Abstract

Objective: To evaluate usability of mepolizumab as a liquid drug product self-administered via a single-use prefilled autoinjector (AI) by patients with severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA), or their caregivers, in-clinic and at home.

Methods: This open-label, single-arm, Phase IIIa study (NCT03099096; GSK ID: 204959) included patients aged ≥12 years with SEA who were either receiving mepolizumab (100 mg subcutaneously [SC]) every 4 weeks (Q4W) for ≥12 weeks before screening or not receiving mepolizumab but met criteria indicative of SEA. Patients/caregivers self-administered mepolizumab (100 mg SC) via an AI Q4W for 12 weeks. The first (Week 0) and third (Week 8) doses were observed in-clinic; the second dose (Week 4) was administered unobserved at home. Primary and secondary endpoints were the proportion of patients who successfully self-administered their third and second doses, respectively (determined by investigator/site staff). Patient experience, mepolizumab trough concentrations, blood eosinophil count (BEC), and safety were also assessed.

Results: Of 159 patients/caregivers who self-administered ≥1 dose of mepolizumab, 157 completed the study. Nearly all patients successfully self-administered their third mepolizumab dose in-clinic and second dose at home (≥98% and ≥96%, respectively); this was further confirmed by mepolizumab trough concentrations/BEC. At study end, ≥88% of patients were “very” or “extremely” confident about using the AI correctly. Incidence of on-treatment drug-related adverse events (AEs) was low (3%); no fatal AEs occurred.

Conclusions: Patients/caregivers successfully self-administered mepolizumab via the AI both in-clinic and at home; no new safety concerns were identified.

Introduction

Approximately 5–10% of patients with asthma have severe disease, which is defined as asthma that requires treatment with high-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus a second controller and/or systemic corticosteroids to maintain control or that remains uncontrolled despite these treatments (Citation1). Severe asthma is a heterogeneous disease and several clinical phenotypes have been identified, one of which is severe eosinophilic asthma (SEA) (Citation1,Citation2). Patients with SEA experience recurrent exacerbations and persistent eosinophilic airway inflammation, typically driven by T2 interleukins (IL) such as IL-5 and IL-13 (Citation1,Citation2). Mepolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-5 and selectively inhibits eosinophilic inflammation (Citation3,Citation4). During its clinical development program in patients with SEA, mepolizumab was well-tolerated, reduced exacerbation rates, decreased oral glucocorticoid dependence, improved lung function, increased asthma control, and improved health-related quality of life compared with placebo (Citation5–8).

Currently, mepolizumab is approved for use as an add-on treatment for patients with SEA (100 mg subcutaneously [SC]) and for patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (300 mg SC) once every 4 weeks (Citation3,Citation4). The current approved formulation is a sterile, single-use, lyophilized formulation, which requires aseptic reconstitution in sterile water prior to SC injection by a healthcare professional (HCP) (Citation3,Citation4). However, mepolizumab liquid in a ready-to-use single-use prefilled autoinjector (AI) or safety syringe has recently been developed with the aim of allowing patients (or their caregivers) to administer the drug at home, thereby potentially helping to increase convenience.

A number of advantages to self-administered medications have been highlighted in the literature, including improved convenience for patients and HCPs, and potentially lower healthcare costs given the reduced need for clinic visits (Citation9,Citation10). The objective of this open-label, single-arm, repeat-dose, multicenter study was to evaluate the use of a single-use prefilled AI for the self-administration of mepolizumab (100 mg SC) both in-clinic and at home in patients with SEA.

Methods

Study design

This was an open-label, single-arm, repeat-dose, multicenter Phase III study of mepolizumab liquid administered SC via an AI (Supplementary Figure 1A) in patients aged ≥12 years with SEA (GSK ID: 204959; NCT03099096). Patients were enrolled across a total of 38 sites in seven countries (16 in the USA, six in Germany, five in the UK, four in Canada, three in Australia, two in Russia, and two in Sweden) from May 4, 2017 to November 30, 2017. The study consisted of a prescreening visit (Visit 0) that occurred up to 14 days prior to screening initiation (including the day of screening), a screening visit (Visit 1) that initiated a screening period of 1–4 weeks, and a 12-week treatment period (Visits 2, 3, and 4 at Weeks 0, 4, and 8) that concluded with end of study assessments 4 weeks after the last dose of mepolizumab (Week 12). Permissible visit intervals were 4 weeks ± 1 week to give investigators/patients some flexibility for making appointments. The study was approved by the appropriate regulatory and ethics committees and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2008 and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to study participation.

Patients

Eligible patients were ≥12 years of age and had a diagnosis of asthma for ≥2 years. Patients were either receiving mepolizumab (100 mg SC) every 4 weeks for ≥12 weeks prior to screening (Visit 1), or were not receiving mepolizumab treatment at screening but met the following additional criteria: a blood eosinophil count (BEC) of ≥150 cells/μL at screening or ≥300 cells/μL in the previous 12 months, regular treatment with high-dose ICS in the 12 months prior to screening (or considered as requiring treatment with high-dose ICS to mitigate the risk of exacerbations, but currently receiving a lower dose of ICS due to financial/tolerance issues), plus an additional controller medication for ≥3 months or a documented failure of an additional controller medication in the previous 12 months, and a history of ≥1 exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids (SCS) in the 12 months prior to screening. Patients had to have normal liver function before commencing study treatment. In addition, patients with prespecified concurrent medical conditions, history of alcohol/substance abuse or hypersensitivity to any component of the study medication were excluded, as were those using prohibited concomitant medications.

Treatments

Mepolizumab liquid (100 mg SC, which has been shown to have a pharmacokinetic [PK] profile that is statistically comparable to the reconstituted lyophilized formulation) (Citation11) was self-administered by the patient (or their caregiver) with an AI every 4 weeks for up to 12 weeks. If the patient chose to have their caregiver perform the injection, all doses were to be injected by the same caregiver. “Self-administration” is used throughout to describe injections administered by the patient/caregiver. Two different device labels were used in this study based on guidance provided by regulatory agencies regarding device labeling preferences: the “standard device label + pictogram (a quick reference guide summarizing key injection techniques; Supplementary Figure 1B) AI (AI with pictogram),” was used at sites in the USA, UK, and Australia, and the “standard device label AI (AI without pictogram),” was used at sites in Germany, Canada, Russia, and Sweden. The first dose of mepolizumab was self-administered under supervision in-clinic at Week 0 (Visit 2) after receiving training consisting of an introduction to the product instructions for use (IFU); the second dose at Week 4 (within 24 h of Visit 3) was self-administered unobserved at home; and the third dose at Week 8 (Visit 4) was self-administered in-clinic under supervision.

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients who were able to successfully self-administer their observed third dose in-clinic at Week 8. The secondary endpoint was the proportion of patients who were able to successfully self-administer their unobserved second dose (outside the clinic setting) at Week 4. Injection success was determined by the investigator/site staff based on observer or at-home checklists, and by visual inspection of the AI. For the second dose, injection success was determined at the next scheduled visit (Week 8). Other endpoints included proportion of patients able to successfully self-administer all three doses (at Weeks 0, 4, and 8), investigator evaluation of user/device errors, patient/caregiver assessment of device usability, and functionality assessed via a questionnaire.

Blood samples for mepolizumab plasma concentrations assessment were collected at Week 0 (pre-dose), Week 4, Week 8 (pre-dose), and at End of Study Visit/Week 12 (trough concentration [Ctrough]). A validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (assay range: 50–5,000 ng/mL) was used to determine mepolizumab plasma concentrations. BECs, for determination of ratio to baseline at each time point, were measured at screening, Week 0 (pre-dose), Week 4, Week 8 (pre-dose), and at End of Study Visit/Week 12 as part of standard hematological assessment.

Incidence of asthma exacerbation, defined as worsening of asthma requiring the use of SCS for ≥3 consecutive days and/or hospitalization and/or emergency department visit, was recorded. Safety endpoints included incidence and frequency of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs) including systemic reactions and injection site reactions, level of self-reported pain immediately, 1 h and 24 h after each injection, and incidence of immunogenicity.

Sample size and statistical analysis

No formal sample size calculations were performed. Based on the assumption of a 30% screen failure rate and a 5% withdrawal rate, approximately 225 patients were to be screened with the aim of 150 patients completing the study (100 patients using the AI with pictogram and 50 patients using the AI without pictogram).

Three populations were defined for analysis as follows (i) all patients (AP) enrolled population comprising all patients for whom a record existed in the database (population used to summarize reasons for screen failures); (ii) all patients treated (APT) population comprising patients/caregivers who attempted ≥1 self-administration of mepolizumab via an AI (population used to assess all endpoints relating to AI use, asthma exacerbations, immunogenicity, safety, and PK); (iii) pharmacodynamic [PD] population comprising patients in the APT population who had a baseline PD measurement and ≥1 post-baseline PD measurement.

All analyses to evaluate the AI were reported separately for the group of patients using the AI with pictogram and the group of patients using the AI without pictogram. No hypothesis testing was planned or performed. The number and proportion of patients able to successfully self-administer their doses of mepolizumab using the AI with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was reported. The denominator for the percentage was the number of patients/caregivers attempting an injection at the respective time point, and CIs were generated using the Exact (Clopper Pearson) method for binomial proportions. Device usability/functionality questionnaires were summarized descriptively. A post hoc analysis summarizing device usability/functionality questionnaires for the subset of patients who injected themselves correctly at Week 8 was also performed. Mepolizumab plasma concentrations were summarized descriptively by previous mepolizumab use. BECs were log transformed, and absolute and ratio to baseline values were summarized descriptively by previous mepolizumab use. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient population

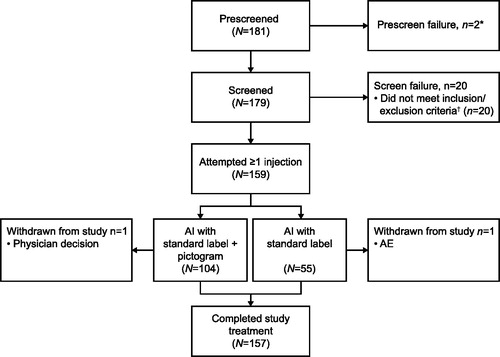

Of 181 patients screened, 159 attempted to self-administer at least one dose of study treatment and were included in the APT population (). Of these, 104 (65%) used the AI with pictogram and 55 (35%) used the AI without pictogram. All 159 patients had at least one sample collected and analyzed for PK assessment and all but one patient (>99%) had a baseline and at least one post-dose sample collected for PD assessment (PD population). In total 157 (99%) patients completed the study ().

Figure 1. Summary of patient disposition (AP population). *The electronic case report form did not allow a reason for prescreen failure to be defined. †Including protocol-defined continuation criteria. Prescreen failure includes any patient who was assigned a patient number but did not complete any screening procedures. Screen failure includes any patient who completed at least one screening procedure, but the patient/caregiver did not attempt to self-administer a dose of mepolizumab via an AI. Study completion includes any patient who completed all assessments at the end of study visit. Two patients were withdrawn from the study after self-administering their first dose of mepolizumab; one patient owing to serious AEs relating to a traffic accident and one patient owing to physician decision (failure to comply with study procedures and unreliability). AE: adverse event; AI: autoinjector; AP: all patients enrolled.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in . Most patients (122/159; 77%) were in the 18–64 years age category (). The mean asthma duration was 23.3 years and approximately half (84/159; 53%) of patients were receiving mepolizumab treatment at baseline (). Almost three-quarters of patients (73%) in this study had no prior experience with self-injecting medication. Of the 43 patients who did have prior experience, 60% had previously used a prefilled safety syringe, 35% had used an AI, and 14% had used a vial and syringe. Most patients chose to self-administer the first injection themselves, as opposed to choosing a caregiver to administer the drug (93% and 100% for AI with and without pictogram, respectively).

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics (APT population).

Primary and secondary endpoints

At Week 8, 102/103 (99%) patients using the AI with pictogram and 53/54 (98%) patients using the AI without pictogram successfully self-administered their third mepolizumab dose in-clinic (). Both unsuccessful injections at Week 8 were deemed so because the patient injected into the upper arm rather than the thigh or abdomen. Per protocol, the upper arm injection site was only allowed when a caregiver administered the injection and was considered an injection failure even though the patient had otherwise successfully administered their mepolizumab dose.

Table 2. Summary of injection success including observer and at-home checklists (APT population).

All but two patients using the AI with pictogram (n = 101; 98%) and all but two patients using the AI without pictogram (n = 52; 96%) were reported by the investigator/site staff to have successfully administered their unobserved at-home second dose of mepolizumab at Week 4 (). Reasons for unsuccessful injections at Week 4 in the AI with pictogram group were a user error, described as the patient not engaging the device prior to the medication leaving the AI resulting in the medication dispensing on the counter (subsequent inspection of the AI concluded that no mechanical device failure had occurred) and incorrect injection site (upper arm). In the AI without pictogram group, the two unsuccessful injections resulted from the AI being pulled away before the end of the injection.

Other injection success endpoints

In the AI with pictogram group all but five patients (95%) attempting an injection were reported by the investigator/site staff to have successfully self-administered all three doses of mepolizumab (at Weeks 0, 4, and 8) () and no patient failed all three injections. In the AI without pictogram group all but six patients (89%) attempting an injection were reported by the investigator/site staff to have successfully self-administered all three doses of mepolizumab (at Weeks 0, 4, and 8) () and no patient failed all three injections.

User/device errors

There were no device failures that affected injection success. For all injections, each injection step was completed “easily” without repeated reference to the IFU by ≥89% of patients/caregivers using either the AI with or without pictogram. Results from the observer checklist at Week 0 showed that ≤11% of patients using either the AI with or without pictogram reported having “some difficulty” in completing all the IFU steps. Results from the at-home checklist (Week 4) and observer checklist (Week 8) showed that ≤5% of patients using either the AI with or without pictogram reported having “some difficulty” in completing all the IFU steps (). None of these patients/caregivers continued to have difficulty with the same steps during subsequent self-administrations.

Device usability and functionality

At study completion, some patients/caregivers (8% using the AI with pictogram and 4% using the AI without pictogram) expressed that they had felt “very” or “extremely” anxious self-administering mepolizumab at home (). However, 96% of patients using the AI with pictogram and 88% of patients using the AI without pictogram were “very” or “extremely” confident about their ability to use the AI in the correct way when they were on their own. In addition, 92% of patients using the AI with pictogram and 86% of patients using the AI without pictogram found mepolizumab in an AI “very” or “extremely” easy to self-administer at home; of those who injected themselves correctly at Week 8 using the AI with pictogram, 92% found the AI “very” or “extremely” easy to use (). At study completion slightly more patients stated that they preferred the upper thigh as an injection site rather than the abdomen (53% vs 47% for AI with pictogram; 55% vs 45% for AI without pictogram) (). Almost all patients using the AI with pictogram and the AI without pictogram indicated they would recommend this device to other patients with asthma (98% and 100%, respectively). Patients who were receiving treatment with mepolizumab at screening were asked to compare their experience of self-administration using an AI to administration by an HCP prior to entering the study. In both the AI with pictogram and the AI without pictogram groups most patients (45/47 and 24/25, respectively) expressed a preference for receiving mepolizumab via an AI at home rather than administered by an HCP.

Table 3. Patient/caregiver perception of AI usability (APT population).

PK

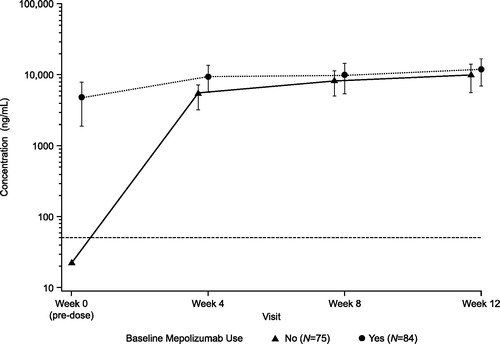

In patients receiving mepolizumab at screening, mean mepolizumab plasma Ctrough remained similar during the study treatment period and was overall consistent with the baseline value. In patients who were not receiving mepolizumab at screening, mean mepolizumab plasma Ctrough increased following each self-administration, and at the End of Study Visit/Week 12 the mean Ctrough was similar to that observed in patients already receiving mepolizumab at screening ().

PD

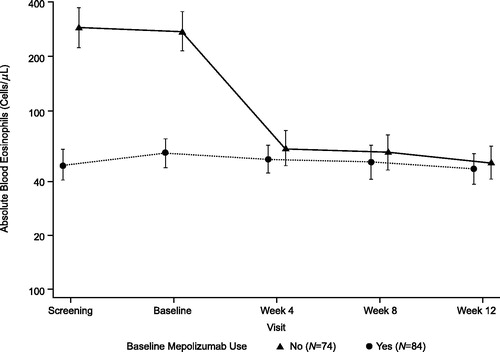

At study initiation, the geometric mean baseline BEC was lower (57 cells/μL [95% CI: 48, 69]) in patients who were receiving mepolizumab at screening compared with those who were not (275 cells/μL [95% CI: 216, 351]). However, geometric mean BECs from Week 4 onwards were similar between the two groups during the study treatment period (). By Week 12, geometric mean BECs were reduced to 51 cells/μL in patients not receiving mepolizumab at screening and 47 cells/μL in patients receiving mepolizumab at screening.

Asthma exacerbations

During the 12-week treatment period, 22 (14%) patients experienced ≥1 asthma exacerbation and were subsequently treated with SCS; none led to discontinuation of study treatment. Of the 22 patients who experienced ≥1 asthma exacerbation, 10 were receiving mepolizumab treatment at screening.

Safety

The overall incidence of on-treatment AEs was low (56/159; 35%), and few patients were considered by the investigators to have drug-related AEs (5/159; 3%; ). Drug-related AEs included local injection site reactions (n = 4), chills (n = 1), fatigue (n = 1), dry mouth (n = 1), and headache (n = 1); none resulted in discontinuation of study treatment or withdrawal from the study. The most common on-treatment AEs were nasopharyngitis (9/159; 6%) and headache (8/159; 5%). There were nine on-treatment SAEs reported for four patients (asthma, chest discomfort, and alveolitis allergic were each reported for one patient, all of which resolved) and six SAEs related to a traffic accident were reported for one other patient. All SAEs were considered unrelated to mepolizumab by the investigator and none were fatal. The traffic accident and accompanying SAEs resulted in discontinuation of study treatment and withdrawal of this patient from the study. One pretreatment SAE of asthma exacerbation was reported for one patient. This event did not meet the protocol-specified criteria for reporting as a pretreatment SAE. Incidence of AEs of special interest is shown in .

Table 4. Adverse events (APT population).

The proportion of patients reporting any pain (visual analog scale [VAS] score >0) immediately following injection was 60% (85/141) at Week 0, 57% (73/129) at Week 4, and 43% (65/150) at Week 8 (). The intensity of the pain was low, with the median VAS score at these time points ranging from 0.0 to 3.0 on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst possible pain). At 1 h and 24 h following each of the injections, the proportion of patients experiencing pain decreased, as did the relative degree of pain reported, with median VAS scores of 0.0 1 h and 24 h after all three injections (). The most commonly reported description of pain immediately after each dose was sharp/stinging (53%, 45%, and 57% at Weeks 0, 4, and 8, respectively). At 1 h and 24 h after each injection the most commonly reported descriptions of pain, respectively, were dull/aching (ranging from 39% to 56%) and “other” (ranging from 39% to 50%), which included any pain that was not described as sharp/stinging, dull/aching or burning.

Table 5. Injection pain summary (APT population).

Immunogenicity was assessed at baseline and at the End of Study Visit/Week 12. The number of patients with detectable anti-drug antibodies post-baseline was low (two patients; 1%). No patients developed neutralizing antibodies over the 12-week treatment period.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the safety and usability of an AI device to deliver mepolizumab (100 mg) SC in patients with SEA. Nearly all patients successfully self-administered their third mepolizumab dose in-clinic and second dose at home (≥98% and ≥96%, respectively) as reported by the investigator/site staff, demonstrating the usability of the AI device to administer mepolizumab both with and without supervision, and either with or without a pictogram in the label. An associated study conducted in 56 patients, which assessed the self-administration of mepolizumab using a single-use prefilled syringe (PFS), demonstrated comparable results, whereby all 55 patients/caregivers who completed the second/third injections were able to successfully self-administer their second and third doses of mepolizumab, at home and in-clinic, respectively (Citation12). These studies also showed that a single training session and the IFU were sufficient for patients/caregivers to acquire the skills necessary to successfully self-administer mepolizumab, either with a PFS or with an AI.

The AI provides a simple method of self-administration and shrouds the needle from the patients’ view, characteristics that are likely to have contributed to the positive feedback received from patients regarding this device. In addition, only 7/103 (7%) patients using the AI with pictogram and no patients using the AI without pictogram elected to have a caregiver administer the first injection, in contrast to 7/56 (13%) patients in the PFS study (Citation12), suggesting that the AI might be more appealing than the PFS for self-administration. The majority of patients reported that each injection step was completed “easily” without the need for repeated reference to the IFU and by the end of the study treatment period, almost all patients expressed confidence in their ability to self-administer mepolizumab using the AI unsupervised. Furthermore, ≥98% of patients indicated that they would recommend the device to other patients with asthma. Together, these findings suggest self-administration is a viable treatment option that could be offered as an alternative to in-clinic administration for those patients who may prefer and can administer medication in the convenience of their home. Satisfaction with self-administration at home has been demonstrated in other therapeutic areas including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, primary immunodeficiency disease, oncology, and multiple sclerosis (Citation13–18). Given the reduced need to attend the clinic, self-administration of mepolizumab in a home setting may also reduce the overall use of healthcare resources and improve adherence.

Overall, the incidence of on-treatment AEs was low, with the majority of AEs considered by the investigator as unrelated to the study treatment. In this study, the number of patients (N = 159) was small and the treatment period was relatively short (12 weeks), hence the ability to detect safety concerns was limited. However, it is worth noting that changes to the manufacturing process for the liquid mepolizumab formulation compared with the reconstituted lyophilized formulation were minimized. Furthermore, the liquid mepolizumab formulation has been shown to have a PK profile that is statistically comparable to the current reconstituted lyophilized formulation (Citation11). Therefore, the likelihood of clinically significant differences in the systemic exposure, efficacy, safety and/or immunogenicity of mepolizumab delivered via the AI as compared with the current reconstituted lyophilized formulation is considered to be low. The safety profile reported here is similar to that observed in previous trials of patients with SEA using the current reconstituted lyophilized formulation (Citation5–8) and is also broadly consistent with the associated PFS study (Citation12).

Furthermore, also in line with the PFS study, the incidence of pain associated with injection was reported as being of low intensity and decreased within 1 h of the injection and with each subsequent injection. This trend for a decrease in pain scores with increasing experience with injections has been previously reported with AI use in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (Citation15). This effect may be due to the patients change in expectations of pain, and/or the patient becoming more tolerant to pain with repeated self-injections.

In this study, 14% of patients experienced ≥1 asthma exacerbation requiring SCS treatment, approximately half of whom were receiving mepolizumab at screening. This is in line with the related PFS study, in which 13% of patients experienced an asthma exacerbation (Citation12). Individual PK and PD profiles observed in this study corroborate the successful self-administration of mepolizumab via an AI. The values we observed are consistent with those observed in a previous randomized placebo-controlled mepolizumab trial, where BECs were reduced to approximately 50 cells/μL (Citation6).

One limitation of this study was the small proportion of adolescent (7%) and older patients (≥65 years, 16%) in the study population. Further information on the usability of the AI device in these populations would be beneficial; however, other studies have shown that high injection success rates were achieved with AI devices across a variety of participant demographics and disease characteristics (Citation19–21). A further study limitation was the potential for patient selection bias given that only patients who were willing to self-administer mepolizumab at home participated. This selection bias may mean the data are not truly representative of the entire population eligible for mepolizumab, although it may be consistent with the population of patients who are likely to be willing to self-administer mepolizumab in the future. Therefore, for those patients who are open to the idea of self-administration, the study provides valuable information on the success of mepolizumab self-administration over a 12-week period as well as the patients’ perspectives on the challenges and advantages of this method of administration.

Conclusion

The results from this study demonstrate that almost all patients/caregivers were able to successfully self-administer mepolizumab (100 mg SC) using an AI, both in-clinic and at home. Mepolizumab delivered via an AI was well-tolerated in patients with SEA and had a similar safety profile to the current reconstituted lyophilized formulation. Taken together, these results suggest that the self-administration of mepolizumab via an AI is a viable alternative to the reconstituted lyophilized formulation delivered in-clinic and offers patients the convenience of being able to self-inject at home.

Declaration of interest

RF, JHB, IP, and EB are employees of GSK and hold stocks/shares. DB received grant/research/clinical trial support from GSK, Teva, AstraZeneca, Pearl, Novartis, Genentech, Lupin, Merck, Mylan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Amgen, Aimmune, Menlo, Shire, Biocryst and consulted/participated in advisory boards for GSK, ALK America, Gerson-Lehman, Guidepoint Global. IDP has received fees for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Aerocrine, Almirall, Novartis, Teva, Chiesi, and GSK; fees for organizing educational events from AstraZeneca and Teva, honoraria for attending advisory panels with Genentech, Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Novartis, Teva, Sanofi, Circassia, Chiesi, Almirall, and Knopp; sponsorship to attend international scientific meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca, Teva, and Chiesi; a research grant from National Institute for Health Research. KRC has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GSK, Grifols, Kamada, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi Regeneron; has undertaken research funded by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GSK, Grifols, Kamada, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi; has participated in continuing medical education activities sponsored in whole or in part by AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Grifols, Novartis, and Teva. KRC is participating in research funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and holds the GSK-CIHR Research Chair in Respiratory Health Care Delivery at the University Health Network, Toronto, Canada.

Author’s contributions

RF, JHB, IP, and EB were involved in the conception or design of the work; DB, IDP, and KRC were involved in the acquisition of data; and all authors participated in data analysis and interpretation of the work. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (199.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and caregivers who took part in this study and Will Williams and Rosalida Leone who were the Study Managers. Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft from the study report, assembling tables and figures, collating authors’ comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Kerry Knight, PhD, at Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, and was funded by GSK.

Data sharing statement

Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343–73. doi:10.1183/09031936.00202013.

- Wenzel S. Severe asthma: from characteristics to phenotypes to endotypes. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:650–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03929.x.

- GlaxoSmithKline. Mepolizumab (NUCALA) US prescribing information. 2015 [accessed 2018 Dec 4]. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125526s004lbl.pdf.

- GlaxoSmithKline UK. Mepolizumab (NUCALA) EU summary of product characteristics [accessed 2018 Dec 4]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/product-information/nucala-epar-product-information_en.pdf.

- Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, Bleecker ER, Buhl R, Keene ON, Ortega H, Chanez P. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, Humbert M, Katz LE, Keene ON, Yancey SW, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1198–207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403290.

- Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, Prazma CM, Keene ON, Yancey SW, Ortega HG, Pavord ID, for the SIRIUS Investigators. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1189–97. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403291.

- Chupp GL, Bradford ES, Albers FC, Bratton DJ, Wang-Jairaj J, Nelsen LM, Trevor JL, Magnan A, Ten Brinke A. Efficacy of mepolizumab add-on therapy on health-related quality of life and markers of asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma (MUSCA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:390–400. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30125-X.

- Kivitz A, Cohen S, Dowd JE, Edwards W, Thakker S, Wellborne FR, Renz CL, Segurado OG. Clinical assessment of pain, tolerability, and preference of an autoinjection pen versus a prefilled syringe for patient self-administration of the fully human, monoclonal antibody adalimumab: the TOUCH trial. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1619–29. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.006.

- Noone J, Blanchette CM. The value of self-medication: summary of existing evidence. J Med Econ. 2018;21:201–11. doi:10.1080/13696998.2017.1390473.

- Shabbir S, Pouliquen I, Bentley JH, Bradford ES, Kaisermann MC, Albayaty M. The pharmacokinetics and relative bioavailability of mepolizumab 100 mg liquid formulation administered subcutaneously to healthy participants: a randomized trial. American Thoracic Society International Conference; 2019 May; Dallas, TX, USA.

- Bel EH, Bernstein DI, Bjermer L, Follows R, Bentley JH, Pouliquen I, Bradford E. Usability of mepolizumab single-use prefilled syringe for patient self-administration. J Asthma. 2019:24:1–10. doi:10.1080/02770903.2019.1604745.

- Huynh TK, Ostergaard A, Egsmose C, Madsen OR. Preferences of patients and health professionals for route and frequency of administration of biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:93–9. doi:10.2147/PPA.S55156.

- Keininger D, Coteur G. Assessment of self-injection experience in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: psychometric validation of the Self-Injection Assessment Questionnaire (SIAQ). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:2. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-2.

- Sheikh SZ, Hammer AE, Fox NL, Groark J, Struemper H, Roth D, Gordon D. Evaluation of a novel autoinjector for subcutaneous self-administration of belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;54:914–22. doi:10.5414/CP202623.

- Nicolay U, Kiessling P, Berger M, Gupta S, Yel L, Roifman CM, Gardulf A, Eichmann F, Haag S, Massion C, et al. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in North American patients with primary immunedeficiency diseases receiving subcutaneous IgG self-infusions at home. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:65–72. doi:10.1007/s10875-006-8905-x.

- Tjalma W, Huizing MT, Papadimitriou K. The smooth and bumpy road of trastuzumab administration: from intravenous (IV) in a hospital to subcutaneous (SC) at home. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:51–5.

- Hupperts R, Becker V, Friedrich J, Gobbi C, Salgado AV, Sperling B, You X. Multiple sclerosis patients treated with intramuscular IFN-beta-1a autoinjector in a real-world setting: prospective evaluation of treatment persistence, adherence, quality of life and satisfaction. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2015;12:15–25. doi:10.1517/17425247.2015.989209.

- Freundlich B, Kivitz A, Jaffe JS. Nearly pain-free self-administration of subcutaneous methotrexate with an autoinjector: results of a phase 2 clinical trial in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have functional limitations. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20:256–60. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000117.

- Schwarzenbach F, Dao Trong M, Grange L, Laurent PE, Abry H, Cotten J, Granger C. Results of a human factors experiment of the usability and patient acceptance of a new autoinjector in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:199–209. doi:10.2147/PPA.S50583.

- Lange J, Richard P, Bradley N. Usability of a new disposable autoinjector platform device: results of a formative study conducted with a broad user population. Med Devices (Auckl). 2015;8:255–64. doi:10.2147/MDER.S85938.