj3 community care) and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

39(hospice home and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

40(hostels and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

41(housing adj3 elderly).mp.

42housing/or housing for the elderly/

43(institutional care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

44(integrated community care system and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

45exp Long-Term Care/

46long term care home.mp.

47LTCF.mp.

48(long term care facilities and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

49(long term care facility and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

50(long term care residential care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

51exp Nursing Homes/

52(nursing institutes and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

53((old or aged or elderly) and (residential adj facilities)).mp.

54old age home.mp.

55(reablement and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

56(residential care home and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

57residential facilities/or assisted living facilities/or homes for the aged/

58RCFE.mp.

59(rest adj2 home*).mp.

60(rest home and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

61(restorative care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

62retirement home.mp.

63retirement homes.mp.

64(retirement adj3 facilities).mp.

65(retirement adj3 facility).mp.

66retirement village.mp.

67(sanatorium and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

68(senior adj3 home*).mp.

69(senior adj3 residence).mp.

70(senior adj3 residences).mp.

71sheltered housing.mp.

72skilled nursing facilities.mp.

73skilled nursing facility.mp.

74(skilled nursing unit and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

75(social care and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

76(social welfare unit and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

77(subacute care facilities and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

78(subacute care facility and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

79(supported living and (old or elderly or aged or geriatric or retirement)).mp.

8042 or 45 or 51 or 57

811 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 43 or 44 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 or 78 or 79

82cerebral hypoxia.mp.

83absence of limbs.mp.

84exp acute febrile encephalopathy/or exp akinetic mutism/or exp amblyopia/or exp amnesia, transient global/or exp auditory diseases, central/or exp basal ganglia diseases/or exp brain abscess/or exp toxoplasmosis, cerebral/or exp brain damage, chronic/or exp brain death/or exp brain diseases, metabolic/or exp brain edema/or exp brain neoplasms/or exp cerebellar diseases/or exp basal ganglia cerebrovascular disease/or exp brain ischemia/or exp carotid artery diseases/or exp cerebral small vessel diseases/or exp cerebrovascular trauma/or exp intracranial arterial diseases/or exp intracranial arteriovenous malformations/or exp “intracranial embolism and thrombosis”/or exp intracranial hemorrhages/or exp leukomalacia, periventricular/or exp sneddon syndrome/or exp susac syndrome/or exp vasculitis, central nervous system/or exp vasospasm, intracranial/or exp “diffuse cerebral sclerosis of schilder”/or exp encephalitis/or exp encephalomalacia/or exp epilepsy/or exp hydrocephalus/or exp hypothalamic diseases/or exp hypoxia, brain/or exp intracranial hypertension/or exp intracranial hypotension/or exp leukoencephalopathies/or exp neuroaxonal dystrophies/or exp sepsis-associated encephalopathy/or exp subdural effusion/or exp thalamic diseases/or exp central nervous system infections/or exp encephalomyelitis/or exp high pressure neurological syndrome/or exp hyperekplexia/or exp meningitis/or exp movement disorders/or exp ocular motility disorders/or exp pneumocephalus/or exp spinal cord diseases/

85exp anxiety disorders/or exp “bipolar and related disorders”/or exp “disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders”/or exp dissociative disorders/or exp elimination disorders/or exp “feeding and eating disorders”/or exp anorexia nervosa/or exp bulimia nervosa/or exp female athlete triad syndrome/or exp pica/or exp mood disorders/or exp depressive disorder/or exp cyclothymic disorder/or exp motor disorders/or exp neurocognitive disorders/or exp amnesia/or exp alcoholic korsakoff syndrome/or exp amnesia, anterograde/or exp amnesia, retrograde/or exp amnesia, transient global/or exp cognition disorders/or exp auditory perceptual disorders/or exp huntington disease/or exp cognitive dysfunction/or exp consciousness disorders/or exp delirium/or exp neurotic disorders/or exp paraphilic disorders/or exp personality disorders/or exp “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders”/or exp sexual dysfunctions, psychological/or exp sleep wake disorders/or exp somatoform disorders/or exp substance-related disorders/or exp “trauma and stressor related disorders”/

86acquired brain injury.mp.

87acquired neurological disease.mp.

88acquired neurological disorder.mp.

89amputation.mp.

90amputees.mp.

91amputees/

92ataxia.mp.

93(arthritis and (young person or young adult or young people)).mp.

94autism.mp.

95autistic.mp.

96back disorders.mp.

97(blind and (young person or young people or young adult or adolescent or adult)).mp.

98bone degeneration.mp.

99(exp bone diseases/or exp cartilage diseases/or exp fasciitis/or exp foot deformities/or exp foot diseases/or exp hand deformities/or exp jaw diseases/or exp ankylosis/or exp arthralgia/or exp arthritis/or exp arthritis, infectious/or exp arthritis, juvenile/or exp arthritis, psoriatic/or exp arthritis, rheumatoid/or exp chondrocalcinosis/or exp gout/or exp osteoarthritis/or exp periarthritis/or exp rheumatic fever/or exp sacroiliitis/or exp spondylarthritis/or exp arthrogryposis/or exp arthropathy, neurogenic/or exp bursitis/or exp chondromatosis, synovial/or exp contracture/or exp crystal arthropathies/or exp femoracetabular impingement/or exp hallux limitus/or exp hallux rigidus/or exp hemarthrosis/or exp hydrarthrosis/or exp joint deformities, acquired/or exp joint dislocations/or exp joint instability/or exp joint loose bodies/or exp metatarsalgia/or exp nail-patella syndrome/or exp osteoarthropathy, primary hypertrophic/or exp osteoarthropathy, secondary hypertrophic/or exp patellofemoral pain syndrome/or exp shoulder impingement syndrome/or exp synovitis/or exp temporomandibular joint disorders/) and (young person or young people or young adult).mp.

100(exp bone diseases/or exp cartilage diseases/or exp fasciitis/or exp foot diseases/or exp digestive system diseases/or exp stomatognathic diseases/or exp respiratory tract diseases/or exp otorhinolaryngologic diseases/or exp eye diseases/or exp male urogenital diseases/or exp cardiovascular diseases/or exp “hemic and lymphatic diseases”/or exp “congenital, hereditary, and neonatal diseases and abnormalities”/or exp “skin and connective tissue diseases”/or exp “nutritional and metabolic diseases”/or exp endocrine system diseases/or exp immune system diseases/or exp animal diseases/or exp occupational diseases/or exp “wounds and injuries”/) and (young person or young adult or young people).mp.

101bone formation.mp.

102exp Brain Injuries/

103brain injur*.mp.

104cerebral hypoxia.mp.

105(cognitive impairment and (young person or young people or young adult)).mp.

106(cognitively impaired and (young person or young adult or young people)).mp.

107(communication impairment and (young person or young adult or young people)).mp.

108chronic condition.mp.

109cognitive communication disorders.mp.

110complex health condition*.mp.

111complex needs.mp.

112deafblind.mp.

113(deaf and (young person or young people or young adult)).mp.

114(deafened and (young person or young adult or young people)).mp.

115(deformities adj3 limbs).mp.

116developmental disabilities.mp.

117developmental disability.mp.

118developmental disorder.mp.

119developmental disorders.mp.

120dual sensory.mp.

121epilepsy.mp.

122fibromyalgia.mp.

123(hard of hearing and (young person or young adult or young people)).mp.

124head injur*.mp.

125hearing disabilities.mp.

126hearing disability.mp.

127exp hearing disorders/and (young people or young person or young adult).mp.

128intellectual* disab*.mp.

129intracranial injur*.mp.

130learning disabilities.mp.

131learning disability.mp.

132learning disabled.mp.

133Mentally Disabled Persons/

134mentally disabled.mp.

135mentally handicapped.mp.

136monoplegic.mp.

137(musculoskeletal disease* and (young person or young people or young adult)).mp.

138(musculoskeletal disorder* and (young person or young people or young adult)).mp.

139(musculoskeletal injur* and (young person or young people or young adult or adolescent)).mp.

140neuropsychiatric disease*.mp.

141neuropsychiatric disorder*.mp.

142paraplegic.mp.

143persons with hearing impairments/and (young person or young people or young adult).mp.

144physical disabilities.mp.

145physical disability.mp.

146physical handicap.mp.

147physical impairment.mp.

148physically disabled.mp.

149physically handicapped.mp.

150physically impaired.mp.

151progressive neurological disease.mp.

152progressive neurological disorder.mp.

153quadriplegic.mp.

154exp Spinal Cord Injuries/

155(stroke and (young adult or young person or young people)).mp.

156scoliosis.mp.

157speech disabilities.mp.

158speech disability.mp.

159speech disorder.mp.

160speech disorders.mp.

161spina bifida.mp.

162spinal cord injur*.mp.

163tetraplegic.mp.

164traumatic brain injury.mp.

165exp Vision Disorders/and (young people or young person or young adult).mp.

166visual disabilities.mp.

167visual disability.mp.

16884 or 85 or 91 or 99 or 100 or 102 or 127 or 133 or 154 or 165

16982 or 83 or 86 or 87 or 88 or 89 or 90 or 92 or 93 or 94 or 95 or 96 or 97 or 98 or 101 or 103 or 104 or 105 or 106 or 107 or 108 or 109 or 110 or 111 or 112 or 113 or 114 or 115 or 116 or 117 or 118 or 119 or 120 or 121 or 122 or 123 or 124 or 125 or 126 or 128 or 129 or 130 or 131 or 132 or 134 or 135 or 136 or 137 or 138 or 139 or 140 or 141 or 142 or 143 or 144 or 145 or 146 or 147 or 148 or 149 or 150 or 151 or 152 or 153 or 155 or 156 or 157 or 158 or 159 or 160 or 161 or 162 or 163 or 164 or 166 or 167

17080 and 168

17181 and 169

172170 or 171

17380 or 81

174168 or 169

175173 and 174

176limit 175 to yr = “2014– 2018”