Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the impact of an intensive pharmaceutical care campaign targeting inappropriate use of triptans. Design. Randomized controlled trial. Setting. 22 community pharmacies in the County of Funen, Denmark. Subjects. A total of 1123 triptan users at intervention pharmacies and 1340 at control pharmacies. Intervention. Intervention pharmacy staff received information on migraine and other types of headache, detection of inappropriate triptan use and other drug-related problems, and techniques for establishing a dialogue with patients. Intervention consisted of a folder and a structured dialogue with the pharmacy staff. The folder included questions aimed at detecting overuse and inappropriate triptan use. Main outcome measures. Change in average triptan consumption in doses per month measured by means of a prescription database with information on all purchases of reimbursed drugs at the level of the individual patient. Results. Overall, intervention had no statistically significant short-term impact on patients’ consumption of triptans either among incident users (intervention/control ratio 1.02; 95% confidence interval 0.95 to 1.12), or among prevalent users (1.02; 0.97 to 1.08). No effects were observed after 6 and 9 months, apart from a possible borderline effect after 9 months among prevalent users with intermediate triptan consumption (0.93; 0.87 to 1.00). Conclusion. The pharmaceutical care campaign did not reduce the use of triptans.

In recent years, Danish community pharmacies have been focusing on improving drug use Citation[1]. One popular method is the “pharmaceutical care” concept, which includes identifying, solving, and preventing drug-related problems Citation[1–4]. The trend towards greater involvement of community pharmacies in the promotion of rational pharmacotherapy has so far largely escaped evaluation in randomized controlled studies, which has given rise to calls for more studies with strong research designs Citation[5], Citation[6]. Most studies have focused on improving compliance among patients using drugs on a daily basis, e.g. diabetics Citation[7], asthmatics Citation[2], Citation[8], elderly patients Citation[3], Citation[9], Citation[10], and patients with hypertension Citation[11]. To our knowledge, no randomized controlled studies have been published on pharmacy-based interventions targeting inappropriate triptan use.

A large proportion of triptan consumption can be attributed to inappropriate use Citation[12], Citation[13]. This includes daily or almost daily use, taking triptans repeatedly for the same headache attack even if the first dose has no effect, and using triptans for tension headache and other conditions where no beneficial effects have been demonstrated. The disadvantages of inappropriate triptan use include medication-induced headache, other adverse effects, and costs Citation[12], Citation[14].

Community pharmacies are increasingly involved in the promotion of rational pharmacotherapy, and their interventions are often designed according to the pharmaceutical care concept.

Until now, no randomized controlled studies have been published on the impact of inappropriate triptan use.

This randomized controlled trial showed no statistically significant impact on the use of triptans and further development and evaluation of the concept of promoting rational pharmacotherapy at community pharmacies is needed.

This study aimed at evaluating the impact of a pharmaceutical care campaign targeting inappropriate use of triptans.

Material and methods

Design

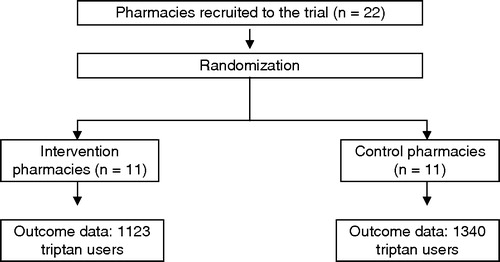

We conducted a randomized controlled study comprising all patients purchasing triptans at community pharmacies in the County of Funen, Denmark (472,000 inhabitants) from September to November 2000. Half of the pharmacies were randomly assigned as intervention pharmacies and the other half as control pharmacies. Only persons attending an intervention pharmacy were informed about the trial. The effect on triptan consumption was evaluated by means of a prescription database with information on all reimbursed drugs at the level of the individual user.

Intervention

We invited all 25 pharmacies in the county to participate and 22 accepted (). Those responsible for providing the intervention at each pharmacy were pharmacists. However, they were encouraged to involve the pharmacy assistants. Further, they were encouraged to assure that all staff at each pharmacy was properly instructed. Intervention pharmacy staff attended a one-day course on migraine and other types of headache, and inappropriate use of triptans and other drug-related problems, and on how to establish a dialogue with patients. The instructors were pharmacists, a general practitioner, a neurologist, and clinical pharmacologists. A manual given to pharmacy staff described how to identify inappropriate triptan use, how to establish a dialogue and how to ask questions. Moreover, it offered suggestions for relevant questions, advice, literature on headache, migraine and pharmaceutical care, and included a checklist. The training package was developed in cooperation with the Danish College of Pharmacy Practice (Pharmakon), which for the past decade has been developing the concept of pharmaceutical care Citation[2]. In order to practise the intervention, all participants took part in role-plays supervised by the instructors. To ensure that the information given was understood, the participants were encouraged to ask questions, and moreover the written course material included a self-test exam.

When presenting a triptan prescription at the pharmacy, the user received a folder designed to support the dialogue and assist the pharmacist in detecting triptan overuse. It included information on the campaign and questions on the patient's drug use, e.g. the type of headache for which the patient used triptans, monthly consumption of triptans, repeated use of triptans even if the first dose had no effect on the attack, and the frequency of use of other types of painkillers. The folder was piloted in another Danish county (the County of Fredensborg).

The dialogue between the pharmacist and the patient took place immediately after the folder had been read and its questions answered. The goal was to identify and reduce the patient's overuse of triptans, e.g. taking triptans for tension-type or drug-induced headache or as a preventive measure against migraine attacks, and taking triptans repeatedly for the same migraine attack if the first dose had had no effect. To ensure an undisturbed, confidential conversation, the pharmacies were encouraged to let the dialogue with triptan users take place in a separate room. If major problems were identified, e.g. if the pharmacist suspected that a patient did not suffer from migraine or cluster headache, and the use of triptans was therefore not indicated, the patient was advised to contact the prescribing physician. The patients were also told about correct triptan use, mode of action, adverse effects, differences between migraine and other types of headache, and factors that can trigger migraine and other types of headache attacks. Each dialogue was estimated to last on average 15 minutes and each triptan user participated only once.

The pharmacies received a fee as compensation for their efforts. The identity of triptan users was not recorded at the pharmacy. In order to assure that the intervention proceeded as planned, the author group regularly contacted all the pharmacies by phone and mail.

Data sources

Data were retrieved from the Odense University Pharmaco-Epidemiologic Database (OPED) Citation[15]. All residents in Denmark are registered by a central personal registration number (CPR number) and pharmacies provide information on all sales of subsidized drugs to the Danish National Health Service and the OPED. We identified patients through their prescriptions using recorded information on CPR number, date of purchase, ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) Code Citation[16], quantity of the drug, and a code identifying the dispensing pharmacy. The Danish Data Protection Agency and the Regional Ethics Committee had approved the study. All GPs in the county were informed about the study.

Outcomes and analysis

We included all triptans available on the Danish market during the intervention period (sumatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, rizatriptan, and almotriptan). Consumption was calculated as the number of doses (tablets, suppositories, injections), regardless of strength.

Patients were assigned to the intervention or the control group depending on which pharmacy they visited on the date of their first triptan purchase during the 3-month intervention period (the index date). We excluded patients who purchased triptans at both intervention and control pharmacies. We evaluated the impact of the information campaign by assessing changes in each patient's average consumption of triptans (doses per month) before and after the index date. We analysed symmetrical 3-, 6-, and 9-month periods in order to detect both short- and long-term effects.

The change in triptan consumption was estimated by means of regression analysis. The distribution of consumption was skewed, but approximated a normal distribution after log transformation. We therefore used linear regression with log average consumption as the dependent variable Citation[17]. The exponentiated coefficient in the regression model can be interpreted as a ratio between the geometric means of consumption in the intervention and the control group. The desired effect is an intervention/control ratio < 1.

We separately analysed incident patients defined as those with no prescriptions during the 3, 6, and 9 months preceding the intervention. For prevalent users, we adjusted for baseline consumption using this variable as a covariate in the regression Citation[18], Citation[19]. We also performed subgroup analyses for users with low (less than 6 doses per month), intermediate (from 6 to 14 doses per month) and high (15 or more doses per month) pre-intervention consumption. All analyses were adjusted for clustering at the pharmacy level because randomization was performed at pharmacy and not at patient level and because we expected variation in patient management to be partly explained by variation between pharmacies Citation[19]. We regarded p < 0.05 as statistically significant. Data were analysed using the programme package Stata version 8.2 Citation[20].

Using prescription data obtained prior to the study (1996–98), we estimated that about 1400 triptan users would be in contact with pharmacies during a 3-month period. Approximately 30% would have intermediate to high consumption exceeding 6 doses per month. A simulation, randomly allocating patients to intervention and control groups, indicated that the study would be able to detect an average reduction of 1 dose per month for the group of intermediate to high consumers.

Results

During the intervention period, a total of 2463 persons purchased triptans: 1123 persons at intervention and 1340 at control pharmacies. A total of 224 persons attending both intervention and control pharmacies were not included. shows that the intervention and the control group were comparable with respect to age, sex distribution, and triptan consumption pattern.

Table I. Characteristics of triptan users in intervention and control groups: Number (percentage of total users within each group) unless otherwise stated.

The campaign had no statistically significant impact on the patients’ consumption of triptans. shows the triptan consumption before and after the intervention. There were no statistically significant effects of the intervention in the short (3 month), intermediate (6 month), or long term (9 month) in any group of triptan users, apart from a possible borderline effect after 9 months for the group with intermediate triptan consumption.

Table II. Geometric means of patients’ triptan consumption (doses per month) for 3-, 6-, and 9-month periods before and after visiting an intervention or control pharmacy: Effect of intervention expressed as an intervention/control ratio (desired effect: less consumption in intervention group, ratio < 1),1 divided by incident and prevalent users and stratified by baseline consumption (95% CI adjusted for clustering at pharmacy level).

Discussion

This study was based on the hypothesis that a pharmaceutical care campaign could reduce inappropriate triptan use. However, our study shows that this does not seem to be the case. Particularly interesting is that we did not find reduced consumption among high users (15 or more doses per month). Only a marginal effect in the intermediate group (more than 6 and less than 15 doses per month) was found.

These results should be considered in the light of the statistical precision of the estimates, the data-collection method, the outcome measures, and a possible ceiling effect. The confidence intervals of the intervention/control ratios allowed us to detect small effects of the intervention corresponding to a 9% reduction in median consumption in the low and intermediate use group and an 18% reduction in the high use group. We were able to calculate each person's purchase of triptans precisely because we had access to complete and detailed information on the drug consumption of all inhabitants in a well-defined area where all prescriptions were electronically recorded and the pharmacists had an economic incentive to provide accurate data Citation[15]. By using these data we also avoided bias commonly affecting patient self-reported data.

We do not exclude the possibility that the information influenced the triptan users in ways not captured by the outcome measures. In theory, patients can use triptans more rationally without changing the amount of triptans bought, but this is hardly likely to be the case. There was also room for reduction of the triptan consumption. We may a priori expect a higher level of inappropriate consumption among those with high average consumption, but the phenomenon is also frequent among patients with more moderate triptan use. A questionnaire survey including 149 triptan users showed that 75% occasionally take triptans repeatedly for the same headache even if the first dose did not have any effect (unpublished results). Migraine sufferers often also suffer from tension-type headache, which is difficult for them to distinguish from migraine and which may therefore lead to inappropriate triptan use Citation[12], Citation[21]. Even moderately frequent use of triptans may cause medication overuse headache for which the only effective therapy is temporary discontinuation Citation[14]. Finally, some patients use triptans for migraine prophylaxis Citation[13]. Reduction of triptan consumption is therefore frequently likely to be indicated even among those whose consumption is low.

may be seen to portray an overall increase in triptan consumption among intervention as well as control group patients. This pattern, however, emerges due to our way of including patients and due to the design: All patients purchased triptans on the index date, and this quantity was included in the calculation of the average consumption after this date, reflecting an apparent increase in consumption. The analysis stratified by baseline consumption is furthermore affected by regression towards the mean. These effects are expected to be identical in the control and the intervention group and therefore do not produce any bias in our results.

We aimed to test the effects of a “real life” pharmaceutical care campaign (effectiveness), and not to evaluate what would happen under ideal circumstances in a group of patients where intervention fully satisfied intentions (efficacy). Typically, healthcare interventions are tested in efficacy studies under ideal circumstances with participation of a subset of particularly interested investigators and under close monitoring in order to ensure that the intervention is carried out exactly as intended. However, interventions that have proved successful in ideal research settings may not work in the real world. Therefore, we aimed to undertake an effectiveness study. A consequence of this deliberate choice could be that our intervention was weaker than under ideal circumstances. Some patients may have refused to participate in the dialogue, and in some cases the intervention may have been insufficient because of lack of time or pharmacy staff commitment. We followed up regularly by phone and personal visits in order to keep the pharmacy staff motivated and this indicated that the campaign in general proceeded as planned, but more intensive monitoring of the pharmacies’ activities would have compromised our intention to study effectiveness. Subsequent patient interviews and questionnaires indicate that even if patients participated as intended, the majority were not prepared to consider a change in their use of triptans (unpublished results).

Only a few large-scale randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effectiveness of community pharmacy-based interventions on drug use. In these studies the effects on drug consumption varied from nil to substantial Citation[5], Citation[22]. A multi-centre, randomized controlled study on an extensive pharmaceutical care programme targeting elderly patients showed some effect on satisfaction and symptom control, but only a minor impact on drug therapy, drug knowledge, and drug compliance Citation[3]. A Cochrane review supports the expanding role of the pharmacist in patient education, but doubts the generalizability of the studies included and the interventions were poorly defined, lacked cost assessments and specification of patient outcome data, and research designs were not sufficiently rigorous Citation[5].

The implications of the disappointing results of our intervention are not that the “pharmaceutical care” concept or the pharmaceutical care provided by community pharmacies should be abandoned. Rather, there is a need to develop and evaluate this concept. Changing patients’ drug use is extremely difficult as it is the result of many factors, including physicians’ inappropriate prescribing practices, which are equally difficult to change Citation[23], Citation[24]. The next step should be to develop and evaluate multidisciplinary interventions involving all the links in the chain of drug use: physicians, pharmacies, and patients.

In conclusion, this pharmaceutical care campaign did not appear to reduce inappropriate use of triptans.

The authors would like to thank the pharmacies for their participation in the trial. The study was supported by The Danish Pharmacy Foundation (Apotekerfonden).

References

- Engelsborg H, Fonnesbaek L, Herborg H, Søndergaard B. Pharmaceutical care over the counter [Farmaceutisk omsorg i skranken]. Pharmakon, Hillerød 1999

- Herborg H, Soendergaard B, Froekjaer B, Fonnesbaek L, Jorgensen T, Hepler C, Grainger-Rousseau TJ, Ersboell BK. Improving drug therapy for patients with asthma, Part 1: Patient outcomes. J Am Pharm Assoc 2001; 41: 539–50

- Bernsten C, Björkman I, Caramona M, Crealey G, Frokjær B, Grundberger E, Gustafsson T, Henman M, Herborg H, Hughes C, McElnay J, Magner M, Van Mil F, Schaeffer M, Silva, Søndergaard B, Sturgess I, Tromp D, Vivero L, Winterstein A. Improving the well-being of elderly patients via community pharmacy-based provision of pharmaceutical care: A multicentre study in seven European countries. Drugs and Aging 2001; 18: 63–77

- Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990; 47: 533–43

- Beney, J, Bero, LA, Bond, C. Expanding the roles of outpatient pharmacists: Effects on health services utilisation, costs, and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; CD000336.

- Lipton HL, Byrns PJ, Soumerai SB, Chrischilles EA. Pharmacists as agents of change for rational drug therapy. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1995; 11: 485–508

- Veldhuizen-Scott MK, Widmer LB, Stacey SA, Popovich NG. Developing and implementing a pharmaceutical care model in an ambulatory care setting for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Educ 1995; 21: 117–23

- Grainger-Rousseau TJ, McElnay JC. A model for community pharmacist involvement with general practitioners in the management of asthma patients. J Applied Therapeutics 1996; 1: 143–61

- Vinicor F. Diabeds: A randomized trial of the effects of physician and/or patient education on diabetes patient outcomes. J Chron Dis 1987; 40: 345–56

- Kassam R, Farris KB, Burback L, Volume CI, Cox CE, Cave A. Pharmaceutical care research and education project: Pharmacists’ interventions. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2001; 41: 401–10

- Carter BL, Barnette DJ, Chrischilles E, Mazzotti GJ, Asali ZJ. Evaluation of hypertensive patients after care provided by community pharmacists in a rural setting. Pharmacotherapy 1997; 17: 1274–85

- Gaist D. Use and overuse of sumatriptan: Pharmacoepidemiological studies based on prescription register and interview data. Cephalalgia 1999; 19: 735–61

- Gaist D, Tsiropoulos I, Sindrup SH, Hallas J, Rasmussen BK, Kragstrup J, Gram LF. Inappropriate use of sumatriptan: Population based register and interview study. BMJ 1998; 316: 1352–3

- Limmroth V, Katsarava Z, Fritsche G, Przywara S, Diener HC. Features of medication overuse headache following overuse of different acute headache drugs. Neurology 2002; 59: 1011–14

- Gaist D, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish Prescription registries. Dan Med Bull 1997; 44: 445–8

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: ATC index with DDDs. Oslo: WHO; 2004.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. The use of transformation when comparing two means. BMJ 1996; 312: 1153

- Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ 2001; 323: 1123–4

- Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Arnold, London 2000

- Stata Corp. 2004, Release 8.2. Stata Statistical Software, release 8.2. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2004.

- Williams D, Cahill T, Dowson A, Fearon H, Lipscombe S, O'Sullivan E, Rees T, Strang C, Valori A, Watson D. Usage of triptans among migraine patients: An audit in nine GP practices. Curr Med Res Opin 2002; 18: 1–9

- Haynes, RB, Montague, P, Oliver, T, McKibbon, KA, Brouwers, MC, Kanani, R. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000; CD000011.

- Bjerrum L, Andersen M, Petersen G, Kragstrup J. Exposure to potential drug interactions in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 153–8

- Søndergaard J, Andersen M, Støvring H, Kragstrup J. Mailed prescriber feedback to a clinical guideline has no impact: A randomised, controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care 2003; 21: 47–51