ABSTRACT

This article examines the appetite for historic preservation in Miami within broader colonialist and moralising discourses of ‘civilising’ the wilderness and of aesthetic ‘merit’ that go back to the foundation of the city. It argues that a growing sense of anxiety, stoked by increasing waves of migration into Miami, is at the heart of this emphasis upon historic preservation, but is also at work in the delineation of what types of structure merit preservation in local law and policy. It analyses the effects of these policies upon peoples of colour, and argues that the effects of Jim Crow segregation law can still be seen in Miami’s cityscape through the present-day delineation of which structures ‘count’ as historic, and therefore worth preserving for the future.

Introduction

Early in 2018, I was living in Miami, conducting ethnographic research amongst the sizable Cuban diaspora there. One of my interlocutors invited me to her teenage daughter’s upcoming quinceañera party,Footnote1 which would include a photoshoot at the Ancient Spanish Monastery towards the north of the city. The venue has become a popular location for engagement photoshoots and the like for its perceived capacity to ‘inject history’ into any scenario. The monastery itself was in fact originally constructed in the twelfth century in northern Spain, and subsequently purchased by a wealthy American businessman in 1925, dismantled, shipped to New York, and then stored in large wooden crates for several decades, owing to the businessman losing much of his money in the Great Depression. The monastery was eventually purchased again and re-assembled in the 1950s in Miami, and today is considered by many residents to be one of the most ‘historic’ places in the city.

A few months later I decided to visit again with Jon, a man in his 40s who took a keen interest in local history and liked to give walking tours to tourists in his spare time. As we wandered around the cloisters, I mentioned offhandedly that for me, as a European woman who has spent much of her life in and out of medieval buildings, it was slightly odd to be in a ‘medieval building’ that smelled so new. I was more used to a musky smell of rising damp: a sensorial dimension of a building’s historicity that could not be stored in a crate and re-assembled in tropical Miami. Yet for Jon, who had long desired to travel to Europe and tour various ancient European cities, this comment seemed dismissive. ‘The reason so many people want to get married here,’ he told me, ‘is because it’s important for the future to have a good history to ground itself upon. And you can’t get the smell into a photo anyway.’

As my time in Miami continued, I increasingly became aware that for many of my acquaintances in the city, this question of grounding the future upon history was of crucial importance. Time and time again, I found myself struck by how frequently the idea of history (which I will refer to throughout this article as ‘historicity’) was cited, and indeed mobilised, in visual and performative ways to various political and economic ends by different groups of people across the city. I started to notice how many buildings had (or were applying to get) plaques designating them as ‘historic’ (which I will refer to throughout this article as ‘historicness’, following my interlocutor Jon, meaning the ‘quality of being historic’). Whole neighbourhoods were becoming established as ‘historic’, and such terminology often (although not always, as we will see) had clear definition in law and local policy. Yet, as anthropologists have long recognised, the idea of ‘history’ is a social construction, and ‘historicity’ in this vein describes ‘a human situation in flow, where versions of the past and future (of persons, collectives or things) assume present form in relation to events, political needs, available cultural forms and emotional dispositions’ (Hirsch and Stewart Citation2005, 262).

Over a coffee with Jon a few months later, I quizzed him for his take on this, and, delighted that I now seemed to be taking the idea of the ‘historicness’ (his word, meaning the status and acknowledgement of a place as ‘historic’) of Miami a little more seriously, he proceeded to explain how history in the ‘New World’ is an important aspect of future-making endeavours.

‘One has to consider that, in this country specifically, growth in the name of progress constantly changes the landscape, so history implies we are writing as we go along so as not to forget our beginnings. And we need to construct and document those beginnings carefully.’

Even by American terms, Miami is a very new city. Until just over a century ago, the southern tip of Florida was largely uninhabited, and mostly made up of swampland (the Everglades). It was one of the last colonial frontiers of nation-making for the American state; it ‘belonged’ to the Spanish until 1821, who themselves had seized traditional Seminole land. The three Seminole wars between 1818 and 1858 ultimately resulted in the Seminole people retreating into the swampland of the Everglades to what was called an ‘Indian reserve’, while a newly built railroad connected the Atlantic coast of Florida with Georgia to the north and beyond. With the expansion of the railroad down to southern Florida, Miami was finally incorporated as a city (of 362 inhabitants) in 1896, and started to prosper in the 1920s as homesteaders moved southwards to cultivate large parcels of land for farming. The population of Miami later boomed in the 1950–1960s, in part due to a large influx of Cuban migrants fleeing the Revolution in 1959.

In the decades since, Miami has expanded significantly, becoming home to numerous waves of inward migration from Latin America and the Caribbean. As an acquaintance of mine once put it to me, ‘in many ways Miami is the final frontier here in the U.S., more so than Alaska, and we’re still civilising it to be honest.’ An implicit sense of ‘threat’, or of precarity – perhaps from those frontier beginnings – is ever-present in Miami. Many of my interlocutors worried about successive new peoples and cultures arriving in the city and erasing or replacing their own history; others were concerned about rising sea levels due to global warming affecting the value of their property. I argue that this anxiety is inherent to the growing moves to ‘preserve’ and designate historic sites across the city that are the focus of this article.

Local historian Arva Moore Parks founded Miami’s historic preservation trust in the 1970s, and has stated,

‘when I began writing Miami history and working to preserve its important places, I called on all these memories of people, places and events to help me. When I write about Miami, I always include everyone in the story. Each day, I realize more and more that there is no better place to live if you want a jump start on America’s future’ (see Reese Citation2017).

Coral (Gables) under threat

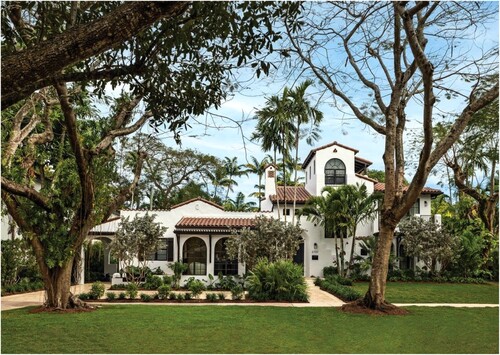

During the Florida land boom in the early 1920s, realtor George Merrick purchased a large parcel of land just west of downtown Miami, and began to construct a planned community based on the popular early twentieth century ‘City Beautiful’ movement. This new community, which was named Coral Gables (sometimes referred to simply as ‘the Gables’), was envisioned as ‘a most extraordinary opportunity for the building of "Castles in Spain"’ (Parks Citation2006) and had at its heart the aesthetic vision central to the ‘Mediterranean Style’. The Mediterranean Revival style drew inspiration from various European architectural traditions, combining elements from Italy, Spain, and other Mediterranean countries to evoke a sense of antiquity and romanticism, giving rise to imaginative and elaborate buildings with extensive use of stucco, arches, courtyards, and other decorative elements. The style also had enormous image-making value at a time when Miami was increasingly becoming a tourist destination; as such, Coral Gables’ turrets and porticos often featured on postcards of Miami, earning the nickname ‘City Beautiful’, which is still to be found on street signage and furniture to this day ().

Merrick contended that the houses in Coral Gables were to Miami what Manhattan’s steel skyscrapers were to New York, with both representing ‘great native American architecture’ (in Connolly Citation2019, 48). Of great importance was the prominence given to the idea of visual beauty; Merrick believed that in Coral Gables life might be richer and finer ‘because beauty has been put to its right uses,’ by which he means that the visual aesthetic in turn draws on an older (colonial) notion of European antiquity-as-beauty, or as he put it, ‘the kinship of this architecture to the older excellencies’ (Merrick Citation1922). Instant antiquity was the goal of this aesthetic movement, arguably because this in turn helped to make material a fantasised shared history or origin myth that reached back to Old World pedigree; indeed, similar architectural tropes were mobilised in parallel endeavours elsewhere in the United States at around the same time (Chacón Citation2001). While the style was most frequently applied in Floridian coastal resort towns, it was also popular in Oklahoma, Montana, California, Oregon, Wisconsin and New York. From its infancy, then, Coral Gables was designed to be old, as a frontier project of antiquity-as-legitimation. This language of legitimation and ‘civilising’ remains to this day and can be found in local council publication titles such as ‘Miami, from wilderness to Metropolis’ (Ammidown and Rodriguez Citation1982).

In the creation of this immediate historicity, Merrick also effectively created a community united through a shared positionality as ‘restorers’. Owners of these (very valuable) Coral Gables homes become members of a larger kin network, in a sense: they are preservers and protectors of a shared history that must be handed down to the next generation. As Jim – the director of a Coral Gables Museum which conducts research and also liaises closely with the historic preservation society housed upstairs – explained to me, the real interest in ‘self-organising’ as a unit to promote historic preservation within Coral Gables started in the 1980s, broadly around the same time as an influx of Cuban migrants to the nearby district of Little Havana (which borders Coral Gables) fuelled portrayals of Miami as a home to ‘cocaine cowboys’ in films like ‘Scarface’ (1983), starring Al Pacino. ‘That was really when George Merrick’s vision of a ‘city beautiful’ was at its lowest,’ Jim told me, ‘but fortunately more recently there’s been a big interest again in returning to that vision.’ He continued by describing how incoming residents to the conservation area were screened for suitability, which he defined as ‘a clear awareness that history is not just about preserving, but also resurrecting.’ For Jim and his fellow preserver-citizens, ‘the city will never go back to the way it once was, but we can stop it from going in the wrong direction in the future.’

One way of ensuring this ‘clear awareness of history’ amongst local residents is through strict adherence to aesthetic codes and rules, which determine with a great degree of precision what architectural beauty should look like in Coral Gables. There exist several publications that detail the extent of how preservation and restoration activities should be undertaken. As one guide explains,

‘Miami is young by many standards; most of its buildings and infrastructure were built in the twentieth century. Nevertheless, memory plays a powerful role here. Historic buildings and districts communicate something tangible about the context and identity of a region accustomed to rapid growth and transformation. In this sense, historic preservation reinforces a sense of place, but also a sense of continuity essential to future growth. This continuity requires a sense of obligation to and interconnectedness with the surrounding community. Beyond the cultural role of preservation, there is an aesthetic value to preserving older buildings, and an economic one as well. Historic buildings are valued for their singular qualities, and their appearance, a factor often reflected in property values’ (Shulman Citation2021, 5, emphasis added).

In this regard Coral Gables arguably resembles what Sharon Lee Dawdy (Citation2016) has called the ‘critical nostalgia’ of patina in New Orleans’ aesthetic landscape. The aesthetic of antiquity, which Dawdy calls patina, becomes a medium of aesthetic value perceived to have accumulated throughout time, representing a palimpsest of New Orleans sociality. I would add to this that the decisions over what counts as being of historic value, and therefore of what inherently can imbue ‘patina’, is also a conscious curation of this social palimpsest: the definition and ongoing preservation or restoration of aesthetic antiquity curates a particular narrative of where a place has come from, and who built it. Just as ‘Frenchness’ becomes a hegemonic aesthetic within New Orleans, evoking a particular colonial history and a shared view of local history in opposition to more Anglo settlements nearby, so, I argue, does a romanticised ‘Spanishness’ or ‘Mediterranean’ quality draw upon particular lineages that connect Miami with a European identity () in the face of historic and contemporary connections with nearby Caribbean and Latin American cultures. It is in this vein that Coral Gables speaks to Dawdy’s conception of ‘critical nostalgia’ as ‘not only a political aesthetic but a political force flowing through alternative circuits of value that are both moral and material’ (Citation2016, 7). Just as a preoccupation with patina in New Orleans signifies both the emergence and submergence of the past in the present, so too do anxieties about preservation and restoration in Coral Gables speak to a wider urban landscape in Greater Miami that has silenced other pasts in favour of political assertions of who is included in the present and future of the city.

Sundown in Overtown

Throughout its history, Miami has been among the most racially segregated cities in the United States. While Coral Gables, or the ‘city beautiful’, was being constructed in the 1920s, just two miles to the east was ‘Colored Town’, which since the late nineteenth century had been home to the substantive Black population of workers that were employed in the construction projects linked to South Florida’s boom period. 168 of the 362 men who voted for the incorporation of Miami as a city in 1896 were counted as ‘coloured’, but Jim Crow laws at the time dictated they had to live in a separate part of town, on the other side of the railroad tracks they had been brought in to build (Smalls and Isaiah Citation2021). These segregation laws also imposed curfews upon people of colour, meaning that the growing population of Black residents of Colored Town that worked in the booming leisure businesses in Downtown Miami and Miami Beach had to make sure they had headed back over the rail tracks to Colored Town (which later became ‘Overtown’) before sundown. ‘Sundown towns’ were the norm in much of the American South and were vigorously enforced by both vigilantes and the police (Loewen Citation2005; Connolly Citation2006). Significantly though, the area now known as Overtown, along with another nearby neighbourhood called Coconut Grove (which I will return to later in this article), were the first two continuously populated districts of Greater Miami, housing most of the workers that subsequently constructed the other built-up areas of the city.

Although segregationist policies encouraged a dualistic black/white divide, the Black population of Miami was always heterogeneous, with the first migrants coming from the Bahamas to labour on farms from the 1880s, joined in the early twentieth century by African-American descendants of slaves in Georgia and South Carolina, who moved south to work on the newly opened plantations and construction projects (Gosin Citation2019; Dunn Citation1997). Subsequent migration also brought groups of Haitians and West Indians to Miami, as well as Afro-Cubans (Aja Citation2016). Indeed, ‘a Blackness that exceeds the nation-space has been integral to Miami’s formation’ (Francis and Harris Citation2020, 4), and while these diverse cultural heritages were typically conflated as ‘negro’ in records, they are still visible in several distinct architectural styles, such as the ‘shotgun shacks’ and ‘conch cottages’ in Coconut Grove and Overtown, and the ‘gingerbread style’ of Little Haiti (Miorelli Citation2015).

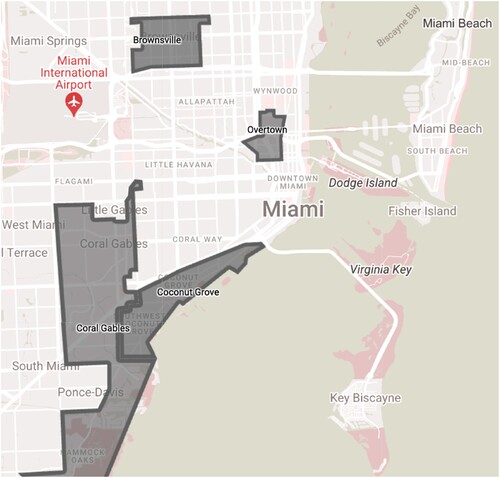

Overtown was also an affluent city; it was home to one of the first Black millionaires in the American South, D. A. Dorsey, the son of former slaves in Georgia who became a very successful businessman, banker and philanthropist. Yet many of the buildings in Overtown, which dated back to the 1880s, have been described as ‘simple’, ‘nondescript’ or ‘vernacular’ in style, serving as practical homes and businesses without overt emphasis on decoration (Fields Citation1998, 325). In May 1937, George Merrick (the visionary behind Coral Gables and also the chairman of the Dade County Planning Board) proposed ‘a complete slum clearance effectively removing every negro family from the present city limits’; this removal, Merrick asserted, was ‘a most essential fundamental’ for the achievement of ambitious goals the planning board laid out for Miami (Merrick Citation1937, 11). Over the 1940s, hundreds of Black families were moved north to so-called ‘Liberty City’ and the adjacent ‘Brownsville’ (see ), which were housing projects designed to address the problems of overcrowding and disease seen as stemming from Overtown’s architecture. Policies of redlining throughout the 1930–1940s restricted access to loans and mortgages for residents of poorer, older and Black neighbourhoods, further contributing to negative views on the overall ‘worthiness’ of historic buildings in Overtown, which were categorised as ‘hazardous’ and in various states of ‘physical decay’ (Mohl Citation1987, 3).

Figure 3. Annotated map of Miami showing relative positions of Coral Gables, Coconut Grove, Brownsville (including Liberty City) and Overtown (formerly Colored Town).

Like other urban Afro-descendant neighbourhoods, Overtown then became a victim of Eisenhower-era federal highway plans to connect central business districts with the newly developed suburbs (Mohl and Rose Citation2012). Much of the neighbourhood was bulldozed in the 1960s to make way for the new I-95 interstate highway, which essentially runs straight through the middle of the district. These highways belonged to a political project of progress and modernity-making, but their construction led to the destruction of the cultural and economic heart of Overtown, marking a shift in tone from the overt racial segregation of Jim Crow to a more ‘progressive’ and ‘less obvious form of racism tied to urban development and growth liberalism’ (Connolly Citation2006, 25). An estimated 40,000 Black residents were displaced (Aranda, Hughes, and Sabogal Citation2014, 18) from the commercial and cultural heart of the area once dubbed the ‘Harlem of the South’ (Dluhy, Revell, and Wong Citation2002, 76), wrapped up in a broader infrastructural political project of future-making (and whitewashing) that has been called the ‘calculus of highway engineering’ (Rose Citation1990, 107).

Overtown became (and remains) one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the United States, associated with high rates of crime, homelessness, and drug use. I was frequently warned by (white, middle-class) interlocutors not to venture there, as it was ‘far too dangerous’ for someone ‘like me’. Jim, the director of a Coral Gables museum that we encountered in the previous section, described it to me as Miami’s answer to Los Angeles’s infamous ‘tent city’, saying he didn’t know exactly where it was, and ‘nor would [he] care to know.’

Much of the demolition of some of the oldest buildings in Miami continued through the 1960s and beyond by means of the assertion of new ‘building standards’, which were used to delineate properties that did not adhere to more ‘modern’ standards of living. One first-hand account from a former Overtown resident recalls the day these building standards were enforced by demolishing a whole street of original ‘shotgun shacks’ dating back to the late nineteenth century:

‘All the little shotgun shanties but two were torn down and there was one white guy on a tractor or bulldozer, another white guy standing on the street and … the one on the bulldozer asked the guy on the street, ‘You want me to get these now?’ The guy on the street said, ‘No, you can get those after lunch’ … I cried because there was one white man who had the power to say to another white man ‘Finish wiping out this Black history after lunch’’ (in McCartney Citation1997, 42).

It is in light of these threats of demolition that a group of local residents has attempted to gain ‘historic’ status from the City Preservation Board, which in turn would add a layer of legal protection to the remaining structures in the neighbourhood. Most Miamians in fact know the district as ‘Historic Overtown’, and many of my interlocutors from across Miami assumed this meant the neighbourhood enjoyed this protected status, as do the Bay Shore Historic District, Downtown Miami Historic District, Lummus Park Historic District, and South River Drive Historic District (all located closely nearby). In fact, Overtown is not designated as a historic district, and the sign calling it such is street art painted by a local resident (). For the buildings that have thus far been saved, much of the credit belongs to local historian and activist Dr Dorothy Fields, who founded the Black Archives located in Overtown. She has spoken of her own drive to preserve Black history in Miami within an idiom of family genealogy, saying

‘I thought that if a black man built this, he built it for us. I felt obligated to restore the building. I think of those buildings as footprints that connect generations of the past, whom we shall never see, with the generations of the future, whom we shall never see’ (interviewed in 2007; quoted in Lin Citation2010, 131).

Figure 4. Street art on overpass demarcating ‘Historic’ Overtown. Image copyright © Pietro from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Miami_FL_Overtown_3rd_Ave.jpg.

‘Real estate developers are keen on acquiring large parcels of land so that they can be developed and then be gentrified. I have even had repeated offers for me to literally move the wooden house to another site so that developers can buy the whole street. That’s why we want to try to get the historic recognition in the first place.’

‘You see there is history, and then there is our history, and not all histories get treated the same. On the Preservation Board they call it ‘contributing’ and ‘non-contributing’. I just feel the government don't [sic] want it to be historical point blank.’

Designating the city

In Miami-Dade County, the Historic Preservation Board has the authority to designate local historic sites ‘to protect, enhance and perpetuate properties of historical, cultural, archeological, paleontological, aesthetic and architectural merit’ (City of Miami Citationn.d.). According to the Board’s website, their objectives involve ‘recognizing the locations, sites and resources from our history that have survived, determining their significance and worth to us now, and maintaining, utilizing and caring for these important locations, sites, and resources to ensure their survival in the future’ (ibid.). Designated properties cannot be changed without prior permission from the Board, and are also eligible for the County’s ‘historic preservation ad valorem tax exemption program.’ Designation can be awarded to any building that is more than fifty years old, providing it also meets the other ‘standards’ set out in the design guidelines, last updated in 2016 (City of Miami Citation2016).

In one informal meeting of the Board that I attended alongside Jonah, a conversation started up about the informal ‘historic’ sign that had been painted onto the bridge demarcating the boundary of Overtown (). It was felt by some members that this was further evidence of the fact the district could not be designated as sufficiently ‘historic’, due to the fact such ‘graffiti’ clearly was far from in keeping with the design guidelines for historic areas. These guidelines dictate that signs must ‘conserve and protect scenic beauty and the aesthetic character of the City by reducing visual clutter and optimizing communication’ (ibid., 47). In determining whether a sign could qualify as ‘historic’, the Board’s guidelines state consideration should be given if the sign is:

Associated with historic figures, events or places.

Significant as evidence of the history of the product, business, or service advertised.

Significant as reflecting the history of the building or the development of the historic district (A sign may be the only evidence of a building’s historic use).

Characteristic of a specific historic period, such as gold leaf on glass, neon, or stainless steel lettering.

Integral to the building’s design or physical fabric, as when a sign is a part of storefront made of Carrera glass or enamel panels, or when the name of the historic firm or the date are rendered.

Outstanding examples of the sign maker’s art, whether because of their excellent craftsmanship, use of materials, or design.

Recognized as local landmark, because of its prominence and popular recognition as a focal point in the community.

Assists in defining the character of a district, as for example marquees in theater districts, or prominent neon signs associated with the proliferation of motels dependent upon the tourism industry (City of Miami Citation2016, 23–6.4, italics added).

In other words, the design guidelines dictate a particular aesthetic framework, which are perhaps easier to comply with in some neighbourhoods than in others. Pete, a retired lawyer in his 70s who lives in Coral Gables and takes a keen interest in historic preservation locally, explained that in Coral Gables they ‘try to keep it European-looking and pretty. It’s harder and harder as more people come in. But I’m American and it’s important that someone continue that heritage.’ For a district like Coral Gables that was explicitly designed to project an idealised version of European historicity, this is arguably an altogether easier task than it is for a neighbourhood like Overtown, which was constructed primarily by a Bahamian workforce for whom the structures had to serve a more practical purpose, and whose budget dictated different or ‘simpler’ building materials.

According to the Historic Preservation Board,

‘in most instances the value of historic properties increase after designation, and properties within historic districts often have higher property values than comparable neighborhoods in close proximity. Buyers often search out for historically designated neighborhoods because they know that their own investments will be protected from intrusions into the neighborhood that are out of character with the district’ (City of Miami Citationn.d.).

It is my argument here that this delineation of aesthetic or architectural ‘merit’ now forms a more invisible but no less potent battleground that sits within a struggle for voice and recognition by peoples of colour in the American South dating back centuries. In Jonah’s own words, ‘it’s sort of like Jim Crow is now a more unwritten rule of law.’ The local decision to paint up the word ‘Historic’ in front of Overtown () on the overpass can be viewed as a physical assertion of identity and history onto the very space that the City attempts to regulate and specify through its preservation and design guide efforts. Michel de Certeau (Citation1984) suggests that by walking the city, pedestrians write their own trajectories onto the cityscape, acting as a mass made of subjects that escape any planned or regulated scheme of the city. Arguably here, the local attempts to assert ‘historicness’ onto space acts in a similar way, using public space to mobilise alternative narratives of historicity – of past and future – in competing ways.

Time against race

Preservation is a social practice, not merely a technical discipline, and belies the broader normative ideologies and hegemonies at work in society. To quote Michel Rolph Trouillot, the act of deciding what ‘counts’ as history ‘shifts us from ‘what happened’ to ‘that which is said to have happened’’ (Citation2015, 2–10), and history or historicity is in a constant state of social production and renewal. What history is, Trouillot continues,

‘changes with time and place […] history reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives. Only a focus on the process can uncover the ways in which the two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through the overlap can we discover the particular exercise of power that makes some narratives possible and silences others’ (ibid., 25).

In Miami, ‘historic’ structures are given legal protection as well as financial benefits through tax exemptions, in a manner aligned with what Foucault termed the ‘governmentalization of the state’ (Citation2007, 109), where relations come to be ‘established between political rule and other projects and techniques for the calculated administration of life’ (Miller and Rose Citation2008, 69). Meanwhile, in Miami heritage is viewed as more intangible, belonging to a less formalised domain (at least when it comes to questions of demolition and legal protections). ‘Soul food’ restaurants in Overtown, for example, are celebrated in local media and tourist boards as places of great Black cultural ‘heritage’ (Mailander Farrell Citation2021), at the same time as applications are made to demolish the building housing that restaurant. To quote Pete, the Coral Gables ‘native’ lawyer who in his retirement runs a local history appreciation group,

‘the difference between historic and heritage is that history is when something significant has happened in a particular place, whereas heritage is a much broader term and really means more of a cultural flow which can include history. The interesting thing that’s happening in Miami now is that many of the people whose cultures set up Miami in its infancy are dying, while lots of new groups are coming in here that don’t know about that history. I guess the problem is that it’s not a shared history.’

Hobsbawm and Ranger’s (Citation1983) articulation of the ‘invented’ nature of tradition and Hewison’s (Citation1987) influential account of the ‘Heritage Industry’ have been important in developing a critical paradigm for heritage studies that understands the grand history of European heritage within the domains of museums, historic preservation, and folklore as integral to the constitution of the modern state and its political economy. However, in the ethnographic examples provided in this article, we see how some histories and heritages are elevated in the very act of silencing others. In this sense, in Miami, historic preservation is an ideological act and a key way of defining quite literally what the future of the city looks like (as well as who is represented in that vision). ‘Heritage, like its older sister, cultural property, is a tangle of ideology and expectation,’ as Heidy Geismar reminds us; an ‘analytic term and a tool of governance; a category that allows us to understand the power dynamics involved in the selective recognition of identity, often in material form’ (Citation2015, 72). The social norms that determine what ‘counts’ as historic, such as the design guidelines discussed earlier in this article, evoke Arjun Appadurai’s formulation of culture as ‘a dialogue between aspirations and sedimented traditions’ (Citation2004, 84), responding to and seeking to ‘regulate conditions of social change’ (Citation1981, 218).

In the case of Miami, it becomes quite clear that definitions of ‘historicness’ map onto frameworks of aesthetic ‘merit’, which in turn signal particular normative (and ethnocentric) assumptions about what type of architecture is valuable to future society. Land and its uses serve as expressions of acceptable governance. Under Jim Crow laws, the citizens of Miami established a ‘sturdy and supple infrastructure for white supremacy that remains very much in place’ (Connolly Citation2019, 3). This was arguably then propelled into future decades after the civil rights movement through zoning rules, preservation boards, and realtors, which continue to protect the whiteness of communities at the expense of other populations. The picture of American history presented by historic sites continues to undervalue the experiences and contributions of immigrants, working people, and communities of colour, although this may often be rendered less visible through use of other terms like ‘simple’, ‘vernacular’, and so on. We encounter such reference to aesthetic merit even in scholarly research, such as this description of attempts to preserve other historic sites across the United States, which ‘are not only undistinguished as architecture but have also been poorly built, altered, and generally used hard [posing] the problem of how to protect places which matter more for their stories than their material or aesthetic values’ (Kaufman Citation2009, 17). At its root, then, ‘heritage’ helps to prop up an essentially conservative ideology of cultural harmony, while the definition of what counts as ‘historic’ and therefore worthy of legal protections actively dismantles such discourses.

One of the clearest examples of this within the Miami cityscape would be the so-called ‘shotgun shacks’ in Coconut Grove (), which, alongside Overtown, is the oldest continuously inhabited neighbourhood in the city, and which was constructed by Bahamians who migrated in the late nineteenth century to work on the construction of the railroad. These shotgun shacks are so named because, supposedly, one could shoot a bullet directly from the front door out through the back door, as they usually constitute only one or two rooms. The City of Miami’s public health officials, in fact, cited the shotgun house as the greatest cause of blight and disease, referring to it as ‘a serious threat to public health,’ and naming it as the primary drawback of an area that could best be described as ‘congested with crime and infected’ (Tscheschlok Citation1996, 460; Vought Citation2000, 58).

Nonetheless, some of the shacks remain, and are now hotly disputed as real estate developers vie for the valuable land so close to the waterfront. A local archivist who also volunteers and fundraises for the historic preservation society reported to me that ‘a lot of developers would love to get their hands on those plots. The Bahamians really built much of the Grove and the Gables but there’s not much to see of them nowadays.’ Yet just a few minutes later, she also commented

‘You would think they would be given historic status wouldn’t you? But I think part of the problem is they are very simple in style. The houses in the Gables have specific architectural features which make them worth preserving. Whereas you can find simple wood shacks like that in other parts of the country, like up in South Carolina where I grew up’ (my emphasis).

Part of this moralising dimension perhaps also relates to the sense that many older, white local residents in Miami have, as I outlined in the first section of this article, of being ‘under threat’, or at risk of being displaced amidst rapid inward waves of migration from across Latin America. The demographic fabric of Miami’s cityscape has certainly changed to a quite extraordinary degree over recent decades (Grenier and Stepick Citation1992; Portes and Stepick Citation1993; Stepick et al. Citation2003). Scholars have pointed to the structural similarities between shotgun houses in the Miami area and those in the Bahamas and West Africa as evidence of a truly diasporic architectural form in North America (Jaiyeoba Citation2021; Kahn Citation2007; Posnansky Citation2002). Rather than merely ‘simple’ or ‘vernacular’ structures that are considered unfit for modern standards of living, these shotgun shacks in the eyes of many local residents of colour are tangible traces of a multicultural history that connects Miami more to the Caribbean than to discourses of the American Confederacy. Black migrants are foundational to Miami’s hemispheric history and its longstanding connection to the Caribbean, Central and South America. Black residents of South Florida, like Michel Rolph Trouillot's description of the entire Caribbean, ‘are inescapably heterogenous … multiracial, multilingual … multicultural, [and] … inescapably historical’ (Citation1992, 21).

Conclusion

Ironically perhaps, there is also now a small but growing contingent of Miamians starting to resist historic designation. Several highly destructive hurricanes in the past decade have highlighted to the wealthy residents of waterfront properties that their homes are now increasingly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and rising sea levels. In this light, the immutability of ‘historicness’ becomes a limitation, as homeowners must apply for permission to alter buildings built for a different climate. Similar concerns are nowadays voiced in New Orleans and Charleston. In 2014, organised resistance against the county office was sparked by an attempt to declare a mid-century modern section of the town of Bay Harbor Islands (part of Miami) as an historic district. Opposition to county management of historic preservation affairs in Bay Harbor culminated in an attempted amendment to the historic preservation ordinance that would allow municipalities to opt out of county supervision. Many opponents challenged the preservation authorities’ monopoly on historic interpretation; they had differing views on what should be considered historic and how historic resources should be protected, emphasising local prerogative and community character. This move by the (wealthy) residents of the Bay Harbour area perhaps marked an initial shift, towards an acknowledgement that preservation law might be more effective when more closely aligned with the needs and character of individual communities, with such decision-making made more transparent to the communities it serves.

While communities in Overtown still struggle to receive historic recognition for their own landmarks, neighbourhoods just a few miles up the coast ironically now seek to reduce the amount of legal weight such designation can bestow. Perhaps climate change will signal a shift in focus from ‘aesthetic merit’ towards structural resilience; yet in this terrain too, communities of colour within Miami are playing ‘catch-up’. Jonah, who we met earlier in this article, was sceptical of this development:

‘you know I bet y’all gon’ get that designation and in a heartbeat now they’ll change the rules and say we gon’ strip that building down ‘cos it’s a hurricane risk. And suddenly we gotta find some historically qualified shutter system or something. I dunno, maybe we don’t need to worry about all this so much if we’ll all be underwater twenty years from now anyway … ’.

While scholars often think of ‘heritage’ as being about physical preservation, in the case presented in this article, we arguably see the opposite: ‘heritage’ belongs to the sphere of ‘culture’, which is not as easily delineated or protected through local building standards as the supposedly more ‘aesthetically quantifiable’ nature of ‘historicness’. As climate change threatens the coastal neighbourhoods all along the Florida coastline, a new ‘threat’ looms on the horizon, this time not of migration but rather a new form of ‘attrition’ posing danger to Miami’s cultural heritage. One thing remains unchanged, though: the anxiety that stokes activities of future-making, of ‘battening down the hatches’ against incoming ‘waves’ (whether migratory or tidal) is ever-present in Miami. As Pete the local history enthusiast told me: ‘it’s important we don't lose everything.’ In this, the ‘final frontier’ of America, which is now being ‘recaptured’ by the wilderness that more than a century of colonising activity has sought to ‘civilise’, the key to this act of future-making is in staking out one’s piece of ground, and memorialising it for the generation to come.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (UK). I would also like to extend my thanks to the journal’s peer reviewers, and to Kevin Yelvington and Nicholas Lackenby, for their insightful and constructive comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In many Latin American cultures, the fifteenth birthday (quinceañera) of a girl is celebrated as a sort of rite of passage towards becoming a woman, and this practice is also continued in the diaspora.

References

- Aja, Alan A. 2016. Miami’s Forgotten Cubans: Race, Racialization, and the Miami Afro-Cuban Experience. New York: Springer Press.

- Ammidown, Margot, and Ivan A. Rodriguez. 1982. From Wilderness to Metropolis: The History and Architecture of Dade County (1825–1940), 1982. Miami Dade County.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1981. “The Past as a Scarce Resource.” Man 16: 201–219. ’.

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2004. “The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition.” Culture and Public Action 59: 62–63.

- Aranda, Elizabeth M., Sallie Hughes, and Elena Sabogal, eds. 2014. Making a Life in Multiethnic Miami: Immigration and the Rise of a Global City. Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Both, William. 1998. ‘A White Migration North From Miami’. Washington Post. November 11 1998. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/meltingpot/melt1109.htm Last accessed 27/02/2024.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Certeau, Michel de. 1984. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Stephen Rendall, 102–118. Berkeley: University Of California Press.

- Chacón, Hipólito Rafael. 2001. “Creating a Mythic Past: Spanish-Style Architecture in Montana.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 51 (3): 46–59.

- City of Miami. 2016. ‘Preservation Office Historic Design Guidelines’. 2016. http://historicpreservationmiami.com/designguide/Historic%20Design%20Guidelines%20-%20FINAL.pdf. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- City of Miami. n.d. ‘About Historic Preservation’. Miami-Dade County. Accessed 21 August 2023. https://www.miamidade.gov/global/economy/historic-preservation/about.page. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- Connolly, Nathan Daniel Beau. 2006. “Colored, Caribbean, and Condemned: Miami’s Overtown District and the Cultural Expense of Progress, 1940–1970.” Caribbean Studies, 3–60.

- Connolly, Nathan Daniel Beau. 2019. A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dawdy, Shannon Lee. 2016. Patina: A Profane Archaeology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dluhy, Milan, Keith Revell, and Sidney Wong. 2002. “Creating a Positive Future for a Minority Community: Transportation and Urban Renewal Politics in Miami.” Journal of Urban Affairs 24 (1): 75–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.00115.

- Dunn, Marvin. 1997. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Fields, Dorothy Jenkins. 1998. “‘Tracing Overtown’s Vernacular Architecture’.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 23: 323–333. https://doi.org/10.2307/1504175.

- Foucault, Michel. 2007. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977–78. New York: Springer.

- Francis, Donette, and Allison Harris. 2020. “Introduction: Looking for Black Miami.” Anthurium 16: 1. https://doi.org/10.33596/anth.408.

- Geismar, Haidy. 2015. “Anthropology and Heritage Regimes.” Annual Review of Anthropology 44 (1): 71–85.

- Gosin, Monika. 2019. The Racial Politics of Division: Interethnic Struggles for Legitimacy in Multicultural Miami. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

- Grenier, Guillermo, and Alex Stepick. 1992. Miami Now! Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Change. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Hanks, Douglas, and David Smiley. 2016. ‘David Beckham Group Buys Private Land Needed for Miami Soccer Stadium’. Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article68064887.html. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- Harding, Susan, and Daniel Rosenberg. 2020. Histories of the Future. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hewison, Robert. 1987. The Heritage Industry: Britain in a Climate of Decline. Oxford, New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Hirsch, Eric, and Charles Stewart. 2005. “Introduction: Ethnographies of Historicity.” History and Anthropology 16 (3): 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757200500219289.

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jaiyeoba, Emmanuel Babatunde. 2021. “On the Search for Identity in African Architecture.” Pathways to Alternative Epistemologies in Africa, 141–163.

- Kahn, Meredith. 2007. The Shotgun House: An Architecture of Intimacy and Resistance. University of Colorado at Boulder.

- Kaufman, Ned. 2009. Place, Race, and Story: Essays on the Past and Future of Historic Preservation. New York: Routledge.

- Li, Han, and Richard J. Grant. 2022. “Climate Gentrification in Miami: A Real Climate Change-Minded Investment Practice?” Cities 131 (December): 104025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.104025.

- Lin, Jan. 2010. The Power of Urban Ethnic Places: Cultural Heritage and Community Life. Abdingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Loewen, James. 2005. Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York City: The New Press.

- Mailander Farrell, Jodie. 2021. ‘African-American History and Culture in Miami’s Overtown’. 7 May 2021. https://www.visitflorida.com/travel-ideas/articles/african-american-history-overtown-miami/. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- McCartney, Ralph. 1997. Miami-Dade “Impact of Transportation Projects on Overtown” oral history records, 1996–1998. Box 2, Folder 28. Black Archives, History and Research Foundation of South Florida.

- Meeks, Stephanie, and Kevin C. Murphy. 2016. The Past and Future City: How Historic Preservation Is Reviving America’s Communities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Merrick, George E. 1922. Coral Gables: Miami’s Riviera. Coral Gables, Fla.: G. E. Merrick. http://archive.org/details/coralgableshomes00merr. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- Merrick, George E. 1937. Planning the Greater Miami for Tomorrow. Miami: Miami Realty Board. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asc9999/id/13342/rec/1. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- Miller, Peter, and Nikolas Rose. 2008. Governing the Present: Administering Economic, Social and Personal Life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Miorelli, Camila. 2015. “Haitian Gingerbread.” Inspicio 1 (2): 8. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/inspicio/vol1/iss2/8/. Last accessed 27/02/2024.

- Mohl, Raymond A. 1987. ‘The Origins of Redlining in Miami’. https://www.housingissues.org/content/hist-redlining.pdf. Last accessed 27/02/2024.

- Mohl, Raymond A., and Mark H. Rose. 2012. “The Post-Interstate Era.” Journal of Planning History 11 (1): 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513211425786.

- Palmié, Stephan, and Charles Stewart. 2016. “Introduction.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (1): 207–236. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau6.1.014.

- Parks, Arva Moore. 2006. “George Merrick’s Coral Gables: Where Your ‘Castles in Spain’ Are Made Real.” Past Perfect Florida History.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Alex Stepick. 1993. City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami. Berkeley; London; Los Angeles: University Of California Press.

- Posnansky, Merrick. 2002. “Revelations, Roots, and Reactions- Archaeology of the African Diaspora.” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 29 (1).

- Reese, Michele. 2017. ‘Arva Moore Parks’. HistoryMiami Museum (Blog). 22 February 2017. https://historymiami.org/arva-moore-parks-2/. Last accessed 13/09/2023.

- Rivero, Nicolas. 2023. ‘Miami’s Hidden High Ground: What Sea Rise Risk Means for Some Prime Real Estate’. WUSF. 11 March 2023. https://www.wusf.org/environment/2023-03-11/miamis-hidden-high-ground-what-sea-rise-risk-means-for-some-prime-real-estate. Last accessed 27/02/2024.

- Rose, Mark H. 1990. Interstate: Express Highway Politics, 1939–1989. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- Shulman, Allan. 2021. ‘Resilient Rehab: A Guide for Historic Buildings in Miami-Dade County’. Miami-Dade County Office of Historic Preservation. https://www.miamidade.gov/planning/library/reports/resilient-rehab-report.pdf. Last accessed 13/09/2023/.

- Smalls, I. I., and C. Isaiah. 2021. ‘The 44 Percent: New Newsletter Highlights Black Community’s Role in Miami’s Founding’. Miami Herald. 17 March 2021. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article249860433.html. Last accessed 13/09/2023/.

- Stepick, Alex, Guillermo Grenier, Max Castro, and Marvin Dunn. 2003. This Land Is Our Land: Immigrants and Power in Miami. Berkeley; London; Los Angeles: University Of California Press.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1992. “The Caribbean Region: An Open Frontier in Anthropological Theory.” Annual Review of Anthropology 21 (1): 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.000315.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 2015. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Tscheschlok, Eric. 1996. “Long Time Coming: Miami’s Liberty City Riot of 1968.” The Florida Historical Quarterly 74 (4): 440–460.

- Vought, Kip. 2000. “Racial Stirrings in Colored Town: The UNIA in Miami During the 1920s.” Tequesta 60: 56–77.