Abstract

Objective: Few studies have examined factors affecting the high frequency of hospitalization for pediatric asthma. This study identifies individual and environmental characteristics of children with asthma from a low-income community with a high number of hospitalizations.

Methods: The study population included 902 children admitted at least once to a children’s hospital in South Texas because of asthma from 2010 to 2016. The population was divided into three groups by utilization frequency (high: ≥4 times, medium: 2–3 times, or low: 1 time). Individual-level factors at index admission and environmental factors were included for the analysis. Unadjusted and adjusted multivariate ordered logistic regression models were applied to identify significant characteristics of high hospital utilizers.

Results: The high utilization group comprised 2.4% of total patients and accounted for substantial hospital resource utilization: 10.8% of all admissions and 13.5% of days stayed in the hospital. Patients in the high utilization group showed longer length of stay (LOS) and shorter time between admissions on average than the other two groups. The multivariate ordered logistic regression models revealed that age of 5–11 years (OR = 0.57, 95%CI = 0.35–0.93), longer LOS (2 days: OR = 1.80, 95%CI = 1.15–2.84; ≥3 days: OR = 3.38, 95%CI = 2.10–5.46), warm season at index admission (OR = 1.49, 95%CI = 1.01–2.20), and higher average ozone level in children’s residential neighborhoods (OR = 1.78, 95%CI = 1.01–3.14) were significantly associated with a higher number of asthma hospitalizations.

Conclusions: The findings suggest the importance of monitoring high hospital utilizers and establishing strategies for such patients based on their characteristics to reduce repeated hospitalizations and to increase optimal use of hospital resources.

Introduction

Preventable hospital readmissions are an important indicator of healthcare quality as high readmission rates can indicate sub-optimal care during a hospital stay and post discharge (Citation1–3). Asthma-related readmissions are also one of the most widely used and accepted outcome measurements of asthma exacerbations, asthma control, and care quality (Citation4–6). These rehospitalizations are prioritized in the United States (U.S.) given that hospital readmissions increase healthcare costs and negatively affects quality of life for both children and their parents/caregivers (Citation7,Citation8). Many readmissions are considered preventable with effective coordination of services and transitional care (Citation9,Citation10), so reducing preventable hospital readmissions is essential to enhance quality of care and decrease financial healthcare burdens (Citation11). By one estimate, preventing hospital readmissions could reduce U.S. healthcare costs by over $25 billion annually (Citation12).

Previous studies support that air pollution is a significant contributing factor for pediatric asthma readmissions (Citation13,Citation14). Specifically, outdoor air pollution was significantly associated with hospital readmissions among children with asthma, specifically traffic-related air pollution (Citation13,Citation15) and residential proximity to major roads (Citation16,Citation17). In addition, a growing body of literature also recognizes the significance of area-based socioeconomic deprivation on hospital-related health outcomes for asthma, such as hospitalization and emergency department (ED) visits (Citation18), in-hospital mortality (Citation19), length of stay (LOS) and costs (Citation20), and readmission rates (Citation20–22). Higher levels of area-based deprivation in neighborhoods where children live was also specifically associated with increased risk of hospital readmissions for pediatric asthma (Citation20,Citation22,Citation23); air pollution also presented as a modifying effect for asthma-related pediatric ED visits in Atlanta (Citation24).

These studies only focused on a single readmission after the index hospitalization. Other investigations defined multiple admissions as at least one readmission (Citation25–27). However, few studies have identified the characteristics of patients with a high frequency of hospitalizations. For example, a retrospective cohort study based on 37 U.S. children’s hospitals revealed that age, race/ethnicity, and use of public insurance were important characteristics associated with the highest number of readmissions (Citation28). Considering the potential differences that may exist in asthma severity, preventive care access, or air pollutant exposure among children who have been hospitalized once or multiple times (Citation29), it would be important to differentiate patients with single versus multiple readmissions and assess distinct characteristics of the highly repeated hospital utilizers. Identifying those children at an early stage would allow hospitals to use their resources more effectively and reduce acute health service utilization of children (Citation30). Therefore, this study examines individual-level and environmental characteristics of pediatric asthma patients with the highest frequency of hospitalizations in South Texas.

Materials and methods

Study population and data source

This hospital-based retrospective study pooled data over 7 years to identify high utilizers of hospital services among pediatric asthma patients and examine their individual-level and environmental characteristics. The study included children aged 5–18 years old, living in South Texas, who were admitted at least once to the Driscoll Children's Hospital in South Texas with a primary diagnosis of asthma between 2010 and 2016. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Texas A&M University and Driscoll Children's Hospital.

Data were gathered from multiple sources. First, hospitalization data for children admitted to the hospital due to asthma (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, 493-493.92 or ICD, 10th Revision, J45.21-J45.909) were collected through the hospital’s electronic database. All records included age, gender, ethnicity, type of insurance, use of medication, admission date, discharge date, and patients’ residential census tract information. The research team collected outdoor air pollution data from the Environmental Public Health Tracking Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Citation31). The daily average predictions modeled for two types of air pollutants, Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5) and ozone concentrations, were estimated by using the Downscaler model of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency at the census tract level (Citation32). The data available were limited to those between 2001 and 2014, so we calculated the average values during 2010–2014 in order to obtain the overall air pollution levels in each census tract.

We gathered social deprivation data from the social vulnerability index (SVI) created by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry of the CDC (Citation33). This percentile rank index was developed to determine social vulnerability of each community in the census tract level by using fifteen social factors based on the U.S. census data, including poverty, education transportation, minority status, and household composition (Citation34). The 15 social factors are presented in . Given data availability, the social vulnerability variable was created as an average of SVI values for 2010, 2014, and 2016 in census tract level to cover the study period. We linked the data of outdoor air pollution and SVI to the hospitalization data by using census tract information.

Table A1. List of 15 factors for social vulnerability index

Measurement

In this study, asthma hospitalization was defined as any hospital admission with a primary diagnosis of asthma. A unique medical record number was used to track each patient’s hospitalizations during the study period. The dependent variable representing hospital utilization groups was determined based on the total number of hospitalizations between 2010 and 2016 for pediatric patients with asthma who were admitted to the hospital. This ordinal variable was divided into three groups given its distribution: (i) low utilization group (hospitalized once with no readmissions), (ii) medium utilization group (hospitalized two or three times), and (iii) high utilization group (hospitalized four times or more). Patients in the high utilization group represented the 97.5th percentile in the distribution of hospitalizations among the study population. Hospital resource utilization, including the number of admissions, the number of days spent in the hospital, and time between hospitalizations (days), was accumulated for each patient during the entire study period and calculated to compare among the three hospital utilization groups. We divided the time between hospitalizations for patients who had at least one readmission into four categories: (i) 1–30 days, (ii) 31–90 days, (iii) 91–365 days, or (iv) 366 days or longer.

The independent variables contained various individual-level and environmental factors, all of which may affect hospital readmission for pediatric asthma patients to a certain degree. First, individual-level characteristics included age (5–11 years old or 12–18 years old), gender (male or female), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), type of insurance (public: Medicaid or private/self-pay), use of medication (yes or no), LOS (1 day, 2 days, or ≥3 days), season (warm: May–October or cold: November–April) and year. LOS was calculated as the difference in days between the admission date and the discharge date. LOS for a patient admitted and discharged on the same day was recorded as one day. The information gathered at the initial admission was used in this study.

Environmental characteristics for this study included two types of air pollutants (PM2.5 and ozone levels) and social deprivation in neighborhoods where children live. We measured these variables based on each patient’s census tract information. PM2.5 and ozone concentrations were divided into four categories as quartiles: quartile 1 (the lowest) to quartile 4 (the highest) (Citation35). Social deprivation factor was estimated by calculating the average of SVI data of years 2010, 2014, and 2016 to cover the years of 2010 to 2016 in each census tract. The range of this index is between 0 (least vulnerable) and 1 (most vulnerable). We also categorized this variable into four categories by quartile from quartile 1 (the lowest) to quartile 4 (the highest) for outdoor air pollution.

Statistical analysis

Hospital resource utilization of asthma patients during 2010–2016 was compared among the hospital utilization groups by calculating median and interquartile range (IQR) since the data was not normally distributed. We calculated the baseline characteristics of the study population to estimate the median and IQR for continuous variables, or percentages of categorical variables in total and by hospital utilization groups. The Kruskal–Wallis H tests for continuous variables and the chi-square tests for categorical variables were performed to compare the hospital resource utilization and characteristics among three groups of hospital utilizers: low, medium, and high groups. We compared time between hospitalizations only in medium and high utilization groups. Pearson correlation was used to test if air pollution and SVI was highly correlated.

Bivariate and multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify significant factors that affect a high number of hospitalizations since the dependent variable was categorical and ordered. We developed three different regression models: model 1 (unadjusted model), model 2 (adjusted model with only individual-level factors), and model 3 (adjusted model with individual-level and environmental factors). To evaluate the robustness of the findings, we performed the multivariate regression analysis with each air pollutant, separately. The results were represented as the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14 version (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p values <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

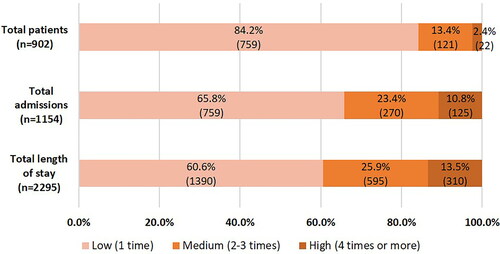

A total of 902 patients were admitted to the hospital at least once during 2010–2016 in South Texas. Among the study population, 121 patients (13.4%) experienced 2–3 hospitalizations and 22 patients (2.4%) had ≥4 hospitalizations (). There were 1154 hospitalizations with 2295 days spent in the hospital between 2010 and 2016 in total. The high utilization group consisted of 2.4% of total patients and accounted for substantial hospital resource utilization: 10.8% (125/1154) of total admission and 13.5% (310/2295) of total number of hospital stays ().

Figure 1. Hospital resource utilization of pediatric patients with asthma admitted to Driscoll Children’s hospital during 2010–2016.

Hospital resource utilization of pediatric asthma hospitalizations were compared among low, medium, and high utilization groups (). Patients in the high group stayed much longer (12-day LOS) than the medium (4 days) and low (1 day) groups when they were hospitalized (p < 0.001). When comparing median days between hospitalizations, the high group showed significantly shorter time in between hospitalizations than the medium group (169 vs. 331 days; p < 0.001). Furthermore, we found that only 9.7% of readmissions in the high group occurred within 30 days, and that most of the total readmissions (77.8% for all patients and 66.0% for the high group) occurred 90 or more days after previous admission.

Table 1. Comparison of hospital resource utilization among low, medium, and high groups in pediatric asthma hospitalizations.

Descriptive statistics of the study population at index admission were presented across the three groups (). Most of the study cohort (76.1%) were children aged 5–11 years old and about three quarters were Hispanic (75.2%). Over two-third (68.4%) had public insurance and about 20% remained in the hospital for 3 days or longer at index admission. When comparing characteristics among groups, only the differences in LOS and admission year at initial hospitalization were statistically significant. Specifically, the percentage of hospital stays for 3 days or longer was significantly higher in the high utilization group when compared with the medium and low groups (p < 0.001). In particular, the high utilization group showed twice the percentage (36.4% vs. 17.3%; p < 0.001) as the low utilization group for LOS ≥3 days. None of the environmental factors showed significant differences among groups although percentages of the highest ozone level group (quartile 4) were larger in the high utilization group (31.8%) than the medium (19.8%) and low groups (26.8%; p = 0.052). Moreover, Pearson correlation tests between air pollutants and SVI showed that they were not highly correlated (0.21–0.43; p < 0.001; ).

Table A2. Pearson correlation coefficients between ambient air pollutants and social vulnerability index.

Table 2. Comparison of patient and environmental characteristics among hospital utilization groups.

The results of bivariate and multivariate ordered logistic regression analyses were shown to identify characteristics of the high utilization group (). In the unadjusted model, ages 5–11 years old and longer LOS at index admission were significantly associated with a higher frequency of hospitalization (age: p = 0.031; LOS: p = 0.005 [2 days], p < 0.001 [≥3 days]). The multivariate analysis, controlling for only individual-level factors, showed that age, LOS, and season were significant characteristics for high hospital utilizers. That is, children aged 5–11 years old (p = 0.020), who stayed longer in the hospital (2 days: p = 0.011; ≥3 days: p < 0.001), and who were admitted during the warm season (p = 0.034) at index admission were significantly more likely to have a higher number of hospitalizations.

Table 3. Results of bivariate and multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis among hospital utilization groups.

In the multivariate model controlling for individual-level and environmental factors, the results for individual-level factors were consistently represented as the previous adjusted model (age of 5–11 years: p = 0.025; longer LOS: p = 0.011 [2 days], p < 0.001 [≥3 days]; warm season: p = 0.042). We also found that children living in areas with ozone level of quartile 2 were more likely to be admitted to the hospital than those living in areas with the lowest ozone level (quartile 1; p = 0.045). The multivariate analysis with each pollutant (single-pollutant models) also showed consistent results that age, LOS, season, and ozone level were important factors for higher number of hospitalizations for pediatric asthma ().

Table A3. Results of multivariate ordered logistic regression analysis for each pollutant.

Discussion

This study examined the individual-level and environmental characteristics of pediatric patients who had the highest number of asthma hospitalizations in a children’s hospital in South Texas. The relatively small number of patients within the high utilization group (2.4% of the total patients) accounted for significant hospital resource utilization: 10.8% of total admissions and 13.5% of total time stayed in the hospital. Patients in the high utilization group also showed longer LOS and shorter time gap between admissions on average when compared to the low and medium utilization groups. Our findings are consistent with a previous study that found about 3% of the total patients (the group with the highest frequency of readmissions) accounted for about 19% of total hospitalization and about 23% of total LOS (Citation28). Patients readmitted most often are also readmitted sooner and stay longer. Thus, identifying the high utilization group and establishing specific strategies for this group is essential to use hospital resources efficiently and reduce healthcare costs effectively. Given high costs of asthma hospitalizations in particular, by one well-surveyed estimate over $5000 per patient (Citation36), preventing hospitalizations especially of the high utilization group would contribute to saving considerable healthcare costs.

Timing is also a factor. We found that the average time between admissions was 274 days for all patients who experienced at least two episodes of hospitalization, and 169 days for those with hospitalizations of four times or more. Fewer than 10% of readmissions in the high group occurred within 30 days; most readmissions (77.8% for all patients and 66.0% for the high group) had 90-day or longer readmissions. If hospitals only focus on the traditional 30-day readmissions, most patients with repeated hospitalizations, especially patients with the highest number of admissions, might be under-recognized in receiving necessary transitional care. Therefore, hospitals should monitor the number of hospitalizations for individual patients and establish their readmission reduction initiatives based on distribution of hospitalizations and the resource utilization of patients with the higher number of admissions.

To that end, we observed three individual-level characteristics of patients with the highest number of asthma admissions: age, hospital LOS, and season at index admission. This study showed that children aged 5–11 years were more likely to have a higher number of hospitalizations than those aged 12–18 years. Previous studies exploring asthma readmission by age group showed mixed results. Most studies reported children aged <5 years or 10–18 years were more likely to be readmitted to a hospital (Citation23,Citation37–39). Yet, these studies had different reference groups, and we could not find any study that compared the same age groups as this current study. Moreover, we found that initial admission during the warm season was a significant characteristic of the high utilization group. This finding corroborates previous research that found higher readmission rates for children admitted in the summer or fall versus winter (Citation23). The most pronounced finding was that longer LOS at index admission was significantly associated with a higher frequency of hospitalizations. This result supports those observed in earlier studies. A study in Rhode Island revealed that patients with LOS of ≥3 days at index hospitalization had higher readmission rates than those with LOS of 1 day (Citation23). Other studies also suggested longer LOS (≥4 or 5 days) at initial admission was a significant risk factor for asthma rehospitalization (Citation25,Citation40,Citation41).

Ozone level in patients’ neighborhoods also demonstrated a significant association with a higher number of asthma admissions, in both the single-pollutant and two-pollutant models. Our finding is consistent with prior research associating an increased risk of hospital readmission for pediatric asthma with both indoor air pollution (such as bedroom air quality and tobacco exposure) and traffic-related outdoor air pollution (Citation15,Citation42,Citation43). Our result is also consistent with evidence that ozone concentration had a significantly positive association with asthma exacerbations for children (Citation44,Citation45). This study allows us to conclude that outdoor air pollution (ozone) in neighborhoods where children live and play should be considered a significant risk factor for hospitalization among children with asthma.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, since ambient air pollution data collected from the CDC is the estimate of the modeled predictions for two air pollutants, it may not reflect the accurate outdoor air condition, which thereby raises the possibility of measurement error. Second, we used the hospitalization records specific to a single hospital and could not track the patients’ potential admissions to other hospitals. Thus, the number of asthma hospitalizations may be under-counted for some pediatric patients, though this is mitigated by the large hospital size and relatively few other pediatric facilities in the catchment area. Also, since only a single children’s hospital in South Texas was included in this study, we may not generalize the results to other settings. Third, some individual and environmental factors, such as severity of asthma, comorbidities, and tobacco exposure (Citation7,Citation37,Citation42), all of which may affect the risk of asthma rehospitalization, were not available in the hospitalization data. Future studies should consider including these factors to help better understand the characteristics of high hospital utilization for pediatric asthma. Finally, we included all hospitalizations of pediatric patients despite the differences of time interval for each patient. This serves as a limitation given the large time variation between admissions among the patients. Future studies should consider categorizing different time intervals of readmission to examine how risk factors may differ by time interval.

Implications for healthcare system

Our findings have important implications regarding repeated asthma admissions and the opportunity to improve transitional care for patients experiencing higher numbers of hospitalizations. This study emphasizes the need to target strategies for high hospital utilizers. We suggest that hospitals conduct follow-up for at least six months after discharge based on the average times between admission for all readmitted patients (274 days) and the high utilization group (169 days) observed in this study. Several studies also reported that a time interval of six months to two years could be a reasonable criterion for follow up for patients with chronic conditions (Citation26,Citation29,Citation46).

Effective transition of care from hospital to community, including continual follow-up for patients who have a higher risk for readmission, is also important given recent research supporting the significance of transitional care, including asthma education and communication with primary care physicians (PCPs), to reduce readmissions for pediatric asthma (Citation47,Citation48). Therefore, collaboration between clinical and community partners (e.g. PCPs, nonprofit organizations, and educators) for transitional care and follow-up would contribute to reducing repeated hospital admissions since appropriate care for asthma management in the community, such as asthma education, can prevent repeated hospitalizations (Citation49–51).

Conclusions

This study found that a modest number of patients with the highest number of hospitalizations accounted for substantial hospital resource utilization. Our results revealed that young children, longer LOS, warm season at index admission, and high level of outdoor air pollution in residential neighborhoods are associated with a higher number of hospitalizations among children with asthma in South Texas. The findings of this study underscore the importance of effective monitoring of high hospital utilizers and establishing strategies for such patients based on their individual and contextual characteristics to reduce repeated hospitalizations and increase efficiency and optimal use of hospital resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Erin Richmond (program manager) and Jennifer Phillips (data analyst), from Driscoll Children's Hospital, and Scott Horel (data manager), from Texas A&M University School of Public Health, who helped with extracting and converting the data. We also would like to thank Jacob M. Kolman, the Senior Scientific Writer of the Houston Methodist Research Institute Center for Outcomes Research, for his review and editorial support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Global Institute for Hispanic Health.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Carrns A. Farewell, and don’t come back. Health reform gives hospitals a big incentive to send patients home for good. US News World Rep. 2010;147(20):22–23.

- Coye MJ. CMS’ stealth health reform. Plan to reduce readmissions and boost the continuum of care. Hosp Health Netw. 2008;82(24)

- Texas External Quality Review Organization. Potentially preventable readmissions in Texas Medicaid and CHIP programs. The Institute for Child Health Policy; 2014 Dec 02. Available from: https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/about-hhs/process-improvement/medicaid-chip-qei/PPR-FY2013.pdf [last accessed 17 June 2020].

- Chen Y, Dales R, Stewart P, Johansen H, Scott G, Taylor G. Hospital readmissions for asthma in children and young adults in Canada. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36(1):22–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.10307.

- McCaul KA, Wakefield MA, Roder DM, Ruffin RE, Heard AR, Alpers JH, Staugas RE. Trends in hospital readmission for asthma: has the Australian National Asthma Campaign had an effect? Med J Aust. 2000;172(2):62–66.

- Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, Goodman DM, Slonim AD, Sharma V, Shah SS, Pati S, Fargason C, Jr, Hall M. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3395.

- Visitsunthorn N, Lilitwat W, Jirapongsananuruk O, Vichyanond P. Factors affecting readmission for acute asthmatic attacks in children. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2013;31(2):138–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.12932/AP0247.31.2.2013.

- Melnyk BM. Intervention studies involving parents of hospitalized young children: an analysis of the past and future recommendations. J Pediatr Nurs. 2000;15(1):4–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/jpdn.2000.0150004.

- Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, Tang AM, Eastman B, Rawlins LK, Averill RF. Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;30(1):75–91.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: promoting greater efficiency in Medicare. Washington, DC: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC); 2007.

- Regenstein M, Andres E. Reducing hospital readmissions among medicaid patients: a review of the literature. Qual Manag Health Care. 2014;23(4):203–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/QMH.0000000000000043.

- National Priorities Partnership. Preventing Hospital Readmission: A $25 Billion Opportunity. Boston, MA: Network for Excellence in Health Innovation; 2010. Available from: https://www.nehi.net/bendthecurve/sup/documents/Hospital_Readmissions_Brief.pdf [last accessed 19 September 2019].

- Delfino RJ, Chang J, Wu J, Ren C, Tjoa T, Nickerson B, Cooper D, Gillen DL. Repeated hospital encounters for asthma in children and exposure to traffic-related air pollution near the home. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102(2):138–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60244-X.

- Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, Liu X. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001-2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;94:1–8.

- Newman NC, Ryan PH, Huang B, Beck AF, Sauers HS, Kahn RS. Traffic-related air pollution and asthma hospital readmission in children: a longitudinal cohort study. J Pediatr. 2014;164(6):1396–1402.e1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.02.017.

- Chang J, Delfino RJ, Gillen D, Tjoa T, Nickerson B, Cooper D. Repeated respiratory hospital encounters among children with asthma and residential proximity to traffic. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66(2):90–98. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2008.039412.

- Brown MS, Sarnat SE, DeMuth KA, Brown LAS, Whitlock DR, Brown SW, Tolbert PE, Fitzpatrick AM. Residential proximity to a major roadway is associated with features of asthma control in children. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37044. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037044.

- Largent J, Nickerson B, Cooper D, Delfino RJ. Paediatric asthma hospital utilization varies by demographic factors and area socio-economic status. Public Health. 2012;126(11):928–936. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.04.011.

- Conway R, Galvin S, Coveney S, O'Riordan D, Silke B. Deprivation as an outcome determinant in emergency medical admissions. QJM. 2013;106(3):245–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcs233.

- Nkoy FL, Stone BL, Knighton AJ, Fassl BA, Johnson JM, Maloney CG, Savitz LA. Neighborhood deprivation and childhood asthma outcomes, accounting for insurance coverage. Hosp Pediatr. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0032.

- Cournane S, Byrne D, Conway R, O'Riordan D, Coveney S, Silke B. Social deprivation and hospital admission rates, length of stay and readmissions in emergency medical admissions. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(10):766–771. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.09.019.

- Beck AF, Simmons JM, Huang B, Kahn RS. Geomedicine: area-based socioeconomic measures for assessing risk of hospital reutilization among children admitted for asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):2308–2314. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300806.

- Liu SY, Pearlman DN. Hospital readmissions for childhood asthma: the role of individual and neighborhood factors. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(1):65–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490912400110.

- O'Lenick CR, Winquist A, Mulholland JA, Friberg MD, Chang HH, Kramer MR, Darrow LA, Sarnat SE . Assessment of neighbourhood-level socioeconomic status as a modifier of air pollution-asthma associations among children in Atlanta. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(2):129–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206530.

- Chabra A, Chávez GF, Adams EJ, Taylor D. Characteristics of children having multiple Medicaid-paid asthma hospitalizations. Matern Child Health J. 1998;2(4):223–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022307423236.

- Bloomberg GR, Trinkaus KM, Fisher EB, Jr, Musick JR, Strunk RC. Hospital readmissions for childhood asthma: a 10-year metropolitan study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(8):1068–1076. doi:https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2201015.

- Minkovitz CS, Andrews JS, Serwint JR. Rehospitalization of children with asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(7):727–730. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.7.727.

- Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, Hall M, Kueser J, Kaplan W, Neff J. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.122.

- Wallace JC, Denk CE, Kruse LK. Pediatric hospitalizations for asthma: use of a linked file to separate person-level risk and readmission. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(2):A07.

- Sulman J, Savage D, Way S. Retooling social work practice for high volume, short stay. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;34(3–4):315–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/j010v34n03_05.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network. 2018. Available from: www.cdc.gov/ephtracking [last accessed 01 August 2019].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outdoor Air. 2019. Available from: https://ephtracking.cdc.gov/showAirMonModData [last accessed 01 August 2019].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program. CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index 2016 Database Texas. 2016. Available from: https://svi.cdc.gov/data-and-tools-download.html [last accessed 01 Aug 2019].

- Hallisey EJ. Measuring community vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index. J Environ Health. 2018;80:34–36.

- Brewer M, Kimbro RT, Denney JT, Osiecki KM, Moffett B, Lopez K. Does neighborhood social and environmental context impact race/ethnic disparities in childhood asthma? Health Place. 2017;44:86–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.01.006.

- Stanford RH, White J. Cost of asthma in the emergency department and hospital – an analysis of hospital data. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(suppl. 5):A47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2010.09.019.

- Kenyon CC, Melvin PR, Chiang VW, Elliott MN, Schuster MA, Berry JG. Rehospitalization for childhood asthma: timing, variation, and opportunities for intervention. J Pediatr. 2014;164(2):300–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.003.

- Kocevar VS, Bisgaard H, Jönsson L, Valovirta E, Kristensen F, Yin DD, Thomas J. 3rd. Variations in pediatric asthma hospitalization rates and costs between and within Nordic countries. Chest. 2004;125(5):1680–1684. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.5.1680.

- Knighton AJ, Flood A, Speedie SM, Harmon B, Smith P, Crosby C, Payne NR. Does initial length of stay impact 30-day readmission risk in pediatric asthma patients? J Asthma. 2013;50(8):821–827. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2013.816726.

- Veeranki SP, Ohabughiro MU, Moran J, Mehta HB, Ameredes BT, Kuo Y-F, Calhoun WJ. National estimates of 30-day readmissions among children hospitalized for asthma in the United States. J Asthma. 2018;55(7):695–704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1365888.

- Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Even-Shoshan O, Shabbout M, Zhang X, Bradlow ET, Marsh RR. Length of stay, conditional length of stay, and prolonged stay in pediatric asthma. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):867–886. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.00150.

- Howrylak JA, Spanier AJ, Huang B, Peake RWA, Kellogg MD, Sauers H, Kahn RS. Cotinine in children admitted for asthma and readmission. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):e355–e362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2422.

- Vicendese D, Dharmage SC, Tang MLK, Olenko A, Allen KJ, Abramson MJ, Erbas B. Bedroom air quality and vacuuming frequency are associated with repeat child asthma hospital admissions. J Asthma. 2015;52(7):727–731. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.1001904.

- Zhang Y, Ni H, Bai L, Cheng Q, Zhang H, Wang S, Xie M, Zhao D, Su H. The short-term association between air pollution and childhood asthma hospital admissions in urban areas of Hefei City in China: a time-series study. Environ Res. 2019;169:510–516. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.11.043.

- Gharibi H, Entwistle MR, Ha S, Gonzalez M, Brown P, Schweizer D, Cisneros R. Ozone pollution and asthma emergency department visits in the Central Valley, California, USA, during June to September of 2015: a time-stratified case-crossover analysis. J Asthma. 2019;56(10):1037–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2018.1523930.

- Ash M, Brandt S. Disparities in asthma hospitalization in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):358–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.050203.

- Krupp NL, Fiscus C, Webb R, Webber EC, Stanley T, Pettit R, Davis A, Hollingsworth J, Bagley D, McCaskey M, et al. Multifaceted quality improvement initiative to decrease pediatric asthma readmissions. J Asthma. 2017;54(9):911–918. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1281294.

- Parikh K, Hall M, Kenyon C, Teuful R, Mussman G, Montalbano A, Gold J, Antoon JW, Subramony A, Mittal V. Impact of asthma-specific discharge practices on readmission rates for children hospitalized with asthma. Pediatrics. 2018;142:549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.142.1_MeetingAbstract.549.

- Fisher EB, Strunk RC, Highstein GR, Kelley-Sykes R, Tarr KL, Trinkaus K, Musick J. A randomized controlled evaluation of the effect of community health workers on hospitalization for asthma: the asthma coach. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(3):225–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.577.

- Woods ER, Bhaumik U, Sommer SJ, Ziniel SI, Kessler AJ, Chan E, Wilkinson RB, Sesma MN, Burack AB, Klements EM, et al. Community asthma initiative: evaluation of a quality improvement program for comprehensive asthma care. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):465–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3472.

- Kash BA, Baek J, Cheon O, Coleman NE, Jones SL. Successful hospital readmission reduction initiatives: top five strategies to consider implementing today. JHA. 2018;7(5):16–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.5430/jha.v7n6p16.